Abstract

With the increasing urbanization in China, monitoring and predicting the deformation of deep excavations has become increasingly critical. Concurrently, as neural network models find application and development in deep excavation displacement prediction, traditional models face challenges such as insufficient accuracy and weak generalization capabilities, failing to meet the high-precision warning demands of practical engineering. Therefore, research into hybrid models is necessary. This study proposes a combined neural network model integrating a Convolutional Neural Network, Long Short-Term Memory network, and Self-Attention Mechanism (CNN–LSTM–SAM), which utilizes time-series monitoring data as input. The CNN–LSTM–SAM model merges the data feature extraction capabilities of CNN, the long-term memory function of LSTM, and the information weighting capacity of the self-attention mechanism, synthesizing the advantages of various deep excavation displacement prediction models to enhance prediction accuracy and provide more effective support for construction practice. Furthermore, given the limited application of the CNN–LSTM–SAM model in deep excavation displacement analysis, this research contributes to addressing gaps in this field. Applied to an internally braced deep excavation project in the Donggang Business District of Dalian, displacement data acquired through Distributed Fiber Optic Sensing (DFOS) technology were used as training data. The CNN–LSTM–SAM model was employed to predict the horizontal displacement at the pile top. The resulting deformation predictions were compared and analyzed against those from Back Propagation (BP) neural network, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network, and a combined Convolutional Neural Network-Long Short-Term Memory (CNN–LSTM) model. Results indicate that at monitoring point S5, the coefficient of determination (R2) for the CNN–LSTM–SAM model’s predictions increased by 12.42%, 10.85%, and 5.63% compared to the BP, LSTM, and CNN–LSTM models, respectively, demonstrating higher accuracy than the other three models. Similar patterns were observed when training and predicting using data from other monitoring points, proving the applicability and robustness of the CNN–LSTM–SAM model. The findings of this study offer valuable references for the design and construction of similar deep excavation projects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Predicting deformation in deep excavations is a core issue in geotechnical engineering safety monitoring. In recent years, Distributed Fiber Optic Sensing (DFOS) technology, known for its high spatial resolution, has been widely adopted for deformation data acquisition. However, effectively integrating DFOS data with deep learning models remains a relatively underexplored area in current research.

The application of neural networks and machine learning techniques in civil engineering is growing1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9.Given that foundation pit monitoring data are mostly time-series data (i.e., data that change over time), the LSTM neural network model has gradually been applied in the field of foundation pit monitoring and prediction. Xia et al.10 established a safety risk early warning model for deep foundation pit deformation based on this model, and case studies have demonstrated its high accuracy and superiority in deformation prediction. Xu et al.11 used several neural network models to establish prediction models of maximum lateral displacement of the support structure in different foundation pits and lateral displacement of the support structure in different working conditions of the same foundation pit, demonstrating that recurrent neural network models considering time series data outperform models that do not consider time series data. The studies12,13,14,15,16 also indicate that deformation predicted by the LSTM model had smaller errors in terms of mean absolute error (MAE), mean square error (MSE), and root mean square error (RMSE) compared to BP models and grey models. Similarly, LSTM hybrid models combined with other neural network mechanisms have higher prediction accuracy and better stability than single LSTM models.

However, existing research often focuses on optimizing single algorithms, neglecting the potential advantages of hybrid models that combine multiple approaches. Similarly, combined LSTM models incorporating other neural network mechanisms achieve higher prediction accuracy than single LSTM models and exhibit better stability17,18,19. With the development of machine learning and computer vision, CNN models, adept at extracting data features, have increasingly gained attention from professionals in the civil engineering field20,21,22. Hu et al.23 used a CNN–LSTM model to predict the settlement of surrounding underground pipelines caused by an excavation, with results showing good agreement between predicted and actual measured values. Hong et al.24 proposed a combined neural network model based on CNN–LSTM and verified it using actual engineering monitoring data, demonstrating that the combined model considering spatiotemporal correlation has higher accuracy than single models considering only temporal correlation.

With China’s rapid urbanization, the impact of deep excavation projects on the surrounding environment has become increasingly prominent. Many urban excavation sites are surrounded by dense populations, buildings, and pipelines. To avoid adverse effects on the surroundings, it is essential to control deformation during excavation construction, making the prediction of deep excavation deformation increasingly necessary. Therefore, developing highly robust prediction models is not only a requirement for theoretical innovation but also an urgent need for engineering safety.

To further improve the accuracy of excavation displacement prediction and mitigate safety risks in practical engineering, this paper integrates the Self-Attention Mechanism (SAM) with the CNN–LSTM architecture. By dynamically assigning weights to spatiotemporal features through SAM, it attempts to address the gradient vanishing problem encountered in traditional LSTM when modeling long-term dependencies. This paper proposes a combined method based on CNN, LSTM, and the SAM mechanism (CNN–LSTM–SAM) and hypothesizes that the CNN–LSTM–SAM model significantly outperforms traditional models in predicting deformation under complex geological conditions. The model first inputs the excavation displacement data into a CNN to extract spatiotemporal features, then feeds these features into the SAM part to assign weights to different displacement values, and finally uses an LSTM model to predict the excavation displacement. Predicting deformation in complex deep excavations still faces many challenges, and relying solely on traditional methods makes it difficult to accurately capture the non-linear characteristics of excavation displacement data. The CNN–LSTM–SAM model enhances feature extraction capabilities by introducing CNN and SAM, not only improving prediction accuracy but also significantly enhancing its generalization ability.

This study aims to construct a hybrid model for excavation displacement prediction based on the CNN–LSTM–SAM architecture and compare its prediction results with those of other models trained on the same dataset. This paper applies the CNN–LSTM–SAM model to predict displacement in a deep excavation project in Dalian Donggang Business District. Using four evaluation metrics, including the coefficient of determination, the predictions of the CNN–LSTM–SAM model are compared with those of BP, LSTM, and CNN–LSTM models. Through controlled variable analysis, it demonstrates that the CNN–LSTM–SAM model achieves higher prediction accuracy than the other three models, providing theoretical guidance and practical application value for engineering projects.

Overview of the CNN–LSTM–SAM model

Convolutional neural network (CNN)

CNN is a type of feedforward neural network with powerful feature extraction capabilities, commonly used in computer vision and speech processing. By treating time-series data as two-dimensional data similar to image format (time on the x-axis, data value on the y-axis), CNN can also be effectively applied to process time-series data with excellence performance.

A CNN typically consists of convolutional layers, pooling layers, and fully connected layers. The convolutional layer uses kernel functions to extract features from the data. The pooling layer performs dimensionality reduction on the data processed by the convolutional layer, thereby controlling the total number of parameters and preventing overfitting. The fully connected layer usually aggregates the extracted features at the end of the network. The structure of a CNN is shown in Fig. 1.

In a 2D CNN, the output neuron value at position \(\left(k,l\right)\) can be expressed as:

Here, \(f\left(.\right)\) is the activation function; \({\omega }_{i,j}\) represents the value of the convolution kernel at position \(\left(i,j\right)\) in the current feature map; \({x}_{c,(k+i)(l+j)}\) denotes the input data from input channel c; \({b}_{i,j}\) is the bias of the computed feature map; \({C}_{in}\) is the number of original channels (the first layer) or the number of feature maps in the previous layer (intermediate layers); H and W are the height and width of the convolution kernel, respectively.

Long short-term memory neural network (LSTM)

LSTM networks possess strong capabilities for time-series data regression and can identify long-term dependencies varying over time. By processing historical data through an LSTM network, the model can learn latent patterns and relationships between different time steps, making LSTM models valuable for predicting the deformation of excavation support structures. The structure of an LSTM neuron is shown in Fig. 2.

Its key technical feature is the gate structure, comprising three sub-structures: input gate, output gate, and forget gate. The input gate controls the entry of new information, the forget gate manages the discarding of old information, and the output gate filters information to be passed to the next cell structure, thereby regulating information flow. The gate structure endows LSTM networks with long-term memory capabilities.

Forget gate formula:

Here, \({W}_{f}\) is the weight matrix of the forget gate; \({b}_{f}\) is the bias threshold vector; \(\sigma\) is the sigmoid activation function; and \({f}_{t}\) is the output vector of the forget gate.

Input gate formula:

Here,\({W}_{i}\) is the weight matrix of the input gate used for linear transformation; \({b}_{i}\) is the threshold vector.

The candidate value \({\widetilde{c}}_{t}\) and the updated memory cell value \({c}_{t}\) are calculated as:

Here \({W}_{C}\) is the weight matrix used for linear transformation in the neural network; \({b}_{C}\) is the threshold vector; \(\text{tanh}\) is the hyperbolic tangent activation function; \({c}_{t-1}\) represents the long-term memory from the previous time step.

Self-attention mechanism (SAM)

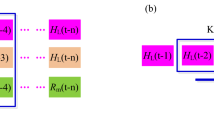

The core idea of the self-attention mechanism is to enable network nodes to focus on critical information at specific times25 and suppress irrelevant information, thereby improving prediction accuracy while ensuring input and output data dimensions remain unchanged. SAM is a variant of the attention mechanism26 and excels at capturing internal correlations within input data. Experiments show that adding it to LSTM networks can effectively enhance network accuracy and robustness27,28. Introducing SAM aims to understand the importance of temporal data at different stages of excavation deformation. The structure of the self-attention mechanism is shown in Fig. 3.

Its primary mechanism involves mapping the input into different spaces to obtain query (Q), key (K), and value vectors. It then calculates the correlation coefficients between Q and K and obtains attention weights through softmax normalization. Finally, these attention weights are used to weight the corresponding value vectors, which are then summed to produce the output vector. The relevant formulas are as follows:

Attention score formula:

Attention weight formula:

Output vector formula:

Here, \({a}^{i}\) is the input vector; \({q}^{i}\) is the query vector; \({k}^{i}\) is the key vector; \({v}^{i}\) is the value vector; and \({\text{W}}^{\text{q}}\), \({\text{W}}^{\text{k}}\), and \({\text{W}}^{\text{v}}\) are the corresponding parameters to be determined.

CNN–LSTM–SAM model

The structure of the CNN–LSTM–SAM neural network model proposed in this paper is shown in Fig. 4. The input data represents the monitoring values at a certain monitoring point over a time range t. By treating the time-series data as 2D data (time on x-axis, value on y-axis), CNN can effectively process it. The input time-series data, after passing through a sequence folding layer that converts the image sequence into images, is processed independently at each time step by convolutional operations. The output from the sequence folding layer enters the CNN part, flowing into the first convolutional layer with a kernel size of1,2 and 32 feature maps. This is followed by a Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) layer and then a second convolutional layer with a kernel size of1,2 and 64 feature maps. These layers extract feature parameters from the data. The sliding window size used was initially determined based on relevant literature with similar dataset sizes and then fine-tuned manually. Multiple runs confirmed its suitability for the dataset used in this paper, achieving relatively high accuracy.

To eliminate the channel dimension while preserving spatial dimensions, a dimension permutation (transpose) layer is needed. After this layer, global average pooling and global max pooling layers are set up in parallel. These pooling layers perform dimensionality reduction on the data processed by the convolutional layers, controlling parameter count and preventing overfitting. Information processed by the parallel pooling layers is then passed through a concatenation layer. Finally, another dimension permutation layer restores the original dimensions before flowing into a third convolutional layer with a kernel size of [1, 1] and 1 feature map for channel number transformation. The SAM part receives two inputs: data from the third convolutional layer passes through a sigmoid function, bounding the output between (0, 1). This output is then matrix-multiplied element-wise with the output of the second convolutional layer, effectively assigning attention weights to reinforce important information from the second layer’s output.

A sequence unfolding layer restores the sequence structure of the input data after sequence folding. In this model, the sequence unfolding layer has two input paths. One path processes data through the CNN and SAM parts for information enhancement. The other path bypasses the SAM part and directly unfolds the sequence for prediction. Data from both paths are flattened using a flatten layer, collapsing spatial dimensions into the channel dimension.

An LSTM layer performs multi-step rolling processing on the output, passing the predicted feature parameters from the previous layer to the next layer (the fully connected layer). Before obtaining the final predicted monitoring data, the feature parameter predictions are processed through the fully connected layer, which then outputs the results.

Given the limited dataset size in this study, manual parameter tuning was feasible for the CNN–LSTM–SAM model. However, this method has significant limitations for larger datasets. For studies involving larger datasets or more variables, automated hyperparameter optimization methods (e.g., Bayesian optimization, or possibly “Fourier tuning” as mentioned, though less common) could improve efficiency. It should be noted that the CNN–LSTM–SAM model architecture presented here is not limited to predicting excavation displacement; theoretically, it can be used to predict other types of time-series data, such as slope displacement, offering broader reference value for academia and engineering practice.

Engineering example

Project overview

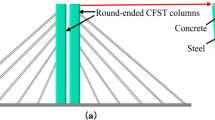

The deep excavation project in Dalian’s Donggang Business District covers an area of approximately 100 m × 50 m and includes a three-level basement facility. The excavation depth ranges from 14.0 to 15.7 m, with an excavation area of about 5150 m2. The support system consists of contiguous bored piles with two levels of reinforced concrete internal bracing. The design includes diagonal bracing on the south side and ring bracing on the north side. The retaining piles are contiguous bored piles with a diameter of 0.6 m. A cross-section of the excavation support system is shown in Fig. 5.

The strata on the site of this project are in sequence from top to bottom: plain fill, mucky silty clay, silty clay, completely weathered slate, intensely weathered slate, moderately weathered slate, and slightly weathered slate. In terms of the engineering example of the adjacent parallel field, the water level elevation of groundwater in the surrounding area of the site reaches 1.80 m. Its main aquifer is earth fill, which is a strong permeable stratum. The cross-section of the foundation pit support system is illustrated in Fig. 6.

Monitoring arrangement for the deep foundation pit

After reviewing the relevant regulations, site conditions, and support plans, the decision was made to monitor support deformation and ground settlement. The routine monitoring items are as follows:

-

1.

Inclination measurement of support piles (CX1–CX7).

-

2.

Ground surface settlement monitoring (DB1–DB17).

-

3.

Monitoring of horizontal displacement at the top of piles (S1–S15).

Inclinometers combined with DFOS technology were used to monitor the horizontal displacement at the top of the support piles. Seven horizontal displacement monitoring points (CX1–CX7) were installed at the corners and midpoints of the long sides of the retaining structure, with a horizontal distance between points not exceeding 50 m.

Ground settlement monitoring points (DB1–DB17) were arranged around the excavation perimeter in adjacent green belts and sidewalks.

Fifteen horizontal displacement monitoring points (S1–S15) were set up at the top of the piles.

This study focuses on data from monitoring points S5 (pile top horizontal displacement), DB9, and DB11 (surface settlement). Data spanning 120 periods were collected for each point.

Arrangement of distributed optical fiber monitoring

To cope with harsh construction conditions like backfilling and grouting, tight-buffered optical fiber technology was employed. This technology offers better encapsulation protection and strain transfer efficiency, making it suitable for adverse working environments and widely used in deep excavation site monitoring. This method enables continuous distributed monitoring and analysis of the overall strain behavior of the measured object by collecting data (such as damage, temperature, and strain) at any point along the fiber. In this project, DFOS was used to monitor the horizontal displacement at the top of the support piles. To meet the design requirements, the retaining piles had a diameter of 1.2 m and a length of 32 m.

This study utilized DFOS for real-time monitoring of the retaining piles in the northwest section of the excavation. A schematic diagram of the field test setup for the deep excavation support structure is shown in Fig. 7.

Technical issues such as the layout plan needed resolution to ensure fiber survival rate, ease of installation, and monitoring accuracy. At least four sensor cables were installed inside each bored pile, laid along the inner side of the reinforcement cage to avoid damage during concrete pouring. A dual U-shaped layout method was adopted to ensure fiber survivability and data reliability.

After fabricating the reinforcement cage, the main reinforcing bars were polished and cleaned with alcohol. Tight-buffered fibers were attached at the designated positions using cyanoacrylate adhesive (502 glue), keeping the fibers taut during installation. Metal conduits were used to protect the fibers at bends. At the pile head, the fiber section was connected to a steel pipe section, and the fiber was secured to prevent damage to the reinforcement cage during lifting.

Metal-based armored (cable-like) optical fibers offer controllable strain transfer effects and good encapsulation technology. To prevent contact between the fibers and the soil/rock mass or grouting equipment, they were symmetrically arranged along the main reinforcement bars on the inner side of the cage. On-site operations for the fiber optic monitoring scheme are shown in Fig. 8.

Monitoring instruments

Fiber optic data were collected using the NBX-8100 optical interrogator manufactured by Neubrex Co., Ltd. (Japan), which employs Brillouin Optical Time Domain Reflectometry (BOTDR) technology. This device, introduced in 2018, represents the high-end, cutting-edge technology in the international distributed fiber optic sensing industry. It features automatic calibration and scanning functions, significantly improving testing efficiency and accuracy. With advantages like high resolution, high sensitivity, and high speed, it is widely used in optical communication, fiber optic sensing, spectral analysis, and other fields. Its specifications met the experimental requirements. The its parameters are listed in Table 1.

The sensor cable used in the experiment was the NZS-DSS-C02 model strain sensing cable. It is designed for use with BOTDR technology and includes multiple metal strength members, significantly increasing its surface strength. Measurement results can be directly converted to displacement, ensuring the accuracy of the experimental results. The performance parameters of the sensor cable are shown in Table 2.

Analysis of monitoring results

Figure 9 shows the strain monitoring data from the inner and outer sides of the excavation pit. The left side represents the inner fiber, and the right side represents the outer fiber. Due to lateral earth pressure, the pile body deformed, generating tensile and compressive strains on the inner and outer sides of the pit, respectively.

On March 8th, before the internal bracing was cast, the support piles bore the external earth pressure, resulting in tensile strain in the outer fibers and compressive strain in the inner fibers. On March 29th, after the first level of internal bracing was cast and the second stage of excavation commenced, the support piles began to deform inwards near the excavation face. As the internal bracing took up part of the earth pressure, compressive strain developed on the outer side of the pile, and tensile strain developed on the inner side. The monitoring results indicate that as the excavation proceeded, the stress state on the inner and outer sides of the support structure reversed. The internal bracing clearly shared the load from the support piles, and the earth pressure load it carried continuously increased. However, its axial support force remained within safe limits, indicating the high safety level of the internal bracing structure.

Figure 10 compares the deep horizontal displacement at section 1–1 measured by the inclinometer and DFOS. When the excavation reached the bottom at − 9.5 m, the maximum deep horizontal displacement measured by the inclinometer was 13.16 mm, occurring at a depth of − 10.78 m. The maximum displacement measured by DFOS was 11.32 mm, occurring at − 12.53 m. It can be observed that the variation trends of both methods are generally similar.

The fiber optic monitoring data are generally close to the inclinometer data. The sampling interval for the inclinometer data is 0.5 m, which is ten times that of the DFOS monitoring. DFOS essentially achieves monitoring of structural deformation characteristics within very small ranges of the measured object. This facilitates the study of subtle changes in the excavation support structure under the influence of external loads, construction machinery, etc., and exploration of its deformation mechanism. However, accurate monitoring with optical fibers requires good encapsulation technology and proper installation methods.

Based on the weekly monitoring reports for the Dalian’s Donggang Business District deep excavation project, this study focuses on the deformation at pile top horizontal displacement monitoring point S5 and surface settlement monitoring points DB9 and DB11. Prediction results from February 26, 2021, to May 6, 2022, were compiled.

The 120 periods of pile top horizontal displacement/surface settlement data recorded at the three monitoring points are shown in Fig. 12.

For point S5, the pile top horizontal displacement increased slowly in the initial monitoring period (periods 1–30), followed by a step-like increase (periods 30–50). Subsequently (periods 50–85), the displacement generally remained unchanged. As monitoring continued (periods 85–120), the displacement gradually showed a trend of faster increase.

For point DB9, surface settlement increased relatively rapidly in the initial period (periods 1–30). As monitoring progressed (periods 30–60), the settlement increase tended to stop for a period around 11 mm, with occasional fluctuations. Later (periods 60–80, Note: original text says 30–80, check consistency with Fig. 11), the trend of faster increase resumed, and finally (periods 80–120), it maintained a slow increasing trend.

For point DB11, surface settlement increased slowly initially (periods 1–35), followed by a step-like increase over a short period (periods 35–45). Subsequently (periods 45–80), the surface settlement generally remained unchanged. Finally (periods 80–120), it resumed a slow increasing trend, with occasional anomalous values. The overall trend was slow growth.

Deformation prediction based on CNN–LSTM–SAM model

Preprocessing of prediction model input value

During excavation, data variations at the same monitoring point within the same construction cycle often exhibit clear correlations, making them suitable as the primary subject for predicting excavation deformation. However, due to various uncertainties such as site conditions and construction methods, the change in excavation deformation over time is often a complex non-linear relationship, which traditional regression models struggle to express accurately. The LSTM prediction model, combined with the time-series multi-step rolling method, offers unique advantages in adaptive learning, generalization ability, and processing sequential data. When inputting sample data, the deformation time-series data is preprocessed using the multi-step rolling model as follows: First, measured data from the previous 'm' periods are used as input samples to predict the deformation at period m + 1. Then, the window slides forward one step, using measured data from period 2 to m + 1 as input to predict the value at period m + 2. This process repeats, continuously updating the input values to output the prediction for the latest period, thus achieving multi-step real-time rolling prediction. In this case study, the specific preprocessing method was: the 120 periods of monitoring data, arranged chronologically, were divided into 115 groups. Group 1: data from periods 1–5 predict period 6; Group 2: data from periods 2–6 predict period 7, and so on. This process did not involve standardization or scaling.

In this study, the training set was set to account for 70% of the dataset, resulting in 84 groups of training samples (120 × 70% = 84). The test set contained 31 groups of samples, calculated as 120 × 30%—5 = 31. Therefore, time-series data from periods 1 to 84 were used as the training set (84 samples), and data from periods 85 to 120 were used as the test set (31 samples).

Evaluation index of CNN–LSTM model

The Coefficient of Determination (R2), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Mean Bias Error (MBE) were introduced as mathematical indicators to evaluate the accuracy of the CNN–LSTM–SAM model. The calculation formulas are as follows:

Here, \(n\) is the number of data periods; \({y}_{i}\) is the measured value; \(\overline{y }\) is the average measured value; \({\widehat{y}}_{i}\) is the predicted value.

The R2 value range from 0 to 1; a value closer to 1 indicates a better fit between the predicted and measured curves, signifying better prediction performance. Larger values of RMSE, MAE, and MBE indicate larger errors; values closer to 0 indicate better prediction performance.

Analysis of forecasting results

This study focuses on predicting the pile top horizontal displacement at monitoring point S5 and surface settlement at points DB9 and DB11. The CNN–LSTM–SAM model used contained two convolutional layers: the first with a kernel size of [2, 1] and 32 feature maps, the second with a kernel size of [2, 1] and 64 feature maps. The model employed the Adaptive Moment Estimation (Adam) optimization algorithm with an initial learning rate of 0.01, a learning rate drop factor of 0.1, and a learning rate drop period of 700. The maximum number of training epochs was 1,000, and the dataset was shuffled before each epoch. The LSTM layer had 20 neurons. The input layer count for the attention multiplication segment was 2. MATLAB R2022b was used for plotting the final deformation prediction results.

To compare the prediction performance of the CNN–LSTM–SAM model, the same training set was imported into BP, LSTM, and CNN–LSTM models for training and subsequent displacement prediction. The principle of the BP neural network involves forward propagation of signals processed through input and hidden layers; if the output error compared to the actual value is too large, the error is propagated backward to adjust the weights of each layer.

Prediction of pile top horizontal displacement for point S5 was performed. Examples of the measured value training samples are shown in Table 3.

The prediction results are shown in Figs. 12 and 13. It can be observed that all four models showed high fitting accuracy with the measured value curve in the early prediction stages. As the prediction period increased, the BP and LSTM prediction curves gradually deviated below the measured curve, while the CNN–LSTM prediction curve tended to deviate above it. The CNN–LSTM–SAM prediction curve, although fluctuating around the measured curve, generally maintained a high degree of fit, with stable overall error and clear trend, indicating good prediction performance. The relative errors of the four models showed a trend of CNN–LSTM–SAM < CNN–LSTM, and also CNN–LSTM–SAM < LSTM < BP. Since the deviations were in different directions, a precise comparison between BP, LSTM, and CNN–LSTM requires analysis of numerical indicators.

For the BP model, the relative error ranges from − 7.73 to 1.70%, with an average of − 2.58%. For the LSTM model, the range is − 7.26 to 3.18%, averaging − 1.43%. For the CNN–LSTM model, the range is − 1.28 to 5.41%, averaging 2.17%. For the CNN–LSTM–SAM model, the range is − 4.09 to 2.46%, averaging − 0.12%. The prediction relative error of the CNN–LSTM–SAM model is considered within a reasonable range. The relative error range for the CNN–LSTM–SAM model (6.55%) is smaller than that of the CNN–LSTM model (6.69%). Furthermore, the absolute average relative error of the CNN–LSTM–SAM model (0.12%) is also lower than that of the CNN–LSTM model (2.17%), demonstrating that the CNN–LSTM–SAM model’s prediction accuracy is higher than the CNN–LSTM model. Comparison indicates that the CNN–LSTM–SAM model has the smallest relative error range and average relative error magnitude, confirming its highest prediction accuracy among the four models.

The evaluation metrics for the four models predicting settlement at point S5 are shown in Table 4. The coefficient of determination (R2) for the CNN–LSTM–SAM model increased by 12.42%, 10.85%, and 5.63% compared to the BP, LSTM, and CNN–LSTM models, respectively. The prediction accuracy ranking is: CNN–LSTM–SAM > CNN–LSTM > LSTM > BP. This conclusion aligns with observations from the prediction and error curves and satisfies the general finding that CNN–LSTM > LSTM > BP. Therefore, it is concluded that the CNN–LSTM–SAM model provides superior accuracy in predicting surface settlement at point S5 compared to the other three models. Through controlled variable comparison between CNN–LSTM–SAM and CNN–LSTM, the improvement in prediction accuracy is attributed to the SAM mechanism addressing the gradient vanishing problem in traditional LSTM for long-term dependency modeling.

Further analysis of model rationality

In order to verify the stability and robustness of the CNN–LSTM–SAM model, monitoring data from points DB9 and DB11 were selected. The CNN–LSTM–SAM model was used to predict surface settlement at DB9 and DB11, and its predictive performance was further studied by analyzing its fitting degree for different types of numerical data.

Prediction of surface settlement for point DB9 was performed. Examples of the measured value training samples are shown in Table 5.

The prediction results are shown in Figs. 14 and 15. In the initial prediction stage, the BP model exhibited smaller errors compared to the other three models. It is speculated that this occurred because the initial number of samples was small, limiting the data extraction capability of the CNN component. However, as the amount of data increased, the model could better extract data features, and prediction errors gradually decreased. As the prediction period increased, the relative errors of the CNN–LSTM and CNN–LSTM–SAM models gradually approached and became lower than those of the single BP and LSTM models. Their overall errors were stable, trends were clear, and prediction performance was good. The relative errors of the four models showed a trend of CNN–LSTM–SAM < CNN–LSTM < LSTM < BP over time.

For the BP model, the relative error ranged from − 3.00 to 0.35%, averaging − 1.39%. For the LSTM model, the range was − 2.87 to 1.45%, averaging − 0.96%. For the CNN–LSTM model, the range was − 1.99 to 2.40%, averaging − 0.34%. For the CNN–LSTM–SAM model, the range was − 1.22 to 2.22%, averaging 0.09%. The CNN–LSTM–SAM model’s relative error is considered within a reasonable range. Its relative error range (3.44%) was smaller than that of the CNN–LSTM model (4.39%). The absolute average relative error (0.09%) was also lower than that of the CNN–LSTM model (0.34%), confirming higher prediction accuracy for the CNN–LSTM–SAM model. Comparison shows the CNN–LSTM–SAM model had the smallest relative error range and average magnitude, indicating the highest accuracy among the four models.

The evaluation metrics for the four models predicting settlement at point DB9 are shown in Table 6. The R2 for the CNN–LSTM–SAM model increased by 18.40%, 14.64%, and 6.23% compared to the BP, LSTM, and CNN–LSTM models, respectively. The prediction accuracy ranking is: CNN–LSTM–SAM > CNN–LSTM > LSTM > BP. This conclusion aligns with the prediction and error curve observations and the general finding that CNN–LSTM > LSTM > BP. Therefore, the CNN–LSTM–SAM model is considered more accurate for predicting surface settlement at point DB9 than the other three models. The evaluation metrics for the four models predicting settlement at point DB9 are shown in Table 6. The R2 for the CNN–LSTM–SAM model increased by 18.40%, 14.64%, and 6.23% compared to the BP, LSTM, and CNN–LSTM models, respectively. The prediction accuracy ranking is: CNN–LSTM–SAM > CNN–LSTM > LSTM > BP. This conclusion aligns with the prediction and error curve observations and the general finding that CNN–LSTM > LSTM > BP. Therefore, the CNN–LSTM–SAM model is considered more accurate for predicting surface settlement at point DB9 than the other three models.

To predict the surface subsidence of measuring point DB11, training samples of field monitoring value are shown in Table 7.

The prediction results are shown in Figs. 16 and 17. It can be seen that the prediction curves were influenced by anomalous measured values. Initially, the BP prediction curve showed a better fit to the measured curve than the other three models. As the prediction period increased, the BP model’s prediction exhibited abrupt changes following anomalies in the measured data. In contrast, the LSTM, CNN–LSTM, and CNN–LSTM–SAM models demonstrated better performance in terms of relative error, exhibiting stable overall error (except during the anomalous data segment), clear trends, and good prediction performance. Over time, the relative errors generally followed the trend: CNN–LSTM–SAM < CNN–LSTM < LSTM < BP.

For the BP model, the relative error ranged from − 3.65 to 1.86%, averaging − 1.30%. For the LSTM model, the range was − 3.22 to 2.64%, averaging − 0.11%. For the CNN–LSTM model, the range was − 2.62 to 2.16%, averaging 0.12%. For the CNN–LSTM–SAM model, the range was − 2.26 to 1.96%, averaging 0.07%. The CNN–LSTM–SAM model’s relative error is within a reasonable range. Its relative error range (4.22%) was smaller than that of the CNN–LSTM model (4.78%). The absolute average relative error (0.07%) was also lower than that of the CNN–LSTM model (0.12%), confirming higher prediction accuracy for the CNN–LSTM–SAM model. Comparison shows the CNN–LSTM–SAM model had the smallest relative error range and average magnitude, indicating the highest accuracy among the four models.

The evaluation metrics for the four models predicting settlement at point DB11 are shown in Table 8 (Note: Original text says Table 6, corrected to Table 8 based on sequence). The R2 for the CNN–LSTM–SAM model increased by 14.80%, 9.33%, and 2.86% compared to the BP, LSTM, and CNN–LSTM models, respectively. The prediction accuracy ranking is: CNN–LSTM–SAM > CNN–LSTM > LSTM > BP. This conclusion aligns with the prediction and error curve observations and the general finding that CNN–LSTM > LSTM > BP. Therefore, the CNN–LSTM–SAM model is considered more accurate for predicting pile top horizontal displacement (Note: original says pile top horizontal displacement here, but DB11 is surface settlement, corrected) surface settlement at point DB11 than the other three models.

Conclusion

This study, set against the backdrop of a deep excavation project in Dalian Donggang Business District, proposed a displacement prediction method based on a CNN–LSTM–SAM neural network. By comparing prediction results with measured data and three benchmark models (BP, LSTM, CNN–LSTM), the model’s performance was systematically evaluated, leading to the following core conclusions:

-

(1)

Based on surface settlement data from monitoring point S5 in the Dalian Donggang Business District, this study compared the predictive performance of the CNN–LSTM–SAM model against BP, LSTM, and CNN–LSTM models. Results showed that the CNN–LSTM–SAM model’s coefficient of determination (R2) increased by 12.42% compared to BP, 10.85% compared to LSTM, and 5.63% compared to CNN–LSTM. The advantage of the CNN–LSTM–SAM model stems from the synergistic effect of the CNN module’s ability to extract spatial distribution features, the LSTM module’s capacity to model temporal dependencies, and the SAM mechanism’s dynamic weighting of key information, which collectively significantly enhance prediction accuracy under complex conditions.

-

(2)

To validate the model’s generalization ability, cross-point validation experiments were conducted using data from monitoring points DB9 and DB11. Results indicated that the fluctuation range of prediction errors for the CNN–LSTM–SAM model was significantly smaller than that of traditional models. This finding confirms the model’s robustness in multi-source data scenarios, with its performance advantages consistent with the conclusions from point S5, suggesting that the SAM mechanism provides strong adaptability to local noise and data anomalies.

-

(3)

It should be noted that the adaptability of different prediction models varies across different datasets, potentially leading to biased prediction results. Therefore, when predicting displacement in actual excavation projects, a case-by-case analysis is necessary. Multiple factors should be considered to select the most suitable prediction model for the current dataset, followed by continuous adjustment and optimization to maximize prediction accuracy.

-

(4)

This study only demonstrates the applicability of the CNN–LSTM–SAM prediction model to the stratigraphic conditions of the specific internally braced deep excavation project in Dalian’s Donggang Business District. Generalizing its application to other geological conditions requires further research incorporating more practical engineering case studies.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Vanke but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Vanke. If editors or experts require certain data, they can contact us through the corresponding author’s email.(zhaojie_gd@163.com)

References

Shehadeh, A. et al. An expert system for highway construction: Multi-objective optimization using enhanced particle swarm for optimal equipment management. Expert Syst. Appl. 249, 123621 (2024).

Shehadeh, A., Alshboul, O. & Tamimi, M. Integrating climate change predictions into infrastructure degradation modelling using advanced Markovian frameworks to enhanced resilience. J. Environ. Manag. 368, 122234 (2024).

Shehadeh, A., Alshboul, O. & Saleh, E. Enhancing safety and reliability in multistory construction: A multi-state system assessment of shoring/reshoring operations using interval-valued belief functions. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 252, 110458 (2024).

Shehadeh, A. et al. Enhanced clash detection in building information modeling: Leveraging modified extreme gradient boosting for predictive analytics. Results Eng. 24, 103439 (2024).

Alshboul, O., Shehadeh, A. & Almasabha, G. Reliability of information-theoretic displacement detection and risk classification for enhanced slope stability and safety at highway construction sites. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 256, 110813 (2025).

Alshboul, O. & Shehadeh, A. Enhancing infrastructure project outcomes through optimized contractual structures and long-term warranties. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-07-2024-0954 (2024).

Shehadeh, A. & Alshboul, O. Enhancing engineering and architectural design through virtual reality and machine learning integration. Buildings 15(3), 328 (2025).

Shehadeh, A. et al. Advanced integration of BIM and VR in the built environment: Enhancing sustainability and resilience in urban development. Heliyon 11(4), e42558 (2025).

Mostafaei, H. Modal identification techniques for concrete dams: A comprehensive review and application. Sci 6(3), 40 (2024).

Tian, X., Cheng, C. & Qizhi, P. Safety risk warning of deep foundation pit deformation based on LSTM. Earth Sci. 48(10), 3925–3931 (2023).

Changjie, X. & Xinyu, L. Lateral deformation prediction of deep foundation retaining structures based on artificial neural network. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. 58(11), 1735–1744 (2024).

Shengjie, Z. & Yong, T. Deformation prediction of foundation pit based on long short-term memory algorithm. Tunn. Constr. 42(1), 113–120 (2022).

Huajing, Z., Mingyang, Z. & Wei, L. Dynamic prediction of diaphragm wall deflection caused by deep excavation using neural network algorithm. Chin. J. Undergr. Space Eng. 17(S1), 321–327 (2021).

Ou Bin, Wu. et al. LSTM-based deformation prediction model of concrete dams. Adv. Sci. Technol. Water Resour. 42(01), 21–26 (2022).

Luo, Lu., Zhi, Li. & Qiling, Z. Optimal factor set based long short-term memory network model for prediction of dam deformation. J. Hydroelectr. Eng. 42(02), 24–35 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. The prediction of dam displacement time series using STL, extra-trees, and stacked LSTM neural network. IEEE Access 8, 94440–94452 (2020).

Juncheng, L., Yong, T. & Shengjie, Z. Multi-step prediction of excavation deformation of subway station based on intelligent algorithm. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. (Chin. Ed.) 58(7), 1108–1117 (2024).

Longan, W. et al. Discussion on prediction on model of foundation pit deformation based on ARIMA and deep learning. Mine Surv. 49(5), 54–59 (2021).

Jiangu, Q., Anhai, W. & Jun, J. Prediction for nonlinear time series of geotechnical engineering based on wavelet-optimized LSTM-ARMA Model. J. Tongji Univ. 49(08), 1107–1115 (2021).

Tao, Li., Jiajun, S. & Yanlong, W. Horizontal deformation prediction of deep foundation pit support piles based on decomposition methods model. Rock Soil Mech. 45(S1), 496–506 (2024).

Tang Haoran, Hu. et al. Time series prediction of surface displacement induced by excavation of foundation pits based on deep learning. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 46(S2), 236–241 (2024).

Qing, F. et al. application of the variational mode decomposition-based CNN–LSTM model in predicting excavation deformation. Mech. Eng. 46(5), 1015–1022 (2024).

Shengxiang, Hu. & Shijun, W. A deeplearning model of surrounding pipeline settlement caused by foundation pit construction. South China J. Seismol. 43(2), 165–173 (2023).

Yuchao, H., Jiangu, Q. & Yuanxin, Ye. Application of CNN–LSTM model based on spatiotemporal correlation characteristics in deformation prediction of excavation engineering. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 43(S2), 108–111 (2021).

Jimmy Ming-Tai, W. et al. A graph-based CNN–LSTM stock price prediction algorithm with leading indicator. Multimed. Syst. 29(3), 1751–1770 (2023).

Tengxi, W. Research on forecasting and risk measurement of internet money fund returns based on error-corrected 1DCNN–LSTM–SAM and VaR: Evidence From China. IEEE Access 11, 94205–94217 (2023).

Han, S. & Dong, H. A temporal window attention-based window-dependent long short-term memory network for multivariate time series prediction. Entropy 25, 10 (2023).

Zheng, H. et al. A hybrid deep learning model with attention-based conv-LSTM networks for short-term traffic flow prediction. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 22(11), 6910–6920 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yanli Peng is responsible for designing the experimental approach, directly participating in the experimental process, and analyzing and summarizing the experimental results. Jie Zhao is responsible for providing the basic experimental parameters and offering guiding suggestions on the experimental design. During the experiment,Jie Zhao plays a supervisory and leadership role. Yijiang FAN is responsible for organizing the experimental process, including editing it into an article and creating charts and graphs. Cheng FAN is responsible for the final revision of the article, including ensuring the fluency of the sentences and the professionalism of the wording.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, Y., Zhao, J., Fan, Y. et al. Monitoring and deformation of deep excavation engineering based on DFOS technology and hybrid deep learning. Sci Rep 15, 16042 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01120-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01120-0