Abstract

The body roundness index (BRI) accurately assesses body composition and visceral fat distribution, but its independent associations with cognitive function and cognitive impairment remain unclear. This study, which is based on data from the 2011–2014 U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), explores the associations between the BRI and cognitive function as well as cognitive impairment in older adults. Weighted linear regression and weighted logistic regression models were used for data analysis. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) models, subgroup analysis, and mediation analysis were conducted to explore effect modification, nonlinear associations, and the mediating role of depression. The BRI score was negatively correlated with the cognitive function score (DSST score β = -0.63, P = 0.037; Sum Score β = -0.83, P = 0.042) and was not significantly associated with cognitive impairment. As the BRI score increases, both the DSST score (trend P = 0.013) and the Sum Score (trend P = 0.023) show a linear decrease. The mediation effect analysis revealed that depression mediated 39.4% of the association between the BRI score and cognitive function, suggesting that the effect may be indirectly mediated through mental health pathways. Subgroup analysis and RCS models did not reveal significant interaction effects or nonlinear associations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global aging of the population is accelerating, and it is projected that the number of people aged 65 and above will double by 20501. As people age, the structure and function of the brain gradually deteriorate, leading to a decline in cognitive function, including impairments in attention, memory, executive function, language ability, and visual-spatial skills2,3. If left unchecked, these changes may progress to mild cognitive impairment or dementia4.

Obesity, especially visceral obesity, is closely related to cognitive decline5. The metabolism of visceral fat is active, which easily leads to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and inflammation and other metabolic disorders6,7. These factors significantly increase the risk of cognitive decline8. Traditional obesity indicators such as body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC) have limitations9. They cannot accurately reflect the ratio of fat to muscle10 or distinguish between visceral fat and subcutaneous fat, and are insensitive to height differences11. The body roundness index (BRI) quantifies the geometric shape of the trunk and can more sensitively reflect the distribution of visceral fat12. The BRI has shown strong fat distribution prediction ability and is an effective indicator for evaluating visceral obesity13. A large number of studies have shown that the BRI is an independent risk factor for hypertension14,15, diabetes16,17, metabolic syndrome18, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease19, and osteoarthritis20. A large-scale cross-sectional study based on 26,332 samples showed that among 12 conventional anthropometric indicators, BRI demonstrated the best diagnostic efficacy in discriminating the normal weight phenotype of metabolic obesity, and its accuracy was significantly superior to BMI and WC, etc21. A recent cohort study targeting the elderly population in Taiwan, China, confirmed that an increase in BRI is significantly associated with cognitive decline22. In terms of mechanism, visceral fat induces hippocampal damage by releasing pro-inflammatory factors (such as IL-6, CRP)23, insulin resistance and hyperglycemia exacerbate β-amyloid protein deposition and tau protein pathological formation, and these factors may jointly accelerate cognitive decline24,25.

Depression is an important risk factor for cognitive decline26, especially among the elderly population, and has been regarded as an independent factor that triggers or aggravates cognitive impairment27. Studies have shown that depression significantly affects an individual’s cognitive function through exacerbating memory problems and reducing cognitive processing speed28. Depression often coexists with obesity. Obesity promotes the occurrence of depression through mechanisms such as fat accumulation, dysbiosis of the intestinal flora, and overactivation of the HPA axis, while depression further impairs cognitive function29,30.

At present, there is no research exploring the mediating role of depression between BRI and cognitive function. This study aims to assess the potential mediating role of depression and clarify the association between BRI and cognitive function. The research hypotheses are as follows: (1) BRI is negatively correlated with cognitive function and positively correlated with cognitive impairment; (2) Depression plays a mediating role between BRI and cognitive function.

Methods

Study description and population

The NHANES is an ongoing national survey series that collects cross-sectional representative health data from the general U.S. population every two years. The NHANES program includes household interviews, physical examinations, and laboratory tests on a selected sample of the non-institutionalized U.S. population, employing a complex multi-stage probability sampling design (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm). The procedures and protocols of the NHANES have been approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

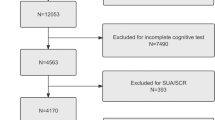

Since cognitive function testing was only conducted for individuals aged 60 and older during the 2011–2012 and 2013–2014 NHANES cycles, this study extracted de-identified data for this age group. Strict inclusion criteria were applied to ensure the relevance and accuracy of the data. We excluded 16,299 participants under 60 years of age, 698 participants with incomplete cognitive function data, 178 participants with missing BRI data, and 41 participants with missing covariate data. Ultimately, the final sample consisted of 2,715 participants (Fig. 1). This research adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting requirements.

Cognitive function

The NHANES performs cognitive evaluations for individuals aged 60 years and above. Cognitive function was assessed via three methods: the CERAD word list learning test, the animal fluency test (AFT), and the digit symbol substitution test (DSST).

The CERAD precisely evaluates an individual’s capacity to acquire new linguistic information, both immediately and after a delay, thereby indicating memory function, particularly in vocabulary acquisition and retrieval. It signifies a crucial aspect of cognitive function associated with language memory. The AFT evaluates categorical verbal fluency, an aspect of executive function utilized to differentiate between normal cognitive function, mild cognitive impairment, and more severe cognitive impairments, including Alzheimer’s disease. The participants were tasked with enumerating as many animals as possible within one minute, earning one point for each name provided. The DSST is a component of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS III) that evaluates processing speed, attention, and working memory. The assessment necessitates that participants correlate numbers with symbols within a 2-minute timeframe, yielding findings on the basis of the quantity of accurate matches. The total score of these three items is called the Sum Score.

We utilized Z-transformation to standardize each test score to establish a comprehensive measure of cognitive performance31. The standardized scores (AFT_Z, CERAD_Z, and DSST_Z) were aggregated into a composite score, “Sum Score_Z”, reflecting the individuals’ overall cognitive performance in this study. In all assessments, elevated results signify superior cognitive performance32. No definitive threshold value for cognitive impairment has been established in other investigations. Nevertheless, the current study utilized the 25 th percentile of DSST scores as a criterion for detecting cognitive impairment33.

Assessment of body roundness indices

The BRI is calculated via the formula proposed by Thomas et al.12. The equation is as follows:

WC and height were measured by staff at the mobile examination center. Owing to the lack of established reference ranges, the BRI is divided into four groups corresponding to the 25 th, 50 th, and 75 th percentiles to facilitate further analysis of its association with cognitive function.

Covariate assessment

The selection of covariates was based on relevant prior literature and internal discussions within the research team34,35. The covariates in this study were demographic traits, health-related lifestyle factors, pertinent chronic conditions, and depressive symptoms. The categorical variables included gender(male, female), age (60–69, 70–79, ≥ 80), ethnicity (Mexican American, other Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, other/multiracial), education (< 9 th grade, 9–12 th grade, > 12 th grade), marital status (living with partner/living alone), the poverty-income ratio (PIR), smoking status, alcohol status, hypertension, diabetes, and depression.

PIR was defined as the ratio of household income to the poverty threshold: income below the poverty threshold was indicated by a value of < 1.3, income between 1.5 and 3.5 was indicated by a value of 1.5–3.5, and income above the poverty threshold was indicated by a value of > 3.5. Three categories were created on the basis of smoking status: never smoked (less than 100 cigarettes), past smoker (more than 100 cigarettes but no longer smoking), and current smoker (more than 100 cigarettes and presently smoking daily or occasionally). Three categories were used to classify alcohol status: never drank (fewer than 12 drinks in a lifetime), former drinker (more than 12 drinks in a single year and no drinking in the previous year, or more than 12 drinks in a lifetime but not last year), and current drinker (more than 12 drinks and drinks daily or occasionally). Answers to the questions “Has a doctor ever told you that you have high blood pressure?” and “Have you been told that you have high blood pressure more than twice?” were used to establish the presence of hypertension. “Has a doctor ever told you that you have diabetes?” was used to confirm diabetes status. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 was used to measure depression, and a total score of ≥ 10 indicated depression36.

Statistical analysis

Using the suggested weighting scheme, all analyses carried out in this study complied with the criteria specified in the CDC guidelines. Interview weights were applied according to NCHS guidelines. For regularly distributed samples, t tests and analysis of variance were utilized, whereas for nonnormally distributed samples, the Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests were applied. Continuous variables were characterized by mean values and standard deviations and compared via t tests, whereas categorical variables were represented as unweighted frequency counts and weighted percentages and were evaluated via chi-square tests. Multicollinearity in the multivariable model was assessed by calculating the generalized variance inflation factor (GVIF), with variables with a GVIF value exceeding 5 excluded. No multicollinearity was detected among the variables (Table S1).

The BRI was divided into quartiles (the first quartile served as the reference group). Weighted linear regression was used to explore the association between the BRI score and the three cognitive function scores (CERAD, AFT, DSST) as well as the Sum Score, and weighted logistic regression was used to explore the association between the BRI score and cognitive impairment. Covariates were identified through a literature review13,37. Our analyses involved four models: the crude model, which was unadjusted; Model 1, which was adjusted for age, gender, and ethnicity; Model 2, which was further adjusted for PIR, education, and marital status; and Model 3, which included adjustments for additional variables, such as smoking status, alcohol status, hypertension, diabetes, and depression. To assess trends in nonlinear associations between the BRI and various indicators of cognitive function and cognitive impairment, we conducted analyses via a three-node restricted cubic spline (RCS) model, with Wald tests for overall P and nonlinear P. The RCS plots were adjusted for all covariates. Subgroup analyses were conducted to examine the heterogeneity in the association between BRI and cognitive impairment, with forest plots used to illustrate the effect sizes across subgroups.

In this study, mediation analysis was conducted using the “mediation” package38 in R. The following steps were taken to examine the mediating effect of depression on the association between the BRI and cognitive function: (1) assessing the total effect of the BRI on cognitive function (path c), (2) testing the direct effect of the BRI on cognitive function while controlling for depression (path c’), (3) estimating the indirect effect of depression as a mediator between the BRI and cognitive function (path a * path b), and (4) calculating the proportion mediated by depression (indirect effect/total effect). The significance of the mediation effect was tested using the percentile bootstrap method (1000 replicates). A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.4.1. Missing data were imputed using the ‘mice’ package, a statistical method based on Bayesian inference and regression modeling.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

A total of 2715 elderly patients were enrolled in the study. The median age of the participants was 69.25 [63, 75] years, with 1,388 female (54%) and 1,327 male (46%). The overall prevalence of cognitive impairment in the study cohort was 13%. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the study population categorized by BRI quartiles. Overall, the four quartiles showed statistically significant differences in gender, ethnicity, education, marital status, PIR, smoking status, alcohol status, hypertension, diabetes, depression, CERAD and DSST (P < 0.05). The means of the CERAD score, AFT score, DSST score, Sum Score, CERAD_Z, AFT_Z, DSST_Z, and Sum Score_Z were 26.22 ± 6.27, 18.35 ± 5.66, 52.91 ± 16.41, 97.48 ± 23.89, 0.18 ± 0.98, 0.29 ± 1.04, 0.38 ± 0.96, and 0.38 ± 0.99, respectively. Table S2 displays the population characteristics grouped by cognitive impairment status.

Associations between the body roundness index and the CERAD, AFT, DSST and Sum Score

Table 2 presents the results of the multivariable linear regression analysis of the associations between the BRI and cognitive function. Our study revealed that in the unadjusted crude model, a higher BRI was significantly negatively correlated with cognitive function, especially the DSST score (β = −0.63, 95% CI: −1.2, −0.04, P = 0.037) and Sum Score (β = −0.83, 95% CI: −1.6, −0.03, P = 0.042). The participants in the highest BRI quartile (Q4) had a DSST score that was 3.6 points lower than that in the Q1 group (β = −3.6, 95% CI: −6.8, −0.42, P = 0.028) and a Sum Score that was 5.0 points lower (β = −5.0, 95% CI: −9.4, −0.49, P = 0.031). Trend analysis revealed that higher BRI scores were associated with lower DSST scores (trend P value = 0.013) and lower Sum Scores (trend P value = 0.023), suggesting a potential dose-response relationship. However, as covariates were progressively adjusted for, the above associations gradually weakened. According to the fully adjusted model, no significant associations were found between BRI scores and cognitive function scores (P > 0.05).

Associations between body roundness index and cognitive impairment

Table 3 presents the results of the logistic regression analysis on the association between BRI and cognitive impairment. According to the crude model, for every 1-unit increase in BRI, the possibility of cognitive impairment increases by 7% (OR = 1.07, 95% CI: 1.0–1.16, P = 0.066). After dividing BRI into four equal parts, the crude model shows that the possibility of cognitive impairment in the Q4 group is slightly higher than that in the Q1 group (OR = 1.49, 95% CI: 0.95–2.35; P = 0.081). In the model 3, the effect sizes of each quartile group are unevenly distributed (Q1: OR = 1; Q2: OR = 0.88; Q3: OR = 0.90; Q4: OR = 0.93).

Subgroup analysis and restricted cubic spline analysis

A subgroup analysis forest plot (Fig. 2) was generated using weighted logistic regression. The results showed no significant differences in the association between BRI and cognitive impairment across the analyzed subgroups (P for interaction > 0.05).

RCS analysis revealed no significant nonlinear association between the BRI score and the four scores (CERAD, AFT, DSST, and Sum Score) (P-nonlinear > 0.05) (Fig. 3). In the crude model (Fig. 4-A), the association between BRI and cognitive impairment was not significant. However, in the partially adjusted models (Fig. 4B and 4-C) and the fully adjusted model (Fig. 4-D), a significant overall association between a higher BRI and cognitive impairment was observed (P-overall < 0.01), while the nonlinear association remained non-significant.

The results of the RCS subgroup analysis showed that a higher BRI was associated with a greater likelihood of cognitive impairment, with this association being more pronounced in subgroups of male, individuals aged 80 and above, non-White populations, those with low income, those with low education levels, those living alone, current smokers, and those with depression (Fig. 5).

Mediation analyses

Through independent analyses of the associations among the BRI, depression, and cognitive function, we found a significant association between the BRI and depression (Tables S3-S4). Therefore, we further investigated the potential mediating role of depression in the associations between the BRI score and cognitive function (Tables S5-S8, Fig. S1). The results of the mediation analysis, as shown in Fig. 6, revealed that depressive symptoms significantly mediated the associations between the BRI score and cognitive function (mediated proportion = 39.4%; indirect effect = −0.207, [−0.281, −0.14], P < 0.001). The total effect was − 0.523 [−0.802, −0.22], P < 0.001. When controlling for depression, the direct effect of the BRI on cognitive function remained significantly negative, with a value of −0.316 [−0.597, −0.03], P < 0.05.

Discussion

This study aims to explore the association between BRI and cognitive function in the elderly population, as well as the role of depression in this relationship. The results showed that there was a significant negative association between the increase of BRI and the decrease of DSST scores and Sum Score. This indicates that the increase of BRI may be accompanied by a gradual decline in cognitive function. Additionally, the mediation analysis demonstrated that depressive symptoms played a key mediating role in this association, with a mediation proportion of 39.4%, suggesting that BRI may affect cognitive function through dual pathways of psychology and biology.

We found that in the elderly population of the United States, BRI was significantly negatively correlated with cognitive function, which was consistent with previous studies39,40,41. In a large cohort study in Taiwan, China, BRI was inversely proportional to cognitive function. The higher the BRI, the lower the MMSE score22. Similarly, a cross-sectional study in China involving 2,577 middle-aged and elderly individuals also found that BRI was significantly associated with the possibility of cognitive impairment, suggesting that BRI could serve as a potential predictive indicator for cognitive decline39. A longitudinal aging study in the UK42 indicated that there was a correlation between waist-to-height ratio and body shape index and cognitive decline; however, after controlling for confounding variables, this relationship weakened, and the results were consistent with our study. This suggests that when potential confounding factors are considered, the independent effect of BRI on cognitive function may be limited to a certain extent.

Several potential mechanisms have been proposed to explain the associations between the BRI and cognitive function. Firstly, obesity is closely associated with the decline of cognitive function in the elderly, especially for individuals with higher BMI or body fat content, who have a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia5,43. Study shows that even after controlling for age, gender, cardiovascular health and other risk factors, patients with increased central fat content experience a faster decline in cognitive ability44. Secondly, the accumulation of visceral fat is significantly associated with the deposition of β-amyloid protein in the brain, as well as the decline in language learning and language memory abilities45. Adults with a higher visceral fat index exhibit more pronounced memory loss, subcortical gray matter atrophy, and hippocampal atrophy, and the intensity of these changes increases with age46. Studies evidence also suggest that obesity and inflammation may cause hippocampal dysfunction by altering brain structure of neurons25. Meanwhile, insulin resistance promotes the excessive phosphorylation of tau protein, exacerbating neurofibrillary tangles23,24,47. Insulin resistance inhibits dopamine signal transduction and reduces the efficiency of task switching48. Furthermore, metabolic disorders associated with obesity, such as hyperlipidemia, hypertension and abnormal blood sugar levels, are also closely related to the occurrence of cognitive impairment49,50. They can aggravate oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, thereby damaging neural functions and reducing cognitive abilities8,40.

Another key finding of this study is that depressive symptoms mediate 39.4% of the associations between the BRI score and cognitive function, indicating their crucial role in explaining this association. Even after accounting for depressive symptoms, the BRI still exerts a direct effect on cognitive function, further validating our hypothesis. Obesity influences the onset of depression through multiple mechanisms, including the promotion of oxidative stress, disruption of the gut microbiome, activation of the HPA axis, interference with synaptic plasticity, and alterations in neurotransmitter signaling, all of which ultimately lead to the development of depression29,30. The research conducted by Zhang et al.34 indicates that there is a significant correlation between BRI and depression. For every 1-unit increase in BRI, the incidence of depression will rise by 8%. Concurrently, depression may lead to reduced cerebral perfusion and changes in brain receptors (e.g., NMDA receptors), particularly in regions such as the anterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, and parietal lobes51. These physiological changes further contribute to cognitive decline, brain atrophy, and the progression of neurodegenerative diseases52. Moreover, the association of obesity on cognitive function is modulated by depression, as obesity and depression often cooccur, potentially amplifying the detrimental effects of obesity on cognitive health35,53. This finding underscores the complexity of the associations among obesity, mental health, and cognitive decline.

Strength

One key strength of this study lies in the use of a nationally representative sample with diverse racial groups. Compared with previous studies, our research, with its large sample size and weighted data, ensures that the results more accurately reflect the U.S. elderly population, thus enhancing statistical stability. Moreover, while many prior studies have focused primarily on BMI or other obesity indicators, our study uniquely emphasizes the BRI, a more precise measure of central obesity and fat distribution, allowing for a more detailed assessment of its associations with cognitive health. This approach makes the BRI a potentially more efficient and convenient tool for clinical use.

Limitation

This study offers numerous insights, although it has several drawbacks. The cross-sectional study methodology precludes the determination of a causal association between the BRI and cognitive impairment, as the NHANES data provide a singular time point. Furthermore, while the NHANES offers a substantial and representative population sample, it may still be influenced by residual confounding from unmeasured variables, including genetic predisposition, physical activity levels, and certain dietary components. A further drawback pertains to the cognitive assessment instruments employed, despite the use of many cognitive function metrics (AFT, CERAD, and DSST scores) and the extensive categorization of cognitive impairment scores to present a thorough overview of an individual’s cognitive capabilities. However, no standard cutoff point has been used to define cognitive impairment, which may affect the applicability of our findings to different populations or settings.

Future research should employ longitudinal designs, high-quality Mendelian randomization, and genetic association analysis to ascertain a causal connection between the BRI and cognitive deterioration and focus on high-risk groups (e.g., BRI > 7.0) to validate potential associations. Furthermore, incorporating genetic markers and lifestyle factors (such as physical activity and diet) into forthcoming models may increase the understanding of the association between the BRI and cognitive health. and integrate additional established techniques for evaluating cognitive function or impairment to substantiate these connections more comprehensively.

Conclusion

This study provides preliminary evidence of a negative association between the BRI score and cognitive function and identifies a significant mediating role of depression in the association between the BRI and cognitive function. From a public health perspective, monitoring the BRI can serve as an effective tool for identifying older adults at greater likelihood of cognitive decline. By considering the BRI alongside psychological factors such as depression, more effective strategies for identifying and intervening in cognitive decline can be developed. Reducing the negative effect of central obesity on cognitive function can improve the quality of life of older adults.

Data availability

All data relevant to the study are publicly available from the NHANES website (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx).

Abbreviations

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- BRI:

-

Body roundness index

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- PIR:

-

Poverty-income ratio

- CERAD:

-

The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Word List Learning Test

- AFT:

-

Animal Fluency Test

- DSST:

-

Digit Symbol Substitution Test

- HPA:

-

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

- RCS:

-

Restricted cubic spline

- GVIF:

-

Generalized variance inflation factor

References

Guo, J. et al. Aging and Aging-Related diseases: from molecular mechanisms to interventions and treatments. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 7 (1), 391. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-01251-0 (2022).

Yang, Y., Wang, D., Hou, W. & Li, H. Cognitive decline associated with aging. In Cognitive Aging and Brain Health 25–46 (Springer, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1627-6_3.

Taylor, L., Watkins, S. L., Marshall, H., Dascombe, B. J. & Foster, J. The impact of different environmental conditions on cognitive function: A focused review. Front. Physiol. 6 https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2015.00372 (2016).

2024 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement. 20 (5), 3708–3821. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13809. (2024).

Mina, T. et al. Adiposity impacts cognitive function in Asian populations: an epidemiological and Mendelian randomization study. LANCET Reg. Health-West Pac. 33 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100710 (2023).

Nguyen, T. T., Hulme, J., Vo, T. K. & Van Vo, G. The potential crosstalk between the brain and visceral adipose tissue in Alzheimer’s development. Neurochem Res. 47 (6), 1503–1512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-022-03569-1 (2022).

Raji, C. A. et al. Visceral and subcutaneous abdominal fat predict brain volume loss at midlife in 10,001 individuals. Aging Dis. 15 (4), 1831–1842. https://doi.org/10.14336/AD.2023.0820 (2024).

Van Dyken, P. & Lacoste, B. Impact of metabolic syndrome on neuroinflammation and the Blood-Brain barrier. Front. Neurosci. 12 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00930 (2018).

Moh, M. C. et al. Association of traditional and novel measures of central obesity with cognitive performance in older Multi-Ethnic Asians with type 2 diabetes. Clin. Obes. 10 (2). https://doi.org/10.1111/cob.12352 (2020).

Nuttall, F. Q. & Body Mass Index Obesity, BMI, and health: A critical review. Nutr. Today. 50 (3), 117. https://doi.org/10.1097/NT.0000000000000092 (2015).

Janssen, I., Katzmarzyk, P. T. & Ross, R. Waist circumference and not body mass index explains Obesity-Related health Risk123. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 79 (3), 379–384. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/79.3.379 (2004).

Thomas, D. M. et al. Relationships between body roundness with body fat and visceral adipose tissue emerging from a new geometrical model. Obesity 21 (11), 2264–2271. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20408 (2013).

Zhang, X. et al. Body roundness index and All-Cause mortality among US adults. JAMA Netw. Open. 7 (6), e2415051. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.15051 (2024).

Zhan, Q. et al. Body roundness index and the risk of hypertension: A prospective cohort study in Southwest China. BMC PUBLIC. Health. 24 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-20049-z (2024).

Kawasoe, S. et al. Association between anthropometric indices and 5-Year hypertension incidence in the general Japanese population. Hypertens. Res. 47 (4), 867–876. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-023-01505-6 (2024).

Hafezi, S. G. et al. Prediction of the 10-Year incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus based on advanced anthropometric indices using machine learning methods in the Iranian population. DIABETES Res. Clin. Pract. 214 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2024.111755 (2024).

Qiu, L., Xiao, Z., Fan, B., Li, L. & Sun, G. Association of body roundness index with diabetes and prediabetes in US adults from NHANES 2007–2018: A Cross-Sectional study. LIPIDS Health Dis. 23 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02238-2 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. Non-Linear Relationship between the Body Roundness Index and Metabolic Syndrome: Data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2018. Br. J. Nutr. 131 (11), 1852–1859. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114524000357 (2024).

Jiang, N., Zhang, S., Chu, J., Yang, N. & Lu, M. Association between body roundness index and Non-Alcoholic fatty liver disease detected by fibroscan in America. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 37, 19–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.24973 (2023).

Wang, X., Guo, Z., Wang, M. & Xiang, C. Association between body roundness index and risk of osteoarthritis: A Cross-Sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. 23 (1), 334. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02324-5 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Comparison of novel and traditional anthropometric indices in Eastern-China adults: which is the best Indicator of the metabolically obese normal weight phenotype?? BMC Public. Health. 24 (1), 2192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19638-9 (2024).

Huang, S. H., Chen, S. C., Geng, J. H., Wu, D. W. & Li, C. H. Metabolic syndrome and High-Obesity-Related indices are associated with poor cognitive function in a large Taiwanese population study older than 60 years. Nutrients 14 (8), 1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14081535 (2022).

Guillemot-Legris, O., Muccioli, G. G., Obesity-Induced & Neuroinflammation Beyond the hypothalamus. TRENDS Neurosci. 40 (4), 237–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2017.02.005 (2017).

Kullmann, S. et al. Brain insulin resistance at the crossroads of metabolic and cognitive disorders in humans. Physiol. Rev. 96(4), 1169–1209. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00032.2015 (2016).

Tanaka, H., Gourley, D. D., Dekhtyar, M., Haley, A. P. & Cognition Brain structure, and brain function in individuals with obesity and related disorders. Curr. Obes. Rep. 9 (4), 544–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-020-00412-y (2020).

Lan, X. et al. The association between overweight/obesity and poor cognitive function is mediated by inflammation in patients with major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 313, 118–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.06.073 (2022).

Zuo, W. & Yang, X. A. Predictive model of cognitive impairment risk in older adults with hypertension. J. Clin. Neurosci. 133, 111032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2025.111032 (2025).

Mehta, K. et al. Depression and bone loss as risk factors for cognitive decline: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 76, 101575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2022.101575 (2022).

Milaneschi, Y., Simmons, W. K., van Rossum, E. F. C. & Penninx, B. W. Depression and obesity: evidence of shared biological mechanisms. Mol. Psychiatry. 24 (1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0017-5 (2019).

Fulton, S., Décarie-Spain, L., Fioramonti, X., Guiard, B. & Nakajima, S. The menace of obesity to depression and anxiety prevalence. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 33 (1), 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2021.10.005 (2022).

Smagula, S. F. et al. Association of 24-Hour activity pattern phenotypes with depression symptoms and cognitive performance in aging. JAMA Psychiatry. 79 (10), 1023–1031. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2573 (2022).

Jia, W. et al. Association between dietary vitamin B1 intake and cognitive function among older adults: A Cross-Sectional study. J. Transl Med. 22 (1), 165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-04969-3 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Zhang, P. & Yin, D. Association between a body shape index and cognitive impairment among US older adults from a Cross-Sectional survey of the NHANES 2011–2014. Lipids Health Dis. 23 (1), 169. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02165-2 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. The relationship between body roundness index and depression: A Cross-Sectional study using data from the National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 2011–2018. J. Affect. Disord. 361, 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.05.153 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Waist-to-Weight index and cognitive impairment: Understanding the link through depression mediation in the NHANES. J. Affect. Disord. 365, 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.08.067 (2024).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. W. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16 (9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x (2001).

Liu, L. Exploring the association between overactive bladder (OAB) and cognitive decline: mediation by depression in elderly adults, a NHANES weighted analysis. Sci. Rep. 15 (1), 3669. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86267-6 (2025).

Tingley, D., Yamamoto, T., Hirose, K., Keele, L. & Imai, K. Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 59 (5). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v059.i05 (2014).

Guo, D. et al. Relationship between body roundness index and cognitive impairment in Middle-Aged and older adults: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 17 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2025.1522989 (2025).

Huang, S. H., Chen, S. C., Geng, J. H., Wu, D. W. & Li, C. H. Metabolic syndrome and High-Obesity-Related indices are associated with poor cognitive function in a large Taiwanese population study older than 60 years. NUTRIENTS 14 (8). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14081535 (2022).

Ozato, N. et al. Association between visceral fat and brain structural changes or cognitive function. Brain Sci. 11 (8), 1036. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11081036 (2021).

Kashal, F. R. et al. The association between cognitive impairment and anthropometric indices among the elderly: Birjand longitudinal aging study. J. DIABETES Metab. Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-024-01404-8 (2024).

Ferreira Silva, M. V. et al. das G. Alzheimer’s Disease: Risk Factors and Potentially Protective Measures. J. Biomed. Sci. 26. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-019-0524-y

Huang, X., Lv, X. & Jiang, H. The Weight-Adjusted-Waist index and cognitive impairment among U.S. Older adults: A Population-Based study. Front. Endocrinol. 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1276212 (2023).

Clark, L. R. et al. Hypertension and obesity moderate the relationship between β-Amyloid and cognitive decline in midlife. Alzheimers Dement. 15 (3), 418–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.09.008 (2019).

Huang, X., Wang, Y. J. & Xiang, Y. Bidirectional communication between brain and visceral white adipose tissue: its potential impact on Alzheimer’s disease. eBioMedicine 84 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104263 (2022).

Chen, W., Johansen, V. B. I. & Legido-Quigley, C. Bridging brain insulin resistance to Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 49 (11), 939–941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2024.09.004 (2024).

Arnold, S. E. et al. Brain insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes and alzheimer disease: concepts and conundrums. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 14 (3), 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2017.185 (2018).

Hainsworth, A. H., Markus, H. S. & Schneider, J. A. Cerebral small vessel disease, hypertension, and vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia. Hypertension 81(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.123.19943 (2024).

Li, H., Ren, J., Li, Y., Wu, Q. & Wei, J. Oxidative stress: the Nexus of obesity and cognitive dysfunction in diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 14 https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1134025 (2023).

Botto, R., Callai, N., Cermelli, A., Causarano, L. & Rainero, I. Anxiety and depression in Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of pathogenetic mechanisms and relation to cognitive decline. Neurol. Sci. 43 (7), 4107–4124. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-022-06068-x (2022).

Szymkowicz, S. M., Gerlach, A. R., Homiack, D. & Taylor, W. D. Biological factors influencing depression in later life: role of aging processes and treatment implications. Transl Psychiatry. 13 (1), 160. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02464-9 (2023).

Zhang, N., Chao, J., Wu, X., Chen, H. & Bao, M. The role of cognitive function in the relationship between surrogate markers of visceral fat and depressive symptoms in general Middle-Aged and elderly population: A nationwide Population-Based study. J. Affect. Disord. 338, 581–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.06.044 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants who volunteered as part of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Funding

This study was supported by the Fudan-Yiwu Fund (FYX-23-102), the TZI-ZJU Industrial Program (2023 CLG01, 2023 CLG01PT) and the Xiangnan University 2022 Scientific Research Projects (2022 JX104).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xi Liao: Writing - original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Yongwei Li: Writing -review & editing, Writing - original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. Zongyao Zhang: Visualization, Validation, Software, Data curation. Ying Xiao: Writing - review & editing. Xi Yu: Validation, Investigation. Ran Huang: Writing - review & editing, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition. Tian Zhong: Review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

This study was conducted with publicly available NHANES data, which were collected by the CDC with ethical approval from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Research Ethics Review Board. All participants in the NHANES provided informed consent, and the procedures adhered to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Since this study involves secondary analysis of deidentified data, no further ethical approval was needed.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liao, X., Li, Y., Zhang, Z. et al. Associations of the body roundness index with cognitive function in US older adults and the mediating role of depression: a cross-sectional study from the NHANES 2011–2014. Sci Rep 15, 16884 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01383-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01383-7