Abstract

This paper aims to assess population-based trends and distributional characteristics in the sit-ups performance, body height, body mass and body mass index (BMI) among school-aged girls in urban China from 1985 to 2019. Height, mass, BMI and sit-ups performance data for Han Chinese urban girls aged 7–18 years were obtained from the Chinese National Surveillance on Students’ Constitution and Health surveys from 1985 to 2019. Population-based trends were estimated by a post-stratification population weighting procedure. There was a moderate improvement in sit-ups performance from 1985 to 2019, increasing by 25.7% or 0.69 effect size (ES). Girls aged 10–12 years experienced the smallest improvement (0.46 ES) and girls aged 16–18 years experienced the largest improvement (0.88 ES). Improvements in sit-ups performance were the major trend across periods, but there was a negligible improvement in the 1990s (0.04 ES) and a small decrease in the 2000s (-0.36 ES), while height, mass and BMI (from 2000 to 2019) continued to increase from 1985 to 2019. The distribution of the change in sit-ups performance was uneven, the improvements were somewhat greater at both ends of the distribution.The government should implement differentiated health promotion programs, especially for those with greater health risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Muscular fitness (MF) reflects the ability of a muscle or group of muscles to exert force maximally, explosively, or continuously without fatigue (representing maximal muscular strength, power, and muscular endurance, respectively), as well as the ability to move a joint throughout the range of motion (flexibility)1. In childhood and adolescence, there is a negative correlation between MF and obesity, cardiovascular disease and cardiometabolic health later in life; there is a positive correlation between MF and skeletal health, and self-esteem2,3,4 Monitoring trends in MF in children and adolescents can inform the development of health promotion strategies to promote future levels of health in children and adults5. Given the importance of MF, the World Health Organization recommends that children and adolescents engage in skeletal muscle strengthening activities at least 3 days per week6.

Overall muscular endurance cannot be assessed using only a specific indicator, therefore, different tests are used among children and adolescents to assess some localized muscular endurance. The sit-ups test is a widely used measure of abdominal/trunk/core muscular endurance with good validity and high reliability and is safe7,8. Kaster et al.9 pooled data on sit-ups performance among children and adolescents aged 9–17 years from 31 countries and reported an overall improvement of 38.4% from 1964 to 2017, but this improvement has slowed down since the 21 st century and performance has declined since 2010. Trends from 1979 to 2014 in China were included in this review and performance among girls improved and then decreased. Dong et al.10 used data from girls aged 7–18 years from 1985 to 2014 and reported an improvement in 1-minute sit-ups performance from 21.3 to 27.8 repetitions (reps.). This reported trend was almost similar to the above trend, but performance rebounded from 2010 to 2014. Wang et al.11 reported that performance decreased from 30.5 reps. in 2000 to 22.7 reps. in 2010 and then increased to 26.3 reps. in 2019 in Henan, China. Evidence from Xinjiang, China, indicated that performance increased from 1985 to 1995 and then progressively decreased thereafter through 201412. Ao et al.13 reported that performance among national girls aged 12 years improved and then decreased from 1985 to 2014 in both urban and rural areas. The performance was estimated among rural Chinese girls over the past 30 years, with improvements observed during the entire period, from 1985 to 2000, from 2010 to 2019, and a decline from 2000 to 201014. In summary, the existing studies have several limitations. First, there are differences in economic levels, education and medical resources, etc., between urban and rural areas in China. Although evidence of horizontal urban-rural differences in physical fitness, including sit-up performance, among Chinese children and adolescents has been provided10,11,13, evidence of trends in urban areas is insufficient. Second, there are insufficient data or surveys on age disparities. Knowledge of this information is necessary to prioritize populations for policies and interventions to promote healthy and equitable development among children and adolescents. Third, only one study has investigated the pace of change in sit-ups performance in rural China14, and most studies have investigated only the direction of change10,11,12. Different changes in environmental factors may have different effects on the development of physical fitness over time. Fourth, informatiostributional characteristics of sit-ups performance has not been reported. Information on these trends would be necessary to determine whether these trends are even (i.e., similar for low, medium, and high performance) or uneven (i.e., different between low, medium, and high performance) in distribution and would provide an important reference for improving the MF of the total population. Moreover, given the close relationship between height, mass, body mass index (BMI) and physical fitness, especially BMI10,11, examining concurrent trends in BMI may help to gain insight into the underlying factors of changes in fitness15.

Therefore, by using the Chinese National Surveillance on Students’ Constitution and Health (CNSSCH) from 2000 to 2019, the primary purpose of this paper is to examine trends and distribution of sit-up performance among Chinese urban school-aged girls aged 7–18 years, and the secondary purpose is to provide information on height, weight, and BMI to explain changes in performance.

Methods

Study design and subjects

Body height, mass, BMI and sit-ups performance data among Han Chinese school-aged girls aged 7–18 years were obtained from published summary statistics by the CNSSCHs in 1985, 1991, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2014 and 201916,16,18,19,20,21,22,23. The CNSSCH used a multistage stratified cluster sampling design, and the sampling procedure was performed as previously described in detail10,14,15. The study included only Han Chinese students, and Han Chinese made up 91% of the total Chinese population. 30 provinces/municipalities/autonomous regions, except for Tibet, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, participated in the survey. The provincial administrations sampled in each survey year are shown in Fig. 1. Chongqing was not included in 1985, 1991 and 1995. Hainan was not included in 1985. Qinghai was not included in 1995. In the CNSSCH, the sit-ups test was used to assess muscular endurance among girls. From 1985 to 2019, 462,721, 463,688, and 463,689 girls were tested for 1-minute sit-ups, height and mass, respectively. A total of 273,474 girls aged 7–18 years were calculated for BMI (reporting of publicly available aggregated BMI data started in 2000). There were similar sample sizes in each subgroup. The test- and age-specific sample sizes among Chinese school-aged girls in each survey year are shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 1–4.

Data available according to the administrative regions in China by survey year. (A): 1985; (B): 1991; (C): 1995; (D): 2000–2019. All China maps are produced by ArcMap 10.8.1 (Esri, Redlands, CA, United States). Vector files of the maps were obtained from the National Catalogue Service of Geographic Information which was updated in 2021(https://www.webmap.cn/main.do? method=index).

Measurements

The test time for these surveys ranged from September to November. All the measuring instruments used were consistent in each survey year and were calibrated before use. Nearly 100% of the participants performed all tests at each survey site on the same day. All participants were given complete tests at all survey sites following the same protocol. The staff at all survey sites received rigorous training. Measures included:

(1) Body height: The apparatus recommended by Cameron24 was used by doctors to measure height and body mass. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm by a stadiometer.

(2) Body mass: Body mass was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg by an electronic scale, with all participants wearing underwear and barefoot.

(3) Body mass index (BMI): BMI was calculated as body mass in kilograms divided by height in meters squared [body mass (kg)/height (m)2.

(4) 1-minute sit-ups: The number of complete performances in 1 min was recorded. Detailed measurement procedures were described elsewhere16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23.

Statistical analysis

Using the published summary statistics, sample sizes, means and standard deviations (SDs) of sit-ups performance, body height, mass and BMI for urban Chinese girls by age and year are shown in Supplementary Tables 1–4. Data were classified by test and age, and best-fitting/most parsimonious sample size-weighted regressions (linear or quadratic or cubic regressions) were performed, with the independent variable being the year and the dependent variable being the results. The best model was selected by the smallest Bayesian Information Criteria. 12 age-specific models were generated in each test, for a total of 48 models. The change was expressed as absolute change (i.e., the slope of the linear regression or the derivative of the polynomial curve)25, percentage change (% per year, i.e., the slope of the regression as a percentage of the sample-weighted mean of all means in the regression), and standardized (Cohen’s) effect size (ES) (i.e., the slope of the regression divided by the combined SD of all SDs in the regression). The combined SD was calculated according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions26. A series of annual changes in each test-age-specific group were generated by the above calculations, e.g., absolute change, percentage change and ES in 1986, 1987.2019. In general, a positive ES represented improved performance and a negative ES represented decreased performance. To account for the magnitude of changes in the mean, ESs of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 were used as thresholds for small, medium, and large, respectively, with ESs of < 0.2 considered negligible changes27. Following the procedure described by Tomkinson et al.9,28, population-weighted average changes (for overall girls, girls aged 7–9 years, girls aged 10–12 years, girls aged 13–15 years and girls aged 16–18 years) were calculated for each year by combining age-specific changes using stratified population weighting in each test (Eq. 1). The population weighting was derived from the sex-region-age-specific population data from the 2020 Population Census in China29. The population census is the largest and most authoritative survey of China’s population status and is conducted every ten years. The formula was as follows:

‾Δ was the population-weighted average change, Δi was the age-specific change, wi was the age-specific population, and k was the number of years entering into the calculation of each age category. Overall changes from 1985 to 2019 (the average of 34 data points for 1986, 1987…2019 multiplied by 34) and changes per decade from 1986 to 1990 (the average of 5 data points for 1986, 1987…1990 multiplied by 10), 1991 to 2000 (the average of 10 data points multiplied by 10), 2001 to 2010 (the average of 10 data points multiplied by 10), and 2011 to 2019 (the average of 9 data points multiplied by 10) were calculated. Because only the second half of the 1980’s was observed, it was assumed that the change observed in the second half of the decade applied similarly to the first half. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the overall changes were calculated by multiplying the CI for the average change by the number of data points. The CIs for the average changes were obtained as average change ± 1.96 standard errors (SEs). SEs were calculated as the SD of the annual changes entering into the calculation in a period, divided by the square root of the number of data points (i.e. annual changes), with e.g. SD = {((‾Δ1986 - ‾x)2 + (‾Δ1987 - ‾x)2 +, … + (‾Δ2019 - ‾x)2)/34}0.5. ‾x was the overall change.

To investigate distributional characteristics, trends were estimated for each percentile value using the method described above. The test-age-specific 3rd (worst performance), 5 th, 10 th, 25 th, 30 th, 50 th, 70 th, 75 th, 90 th, 95 th, and 97 th (best performance) percentile values were extracted. Best-fitting/most parsimonious sample-weighted regressions (linear or quadratic or cubic regressions) were performed using year and percentile values. 132 region-age-percentile-specific models were generated in each test, for a total of 528 models. Locally Weighted Scatter-plot Smoother (LOWESS) curves (tension = 66)30 were used to plot changes per decade for a series of percentiles (from the 3rd to the 97 th), and the variation in change was visually examined. All the statistical analyses were performed by Stata 17.0. The a-weights were used in Stata.

Results

Trends in the 1-minute sit-ups performance, height, mass and BMI by age

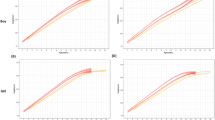

The means, standard deviations, and fitted lines of 1-minute sit-ups performance, body height, mass and BMI are shown in Figs. 2, 3, 4 and 5, respectively. Temporal changes in the 1-minute sit-ups performance, height, mass, BMI among urban Chinese girls from 1985 to 2019 according to age categories are shown in Table 2. For sit-ups performance, there was a moderate improvement in the total population from 1985 to 2019, increasing by an average of 7.2 reps. per minute or 25.7% (ES [95% CI]: 0.69 [0.08, 1.29]). Girls aged 7–9 years and 13–18 years experienced significant improvements, with no significant improvement occurring in girls aged 10–12 years (ES: 0.46 [−0.18, 1.09]) and the largest improvement occurring in girls aged 16–18 years (29.5% or 0.88 ES). For height, in the total population, there was a large increase from 1985 to 2019, increasing by an average of 5.8 cm or 4.0% (ES: 0.89 [0.81, 0.96]). Girls in all age categories experienced significant increases, with the largest increase occurring in girls aged 10–12 years (6.0% or 1.16 ES) and the smallest increase occurring in girls aged 16–18 years (2.0% or 0.55 ES). For mass, there was a large increase in the total population, increasing by an average of 8.0 kg or 20.7% (ES: 1.07 [1.02, 1.12]). Girls in all age categories experienced significant increases, with the largest increase occurring in girls aged 10–12 years (29.1% or 1.25 ES) and the smallest increase occurring in girls aged 16–18 years (12.8% or 0.86 ES). For BMI, there was a small increase from 2000 to 2019 in the total population, increasing by 1.2 kg/m2 or 6.6% (ES: 0.43 [0.38, 0.48]). Girls in all age categories experienced small increases.

Means, standard deviations and fitted lines of 1-minute sit-ups performance among urban Chinese girls aged 7–18 years from 1985 to 2019 by age. The dots represent the means and the dashed line represents the fitted lines. The best-fitting/most parsimonious sample-weighted regressions (linear or quadratic or cubic regressions) were performed.

Means, standard deviations and fitted lines of height among urban Chinese girls aged 7–18 years from 1985 to 2019 by age. The dots represent the means and the dashed line represents the fitted lines. The best-fitting/most parsimonious sample-weighted regressions (linear or quadratic or cubic regressions) were performed.

Means, standard deviations and fitted lines of body mass among urban Chinese girls aged 7–18 years from 1985 to 2019 by age. The dots represent the means and the dashed line represents the fitted lines. The best-fitting/most parsimonious sample-weighted regressions (linear or quadratic or cubic regressions) were performed.

Means, standard deviations and fitted lines of body mass index among urban Chinese girls aged 7–18 years from 1985 to 2019 by age. The dots represent the means and the dashed line represents the fitted lines. The best-fitting/most parsimonious sample-weighted regressions (linear or quadratic or cubic regressions) were performed. Body mass index data were reported only after 2000.

Trends in the 1-minute sit-ups performance, height, mass and BMI by age and period

There was a large improvement per decade in sit-ups performance among girls from 1985 to 1990 (ES: 1.05 [0.82, 1.28]), a negligible improvement per decade from 1991 to 2000 (ES: 0.04 [−0.13, 0.21]), a small decrease per decade from 2001 to 2010 (ES: −0.31 [−0.36, −0.25]), and a small improvement per decade from 2011 to 2019 (ES: 0.48 [0.24, 0.72]). Trends across age categories were generally consistent with the total population, except for a negligible decrease per decade in the performance among girls aged 7–9 years from 2001 to 2010. For height, there were small increases per decade in all periods, except from 2001 to 2010 when there was a negligible increase per decade. In terms of ES, the greatest pace of increase in height was observed from 1985 to 1990 among girls aged 7–15 years, while it was greatest from 2011 to 2019 among girls aged 16–18 years. For mass, girls in all periods experienced small increases per decade, with trends among girls in all age categories consistent with the total population, except for girls aged 16–18 years who experienced a negligible increase per decade from 1991 to 2000. In terms of ES, the increase in mass decelerated among girls aged 7–12 years and accelerated among girls aged 13–18 years and the total population. For BMI, girls experienced a negligible increase per decade from 2000 to 2010, with a small increase from 2011 to 2019. The increase in BMI accelerated among girls aged 10–18 years and the total population, and decelerated among girls aged 7–9 years (Table 3).

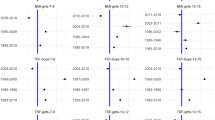

Distributional characteristics of changes in the 1-minute sit-ups performance, height mass and BMI by age

Percentile values of sit-ups performance, height, mass and BMI among urban girls aged 7–18 years in China from 1985 to 2019 by region and age are shown in Supplementary Tables 5–8 and Supplementary Figs. 1–4. Changes in ES of 1-minute sit-ups performance, height, mass and BMI among urban Chinese girls aged 7–18 years from 1985 to 2019 by percentile and age are shown in Fig. 6. For the total population, there were moderate to large improvements in sit-ups across the percentiles (ES: 0.57 to 0.93), with an approximate “U” shaped curve of percentiles versus ES. The smallest improvement occurred at the 50 th percentile (ES: 0.57), and the largest improvement occurred at the 97 th percentile (ES: 0.93). The distributional characteristics in each age category were consistent with those of the total population. For height, girls experienced moderate to large increases (ES: 0.796 to 0.99), with somewhat larger increases as the percentile increased among girls aged 16–18 years. For mass, girls experienced small to large increases (ES: 0.498 to 0.99). For BMI, girls experienced negligible to large increases from 2000 to 2019 (ES: 0.18 to 0.90). As the percentile increased, the greater the increase in mass and BMI. In particular, the ES curves of mass and BMI rose rapidly after the 85 th percentile. The distributional characteristics of mass and BMI among girls in each age category were consistent with those of the total population. The distributional effects were much stronger for body mass and BMI than for height and sit-ups performance.

Discussion

This paper estimated population-based trends in sit-ups performance, height mass and BMI among girls aged 7–18 years in urban China from 1985 to 2019. The main findings were: (a) sit-up performance of the total population increased by 7.2 reps. per minute or 25.7% or 0.69 ES from 1985 to 2019, and the improvement was greater among adolescents than among children, (b) significant increases in sit-ups performance occurred in the first 5 years and the last 9 years, and significant decreases occurred in the 2000 s, (c) improvements were somewhat greater at both ends of the distribution for sit-ups performance, (d) height and mass from 1985 to 2019 and BMI (reported only from 2000 to 2019) increased significantly, with decelerating trends for height and accelerating trends for mass and BMI, and (e) greater increases in body mass and BMI with increasing percentiles.

This study revealed that sit-ups performance among Chinese urban girls has significantly improved over the past 30 years, which is consistent with the national and Xinjiang trends from 1985 to 201410,12 and the national rural trends from 1985 to 201914. In Henan, China, performance decreased from 2000 to 201911. Compared to previous studies10,12,13, this paper added evidence from more recent time points and covered a large number of age groups, as well as providing statistically precise estimates. Data from 31 countries aggregated by Kaster et al.9 reported a decrease in sit-ups performance after 2010. However, these data were only updated until 2017, and even for many countries the data ended in 2010. Several recent updated studies reported that sit-ups performance has decreased in the last 20 years in Brazil31 and Hong Kong32,33, stabilized (curls-up) in Portugal34, and improved in Croatia35. 1-minute sit-ups performance improved among Slovenian girls aged 7–15 years from 1989 to 2019, but the trend was steadier in the last few years36. It can be observed that performance has improved in some countries recently. However, there are still significant differences in trends between countries, and with the exception of some country-specific factors, the methodology of the statistical analyses may also introduce errors.

Some studies have suggested that biological maturity, body size and physical activity may influence muscular endurance performance9,37. The improvements in sit-ups performance may be explained by advances in biological maturation. Older children usually perform better than younger children because of improved physical and neuromuscular maturation38. A survey from CHSSCH showed that the median ages at menarche progressively decreased from 13.37 to 12.00 years among Chinese urban girls from 1985 to 201939. This trend seems to correspond to the overall trend in sit-up performance observed in this study but does not explain the large decrease from 2001 to 2010. Kaster et al.9 corrected the estimated international trend in sit-ups performance by the trend in biological maturation and reported that the improvement in performance decreased by only a few percentage points from the uncorrected level. This suggests that trends in biological maturation explain only a small part of the trend in sit-ups performance.

Many studies adjusted for trends in height, mass, or BMI when estimating trends in sit-ups performance. Several studies reported that temporal trends in sit-ups performance were independent of, or rarely associated with, trends in body size5,9,31, noting that most countries in these studies were developed countries. Other studies reported concurrent trends in sit-ups performance and height, mass, or BMI, with the two trends either in opposite33 or the same direction35,36. The present study revealed that height and mass among girls from 1985 to 2019, and BMI from 2000 to 2019 progressively increased in the same direction as the general trend of sit-ups performance. In recent decades, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in Chinese girls has gradually increased, the prevalence of thinness and multiple components of physical fitness has decreased, and the main nutritional problem in China has shifted from malnutrition to overnutrition10,11. How and to what extent these two nutritional problems affect sit-ups performance are currently unknown. In addition, BMI cannot distinguish between muscle mass and fat mass (FM). In general, increased FM increases additional loading during exercise, whereas increased muscle mass increases muscle strength, although its effect on sit-up performance is less clear. Unfortunately, few studies have estimated trends related to FM. A survey in Shandong, China, reported that skinfold thickness (SFT) increased by 14% from 1995 to 2010 among girls and that body mass, FM and fat-free mass (FFM) continued to increase, with the percentage of increase in FM being greater than that in FFM40. The prevalence of ‘high SFT’ increased from 13.4% in 1995 to 29.3% in 2014 among girls in Shandong41. In Hong Kong, the trend in sum of skinfolds was opposite to the trend in sit-ups performance33, but triceps skinfolds showed the same trend as sit-ups in Slovenia36.

Few studies have controlled for physical activity (PA) factors in estimating trends in sit-ups performance, but several have reported their concurrent trends. Between 2008 and 2014, sit-ups performance among British girls aged 10 years decreased by 6.9 reps. per 30 s, and the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Children (PAQ-C) score decreased by 0.375. In European countries, there was a positive correlation between temporal trends in vigorous physical activity and trends in sit-ups performance9. Several studies have suggested that the trend in PA is a key factor contributing to changes in sit-ups performance9,31,42. A study from the China Health and Nutrition Survey reported that total PA among girls aged 6–17 years decreased from 36.3 metabolic equivalent of task hours/week to 31.0 h/week from 2004 to 2015, with the main decrease in school PA43; total sedentary time increased by 1.3 h/week but decreased after 201144. Guo et al.45 reported no significant change in the percentage of Chinese girls with PAQ-C scores greater than 2.87 (equivalent to daily moderate-to-vigorous physical activity greater than one hour) from 2017 to 2019, but the percentage of daily recreational screen time less than two hours decreased from 89.5 to 83.3%. The percentage of girls aged 9–18 years with in-school PA for more than one hour per day increased from 20.1 per cent to 40.0 per cent between 2010 and 201946. The trend in PA appears to be consistent with the trend in sit-ups performance since the beginning of the 21 st century reported in this study. Unfortunately, earlier PA data were not available. In addition, Chinese policies may also be an important indirect factor contributing to the positive trend in performance in recent years. In 2007, the Chinese government first identified the promotion of students’ physical health as one of the strategies for national development. Since then, a series of strategies to promote PA have been launched, such as guaranteeing students one hour of PA in school and improving physical education and health courses10,12,14,15.

Age-stratified results revealed no significant improvement in sit-ups performance among girls aged 10–12 years, with greater improvement in sit-ups performance among girls aged 13–18 years. Dang et al.47 reported that the prevalence of overweight and obesity among urban girls aged 10–12 years has increased the most over the past 30 years compared to the other age categories, becoming the group with the worst prevalence by 2019. Moreover, 10–12 years of age is the onset of puberty for girls in recent years39,47, and the onset of puberty has been found to be associated with obesity48. PA levels decreased among children aged 6–11 years from 2004 to 2015 and did not change significantly among adolescents aged 12–17 years43. Progress in biological maturity, changes in nutritional status and PA may explain the trends in this age category. However, the trend over the last 9 years revealed that urban girls aged 16–18 years presented the smallest increase in performance, which may be related to the smaller increase in their physical activity levels in recent years compared with other age categories46. Over the last 30 years, Chinese students have been increasingly academic burdened with inadequate physical education classes, spending more time on the Internet to compress their time for PA, and students’ PA behaviors decrease with age14. Interestingly, for girls aged 13–15 years, a greater improvement in sit-ups performance was observed in the last 9 years, which may be related to the policy in China. Most of them were in junior high school, and after 2007, China gradually started to implement the Physical Education Entrance Examination for Senior High School, which requires junior middle school students to compulsorily take physical education exams when they enter junior high school if they do not have special situations, e.g., sudden illnesses or physical defects, and this has encouraged them to engage in physical exercise14,15.

Trends in sit-ups performance were not always consistent across the population distribution. The smallest improvement was observed in the medium-quality population, and the greatest improvement was observed in the populations with poorer or better sit-ups performance. In Brazil, although sit-ups performance has declined, there has still been an improvement in some parts of the population, with an expanded distribution31. The findings from Hong Kong differed from those of this paper, where although sit-ups performance decreased, the performance of the population with better performance improved, with more positive changes as the percentile increased32,33. Variability in trends was also observed in cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) among Chinese girls, with decreases in CRF mainly contributed by the population with poorer performance and conversely increases mainly contributed by the population with better performance14. One possible psychological explanation is that girls with poorer performance may be less inclined to engage in PA and other healthy habits than their peers with better performance are49. Another explanation is that girls generally pursue a “flat” abdomen42. With the increasing popularity of television advertisements and the internet, an increasing number of girls are looking for “thin” beauty, and they may adopt poor diets to control their weight. Although they are less physically fit, they may engage in additional abdominal exercises to achieve a flat abdomen. In addition, as there are no negative values for sit-ups performance, the worst performance is 0. If the health of the population increases, the increase may be more pronounced in the low-base population than in the average population. Owing to the inability to examine concurrent trends in other relevant factors and the limitations of cross-sectional studies, it was not possible to determine how other factors affect sit-ups performance in populations by performance level. Future studies should examine performance trends and associated influencing factors in populations with different performance levels. In conclusion, the present findings emphasize the need for interventions for girls with lower performance levels. In addition, according to the National Student Physical Fitness Standards of China (2014 Revision), in 2019 girls in almost all age groups achieved “passing” in sit-ups performance at the 25 th percentile, “good” at the 90 th percentile, and “excellent” at the 95 th percentile50. In other words, about a quarter of the girls did not meet the “passing” level. It is suggested that more attention should be given to girls with poor performance by increasing their lumbar and abdominal strength training and monitoring their active participation in PA. For girls with “good” or even “excellent” performance on sit-ups, it is proposed that they should be trained mainly in the poor component of physical fitness, encouraging rather than pressuring them to participate in PA.

This paper provides the first temporal trends in sit-ups performance, height, mass, and BMI in urban Chinese girls over the past 30 years. Nationally representative physical health surveillance data were used. Weighted regression and post-stratification population weighting procedures helped to control for sampling bias by incorporating potential demographic information. This study has several limitations. First, given the use of publicly available summary statistics and the unavailability of raw data, statistical adjustments for body size, biological maturity, and PA levels were not possible. However, concurrent trends in height, weight, and BMI were provided, which provided some insight into trends in sit-ups performance. Second, given the limitations of the data, the lambda mu-sigma method could not be used to calculate percentile values for the test means, which may introduce some errors by ignoring the skewness and dispersion of the data. However, the sample size of this study was very large, which may minimize these errors. Finally, the sit-up test in the CNSSCH was performed only in girls, and in the future, this test should be added for boys; alternatively, another common program for both sexes should be used to investigate sex differences in muscular endurance.

Conclusion

Sit-ups performance among girls aged 7–18 years in urban China improved from 1985 to 2019, with improvement being the main trend across periods, but a significant decrease was observed from 2000 to 2010. Height, mass, and BMI continued to increase, but there were some age differences, also in sit-ups performance. Improvement was somewhat greater at both ends of the distribution of sit-ups performance and there were significant greater increases in the high percentile of mass and BMI. Biological maturity, nutritional status and PA levels may be relevant factors. More health promotion strategies, especially regarding PA, should be implemented and monitored. Moreover, the government and relevant departments should pay attention to populations with poorer performance and prioritize physical education programs and policies to promote equal development of the total population.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files). The CNSSCHs dataset can be found in the following publicly available books, Refs 16-23 and also is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2018).

García-Hermoso, A., Ramírez-Campillo, R. & Izquierdo, M. Is muscular fitness associated with future health benefits in children and adolescents?? A systematic review and Meta-Analysis of longitudinal studies. Sports Med. 49, 1079–1094 (2019).

Smith, J. J. et al. The health benefits of muscular fitness for children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 44, 1209–1223 (2014).

Artero, E. G. et al. Muscular and cardiorespiratory fitness are independently associated with metabolic risk in adolescents: the HELENA study. Pediatr. Diabetes. 12, 704–712 (2011).

Sandercock, G. R. H. & Cohen, D. D. Temporal trends in muscular fitness of english 10-year-olds 1998–2014: an allometric approach. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 22, 201–205 (2019).

World Health Organization. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health (WHO, 2010).

Plowman, S. A. Muscular Strength, Endurance, and Flexibility Assessments (Cooper Institute, 2014).

Contreras, B. & Schoenfeld, B. To crunch or not to crunch: an Evidence-Based examination of spinal flexion exercises, their potential risks, and their applicability to program design. Strength. Cond J. 33, 8–18 (2011).

Kaster, T. et al. Temporal trends in the sit-ups performance of 9,939,289 children and adolescents between 1964 and 2017. J. Sports Sci. 38, 1913–1923 (2020).

Dong, Y. et al. Trends in physical fitness, growth, and nutritional status of Chinese children and adolescents: a retrospective analysis of 1·5 million students from six successive National surveys between 1985 and 2014. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health. 3, 871–880 (2019).

Wang, X. et al. Temporal trends in physical fitness among Chinese children and adolescents from 2000 to 2019 and analysis of social-ecological factors. J. Sports Sci. 41, 884–894 (2023).

Bi, C., Zhang, F., Gu, Y., Song, Y. & Cai, X. Secular trend in the physical fitness of Xinjiang children and adolescents between 1985 and 2014. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 7, 2195 (2020).

Ao, D., Wu, F., Yun, C. F. & Zheng, X. Y. Trends in physical fitness among 12-Year-Old children in urban and rural areas during the social transformation period in China. J. Adolesc. Health. 64, 250–257 (2019).

Li, C., Taerken, A. Y., Li, Q., Selimu, A. & Wang, H. Secular trends in physical fitness of rural Chinese children and adolescents aged 7–18 years from 1985 to 2019. Sci. Rep. 13, 4229 (2023).

Li, C., Zhang, J., Maisiwute, M., Zhou, Z. & Zang, L. Temporal trends and distributional changes in cardiorespiratory fitness among Chinese children and adolescents from 1985 to 2019. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 34, e14669 (2024).

National Student Physical Fitness and Investigation Group. Report on the Physical Fitness and Health Surveillance of Chinese School Students in 1985 (People’s Educational Publication, 1987).

National Student Physical Fitness and Investigation Group. Report on the Physical Fitness and Health Surveillance of Chinese School Students in 1991 (Beijing Technical and Science, 1993).

National Student Physical Fitness and Investigation Group. Report on the Physical Fitness and Health Surveillance of Chinese School Students in 1995 (Jilin Technical and Science Publication, 1997).

National Student Physical Fitness and Investigation Group. Report on the Physical Fitness and Health Surveillance of Chinese School Students in 2000 (Higher Education Press, 2002).

National Student Physical Fitness and Investigation Group. Report on the Physical Fitness and Health Surveillance of Chinese School Students in 2005 (Higher Education Press, 2007).

National Student Physical Fitness and Investigation Group. Report on the Physical Fitness and Health Surveillance of Chinese School Students in 2010 (Higher Education Press, 2012).

National Student Physical Fitness and Investigation Group. Report on the Physical Fitness and Health Surveillance of Chinese School Students in 2014 (Higher Education Press, 2016).

National Student Physical Fitness and Investigation Group. Report on the Physical Fitness and Health Surveillance of Chinese School Students in 2019 (Higher Education Press, 2022).

Cameron, N. The Methods of Auxological Anthropometry (Plenum, 1978).

Tomkinson, G. R. et al. Temporal changes in long-distance running performance of Asian children between 1964 and 2009. Sports Med. 42, 267–279 (2012).

Higgins, J. P. T. et al. (eds) JChapter 6: Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect. In:,,Welch, V. A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5 Cochrane, (2024).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1988).

Tomkinson, G. R. et al. Temporal trends in the standing broad jump performance of 10,940,801 children and adolescents between 1960 and 2017. Sports Med. 51, 531–548 (2021).

Office of the Leading Group for the Seventh National Population Census of the State Council. Major Figures on 2020 Population Census of China (China Statistics, 2021).

Cleveland, W. & Devlin, S. Locally weighted regression: an approach to regression analysis by local fitting. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 83, 596e610 (1988).

Nevill, A. M., Duncan, M. J., Gaya, A. & Mello, J. B. Secular trends in the physical fitness of Brazilian youth: evidence that fitness is declining for the majority but not for a fit minority. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 33, 2079–2089 (2023).

Poon, E. T., Tomkinson, G. R., Lang, J. J., Huang, W. Y. & Wong, S. H. Temporal trends in the physical fitness of Hong Kong children aged 6–12 years between 2003-04 and 2015-16. J. Sports Sci. 41, 1271–1278 (2023).

Poon, E. T., Tomkinson, G. R., Huang, W. Y. & Wong, S. H. Temporal trends in the physical fitness of Hong Kong adolescents between 1998 and 2015. Int. J. Sports Med. 44, 728–735 (2023).

Rosa, G. B. et al. Physical fitness trends in a nationally representative sample of Portuguese youth: what has changed from 2008 to 2018? Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 33, 2058–2067 (2023).

Kasović, M., Štefan, L. & Petrić, V. Secular trends in health-related physical fitness among 11-14-year-old Croatian children and adolescents from 1999 to 2014. Sci. Rep. 11, 11039 (2021).

Radulović, A., Jurak, G., Leskošek, B., Starc, G. & Blagus, R. Secular trends in physical fitness of Slovenian boys and girls aged 7 to 15 years from 1989 to 2019: a population-based study. Sci. Rep. 12, 10495 (2022).

Joensuu, L. et al. Physical fitness development in relation to changes in body composition and physical activity in adolescence. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 31, 456–464 (2021).

Tomkinson, G. R. et al. European normative values for physical fitness in children and adolescents aged 9–17 years: results from 2779165 Eurofit performances representing 30 countries. Br. J. Sports Med. 52, 1445–14563 (2018).

Ma, N. et al. Secular trends and urban-rural disparities in the median age at menarche among Chinese Han girls from 1985 to 2019. World J. Pediatr. 19, 1162–1168 (2023).

Zhang, Y. X. & Wang, S. R. Changes in skinfold thickness and body composition among children and adolescents in Shandong, China from 1995 to 2010. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 26, 252–258 (2013).

Wang, S. R., Cheng, Y., Chen, M. & Zhang, Y. X. Trends in the prevalence of elevated skinfold thickness among children and adolescents in Shandong Province, China, 1995–2014. Public. Health Nutr. 21, 2238–2241 (2018).

Đurić, S. et al. Secular trends in muscular fitness from 1983 to 2014 among Slovenian children and adolescents. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports. 31, 1853–1861 (2021).

Yang, X., Leung, A. W., Zhai, Y. & Zhao, W. H. Recent trends in physical activity among Chinese children based on their demographic and social characteristics. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 34, 404–409 (2021).

Yang, X., Leung, W. Y., Chen, Y. S., Ouyang, Y. F. & Zhao, W. H. Recent trends in sedentary behaviors among Chinese children according to demographic and social characteristics. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 34, 593–605 (2021).

Guo, M. M., Koh, K. T. & Wang, X. Z. Trends of physical activity and recreational screen time among Chinese children and adolescents: a National study from 2017 to 2019. BMC Public. Health. 24, 1305 (2024).

Zhong, P. L. et al. Trends of prevalence rates of daily on-campus physical activity of Chinese Han students aged 9–18 years from 2010 to 2019. Chin. Prev. Med. 24, 36–43 (2023). (in Chinese).

Dang, J. et al. Secular trend and projection of overweight and obesity among Chinese children and adolescents aged 7–18 years from 1985 to 2019: rural areas are becoming the focus of investment. Chin. Med. J. https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000003123 (2024).

Reinehr, T. & Roth, C. L. Is there a causal relationship between obesity and puberty? Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health. 3, 44–54 (2019).

Zheng, W. et al. The Relationship between Physical Fitness and Perceived Well-Being, Motivation, and Enjoyment in Chinese Adolescents during Physical Education: A Preliminary Cross-Sectional Study. Children 10, 111 (2023).

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. Notice of the Ministry of Education on the issuance of the National Student Physical Fitness Standard. Revision) (accessed 7 February 2025). (2014). http://www.moe.gov.cn/s78/A17/twys_left/moe_938/moe_792/s3273/201407/t20140708_171692.html (2014-07-07).

Acknowledgements

We thank all staff who worked on the Chinese National Survey on Students’ Constitution and Health in 1985, 1991, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2014 and 2019.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the Scientific Research Project of Hunan Provincial Department of Education in 2024 (24B1093); the Project of Hunan Provincial Social Science Achievement Review Committee in 2025 (XSP25YBC148); and the Project of Hunan Provincial Education Science “14th Five-Year Plan” (XJK23BTW009). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jianwu Liu and Shengbin Wu: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing. Ying Fu: resources, software, validation, visualization, writing-review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable. The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The data analyzed during this study from CNSSCHs have been published openly and are freely available. The data can be found in the following publicly available books, Refs 16-23.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Wu, S. & Fu, Y. Population-based trends and distributional characteristics in sit-ups performance among school-aged girls in urban China over three decades. Sci Rep 15, 16750 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01192-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01192-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Eroding lineages: age structure and intergenerational risks in small-scale fisheries

Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries (2026)

-

Trends and distributional characteristics in handgrip strength of 1,082,296 children and adolescents in China: an analysis from five representative cross-sectional surveys from 2000 to 2019

BMC Public Health (2025)