Abstract

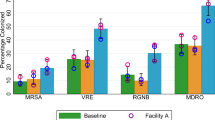

Multidrug-resistant organism (MDRO) infections pose significant challenges in intensive care settings. This prospective study aimed to evaluate the impact of a Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound (SMART) infection control plan on MDRO prevention among healthcare workers in an emergency intensive care unit (ICU). Fifty healthcare workers participated, and pre- and post-intervention assessments were conducted to measure changes in MDRO prevention indicators. Following implementation of the SMART-based plan, there was a statistically significant improvement in staff knowledge (p < 0.05), with increased hand hygiene compliance (72.1–94.2%) and isolation gown use (60.2–87.6%). MDRO infection rates decreased from 8.0 to 5.1% post-intervention (p = 0.027). These findings demonstrate the effectiveness of the SMART-based infection control plan in reducing MDRO infection rates and improving staff compliance in the emergency ICU setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) represent a significant challenge in healthcare settings, particularly in intensive care units (ICUs), where patients are at a higher risk for infections due to their critical conditions and invasive procedures1. MDRO infections not only increase morbidity and mortality rates but also extend hospital stays and healthcare costs. Effective infection control measures are essential to mitigate these risks and improve patient outcomes2. The concept of standard precautions was proposed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1995 as a new hospital infection prevention and control strategy based on universal precautions3. The core contents of standard prevention include hand hygiene, personal protective equipment, environmental cleaning and disinfection, patient placement, safe injection, etc. Standard prevention is recognized as an advanced concept for preventing and controlling hospital infections both domestically and internationally. At the same time, standard precautions also play a crucial role in preventing and controlling MDRO infections.

The SMART(Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound) principle was proposed firstly by the renowned management guru Peter Drucker’s book(The Practice of Management) in 1954. After years of development, it has been widely applied and promoted in various industries, such as medical industry4. In the SMART principle, goal setting follows specific (S), measurable (M), achievable (A), relevant (R) and time-bound (T) original. At present, the SMART principle is mainly used for infection prevention and control in the medical industry. Related studies have shown that the application of SMART principles to infection control practices aims to create clear, achievable, and timely goals that can lead to significant improvements in compliance and outcomes5,6,7.

This study aims to evaluate the impact of a SMART-based infection control plan on MDRO prevention among healthcare workers in an emergency ICU. We hypothesized that the implementation of a structured and goal-oriented plan would lead to improved knowledge, adherence to infection control practices, and reduced MDRO infection rates.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This prospective study was conducted in the emergency ICU of a tertiary care hospital. A total of 50 healthcare workers, including doctors and nurses, participated in the study. The participants were aged between 22 and 52 years, with a mean age of (34.78 ± 6.34) years. The demographic characteristics of the participants are detailed in Table 1.This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki, receiving ethical clearance from the ethics committee of Henan Provincial People’s Hospital (number: 2022 New Technology (195)). Before completing the questionnaire, all healthcare workers gave their informed consent.

Intervention

Formation of the infection control target management group

To reduce the incidence of MDRO infections and prevent MDRO infection outbreaks in the EICU, an Infection Control Target Management Group was established. The group consists of eight members: one EICU department director, one head nurse, one quality control staff from the hospital’s infection management department, one EICU infection control doctor, one EICU infection control nurse, and three nursing team leaders. Each member has more than five years of ICU work experience.

Developing an infection control plan based on SMART principles

The Infection Control Target Management Group members conducted a retrospective analysis of MDRO infections in the EICU from January to June 2023. Combining clinical practice with the SMART principles (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, Time-bound), they developed the infection control plan. Details are as follows:

Specific (S): The goal of the infection control plan must be specific and clear, facilitating execution. The goal is to improve healthcare workers’ compliance with hand hygiene and their knowledge of infection prevention and control, thereby reducing the incidence of MDRO infections and preventing outbreaks. This plan is guided by standards such as the “Hand Hygiene Standards for Healthcare Workers (WS/T313-2019)8,” WHO’s “Five Moments for Hand Hygiene9,” and the “Chinese Expert Consensus on Prevention and Control of Hospital Infections by MDROs10.” The plan is patient-centered and oriented towards clinical healthcare providers, focusing on safety, risk management, and medical quality management. The Health Failure Mode and Effect Analysis (HFMEA) model is used for prospective assessment to identify high-risk areas and influencing factors in the infection control process11. Relevant systems and processes are reviewed to provide a basis for designing infection control procedures, continuously improving and optimizing these processes, enhancing the management of hospital infection monitoring, and ultimately achieving the set goals.

Measurable (M): Infection control objectives must be measurable. Indicators are used as measurement standards, forming a system to monitor process metrics (knowledge of MDRO infection prevention and control, compliance with wearing isolation gowns when contacting MDRO patients and their environments, and the correctness of wearing isolation gowns) and outcome metrics (MDRO infection rate). This system evaluates whether the improvement plan meets the expected goals, summarizing experiences and lessons in a timely manner, optimizing implementation processes, and reinforcing plan execution.

Attainable (A): The goal of the infection control plan must be attainable. Based on the “Chinese Expert Consensus on Prevention and Control of Hospital Infections by MDROs” and hand hygiene standards, a series of feasible quality improvement measures are developed. Strengthening hand hygiene management is highlighted: WHO’s multi-modal strategy for MDRO prevention states that hand hygiene is the most important and cost-effective measure to prevent hospital-acquired infections and MDRO infections12. Ensuring the accessibility of hand hygiene facilities is fundamental. Hand sanitizers are placed at the foot of the bed, on treatment trolleys, beside medication trolleys, and at ward entrances to enhance hand hygiene compliance. Additionally, sensor-operated faucets, hand soap, and paper towels are provided to avoid recontamination during hand washing13. Hand hygiene management also includes regular inspections and feedback to genuinely improve compliance and accuracy among healthcare workers, such as hand hygiene day knowledge competitions and public education campaigns, are organized to raise awareness and skills related to hand hygiene among healthcare workers. Isolation precautions are reinforced: MDRO-infected or colonized patients are ideally isolated in single rooms with prominent blue isolation signs and notices, and all healthcare personnel are informed to limit access14. When single rooms are unavailable, patients with the same MDRO infection or colonization are grouped together, avoiding rooming with patients with indwelling catheters, open wounds, or weakened immune systems. Fixed diagnostic and treatment equipment is designated for each isolation room, ensuring dedicated use and routine cleaning and disinfection per shift. Standard precautions are taken during patient care and handling. When performing aerosol-generating procedures, working in environments with contaminated burn wounds, or handling secretions, pressure sores, drainage wounds, excreta, and stoma tubes, gloves and isolation gowns are used. Environmental and equipment cleaning and disinfection are also emphasized: following the principle of cleaning before disinfection, shared medical devices like bedside ECG machines, ultrasound machines, and suction machines are disinfected after each use15. Cleaning items like cloths, mops, and floor rags are used separately in each room. Waste generated by MDRO-infected or colonized patients is treated as medical waste, sealed with an additional yellow medical waste bag. Infectious linens are collected at the patient’s bedside in sealed containers and sent for laundering in orange-red “water-soluble anti-infection medical bags.” Terminal disinfection is strictly performed after patient discharge or transfer. If MDROs are detected on environmental surfaces, the cleaning and disinfection frequency is increased. MDRO infection prevention and control training is intensified: WHO guidelines strongly recommend combining bundled MDRO infection control measures with quality improvement or educational interventions to reduce device-associated infections16. ICU staff must receive regular training and education on infection control. This plan involves mandatory training for all staff, including caregivers, with increased training frequency. Participation and assessment in these trainings are included in staff performance evaluations.

Relevant (R): The goal of the infection control plan should be closely related to relevant guidelines, standards, systems, and processes. During the implementation of the quality improvement plan, recommendations from domestic and international guidelines are referenced, integrating related international review standards and expert consensus. This shifts the traditional approach to MDRO infection prevention and control by focusing on systems, training, and projects. By advancing infection prevention measures such as hand hygiene, contact isolation, continuous infection control training, and effective feedback and supervision, potential hazards are proactively identified and eliminated. The effectiveness and efficiency of the plan are enhanced by using monitoring data on hand hygiene compliance, hand hygiene success rates, and infection rates as benchmarks.

Time-bound (T): The goal of the infection control plan must be time-bound, with regular checks on the progress of the plan and timely assessments of goal achievement. Under the organization of the Infection Control Target Management Group, monthly quality control meetings are held in the ward to summarize and analyze MDRO infection situations, report healthcare workers’ hand hygiene compliance, hand hygiene success rates, and compliance with contact isolation. Quarterly ward meetings are held to report on MDRO infection prevention and control efforts.

Implementation of the infection control plan

Under the guidance of the Infection Control Target Management Group, the infection control plan was implemented in the emergency ICU from July to December 2023. The department head and head nurse supervised the implementation of the plan, while other group members provided guidance and solutions to any issues arising during the implementation process.

Collection of infection control indicators

Indicators such as MDRO infection control knowledge awareness, hand hygiene compliance rate, isolation gown usage compliance rate, and MDRO infection rate in the emergency ICU were collected and compared before (January to June 2023) and after (July to December 2023) the intervention among 50 healthcare workers.

MDRO Infection Control Knowledge Awareness: The infection control doctor and nurse in the group jointly prepared an MDRO infection control knowledge test with 50 single-choice questions, scoring 100 points in total. The test was administered anonymously online to 52 healthcare workers before and after the implementation of the SMART goal management plan to assess their awareness of MDRO infection control knowledge.

Hand Hygiene Compliance Rate: Using the hand hygiene compliance inspection form from the hospital infection management manual issued by the hospital’s infection management department, the infection control nurse in the group randomly checked the hand hygiene compliance of 50 healthcare workers in the emergency ICU before and after the implementation of the SMART goal management plan. This form is designed based on the WHO’s five moments for hand hygiene, including: before touching a patient; before aseptic procedures; after body fluid exposure risk; after touching a patient; and after touching patient surroundings. Hand hygiene compliance rate = (actual hand hygiene executions / required hand hygiene executions) × 100%.

Isolation Gown Usage Compliance Rate: Based on the indications for using isolation gowns, the ward designed an isolation gown usage compliance inspection form. The infection control nurse in the group randomly checked the isolation gown usage compliance of 50 healthcare workers in the emergency ICU before and after the implementation of the SMART goal management plan. The form includes compliance with isolation gown usage during aerosol-generating procedures, working in environments contaminated with burn wounds, handling secretions, pressure sores, drainage wounds, excreta, and stoma tubes. Isolation gown usage compliance rate = (actual isolation gown usages / required isolation gown usages) × 100%.

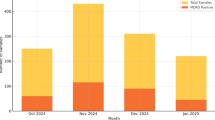

MDRO Infection Rate in the Ward: Data were sourced from the hospital’s real-time infection monitoring software. The occurrence of MDRO infection was identified if any sample (blood, urine, sputum, cerebrospinal fluid, etc.) sent for testing in the ward contained multidrug-resistant organisms. MDRO infection rate = (number of MDRO infections residing on the unit / number of patients residing on the unit in the same period in the ward) × 100%.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software. Paired t-tests were used to compare pre- and post-intervention knowledge scores. Chi-square tests were used to compare pre- and post-intervention compliance rates and infection rates.

Results

Participant characteristics

The study included 50 healthcare workers, with 16% being doctors and 84% being nurses. The majority of participants were female (68%), aged between 30 and 40 years (66%), and had a bachelor’s degree or lower (78%). The detailed demographic characteristics are presented in Table Changes in MDRO Prevention Indicators.

Following the implementation of the SMART-based infection control plan, significant improvements were observed in MDRO prevention indicators. Knowledge scores increased from (82.56 ± 4.14) to (90.80 ± 4.31) (p < 0.05). Hand hygiene compliance improved from 72.1 to 94.2%, and isolation gown use compliance increased from 60.2 to 87.6%, both with statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

MDRO infection rates

The implementation of the SMART-based infection control plan resulted in a significant reduction in MDRO infection rates. The infection rate decreased from 8.0% (16/200) pre-intervention to 5.1% (10/195) post-intervention (p = 0.027), indicating the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing MDRO infections in the emergency ICU (Table 3).

Discussion

MDRO infections significantly increase the length of hospital stays and financial burdens for critically ill patients17. These infections also severely impact patient outcomes and pose considerable challenges to clinical infection control efforts. MDRO carriers, contaminated healthcare workers’ hands, medical equipment, and hospital environments serve as primary sources of infection, typically spreading through contact and causing nosocomial infections2,18,19. Therefore, strengthening measures such as hand hygiene, environmental monitoring, isolation, and personal protection, along with comprehensive, targeted training and monitoring, is crucial for preventing MDRO infections and reducing their incidence.

This study, based on the SMART principles, integrated relevant guidelines, expert consensus, and action plans for MDRO infection control both domestically and internationally, to develop and implement an infection control plan. The results demonstrated that the SMART-based infection control measures significantly are related to the improvement of healthcare workers’ awareness of MDRO prevention and the reduction of MDRO infections in the adult ICU.

The study revealed that post-implementation of the SMART-based infection control plan, healthcare workers’ knowledge scores on MDRO prevention increased from (82.87 ± 3.92) to (91.43 ± 4.30). Hand hygiene compliance improved from 72.1% (124/172) to 94.2% (162/172), and isolation gown use compliance increased from 60.2 to 87.6%. These differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05), indicating that the SMART-based infection control measures effectively are related to enhancement of both knowledge and compliance among healthcare workers. The SMART principles, as a project management tool, have been widely applied in health care, educational training, and quality safety management7,20,21,22. Previous studies have shown that poor compliance with MDRO infection control measures is often related to a lack of knowledge, weak awareness, and inadequate preventive habits among staff23. To address this, our study applied the SMART principles in ICU infection control, yielding positive results consistent with previous findings by Zhang Jie et al.21.

Implementing the SMART principles effectively addresses deficiencies and gaps in hospital infection control. By setting specific, measurable goals, and developing relevant, actionable, and evaluable intervention plans, these principles help resolve identified issues. Strengthening hand hygiene management through adequate facilities and varied promotional methods, enhancing isolation measures with single-room isolation and gown use, and reinforcing environmental and equipment disinfection are all critical steps. Comprehensive training on these measures ensures healthcare workers not only increase their awareness but also master techniques in hand hygiene, aseptic operations, environmental cleaning, personal protective equipment use, and patient isolation23.

The study found that after implementing the SMART-based infection control plan, the MDRO infection rate decreased significantly from 8.0 to 5.1% (P < 0.05). This demonstrates the SMART-based infection control measures are related to the reduction of MDRO infection rates. The prevention and control of MDRO involve multiple links and risk factors, such as knowledge and attitude of medical staff in prevention and control, as well as implementation of measures16. Existing research indicates that standardized education for healthcare workers may significantly improve knowledge about infection prevention and control measures, thereby reducing the incidence of MDRO24. In this study, some measures were developed based on the SMART principle. These measures target weaknesses in awareness, skills, training, and monitoring, and form standardized control strategies based on guidelines and evaluation standards, enhancing relevance and effectiveness in managing MDRO infection risks.

In conclusion, integrating SMART principles with national and international MDRO infection control guidelines and standards, setting clear, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound management plans, and implementing targeted improvement measures and training can significantly enhance healthcare workers’ awareness and compliance, thereby reducing MDRO infection rates. However, this study is limited by its single-center, small-sample design and lacking of monitoring disinfection measures. The interpretation of the differences between the two phases in relation to the subgroups should be viewed with caution due to the low number of observations Future multi-center, large-sample studies are needed to further validate these findings and increase monitoring of environmental and equipment cleaning and disinfection effectiveness.

Data availability

Data and analytical methods in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Riley, M. M. The rising problem of Multidrug-Resistant organisms in intensive care units. Crit. Care Nurse. 39(4), 48–55 (2019).

Zhou, Y. et al. Clinical significance of MDRO screening and infection risk factor analysis in the ICU. Am. J. Transl Res. 13(4), 3717–3723 (2021).

West, K. H. & Cohen, M. L. Standard precautions–a new approach to reducing infection transmission in the hospital setting. J. Intraven Nurs. 20(6 Suppl), S7–10 (1997).

Xiong Yanhong, Z., Bin, X. & Xuenian Application of SMART principle in the patent management of healthprofessional. China Health Standard Manage. 10(9), 60–63 (2019).

Strogetskaya, E. & Betiger, I. The Smart Education Paradigm: Expected Outcomes and Real-Life Student Experience Diskurs. 7(2). 94–107 (2021).

Shaw, R. L. et al. Be SMART: examining the experience of implementing the NHS health check in UK primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 16, 1 (2015).

Jakubietz, R. G. et al. [Goal-setting in plastic surgery using the SMART principle]. Handchir Mikrochir P. 55(6), 450–456 (2023).

Fernando, S. A., Gray, T. J. & Gottlieb, T. Healthcare-acquired infections: prevention strategies. Intern. Med. J. 47(12), 1341–1351 (2017).

de Souza, L. M. et al. [Adherence to the five moments for hand hygiene among intensive care professionals]. Rev. Gaucha Enferm. 36(4), 21–28 (2015).

Marziali, E. et al. From infections to preventive actions monitoring in health facilities: an experience on MDROs. Eur. J. Public. Health ; 31(Supple3). (2021).

Van Hoof, V. et al. Failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) at the preanalytical phase for POCT blood gas analysis: proposal for a shared proactive risk analysis model. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 60(8), 1186–1201 (2022).

Ji, B. & Ye, W. Prevention and control of hospital-acquired infections with multidrug-resistant organism: A review. Medicine 103(4), e37018 (2024).

Gammon, J. & Hunt, J. COVID-19 and hand hygiene: the vital importance of hand drying. Br. J. Nurs. 29(17), 1003–1006 (2020).

Bénet, T. et al. Determinants of implementation of isolation precautions against infections by Multidrug-Resistant microorganisms: A Hospital-Based, multicenter, observational study. Infect. Cont. Hosp. EP. 38(10), 1188–1195 (2017).

Branch, R. & Amiri, A. Environmental surface hygiene in the OR: strategies for reducing the transmission of health Care-Associated infections. Aorn J. 112(4), 327–342 (2020).

Zhou, J., Chen, S. & Knowledge Attitudes, and practices of NICU Doctors and nurses toward prevention and control of nosocomial infection with multidrug resistant organism. Front. Pediatr. 10, 817030 (2022).

Neubeiser, A. et al. Mortality attributable to hospital acquired infections with multidrug-resistant bacteria in a large group of German hospitals. J. Infect. Public. Heal. 13(2), 204–210 (2019).

Li, Z. J. et al. The distribution and source of MRDOs infection: A retrospective study in 8 ICUs, 2013–2019. Infect. Drug Resist. 14, 4983–4991 (2021).

Alsehemi, A. F. et al. Assessment of risk factors associated with multidrug-resistant organism infections among patients admitted in a tertiary hospital - a retrospective study. Saudi Pharm. J. 31(6), 1084–1093 (2023).

Kalykbayeva, A. & Satova, А. Organization of self-assessment of students with Sen in inclusive education based on the smart principle (for example, mathematics lessons in primary school) bullet. Ser. Ped Sc. 65(1), 408–414 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of hospital infection prevention and control based on the SMART principle. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 48(7), 1059–1065 (2023).

Tangeraas Hansen, M. J. et al. Attitudes and self-efficacy towards infection prevention and control and antibiotic stewardship among nurses: A mixed-methods study. J. Clin. Nurs. 32(17–18), 6268–6286 (2023).

Phung, T. et al. SG-APSIC1069: implementing infection prevention bundle significantly reduced multidrug-resistant organisms infection and healthcare-associated infections in intensive care unit at a National hospital in Vietnam. Antimicrob. Steward Healthc. Epidemiol. 3(S1), s24–s25 (2023).

Abdelwahab, M. et al. Impact of infection prevention and control education program on improving knowledge, attitude and practices of the healthcare staff in Hemodialysis unit at Egyptian tertiary care facility AJMAH. ; 1–11. (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the hospitals for their assistance in recruiting the participants of this study. We would also like to thank the medical staff who participated in this study for their efforts.

Funding

This study was funded by the Henan Province Key Research and Development and Promotion Project (Science and Technology) [grant number 232102310235].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Liu Y was responsible for data acquisition and the drafting of the original manuscript. Cheng Y,Sun X and Yang S involved in data acquisition and interpretation. Ren Y and Wang D participated in data interpretation and revised the manuscript. Chen C made substantive intellectual contributions to the conception of the work, the interpretation of the data, and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Cheng, Y., Sun, X. et al. Implementation of a SMART-based infection control plan in an emergency intensive care unit: a prospective study. Sci Rep 15, 20001 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01416-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01416-1