Abstract

P-wave velocity (Vp) structures in marine areas have been estimated using marine airgun-source seismic surveys and refraction methods. The lateral resolution of Vp structures depends on the number of receivers and shots. In marine environments, Vp resolution is often limited due to the sparse distribution of ocean bottom seismometers (OBSs). Recently, distributed acoustic sensing (DAS) offers a cost-effective alternative, providing high-density strain measurements along optical fiber cables. This study demonstrates that seismic refraction using DAS data is effective for imaging shallow Vp structures with high lateral resolution. A seismic survey was conducted using R/V Hakuho-maru, airgun sources, and DAS and OBS measurements along a seafloor optical fiber cable off Sanriku, Japan. Strong lateral heterogeneities in the Vp structure were observed, due to the dense spatial sampling of DAS data. The two-dimensional Vp structure obtained from the DAS data showed good agreement with the seismic reflection profile. This experiment highlights the unique advantages of DAS data over OBSs for seismic refraction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

P-wave velocity (Vp) structures in marine areas are generally estimated using seismic refraction surveys with airgun-seismic sources, ocean-bottom seismometers (OBS), and/or hydrophone streamers. The lateral resolution of Vp structures estimated using the seismic refraction method is limited by the spacing of the receivers or seismic sources. In seismic refraction analysis, spatially dense observations have enabled improvements in the lateral resolution of the Vp structure. However, deploying a large number of OBSs is challenging due to their high costs. OBSs are typically installed at intervals of several kilometers because of these limitations. Even with a spatially dense seismic source, the resolution is determined by the receiver spacing. In contrast, hydrophone streamers have a much larger number of receivers, with spatial intervals typically just a few meters. However, using hydrophone streamer data for Vp structure estimation in seismic refraction surveys has several drawbacks. Estimating deep structures is difficult with hydrophone streamers because their length is limited1. This restriction prevents the collection of deep-penetrating seismic refraction waves, which are necessary for gathering velocity information from deeper regions. Moreover, the signal-to-noise ratio of seismic waves is generally lower because hydrophone streamers are towed near the sea surface, where noise levels are higher compared to the seafloor2.

By contrast, the spatial horizontal resolution is higher in seismic reflection surveys because the intervals between both the source and receiver can be small. Seismic reflection surveys are effective for obtaining subsurface reflectivity images, with high sensitivity to impedance contrasts in the subsurface3,4,5. The lateral resolution of seismic reflection images has reached less than ten meters. Therefore, these high-resolution images have revealed detailed lateral heterogeneity in horizontal reflectivity across various study regions4,5,6. However, accurately estimating Vp structures from seismic reflection analysis is challenging because these analyses are optimized to produce clearer reflection images3. To estimate the lateral heterogeneity of Vp structures and fully understand the subsurface properties in marine areas, improving the lateral resolution of Vp structures in seismic refraction surveys is essential.

Recently, Distributed Acoustic Sensing (DAS) technology has emerged, offering high-resolution strain or strain rate measurements (at spatial intervals of several meters) over long distances (up to tens of kilometers)7. DAS cables have a higher station density than traditional seismic observation methods using individual seismic sensors, making DAS especially useful in environments, where deploying large numbers of seismometers, such as in offshore areas, is difficult. For instance, DAS data have been used for seismic observations of natural earthquakes in marine areas8. Additionally, several pioneering studies conducted marine-airgun seismic source surveys with DAS data. From using DAS data with a marine-airgun source, an offshore S-wave velocity (Vs) structure beneath a cable was estimated by using dispersion curves of Scholte-wave9. A seismic reflection image of shallow subsurface structures was also obtained by using DAS10. Although seismic refraction surveys have not been applied to DAS data, DAS offers clear advantages over both OBS and hydrophone streamers. The receiver density along a DAS cable is significantly higher than the typical receiver density in marine airgun-source surveys using OBSs. As a result, the horizontal resolution of the Vp structure is expected to improve with the dense spatial data provided by DAS. Although the receiver density of DAS is similar to that of hydrophone streamers, DAS has an added advantage: its stations are fixed to the seafloor, allowing for the observation of seismic sources with long offset distances. Consequently, DAS data from seafloor cables are well-suited for seismic refraction surveys with airgun sources, enabling the acquisition of detailed Vp structures with high resolution in both the vertical and horizontal directions.

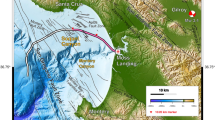

This study conducted seismic refraction surveys using a marine airgun-seismic source and DAS measurements to estimate shallow Vp structures with high lateral resolution. The overview of data processing employed in this study is available in the supplemental file (Fig. S1). Data were collected from DAS measurements connected to a seafloor cable, along with OBS data, off the coast of Sanriku, Japan (Fig. 1). A common receiver gather (CRG) of the DAS data was obtained after processing. The seismic signals of refracted, reflected, and direct water waves from the airgun source were identified in the CRG records. These records were converted from the T (time)–X (distance) domain to the τ (intercept time)–p (slowness) domain using the slant stack11 method, with a spatial interval of 125 m. Analytical methods for seismic refraction, such as τ-sum inversion, are often used to estimate shallow Vp structures11,12. The τ-sum inversion method estimates the one-dimensional (1-D) Vp structure beneath a receiver or source. An analysis of the τ–p domain has advantages over that of the T–X domain for shallow Vp structures because the travel time of refracted P-waves from shallow layers is generally longer than that of direct water waves from a seismic source in marine refraction surveys. Another advantage of analysis in the τ-p domain is the high vertical resolution of the obtained shallow seismic structures12. The dense DAS measurements allowed us to observe gradual and/or sudden spatial changes in the trajectories of refracted P-waves in the τ-p domain. This high-density data enabled us to trace spatial changes in P-wave trajectories. The τ-sum inversion method was applied to determine 1-D Vp structures below each observation point at distances from 20 km to 85 km from the coast. By aligning the 1-D velocity structures, a high-resolution two-dimensional (2-D) Vp structure was constructed. The resulting 2-D Vp structure revealed three distinct units with different vertical gradients of Vp. Detailed lateral heterogeneities in Vp, as well as variations in the thickness of each unit, were also identified. The 2-D Vp structure obtained from the DAS data showed good agreement with the seismic reflection profile. In conclusion, our study demonstrated that spatially dense DAS data significantly enhanced the lateral resolution of Vp structures in seismic refraction surveys. This experiment highlights the unique advantages of DAS data over OBSs.

Location of the seismic experiment described in this study. The black line represents the route of the seafloor cable installed by the Earthquake Research Institute, University of Tokyo. The blue line marks the segment where DAS data was recorded, covering a total length of 100 km. The red line indicates the seismic refraction and reflection profile from this study. The green line shows the along-profile shooting range of approximately 200 km, where 1,500 LL airguns were fired at 40 second intervals, every 100 m. The purple triangles mark the positions of pop-up type OBSs used in the analysis, while white triangles indicate OBSs not used for analysis. The purple square (SOB3) and white squares (SOB2 and SOB3) represent in-line OBSs connected to the seafloor cable system. Only the SOB3 data was used to estimate the Vp structure. The image was created by the author using the Generic Mapping Tools, Version 6.3.0 (https://www.generic-mapping-tools.org/team.html).

Result

The CRG records of the DAS data in the T-X domain clearly showed water, refraction, and reflection waves from the airgun at distances of 20–60 km from the coast (Top panels in Figs. 2-A–C). The direct water waves were recognized as the first arrivals at offset distances of up to 5 km (Fig. 2). Following the direct water waves, refraction waves with slow apparent velocities (1.5–2.5 km/s) were observed. At offset distances from 3 km to 15 km, the first arrivals of refracted waves with faster apparent velocities (3.0–5.0 km/s) were identified (Fig. 2). By comparing the CRG records of the vertical component data from the pop-up OBS installed along the cable (Fig. 1), these refracted waves were interpreted as penetrating P-waves (Fig. S2). The refracted waves recorded by the OBS had the same apparent velocities as those recorded by the DAS measurements. Furthermore, the travel times in the OBS records were consistent with those in the DAS records (Fig. S2).

Four examples of CRG records in the T-X domain and τ-p domain. (A), (B), (C), and (D) indicate the profiles at stations No. 5228 (26.0 km), No. 8135 (40.0 km), No. 10,226 (50.0 km) and No. 14,306 (70.2 km), respectively. Fifty-one adjacent DAS stations were collected and displayed, aligned by offset distance in the CRGs in the T-X domain (Top panels). A bandpass filter from 8 Hz to 15 Hz was applied to each trace in the CRG records. Each trace was normalized by its amplitude, and all travel times were reduced by 3.5 km/s. Within a distance of 5 km, the refracted P-wave can be identified following the arrival of the direct water wave. At distances between 5 km and 15 km, the refracted P-wave is clearly seen as the first arrival. Transformation of CRG data from the T-X domain to the τ-p domain was performed separately for westward and eastward shooting from the receiver. Panels of the left and right bottom in each figure display the τ-p domain for westward and eastward shooting, respectively. Black arrows indicate the trajectories of refracted waves in the τ-p domain.

Refracted waves could not be clearly identified in the CRG records of the DAS at distances greater than 60 km from the coast (Fig. 2-D). There are several reasons for the low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of seismic signals in offshore DAS data: the attenuation of laser light over long travel distances in DAS observations, the design of commercial fibers to minimize back-scattering, the poor coupling between fiber and cable to protect the fiber, and the negligible consideration of cable-to-ground or cable-to-water coupling during deployment7,8.

Using a slant stack (Methods), we transformed CRG data from the T-X to the τ-p domain. DAS strain data was processed separately for eastward and westward shots, with offsets limited to 15 km. Stacking techniques, including slant stacks for DAS data, effectively improve the SNR of seismic signals. The very short receiver intervals in DAS measurements, which are shorter than the wavelength of the P-wave, allow us to stack a large amount of data without spatial aliasing. Assuming a Vp of 1.5 km/s and a frequency of 11.5 Hz (the central frequency of the 8–15 Hz bandpass filter), a P-wave wavelength is estimated to be approximately greater than 130 m. Therefore, data were gathered from 51 adjacent DAS stations (in the distance range of approximately 125 m) before the τ-p transformation and transformed this gathered DAS data from the T-X domain into the τ-p domain (hereafter referred to as “gathered τ-p transformation”). Since the gathered τ-p transformation enhanced the P-wave refraction arrivals, the trajectory of the refracted P-waves can be clearly seen in the τ-p domain (Fig. 2). When the τ-p transformation was applied to the CRG data from only one DAS station at a distance of 76.7 km from the coast, it was difficult to identify the trajectory of P-wave refraction (Figs. 3-A and C). In contrast, the trajectories of the refracted P-waves can be clearly obtained using the gathered τ-p transformations (Figs. 2 and 3-B and D). In particular, the improvement in the SNR of the seismic signal by the gathered τ-p transformation is effective for data in offshore areas more than approximately 60 km from the coast (Fig. 3) because the decrease in SNR due to laser light attenuation was more significant in offshore areas than in nearshore areas.

Comparison of τ-p domain data converted from gathered data from adjacent 51 DAS stations in the T-X domain (B and D) with data from a single DAS station (A and C). (A) and (B) show the τ-p domain data for eastward shooting from a DAS station. (C) and (D) show the τ-p domain data for westward shooting. The gathered data in the τ-p domain has a better signal-to-noise ratio for refracted P-waves, making their trajectories clearer in (B) and (D).

The shapes of the trajectories for the refracted P-wave in the τ-p domain are related to the Vp structure beneath each receiver. The spatially dense dataset from DAS measurements offers a new opportunity to observe spatial changes in the shapes of the trajectories for refracted P-waves in the τ-p domain (Figs. 4A and B). For example, intercept times on trajectories at velocities of 2.0 km/s (i.e., p of 0.5 s/km) and 3.2 km/s (i.e., p of 0.3125 s/km) change gradually and suddenly at different distances from the coast, respectively. The intercept times at a velocity of 2.0 km/s along the trajectories at each receiver gradually increased seawards, with a horizontal gradient of approximately 0.018 s/km (Fig. 4C). In contrast, the increase in τ at a velocity of 3.2 km/s with distance from the coast was not monotonic. At distances ranging from 25 km to 45 km, τ gradually increased from 0.6 s to 1.6 s. However, τ suddenly increased from 1.6 s to 2.4 s within the distance range of 45 to 55 km. Beyond 55 km, τ gradually increased from 2.4 s to 2.6 s. These sudden spatial changes in τ at each velocity suggest lateral heterogeneity in the Vp structures.

Spatial changes in the trajectories of refracted P-waves for westward shooting (A) and eastward shooting (B) from a receiver in the τ-p domain. The numbers in the upper left of (A) and (B) indicate distances from the coast. Small black arrows denote the trajectories of refracted waves in the τ-p domain. (C) shows the spatial changes in intercept time for westward (left) and eastward (right) data. Blue and red circles in (C) mark intercept times at velocities of 2.0 km/s and 3.2 km/s, respectively. Spatially dense DAS measurements provide new opportunities to observe gradual and sudden changes in the shape of P-wave trajectories in the τ-p domain.

Estimation of the 1-D Vp structure using the τ-sum inversion with an ultra-short horizontal interval (approximately 125 m in this study) was conducted using the spatially dense DAS data. Moreover, the vertical gradient of Vp was calculated for each 1-D profile. Two 1-D Vp structures and the vertical gradient of Vp below a single observation point were obtained through the τ-sum inversion using the τ-p data from the east side and the west side of a linear profile of airgun sources passing through the observation point. Based on the advantages of the spatially dense DAS data, a 2-D Vp structure was obtained by aligning 1-D profiles from both the east and west sides at an ultra-short interval. No smoothing for the horizontal direction was applied. The horizontal position of each Vp, the vertical gradient of Vp, and depth as discrete points are defined by Eq. (2) in the Methods section, resulting in a 2-D Vp structure obtained at distances between 25 and 85 km from the coast, with seafloor depths ranging from 0.3 to 1.8 km. (Figs. 5A and B). Using the 2-D profile of the Vp vertical gradient, the obtained 2-D Vp structure was divided into three units with different vertical gradients (Fig. 5B). The vertical Vp gradients changed at Vp of 2.0 km/s and 3.5 km/s. The spatial averages of Vp and its vertical gradient for the uppermost unit (unit-1) are 1.79 km/s and 0.03 s−1, respectively. The unit underlying unit-1 (unit-2) has a spatial average Vp of 2.62 km/s and a vertical gradient of 0.07 s−1. For unit-3, the spatial Vp and its vertical gradient are 4.27 km/s and 0.45 s−1, respectively.

(A) Two-dimensional Vp structure estimated using the τ-sum inversion method. (B) Same as (A), but black lines indicate gaps in the vertical Vp gradient from each 1-D velocity structure. Vertical Vp gradients change at Vp values of 2.0 km/s and 3.5 km/s. Gray lines show the result of polynomial curve fitting to the gaps in the vertical Vp gradient from each 1-D structure, with the blue-filled region indicating a 95% confidence interval for the fitting. (C) Profile of the vertical gradient of Vp with depth. The 2-D Vp structure is divided into three units with different vertical gradients of Vp. (D) and (E) are similar to (A), but focus on the Vp structures of unit-1 and unit-2, respectively. To analyze the spatial changes in the Vp structures of unit-1 and unit-2, the Vp scale in (D) and (E) differs from that in (A).

The τ-sum inversion using DAS data with a short horizontal interval revealed remarkable features of spatial variation in the thicknesses of unit-1 and unit-2. The thickness of unit-1 was 0.25 km at a horizontal distance of 25 km from the coast with seafloor depth of 0.3 km and gradually increased seaward (Fig. 5B), reaching 1.2 km at a horizontal distance of 85 km from the coast with seafloor depth of 1.8 km. Although the thickness of unit-1 increases gradually with distance from the coast to offshore, the thickness of unit-2 varies over short horizontal distances. Unit-2 has a uniform thickness of 0.50 km at distances of 25–48 km from the coast and seafloor depths of 0.3–1.0 km, respectively. However, the thickness of unit-2 rapidly increases from 0.5 km to 1.5 km between distances of 48 km and 50 km. The thickness of unit-2 becomes constant again at horizontal distances greater than 50 km with seafloor depths ranging from 1.0 to 1.8 km. The τ-sum inversion with DAS data revealed significant spatial variation in the thickness of unit-2 within a horizontal distance of 5 km.

The Vp of the uppermost region of unit-1 at a distance of 20–45 km ranges from 1.65 to 1.80 km/s (Fig. 5D). The Vp values in the lowermost regions of unit-1 became approximately 1.9 km/s. The depths of the seafloor were approximately 0.6 km at a distance of 25 km, gradually increasing to approximately 0.8 km at a distance of 45 km. The thicknesses of the uppermost region of unit-1 were 0.4 km and 0.6 km at horizontal distances of 25 km and 45 km, respectively. The thickness of these regions increased monotonically (Fig. 5D). In contrast, the Vp of the uppermost region of unit-1 at horizontal distances of 45–85 km was slower than 1.65 km/s. Below this uppermost region, the Vp values gradually increased from 1.65 km/s to 1.9 km/s (Fig. 5D). The depths of the seafloor gradually increased from 0.8 km to 1.6 km at distances ranging from 45 km to 85 km. The thicknesses of the uppermost regions were 0.6 km, 0.4 km, and 1.0 km at distances of 45 km, 60 km, and 85 km, respectively, with thicknesses gradually varying. In unit-2, the uppermost regions at horizontal distances of 25–85 km have a Vp of approximately 2.2 km/s (Fig. 5E). The Vp of the bottom layer of unit-2 became approximately 3.2 km/s. The thicknesses at horizontal distances of 25–50 km ranged from 0.4 to 0.6 km. At distances of 50–85 km, the thickness of unit-2 is approximately 1.4 km. The layers with a Vp of 2.6–2.8 km/s at distances ranging from 55 to 85 km have thicknesses of approximately 0.8 km. In contrast, the thicknesses of the layer with Vp of 2.6–2.8 km/s at distances ranging from 25 to 55 km can be recognized as smaller than 0.1 km. Due to the spatial density of the DAS data, spatial variation in the thickness of the layers can be obtained sequentially. Additionally, sudden spatial changes in the structures of unit-1 at a distance of 45 km and unit-2 at a distance of 50 km can be clearly recognized. The 2-D Vp structures, obtained with a spatial interval of 125 m through τ-sum inversion with DAS data, revealed lateral heterogeneity with a horizontal resolution of a few kilometers in the Vp structure.

Discussion

In estimating the Vp structure by τ-sum inversion, evaluating the horizontal resolution of the 2-D Vp model is difficult because CRG data were used in the T-X domain with offsets smaller than 15 km for the τ-p transformation. We estimated 1-D Vp structure at an interval of 125 m under the assumption that the velocity structure over a distance of 15 km is interpreted as a 1-D structure. Therefore, the velocity structures for adjacent intervals are ideally different. In other words, we obtained a moving-average-structure at every 125 m using a distance window of 15 km. Indeed, there is difficulty to evaluate directly a horizontal resolution of estimated structures because of a long-distance window. In contrast, the horizontal resolution of seismic reflection images is high. It is well known that the horizontal resolution of high-resolution seismic reflection images, particularly when using a single-channel streamer, can reach a few tens of meters. Comparing the lateral variation of the velocity discontinuities in the Vp model with the horizontal reflectors in a seismic reflection profile obtained using a single-channel streamer is effective for evaluating the lateral resolution of the 2-D Vp model. Therefore, our 2-D Vp structure was compared with the seismic reflection profile obtained using a single-channel hydrophone streamer (see Methods). The depths to two-way travel times used in this 2-D velocity model were converted and compared with the seismic reflection profile.

Figure 6A shows the continuous lateral reflectors in the seismic reflection profile. Several continuous lateral reflectors were observed over a distance range of 25–85 km (Fig. 6A and B). The interfaces of unit-1, unit-2, and unit-3 corresponded to the interpretation of lateral continuous reflectors (lines A and B in Figs. 6A and B). In unit-1, several lateral continuous reflectors can be seen at distances of 45–80 km (Fig. 6C). The lateral continuous reflectors and iso-velocity curves for the two-way travel times showed good consistency. At distances of 48 km and 66 km, the two-way travel times of the lateral continuous reflectors rapidly increased (areas A and B in Figs. 6C and D). In these regions, the layer with a Vp slower than 1.65 km/s became suddenly thicker. From the comparison between the seismic reflection image and our 2-D Vp structure, the velocity variation in unit-1 is consistent with the shape of the reflectors in the reflection profile (Fig. 6B). The 2-D Vp structure obtained by the τ-p method using DAS data can express lateral heterogeneities of less than a few kilometers (Fig. 6). Consequently, it can be concluded that the lateral resolution of the 2-D Vp structure was higher than a few kilometers. It is known that the velocity profile obtained by the τ-p method has a high spatial resolution in the vertical direction11. The 2-D Vp structure obtained by the method proposed in this study has high resolution in both vertical and horizontal directions, comparable to the reflection profiles obtained by airgun sources and hydrophone streamers.

(A) Seismic reflection profile obtained from SCS data. (B) Same as (A), but gray, blue, green, and orange lines highlight laterally continuous reflectors. (C) Two-dimensional Vp structure in two-way travel time. (D) Two-way travel time range corresponding only to unit-1. (E) 2-D Vp structure of unit-1 obtained by τ-sum inversion. In (B–E), the blue and green lines show the interface between unit-1 and unit-2 (Line A) and unit-2 and unit-3 (Line B), respectively. The orange line indicates a laterally continuous reflector from the seafloor multiple. In regions A and B in (C) and (D), two-way travel times of the continuous reflectors increase rapidly, and the layer with a Vp slower than 1.65 km/s thickens abruptly in two-way travel times. The vertical axis represents two-way travel time from the sea surface.

Before DAS technology became available, the τ-p method of estimating a 1-D Vp structure mainly used data from OBSs. Since OBSs were usually installed sparely at intervals of several kilometers. Therefore, detailed lateral variations in the Vp structures using data from conventional OBS surveys with marine-airgun sources could not be estimated. In contrast, the DAS measurement obtains seismic data from controlled airgun sources at short intervals over a long distance. Spatially dense data from DAS measurement enables us to estimate a 1-D Vp structure at every tens or hundreds of meters by the τ-p method. This means that lateral heterogeneities of the velocity structure can be estimated (Fig. 5). Since the trajectory of refracted P-wave arrivals in the τ-p domain was identified at every 125 m, Vp structures from the seafloor to a depth of 5 km can be obtained every 125 m in the horizontal direction through the τ-sum inversion using DAS data. The 2-D Vp structure was obtained using the τ-sum inversion for the DAS data. Three velocity units with lateral heterogeneities with a horizontal resolution of a few km were revealed by spatially dense DAS data (Fig. 5).

Although seismic reflection surveys using hydrophone streamers provide seismic reflection images with high lateral resolution (several tens of meters)4, obtaining a precise Vp structure using seismic reflection methods is challenging, especially in deep regions. The lateral resolution of the Vp structure from conventional seismic refraction surveys using pop-up OBSs is much smaller than seismic reflection images, although precise Vp can be estimated using seismic refraction methods. In contrast, our new approach for estimating seismic structures using DAS data enabled us to obtain precise Vp structures with high resolution in both vertical and horizontal directions.

The ratio of P- and S-wave velocities (Vp/Vs) is essential for estimating pore fluid pressure and rock properties such as porosity13,14,15. This information on pore fluid pressure or porosity aids in understanding fault properties16,17,18 and monitoring subsurface oil or CO2 reservoirs19,20. In recent years, several studies have applied ambient noise surface wave analysis to seafloor DAS data, estimating Vs structures with a lateral resolution of hundreds of meters21,22,23. While the analysis using ambient noise surface waves provides the Vs structure, our method additionally provides another physical property, the Vp structure. Combining the Vp and Vs structures allows for the estimation of the Vp/Vs structure in a marine area at a spatial interval of hundreds of meters. The long-term observation using DAS measurement generally has no difficulty because seafloor optical fiber cables are generally deployed for the long term. A simple connection of an interrogator unit to the end of the fiber allows repeated monitoring at a low cost. The monitoring of P- and S-wave velocities can be performed by applying our method and surface wave analysis repeatedly for the long term. A long-term monitoring of Vp/Vs can reveal variations in pore fluid pressure, saturation, or fracturing within the subsurface, and gives useful indicators for dynamic processes occurring in reservoirs or fault zones. The long-term monitoring with low cost will give important information for both scientific and engineering fields.

Seismic refraction survey with DAS also has several disadvantages compared to that with OBSs for the τ-sum inversion method although DAS technology offers significant benefits for seismic refraction surveys, particularly in terms of enhancing lateral resolution of Vp images. For example, the noise level of DAS data is generally higher than that of OBS data (Figs. 2 and 3, and S2). We encounter competition between the quality of data at a single station and the spatial density of data with noise. In the case that SNRs of DAS data are low, it is difficult to identify the trajectory of refracted P-wave exactly in the τ–p domain (Fig. 3-A and -B). Without picking up an obvious trajectory, accurate Vp cannot be estimated by the τ-sum inversion. Although a spatial sampling of DAS observation is denser than that of OBS observation, OBS records generally have high SNR. Trajectories for P-wave refraction waves are identified easily in the τ–p domain (Fig. S2). Therefore, processing using OBS records with high SNR is sometimes superior to that using DAS data with a spatial density of DAS. Additionally, while an OBS usually has three-component seismometers, DAS can measure one-component strain (or strain-rate) parallel to a fiber. Because axial strain represents the spatial derivative of displacement along the cable, DAS is more sensitive to seismic waves with lower apparent velocities than to those with higher apparent velocities24. It is indispensable to observe the trajectory of refracted P-waves with high apparent velocity from deep region layers τ–p domain clearly for estimation of Vp structure in deep regions. Moreover, DAS has the highest sensitivity to P-waves propagated along a fiber. On the other hand, P-waves incident vertically to a fiber lay on the seafloor have difficulty to be detected by DAS measurement. Because refracted P-waves from deep regions arriving on the seafloor have small incident angles, DAS observation using a seafloor cable is not so suitable for the estimation of velocities in a deep region. To resolve these disadvantages of DAS measurement, several processing techniques have been proposed, such as noise reduction methods25 and strain-to-displacement conversion methods26. The novel processing methods of DAS data should be useful for estimating deep structures by seismic refraction surveys with DAS.

Conclusion

A seismic survey was conducted off Sanriku, Japan, using airgun sources, DAS, and OBSs in 2020. By applying τ-sum inversion to DAS data, we successfully obtained high-resolution 1-D Vp profiles every 125 m along the cable. Although the τ-sum inversion enables us to estimate a Vp structure in shallow parts just below a station with high resolution for a depth direction, a sampling interval of a spatially horizontal distance coincides with an interval of stations. Therefore, the distribution of Vp profiles for horizontal direction becomes sparse for a conventional OBS experiment. On the other hand, a dense horizontal distribution of the Vp profiles is achieved using DAS data due to ultra-high density of receivers. In this study, we obtained 1-D Vp profiles with an interval of a few hundred meters. By applying the τ-sum inversion method to DAS data, numerous Vp structures which have a high resolution for depth direction can be obtained along the cable with a short distance. Therefore, a 2-D Vp structure was constructed by aligning these 1-D Vp structures. The obtained 2-D Vp structure revealed strong lateral heterogeneities in Vp and layer thicknesses and was consistent with the seismic reflection profile along the cable. It becomes obvious that a seismic refraction survey using DAS measurement has the advantage of resolving a fine-scale subsurface velocity structure. Our study highlighted the potential of DAS data, which improved imaging of Vp structure in offshore regions. The capability of DAS data to estimate high-resolution Vp structures contributes to research in various fields.

Methods

Seismic data acquisition

In 1996, the Earthquake Research Institute of the University of Tokyo installed a seafloor seismic and tsunami observation system (Sanriku cable system) that used an optical fiber cable to transmit geophysical data offshore Sanriku (Fig. 1). This seafloor cable system has three seismic stations (SOB1-3), with spare fibers (dark fibers) available for DAS observations. The three seismic stations were equipped with accelerometers, collecting acceleration data at a sampling frequency of 100 Hz in real-time.

A seismic survey was conducted using airgun seismic sources: DAS and OBSs (Fig. 1)27. The survey took place from November 3 to November 8, 2020. The Hakuho-maru R/V, belonging to the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), utilized four large airguns (Bolt 1500 LL) as airgun seismic sources. Each airgun had a chamber capacity of 1,500 in³ and was shot along a profile of approximately 200 km. The shooting interval was 40 s, corresponding to a distance of about 100 m. A short hydrophone streamer with two channels was used to acquire the reflection data, resulting in seismic reflection records of 15 s in length with a sampling frequency of 1 kHz.

DAS measurements using the Sanriku cable system were performed with two identical DAS interrogators made by AP Sensing GmBH28. Strain data along the cable were recorded at a temporal sampling frequency of 500 Hz. The sensing range, spatial sampling interval, and gauge length were set to 100 km, 5 m, and 40 m, respectively. In addition to the DAS and cabled seismic stations, nine free-fall pop-up OBSs were deployed along the seafloor cables (Fig. 1). The pop-up OBSs were installed before the shooting of the airguns and recovered after the shooting was completed. In this study, the pop-up OBSs and SOB within the range of DAS observations were used to evaluate the effectiveness of applying the seismic refraction method to DAS data. Thus, data from the four pop-up OBSs and SOB3 were utilized. The pop-up OBSs employed in this study have a three-component velocity-sensitive sensor with a natural frequency of 4.5 Hz. Although the sampling frequency of the data from the pop-up OBSs was 200 Hz, it was set to 50 Hz to unify the sampling frequencies for all datasets.

CRG data were created from the DAS and OBS data. The time window started 5 s before the shot time, and the duration was set to 35 s. The seafloor positions of all DAS stations and OBSs were estimated from the travel times of the direct water waves from the airguns. The DAS stations were positioned every 100 stations, approximately 500 m apart. Positioning errors are estimated at tens of meters. The seafloor positions of the DAS stations between the station positions determined by the airguns were estimated using linear interpolation.

τ-sum inversion

The CRG data were transformed in the T-X domain into τ-p domain data to obtain the Vp structure of the shallow layers. The slant stacking technique11,12 transforms seismic data in the T-X domain into the τ-p domain. The τ-sum inversion using discretely sampled τ-p data can be performed when seismic sources are positioned at the sea surface and receivers are located on the seafloor as follows12:

where \(\:{h}_{0}\) and \(\:{c}_{0}\) are the thickness of the seawater layer and Vp in seawater, respectively. The value of \(\:{c}_{0}\) was set to 1.5 km/s. \(\:{h}_{i}\) and \(\:{p}_{i}\) are the thickness and slowness of the P-wave in the ith layer, respectively. The mathematical derivations of Eq. (1) can be found in the supplemental file.

The dominant frequency of the airgun source (large capacity airgun, Bolt 1500LL) is approximately 5 Hz (Fig. S3). We utilized a higher frequency band (8–15 Hz) to enhance spatial resolution. It is known that a large capacity airgun radiates sufficient energy in this frequency band. Therefore, a bandpass filter was applied to all CRG data from the DAS and OBSs in the frequency range of 8–15 Hz. The CRG data were transformed from the T-X domain to the τ-p domain for eastward and westward shooting from the receiver, respectively. Data with offsets smaller than 15 km were used for the transformation. For a straight fiber cable laid horizontally, the DAS measurement closely approximates that of a linear strain meter7. Therefore, the horizontally axial strain (i.e., the DAS data) has low sensitivity to vertically incident P-waves29. To increase the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of P-waves, data from 51 adjacent DAS stations were gathered and transformed into CRG data, making the T-X domain into the τ-p domain.

The data mapped into the τ-p domain clearly showed the trajectories of refracted P-waves from the shallow layers for both DAS data (Fig. 2) and the vertical component data of the OBS (Fig. S2). The trajectories of the refracted waves were manually selected, and the τ-sum inversion was performed. One-dimensional Vp structures were obtained at spatial intervals of approximately 125 m. Additionally, the vertical gradient of Vp was calculated for each 1-D profile. The analysis range was from 25 km to 80 km from the coast. Assuming a laterally homogeneous medium, the ray parameter measured by the slant stack technique (i.e., p) reflects the velocity in the horizontal direction at the deepest point of a seismic ray. The offset distance between the receiver and the deepest point on the ray path is described as follows:

where, τ and p are intercept time and slowness, respectively, and xb is the offset distance between the receiver and the deepest point on the ray path. The mathematical derivation of Eq. (2) is provided in the supplementary file. Velocity-depth and vertical Vp gradient-depth profiles from the τ-sum inversion methods have already been obtained. From this equation and the obtained profile, the horizontal offset from the receiver at a given depth can be calculated. In other words, the velocities, vertical gradients, and depths were plotted in two dimensions. Consequently, a 2-D Vp structure and a 2-D vertical Vp gradient profile were obtained at offsets between 25 km and 80 km from the coast (Fig. 5). Using the 2-D profile of the Vp vertical gradient, the obtained 2-D Vp structure was divided into three units with different vertical Vp gradients. The vertical Vp gradients changed at Vp values of 2.0 km/s and 3.5 km/s. Polynomial curve fitting was applied to the interface data points of each 1-D velocity structure. The degree of the polynomial curve was determined by minimizing the Akaike Information Criterion. The degrees for the interfaces between unit-1 and unit-2, and unit-2 and unit-3 were 7 and 9, respectively.

Seismic reflection image

The seismic reflection profile was obtained using single-channel seismic (SCS) data (Fig. 6-A). Additionally, the prediction error filtering method with a maximum lag time of 0.1 s to remove repeated signals and a bandpass filter between 20 Hz and 40 Hz to the seismic data, were applied. Automatic gain control with a time-gate length of 1.5 s was also utilized.

Data Availability

The DAS observations were conducted as part of the Earthquake and Volcano Hazards Observation and Research Program (Earthquake and Volcano Hazard Reduction Research) by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code Availability

The codes used in this study are available upon request from the authors.

Data Availability

The DAS observations were conducted as part of the Earthquake and Volcano Hazards Observation and Research Program (Earthquake and Volcano Hazard Reduction Research) by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Jamali Hondori, E., Guo, C., Mikada, H. & Park, J. O. Full-Waveform inversion for imaging faulted structures: A case study from the Japan trench forearc slope. Pure Appl. Geophys. 178, 1609–1630 (2021).

Jones, E. J. W. Marine Geophysics (Wiley, 1999).

Kamei, R., Pratt, R. G. & Tsuji, T. Waveform tomography imaging of a megasplay fault system in the seismogenic Nankai subduction zone. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 317–318, 343–353 (2012).

Fujie, G. et al. The nature of the Pacific plate as subduction inputs to the Northeastern Japan Arc and its implication for subduction zone processes. Prog Earth Planet. Sci. 10, 1–28 (2023).

Tsuru, T. et al. Tectonic features of the Japan trench convergent margin off Sanriku, Northeastern Japan, revealed by multichannel seismic reflection data. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 16403–16413 (2000).

Park, J. O., Tsuru, T., Kodaira, S., Cummins, P. R. & Kaneda, Y. Splay fault branching along the Nankai subduction zone. Science 297, 1157–1160 (2002).

Zhan, Z. Distributed acoustic sensing turns Fiber-Optic cables into sensitive seismic antennas. Seismol. Res. Lett. 91, 1–15 (2020).

Shinohara, M. et al. Distributed Acoustic Sensing measurement by using seafloor optical fiber cable system off Sanriku for seismic observation. OCEANS 2019 MTS/IEEE SEATTLE Preprint at (2019).

Trafford, A. et al. Distributed acoustic sensing for active offshore shear wave profiling. Sci. Rep. 12, 9691 (2022).

Taweesintananon, K., Landrø, M., Brenne, J. K. & Haukanes, A. Distributed acoustic sensing for near-surface imaging using submarine telecommunication cable: A case study in the Trondheimsfjord, Norway. Geophysics 86, B303–B320 (2021).

Stoffa, P. L., Buhl, P., Diebold, J. B. & Wenzel, F. Direct mapping of seismic data to the domain of intercept time and ray parameter; a plane-wave decomposition. Geophysics 46, 255–267 (1981).

Shinohara, M., Hirata, N. & Takahashi, N. High resolution velocity analysis of ocean bottom seismometer data by the τ-p method. Mar. Geophys. Res. 16, 185–199 (1994).

Dvorkin, J., Mavko, G. & Nur, A. Overpressure detection from compressional- and shear-wave data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 3417–3420 (1999).

Akuhara, T., Tsuji, T. & Tonegawa, T. Overpressured underthrust sediment in the Nankai trough forearc inferred from transdimensional inversion of high-frequency teleseismic waveforms. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088280 (2020).

Buckingham, M. J. Compressional and shear wave properties of marine sediments: comparisons between theory and data. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 117, 137–152 (2005).

Tsuji, T. et al. VP/VS ratio and shear-wave splitting in the Nankai trough seismogenic zone: insights into effective stress, pore pressure, and sediment consolidation. Geophysics 76, WA71–WA82 (2011).

Takemura, S. et al. A review of shallow slow earthquakes along the Nankai trough. Earth Planet Space. 75, 164 (2023).

Scholz, C. H. Earthquakes and friction laws. Nature 391, 37–42 (1998).

Ajayi, T., Gomes, J. S. & Bera, A. A review of CO2 storage in geological formations emphasizing modeling, monitoring and capacity Estimation approaches. Pet. Sci. 16, 1028–1063 (2019).

Medina, C. R., Mastalerz, M. & Rupp, J. A. Characterization of porosity and pore-size distribution using multiple analytical tools: implications for carbonate reservoir characterization in geologic storage of CO2. Environ. Geosci. 24, 51–72 (2017).

Fukushima, S. et al. Detailed S-wave velocity structure of sediment and crust off Sanriku, Japan by a new analysis method for distributed acoustic sensing data using a seafloor cable and seismic interferometry. Earth Planet Space. 74, 1–11 (2022).

Spica, Z. J. et al. Marine sediment characterized by ocean-bottom fiber-optic seismology. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088360 (2020).

Viens, L. et al. Understanding surface wave modal content for high-resolution imaging of submarine sediments with distributed acoustic sensing. Geophys. J. Int. 232, 1668–1683 (2022).

Martin, E. R., Lindsey, N. J., Ajo-Franklin, J. B. & Biondi, B. L. Introduction to interferometry of Fiber-Optic strain measurements. Distrib. Acoust. Sens. Geophys. 111–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119521808.ch9 (2021). American Geophysical Union (AGU).

Huang, T. et al. Multiple noise reduction for distributed acoustic sensing data processing through densely connected residual convolutional networks. J. Appl. Geophy. 228, 105464 (2024).

Trabattoni, A. et al. From strain to displacement: using deformation to enhance distributed acoustic sensing applications. Geophys. J. Int. 235, 2372–2384 (2023).

Shinohara, M., Yamada, T., Akuhara, T., Mochizuki, K. & Sakai, S. Performance of seismic observation by distributed acoustic sensing technology using a seafloor cable off Sanriku, Japan. Front. Mar. Sci. 9, 844506 (2022).

Cedilnik, G., Lees, G., Schmidt, P., Herstrøm, S. & Geisler, T. Ultra-long reach fiber distributed acoustic sensing for power cable monitoring. in Proceedings of the JICABLE’19 10th International Conference on Power Insulated Cables, Versailles, France (2019).

Benioff, H. A linear strain seismograph. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 25, 283–309 (1935).

Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9, 90–95 (2007).

Wessel, P. et al. The generic mapping tools version 6. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 20, 5556–5564 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs. M. Masuda, S. Tanaka, Messrs. T. Hashimoto, K. Miyakawa, and T. Yagi of the Earthquake Research Institute, University of Tokyo, for their technical support with the DAS observations. We thank the captains, ship crew, and onboard technicians of the R/V Hakuho-maru for their dedicated efforts in data acquisition during the KH20-11 cruises. Comments by Prof. N. Hirata, Prof. K. Mochizuki and Dr. Akiko Takeo inspired our research. This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan under the Earthquake and Volcano Hazards Observation and Research Program (Earthquake and Volcano Hazard Reduction Research). A part of this study was funded by the Earthquake Research Institute at the University of Tokyo. This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number 24 K22892). Some figures were created using Matplotlib30 and Generic Mapping Tools31.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SF played a leading role in this study, including data processing, analysis, and completion of the manuscript. MS contributed to the development of the analytical method and interpretation of the results. HT contributed to the estimation of the seafloor positions at all DAS stations. MS, TY, RH, RA, YI, and YY led the temporal DAS observations and interpreted the results. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fukushima, S., Shinohara, M., Yamada, T. et al. Enhanced P-wave velocity imaging by marine airgun-source seismic surveys with distributed acoustic sensing. Sci Rep 15, 18111 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01190-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01190-0