Abstract

Pipe-framed solar greenhouses are susceptible to structural failure under extreme snow loads due to their inherent structural asymmetry. This study investigated the failure mechanisms of a 10 m-span pipe-framed greenhouse and proposed three reinforcement methods (reinforced by one brace, lattice column, and temporary column) to enhance snow resistance. A novel concept of reinforcement efficiency was proposed to optimize retrofitting decisions. Finite element (FE) analysis reveals that structural failure originates from full-section yielding of the north column caused by excessive bending moments. Among reinforcement methods, installing a temporary column 4.5 m from the south roof end (near mid-span) achieves the highest reinforcement efficiency (365.3% and 437.1% under uniform and non-uniform snow loads, respectively), followed by replacing single-tube columns with lattice columns (59.9% and 63.1% under uniform and non-uniform snow loads, respectively). Bracing between the south roof and column enhances stability, whereas bracing connecting the south and north roofs accelerates failure and should be avoided. It is recommended to set up one temporary column only under extreme snow loads. The north column of pipe-framed solar greenhouses should be designed as a lattice column. Additionally, flat elliptical hollow sections exhibit superior flexural rigidity compared to rectangular or hat-shaped sections under equivalent steel consumption. This study can provide references for the snow resistance design of other similar pipe-framed greenhouses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Greenhouses are agricultural facility that provides a favourable growing environment for plants under controlled conditions1. One of the purposes of greenhouse structural design is to enable adequate structural safety2,3. Greenhouse structures are often characterized by light weight and high flexibility, which make them sensitive to variable loads4,5. With the frequent occurrence of meteorological disasters, such as heavy snows and strong winds, the number of greenhouse structure collapses is increasing6,7,8. Therefore, the structural safety of greenhouses under extreme weather, regardless of their design or running states, is receiving increasing attention.

According to greenhouse’s geometric configurations, greenhouses are primarily categorized into two structural systems: symmetric structures (e.g., even-span type greenhouse) and asymmetric structures (e.g., solar greenhouses, uneven-span type greenhouse)9. Symmetric greenhouses, characterized by uniform load distribution and bilateral symmetry, have been widely studied for their mechanical behaviors through field tests10,11, scaled-down experiments12, and numerical analyses13,14,15,16,17. In terms of even-span vaulted-roof greenhouses, Kim18 performed field tests to investigate the effects of pipe connectors, rafter spacing, and embedding depth on the uplift resistance of plastic greenhouse with continuous-pipe-foundation. Lee and Ryu19 numerically investigated the collapse mechanism of pipe-framed plastic greenhouses considering the semi-rigid behavior of the cross-over connections. Wang et al.20 developed a 3D FE model to investigate the static and dynamic characteristics of a large-span insulated plastic greenhouse composed of primary and secondary portal frames. Similar with even-span vaulted-roof greenhouses, studies on even-span pitched-roof greenhouses also mainly focus on the static analysis21,22,23,24, dynamic analysis25, and field vibration tests26. The above studies showed that for even-span pipe-framed greenhouses, the members are mainly subjected to bending moments. These findings can provide references for the design and analysis of even-span pipe-framed greenhouses.

Asymmetric solar greenhouses, as shown in Fig. 1, optimized for passive solar energy utilization, exhibit distinct structural mechanics that differ fundamentally from symmetric configurations. This inherent asymmetry induces complex load transfer pathways, elevating risks of localized failure modes. To address these challenges, recent studies have systematically investigated their mechanical behaviors through field tests and FE modeling. The earliest corresponding field tests was conducted by Bai et al.27. Recently, studies on the static properties under snow loads28,29,30, and dynamic responses under wind loads31,32,33 of asymmetric solar greenhouses have been extensively investigated by FE methods. These studies provide a sound basis for the structural design and optimization of asymmetric solar greenhouses.

However, the above studies are all based on improving the disaster resistance of greenhouses in the design stage, and are of little help to the disaster relief of existing greenhouses. For improving the disaster resistance of existing greenhouses, many types of reinforcement strategies have been employed, such as adding braces or tension ties, reinforcing sections with welding plates or fiber reinforced polymers34. Uematsu and Takahashi35,36 explored the impact of adding braces on improving the wind and snow resistance of even-span vaulted-roof greenhouses. A study by Moriyama et al.37 showed that adding two braces significantly increased the maximum allowable snow load, which in turn could reduce the steel consumption. Testing results obtained by Lee et al.38 showed that setting a pretension tension tie could increase the load capacity by 35-65% under symmetric vertical loads. A study by Scarascia-Mugnozza et al.39 showed that the use of tensegrity technology in single-span vaulted and duo-pitched roof greenhouses could reduce steel consumption by 9.6% and 35.2%, respectively. These aforementioned studies can provide guides for farmers improve the disaster resistance of existing greenhouses.

It is worth pointing out that the aforementioned reinforcement strategies are mainly applicable to symmetric greenhouse structures. And these findings primarily address symmetric load distributions, limiting their applicability to asymmetric solar greenhouses. Recent studies on asymmetric solar greenhouses highlight unique snow accumulation patterns, with stress concentrations near the north column due to asymmetric bending28,29. Despite these advancements, three critical gaps persist: (i) existing studies focus on optimizing initial designs rather than retrofitting vulnerable structure; (ii) proposed reinforcement methods (e.g., cross-bracing, tension ties) are tailored to symmetric greenhouse structures, with limited validation for asymmetric solar greenhouse; and (iii) economic evaluations of reinforcement strategies are absent, hindering cost-effective decision-making for farmers.

To address these gaps, the FE method was employed to investigate the failure mechanisms and reinforcement of pipe-framed asymmetric solar greenhouses under snow loads. Firstly, the FE models of greenhouse were established in ANSYS. Secondly, the failure mechanisms of greenhouses with different sectional shape (flat elliptical hollow section, rectangular hollow section and hat-shaped section) were investigated, and the optimal sectional shape was selected. Thirdly, based on the failure mechanism of greenhouses, three reinforcement methods (reinforced by one brace, lattice column, and temporary column) were proposed. And the influence of these three reinforcement methods on the improvement of the ultimate bearing capacity was discussed. Finially, to comprehensively evaluate the economy and effectiveness of the three reinforcement methods, a new concept of reinforcement efficiency was proposed. And the optimal reinforcement scheme was given. The findings can provide a theoretical guidance for preventing damage to established pipe-framed asymmetric solar greenhouses under extreme snow loads. Figure 2 presents the research flow of this study.

Materials and methods

Greenhouse structure

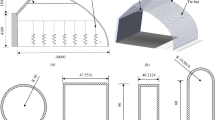

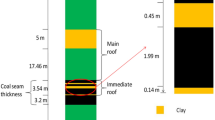

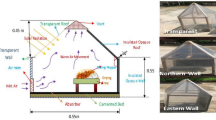

The object of this study is a typical pipe-framed solar greenhouse with a span of 10.0 m and ridge height of 5.5 m, as shown in Fig. 3. The main load-bearing structure of the greenhouse include a south roof, a north roof and a north column. Detailed building parameters are listed in Table 1.

To explore the effect of sectional shape on the ultimate bearing capacity of the structure, three types of skeleton sections were considered: flat elliptical hollow section, rectangular hollow section and hat-shaped section, as shown in Fig. 4. The detailed sectional characteristic information is listed in Table 2. For these three types of sections, the sectional area, sectional width and wall thickness are the same.

FE model

The FE models of the greenhouses were built using ANSYS software. All the greenhouse structure members were made of galvanised cold-formed thin-walled steel. The steel graded was Q235. An ideal elastic-plastic model was used to simulate the constitutive model of the steel material. The yield strength was 235 MPa, the Young’s modulus was 206 GPa, the Poisson’s ratio was 0.3, and the density was 7850 kg m− 3. The BEAM189 element which can consider material and geometry nonlinearities, was adopted to simulate the greenhouse structure. The bottom ends of the structure are connected to the concrete foundation by embedded steel components. Hence, fixed boundary condition was assumed. At the support ends, all the translational and rotational degrees of freedom were restricted in the model. The connections between steel pipes in the greenhouse skeleton were modeled as rigid joints to represent the multi-bolted moment-resisting connections. This simplification aligns with prior study34 demonstrating that rigid connections effectively approximate the semi-rigid behavior of bolted joints in thin-walled steel structures under bending-dominated loading. The geometrical nonlinearity was considered through a large deformation analysis. The effects of geometrical imperfections were considered through an equivalent geometric imperfection based on the first positive linear bucking Eigen mode. To capture the post-collapse nonlinear behaviour, the arc-length method was employed.

Actions on greenhouses

Self-weight G k1

Permanent actions are actions due to the self-weight of the steel structure, the north roof and the covering material. By defining the material density and gravitational acceleration, the self-weight of the steel structure can be automatically calculated by the ANSYS software. The self-weight of the north roof is 30 N m− 2. The covering material is polyethylene film with a thickness of 0.1 mm, and the self-weight of the film is 1 N m− 2.

Permanently-present installation actions G k2

Permanently-present installation actions are actions due to permanently installed equipment. For this solar greenhouse, the permanently-present installation action was taken 70 N m− 2 in accordance with the Chinese standard GB/T 51183–201640.

Crop actions Q k3

Crop actions are actions due to plants supported by the greenhouse structure. For the greenhouse growing tomatoes, the crop actions can be taken as 150 N m− 2.

Snow actions S k

According to the Chinese standard GB/T 51183–201640, the characteristic value of the snow actions on solar greenhouses can be calculated as follows:

where Sk is characteristic value of the snow actions, µr is the snow load shape coefficients, ct is the heating influence coefficient, and s0 is the basic snow pressure. Under the action of wind, snowdrift may lead to uneven snow distribution on the roofs. Therefore, in addition to uniform snow loads, non-uniform snow loads were also considered in this study. The snow load shape coefficients of the solar greenhouse are shown in Fig. 5. For the unheated solar greenhouse, the heating influence coefficient was taken to be 1.0.

Combination of actions

Based on our previous studies28, for pipe-framed solar greenhouses located in snowpack regions (such as northeast of China), snow loads usually dominate the designs of structures. And the resistance of pipe-framed solar greenhouses to wind loads is higher than that to snow loads. In addition, the main aim of this study was to explore the failure mechanisms of pipe-framed solar greenhouses under snow loads and propose reinforcement methods. Therefore, the combination of actions for the greenhouse is:

where Sd is the design value of actions, γG1 is the modified partial factor of the permanent actions, Gk1 is the characteristic value of the permanent actions, γG2 is the modified partial factor of the permanently-present installation actions, Gk2 is the characteristic value of the permanently-present installation actions, ψQ3 is the combination coefficient of the crop actions, γQ3 is the modified partial factor of the crop actions, Qk3 is the characteristic value of the crop actions, γA is the modified partial factor of the snow actions, Sk is the characteristic value of the snow actions.

Model validation

To validate the accuracy of the proposed FE modelling method, comparative analyses were conducted between the present results and existing literature data. Lee et al.11 evaluated the safety of single-span greenhouses under various levels of snow load. Based on the same conditions, a structural analysis was performed using the described modeling approach in this paper. The comparison of the maximum stress between the present results and those in the literature is illustrated in Fig. 6. The comparative analysis revealed strong agreement between the present results and literature results. This demonstrates the reliability of the developed FE modelling method in simulating greenhouse structural behavior under snow loads.

Comparison of maximum stresse between the present results and those in the literature11.

Results and discussion

Failure mechanisms

The load-displacement curves of the structure under snow loads are shown in Fig. 7. For each example in the figure, the X-coordinate denotes the vertical displacement of the ridge node, and the Y-coordinate denotes the snow load. The maximum load on the load-displacement curve is the ultimate bearing capacity of the structure. Under the same load conditions, the ultimate bearing capacity of the greenhouse with flat elliptical hollow section is the highest, followed by the hat-shaped section and the rectangular hollow section is the smallest. The main reason for this phenomenon is that the moment of inertia of the flat elliptical section along the strong axis is greater than that of the hat-shaped section and the rectangular hollow section (as listed in Table 2). For the same reason, the ultimate bearing capacity of the greenhouse with hat-shaped section is close to that of the greenhouse with hollow rectangular section. A similar phenomenon was also founded in the auther’s previous study41. Under uniform snow load, the ultimate bearing capacities of the greenhouse skeleton with flat elliptical hollow section, hat-shaped cross-section and rectangular hollow section are 546.6 N m− 2, 491.8 N m− 2 and 485.3 N m− 2, respectively. Under non-uniform snow load, the ultimate bearing capacities of the greenhouse skeleton with flat elliptical hollow section, hat-shaped cross-section and rectangular hollow section are 178.2 N m− 2, 170.0 N m− 2 and 168.6 N m− 2, respectively. From the above results it can be concluded that when the amount of steel is the same, it is recommended to give priority to the flat elliptical hollow section. A similar conclusion was also reached by Liu et al.42, who compared the safety performances of greenhouse skeletons with circular hollow section, rectangular hollow section, hat-shaped section and flat elliptical hollow section. In addition, comparing Fig. 7a and b, we can find that the ultimate bearing capacities of the greenhouse skeleton with flat elliptical hollow section, hat-shaped cross-section and rectangular hollow section under uniform snow load are about 3.1, 2.9 and 2.9 times that under non-uniform snow load. These results mean that the greenhouse is sensitive to non-uniform snow loads. Therefore, more attention should be paid to the safety of greenhouses subjected to non-uniform snow loads.

To explore the failure process of the greenhouse under snow loads, the greenhouse skeleton with flat elliptical hollow section is selected as an example. Figure 8 shows the stress development process of the greenhouse skeleton under non-uniform snow load. Based on Fig. 7b, the failure process of greenhouses under snow loads can be classified by three stages: elastic stage (OA), elastic-plastic stage (AB) and failure stage (BC). When the snow load is less than 140.9 N m− 2 (before point A), the greenhouse skeleton is in the elastic stage. The displacement increases linearly with the increase of snow load. When the snow load increases to 140.9 N m− 2 (Fig. 8a), the greenhouse skeleton begins to enter the elastic-plastic stage. The section flanges at the corner of the south roof, at the mid-span, at the junction of the north roof and the column, and at the bottom of the column begin to yield. As the snow load continues to increase, the yield zone expands from the flange to the web. When the snow load increases to 178.2 N m− 2 (Fig. 8b), the greenhouse skeleton reaches the ultimate bearing capacity. The junction between the north roof and the column, and the bottom of the column enter the full-section yield state. Once the greenhouse skeleton reaches its ultimate bearing capacity, the displacement will continue to increase even if the snow load is reduced. When the snow load is reduced to 169.3 N m− 2 (Fig. 8c), the ridge node displacement reaches 170.7 mm. The section at the corner of the south roof, at the mid-span, at the junction of the north roof and the column, and at the bottom of the column all enter the full-section yield state, leading to the greenhouse skeleton failure.

To further explore the failure mechanism of the greenhouse under non-uniform snow loads, Fig. 9 presents the axial force and bending moment distributions of the greenhouse at its peak load. From Fig. 9a, we can see that the axial force values are all negative, indicating that the greenhouse subjected to compression force. The maximum axial force occurs at the south roof end. Compared with axial force, the bending moment distribution is relatively complex. From Fig. 9b, we can see that the bending moment values at the corner of the south roof, the mid-span, the junction of the north roof and the column, and the bottom of the column are relatively large. These locations are consistent with those in Fig. 8c where full-section yield occurs. Comparing Figs. 8c and 9b, we can conclude that the main reason of the greenhouse failures may be attributed to excessive bending moment caused by snow loads.

Reinforcement methods

According to the results in Sect. "Failure mechanisms", under non-uniform snow load, the ultimate bearing capacity of the greenhouse skeleton with flat elliptical hollow section is 178.2 N m− 2, which is less than the basic snow pressure of 300 N m− 2 once in 10 years in Shenyang city. Therefore, in order to ensure the safety performance of this type of greenhouse under snow loads in Shenyang city, it is necessary to strengthen its structure. In this section, taking greenhouse skeletons with flat elliptical hollow section as examples, three reinforcement methods are proposed and their effects on the structure safety are discussed.

Reinforced by one Brace

One of the most common reinforcement methods is to add one brace between the south roof and the north roof or between the south roof and the column, as shown in Fig. 10. However, the bracing arrangement is mainly based on the builder’s experience and lacks the support of design theory. To investigate the effects of bracing position on the structure safety, the bracing arrangement method is shown in Fig. 10. The brace is 48 × 2.0 mm circular hollow section (CHS) steel tube. One end of the brace is pin connected to the south roof (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5), and the other end is pin connected to the north roof (N1, N2, N3) or the column (N4, N5). And there are 25 bracing arrangements in total. For the sake of expression, the greenhouse with bracing is named after the numbers at both ends of the brace. For example, the greenhouse model in Fig. 10 is named S4N3. The model without bracing is named original model.

Figure 11 shows the effects of bracing position on the ultimate bearing capacity of greenhouses under snow loads. The dashed line represents the ultimate bearing capacity of the original greenhouse without bracing. It can be seen from Fig. 11 that the ultimate bearing capacity of greenhouses cannot always be improved with bracing. On the contrary, when the brace is not set appropriately, it may reduce the ability of the structure to resist snow loads. Only when one end of the brace is connected to the column (S1N4, S1N5, S2N4, S2N5, S3N4, S3N5, S4N4, S4N5, S5N4, and S5N5) can the ultimate bearing capacity of the structure be increased, regardless of uniform and non-uniform snow loads. Under uniform snow load (Fig. 11a), the optimal model is S1N5, with an ultimate bearing capacity of 670.5 N m− 2, which is 22.7% higher than the original model. Under non-uniform snow load (Fig. 11b), the optimal model is also S1N5, with an ultimate bearing capacity of 217.6 N m− 2, which is 22.1% higher than the original model.

To explore the influence mechanism of the bracing on the ultimate bearing capacity of greenhouses, taking the S1N1, S1N2, S1N3, S1N4 and S1N5 models as examples, Fig. 12 compares the load-displacement curves of reinforcement models and the original model. As illustrated in Fig. 12, when the snow load is small, the displacement increases linearly as the load increases, that is, the structure is in the elastic stage. In the elastic stage, the slope of load-displacement curves of models S1N4 and S1N5 is larger than that of the original model, while the slope of models S1N1, S1N2, S1N3 is smaller than that of the original model. These phenomena indicate that the bracings of models S1N4 and S1N5 increase the initial structural stiffness of the original model, while the bracings of models of S1N1, S1N2, S1N3 reduce the initial structural stiffness of the original model. In addition, the initial structural stiffness of model S1N5 is the largest, while the initial structural stiffness of models S1N1, S1N2, S1N3 are not much different. These phenomena are consistent with the results in Fig. 11.

To further explore the influence mechanism of the bracing on the ultimate bearing capacity of greenhouses under non-uniform snow loads, taking the S1N5 model as examples, Fig. 13 presents the internal force distributions of the greenhouse at the peak load. Comparing Figs. 9 and 13, it can be found that the existence of the brace changes the internal force distribution of the greenhouse. In terms of axial force distribution, as shown in Fig. 13a, the greenhouse frame above the brace is subjected to axial tension, while the greenhouse frame below the brace is subjected to axial compression. While for the original model, the whole greenhouse frame is subjected to axial compression, as shown in Fig. 9a. In terms of bending moment distribution, as shown in Fig. 13b, the existence of the brace reduces the bending moment value of the north roof skeleton, and the maximum bending moment appears at the joint of the column and the brace.

According to the above results, we can conclude that: (1) Setting up one brace does not always improve the structure’s ability to resist snow loads. Improper bracing arrangement will reduce the ultimate bearing capacity of the greenhouse, thereby accelerate failure progress of the structure; (2) When arranging one brace, it is recommended to connect one end of the brace to the south roof and the other end to the column, and avoid connecting the brace to the north roof.

Reinforced by one lattice column

Another reinforcement method is to replace the single tube column with a lattice column on the basis of the original model. The schematic of the lattice column model of the greenhouse is shown in Fig. 14. The lattice column is CHS steel tube with the size of 48 × 2.0 mm. To facilitate the expression, the greenhouse reinforced by one lattice columns is referred as the lattice column model.

Figure 15 compares the load displacement curves of the lattice column model and the original model under uniform and non-uniform snow loads. The ultimate bearing capacity of the lattice column model is obviously greater than that of the original model under both uniform and non-uniform snow loads. Under uniform snow load, the ultimate bearing capacity of the lattice column model is 984.7 N m− 2, representing an increase of 80.2% compared to the original model. Under non-uniform snow load, the ultimate bearing capacity of the lattice column model is 326.9 N m− 2, representing an increase of 83.4% compared to the original model.

To explore the influence of the lattice column on the stiffness of the greenhouse, Fig. 16 shows the deformed shapes of the original model and the lattice column model under non-uniform snow load. As shown in Fig. 16, under the same load, the deformation of the lattice column model is significantly smaller than that of the original model. This phenomenon is consistent with the results in Fig. 15, in which the slope of the load displacement curve of the lattice column model is clearly greater than that of the original model. In particular, there is almost no deformation in the north roof and the column of the lattice column model. This is due to the fact that the stiffness of the greenhouse structure significantly improves when the lattice column replaces the single tube column. As a result, smaller structural displacements and improved ultimate bearing capacity are achieved.

To further explore the failure mechanism of the lattice column model under non-uniform snow load, Fig. 17 presents the von Mises stress distribution of the greenhouse at the peak load. As depicted in Fig. 17, under the peak load, the section flanges at the corner of the south roof, at the mid-span, and at the bottom of the column entered to yield. While fully sectional yielding occurred at the junction of the column and the north roof. Therefore, more attention should be paid for junction of the column and the north roof.

Reinforced by one temporary column under the South roof

Before extreme snow loads come, setting up temporary columns is also a reinforcement method to improve the ultimate bearing capacity of the greenhouse. Figure 18 shows a schematic diagram of a temporary column arrangement. In Fig. 18, the horizontal distance from the temporary column to the south roof end is defined as HD. To explore the effect of the temporary column position on the ultimate bearing capacity of the greenhouse, the temporary column moved from the south roof end to the ridge in steps of 0.5 m. The temporary column is CHS steel tube with the size of 48 × 2.0 mm. Considering the detachability of the temporary column, the connection between the upper end of the column and the greenhouse skeleton was simplified to a hinge. And the column was assumed to be hinge-connected with the ground.

Figure 19 shows the effects of the temporary column position on the ultimate bearing capacity of the greenhouse under snow loads. Under uniform snow load (Fig. 19a), as HD increase, the ultimate bearing capacity of the greenhouse increases at first and then decreases. When HD = 4.5 m, the ultimate bearing capacity reaches the maximum value of 2660.1 N m− 2, which is about 4.9 times that of the original model. Under non-uniform snow load (Fig. 19b), when HD is less than 4.5 m, the ultimate bearing capacity increases with the increase of HD. When HD = 4.5 m, the ultimate bearing capacity reaches the maximum value of 995.0 N m− 2. There is almost no change in the ultimate bearing capacity when HD increases from 4.5 m to 5.0 m. When HD is greater than 5.0 m, the ultimate bearing capacity decreases with the increase of HD. Based on the above results, we can conclude that for a greenhouse with a span of 10 m, the optimal position of the temporary column is 4.5 m away from the south roof end.

Reinforcement efficiency analysis

As discussed in Sect. "Reinforcement methods", although the ultimate bearing capacity of the greenhouse structure may be improved by setting bracings, lattice columns and temporary columns, the increase in the steel amount cannot be ignored. To identify the most suitable reinforcement method, the concept of reinforcement efficiency P is introduced here:

where \(\Delta F_{cr}\) is the ultimate bearing capacity improvement factor, \(\Delta S\) is the steel amount increase factor for the greenhouse. \(\Delta F_{cr}\) is defined as:

where \(F_{cr}^r\) is the ultimate bearing capacity of the reinforcement model. \(F_{cr}^o\) is the ultimate bearing capacity of the original model.

\(\Delta S\) is defined as:

where \(S^r\) is the steel amount of the reinforcement model. \(S^o\) is the steel amount of the original model. In this study, a positive P value signifies that the reinforcement method is economical and effective. Conversely, a negative P value indicates that the reinforcement method is uneconomical. The situation, particularly in the case of a negative \(\Delta F_{cr}\) and positive \(\Delta S\), is most uneconomical, as an increase in the steel amount results in a reduction in ultimate bearing capacity.

Figure 20 shows the effect of the bracing position on reinforcement efficiency. It can be clearly seen from Fig. 20 that most reinforcement efficiencies are negative, regardless of uniform or non-uniform snow loads. Under uniform snow load (Fig. 20a), only models S1N5, S2N5 and S3N5 have positive reinforcement efficiencies. The maximum reinforcement efficiency value appears in model S1N5, which is 7.0%. The worst model is S5N3 with a reinforcement efficiency value of -23.1%. Similar with the results under uniform snow load, the maximum and minimum reinforcement efficiencies under non-uniform snow load (Fig. 20b) also appear in model S1N5 and model S3N5, which are 6.4% and − 22.5%, respectively. Based on the above results, we can conclude that S1N5 is the optimal bracing reinforcement model.

For the lattice column model, the ultimate bearing capacity improvement factors under uniform and non-uniform snow loads are 80.2% and 83.4%, respectively. The steel amount increase factor is 20.3%. After calculation, the reinforcement efficiency of the lattice column model under uniform snow and non-uniform snow load is 59.9% and 63.1% respectively. Compared with the S1N5 model, the reinforcement efficiency of the lattice column model under uniform and non-uniform snow loads is about 8.6 and 9.9 times that of the S1N5 model. Therefore, under the condition that crop cultivation operation is not significantly affected, the lattice column model is preferred to improve the snow resistance ability of greenhouse.

Figure 21 shows the effect of the temporary column position on the reinforcement efficiency. Comparing Figs. 19 and 21, it can be found that the change trend of reinforcement efficiency with the temporary column position is similar to that of the ultimate bearing capacity with the temporary column position. Under uniform snow load (Fig. 21a), the reinforcement efficiency P increases firstly and then decreases at the range form HD = 0.5 m to HD = 8.0 m. As for HD = 4.5 m, the reinforcement efficiency P reaches the maximum value of 365.3%. Under non-uniform snow load (Fig. 21b), the reinforcement efficiency P also reaches its maximum value when HD = 4.5 m. The maximum reinforcement efficiency is 437.1%. Based on the above results, we can conclude that for a greenhouse with a span of 10 m, the most cost-effective position of the temporary column is 4.5 m away from the south roof end.

Conclusions

In this study, the failure mechanisms of a 10 m-span pipe-framed greenhouse under snow loads were investigated. Three reinforcement methods were proposed to improve the ability of greenhouse to resist extreme snow loads. The concept of reinforcement efficiency was proposed to evaluate the economy and effectiveness of reinforcement methods.

Compared with uniform snow loads, pipe-framed greenhouses are more sensitive to non-uniform snow loads. The main reason for the failure of pipe-framed greenhouses under non-uniform snow loads is the full-section yielding due to excessive bending moments. When the amount of steel used for flat elliptical hollow section, rectangular hollow section and hat-shaped section is the same, it is recommended to choose flat elliptical hollow section, because of its higher flexural rigidity and strong ability to resist bending moments caused by snow loads.

When the brace is installed between the south and the north roofs, it not only increases the cost but also reduces the ultimate bearing capacity. Only by adding the brace between the south roof and the column can the ultimate bearing capacity of pipe-framed greenhouses be improved. Therefore, bracing between the south and north roofs should be avoided. If bracing is required, it is recommended to install it between the south roof and the column. By substituting the lattice column for the single tube column, the lateral stiffness of the column is increased. As a result, the structural displacement is reduced and the ultimate bearing capacity is improved. Before extreme snow loads come, the ultimate bearing capacity of greenhouses can be effectively increased by setting up temporary columns on the south roof. For a greenhouse with a span of 10 m, the optimal position of the temporary column is 4.5 m away from the south roof end.

The most effective reinforcement is observed when placing a temporary column at approximately at the mid-span of the greenhouse, followed by lattice column reinforcement, and the bracing reinforcement is the smallest. However, the presence of the temporary column may interfere with cultivation operations. Therefore, it is recommended to install temporary columns only under extreme snow loads. Under normal snow loads, it is recommended to replace the single-tube column with the lattice column with higher lateral displacement stiffness.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wang, C., Nan, B., Wang, T. L., Bai, Y. K. & Li, Y. Q. Wind pressure acting on greenhouses: A review. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 14, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.25165/j.ijabe.20211402.5261 (2021).

Soriano, J., Shiguemoto, A. C. G. & Neto, J. G. V. Advances in methodologies to assess wind actions in plastic-covered greenhouses. Sci. Agr. 81 https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-992x-2022-0276 (2024).

Jeon, J., Lee, H. & Yoon, S. Optimal section design of Korean agricultural greenhouse response to climate change based on Monte Carlo simulation. Agriculture 12, 1413, https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12091413 (2022).

Maraveas, C. Wind pressure coefficients on greenhouse structures. Agriculture 10, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10050149 (2020).

Fernández-García, M. S., Rodríguez-Robles, D. & Villar-García, J. R. & Vidal-López, P. Genetic algorithm for cost optimization of different multi-tunnel greenhouse design alternatives. Agronomy 12, 2145, https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12092145 (2022).

Briassoulis, D., Dougka, G., Dimakogianni, D. & Vayas, I. Analysis of the collapse of a greenhouse with vaulted roof. Biosyst Eng. 151, 495–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2016.10.018 (2016).

Ryu, H. R., Choi, M. K., Cho, M. W., Yu, I. H. & Kim, S. Y. Damage index estimation by analysis of meteorological disasters on film plastic greenhouses. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 12, 58–63. https://doi.org/10.25165/j.ijabe.20191205.4493 (2019).

Dougka, G. & Briassoulis, D. Load carrying capacity of greenhouse covering films under wind action: Optimising the supporting systems of greenhouse films. Biosyst Eng. 192, 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2020.01.020 (2020).

Sahdev, R. K., Kumar, M. & Dhingra, A. K. A comprehensive review of greenhouse shapes and its applications. Front. Energy. 13, 427–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11708-017-0464-8 (2017).

Ha, T. et al. Finite element model updating of multi-span greenhouses based on ambient vibration measurements. Biosyst. Eng. 161, 145–156, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2017.06.019 (2017).

Lee, S., Lee, J., Jeong, Y. & Choi, W. Development of a structural analysis model for pipe structures to reflect ground conditions. Biosyst Eng. 197, 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2020.06.018 (2020).

Kang, J., Jeon, J., Yoon, S. & Choi, W. Failure conditions for stand-alone cold-frame greenhouse under snow loads. Paddy Water Environ. 17, 651–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10333-019-00691-9 (2019).

Ren, J. et al. Finite element analysis of the static properties and stability of a large-span plastic greenhouse. Comput. Electron. Agric. 165, 104957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2019.104957 (2019).

Liu, J., Wu, X., Sun, F. & Wang, B. Development and application of a crossed multi-arch greenhouse in tropical China. Agriculture 12, 2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12122164 (2022).

Hur, D. J. & Kwon, S. Fatigue analysis of greenhouse structure under wind load and self-weight. Appl. Sci. 7, 1274. https://doi.org/10.3390/app7121274 (2017).

Sim, V. & Jung, W. Wind fragility of steel and carbon-fiber reinforced plastic single-span greenhouses. J. Korean Soc. Adv. Comp. Struc. 11, 18–24. https://doi.org/10.11004/kosacs.2020.11.1.018 (2020).

Fernández-García, M. S., Vidal-López, P., Rodríguez-Robles, D., Villar-García, J. R. & Agujetas, R. Numerical simulation of multi-span greenhouse structures. Agriculture 10, 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10110499 (2020).

Kim, M. Effects of uplift resistance on continuous-pipe-foundation of single-span plastic greenhouse by steel plate pipe connector. Agriculture 12, 1988. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12121998 (2022).

Lee, J. Y. & Ryu, H. R. Structural analysis of pipe-framed greenhouses using interface elements for cross-over connections. Eng. Struct. 266, 114504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.114504 (2022).

Wang, C., Xu, Z., Jiang, Y. & Wang, T. Numerical analysis of static and dynamic characteristics of large-span pipe-framed plastic greenhouses. Biosyst Eng. 232, 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2023.06.013 (2023).

Kendirli, B. Structural analysis of greenhouses: A case study in Turkey. Build. Environ. 41, 864–871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2005.04.013 (2006).

Emekli, N. Y., Kendirli, B. & Kurunc, A. Structural analysis and functional characteristics of greenhouses in the mediterranean region of Turkey. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 9, 3131–3139. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB2010.000-3154 (2010).

Vieira Neto, J. G. & Soriano, J. Distribution of stress in greenhouses frames estimated by aerodynamic coefficients of Brazilian and European standards. Sci. Agr. 73, 97–102. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-9016-2015-0072 (2016).

Kim, R., Lee, I., Yeo, U. & Lee, S. Evaluation of various national greenhouse design standards for wind loading. Biosyst Eng. 188, 136–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2019.10.004 (2019).

Yang, C. J., Lin, M. J., Chen, P. T. & Chiu, H. L. Circular economy in practice: Building a simple greenhouse from recycled plastic. Machines 10, 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines10121207 (2022).

Tsai, M. H. & Lee, Y. C. Practical structural design and construction of an innovative composite plastic greenhouse. Agriculture 11, 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11111051 (2021).

Bai, Y., Wang, H., Wang, T. & Li, T. Design and test of new steel frame solar greenhouse. J. Shenyang Agric. Univ. 44, 542–547. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-1700.2013.05.006 (2013).

Wang, C., Jiang, Y., Bai, Y. & Wang, T. Numerical study on static properties and failure mechanisms of landing assembled Chinese solar greenhouses. Comput. Electron. Agric. 188, 106347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2021.106347 (2021).

Li, M., Wei, X., Zhao, Q. & Wang, L. Numerical simulation of structural performance in a single-tube frame for 12 m-span Chinese solar greenhouses subjected to snow loads. Agronomy 14, 1122. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14061122 (2024).

Wang, C., Wu, H., Jiang, Y., Bai, Y. & Wang, T. Stability analysis of landing assembled Chinese solar greenhouses with discrete lateral braces under snow loads. Biosyst Eng. 233, 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2023.08.004 (2023).

Li, X., Wang, C., Jiang, Y. & Bai, Y. Dynamic response analysis of a whole steel frame solar greenhouse under wind loads. Sci. Rep. 12, 5200. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-09248-z (2022).

Wang, C., Jiang, Y., Wang, T., Xu, Z. & Bai, Y. Analysis of wind-induced responses of landing assembled Chinese solar greenhouses. Biosyst Eng. 220, 214–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2022.06.003 (2022).

Wang, C., Jiang, Y., Li, X., Bai, Y. & Wang, T. Wind-induced vibration response analysis of Chinese solar greenhouses. Comput. Electron. Agric. 181, 105954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105954 (2021).

Maraveas, C. & Tsavdaridis, K. D. Strengthening techniques for greenhouses. AgriEngineering 2, 37–54. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering2010003 (2020).

Uematsu, Y. & Takahashi, K. Collapse and reinforcement of pipe-framed greenhouse under static wind loading. J. Civ. Eng. Archit. 14, 583–594. https://doi.org/10.17265/1934-7359/2020.11.001 (2020).

Uematsu, Y. & Takahashi, K. Collapse behavior of pipe-framed greenhouses with and without reinforcement under snow loading: A 3-D finite element analysis. J. Civ. Eng. Archit. 18, 51–59. https://doi.org/10.17265/1934-7359/2024.02.001 (2024).

Moriyama, H., Mears, D. R., Sase, S., Ikeguchi, A. & Yamaguchi, T. Reinforcement for pipe-framed greenhouse under snow load and design optimization considering steel mass. J. Soc. Agric. Struct. Japan. 38, 263–274. https://doi.org/10.11449/sasj1971.38.263 (2008).

Lee, S. H., Shin, K. J. & Lee, H. D. Behavior of plastic greenhouses under symmetric loading before and after strengthening with tension ties. Adv. Steel Constr. 14, 694–709. https://doi.org/10.18057/IJASC.2018.14.10 (2018).

Scarascia-Mugnozza, G., Fuina, S. & Castellano, S. Structural design and experimental tests on a model of tensegrity greenhouse prototype. J. Agric. Eng. 52 https://doi.org/10.4081/jae.2021.1189 (2021).

GB/T 51183 – 2016. Code for the Design Load of Horticultural Greenhouse Structures (China Planning Press, 2017).

Wang, C. et al. Ultimate bearing capacity of the solar greenhouse with hat-shaped steel under snow loads. Trans. CSAE. 38, 172–179. https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2022.19.019 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Effect of single tube sections on the structural safety of Chinese solar greenhouse skeletons. Sci. Rep. 11, 19307. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-98779-y (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Agricultural Major Technology Collaborative Promotion Project of Zhejiang Province, China (2023ZDXT05-03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Cong Wang: Writing—original draft preparation, formal analysis, software. Jianbo Shen: Validation, methodology, visualization. Yingchun Jiang: Conceptualization, validation, data curation. Longjing Zhu: Writing—review and editing, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Shen, J., Jiang, Y. et al. Failure mechanisms and reinforcement of pipe-framed solar greenhouses under snow loads. Sci Rep 15, 16403 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01186-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01186-w