Abstract

During a hailstorm in Weining County, Bijie City, Guizhou Province, on July 27, 2022, the radar echo of a strong convective monomer rapidly changed after a hail suppression operation. Using high-spatiotemporal-resolution sector-scanning data at 12-s intervals from the X-band dual-polarization phased array radar, we analyzed macro and micro changes in the monomer before and after hail suppression. We inversely analyzed the three-dimensional wind field of the monomer using phased array radar data. Within one minute, the echo height, intensity, and vertically integrated liquid water content significantly decreased. The positive radial velocity column near the operation point broke, updraft velocity and area decreased, and downdraft velocity and area increased. In the explosion-affected area, strong echo samples rapidly decreased, weak echo samples increased, the number of hail particles rapidly decreased, and number of graupel particles increased. The cloud changed rapidly within minutes after the operation, not meeting the time requirement of the catalytic theory. It was affected by the explosion. The explosion broke up large particles near the explosion point and decreased their diameter, and the dynamic disturbance generated inhibited the strong convective internal updraft, suppressing convective cloud development. The results provide some observational evidence for the explosion hail suppression theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extreme hail can be a major meteorological disaster causing serious losses in China. Artificial hail suppression is an important method of mitigating or avoiding hail hazards1,2. Since 1973, China has used 37 mm anti-hail guns for hail suppression and rain enhancement operations. Years of hail suppression practice and a large number of hail suppression field observations and tests locally and internationally have shown that artificial hail suppression is effective3,4,5,6,7,8 and that the explosion effect plays a dominant role in hail suppression1,9,10. Many researchers have explored the scientific principles underlying the explosion effect on hail clouds. Hoerner11 studied the impact of sound waves on the flow around a sphere and found that they affected the precipitation particles. Goyer12 observed the effect of a blast cable explosion on the scale distribution spectrum of water droplets emitted by a fountain and found that the explosion caused large water droplets to break and the number of small water droplets to increase. Shi et al.13 found that a shockwave generated by an explosion can accelerate the diffusion of AgI ice nuclei to achieve rapid competition for supercooled water, significantly increasing the nucleation rate. Xu et al.14. proposed that explosion turbulence and gravity wave fragmentation could inhibit the cloud airflow field and applied numerical models for simulation and test, obtaining simulation results consistent with the physical hypothesis. Duan et al.15. found, in a simulation study, that explosions break large droplets into droplet clusters smaller than 0.08 cm in diameter. The droplet fragmentation induced by the explosion inhibits the growth of large hails. Xu et al.10 systematically elaborated on the inhibition of the dynamic disturbance field generated by an explosion in the basic flow field of a cloud and the development of a strong convective cloud. However, owing to the long scanning period of the conventional weather radar observation mode (5–6 min, nine-layer elevation scanning), it is impossible to fully capture the rapid changes in clouds before and after the hail suppression operation. Evidence of hail suppression using an anti-hail gun is scarce, and the exact mechanism of action remains unknown.

In recent years, phased array radars have been gradually applied in the meteorological industry16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. Phased array weather radar has a rapid scanner and high resolution, providing equipment support for the fine detection of hail cloud evolutions and the effect of hail suppression explosions. Chen et al.22 and Liu et al.24 found that an X-band phased array weather radar system and its echo data were reliable. In a strong convective weather analysis, Yu et al.25 found that the spatiotemporal resolution of X-band phased array radar observation data is substantially higher than that of S-band dual-polarization radar data, enabling a more accurate description of the short-term evolution of supercells. Zhang et al.26 determined the change in the composite reflectivity, polarization, and wind field during the evolution of hail clouds by analyzing data from the X-band dual-polarization phased array weather radar located in Kunming City. Sun et al.27 and Dong et al.28 observed and analyzed the macro and micro-changes in hail clouds and the explosion effect before and after the hail suppression operation based on data from the X-band dual-polarization phased array radar located in Xi County, Shanxi Province. The X-band dual-polarization phased array weather radar enables the capture of rapid changes in the macro and microstructure of clouds after the hail suppression operation and the exploration of the explosion effect of the hail suppression operation. However, the X-band dual-polarization phased array weather radar is rarely used for hail cloud observations and hail suppression operation observations in Southwest China.

The Guizhou Hail Suppression Base is located in Weining County, Bijie City, Guizhou Province, at the intersection of the platform and slope transition zone of the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau, with an average altitude of 2,200 m. The hail process is characterized by typical pulse hailstorms29. In 2021, the base launched hail cloud observations and artificial hail suppression operation observation experiments with a variety of high-precision special observation equipment, such as X-band dual-polarization phased array radar. In this study, observation data with high spatiotemporal resolution of the X-band dual-polarization phased array radars, radiosonde data, hail suppression operation information, and other data from the Guizhou hail suppression base were used to analyze the evolution of the strong convective monomer during the hail process on July 27, 2022, and the macro- and micro-changes in the clouds in a short time before and after a hail suppression operation. This has provided the basis for testing the hail suppression explosion effect.

Data and methods

Data and parameters

All times in this article are in Beijing time, i.e. (UTC + 8).

Observation data generated by X-band dual-polarization phased array radars of the same model, which are products of Eastone Washon, at Xueshan Station and Xinming Station of the Guizhou Hail Suppression Base, were mainly used in this study. Supplementary Table S1 lists the radar parameters used in this study. Radar uses three-dimensional and sector-scanning detection modes. In the three-dimensional detection mode, data were scanned every 60 s. Meanwhile, in the sector-scanning detection mode, data were scanned every 12 s with an observation range of 120–190° in azimuth. Sixty-four elevations with a sampling resolution of 1.125° were used for data scanning. Each elevation contained approximately 240 orientations with a sampling resolution of 1.5°. The radial range resolution was 30 m, and the maximum detection range was 45 km. The Xueshan radar uses the sector-scanning detection mode (120–190°) from 13:04:57 to 13:07:13, generating a total of 12 sector-scanning data, and the three-dimensional detection mode for the rest of the time. The Xinming radar used a three-dimensional detection mode throughout the process.

To improve data quality, we processed the X-band dual-polarization phased array radar observation data through ground clutter filtering, attenuation correction, KDP calculation, and other quality control methods30,31,32,33,34,35. We compared the intensity and location of the phased array radar echo with the radar data of network deployment services in Zhaotong City, Yunnan Province, which is closest to the base. The C-band Doppler weather radar with a radial range resolution of 0.1 km and detection radius of 150 km in Zhaotong City (Zhaotong radar) is a CINRAD-CC single-polarization radar, approximately 49 km from the Xueshan radar and 47 km from the Xinming radar, generating nine-layer scanning observation data every 6 min (Fig. 1). The echo intensity and location of the X-band dual-polarization phased array radars were consistent with those of the Zhaotong radar (Supplementary Figure S1).

The map in Fig. 1 was created using ArcGIS Desktop (version 10.8, available at https://desktop.arcgis.com/).

Physical quantities and products closely related to the physical characteristics of hail clouds and hail falls were selected for our analysis, including the reflectivity factor (dBZ), Doppler radial velocity (vel, m/s), composite reflectivity (CR, dBZ), vertically integrated liquid water content (VIL, kg/m2), echo top height with different intensity thresholds (km), echo area ( km2), particle phase identification products, and three-dimensional wind field inversion products.

Composite reflectivity (CR) and vertically integrated liquid water content (VIL) require additional calculations27,36. In addition, we used the phase identification method proposed by Wu et al.37, which is based on the HCA algorithm, to obtain ten types of phase particles through fuzzy logic operation and weight value calculation, including ground clutter or anomaly propagation (GC/AP), biological echoes (BS), dry snow (DS), wet snow (WS), crystal (CRY), graupel (GR), big drop (BD), rain (RA), heavy rain (HR), and rain and hail (RH). We also used the three-dimensional variational data assimilation (3DVAR) wind field inversion method38,39,40,41 to obtain the three-dimensional wind field by inversing the radial velocity of the Xueshan Radar and the Xinming Radar, two X-band dual-polarization phased array radars.

Research methods

The target cloud consisted of an independent monomer. By comparing and analyzing the changes in the radar parameters, particle phase state, and internal airflow field of the convective cloud and explosion-affected area in a short time before and after a hail suppression operation, we examined the effect of an anti-hail gun operation explosion on the macro and microstructure of the cloud.

Definition of the target monomer

Echoes greater than or equal to 18 dBZ for the target cloud were included in the analysis range of convective clouds. In the later period, there was a new convective monomer on the left side of the cloud, and the target monomer merged with its 30 dBZ echo at 13:02. The strong echo center remained independent, so the two clouds were divided by the 45 dBZ echo in the later period (box marked a in Fig. 2).

Definition of the explosion-affected area

The hail-suppression operation was a fixed-point operation, using the customized 37 mm Anti-hail Gun XIII of Chongqing 152 Factory; the self-detonation time of the fuse was approximately 16 s, the operation azimuth was 290°, and the elevation was 55°. Based on the ballistic trajectory formula, the theoretical location of the explosion point of the anti-hail gun ammunition was calculated at the Xueshan radar’s azimuth of 152.05°, a horizontal distance of 12.37 km from the radar, 4.254 km above the ground, which was 104.147°E and 26.954°N in longitude and latitude, and 6.763 km above sea level (the Xueshan radar was 2.509 km above sea level). Considering the anti-hail gun muzzle vibration and explosion point deviation during the operation, the 400 m range area around the explosion point was considered as the explosion-affected area (box marked b in Fig. 2).

Weather background

At 08:00 on July 27, 2022, the Eurasian mid–high latitudes at 500 hPa showed two ridges and one trough. The middle and low latitudes showed multiple short-wave trough activities, and the Guizhou region at 700 hPa was controlled by southwest winds, with significant wind convergence in the Zhaotong Weining area, which formed suitable dynamic conditions for convection. At 12:00, a low trough formed on the northwestern edge of Guizhou at 500 hPa, affecting Weining. Here, the convective available potential energy was strong, reaching 1200 J/kg, and the atmospheric precipitable water was 30–40 kg/m2, with abundant concentrated water vapor content and a negative vertical integral of the divergence of water vapor flux. The surface convergence line pressed south to the middle line of Bijie, with easy-to-trigger convection. The radiosonde data of Weining Station at 08:00 showed that the atmospheric wet layer was shallow and concentrated below 550 hPa. The humidity condition of the lower layers was suitable, with prominent dry layers amid the middle and upper layers. The atmosphere was dry at the top and wet at the bottom. The altitude of the 0 °C layer was 5.173 km (height above sea level), 6.954 km for the − 10 °C layer, and 8.776 km for the − 20 °C layer. Generally, the weather conditions and atmospheric environment of the day are conducive to the formation and development of hail weather. According to the actual monitoring data, from 13:00 to 16:00 that day, five spots of hail were observed in the eastern and northern areas of Weining County, with a maximum hail size of 8 mm and density of 500 particles /m2.

Process

According to the observation data from the Xinming radar, at 12:00 on July 27, the target cells gradually developed and hail suppression operations were carried out at 13:05, after which the cloud body weakened rapidly (Figs. 2 and 3). At 12:50, the incipient convective echo was suspended in the air. The echo was located at a height of 3–6.6 km from the ground with a maximum intensity of 25 dBZ, and then extended upward and downward, and rapidly intensified. At 12:55, the echo intensity of the monomer reached 45 dBZ, and the echo profile was fusiform with a broad upper and narrow bottom. At 13:02, the echo intensity reached 60 dBZ, with the echo top height exceeding 9 km (Fig. 3, a ~ d). This echo-development law is consistent with the results of Dong et al.29. The echo moved slowly east to the north at a velocity of approximately 14.6 km/h. From 13:05:40 to 13:06:10, the Xiaohai Station carried out the hail-suppression operation at an azimuth of 290° and an elevation of 55°. This was a fixed-point operation that used 43 rounds of ammunition. Based on the calculation of the explosion point of the anti-hail gun ammunition using the ballistic trajectory formula (Figs. 2 and 3f), the explosion point was in the strong central area of the echo, the upper end of the 45 dBZ strong echo column, and near the − 10 °C layer, which is appropriate. After operation, the strong center of the cloud splits, gradually weakens, and dissipates (Fig. 3,e ~ h).

Based on the statistics of the convective cloud radar parameters, we calculated the CR, VIL, and echo top height at different intensities. It can be seen from the changes in the CR and VIL over time (Fig. 4a) that the incipient convection developed rapidly. The echo intensity and VIL peaked after 9 and 15 min, respectively. The maximum echo intensity was 62 dBZ and the maximum VIL was 20.31 kg/m2. The VIL rapidly increased from 4.15 to 19.16 kg/m2 during 12:59–13:04:57. As the VIL surge is an identification indicator of hail clouds42,43,44, the monomer may develop into a hail cloud. The strong convective monomer was in the developing stage during the operation, which can be seen from the changes in the echo tops with different intensities over time (Fig. 4b). At 12:55, the height of the 45 dBZ echo top (H45dBZ) was 3–4 km, and that of echoes of different intensities continued to increase. At 13:04, the height of the 18 dBZ echo top (H18dBZ) reached 10 km, while H45dBZ reached 7 km. Both remained unchanged, indicating that convective clouds developed vigorously in a mature stage. At 13:05:40, the operation was carried out. Subsequently, VIL, H18dBZ, and H45dBZ rapidly decreased, but CR did not change significantly in a short time. To further explore the changes in the convective cloud in a short time after the operation, the 13:04:57–13:07:13 high-spatiotemporal-resolution sector-scanning data of the Xueshan radar were used to analyze the effect of the hail suppression operation.

Macro and Micro changes in the cloud before and after the operation

Changes in macroscopic characteristics of the radar echo before and after the operation

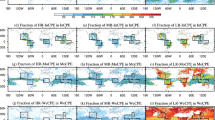

The changes in the reflectivity factor at a height of 2.93–5.86 km were compared and analyzed by layers (approximately 0.48 km) at 13:05:09 (1 min before the operation) and 13:06:23 (within 1 min after the operation; Fig. 5a). Figures 5a shows that, at a height of 2.93–3.41 km, the echo area of 45 dBZ and above changed little, decreasing by 1.8 km2 on average. At a height of 3.89–4.85 km, the strong 45-dBZ and above echo area decreased significantly, by 2.7 km2 on average. At a height of 5.33–5.86 km, the string of 45-dBZ echoes disappeared, and the monomer became loose. The H45dBZ decreased by approximately 0.48 km. This phenomenon was consistent with that reported by Yue et al.45.

Echo statistics of different altitudes and explosion affected areas before and after the operation.(a: 45 dBZ and above echo area of the monomer. The arrow indicates the change slope, with black for lower layers, red for operation-affected layers, and blue for higher layers. b: the sample numbers of echoes with different intensities in the explosion area).

The explosion height was approximately 4.254 km. The explosion broke up large droplets nearby, reducing their diameter15. These were also rapidly dispersed near the explosion point and collided with the surrounding frozen droplets, reducing their average mass and diameter46. This inhibited the development of clouds near the explosion point, leading to a rapid reduction in echo intensity and a strong echo area at the 3.90–4.88 km altitude layer. The explosion force inhibited the strong convective internal updraft47, resulting in a decrease in the strong center height of the cloud. As the effect of shock waves on the airflow is not instantaneous, the change in echo in the 4.88–5.86 km layer was slower than that in the 3.90–4.88 km layer.

We then selected the range-height indicator (RHI) data in the range of the operation azimuth. Considering the movement of the cloud, the radar azimuth was selected as 152.05–151.6° to analyze the vertical structure of the convective cloud (Fig. 3,e ~ h). The section view before the operation (13:04:57) shows that the center of the strong monomer echo was approximately 11 km away from the radar, reaching 60 dBZ. The echo top height was 8 km, and the H45dBZ was 6.08 km, close to the − 20 °C layer height at approximately 6.267 km. After the operation, H45dBZ rapidly dropped to 4.5 km.

Based on a statistical analysis of the changes in the sample size of echoes with different intensities in the explosion-affected area before and after the operation over time (Fig. 5b), we found that: 1 min before the operation, the echo intensity in the area was concentrated in the range of 46–51 dBZ, with a maximum echo intensity of 53 dBZ; more than 40 echo samples were in the range of 47–49 dBZ, and more than 15 were in the range of 46–51 dBZ; 1 min after the operation, strong echoes of ≥ 50 dBZ decreased rapidly, weak echoes of 40–45 dBZ increased rapidly, and echo intensity was in the range of 43–47 dBZ, with the maximum echo intensity decreasing to 48 dBZ. These results are consistent with those reported by Dong et al.28. The explosion suppressed the strong echoes, the echo intensity in the explosion-affected area after the operation weakened rapidly, and the volume of the strong echoes decreased rapidly to transform into weak echoes. This resulted in an increase in weak echoes, further proving that the explosion broke the large particles nearby and reduced their diameter, leading to a rapid reduction in the strong echo samples and an increase in the weak echo samples.

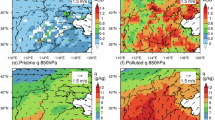

Changes in the cloud dynamic field before and after the operation

According to the radial velocity variation diagram (Fig. 6), the distribution of velocity in the top layer changed from negative to positive before hail suppression operation, corresponding to the divergence characteristics in the top layer( (Fig. 6a). There was a completely positive velocity column from the bottom to the upper layer below the divergence area, indicating a strong updraft in the cloud. This was conducive to the upward transport of water vapor in the lower layer. After operation, the lower positive velocity column near the explosion point broke, indicating that the explosion force inhibited the development of the updraft near the explosion point.

The profile was along the moving direction of the cloud. The three-dimensional wind field profile (Fig. 7) showed that, before the operation, there was a strong updraft above the strong echoes, and the bottom of the updraft reached 3.12 km, with a weak downdraft at lower layers, indicating that the cloud was vigorously developing. The operation point is located in the main upward airflow area. Within 1 min after the operation, the updraft weakened, the cloud top above the operation point collapsed (30 dBZ above echoes moved downward), the operation point area became a downdraft airflow, and the upward airflow area was lifted to above the operation point, the bottom of the updraft rose to 5 km, and the downdraft area and wind speed increased in the middle and lower levels. The updraft field in the cloud was destroyed after the operation, further proving the inhibitory effect of the explosion force on the updraft in the cloud.

Differences in hydrocondensate phase identification before and after the operation

According to the hydrocondensate phase identification variation diagram (Fig. 8a), before the operation, there were many graupel particles and ice crystals above the core 0 °C layer of the convective cloud and a small amount of RH between the 0 and − 10 °C layers. From the bottom of the 0 °C layer to the ground, there was rain (RA), HR, rain and hail (RH) from the outside, and a small amount of DS and WS near the 0 °C layer, indicating that the ice-phase particles partially melted during the fall. The explosion-affected area was located above the hail column in a cloud. After the operation, the hail column beneath the explosion area broke, and the RH areas in the air dispersed as the area decreased. After 1 min, the hail particles beneath the explosion area disappeared. Possible causes of these phenomena include the explosion breaking up the hail particles in nearby areas, reducing their size, and the explosion also accelerating the falling speed of the particles beneath the explosion point48. This led to a rapid reduction in the number of hail particles beneath the explosion point. The fragmentation effect of the explosion reduced the particle size and changed the trajectory of the hail embryo to leave the main updraft, thus inhibiting the growth of particles15. This resulted in the disappearance of hail after the operation and no new hail particles. The explosion force also inhibited the updraft beneath the explosion point, causing the top height of the graupel particle layer to decrease.

Figure8b presents the statistics of the sample numbers of hydrocondensate particles in the explosion-affected area before and after the operation. Two minutes before the operation, there was a large amount of graupel (GR) and small amounts of HR and RH in this area. Before the operation (13:05:16), the number of hail particles increased, while that of graupel particles decreased. During the operation, the number of hail particles fluctuated and increased, and then rapidly decreased. The change in the number of graupel particles was contrary to that of the hail particles, further proving that the explosion caused large particles (hail) in nearby areas to break up and the particle diameter to decrease.

Summary

Based on the high-spatiotemporal-resolution scanning data of X-band dual-polarization phased array radars, in this study, we examined the development and evolution of strong convective cloud monomers and the macro- and micro-changes in the cloud in a short period before and after the hail-suppression operation by analyzing the operation of a strong convective monomer in Weining County on July 27, 2022, providing a basis for subsequent studies on hail clouds and the explosion effect of artificial hail suppression in plateau mountains at middle and low latitudes. The main conclusions are as follows.

Incipient echoes of weak strong convective monomers were generated from the air and extended upward and downward. They developed rapidly, with echo intensity growing from 20 to 50 dBZ in just 12 min, but moved slowly at approximately 14.6 km/h. The maximum echo intensity of the cloud reached 60 dBZ, with H45dBZ exceeding the height of the − 10 °C layer. The VIL surged, indicating the possibility of a hailfall.

Within 1 min after the operation, the explosion caused the nearby large droplets to break up and the diameter to reduce, resulting in a rapid reduction in echo intensity and a strong echo area at an operation height of 3.90–4.88 km, and a decrease in VIL of 3 kg/m2. The explosion force suppressed the strong convective internal updraft, reducing the strong center height of the cloud, with H45dBZ dropping approximately 0.48 km. In the explosion-affected area, the maximum echo intensity decreased by 5 dBZ, the strong echo samples of ≥ 50 dBZ decreased rapidly, and the weak echo samples of < 45 dBZ increased. The explosion suppressed strong echoes.

The positive radial velocity column near the explosion point was broken after the operation. The three-dimensional wind field structure in the cloud showed that, after the operation, the updraft was weakened, the bottom of the updraft rose by approximately 2 km, the area of the downdraft at the middle and lower layers increased, and the wind speed increased. This explosion inhibited cloud updrafts.

According to the difference in phase identification of hydrocondensate particles before and after the operation, after the operation, the hail column beneath the explosion area broke, the hail area above the 0 °C layer decreased until it disappeared, and the top height of the graupel particle layer decreased. According to the statistics on the sample numbers of hydrocondensate particles in the explosion-affected area, the number of hail particle samples decreased rapidly 13 s after the operation. Meanwhile, the number of graupel particles increased rapidly, further proving that the explosion caused the fragmentation of large particles (hail) in the nearby area and reduced the particle size.

The main aim of the present study was to test and demonstrate the mechanism of hail suppression in the early stage based on observation. In the present study, the scanning frequency of the X-band dual-polarization phased array radars was set at 13–60 s, enabling clear observation of the rapid development and evolution of strong convective clouds from birth to maturity and capture of the rapid changes of macro- and micro-radar of the cloud after operation, demonstrating the advantages of phased array radar in meteorological observations of hail and other strong convective weather. In this study, the effect of the explosion on clouds is verified by the observed data, that is, the explosion broke the large droplets nearby with a rapid decrease in their diameter. The explosion force suppressed the strong convective internal updraft, leading to a reduction in the strong center height of the cloud. However, the effect of the shock wave on the airflow was not instantaneous, and the upper layers of the cloud changed more slowly. In the present study, we analyzed only one hail suppression process. More processes need to be statistically analyzed in future research to establish a common pattern.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Huang, M. Y., Xu, H. Y. & Zhou, L. .40 year’s hail suppression in China. Clim. Environ. Res. 5, 318–328 (2000).

Lei, H. C., Hong, Y. C., Zhao, Z., Xiao, H. & Guo, X. L. Advances in cloud and precipitation physics and weather modification in recent years. Chin. J. Atmos. Sci. 32, 967–974 (2008).

Huang, M. Y. Introduction To Artificial Hail Suppression and Basic Knowledge of Artificial Precipitation and Hail Suppression223–235 (China Meteorological Press, 1974).

Huang, M. Y. & Wang, A. S. Introduction To Artificial Hail Suppression (Science, 1980).

Mesinger, F. & Mesinger, N. Has hail suppression in Eastern Yugoslavia led to a reduction in the frequency of hail? J. Appl. Meteor. 31, 104–111 (1992).

Liang, G., Yue, Z. G., Li, Y. & Tian, X. A field experiment of ‘gun and rain fall’. J. Shaanxi Meteorol. 25–28 (2009).

Gilbert, D. B., Boe, B. A. & Krauss, T. W. B. A. Twenty Seasons of Airborne Hail Suppression In Alberta, Canada. JournalWeaMod 48, 68–92 (2016).

Yao, Z. Y. et al. Review of advances in hail formation process and hail suppression research. Acta Meteorol. Sin 80, 835–863 (2022).

Xu, H. B. & Wang, S. W. A study on the theoretical bases and technological gists for hail suppression by explosion. J. Appl. Meteorol. Sci. 311–318 (1989).

Xu, H. B. The practice and theory of hail suppression in China (China Meteorological Press, 2021).

Hoerner, S. Tests of spheres with reference to reynolds number, turbulence, and surface roughness (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, 1935).

Goyer, G. G. Mechanical effects of a simulated lightning discharge on the water droplets of ‘old faithful’ geyser. Nature 206, 1302–1304 (1965).

Shi, A. Y. & Fan, H. X. Experimental study on AgI ice nucleation efficiency of the 37-mm anti-hail gun. Chin. J. Atmos. Sci. 6, 315–323 (1982).

Xu, H. B. The possible dynamic mechanism of explosion in hail suppression. Acta Meteorol. Sin. 59, 66–76 (2001).

Duan, Y. & Xu, H. B. The possible cloud-micro physical mechanism of explosion in hail suppression. Acta Meteorol. Sin. 56, 334–340 (2001).

Witt, A. et al. Rapid-scan radar observations of an Oklahoma tornadic hailstorm producing giant hail. Weather Forecast. 33, 1263–1282 (2018).

Ma, S. Q. et al. Design and initial implementation of array weather radar. J. Appl. Meteorol. Sci. 30, 1–12 (2019).

Fu, P. L., Hu, D. M., Huang, H., Zhang, Y. & Tian, C. C. Observation of a tornado event in outside-region of typhoon Mangkhut by X-band polarimetric phased array radar in 2018. J. Appl. Meteorol. Sci. 31, 706–718 (2020).

Liu, Y. & Zhang, T. Analysis of the characteristics of X-band dual-polarization and phased-array weather radar during a hail weather process in early spring. Adv. Geosci. 11, 1188–1194 (2021).

Moroda, Y. et al. Lightning bubbles caused by upward reflectivity pulses above precipitation cores of a thundercloud. Sola 18, 110–115 (2022).

Morotomi, K. & Shimamura, S. Observation of a tornado using phased array weather radar. Wind Eng. JAWE 47, 134–138 (2022).

Chen, Y. H. et al. The Guangzhou phased-array radar networking scheme set-up and observation test. Meteorol. Mon. 46, 823–836 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. The hazardous convective storm monitoring of phased-array antenna radar at Daxing international airport of Beijing. J. Appl. Meteorol. Sci. 33, 192–204 (2022).

Liu, J., Huang, X. Y., He, Y. Q., Wang, Z. H. & Wang, J. H. Comparative analysis of X-band phased array antenna weather radar measurements. Plateau Meteorol. 34, 1167–1176 (2015).

Yu, M. H., Liu, L. P., Wu, C. & Xiao, Y. J. Analysis of severe convective process in South China on 3 June 2016 using phased-array and dual-polarization radar. Meteorol. Mon. 45, 330–344 (2019).

Zhang, T. et al. Analysis of phased array radar characteristics of a hail process in the Southwest low latitude plateau. J. Catastrophology. 38, 89–93 (2023).

Sun, Y. et al. Features of phased-array dual polarization radar observation during an anti-aircraft gun hail suppression operation. J. Appl. Meteorol. Sci. 34, 65–77 (2023).

Dong, Y. N., Liu, F. X., Sun, H. P. & Yang, Y. L. A study on dynamic effect of hail suppression by anti-hail gun with phased array radar. Meteorol. Mon. 49, 995–1004 (2023).

Dong, Y., Hua, S. F., Chen, B. J., Wang, H. & Hou, T. J. Numerical simulation of a pulse hailstorm in the plateau region in Southwestern China J. Atmos. Res. 299 (2024).

Liu, L. P., Wu, L. L. & Yang, Y. M. Development of fuzzy-logical two-step ground clutter detection algorithm. Acta Meteorol. Sin. 65, 252–260 (2007).

Wang, Y. & Chandrasekar, V. Algorithm for estimation of the specific differential phase. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 26, 2565–2578 (2009).

Wu, H. & Huang, X. Y. Schemes for Attenuation correction of radar reflectivity factor, ground clutter discrimination and compensation of a X-band dual-polarization radar. J. Meteorol. Sci. 34, 32–38 (2014).

Wu, W., Zhou, Y. J., Li, X. M. & Zhai, L. Comparative study on quality control methods of X-band dual-polarization radar data. J. Chengdu Univ. Inf. Technol. 32, 19–27 (2017).

Li, Z. F., Xiao, H., Feng, L. & Chen, K. H. Method of Attenuation correction and effect test of X-band dual-polarization weather radar. Meteorol. Sci. Technol. 47, 731–739 (2019).

Xiao, L. S. et al. Study on Attenuation correction algorithm of X-band dual-polarization phased array radar. Meteorol. Mon. 47, 703–716 (2021).

Diao, X. G., Zhu, J. J., Huang, X. Z., Yang, C. F. & Liu, Z. H. Gen, L. Application of VIL and VIL density to hail cloud criterion. Plateau Meteorol. 27, 1131–1139 (2008).

Wu, C., Liu, L. P., Yang, M. L., Ma, J. L. & Li, J. Key technologies of hydrometeor classification and mosaic algorithm for X-band polarimetric radar. J. Appl. Meteorol. Sci. 32, 17 (2021).

Shapiro, A., Potvin, C. K. & Gao, J. Use of a vertical vorticity equation in variational dual-Doppler wind analysis. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 26, 2089–2106 (2009).

Potvin, C. K., Shapiro, A. & Xue, M. Impact of a vertical vorticity constraint in variational dual-Doppler wind analysis: Tests with real and simulated supercell data. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 29, 32–49 (2011).

North, K. W. et al. Vertical air motion retrievals in deep convective clouds using the ARM scanning radar network in Oklahoma during MC3E. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 10, 2785–2806 (2017).

Li, Y., Ma, S. Q., Yang, L., Zhen, X. Q. & Qiao, D. Wind field verification for array weather radar at Changsha airport. J. Appl. Meteorol. Sci. 31, 1–12 (2020).

Liu, Z. G., Tao, J. H., Yang, J. C., Fu, Z. & Liang, H. H. Contrast analyses on variation characters of vertically integrated liquid water content about hail cloud cell and thundercloud cell. Plateau Meteorol. 27, 1363–1374 (2008).

Wu, J. K. & Yu, X. D. Review of detection and warning methods for sever hail events by doppler weather radars. Arid Meteorol. 27, 197–205 (2009).

Zhou, Y. S., Zhou, M. F. & Yuan, Y. Reduction characteristics of doppler radar products in mountainous areas of Guizhou. J. Guizhou Meteorol. 36, 40–43 (2012).

Liu, Z. G. et al. Effect analysis of a hail suppression by anti-hail gun based on CINRAD/CC products. Arid Meteorol. 24, 23–30 (2006).

Huang, Y. & Xu, H. Y. Numerical experiments on hail suppression by AgI seeding. Chin. J. Atmos. Sci. 18, 612–622 (1994).

Xu, H. On the mechanical effect of explosion on air flow. Meteorol. Mon. 10, 26–28 (1979).

Xu, H. B. & Wang, S. W. The effect of acoustic vibration on the boundary layer and motion state of spherical precipitation particles. Acta Meteorol. Sin. 42, 431–439 (1984).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate all the data provided by each open database. The authors thank the anonymous reviewers and academic editors for their comments.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Project (42475208), Open Project of the Key Open Laboratory of Cloud Physical Environment, China Meteorological Administration (2021Z00724), Guizhou Science and Technology Program Project (General 200 of Qiankehe Fundamental-ZK [2023], General 194 of Qiankehe Support [2023], General 246 of Qiankehe Fundamental-ZK [2022], General 193 of Qiankehe Support [2023], and General 217 of Qiankehe Fundamental-ZK [2021]), Experimental Research on Hail Suppression Technology in Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau (ZQC-24447), the CMA Key Innovation Team Project (CMA2022ZD10), Innovation Fund Project of the Key Open Laboratory of Cloud Precipitation Physics and Weather Modification, China Meteorological Administration(2023CPML-B09), Open Research Project of CMA-CUIT Joint Research Center for Weather Modification (2023GDRY017), and the Project of the CMA Weather Modification Center “Research on Hail Cloud Monitoring & Identification Technology and Hail Suppression Effect Evaluation in Guizhou Field Experiments”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W. and H. L. ; methodology, H.W. and H.L.; software, D.L. and Z.Y.; validation, H.W. and H.L.; formal analysis, H.L. and X.L.; investigation, Y.H. and Y.P.; resources, L.Y.; data curation, T.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L.; writing—review and editing, H.W. and H.L.; visualization, H.L, X.L., and S.Z. ; supervision, H.W.; project administration, H.W. and H.L.; funding acquisition, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Wang, H., Lin, D. et al. Examining the explosion effect of hail suppression operation using phased array radar observation data. Sci Rep 15, 16826 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01388-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01388-2