Abstract

We study the crossed Andreev reflection and the nonlocal transport in the staggered graphene/superconductor/periodic line defect superlattice (LDGSL) junctions. The staggered pseudospin potential in the left graphene electrode suppress the local Andreev reflection, while the elastic cotunneling of K′ valley electrons is inhibited due to the exclusive rightward motion of K valley electrons in the right LDGSL electrode, thereby enabling the realization of dominant intravalley crossed Andreev reflection for incident electrons from the K′ valley. Meanwhile, the intravalley elastic cotunneling occurs while both local Andreev reflection and crossed Andreev reflection are completely eliminated for incident electrons in the K valley. Furthermore, the probability of intervalley crossed Andreev reflection scattering is significantly lower than that of intravalley CAR scattering across a broad range of incident angles and electron energies. Our results are helpful for designing the flexible and high-efficiency Cooper pair splitter based on the valley degree of freedom.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum entanglement among microscopic particles has garnered significant attention due to its intrinsic importance and prospective applications in quantum information technologies1. Superconductors are considered natural sources of entangled electrons, as Cooper pairs consist of two electrons with interdependent spin and momentum characteristics2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Through the process of Cooper pair splitting, spatially separated spin-entangled electrons can be generated at the junction of a conductor and a superconductor. This mechanism’s time-reversed counterpart is known as crossed Andreev reflection (CAR) or non-local Andreev reflection. CAR represents a nonlocal process that converts an incoming electron from a voltage-biased lead into an outgoing hole in a spatially separated grounded lead via Cooper pair formation within the grounded superconductor10,11. The efficiency of CAR serves as a direct indicator of the effectiveness of Cooper pair splitting.

The realization of the CAR has garnered significant attention in both theoretical and experimental researchers12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. However, the emergence of CAR is generally accompanied by competing processes such as local Andreev reflection (LAR), normal reflection (NR), and elastic cotunneling (ECT). The LAR process converts an incoming electron from one electrode into a hole within the same electrode via Andreev reflection. In contrast, NR occurs when an electron is simply reflected at the interface without Andreev conversion, while ECT refers to the coherent transfer of an electron from one electrode to the other without forming a Cooper pair. These competing processes can obscure the detection of CAR, leading to a complete cancellation of the conductivities associated with ECT and CAR. This necessitates the use of noise measurements to identify the distinct signature of the CAR process in superconducting heterostructures.

Recent advancements have proposed methods to enhance CAR signals by mitigating both ECT and LAR processes through various types of leads, including normal metals, ferromagnetic metals, antiferromagnetic metals, and topological insulators26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. For instance, perfect CAR has been achieved in hybrid junctions formed by n-type and p-type semiconductors through band-structure-induced energy filtering6. Specialized circuits utilizing helical edge states of topological insulators have been designed to achieve perfect CAR27. Additionally, a mechanism for achieving perfect CAR has been theoretically proposed in superconductors situated between two antiferromagnetic layers, with one being electron-doped and the other hole-doped32.

Furthermore, CAR can be realized in graphene/superconductor/graphene junctions by exploiting the valley degree of freedom35,36,37,38,39,40. Initial investigations into graphene-based devices aimed to achieve perfect CAR primarily focused on the zero density of states at the Dirac point35. In a zigzag graphene nanoribbon/superconductor/nanoribbon junction, exclusive CAR can be attained with complete suppression of both ECT and LAR, attributable to the valley selection rule in even zigzag nanoribbons37. The introduction of a staggered pseudo-spin potential and intrinsic spin-orbit coupling within graphene enables perfect CAR for electrons with a designated spin-valley index40.

In this study, we propose a distinct mechanism to achieve valley-dependent dominant CAR in proximitized graphene/ superconductor/ periodic line defect superlattice (LDGSL) junctions. The lattice structure of the LDGSL consists of extended line defects that are periodically embedded along the y-direction, forming a superlattice41. Due to this periodicity, \(k_y\) remains a conserved quantum number. In Fig. 1a, we illustrate one such extended line defect, while in reality, they repeat periodically along y. The heterojunction extends along the x-direction, where electronic transport occurs. The dispersion of the LDGSL for \(k_y = 0\) is shown on the right side of Fig. 1b. Notably, the LDGSL functions as a valley filter by utilizing valley-dependent transmission properties near the bottom conduction band edge, where electrons near the K and K′ points exhibit distinct group velocities. This feature allows the LDGSL to selectively permit rightward propagation for electrons (holes) in the K (K′) valley and leftward propagation for electrons (holes) in the K′ (K+) valley. In our junction configuration, the left graphene electrode features a pseudospin staggered potential induced by the proximity effect of the substrate42,43,44,45,46,47. We first demonstrate that if the left graphene electrode is gapless, LAR diminishes the occurrence of CAR. Upon introducing the staggered pseudospin potential, the left graphene electrode becomes insulating for the hole band, enabling exclusive CAR for K′ electrons while completely suppressing LAR and ECT. Conversely, ECT can manifest for K electrons while both LAR and CAR are suppressed. Moreover, both CAR and ECT processes are predominantly governed by intra-valley scattering. Additionally, we analyze the relationship between scattering probabilities and the incident angle \(\theta\), demonstrating that both inter-valley and intra-valley scattering probabilities rise with increasing \(\theta\), while intra-valley scattering probabilities considerably surpass those of inter-valley scattering. This indicates that dominant CAR with incident K′ valley electrons can be achieved across a wide range of incident angles and energy.

The structure of the remainder of the paper is as follows. Section 2 presents the proposed structure and establishes the theoretical framework for calculating valley-related scattering probabilities as well as local and nonlocal conductances. In Section 3, we provide numerical results regarding intra-valley and inter-valley scattering for the NR, LAR, ECT, and CAR processes, along with the local and nonlocal conductance within the proposed structure. Finally, Section 4 offers a brief summary of the findings.

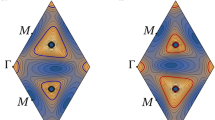

(a) Schematic of the proposed proximitized staggered graphene/superconductor/LDGSL junction. The shaded green area in the right LDGSL region indicates the unit cell of the superlattice, with \(\vec {b}_{1(2)}\) as primitive vectors. \(N\) denotes the transverse dimension of the LDGSL unit cell, while its longitudinal dimension is \(2a\). The junction is translationally symmetric along the \(y\)-axis with periodicity \(\left| \vec {b}_2\right|\). Hopping energies \(\tau _1\) and \(\tau _2\) represent the carbon-carbon bonds around the line defect. A external bias voltage \(V\) is applied to the left graphene electrode, while the superconductor and the right LDGSL are grounded (i.e., their external bias voltage is set to zero), with the chemical potential \(\mu _R\) tunable via gate voltage. (b) Band structure showing the dispersion of electrons (solid black lines) and holes (dashed red lines) in the left proximitized graphene and the right LDGSL for fixed \(k_y = 0\). The expanded unit cell in the left proximitized graphene (shaded green region above) introduces additional subbands. The electron gap in the left proximitized graphene spans from \(-\mu _L - \Delta\) to \(-\mu _L + \Delta\), and the hole gap ranges from \(\mu _L - \Delta\) to \(\mu _L + \Delta\), where \(\Delta\) is the on-site staggered potential and \(\mu _L\) is the chemical potential. Arrows indicate group velocity directions for each state. The solid red circle represents \(K\) electrons, while solid and hollow blue circles denote \(K'\) electrons and holes, respectively. For incident \(K'\) electrons within the hole gap range, LAR is suppressed; these electrons can only tunnel to \(K'\) holes via intra-valley CAR. In contrast, incident \(K\) electrons can tunnel to \(K\) electrons through inter-valley ECT. (c) The original Dirac points \(K\) and \(K'\) at \([\pm 4\pi /3a, 0]\) in pristine graphene are shifted to \({\widehat{K}}\) and \({\widehat{K}}'\) in the superlattice at \([\pm \pi /3a, 0]\).

Theoretical model

In Fig. 1a, we present a schematic representation of the proximitized graphene /superconductor/LDGSL configuration within the \(xy\) plane, with junction interfaces located at \(x=0\) and \(x=L\), where electronic transport is directed along the \(x\)-axis. The staggered potential \(\Delta\) in the left graphene is attributed to the substrate, while the superconducting gap \(\Delta _{0}\) in the central region is induced by a bulk superconductor via the proximity effect. The right section features a one-dimensional LDGSL superlattice, created by periodically embedding extended line defects along the \(y\) direction in pristine graphene. The unit cell size of the LDGSL in the \(x\) direction measures \(2a\) with a being the graphene lattice constant, while the dimension in the \(y\) direction is characterized by the integer \(N\)41. The left pristine graphene sheet is infinitely wide along the \(y\) direction. Due to the distinct lattice vectors of the LDGSL compared to graphene, the original Dirac points \(K\) and \(K'\) at \([\pm 4\pi /3a, 0]\) in pristine graphene shift to the new Dirac points \(\widehat{K}\) and \(\widehat{K'}\) in the superlattice, now located at \([\pm \pi /3a, 0]\), as illustrated in Fig. 1c. The hopping energies \(\tau _{1}\) and \(\tau _{2}\) between nearest-neighbor lattice points on the line defect within the tight-binding model may differ from the uniform nearest-neighbor hopping energy \(t\) of pristine graphene, indicating lattice distortion surrounding the line defect.

The following model Hamiltonian is employed here to describe the system:

where \(H_L\) describes the left proximitized graphene with straggered potential, \(H_S\) denoted a superconducting graphene caused by a bulk superconductor through proximity effect, and \(H_R\) stands for the LDGSL electrode. In the tight-binding representation, the Hamiltonians \(H_L\), \({H_S}\) and \({H_R}\) are defined as follows:

where \(c_i^\dagger\) and \(d_{i,\alpha }^\dagger\) represent the creation operators for an electron at lattice site \(i\) and in sublattice \(\alpha\) of the line defect, respectively. \(\langle ... \rangle\) refer to nearest-neighbor sites. The hopping integral is represented by \(t\), and \(\Delta\) denotes the on-site staggered potential, where \(\xi _{c_i} = 1\) corresponds to sublattice \(A\) and \(\xi _{c_i} = -1\) to sublattice \(B\). \(\Delta _0\) refers to the induced superconducting pairing. Additionally, \(\tau _{1(2)}\) signifies the hopping energy associated with carbon-carbon bonds surrounding the line defect, and \(\mu _{L(S,R)}\) represents the Fermi level, which can be modulated through gate voltage technology. Note that the line defect atoms and the surrounding graphene atoms in the right electrode share the same chemical potential \(\mu _R\), as they are part of the same electronic system.

The valley-dependent transmission coefficients are determined utilizing the S-matrix method, a widely recognized approach in the field of mesoscopic physics48. In this investigation, we numerically implement the S-matrix method through KWANT49, a Python library specifically designed for calculating the S-matrix of scattering regions within tight-binding frameworks. The model previously defined is compatible with the KWANT methodology for S-matrix computations. The scattering matrix \(\tau\) yields the scattering amplitude \(\tau _{{k_1}{k_2}, \alpha \beta }^{ij}\), which describes the transmission from the incoming \(k_2\) state of particle type \(\beta\) in lead \(j\) to the outgoing \(k_1\) state of particle type \(\alpha\) in lead \(i\)50. Subsequently, the valley-dependent transmission coefficients can be derived using the following formula:

where \(T_{{K_1}{K_{2,}}ee}^{LL}\) and \(T_{{K_1}{K_{2,}}he}^{LL}\) denote the valley-dependent NR and LAR processes, respectively, while \(T_{{K_1}{K_{2,}}ee}^{RL}\) and \(T_{{K_1}{K_{2,}}he}^{RL}\) refer to the valley-related ECT and CAR processes. Furthermore, the condition \(\hbox {K}_1\)=\(\hbox {K}_2\) signifies intravalley scattering, whereas \(\hbox {K}_1\ne\) \(\hbox {K}_2\) indicates intervalley scattering.

Based on the Blonder-Tinkham-Klapwijk framework51, the valley-dependent normalized conductance matrix at a bias voltage \(V\) and at zero temperature can be expressed as follows:

where \(N_{{K_1},e}^j\) represents the number of transverse modes associated with the K\(_1\) valley in the left graphene at the transverse wavevector \(k_y\). The terms \(\sigma _{{K_1}}^{ij}\) correspond to the local conductance when \(i=j\) and the nonlocal conductance when \(i \ne j\). Additionally, \(k_y\) serves as a conserved quantum number due to the translational symmetry along the \(y\)-axis. The Fourier transformation is performed using the wraparound function in Kwant.

Numerical results

Plots of the transmission probabilities for intra- and intervalley NR (a), LAR (b), ECT (c), and CAR (d) as functions of the incident electronic energy \(E\) at an incident angle of \(\theta = 0\), specifically for the condition where \(\Delta = 0\). \(T_{K_{1}K_{2}}\) denotes the transmission probability of \(K_2\) valley particles to \(K_1\) valley particles.

In our calculations, we use the superconducting gap \(\Delta _0 = 0.001 \, \textrm{eV}\) as the unit of energy. \(\mu _S\) is taken as \(\mu _S = 20\Delta _0\). Similarly, \(\mu _R\) is also set to \(20\Delta _0\), ensuring that the energy range under consideration remains within the flat lowest conduction band and the corresponding hole band, thereby excluding minor dips near the K and K\('\) points from transport. \(\mu _L\) is designated as \(0.5\Delta _0\). Suppose a variation of less than 5\(\%\) in the hopping terms \(\tau _1\) and \(\tau _2\), and here we adopt \(\tau _1 \approx \tau _2 \approx t = 2.8 \, \textrm{eV}\)52. The length of the superconducting region is set to \(L = 1500a\), while the width of a unit cell of the LDGSL is set to \(N = 32\).

Plots of the transmission probabilities for intra- and intervalley NR (a), LAR (b), ECT (c), and CAR (d) as a function of the incident electronic energy \(E\) at an incident angle of \(\theta = 0\), under the condition where \(\Delta = 0.25 \Delta _0\). \(T_{K_{1}K_{2}}\) denotes the transmission probability of \(K_2\) valley particles to \(K_1\) valley particles. Aside from \(\mu _L = \Delta _0\), all other parameters in the inset of panel (d) are consistent with those in panel (d).

Firstly, we consider the left graphene without the pseudospin staggered potential, i.e., \(\Delta = 0\), resulting in gapless and linear dispersion for both electrons and holes in graphene. Fig. 2 illustrates the intra- and intervalley scattering spectra for NR, LAR, CAR, and ECT processes as a function of incident energy \(E\) at \(k_y = 0\) (i.e., normal incidence with \(\theta = 0\)). For the ECT process, only the intra-valley transmission \(T_{{K}{K},ee}^{RL}\) is significant, while other processes can be disregarded (see Fig. 2c). This phenomenon can be attributed to the valley filtering effect, which originates from the presence of a single rightward-propagating mode in the K valley within the right LDGSL electrode. In the case of LAR, intervalley scattering associated with both the K and K\('\) valleys (\(T_{{K'}{K},he}^{LL}\) and \(T_{{K}{K'},he}^{LL}\)) occurs within the energy range \(0< E < \Delta _0\), as illustrated in Fig. 2b. Notably, \(T_{{K'}{K},he}^{LL}\) is less than \(T_{{K}{K'},he}^{LL}\) due to the ability of K valley electrons to tunnel into the right LDGSL electrode, whereas K\('\) valley electrons can only be normally reflected (see Fig. 2a). In contrast to LAR and ECT, all intra- and intervalley CAR processes can be neglected, as demonstrated in Fig. 2d. Thus, this configuration employs the right LDGSL electrode to block tunneling of K\('\) valley electrons. Additionally, for CAR to take place, it is essential to suppress LAR process occurring in the left electrode.

(a) Intra-valley CAR probabilities for incident \(K'\) electrons, denoted as \(T_{{K'}{K'},he}^{RL}\), in the \((E, \theta )\) space; (b) Inter-valley CAR probabilities for incident \(K\) electrons, represented as \(T_{{K'}{K},he}^{RL}\), in the \((E, \theta )\) space; (c) Intra-valley ECT probabilities for incident \(K\) electrons, denoted as \(T_{{K}{K},ee}^{RL}\), in the \((E, \theta )\) space; (d) Inter-valley ECT probabilities for incident \(K'\) electrons, represented as \(T_{{K}{K'},ee}^{RL}\), in the \((E, \theta )\) space. The parameters are consistent with those presented in Fig. 3.

The LAR process can be effectively suppressed by employing either \(n\)-type or \(p\)-type graphene. This suppression relies on the principle that an electron cannot be reflected as a hole within the same electrode if the hole band is artificially rendered insulating. When a pseudospin staggered potential \(\Delta \ne 0\) is introduced, an energy gap of \(2\Delta\) emerges. This gap for electrons extends from \(-\Delta - \mu _L\) to \(\Delta - \mu _L\), while the corresponding gap for holes spans from \(-\Delta + \mu _L\) to \(\Delta + \mu _L\), as shown in Fig. 1b. Within the energy range defined by the hole band gap, LAR is absent for incident electrons. In Fig. 3, we consider the scattering spectra under a finite pseudospin staggered potential of \(\Delta = 0.25 \Delta _0\), with other parameters consistent with those in Fig. 2. As anticipated, LAR is zero within the energy range \(0.25 \Delta _0< E < 0.75 \Delta _0\) and nonzero outside this interval, as demonstrated in Fig. 3b. Furthermore, nonlocal ECT processes associated with intravalley scattering \(T_{{K'}{K'},ee}^{RL}\) are prohibited, while those related to intervalley scattering \(T_{{K}{K'},ee}^{RL}\) are minimal (refer to Fig. 3c). Consequently, CAR can occur in the injection of K\('\) electrons \(T_{{K'}{K'},he}^{RL}\) without LAR and ECT (shown in Fig. 3d), even outside the superconducting gap, as depicted in the inset of Fig. 3d. In contrast, for incident K electrons within the energy gap of hole gap, both LAR processes (\(T_{{K'}{K},he}^{LL}\) and \(T_{{K}{K},he}^{LL}\)) as well as intra-valley CAR \(T_{{K}{K},he}^{RL}\) are zero, while inter-valley CAR \(T_{{K'}{K},he}^{RL}\) is negligibly small, leaving only a finite intra-valley ECT \(T_{{K}{K},ee}^{RL}\). Thus, by analyzing the carrier type in the right LDGSL electrode, it is possible to ascertain whether the incident electron is a K or K\('\) valley electron. These processes are clearly illustrated in Fig. 1b, offering a visual representation of the mechanisms discussed above. Furthermore, unlike the previous scenario where \(\Delta _{0} = 0\), the intervalley NR processes \(T_{{K'}{K},ee}^{LL}\) and \(T_{{K}{K'},ee}^{LL}\) occur alongside \(T_{{K'}{K'},ee}^{LL}\) from both valleys, as demonstrated in Fig. 3a.

To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the interplay between CAR and ECT as a function of the angle of incidence, we present the inter-valley and intra-valley CAR and ECT probabilities within the \((E, \theta )\) parameter space, as depicted in Fig. 4. When the energy of the incident electron at the left electrode falls within the energy gap of the corresponding hole and the angle of incidence is near \(\theta = 0\), the probabilities for both intra- and inter-valley CAR and ECT exhibit minimal variation, with intra-valley scattering probabilities markedly surpassing those of inter-valley scattering, as illustrated by the comparisons between Fig. 4a–d. This phenomenon suggests that when electrons from the K\('\) valley impinge upon the left electrode, nearly ideal CAR occurs at the right LDGSL electrode, while ECT is observed for electrons originating from the K valley. As the incident angle \(\theta\) increases, the energy ranges favorable for intra-valley CAR and ECT broaden. This behavior is attributed to the critical angle for LAR, defined by \({\theta _c} = \arcsin \sqrt{{{\left| {{{(E - {\mu _L})}^2} - {\Delta ^2}} \right| } \Bigg / {\left( {{{(E + {\mu _L})}^2} - {\Delta ^2}} \right) }}} \mathrm{ }\) , where \(\theta _c\) represents the angular threshold beyond which LAR ceases to occur53. Concurrently, both intra-valley and inter-valley scattering probabilities increase with \(\theta\). The enhancement of inter-valley CAR and ECT scattering can be attributed to the reduced effective separation of the electronic states near the two valleys as \(k_y\) becomes non-zero in the band structure of the right LDGSL electrode with increasing incident angle \(\theta\). The increase in intra-valley scattering with \(\theta\) can be elucidated by the upward shift of the conduction band minimum in the left graphene, which facilitates a more effective alignment of the conduction band slopes between the two electrodes.

Finally, We examine both local and nonlocal conductance as shown in Fig. 5. The local conductance for incoming electrons from the K and K\('\) valleys exhibits a notable reduction as the bias voltage increases from \(V = 0\). Importantly, within the energy interval \(0.25 \Delta _0< E < 0.75 \Delta _0\), where no holes are present, the local conductance does not converge to zero, as typically observed in two-terminal graphene/superconductor junctions; rather, it indicates the contribution of nonlocal processes. Furthermore, the LAR within the energy range \(0< E < 0.25 \Delta _0\) corresponds to retro-Andreev reflection, whereas the LAR within the energy range \(0.75 \Delta _0< E < \Delta _0\) is associated with specular Andreev reflection. Regarding nonlocal conductivity, for incident electrons in the K\('\) valley, the conductivity remains relatively constant within the energy gap, facilitating nearly ideal CAR. However, as the energy of the incident electrons deviates from the energy gap, the CAR decreases towards zero. Conversely, for electrons originating from the K valley, the nonlocal conductivity remains largely stable both inside and outside the energy gap. Within the energy gap, the total conductivity is low due to the cancellation between CAR and ECT, while outside the energy gap, it approaches a value determined primarily by ECT.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this investigation presents an new approach for achieving valley-dependent dominant CAR in straggered graphene/superconductor/LDGSL junctions. By employing a staggered pseudospin potential and the valley-filtering effect of the LDGSL, we effectively suppress LAR and ECT, thereby facilitating exclusive intra-valley CAR. The results indicate that intra-valley CAR scattering is predominantly unaffected by the angle of incidence and is considerably greater than inter-valley CAR scattering. These findings make a important contribution to the understanding of electron transport phenomena in defect-based junctions and highlight the potential for harnessing valley-dependent physics within quantum information technologies.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Vidal, G. Efficient classical simulation of slightly entangled quantum computations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 147902. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.147902 (2003).

Chtchelkatchev, N. M., Blatter, G., Lesovik, G. B. & Martin, T. Bell inequalities and entanglement in solid-state devices. Phys. Rev. B 66, 161320. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.66.161320 (2002).

Sauret, O., Martin, T. & Feinberg, D. Spin-current noise and bell inequalities in a realistic superconductor-quantum dot entangler. Phys. Rev. B 72, 024544. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.72.024544 (2005).

Nilsson, J., Akhmerov, A. R. & Beenakker, C. W. J. Splitting of a cooper pair by a pair of Majorana bound states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 120403. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.120403 (2008).

Hofstetter, L., Csonka, S., Nygård, J. & Schönenberger, C. Cooper pair splitter realized in a two-quantum-dot y-junction. Nature 461, 960–963. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08432 (2009).

Veldhorst, M. & Brinkman, A. Nonlocal cooper pair splitting in a psn junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 107002. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.107002 (2010).

Hofstetter, L. et al. Finite-bias cooper pair splitting. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 136801. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.136801 (2011).

Tan, Z. B. et al. Cooper pair splitting by means of graphene quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 096602. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.096602 (2015).

Pandey, P., Danneau, R. & Beckmann, D. Ballistic graphene cooper pair splitter. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 147701. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.147701 (2021).

Recher, P., Sukhorukov, E. V. & Loss, D. Andreev tunneling, coulomb blockade, and resonant transport of nonlocal spin-entangled electrons. Phys. Rev. B 63, 165314. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.63.165314 (2001).

Zhu, Y., Sun, Q.-F. & Lin, T.-H. Andreev reflection through a quantum dot coupled with two ferromagnets and a superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 65, 024516. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.65.024516 (2001).

Yamashita, T., Takahashi, S. & Maekawa, S. Crossed Andreev reflection in structures consisting of a superconductor with ferromagnetic leads. Phys. Rev. B 68, 174504. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.68.174504 (2003).

Mélin, R. & Peysson, S. Crossed Andreev reflection at ferromagnetic domain walls. Phys. Rev. B 68, 174515. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.68.174515 (2003).

Mélin, R. & Feinberg, D. Sign of the crossed conductances at a ferromagnet/superconductor/ferromagnet double interface. Phys. Rev. B 70, 174509. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.70.174509 (2004).

Beckmann, D., Weber, H. B. & Löhneysen, H. V. Evidence for crossed Andreev reflection in superconductor-ferromagnet hybrid structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 197003. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.197003 (2004).

Benjamin, C. Crossed Andreev reflection as a probe for the pairing symmetry of ferromagnetic superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 74, 180503. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.74.180503 (2006).

Cadden-Zimansky, P. & Chandrasekhar, V. Nonlocal correlations in normal-metal superconducting systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 237003. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.237003 (2006).

Chen, W., Shen, R., Sheng, L., Wang, B. G. & Xing, D. Y. Resonant nonlocal Andreev reflection in a narrow quantum spin hall system. Phys. Rev. B 84, 115420. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.84.115420 (2011).

Liu, J., Song, J., Sun, Q.-F. & Xie, X. C. Even-odd interference effect in a topological superconducting wire. Phys. Rev. B 96, 195307. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.96.195307 (2017).

Reeg, C., Klinovaja, J. & Loss, D. Destructive interference of direct and crossed Andreev pairing in a system of two nanowires coupled via an s -wave superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 96, 081301. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.96.081301 (2017).

Zhang, K., Zeng, J., Dong, X. & Cheng, Q. Spin dependence of crossed Andreev reflection and electron tunneling induced by Majorana fermions. J. Phys. 30, 505302. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648X/aaedf6 (2018).

Liu, Y., Yu, Z.-M., Liu, J., Jiang, H. & Yang, S. A. Transverse shift in crossed Andreev reflection. Phys. Rev. B 98, 195141. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.98.195141 (2018).

Wang, Y.-X., Wang, X. & Li, Y.-X. Double local and double nonlocal Andreev reflections in nodal-line semimetal-superconducting heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 105, 195402. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.105.195402 (2022).

Galambos, T. H., Ronetti, F., Hetényi, B., Loss, D. & Klinovaja, J. Crossed Andreev reflection in spin-polarized chiral edge states due to the Meissner effect. Phys. Rev. B 106, 075410. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.106.075410 (2022).

Gül, Ö. et al. Andreev reflection in the fractional quantum hall state. Phys. Rev. X 12, 021057. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.12.021057 (2022).

Reinthaler, R. W., Recher, P. & Hankiewicz, E. M. Proposal for an all-electrical detection of crossed Andreev reflection in topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 226802. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.226802 (2013).

Wang, J., Hao, L. & Chan, K. S. Quantized crossed-Andreev reflection in spin-valley topological insulators. Phys. Rev. B 91, 085415. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.91.085415 (2015).

Zhang, Y.-T., Hou, Z., Xie, X. C. & Sun, Q.-F. Quantum perfect crossed Andreev reflection in top-gated quantum anomalous hall insulator-superconductor junctions. Phys. Rev. B 95, 245433. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.95.245433 (2017).

Zhou, Y.-F., Hou, Z., Zhang, Y.-T. & Sun, Q.-F. Chiral Majorana fermion modes regulated by a scanning tunneling microscope tip. Phys. Rev. B 97, 115452. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.97.115452 (2018).

Zhang, S.-B. & Trauzettel, B. Perfect crossed Andreev reflection in Dirac hybrid junctions in the quantum hall regime. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 257701. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.257701 (2019).

Li, Q. et al. Multiple Majorana edge modes in magnetic topological insulator-superconductor heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 102, 205402. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.102.205402 (2020).

Jakobsen, M. F., Brataas, A. & Qaiumzadeh, A. Electrically controlled crossed Andreev reflection in two-dimensional antiferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 017701. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.127.017701 (2021).

Lu, W.-T. & Sun, Q.-F. Electrical control of crossed Andreev reflection and spin-valley switch in antiferromagnet/superconductor junctions. Phys. Rev. B 104, 045418. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.104.045418 (2021).

Fuchs, J., Barth, M., Gorini, C., Adagideli, İ & Richter, K. Crossed Andreev reflection in topological insulator nanowire t junctions. Phys. Rev. B 104, 085415. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.104.085415 (2021).

Cayssol, J. Crossed Andreev reflection in a graphene bipolar transistor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 147001. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.147001 (2008).

Benjamin, C. & Pachos, J. K. Detecting entangled states in graphene via crossed Andreev reflection. Phys. Rev. B 78, 235403. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.78.235403 (2008).

Wang, J. & Liu, S. Crossed Andreev reflection in a zigzag graphene nanoribbon-superconductor junction. Phys. Rev. B 85, 035402. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.85.035402 (2012).

Crépin, F., Hettmansperger, H., Recher, P. & Trauzettel, B. Even-odd effects in nsn scattering problems: Application to graphene nanoribbons. Phys. Rev. B 87, 195440. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.87.195440 (2013).

Beconcini, M., Polini, M. & Taddei, F. Nonlocal superconducting correlations in graphene in the quantum hall regime. Phys. Rev. B 97, 201403. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.97.201403 (2018).

Zhao, S.-C., Gao, L., Cheng, Q. & Sun, Q.-F. Perfect crossed Andreev reflection in the proximitized graphene/superconductor/proximitized graphene junctions. Phys. Rev. B 108, 134511. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.108.134511 (2023).

Xiao-Ling, L. et al. Valley polarized electronic transmission through a line defect superlattice of graphene. Phys. Rev. B 86, 045410. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.86.045410 (2012).

Zihlmann, S. et al. Large spin relaxation anisotropy and valley-Zeeman spin-orbit coupling in wse2 /graphene/ h -bn heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 97, 075434. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.97.075434 (2018).

Zollner, K. & Fabian, J. Proximity effects in graphene on monolayers of transition-metal phosphorus trichalcogenides mpx3(m:mn, fe, ni, co, and x: S, se). Phys. Rev. B 106, 035137. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.106.035137 (2022).

Khatibi, Z. & Power, S. R. Proximity spin-orbit coupling in graphene on alloyed transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 106, 125417. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.106.125417 (2022).

Zollner, K., Cummings, A. W., Roche, S. & Fabian, J. Graphene on two-dimensional hexagonal bn, aln, and gan: Electronic, spin-orbit, and spin relaxation properties. Phys. Rev. B 103, 075129. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.103.075129 (2021).

Wakamura, T. et al. Spin-orbit interaction induced in graphene by transition metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B 99, 245402. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.99.245402 (2019).

Frank, T., Gmitra, M. & Fabian, J. Theory of electronic and spin-orbit proximity effects in graphene on cu(111). Phys. Rev. B 93, 155142. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.93.155142 (2016).

Waintal, X. et al. Computational quantum transport. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.16257.

Groth, C. W., Wimmer, M., Akhmerov, A. R. & Waintal, X. Kwant: A software package for quantum transport. New J. Phys. 16, 063065. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/16/6/063065 (2014).

Jana, K. & Muralidharan, B. Robust all-electrical topological valley filtering using monolayer 2d-xenes. npj 2D Mater. Appli. 6, 19. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-022-00291-y (2022).

Blonder, G. E., Tinkham, M. & Klapwijk, T. M. Transition from metallic to tunneling regimes in superconducting microconstrictions: Excess current, charge imbalance, and supercurrent conversion. Phys. Rev. B 25, 4515–4532. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.25.4515 (1982).

Liu, Y., Song, J., Li, Y., Liu, Y. & Sun, Q.-F. Controllable valley polarization using graphene multiple topological line defects. Phys. Rev. B 87, 195445. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.87.195445 (2013).

Beenakker, C. W. J. Specular andreev reflection in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 067007. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.067007 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12264059), and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant No. ZR2023MA027).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Ren.: Formal analysis, investigation and writing-original draft preparation; S.Wang.: Formal analysis and validation; M.Sun.: Data curation and validation; H.Tian: Formal analysis; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, C., Sun, M., Tian, H. et al. Valley crossed Andreev reflection in graphene periodic line defect superlattice junctions. Sci Rep 15, 15917 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01019-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01019-w