Abstract

The presence of pharmaceutical compounds in aquatic environments has become a notable ecological issue, with compounds such as bromazepam, naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol being of particular concern due to their prevalence and potential biological effects on non-target species. This study aims to evaluate the effects of these pharmaceuticals on common carp (Cyprinus carpio), focusing on cytogenicity, genotoxicity, hematological, biochemical, neurological, and immunological responses. Juvenile carp were exposed to 15.54 µg/L bromazepam, 14.40 µg/L naproxen, 5.76 µg/L metoprolol, and 3.33 µg/L sotalol, respectively. Hematological analysis revealed significant reductions in red blood cell counts and hemoglobin levels, indicating potential anemia, especially in fish exposed to naproxen. Biochemical assays showed increased levels of albumin, globulin, and enzymes indicative of liver stress in exposed groups. Antioxidant defense enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase showed significant activity increases, suggesting oxidative stress. Apoptosis assays demonstrated elevated erythrocyte apoptosis, particularly in the naproxen group, which also exhibited the highest DNA damage. These findings highlight the ecological significance of pharmaceutical contamination and highlight the urgent need for thorough environmental risk assessments that take into account the health of both organisms and ecosystems, as well as the creation of mitigation plans for their detrimental effects on aquatic ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the presence of pharmaceutical compounds in aquatic environments has emerged as a significant ecological concern1. These compounds originated from various sources such as wastewater effluents, agricultural runoff, and improper disposal. They have been detected in surface waters globally at concentrations that, while often low, pose potential risks to aquatic organisms2. Pharmaceuticals are designed to have biological effects at low doses, raising concerns about their unintended impacts on non-target species when they enter the environment3. Among the multitude of pharmaceuticals found in aquatic environments, bromazepam, naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol are particularly noteworthy due to their widespread use and documented presence in water bodies4,5,6,7. Bromazepam, a benzodiazepine, is commonly prescribed for its anxiolytic properties8. Naproxen is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to treat pain and inflammation9. Metoprolol and sotalol are beta-blockers widely used in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases10,11. The extensive use of these pharmaceuticals leads to their persistent presence in the environment, where they can exert various biological effects on aquatic organisms12.

For aquatic animals, exposure to pharmaceutically active compounds (PhACs) in the environment may have significant sub-lethal ecological effects13. In particular, psychoactive medications are meant to modify behavior in humans as part of the prescribed treatment (antidepressants, anxiolytics, antipsychotics), or as a side effect of some medications (analgesics). They may also have a similar effect on aquatic life. This is due to the fact that many pharmacological targets and receptors are extensively conserved throughout the vertebrate taxonomic tree; so, fish may exhibit effects that are comparable to those observed in humans14. Pharmaceuticals including naproxen have reportedly been found in the plasma of fish kept in aquariums exposed to treated wastewater15.

Bromazepam in the aquatic environment leads to some behavioral changes in the aquatic organisms16. It can cause sedation and reduce the overall activity levels of fish17. This can affect their ability to forage, evade predators, and interact with their environment18. Fish exposed to bromazepam may exhibit changes in social behavior, including reduced aggression and altered schooling behavior. This can disrupt social hierarchies and breeding patterns18. Bromazepam is reported to have physiological impact on aquatic fish. Bromazepam exposure can interfere with the normal stress response in fish, making them less able to cope with environmental stressors19.

Juvenile meagre fish (Argyrosomus regius) exposed to venlafaxine, an antidepressant with pharmacological effects similar to those of bromazepam, may experience decreased reproductive success, either through direct effects on reproductive organs or through behavioral changes that affect mating20. Danio rerio can be beneficial when evaluating the toxicological effects of drugs that may have antidepressant properties21. As pollutants, antidepressant medications cause an immense amount of pollution in the environment. As a result of their mode of action, which involves modulating neurotransmitter activity, it is hypothesized that they may affect various biological processes in living things exposed to their residues in the water system by interfering with their development, behavior, and reproduction22. When sertraline was tested at low concentrations in the environment, it was found to accelerate the hatching process of Danio rerio larvae and induce altered behavior, such as avoiding the dark zones of a tank23. Similarly, zebrafish larvae exhibited hypolocomotion and delayed hatching when exposed to fluoxetine at levels found in municipal water samples. Additionally, the tested subjects’ acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity was shown to be inhibited in a dose-dependent manner24. However21, showed that venlafaxine concentrations in the environment had two different effects on Danio rerio larvae activity: at higher tested concentrations, it decreased zebrafish mobility, while at lower tested concentrations, it induced hyperlocomotion. Embryos and larvae exposed to antidepressant might experience developmental abnormalities, potentially leading to higher mortality rates in early life stages21. Subchronic exposure to naproxen was reported to have significant effects on the early life stages of common carp. These effects included disturbances in hatching, developmental rate, morphology, and histology, as well as increased mortality when combined with tramadol hydrochloride25. Previous studies subjected rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) to low doses of naproxen in aquaria26. They observed that the metabolites and total bioconcentration factors of naproxen in the bile of fish exposed to water varied from 500 to 2,300. It was reported that zebrafish exposed to metoprolol exhibited a reduced heart rate27. The hatching rate of fish embryos decreases with increasing exposure to metoprolol27. Additionally, there was a tendency for the metoprolol exposure to slightly raise fish mortality28. Previous study has been done on sotalol and its effect on the New Zealand mudsnail Potamopyrgus antipodarum29. The authors postulated that there would be fewer embryos in the brood pouches, slower adult snail growth, smaller newborns, and no influence on adult death rates based on the pharmacodynamic features of sotalol. The acute immobilization test with Daphnia magna indicated that the median lethal concentration was substantially higher than environmental concentrations30.

Common carp was selected for this study due to its ecological and scientific relevance. Common carp is a species with global distribution and significant importance in aquaculture, making it an ideal model organism for assessing environmental toxicity. Additionally, it is listed in the OECD guidelines as a recommended species for chemical testing31. Moreover, we specifically chose juvenile carp to avoid gender-related influences and because younger life stages are generally more sensitive to chemical exposures than adults. This allows us to better assess the potential sub-lethal effects of pharmaceutical exposure in an environmentally and scientifically relevant species. The selection of bromazepam, naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol for this study was driven by their widespread use, environmental persistence, and distinct pharmacological profiles that target different biological systems, making them representative of diverse pharmaceutical classes commonly detected in aquatic environments. Bromazepam, a psychoactive benzodiazepine, was included due to its potential to induce behavioral and stress-related changes in aquatic organisms, as evidenced by its effects on social interactions and coping mechanisms32. Naproxen, a widely used NSAID, was chosen because NSAIDs are among the most frequently detected pharmaceutical contaminants globally and have documented impacts on aquatic species, including developmental and reproductive effects33. Metoprolol, a beta-blocker, was selected for its known effects on cardiac function, hatching, and survival rates in fish embryos, while sotalol, another beta-blocker, was included due to its documented influence on growth and reproduction in aquatic invertebrates34. Together, these pharmaceuticals represent a range of commonly used drugs with varying mechanisms of action, providing valuable insights into their ecological impacts and serving as a basis for assessing the broader environmental risks of pharmaceutical mixtures. Current environmental risk assessment methodologies emphasize the importance of understanding the persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and toxicity profiles of individual contaminants to evaluate their ecological impact. However, aquatic organisms are rarely exposed to single compounds in isolation; instead, they encounter complex mixtures of various pharmaceuticals and other pollutants, which can interact in additive, synergistic, or antagonistic ways. The concentrations of bromazepam, naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol used in this study were selected based on their reported maximum concentrations in effluent from wastewater treatment plants, as indicated in recent literature35. These concentrations represent levels of pharmaceutical contaminants that are typically found in treated wastewater and serve as a realistic representation of environmental exposure. By using these concentrations, our study aims to evaluate the potential ecological effects of these pharmaceuticals under conditions that closely mirror actual environmental contamination, ensuring that our findings are both relevant and applicable to real-world scenarios. Studies focused on individual pharmaceuticals are crucial initial steps for determining baseline toxicity and understanding specific modes of action, as these insights help to predict potential risks in multi-contaminant scenarios. This study aims to evaluate the effects of bromazepam, naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol on common carp (Cyprinus carpio), focusing on cytogenicity and genotoxicity, hematological and biochemical parameters, and neurological and immunological responses.

Materials and methods

The current study followed the guidelines of the Animal Use and Care Committee of Assiut University, Egypt (Experimental protocol Number 07\2024\0056).

Chemicals

Bromazepam (CAS Number:1812-30-2), Naproxen CAS No.:22204-53-1), metoprolol (CAS No.:56392-17-7), and sotalol (CAS No.:959-24-0) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Deisenhofen, Germany).

Experimental set up and sampling procedures

The juvenile common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) was purchased from Aquaponic unit at Assiut University, Egypt. The acclimation of the test organisms was carried out over a period of two weeks to ensure they adjusted to the experimental conditions. Following acclimation, the experiment was conducted in rectangular tanks, each with dimensions of 100 cm × 70 cm × 50 cm. These tanks were used to house the organisms and allowed for continuous monitoring of key physicochemical parameters of the water throughout the study. The water in the tanks was maintained at an average temperature of 28.5 ± 0.21°C, with a pH value of 7.4 ± 0.35, providing a stable and neutral environment. Dissolved oxygen (DO) levels were kept at 6.9 ± 0.56 mg/L to ensure adequate oxygenation for the organisms, and the conductivity of the water was measured at 260.8 ± 5.26 mS/cm, reflecting the ionic composition and salinity. To maintain water quality and reduce waste products generated by the fish, 40% of the water volume in each tank was replaced daily. The replaced water was carefully re-dosed with appropriate treatments to match the original conditions, ensuring minimal disruption to the experimental parameters. The tanks were also subjected to a controlled photoperiod, set to a 12-h light: 12-h dark cycle (12:12). This simulated natural environmental conditions and ensured a consistent day-night rhythm for the duration of the experiment. Common carp fish with an average weight of 40.5 ± 6.74 g were divided into five groups with 30 fish per group. The experiment was done in triplicate tanks per group for two weeks. Four groups were exposed to bromazepam, naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol at nominal concentrations of 15.54 µg/L, 14.40 µg/L, 5.76 µg/L, and 3.33 µg/L, respectively35, while one group served as the control. The drugs were dissolved in distilled water to prepare the desired nominal concentrations and were added directly to the experimental tanks during daily water replacement. As distilled water was the solvent used, no separate vehicle control group was included, and the control group consisted of fish exposed to the same environmental conditions without any added drugs. At the end time, six fish from each group were chosen at random for sampling. Fish were placed on ice to minimize stress36,37.

Hematological and biochemical analysis

Blood samples were collected from the caudal veins of six fish per group and immediately placed in heparinized tubes. The Hb concentration and the number of blood cells were estimated within 30 min of blood collection. An automated technical analyzer (Mindray Bc-2800) was used to measure the red blood cells (RBCs, Million/ µl), white blood cells (WBCs, Thousands/µl), hematocrit (Ht, %), and hemoglobin (Hb, g/dl). The formulae described by38 were used to compute the mean corpuscular volume (MCV, µm3), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH, pg), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC, %). After being diluted 1:20 with a diluting fluid (saline solution), blood was put into a hemocytometer. The hemocytometer’s four large (1 mm2) corner squares were counted under an Olympus microscope at 640×. The total number of WBCs was computed in mm3 × 103, and the differential count (lymphocytes %, monocytes %, and neutrophils %) was demonstrated by staining blood films with Giemsa dye39.

Serum biochemical parameters, including albumin, globulin, albumin/globulin (A/G) ratio, total protein, glucose, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), creatine kinase (CK), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), were measured using commercially available diagnostic assay kits specifically designed for serum/plasma samples. All kits were obtained from Spectrum Diagnostics (Egyptian Company for Biotechnology, Cairo, Egypt) except albumin kit from Genesis company, Egypt, and were used strictly according to the manufacturer’s instructions without modification, unless otherwise specified. Each analyte’s kit catalog number is reported below and confirmed to be traceable to actual commercial assays, per reviewer request. All measurements were conducted in duplicate. Serum samples were collected without anticoagulants and centrifuged at 3000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were stored at − 20 °C and thawed only once prior to analysis. No matrix-specific dilution or pretreatment was performed beyond kit instructions, unless noted.

Albumin (g/dL) was determined using a colorimetric bromocresol green (BCG) method (Cat. No. 111003). In brief, 10 µL of serum was mixed with 1.0 mL of BCG reagent (pH 4.3 citrate buffer) and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. The resulting green complex was measured at 578 nm using a Jasco-V530 spectrophotometer (Jasco, Ottawa, Canada). Albumin concentrations were calculated based on a provided standard curve40. Globulin (g/dL) was calculated by subtracting albumin from total protein values (Cat. No. 819002), obtained as described below. The A/G ratio was then derived by dividing albumin by globulin41. Total protein (g/dL) was measured using the Biuret method (Cat. No. 310001). A total of 20 µL of serum was mixed with 1.0 mL of Biuret reagent and incubated at room temperature (15–25 °C) for 10 min. Absorbance was read at 546 nm, and concentrations were calculated against a provided protein standard42.

Glucose (mg/dL) was measured using the glucose oxidase–peroxidase (GOD-PAP) method (Cat. No. 250001). A 10 µL aliquot of serum was added to 1.0 mL of reagent and incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. Absorbance was recorded at 546 nm, and concentrations were calculated against the kit’s 100 mg/dL glucose standard43.

AST (U/L) activity was assessed using the 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine method (Cat. No. 260001). Briefly, 100 µL of serum was mixed with 0.5 mL of buffer reagent (R1) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Then, 0.5 mL of color reagent (R2) was added and incubated at room temperature for 20 min, followed by addition of 5.0 mL of 0.4 mol/L NaOH. Absorbance was measured at 546 nm44. ALT (U/L) activity was determined using the same hydrazone-based principle (Cat. No. 264001). The assay followed the same steps as AST, using ALT-specific buffer and reagents45. ALP (U/L) was quantified using a kinetic colorimetric assay based on the IFCC method (Cat. No. 217003). Serum (10 µL) was added to 1.0 mL of reagent containing p-nitrophenyl phosphate in alkaline buffer. The reaction was monitored at 405 nm every 60 s for 3 min after a 180-s delay at 37 °C. Enzyme activity was calculated using the kit’s kinetic formula46.

Creatine kinase (CK; U/L) was measured using a kinetic enzymatic method aligned with DGKC and IFCC recommendations (Cat. No. 238004). A working reagent was prepared by mixing four parts of Reagent 1 with one part of Reagent 2. A 20 µL serum sample was added to 0.5 mL of this working reagent, and absorbance was monitored at 340 nm at 1-min intervals for 3 min at 37 °C. CK activity was calculated from the NADPH formation rate47.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; U/L) was assessed via a UV kinetic assay (Cat. No. 283005). The working reagent (phosphate buffer with pyruvate and NADH) was freshly prepared by mixing 4 parts Reagent 1 and 1 part Reagent 2. In each assay, 500 µL of the working reagent was added to 10 µL of serum in a pre-warmed cuvette (37 °C). Absorbance was recorded at 340 nm at 1-min intervals for 3 min. LDH activity was calculated based on the rate of NADH oxidation48.

All biochemical assays were validated for linearity, reproducibility, and were performed in accordance with the kit’s stated intended matrix (serum). The same batch of reagents was used across experimental groups to minimize inter-assay variability.

Antioxidant parameters measurements

Superoxide Dismutase (SOD, Unit/mL), Catalase (CAT, Unit/mL), and Glutathione Peroxidase (GPX) activities were measured using kits of SGMitalia Company USA. Each sample was tested in triplicate using a Biochrom Ltd microplate reader to measure the SOD levels in serum at 450 nm49,50. The CAT activity in serum was measured in triplicate using a UV–VIS spectrophotometer set to 240 nm49. GPX activity was determined following the method described by51.

Apoptosis and comet assay

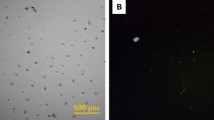

According to52, methanol-fixed smears stained with Acridine Orange dye (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA) were used to identify apoptotic erythrocytes. Cells were examined using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 fluorescent microscope (× 200) equipped with a Sony AVT-Horn digital 3 CCD color video camera. According to53, blood (50 μL) was drawn from the caudal veins after two weeks of exposure. It was then promptly frozen to prevent endogenous DNA damage and to prevent DNA repair in the unfixed cells54. A hemocytometer was also used to evaluate cell viability. A previously published procedure by55 was used for a neutral comet test, with a few minor adjustments53. A Zeiss Axioplan 2 fluorescent microscope (× 200) equipped with a digital 3 CCD color video camera (Sony, AVT-Horn) was used to observe the cells. The tail moment score was computed by analyzing each cell’s comet picture using CASP software56.

Statistical analysis

All data were reported as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) using statistical analysis performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.). One-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey’s HSD tests were conducted to identify significant differences between all tested groups and from controls as well as between each other. The statistical significance of differences between treatments and controls was set at P ≤ 0.05. Asterisk superscript (*) visually indicated the significant level (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

Results

Hematological parameters

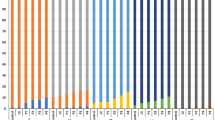

Hematological testing in fish is essential for assessing health status and detecting metabolic diseases by measuring blood parameters and comparing them to established norms, as shown in Table 1. In this study, fish exposed to bromazepam, naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol exhibited significant reductions in red blood cell (RBC) counts compared to the control group (1.392 ± 0.038 million/µL). The RBC counts for the treated groups were recorded as follows: bromazepam (1.3 ± 0.018 million/µL), naproxen (1.225 ± 0.030 million/µL), metoprolol (1.265 ± 0.018 million/µL), and sotalol (1.313 ± 0.039 million/µL). Significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) were observed between the bromazepam and naproxen groups, as well as between the naproxen and sotalol groups (Fig. 1a). Hemoglobin levels were significantly reduced (p ≤ 0.05) in the bromazepam, naproxen, and metoprolol groups compared to controls, while the sotalol group exhibited a non-significant decrease. However, hemoglobin levels in the sotalol group were significantly higher (p ≤ 0.05) than in the naproxen group. Additionally, hemoglobin levels in the bromazepam and metoprolol groups were significantly higher (p ≤ 0.05) than in the naproxen group (Fig. 1b). Hematocrit (Ht) levels in the naproxen group were significantly lower (p ≤ 0.05) than in all other tested groups, including the control group (Fig. 1c). Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) showed a significant increase in the bromazepam, metoprolol, and sotalol groups relative to controls (Fig. 1d). Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) was significantly increased (p ≤ 0.05) only in the sotalol group, with no significant changes observed in the other groups (Fig. 1e). MCHC was non-significantly changes in tested groups compared to the control group (Fig. 1f). White blood cell (WBC) counts were significantly reduced (p ≤ 0.05) in the bromazepam and naproxen groups compared to controls, with significant variations recorded among the tested groups (Fig. 1). Neutrophil counts did not differ significantly between the tested groups and the control, but significant differences were observed among the tested groups themselves. Lymphocyte counts were significantly higher in the sotalol group compared to the control group, while monocyte counts were decreased across all tested groups compared to controls.

Biochemical parameters

The hepatopancreatic function parameters affected by exposure to bromazepam, naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol were presented in Table 2. Albumin increased in all tested groups more than the control group. It increased significantly (p ≤ 0.05) in fish groups exposed to naproxen and sotalol compared to the control group (Fig. 2a). Globulin changed in all tested groups compared to the control group. In addition, it was significantly increased (p ≤ 0.05) in the naproxen group compared to the control group. A/G ratio was not significantly changed in all groups relative to the control one (Fig. 2b, c). Total protein, glucose, AlP, and lactate dehydrogenase were significantly increased (p ≤ 0.05) in all groups compared to the control fish (Fig. 2d, e, g, h, j). AST and creatine kinase were significantly increased (p ≤ 0.05) in fish groups exposed to bromazepam, naproxen, and sotalol compared to the control group (Fig. 2f, i).

Antioxidant defense enzymes

Table 3 illustrates how the antioxidant defense enzymes of common carp are affected by bromazepam, naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol. In comparison to the control group, there was a significant increase in superoxide dismutase SOD (P ≤ 0.05) following exposure to bromazepam, naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, compared to the control group, there was a substantial increase in catalase (P ≤ 0.05) following exposure to bromazepam, naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, after being exposed to sotalol, naproxen, metoprolol, and bromazepam, GPx increased significantly (P < 0.0001) in comparison to the control group (Fig. 3C).

Apoptosis level and DNA damage

In comparison to the control group, the percentage of apoptotic erythrocytes in common carp exposed to bromazepam increased significantly at (p ≤ 0.05). Exposure to naproxen leads to a significant increase in the percentage of apoptosis compared to the control group and other treated groups (p ≤ 0.05). Fish groups exposed to metoprolol and sotalol showed markedly increased apoptosis relative to the control group as presented in Fig. 4a.

(a) The percentage of apoptotic cells (%) in common carp exposed to bromazepam, naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol. (b) The tail moment score (%) in common carp exposed to bromazepam, naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol. The data was presented as mean ± SE, (n = 6). The significant difference between each two groups was denoted according to P < 0.05, *; P < 0.01, **; P < 0.001, ***; and P < 0.0001, ****.

The amount of DNA damage was evaluated by measuring the percentage tail moment. Figure 4b displays the comet assay tail moment values. After exposure to naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol, fish groups showed a distinct and statistically significant increase in tail moment values compared to the control group (p ≤ 0.05). The naproxen exposure showed the highest amount of DNA damage.

Discussion

Hemato-biochemical parameters

Hematological testing is a vital tool for assessing the health and metabolic status of fish by providing detailed information on blood parameters, which can indicate underlying physiological and pathological conditions57,58,59. Numerous publications claim that hazardous substances can cause erythrocyte morphological abnormalities such amitosis, hemolysis, distortion of the cells, or nuclear abnormalities60,61. In this study, we observed significant alterations in several hematological parameters in fish exposed to bromazepam, naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol compared to the control group, indicating the potential impact of these substances on fish health. The significant reduction in red blood cell (RBCs) counts in the treated groups highlights a potential hematotoxic effect of these substances. While these effects are observed in carp at environmentally relevant concentrations, it is important to note that therapeutic doses in humans are significantly higher (e.g., sotalol is prescribed at 80–320 mg/day in humans62, compared to 3.33 µg/L in this study). Regulatory documents from the FDA and EMA do not report similar hematotoxic effects (e.g., anemia, RBC suppression) in humans at therapeutic doses, suggesting species-specific differences in susceptibility. Carp may be more vulnerable due to differences in metabolism, detoxification capacity, and continuous exposure routes63. The specific decrease in RBCs could be indicative of anemia or impaired erythropoiesis64, which might be caused by the direct or indirect toxic effects of these compounds on the hematopoietic system. It was reported that many fish species are susceptible to poikilocytosis, which can be triggered by a variety of factors including pollution exposure, nutritional deficits, pathogenic agents, and environmental stressors65,66. Some pharmaceuticals may cause oxidative stress, which can result in hemolysis, or the deterioration of red blood cells. An imbalance between the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant defense mechanisms leads to oxidative stress. This may harm red blood cell membranes, rupturing them and lowering the number of red blood cells67. Certain substances might be harmful to the bone marrow, the hematopoietic tissue that produces red blood cells, which would slow down the process of making red blood cells, or erythropoiesis68.

Furthermore, hemoglobin levels were significantly reduced in the bromazepam, naproxen, and metoprolol groups. This reduction in hemoglobin could be a result of decreased RBCs counts, suggesting that the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood is compromised in these fish69. Interestingly, hemoglobin levels were significantly higher in the sotalol group compared to the naproxen group, which may indicate different mechanisms of action or varying degrees of hematological impact among the tested compounds. Previous work on naproxen reported that the hematological results exhibited a significant decrease in WBC, RBC, hemoglobin, and hematocrit in the group treated with naproxen compared to the control group70. They reported that naproxen treatment led to a significant decrease in red blood cell (RBC) count. This decrease is thought to occur due to the production of free radicals, which interact with the cell membranes of RBCs, resulting in hemolysis and the destruction of red blood cells71. Additionally, naproxen has been shown to reduce hemoglobin levels, a finding that aligns with previous work suggesting that the destruction of RBCs is a contributing factor to this effect72. Furthermore, naproxen’s impact on hematocrit levels could be linked to its influence on platelet aggregation. Naproxen has been shown to impair platelet aggregation, which could explain the decreased hematocrit observed in our study, as supported by findings in human studies73.

The hematocrit (Ht), which represents the percentage of red blood cells (RBCs) in relation to total blood volume, is an important hematological parameter that can provide insights into the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood and overall blood health74. Changes in hematocrit levels can be indicative of various pathological conditions, including anemia, blood dilution, and dehydration, as well as alterations in RBC production or destruction. In our study, hematocrit (Ht) levels were significantly lower in the naproxen group compared to all other groups, including the control. This decrease further supports the evidence of anemia or blood dilution effects in the naproxen-treated fish. Mean corpuscular volume (MCV) was significantly increased in the bromazepam, metoprolol, and sotalol groups, which could suggest a compensatory response to maintain adequate oxygen transport by increasing the size of the remaining erythrocytes. Over the period of the 12-day exposure to anti-inflammatory drug, fish treated with acetylsalicylic acid exhibited a significant (P < 0.05) decrease in their levels of Hb, hemoglobin-ct, and RBCs in comparison to the control group. Conversely, there was a noteworthy (P < 0.05) rise in the MCV, MCH, MCHC, and WBC75. It was reported that exposure to chemical compounds (MeHg) may potentially impact the red blood cell turnover process, leading to an increase in the number of older cells in circulation and the induction of anemia76. The increase in MCH suggests that these compounds might affect hemoglobin synthesis or erythrocyte morphology, potentially leading to a higher hemoglobin content per cell without a proportional increase in overall RBC count. Red blood cell edema or the discharge of enlarged red blood cells into the circulation during stress were the causes of an elevated MCV and MCH77. The macrocytic nesmochromic form of anemia was suggested by the elevations in MCV and MCH as well as the decreased MCHC value78. Red blood cells (RBC) and mean cellular hemoglobin content (MCHC) significantly decreased following 96 h of exposure to anti-inflammatory drugs at 50 and 500 μg/L. White blood cells (WBC), hemoglobin (Hb), hematocrit (Hct), mean cellular volume (MCV), and mean cellular hemoglobin (MCH) levels all rose79. It was determined that rainbow trout subjected to carbamazepine (96 h LC50) exhibited considerably reduced MCV and lymphocytes than the control group80.

The low MCV and MCH in the current study may be due to the large proportion of immature red blood cells in the bloodstream. Additionally, a rise in erythrocyte volume under stressful conditions could be another explanation81. White blood cells (WBCs) are crucial for innate immune defense and are involved in the regulation of immunological function in the organism; for these reasons, blood cells, especially WBCs, are frequently used as indicators of fish health (Fazio, 2019). The significant reduction in white blood cell (WBC) counts in the bromazepam and naproxen groups indicates a potential immunosuppressive effect of these compounds. WBCs are crucial for the immune response, and their reduction can make fish more susceptible to infections and diseases82. The significant variations in WBC counts among the tested groups underline the differential impact of these substances on the immune system. Neutrophil counts did not show significant changes between the control and treated groups; though significant differences were observed among the treated groups themselves. This suggests that neutrophils might be less sensitive to these treatments or that their responses are more variable. On the other hand, When Claris gariepinus was exposed to varying concentrations of atrazine and metalochlor, the results showed that both male and female C. gariepinus had increased levels of WBC, neutrophils, monocytes, MCH, and MCHC83. This is consistent with previous research on the acute hemopathological analysis of fish exposed to toxicants, specifically Sarotherodon melanotheron84. An immunological reaction to the toxicants is demonstrated by the increase in WBC, neutrophils. Studies have demonstrated that the species, chemical, and length of exposure all affect the alterations in fish haematological indices that toxicants produce and the reactions they trigger. They are also affected by the type, quality, and quantity of chemicals present in the water. They can all result in both reversible and irreversible changes to fish haematological parameters85. Lymphocyte counts were significantly increased in the sotalol group compared to the control, which could indicate an adaptive immune response or a compensatory mechanism to counteract the chemical effects86,87. Conversely, monocyte counts were decreased across all treated groups compared to controls, suggesting a general suppressive effect on this particular leukocyte population. It was reported that sulfur dioxide (SO2) was substantially linked to a decreased WBC number, especially neutrophils and monocytes. Though there was inconsistent data from in vitro research, SO2, an irritating and colorless environmental pollutant produced by numerous industrial processes, demonstrated the potential for genotoxicity and lymphocyte aberration in in vivo investigations88,89.

Biochemical parameters

The hepatopancreatic function parameters presented in the study indicate significant biochemical changes in fish exposed to bromazepam, naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol. These findings suggest potential hepatic and pancreatic toxicity associated with these pharmaceuticals, commonly found in aquatic environments due to pharmaceutical contamination. The observed increase in albumin across all test groups, with significant increases in the naproxen and sotalol groups, indicates a systemic response to these drugs. Albumin, a key plasma protein, often increases in response to liver function changes or stress90. While these biochemical changes are significant in carp, it is important to contextualize these findings with human toxicology. For example, naproxen is known to cause gastrointestinal and renal toxicity in humans91, but its effects on liver enzymes (e.g., ALT, AST) are less commonly reported92. This discrepancy may be due to differences in metabolic pathways between humans and fish. While common carp possess cytochrome P450 enzymes (e.g., CYP1A), as evidenced by their role in detoxification and oxidative stress responses, their metabolic capacity or efficiency may differ from that of humans. For example, the activity of CYP1A in carp is significantly reduced under arsenic exposure, leading to increased oxidative stress and hepatotoxicity93. This suggests that, although carp have detoxification pathways, they may be less robust or more easily overwhelmed compared to humans, making them more susceptible to pharmaceutical-induced toxicity at lower concentrations94. These differences in metabolic resilience could explain the heightened sensitivity of carp to environmental contaminants. Pharmaceutical chemical exposure can cause stress or damage to the liver, which causes the liver to produce more albumin as a compensatory response to sustain physiological functioning and maintain osmotic equilibrium95. Exposure to pharmaceuticals can induce physiological stress in fish, which activates their innate immune response. This stress triggers the production of acute-phase proteins, including albumin, as part of a compensatory mechanism to address the systemic alterations caused by the stressor. Acute-phase proteins play a critical role in restoring homeostasis during such conditions, highlighting the fish’s response to pharmaceutical contaminants in their environment96,97.

Our findings indicate that pharmaceutical exposure in carp leads to an increase in albumin levels, measured at concentrations below 0.8 g/dL, during the acute-phase response. This observation aligns with the physiological alterations induced by stress, which is known to stimulate acute-phase proteins, including albumin. However, in fish like carp, the role and prevalence of albumin differ significantly compared to mammals or even other fish species, such as trout98.

Previous studies have suggested that albumin is absent in carp plasma, with high-density lipoproteins compensating as the primary transport molecules for free fatty acids99,100. This evolutionary adaptation highlights the unique transport mechanisms in carp. Nevertheless, our results challenge the hypothesis of complete albumin absence, suggesting the presence of albumin or albumin-like proteins at low concentrations, which may become detectable during acute-phase responses. This increase could indicate a compensatory role for albumin-like proteins in carp under stress conditions induced by pharmaceutical exposure. Interestingly, studies on trout and other species with higher albumin levels demonstrate intermediate reliance on lipoproteins for transport, while mammals predominantly rely on albumin. These differences between fish and human albumin could be attributed to variations in plasma protein composition and binding capacities98. This distinction underscores the necessity of expanding the experimental database on fish plasma proteins to refine predictive models for fish bioaccumulation and stress responses. Further studies characterizing the amino acid sequence and structure of carp albumin are warranted to elucidate its role in the observed acute-phase response.

The significant rise in globulin levels in the naproxen group suggests an immune or inflammatory response, as globulins are associated with immune function101. These elevations could imply an adaptive response or a compensatory mechanism due to drug-induced hepatic stress102.

The albumin/globulin (A/G) ratio remained non-significantly changed in all groups, suggesting a balanced increase in both albumin and globulin levels. This ratio is a useful indicator of overall protein health in the blood, and its stability despite exposure to these drugs may indicate that while individual protein levels are altered, the relative balance between albumin and globulin is maintained. The glucose level increased in all tested groups compared to the control group. According to previous studies103,104,105, blood glucose levels rise when fish are under stress. In C. gariepinus exposed to TiO2 NPs, serum glucose levels also rose as Ti concentrations and exposure times increased106. They supposed that the rise in glycogenolysis brought on by an increase in energy requirements as a result of metal stress may account for the rise in blood glucose.

The significant increases in total protein, alanine transaminase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (LP), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) across all groups (p ≤ 0.05) are indicative of hepatic cellular damage or increased hepatic activity107,108,109. ALT and ALP are specific markers of liver health, and their elevation typically signals hepatocellular injury or cholestasis. LDH, a marker for tissue damage, further corroborates the presence of cellular stress or damage likely induced by pharmaceuticals. The significant increases in aspartate transaminase (AST) and creatine kinase (CK) in fish exposed to bromazepam, naproxen, and sotalol (p ≤ 0.05) further support the evidence of hepatic and possibly muscular damage110,111. AST is another enzyme indicative of liver damage, and its elevated levels alongside ALT strengthen the case for hepatotoxicity. Creatine kinase, primarily a muscle enzyme, suggests additional stress or damage to muscular tissues, possibly due to systemic toxicity110,112. According to a previous investigation, fish samples from polluted sites were shown to have significantly higher levels of ALT, AST, ALP, and LDH than fish samples from control sites without pollution113. This is consistent with other study that added mercuric oxide to the feeding program and led to a considerable increase in ALT and AST in the serum of C. gariepinus fish114. The collective data from these biochemical markers paint a concerning picture of the impact of pharmaceutical contaminants on aquatic life. The consistent pattern of elevated liver enzymes and proteins across different drugs suggests that these substances, even at environmental concentrations, can provoke significant physiological stress in fish. This stress could lead to compromised health, reduced growth, and potentially increased mortality, posing a threat to aquatic ecosystems. These pharmaceuticals’ physiological stress may have an impact on behavior as well. It was observer a significant decrease in AST and ALT activities75.

Antioxidant defense enzyme activity

Catalase decomposes hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen, thus protecting cells from oxidative damage115. The significant rise in CAT activity implies an elevated level of hydrogen peroxide in the treated fish, reflecting the oxidative challenge posed by the exposure to these compounds116. SOD activity significantly increased in fish exposed to bromazepam, naproxen, metoprolol, and sotalol. SOD is a crucial enzyme that catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide radicals into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, providing the first line of defense against reactive oxygen species (ROS)117. The elevated SOD activity suggests an increased production of superoxide radicals, which may result from the metabolism of these pharmaceuticals, leading to enhanced oxidative stress118. In addition to serving as an indicator of oxidative damage to lipids, SOD may also be responsible for the up-regulation of antioxidant enzymes119. Similar results were reported for common carp exposed to chemical stressor that leads to enhancing the CAT and SOD levels116. Juvenile rainbow trout exposed to carbamazepine showed noticeably elevated levels of SOD, CAT, GPx, and GR activity in their livers80. It was recorded notable changes in a number of antioxidant markers, including glutathione, lipid peroxidase, catalase, and SOD75. GPx reduces hydrogen peroxide and lipid peroxides to water and corresponding alcohols using glutathione as a substrate120. The marked increase in GPx activity further corroborates the presence of elevated oxidative stress and the requirement for enhanced detoxification of peroxides generated in response to stressor121. The observed oxidative stress in carp may not directly translate to humans due to differences in antioxidant defense mechanismsFor example, humans have higher baseline levels of antioxidant enzymes like SOD (superoxide dismutase) and CAT (catalase), which play a critical role in neutralizing reactive oxygen species (ROS) and mitigating oxidative stress122,123. This robust antioxidant defense system allows humans to better tolerate pharmaceutical-induced oxidative stress at therapeutic doses. In contrast, fish like carp may have lower baseline levels of these enzymes or less efficient antioxidant systems, making them more susceptible to oxidative damage even at lower, environmentally relevant concentrations51,124. These differences in antioxidant capacity highlight the need for species-specific risk assessments when evaluating the ecological impact of pharmaceuticals. This further underscores the need for species-specific risk assessments when evaluating the ecological impact of pharmaceuticals.

Apoptosis and comet assay

These results collectively highlight the differential impacts of various pharmaceuticals on common carp, with a particular emphasis on their cytotoxic and genotoxic effects. Comet, DNA fragmentation, and micronucleus tests are three different assays that can be used to assess the genotoxicity of xenobiotics on fish nucleated erythrocytes125. Evaluation of oxidative stress, toxicity-induced apoptosis, and other metrics of cellular damage may potentially benefit from the use of erythrocytes126,127. The significant increase in apoptotic erythrocytes upon exposure to the four tested compounds suggests that these substances can induce programmed cell death, potentially compromising the fish’s ability to maintain normal physiological functions. The most severe apoptosis was observed with naproxen, aligning with its pronounced genotoxic effects as indicated by the comet assay results.

While apoptosis and genotoxicity are observed in carp, these effects are not commonly reported in humans at therapeutic doses of these pharmaceuticals. Regulatory documents from the FDA and EMA do not highlight apoptosis or monocyte suppression as significant concerns for human patients128. While In humans, pre-approval databases for pharmaceuticals are often insufficient to detect low rates of serious hepatotoxicity, necessitating robust post-marketing monitoring systems like the FDA’s MEDWATCH program129. Similarly, in aquatic environments, the long-term and cumulative effects of pharmaceutical contaminants on fish populations remain poorly understood due to limited monitoring and regulatory oversight. This suggests that carp may be more susceptible due to differences in cellular repair mechanisms, continuous exposure, and lower detoxification capacity. Future studies should explore these species-specific differences to better understand the ecological and human health implications of pharmaceutical contamination.

The increase in DNA damage, as measured by the tail moment, further corroborates the harmful effects of these pharmaceuticals on aquatic life130. The substantial genotoxicity observed with naproxen exposure is of particular concern, pointing towards its potential to cause long-term genetic damage, which could have repercussions on the health and reproductive viability of the fish population131. Study on Zebra fish reported that exposure to pharmaceuticals can cause both DNA and oxidative damages Neutral agarose gel electrophoresis was used to examine DNA damage photoinduced by four nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications132. Previous study demonstrates that carbamazepine exposure at environmentally relevant concentrations causes DNA damage and apoptosis in Chinese rare minnows (Gobiocypris rarus). The observed effects were mediated through the Ras/Raf/ERK/p53 signaling pathway. Specifically, carbamazepine exposure led to significant increases in DNA damage, apoptotic rates, and activation of key molecular pathways associated with mitochondrial apoptosis and cell cycle regulation, indicating a toxicological impact on liver tissue in both male and female minnows133.

The results of this study regarding genotoxicity and cytotoxicity may have serious consequences for the fish’s ability to reproduce. Reproductive success may be hampered by DNA damage and death in germ cells, which can result in transgenerational genetic alterations, decreased fertility, or an increase in the frequency of developmental defects in offspring134. Pharmaceuticals such as naproxen and bromazepam have been linked to endocrine disruption in other species, which may affect gametogenesis, hormone regulation, and spawning behavior135. Population losses may result from extended exposure to these pollutants in natural settings, particularly in species with low rates of reproduction or substantial parental investment.

The consequences of acute exposure were the focus of this investigation; on the other hand, it is important to consider the possible cumulative effects of long-term, low-dose exposure to pharmaceutical pollutants. Prolonged exposure to these substances may cause toxins to gradually accumulate in tissues, even at sub-lethal quantities, which could cause long-term physiological deficits136. Over time, such cumulative effects may lead to more pronounced implications on immunological function, development, and reproductive success in addition to exacerbating the observed hematological and biochemical changes. This raises concerns about the health of fish populations inhabiting pharmaceutical-contaminated waters, particularly as they are subject to continual exposure. The observed alterations in fish health resulting from exposure to pharmaceuticals may have wider ecological implications. Moreover, fish may be less resistant to environmental changes because of the stress brought on by pharmaceutical exposure, which might increase the effects of other stressors like habitat loss, climate change, or other contaminants.

Environmental regulations must manage the introduction of pharmaceutical pollutants into water bodies due to the possible cumulative and long-term effects on fish populations and aquatic ecosystems. To reduce the hazards to aquatic life, more stringent laws governing the disposal of pharmaceuticals and improved wastewater treatment technologies are essential137. Long-term, multigenerational studies should also be given priority in future research to completely understand the ecological effects of prolonged exposure to pharmacological combinations. The summary of previous studies can be shown in Table 4.

Conclusion

This study provides valuable insights into the physiological and genotoxic effects of pharmaceutical contaminants, contributing to a broader understanding of their ecological impact. By investigating diverse parameters, such as hematological and biochemical changes, the research enhances our knowledge of how these drugs affect aquatic organisms. These findings can be instrumental in improving ecological risk assessments by identifying sensitive biomarkers that signal early signs of contamination in aquatic ecosystems. To protect water quality and biodiversity, specific recommendations include the implementation of routine monitoring programs for water bodies, focusing on commonly detected pharmaceuticals and their cumulative effects. Developing and improving wastewater treatment technologies to target pharmaceutical contaminants is also essential, along with promoting policies that encourage the safe disposal of unused medications to prevent environmental release. While the implementation of strategies to reduce the entry of these pharmaceuticals into water bodies is challenging, it is feasible through a combination of technological innovations and public awareness campaigns. Advanced filtration techniques, such as reverse osmosis or activated carbon, have shown promise in removing pharmaceuticals from wastewater, but further research is needed to make these technologies more cost-effective and scalable. Collaboration between environmental agencies, industries, and policymakers will be critical in ensuring their successful adoption. Future research should focus on long-term studies to assess the chronic effects of pharmaceutical pollutants on aquatic ecosystems. These findings can further inform environmental risk assessments, guiding regulations and protective measures to safeguard aquatic life and preserve ecosystem health.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Mezzelani, M., Gorbi, S. & Regoli, F. Pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environments: Evidence of emerged threat and future challenges for marine organisms. Mar. Environ. Res. 140, 41–60 (2018).

Ritter, K. S., Paul Sibley, K. H., Patricia, K., Gevan, M., Beth Linton, L., Sources, pathways, and relative risks of contaminants in surface water and groundwater: A perspective prepared for the Walkerton inquiry. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A, 2002. 65(1): 1–142.

Arnold, K. E., et al. Medicating the environment: Assessing risks of pharmaceuticals to wildlife and ecosystems, 2014, The Royal Society. p. 20130569.

Ríos, A. L. M. et al. Pharmaceuticals as emerging pollutants: Case naproxen an overview. Chemosphere 291, 132822 (2022).

Voigt, M. et al. Metoprolol and its degradation and transformation products using AOPs—assessment of aquatic ecotoxicity using QSAR. Molecules 26(11), 3102 (2021).

Godoy, A. A. et al. Assessment of the ecotoxicity of the pharmaceuticals bisoprolol, sotalol, and ranitidine using standard and behavioral endpoints. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 5469–5481 (2020).

Cunha, D. L., Mendes, M. P. & Marques, M. Environmental risk assessment of psychoactive drugs in the aquatic environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 78–90 (2019).

Jones, B. D. M., Husain, M. I.: Tranquilizer/anxiolytics: Benzodiazepines (intermediate-acting)–alprazolam, bromazepam, clonazepam, lorazepam. NeuroPsychopharmacotherapy, 2021: p. 1–12.

Weisman, S. Naproxen for post-operative pain. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 24, 62–70 (2021).

Martínez-Milla, J. et al. Role of beta-blockers in cardiovascular disease in 2019. Rev. Española de Cardiología (English Edition) 72(10), 844–852 (2019).

Augustin, N., Alvarez, C., Kluger, J. The arrhythmogenicity of sotalol and its role in heart failure: A literature review. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2022: p. 10–1097.

Bilal, M. et al. Antibiotics traces in the aquatic environment: persistence and adverse environmental impact. Curr. Opinion Environ. Sci. Health 13, 68–74 (2020).

Dos Santos, C. R. et al. Aquatic concentration and risk assessment of pharmaceutically active compounds in the environment. Environ. Pollut. 290, 118049 (2021).

McArdle, M. E. et al. Critical review of read-across potential in testing for endocrine-related effects in vertebrate ecological receptors. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 39(4), 739–753 (2020).

Brown, J. N. et al. Variations in bioconcentration of human pharmaceuticals from sewage effluents into fish blood plasma. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 24(3), 267–274 (2007).

Cerveny, D. et al. Bioconcentration and behavioral effects of four benzodiazepines and their environmentally relevant mixture in wild fish. Sci. Total Environ. 702, 134780 (2020).

Chen, K. et al. Impacts of chronic exposure to sublethal diazepam on behavioral traits of female and male zebrafish (Danio rerio). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 208, 111747 (2021).

Brodin, T. et al. Ecological effects of pharmaceuticals in aquatic systems—impacts through behavioural alterations. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 369(1656), 20130580 (2014).

Brandão, F. P. et al. Short-term effects of neuroactive pharmaceutical drugs on a fish species: Biochemical and behavioural effects. Aquat. Toxicol. 144, 218–229 (2013).

Maulvault, A. L. et al. Differential behavioural responses to venlafaxine exposure route, warming and acidification in juvenile fish (Argyrosomus regius). Sci. Total Environ. 634, 1136–1147 (2018).

Lachowicz, J. et al. Zebrafish as an animal model for testing agents with antidepressant potential. Life 11(8), 792 (2021).

Fong, P. P. & Ford, A. T. The biological effects of antidepressants on the molluscs and crustaceans: A review. Aquat. Toxicol. 151, 4–13 (2014).

Yang, H. et al. Molecular and behavioral responses of zebrafish embryos/larvae after sertraline exposure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 208, 111700 (2021).

de Farias, N. O. et al. Exposure to low concentration of fluoxetine affects development, behaviour and acetylcholinesterase activity of zebrafish embryos. Comput. Biochem. Physiol. C: Toxicol. Pharmacol. 215, 1–8 (2019).

Sehonova, P. et al. Toxicity of naproxen sodium and its mixture with tramadol hydrochloride on fish early life stages. Chemosphere 188, 414–423 (2017).

Brozinski, J.-M. et al. Detection of naproxen and its metabolites in fish bile following intraperitoneal and aqueous exposure. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 18(5), 811–818 (2011).

Sun, L. et al. Toxicity and enantiospecific differences of two β-blockers, propranolol and metoprolol, in the embryos and larvae of zebrafish (Danio rerio). Environ. Toxicol. 29(12), 1367–1378 (2014).

Dediu, L., Coatu, V., Damir, N. Effect of some waterborne pharmaceuticals on fish health. Scientific Papers. Series D. Animal Science, 2022. 65(2).

Feiner, M. et al. Sublethal effects of the beta-blocker sotalol at environmentally relevant concentrations on the New Zealand mudsnail Potamopyrgus antipodarum. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 33(11), 2510–2515 (2014).

Hernando, M. D. et al. Analysis by liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry and acute toxicity evaluation for β-blockers and lipid-regulating agents in wastewater samples. J. Chromatogr. A 1046(1–2), 133–140 (2004).

Delahaut, V. et al. Toxicity and bioaccumulation of Cadmium, Copper and Zinc in a direct comparison at equitoxic concentrations in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) juveniles. PLoS ONE 15(4), e0220485 (2020).

Cunha, D. L., de Araujo, F. G. & Marques, M. Psychoactive drugs: occurrence in aquatic environment, analytical methods, and ecotoxicity: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24(31), 24076–24091 (2017).

Świacka, K. et al. Toxic effects of NSAIDs in non-target species: a review from the perspective of the aquatic environment. Environ. Pollut. 273, 115891 (2021).

Godoy, A. A., Kummrow, F. & Pamplin, P. A. Z. Occurrence, ecotoxicological effects and risk assessment of antihypertensive pharmaceutical residues in the aquatic environment: A review. Chemosphere 138, 281–291 (2015).

Selvakumar, R., Guhananthan, A. & Palanisami, T. Recent advances in micropollutant removal and mitigation from water using three dimensional adsorbent materials. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 34, 100475 (2023).

Wilson, M. M. et al. Lagrangian coherent structures in low Reynolds number swimming. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 21(20), 204105 (2009).

Hamed, M., et al. Assessment the effect of exposure to microplastics in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) early juvenile: I. blood biomarkers. Chemosphere, 2019; 228: 345–350.

Dacie, J. V., Lewis, S. M.: Practical Haematology. London Churchill Livingstone. Day, H. I., Young, E., Helfrich, M. (1980) An evaluation of a whole-blood platelet counter. Am) C/in Pathol. 73, 1975. 588(593): p. 59–65.

Sayed, A.E.-D.H. & Moneeb, R. H. Hematological and biochemical characters of monosex tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus, Linnaeus, 1758) cultivated using methyltestosterone. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 72, 36–42 (2015).

Doumas, B. T., Watson, W. A. & Biggs, H. G. Albumin standards and the measurement of serum albumin with bromcresol green. Clin. Chim. Acta 31(1), 87–96 (1971).

Köhler, G., Milstein, C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature, 1975. 256(5517): 495–497.

Tietz, N. W., Berger, S. Fundamentals of clinical chemistry. 1976.

Weissman, M. & Klein, B. Evaluation of glucose determinations in untreated serum samples. Clin. Chem. 4(5), 420–422 (1958).

Rej, R., Horder, M. Aspartate aminotransferase. Methods of enzymatic analysis, 1983. 3: p. 416–433.

Bhuvaneshwari, N. B., A study of serum iron profile and liver enzymes in subclinical hypothyroidism. 2019.

Moss, D. W. Alkaline phosphatase isoenzymes. Clin. Chem. 28(10), 2007–2016 (1982).

Hørder, M., et al. International federation of clinical chemistry, scientific division committee on enzymes: Approved recommendation on IFCC methods for the measurement of catalytic concentration of enzymes. Part 7. IFCC method for creatine kinase (ATP: creatine N-phosphotransferase, EC 2.7.3.2). Eur. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem., 1991. 29(7): p. 435–56.

Dito, W. R. Lactate Dehydrogenase: A Brief Review. Clin. Enzymol. 1979. 1.

Hamed, M. et al. Antioxidants and molecular damage in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) after exposure to microplastics. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 14581–14588 (2020).

Nishikimi, M., Rao, N. A. & Yagi, K. The occurrence of superoxide anion in the reaction of reduced phenazine methosulfate and molecular oxygen. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 46(2), 849–854 (1972).

Livingstone, D. R. Contaminant-stimulated reactive oxygen species production and oxidative damage in aquatic organisms. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 42(8), 656–666 (2001).

Sayed, A.E.-D.H., Mahmoud, U. M. & Mekkawy, I. A. Erythrocytes alterations of monosex tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus, Linnaeus, 1758) produced using methyltestosterone. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 42(1), 83–90 (2016).

Sayed, A.E.-D.H., El-Sayed, Y. S. & Ali, H. Hepatoprotective efficacy of Spirulina platensis against lead-induced oxidative stress and genotoxicity in catfish, Clarias gariepinus. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 143, 344–350 (2017).

Collins, A. R. The comet assay for DNA damage and repair: principles, applications, and limitations. Mol. Biotechnol. 26(3), 249–261 (2004).

Hidaka, M. et al. Cell lines derived from a Medaka radiation-sensitive mutant have defects in DNA double-strand break responses. J. Radiat. Res. 51(2), 165–171 (2010).

Końca, K. et al. A cross-platform public domain PC image-analysis program for the comet assay. Mutat. Res./Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagenesis 534(1–2), 15–20 (2003).

Chen, H. & Luo, D. Application of haematology parameters for health management in fish farms. Rev. Aquac. 15(2), 704–737 (2023).

Sayed, A. E. D. H. et al. Apoptosis and morphological alterations after UVA irradiation in red blood cells of p53 deficient Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes). J. Photochem. Photobiol., B 161, 1–8 (2016).

Soliman, H. A. M. et al. Protective effects of a novel pyrazolecarboxamide derivative against lead nitrate induced oxidative stress and DNA damage in Clarias gariepinus. Environ. Pollut. 247, 678–684 (2019).

Witeska, M. Erythrocytes in teleost fishes: A review. Zool. Ecol. 23(4), 275–281 (2013).

Docan, A., Grecu, I. & Dediu, L. Use of hematological parameters as assessment tools in fish health status. J. Agrolimentary Process. Technol. 24, 317–324 (2018).

Anderson, J. L. & Prystowsky, E. N. Sotalol: An important new antiarrhythmic. Am. Heart J. 137(3), 388–409 (1999).

Koubová, A. et al. Metabolome adaptation and oxidative stress response of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) to altered water pollution levels. Environ. Pollut. 303, 119117 (2022).

Hodges, V. M. et al. Pathophysiology of anemia and erythrocytosis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 64(2), 139–158 (2007).

Bardhan, A. et al. Visualization of poikilocytosis as an emerging erythrocytic biomarker for fish health assessment. Anim. Res. One Health 2(2), 136–157 (2024).

Sayed, A.E.-D.H., Oda, S. & Mitani, H. Nuclear and cytoplasmic changes in erythrocytes of p53-deficient medaka fish (Oryzias latipes) after exposure to gamma-radiation. Mutat. Res./Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 771, 64–70 (2014).

Pandey, K. B., Rizvi, S. I. Biomarkers of oxidative stress in red blood cells. Biomedical Papers of the Medical Faculty of Palacky University in Olomouc, 2011. 155(2).

Gwaltney-Brant, S. Blood and bone marrow toxicity biomarkers, in Biomarkers in toxicology 2019, Elsevier. p. 401–411.

Yang, Y. et al. Histopathological, hematological, and biochemical changes in high-latitude fish Phoxinus lagowskii exposed to hypoxia. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 47, 919–938 (2021).

Mahmood, M. A. Effect of hazelnut oil on hematological parameters and liver histopathological changes induced by naproxen in local male mice. Kufa J. Vet. Med. Sci. 15(2), 34–41 (2024).

Manrique-Moreno, M. et al. Effects of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug naproxen on human erythrocytes and on cell membrane molecular models. Biophys. Chem. 147(1), 53–58 (2010).

Boodhan, S. & Friedman, J. N. Naproxen-induced anemia and hypoalbuminemia in a 16-month-old child. Clin. Pediatr. 48(1), 96–98 (2008).

Youhnovski, N. et al. Volumetric absorptive microsampling combined with impact-assisted extraction for hematocrit effect free assays. Bioanalysis 9(22), 1761–1769 (2017).

Fairbanks, V. F. et al. Measurement of blood volume and red cell mass: re-examination of 51Cr and 125I methods. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 22(2), 169–186 (1996).

Siddeswaran, S., Umamaheswari, S., Ramesh, M. Toxicity assessment of acetylsalicylic acid to a freshwater fish Cyprinus carpio: haematological, biochemical, enzymological and antioxidant responses. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Water: Emerging Contaminants and Ecological Impact, 2020: p. 191–215.

Lohner, T. W., et al. Assessment of tolerant Sunfish populations (Lepomis sp.) inhabiting selenium-laden coal ash effluents: 1. Hematological and population level assessment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2001; 50(3): 203–216.

Fletcher, G. L. The effects of capture," stress," and storage of whole blood on the red blood cells, plasma proteins, glucose, and electrolytes of the winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus). Can. J. Zool. 53(2), 197–206 (1975).

Saravanan, M., Kumar, K. P. & Ramesh, M. Haematological and biochemical responses of freshwater teleost fish Cyprinus carpio (Actinopterygii: Cypriniformes) during acute and chronic sublethal exposure to lindane. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 100(3), 206–211 (2011).

İspir, Ü. & Şahin, A. Hematological parameters in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, after exposure to ibuprofen. Hydrobiol. Res. 1(1), 1–9 (2023).

Li, Z.-H. et al. Acute toxicity of carbamazepine to juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss): Effects on antioxidant responses, hematological parameters and hepatic EROD. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 74(3), 319–327 (2011).

Brucka-Jastrzębska, E. & Protasowicki, M. Effects of cadmium and nickel exposure on haematological parameters of common carp, Cyprinus carpio L. Acta Ichthyol. Piscat. 35(1), 29–38 (2005).

Magnadottir, B. Immunological control of fish diseases. Mar. Biotechnol. 12, 361–379 (2010).

George, A. D. I., Akinrotimi, O. A. & Nwokoma, U. K. Haematological changes in African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) exposed to mixture of atrazine and metolachlor in the laboratory. J. FisheriesSciences. Com 11(3), 48 (2017).

Akinrotimi, O. A., Aranyo, A. A. & Ibemere, I. F. Physiological response in Tilapia guineensis subjected to handling stress. Adv. Agric. Sci. Eng. Res. 1(2), 34–39 (2011).

Akinrotimi, O. A. et al. Effects of direct transfer to fresh water on the haematological parameters of Tilapia guineensis Bleeker, 1862. Anim. Res. Int. 7(2), 1199–1205 (2010).

Tort, L. Stress and immune modulation in fish. Dev. Comput. Immunol. 35(12), 1366–1375 (2011).

Ribas, J. L. C., Zampronio, A. R., Silva De Assis, H. C. Effects of trophic exposure to diclofenac and dexamethasone on hematological parameters and immune response in freshwater fish. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2016; 35(4), 975–982.

Meng, Z., Qin, G. & Zhang, B. DNA damage in mice treated with sulfur dioxide by inhalation. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 46(3), 150–155 (2005).

Ziemann, C. et al. Genotoxicity testing of sulfur dioxide (SO2) in a mouse bone marrow micronucleus test complemented with hematological endpoints. Mutat. Res./Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 697(1–2), 38–46 (2010).

Andreeva, A. M. The strategies of organization of the fish plasma proteome: With and without albumin. Russ. J. Mar. Biol. 45, 263–274 (2019).

Bjarnason, I., Thjodleifsson, B. Gastrointestinal toxicity of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: the effect of nimesulide compared with naproxen on the human gastrointestinal tract. Rheumatology (Oxford, England), 1999. 38(suppl_1): p. 24–32.

Lewis, J. H. NSAID-induced hepatotoxicity. Clin. Liver Dis. 2(3), 543–561 (1998).

Zhao, H. et al. Hepatoprotective effects of zinc (II) via cytochrome P-450/reactive oxygen species and canonical apoptosis pathways after arsenite waterborne exposure in common carp. Chemosphere 236, 124869 (2019).

Van der Oost, R., Beyer, J. & Vermeulen, N. P. E. Fish bioaccumulation and biomarkers in environmental risk assessment: A review. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 13(2), 57–149 (2003).

Gallego-Ríos, S. E., Peñuela, G. A. & Martínez-López, E. Updating the use of biochemical biomarkers in fish for the evaluation of alterations produced by pharmaceutical products. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 88, 103756 (2021).

Jain, S., Gautam, V., Naseem, S. Acute-phase proteins: As diagnostic tool. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci., 2011. 3(1).

Oliveira, J., Oliva-Teles, A., Couto, A. Tracking biomarkers for the health and welfare of aquaculture fish. Fishes (MDPI AG), 2024. 9(7).

Henneberger, L. et al. Trout and human plasma protein binding of selected pharmaceuticals informs the fish plasma model. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 41(3), 559–568 (2022).

De Smet, H., Blust, R. & Moens, L. Absence of albumin in the plasma of the common carp Cyprinus carpio: Binding of fatty acids to high density lipoprotein. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 19(1), 71–81 (1998).

Matthee, C. et al. Factors determining the susceptibility of fish to effects of human pharmaceuticals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57(24), 8845–8862 (2023).

Mikula, P. et al. Long-term dietary exposure to the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs diclofenac and ibuprofen can affect the physiology of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) on multiple levels, even at “environmentally relevant” concentrations. Sci. Total Environ. 917, 170296 (2024).

Peñuela, G. A. & Martínez-López, E. Enzymatic activity changes in striped catfish Pseudoplatystoma magdaleniatum, induced by exposure to different concentrations of ibuprofen and triclosan. Chemosphere 271, 129399 (2021).

Abdel-Khalek, A. A., Badran, S. R. & Marie, M.-A.S. The effective adsorbent capacity of rice husk to iron and aluminum oxides nanoparticles using Oreochromis niloticus as a bioindicator: Biochemical and oxidative stress biomarkers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 23159–23171 (2020).

Ramesh, M. et al. Primary stress responses of common carp, Cyprinus carpio, exposed to copper toxicity. Acta Ichthyol. Piscat. 37, 81–85 (2007).

Cicik, B., EngiN, K. The effects of cadmium on levels of glucose in serum and glycogen reserves in the liver and muscle tissues of Cyprinus carpio (L., 1758). Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2005. 29(1): p. 113–117.

Tunçsoy, M. Impacts of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on serum parameters and enzyme activities of Clarias gariepinus. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 106(4), 629–636 (2021).

Mozanzadeh, M. T. et al. The effect of salinity on growth performance, digestive and antioxidant enzymes, humoral immunity and stress indices in two euryhaline fish species: Yellowfin seabream (Acanthopagrus latus) and Asian seabass (Lates calcarifer). Aquaculture 534, 736329 (2021).

Ghelichpour, M. et al. Plasma antioxidant and hepatic enzymes activity, thyroid hormones alterations and health status of liver tissue in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) exposed to lufenuron. Aquaculture 516, 734634 (2020).

Sun, Z. et al. Effects of dietary dandelion extract on the growth performance, serum biochemical parameters, liver histology, and immune and apoptosis-related genes expression of hybrid grouper (Epinephelus lanceolatus♂× Epinephelus fuscoguttatus♀) at different feeding period. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 120, 280–286 (2022).

Baldissera, M. D. & Baldisserotto, B. Creatine kinase activity as an indicator of energetic impairment and tissue damage in fish: A review. Fishes 8(2), 59 (2023).

Magouz, F. et al. Dietary Bacillus subtilis relieved the growth retardation, hepatic failure, and antioxidative depression induced by ochratoxin A in Thinlip Mullet (Liza ramada). Aquacult. Rep. 22, 100984 (2022).

Janssen, L. et al. Muscle toxicity of drugs: when drugs turn physiology into pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 100(2), 633–672 (2020).

Fitori, A. et al. Effects of some heavy metal pollutants on liver and kidney performance of mullet captured from Tubruk harbor comparing to Umm Hufayan lagoon. DYSONA-Life Sci. 1(2), 83–90 (2020).

Mona, S. Z. et al. Effect of mercuric oxide toxicity on some biochemical parameters on African cat fish Clarias gariepinus present in the River Nile. Life Sci. J. 8(1), 363–368 (2011).

Lackner, R. “Oxidative stress” in fish by environmental pollutants, in Fish ecotoxicology1998, Springer. p. 203–224.

Jia, R. et al. Chronic exposure of hydrogen peroxide alters redox state, apoptosis and endoplasmic reticulum stress in common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Aquat. Toxicol. 229, 105657 (2020).

Koner, D. et al. Molecular characterization of superoxide dismutase and catalase genes, and the induction of antioxidant genes under the zinc oxide nanoparticle-induced oxidative stress in air-breathing magur catfish (Clarias magur). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 47, 1909–1932 (2021).

Bagnyukova, T. V. et al. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense responses by goldfish tissues to acute change of temperature from 3 to 23°C. J. Therm. Biol 32(4), 227–234 (2007).

Lushchak, V. I. & Bagnyukova, T. V. Effects of different environmental oxygen levels on free radical processes in fish. Comput. Biochem. Physiol. B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 144(3), 283–289 (2006).

Ighodaro, O. M. & Akinloye, O. A. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): Their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alexandria J. Med. 54(4), 287–293 (2018).

Sinha, A. K. et al. Anti-oxidative defences are modulated differentially in three freshwater teleosts in response to ammonia-induced oxidative stress. PLoS ONE 9(4), e95319 (2014).

Halliwell, B., Gutteridge, J. M. C. Free radicals in biology and medicine 2015: Oxford university press.

Sies, H. Oxidative stress: Oxidants and antioxidants. Exp. Physiol.: Translat. Integr. 82(2), 291–295 (1997).

Lushchak, V. I. Environmentally induced oxidative stress in aquatic animals. Aquat. Toxicol. 101(1), 13–30 (2011).

Farag, M. R. & Alagawany, M. Erythrocytes as a biological model for screening of xenobiotics toxicity. Chem. Biol. Interact. 279, 73–83 (2018).

Aziz, S., Abdullah, S. Evaluation of toxicity induced by engineered CuO nanoparticles in freshwater fish, Labeo rohita. Turk. J. Fisher. Aquat. Sci. 2023. 23(8).

Hamed, M. et al. Microplastics-induced eryptosis and poikilocytosis in early-juvenile nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Front. Physiol. 12, 742922 (2021).

Stoev, S. N. et al. Naproxen in pain and inflammation: A review. Int J Pharm Phytopharm Res 11(1), 142–148 (2021).

Goldkind, L. & Laine, L. A systematic review of NSAIDs withdrawn from the market due to hepatotoxicity: lEssons learned from the bromfenac experience. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 15(4), 213–220 (2006).

Moon, W.-K., Atique, U. & An, K.-G. Ecological risk assessments and eco-toxicity analyses using chemical, biological, physiological responses, DNA damages and gene-level biomarkers in Zebrafish (Danio rerio) in an urban stream. Chemosphere 239, 124754 (2020).

Parolini, M. Toxicity of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) acetylsalicylic acid, paracetamol, diclofenac, ibuprofen and naproxen towards freshwater invertebrates: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 740, 140043 (2020).

Artuso, T. et al. Mechanism of DNA cleavage mediated by photoexcited non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Photochem. Photobiol. 54(2), 205–213 (1991).

Yan, S. et al. Carbamazepine at environmentally relevant concentrations caused DNA damage and apoptosis in the liver of Chinese rare minnows (Gobiocypris rarus) by the Ras/Raf/ERK/p53 signaling pathway. Environ. Pollut. 270, 116245 (2021).

Rocco, L. et al. Evaluation of zebrafish DNA integrity after exposure to pharmacological agents present in aquatic environments. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 73(7), 1530–1536 (2010).

Gonzalez-Rey, M. et al. Occurrence of pharmaceutical compounds and pesticides in aquatic systems. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 96(1–2), 384–400 (2015).

Limbu, S. M. et al. Chronic exposure to low environmental concentrations and legal aquaculture doses of antibiotics cause systemic adverse effects in Nile tilapia and provoke differential human health risk. Environ. Int. 115, 205–219 (2018).

Eniola, J. O. et al. A review on conventional and advanced hybrid technologies for pharmaceutical wastewater treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 356, 131826 (2022).

Marcon, M. et al. Prevention of unpredictable chronic stress-related phenomena in zebrafish exposed to bromazepam, fluoxetine and nortriptyline. Psychopharmacology 233(21), 3815–3824 (2016).

Schaefer, I. C., et al. The side-by-side exploratory test: a simple automated protocol for the evaluation of adult zebrafish behavior simultaneously with social interaction. Behav. Pharmacol., 2015. 26(7 Special Issue Pharmacological Approaches To The Study Of Social Behaviour - Part 2: Social Modulat).

Näslund, J. et al. Naproxen affects multiple organs in fish but is still an environmentally better alternative to diclofenac. Aquat. Toxicol. 227, 105583 (2020).

Priyadarshinee, S., Umamaheswari, S. & Ramesh, M. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) naproxen-induced hepatotoxicity in a freshwater fish Labeo rohita. Water Air Soil Pollut. 234(1), 28 (2023).

Kwak, K. et al. Chronic toxicity and endocrine disruption of naproxen in freshwater waterfleas and fish, and steroidogenic alteration using H295R cell assay. Chemosphere 204, 156–162 (2018).

Brozinski, J.-M. et al. The anti-inflammatory drugs diclofenac, naproxen and ibuprofen are found in the bile of wild fish caught downstream of a wastewater treatment plant. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47(1), 342–348 (2013).