Abstract

The size distribution of minor earthquakes, characterized by a power-law decay (b-value), sometimes indicates the hazard information of major earthquakes. Studies show that the b-value reflects the stress level and proximity of the fault failure condition. However, the mechanisms are difficult to determine. This study proposes an additional proximity indicator that is ratio of stacked seismic moment tensor to total moment release in a volume. The ratio indicates efficiency of inelastic strain due to seismic moment release by earthquakes, being close to the strength of the medium based on the Mohr diagram and Coulomb failure condition. We examined the b-value and efficiency variations in pre- and post-seismic activities of the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake sequence. The weighted b-value distribution based on efficiency captured the initiation point of the Kumamoto earthquake. Thus, utilizing both b-value and efficiency can improve earthquake alerts and disaster mitigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Earthquakes occur when stress builds up to a level equal to the strength of the fault. According to the Coulomb failure criteria1, strength is controlled by medium properties such as the frictional coefficient, pore-fluid pressure, and loaded normal stress on the fault. Therefore, finding the location where stress is concentrated and/or in close proximity to the failure condition in a medium is critical for evaluating potential earthquake occurrences.

Observational studies using natural earthquake catalogs have shown that the b-value2, which represents the power decay of the earthquake magnitude–frequency distribution, can help determine the stress level in the seismogenic zone. Studies have shown an inverse relationship between the b-value and differential stress3,4,5. Moreover, laboratory studies investigating the relationship between the state of stress, small earthquakes (i.e., acoustic emissions), and rock failures (large earthquakes) have confirmed that the b-values decreases with increasing differential stress and proximity to rock failure6,7,8. Supporting evidence has been found based on natural earthquake observations. Studies have reported that large earthquakes were initiated when low b-values of preceding earthquakes were observed9. These findings also demonstrate that both the differential stress and proximity to large earthquake failures affect the b-value. On the other hand, according to laboratory experiment6, the b-value reveals different dependency of loading rate and small stress level compared with peak stress level (i.e., strength of the major fault). This implies that the b-value is affected by several factors, suggesting b-value distribution alone is not always sufficient to evaluate the state of stress and proximity of large earthquakes.

Recent study10 has reported that b-value takes small value toward to a critical condition of failure defined by Coulomb Failure condition based of high precision focal mechanism dataset. It means that medium under the critical condition (high proximity) could easily generate large earthquake. Figure 1a shows schematic illustration of the relation between proximity and a Mohr diagram1 with Coulomb Failure condition. Based on this result, we introduce an additional parameter to express the proximity and attempt to evaluate criticality of large earthquake occurrence by analysis of seismic activity.

(a) Schematic image of proximity plotting on a Mohr diagram for a stress condition with maximum (σ1), moderate (σ2), and minimum (σ3) principal stresses. Solid line indicate Coulomb Failure condition with friction coefficient μ, normal stress σn, and pore fluid pressure p0. (b) Schematic illustration of two fault distributions in a volume. σ1, σ2, and σ3 indicate maximum, medium, minimum principal stress axes, respectively. Small segment in the volume shows earthquake fault. Blue rectangle indicates large earthquake fault future ruptured. (c) Mohr diagram plot for the Case 1 and 2. Fault planes located in green area of the diagram can slip under the stress condition.

Proximity parameter for large earthquake

In order to introduce the proximity, we consider two cases of seismic activity around large earthquake fault in a volume: (1) most earthquakes occur on optimal planes to the stress field, and (2) many earthquakes have focal mechanisms showing non-optimal (unfavorable) fault slips (Fig. 1b). Optimal direction can be defined by failure criteria seen in “Methods” section. Case 2) has been reported for seismic activity in volcanic and hydrothermal areas11,12. The two cases correspond to conditions for dry and high fluid pressure circumstances of medium, respectively. Under a stress condition, inelastic deformation due to seismic activity progresses to totally release and re-distribute shear stress in the volume, although the seismic activity pattern in Case 1 is different from that in Case 2. Figure 1b,c shows a schematic illustration of these conditions and distribution range of event occurring both conditions on Mohr circle, respectively. The difference in the two cases is that more earthquakes (i.e., seismic moment release) are required in Case 2 than in Case 1 to create the same amount of inelastic strain due to earthquakes (i.e., equivalent to elastic stress release, see “Methods” section). Inelastic strain increment is responsible to stress build up on large earthquake fault by stress loading from outside because it creates redistribution of stress in the medium and stress concentration on the large fault.

In order to investigate the seismic activity pattern, we introduce a parameter to evaluate inelastic strain efficiency, which is the ratio of the stacked seismic moment tensor magnitude to the total scalar moment for earthquakes in a region. The ratio (Mstk/M0) is defined as:

where \({M}_{ij}^{k}\) and \({M}_{0}^{k}\) are the seismic moment tensors (i, j = 1–3) and the scalar moment of the kth event among all the K events, respectively. The magnitude of the summed tensor, \(\left|\sum_{k}^{K}{M}_{ij}^{k}\right|\), is calculated by computing the norm of the tensor defined as \(\sqrt{{{\sum }_{i,j=1}^{3}\left(\sum_{k}^{K}{M}_{ij}^{k}\right)}^{2}/2}\)). The efficiency was high for Mstk/M0, which was close to 1. Cases 1 and 2 correspond to high and low Mstk/M0 values, respectively. A medium with a deformation property Mstk/M0 close to 1 is thought to be able to generate large earthquake faulting, as shown by examples where a large earthquake slip preferentially occurs in the direction of maximum shear stress13,14. Therefore, Mstk/M0 can be interpretated as proximity of large earthquake occurrence. Shear stress acting on a fault plane oriented in the maximum shear stress direction is the largest among all planes, which allows for the generation of a large slip on the plane owing to the large releasable strain energy.

The b-value obtained from the frequency–magnitude distribution of an earthquake is affected by both the differential stress and the criticality of the stress to large failure. The Mstk/M0 is therefore related to the proximity of the stress condition for large failures. Therefore, utilizing both the b-value and Mstk/M0 may help identify locations where the potential for earthquake occurrence is high.

Application to pre- and post-seismic activity of the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake (M7.3) sequence

Data and setting

We estimated the b-value and Mstk/M0 in the hypocentral area of the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake sequence. The 2016 Kumamoto earthquake (M7.3) occurred on April 16, 2016, in Kumamoto Prefecture, Kyushu Island, Japan (hereafter, referred to as the Kumamoto EQ). The sequence started with the largest foreshock (M6.5) 28 h prior to the main shock. The earthquakes were distributed on and around two active faults (the Futagawa and Hinagu faults). Studies15,16 estimated the co-seismic fault behavior of the main shock and largest foreshock. These earthquakes occurred in a heterogeneous stress field17,18. A study18 reported heterogeneous stress field resulted in various slip directions of the main shock, in accordance with the Wallace–Bott hypothesis19,20, and that a large slip area occurred in the fault direction favorable to the stress field. In addition, a small differential stress of approximately 10 MPa was estimated, indicating a weakening of the crustal strength in this area. In addition, heterogeneity in earthquake frequency and size distributions are found21.

We used event data with magnitudes greater than 0 (M > 0) from the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) catalog to estimate the b-value from January 1, 2000 to March 19, 2023. However, seismic moments were based on a catalog from 2000 until October 2020 by routinely determined by Kyushu University and the previous study22 because of focal mechanism quality. The focal mechanism catalog was determined using data from additional seismic stations in the target region for the JMA catalog and is highly precise. Focal mechanisms were determined using the HASH algorithm23. Only events of M > 2 were used for the seismic moment estimation because of their accuracy. The seismic moment tensor was estimated based on the empirical relationship between the moment tensor, earthquake magnitude, and focal mechanism24. The lists M > 2 events in both catalogs are consistent with each other.

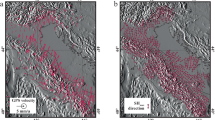

The b-value and Mstk/M0 were estimated for the spatial blocks distributed in the target area. The block size was 0.05° horizontally and 10 km in the depth range. To smooth the block division, we shifted the block distribution by half the block size to the northeast and estimated it again. We set two periods for the analysis: (1) January 2000 to April 14, 2016 (before the largest foreshock of M6.5 occurred) and (2) after the main shock on April 16, 2016. The lower limit of the number of events in the spatial block was 50 for the b-value and 20 for Mstk/M0. Figure 2 shows the epicenter and tension axis distributions used in this study for both periods.

Epicenter and P-axis distribution in the Kumamoto area of Kyushu, Japan. Pink segments show the fault traces of active faults. Triangles show the locations of active volcanoes. (A) Epicenter distribution before the largest foreshock (M6.5) and after the main shock (M7.3). Dots indicates epicenters. Stars show events with magnitude > 5.0. White and green segments are on-shore fault traces of the Futagawa–Hinagu fault system and the co-seismic fault of the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake, respectively. (B) P-axis distribution of events. Blue and green segments show axes with dip angles of < 45 and > 45, respectively. The black segment shows the co-seismic fault of the main shock.

The b-value has been estimated for many regions and shows both spatial and temporal variations. Here, it was estimated as the power decay of the frequency–magnitude distribution. The standard method for estimating b was followed25,26,27. We set a constant magnitude range to estimate the b-value. The range is from a magnitude of 0.6 to 4. The lower limit of the magnitude (Mc) was determined by applying the ZMAP software28 to both data periods. We selected Mc = 0.6, which approximates to the higher limit of the spatial distributions of Mc determined by ZMAP (Fig. S1). The upper limit was set at a magnitude of four based on the spatial bin size because the typical fault length of an event with M4 might be significantly smaller than the bin size.

b-value and Mstk/M0 distribution

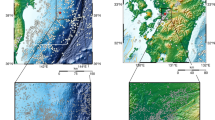

The spatial distributions of both the b-value and efficiency (Mstk/M0) are shown in Fig. 3. The distribution is plotted for each depth range (0–10 km, 10–20 km) and the period (1 and 2). The symbol in color corresponds to the b-value, as shown in the color scale in Fig. 3, with a size proportional to the Mstk/M0 value. Colors are clipped at the upper and lower bands in the scale bar, as shown in Fig. 3. As discussed, both the differential stress and criticality of the strength of the medium affect the b-value, while the criticality reflects Mstk/M0. Therefore, in Fig. 3, a large symbol with a hot color indicates criticality, which could be associated with the likelihood of large earthquakes. A separate plot of b and Mstk/M0 is shown in Fig. S2. The b-values have a wide range, from < 0.6 to > 1.0. Low b-value regions in period 1 can be found around earthquake faults (Hinagu and Futagawa faults). This trend is similar to that reported by other study36. In particular, low b-value areas were found in the deep range (10–20 km) rather than in the shallower range. A block reveals a low b-value with a large Mstk/M0 immediately beside the initiation point of the main shock (depth = 12 km). This indicates that the hypocenter was located at a high stress level, close to the failure condition. Moreover, it suggests that plotting the b-value against Mstk/M0 can help identify the critical conditions for large earthquake generation, particularly in regions characterized by low b-values.

Weighted b-value distribution by Mstk/M0. The lower right of each panel shows a close-up of the hypocentral area of the Kumamoto earthquake. (A,B) represent data obtained before the main shock in depth ranges of 0–10 and 10–20 km. (C,D) are same as (A,B) except the data used are after the main shock. The red star indicates the hypocenter of the main shock. The open star in close-up figure shows the M6.5 hypocenter. Triangles show the locations of active volcanos. Purple segments display active fault traces.

In period 2, blocks with low b-values were not only found around the entire earthquake fault but also in the extension of the fault. Notwithstanding the wide distribution of low b-values, the Mstk/M0 weighted distribution highlighted high stress and criticality at the extension. This might indicate that the differential stress at the extension increased owing to co-seismic slip and approach the critical condition.

Discussion

Figure 4 shows the b-value and Mstk/M0 distribution with standard error along the Hinagu Fault for every period and depth range. The error was estimated by boot-strap resampling for the dataset. The efficiencies in period 1 were close to 1 in the low b-value blocks. However, despite showing a low b-value, some blocks were not highly efficient and were therefore under the critical conditions for large failures under high-stress conditions. During period 2, Mstk/M0 decreased significantly in the deeper regions of the earthquake faults. It dropped to below 0.8 in most blocks, whereas it was over 0.9 before the earthquake. This suggests that earthquakes slip occurred on fault planes with various orientations due to strength decline. This can be interpreted as fluid-intrusion and weakening fault strength associated with the main shock occurrence, as suggested by the fault valve model29. Another reason for the low Mstk/M0 value is the existence of a strong heterogeneous stress field. We estimated Mstk/M0 in a spatial block and expected that the assumption of a homogeneous stress field would not be broken. However, the stress field could be strongly perturbed around the co-seismic fault owing to slip on the fault. This resulted in a low Mstk/M0 in the estimation. In practice the stress field around the earthquake fault after the earthquake exhibits larger heterogeneity than that in the pre-earthquake period22. Therefore, low Mstk/M0 around the fault may be attributed not only to medium under non-critical condition but also to heterogeneous stress field. However, small-scale stress field perturbations may preclude rupture growth over block-scale sizes. Therefore, Mstk/M0 can be considered an indicator of a large failure. A resistivity study30 in this region found that the hypocenter of the main shock was located at the lower bound of the high resistivity area. This implies that stress relaxation can happen before the main shock at just below the hypocenter owing to a weak strength medium with low resistivity. Then, the medium at the hypocenter could be under high stress and easily reach the critical condition. The resistivity also exhibited a high value at the low b and high proximity area pointed out in period 2. These results suggest that the area could be an asperity for a forthcoming earthquake because the high-resistivity medium is considered to be relatively high strength.

We evaluated the inelastic strain efficiency by calculating the ratio between the magnitude of the stacked moment tensor and the total scalar moment. Then, we examined simple cases in which the ratio changed with the frictional coefficient variation and with the stress ratio in the medium. In this exercise, we considered a medium containing isotropic, randomly oriented, preexisting fault planes. The faults satisfied the condition that generates slip. To meet the condition, the position on the Mohr circle, calculated from the geometrical relationship between the fault direction and the stress tensor, must lie within the area bounded by the Mohr circle and the CFF segment. The CFF segment is defined by (3), as shown in Fig. 1. Thus, fault planes that satisfy the CFF condition with fluid pressures ranging from P0 to P can slip in this situation. Assuming that each fault releases the same seismic moment, we calculated the stacked moment tensor, its magnitude, and the total scalar moment. We observed that the ratio decreased with an increasing upper limit of P for various frictional coefficients and stress ratios, as shown in Fig. S4. In particular, the maximum value for a low friction coefficient was approximately 1. However, the maximum value decreased for high frictional coefficients, although the observed results in the previous section were higher than those of the simulation. This can be attributed to two factors: (1) the frictional coefficient is small in the Kumamoto area, and (2) more events have low P values than high P values. As previously mentioned, the observed results show that the moment of release for low P values is large; therefore, cause 2 is reasonable. In the case of a small stress ratio, the decline was not obvious in the simulation. Hence, Mstk/M0 may decrease because of cause 2.

Employing a parameter similar to that used in this study, a slip tendency analysis31 has been proposed. The slip tendency is defined as the ratio of the shear stress to the effective normal stress, which is determined for every fault plane under a known stress tensor. The tendency distribution was plotted on a Mohr circle, similar to the Mstk/M0 value. Therefore, if the stress field is known and the fault plane can be identified, the average slip tendency variation shows a pattern similar to that of the Mstk/M0 distribution. However, in the analysis of natural earthquakes, fault plane identification and stress field estimation can be challenging. In contrast, Mstk/M0 analysis from the perspective of the inelastic strain efficiency of a volume is not required to choose the fault plane from the focal mechanism solution and to fix the stress tensor, which can provide information about the criticality of a large failure.

We propose Mstk/M0 for evaluating proximity to the failure condition under an assumption of isotropic distribution of the pre-existing fault. However, we note that Mstk/M0 values can involve bias in the case of anisotropic fault distribution. For instance, Mstk/M0 is 1 if all earthquakes have the same focal mechanism each other. This situation can arise when small earthquakes occur on just one large, very weak fault. This problem is also found in the stress tensor inversion by focal mechanism data. Careful discussion about hypocenter and focal mechanism distribution is required in order to avoid this issue. In our target area of Kumamoto, the earthquake distribution prior to the M6.5 (period 1) had no relation to the co-seismic fault geometry, meaning that the earthquake faults prior to its occurrence did not affect the small earthquakes. Therefore, the proximity evaluation for period 1 might be reliable; however, the possibility of unknown anisotropy exists. In addition, focal mechanism estimation error make the value decrease. In this study, the estimated Mstk/M0 for spatial bins distributed in a range of 0.6 to 1 had small estimation error for the parameters, as shown in Fig. 4.

In addition, there are constraints associated with applying the parameters to monitor the potential for large earthquake.

-

1.

Seismic Activity Requirement: The area surrounding the fault must exhibit small earthquake activity prior to the occurrence of a large earthquake.

-

2.

Parameter distribution: A low b-value and/or high Mstk/M0 should be prevalent across most of the earthquake fault.

-

3.

Period and Scale length: Strength weakening and stress concentration around the hypocenter should not shorter time and spatial bin scale..

Clarifications:

-

Seismic Activity Absence: An area lacking seismic activity cannot be deemed safe, as the absence of small earthquakes does not necessarily indicate a lack of stress accumulation.

-

Parameter Implications: A previous study10 indirectly demonstrated that a medium exhibiting a high Mstk/M0Mstk/M0 ratio, as defined in this paper, is in a critical state. However, this study did not elaborate on the mechanisms by which large earthquakes occur. It is plausible that the generation of significant earthquakes requires an extensive spatial area to be in a critical condition. As shown in Fig. 3 and Fig. S2, high Mstk/M0 and low b-values are observed around the earthquake fault.

-

Stress and Strength Considerations: The analysis in this study was performed under the assumption that the characteristics of seismic activity in the target area reflect the static (long-term) stress field. However, earthquake triggering can be attributed to short-term changes in stress concentration or strength weakening. Therefore, both temporal and spatial scales need to be considered for detectability, as short-term or short-wavelength changes in stress and strength are difficult to detect.

Conclusions

In this study, we showed that the inelastic strain caused by small earthquakes is related to the proximity of a medium to the failure condition. The ratio of the stacked moment tensor magnitude to the total scalar moment can be adopted as an indicator of proximity. By applying this approach to hypocenter and focal mechanism data in the hypocentral area of the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake sequence, we captured the initiation point of the main shock as a low b-value with high proximity. Utilizing both the b-value and the proximity of seismic activity, we revealed a method for earthquake potential evaluation. This may contribute to the mitigation of earthquake hazards. For further study, application for various areas with high seismic activity is necessary based on precise seismic moment tensor estimation. We propose a semi-empirical method based on seismic data. However, mechanical modeling using observation data of elastic and inelastic deformation, and stress different conditions is needed.

Methods

Inelastic strain due to small earthquakes

Earthquake faulting is an inelastic phenomenon that occurs within an elastic medium. This means that while the Earth’s crust generally behaves like a flexible solid, earthquake faults cause sudden breaks and shifts, creating localized zones of inelastic deformation. To describe this process mathematically, we use a distributed moment tensor, which represents how the stress is released in the medium due to fault movement. Now, imagine many small faults scattered randomly throughout a given volume of rock. If these faults are evenly distributed and their sizes are much smaller than the total volume, their combined movement leads to inelastic strain in the region. A pioneering study32 proposed a relationship between the inelastic strain and the released seismic moment tensor density. First, the relationship between the seismic moment density tensor and the seismic moment is given by:

where mij and Mkij are the ij-components of the released seismic moment density and seismic moment tensor of the kth earthquake, respectively and K is the number of earthquakes. ΔV is the volume over which these earthquake occur. Then, this inelastic strain \({\varepsilon }_{ij}^{i}\) is related to the seismic moment density tensor through the compliance tensor Cijkl:

This relationship is referred to as an inelastic strain due to a “stress glut”33,34.

Next, we considered the conditions under which each fault slip occurs. Fault slip happens when the shear stress acting on a fault reaches the fault’s strength. To express the stress conditions in the volume, we used the Mohr diagram, which plots the relationship between absolute normal stress and shear stress. In the diagram, three circles were defined with the following diameters: one representing the maximum (σ1) and minimum (σ3) principal stresses, another representing σ1 and medium (σ2) stresses, and the third representing σ2 and σ3 stresses. Faults with any orientation were plotted within the area surrounded by these circles (Fig. 1). For each event, the location on the circle was determined by the shear and normal stresses, which were calculated based on the geometrical relationship between the stress tensor and the fault orientation. According to the Coulomb failure function (CFF), the strength (τf) of a preexisting fault plane is defined as:

where \(\upmu , {\upsigma }_{\text{n}},\, \text{and}\, P\) are the friction coefficient, normal stress on the fault, and pore-fluid pressure, respectively.

When a segment defined by the CFF touches the Mohr circle, only a fault in a particular direction (i.e., the optimal direction) can slip, and the fluid pressure reaches the minimum P0. The rising pore fluid pressure P shifts the CFF segment to the right of the diagram, resulting in the generation of earthquakes on non-optimal fault planes11. Under random variation in fluid pressure with a maximum value of P inside the volume, a fault slip may be generated on a fault plotted in the upper left area of a segment defined by the CFF (Fig. S1).

The two cases in Fig. 1 correspond to conditions for P close to P0 and a higher P. Under stress conditions, inelastic deformation progresses to release shear stress in the volume, although the seismic activity pattern in Case 1 is different from that in Case 2. Figure 1 shows a schematic illustration of these conditions.

Efficiency of accumulating inelastic strain in a volume

A fault slip on a fault plane loaded with maximum shear stress (i.e., plotted on top of the Mohr diagram, where the fault-normal vector rotates 45° from directions σ1 to σ3) can release stress in the volume effectively. For example, two earthquakes with moment tensor (Mij) identical in shape to the stress tensor in the volume can release stress by generating inelastic strain \(2{C}_{ijkl}{M}_{ij}/\Delta V\). However, if the earthquakes occur on planes rotated by a certain angle from the previous one, or on the conjugate in the σ1 direction, the resulting inelastic strain will be smaller. For instance, slip planes with rotation of 45 + θ and − 45 − θ from σ1 to σ3 create only \((2{\text{cos}\left(\theta \right)}^{2}-2{\text{sin}\left(\theta \right)}^{2}){C}_{ijkl}{M}_{ij}/\Delta V\), even though the released tensor shape is the same as the stress tensor (see SI). In Case 2, where multiple fault planes with large θ are involved, the efficiency of inelastic strain accumulation is lower compared to Case 1. Based on elastoplastic theory, a medium macroscopically deforms to follow deviatoric stress; as such, both cases reveal the same amount of stress release with the same stress tensor shape but different behaviors during deformation. Therefore, the efficiency of the inelastic deformation by stacking moment tensors can be characterized35.

The friction coefficient of the fault can influences the Mstk/M0 value. We found that Mstk/M0 decreased as the friction coefficient increased. This was because the efficiency of the stacking moment tensor decreased, as described above (i.e., a case with a large θ). However, a rise in pore fluid pressure causes a strong decline in the Mstk/M0 value for any frictional coefficients, as described in the “Discussion” section, indicating that Mstk/M0 can be adopted as an indicator of the efficiency.

We note that, as discussed, the b-value is affected by both the differential stress and the criticality of the stress to large failure. However, separating these two factors is difficult. The efficiency indicator Mstk/M0 depends on the relative position of the Mohr circle and is therefore related to the criticality of the stress condition for large failures rather than the differential stress.

Data availability

The hypocenter location data from the JMA used in this study were obtained from http://www.data.jma.go.jp/svd/eqev/data/bulletin/index_e.html. The focal mechanism data are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15099759. The HASH algorithm used to determine the focal mechanism is available at https://www.usgs.gov/node/279393. The ZMAP program developed by Wiemer (2001) is available at http://www.seismo.ethz.ch/en/research-and-teaching/products-software/software/ZMAP/). Figures were plotted using GMT5 (https://www.soest.hawaii.edu/gmt/). Code for calculate Mstk/M0 and b-value from catalog is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10388142.

References

Jaeger, J. C., Cook, N. G. W. & Zimmerman, R. W. Fundamentals of Rock Mechanics 4th edn. (Blackwell Ltd, 2007).

Gutenberg, B. & Richter, C. F. Frequency of earthquakes in California. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 34(4), 185–188. https://doi.org/10.1785/BSSA0340040185 (1944).

Scholz, C. H. On the stress dependence of the earthquake b-value. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42(5), 1399–1402. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL062863 (2015).

Schorlemmer, D., Wiemer, S. & Wyss, M. Variations in earthquake-size distribution across different stress regimes. Nature 437(7058), 539–542. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04094 (2005).

Spada, M., Tormann, T., Wiemer, S. & Enescu, B. Generic dependence of the frequency–size distribution of earthquakes on depth and its relation to the strength profile of the crust. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40(4), 709–714. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL054198 (2013).

Bolton, D. C., Shreedharan, S., Rivière, J. & Marone, C. Frequency magnitude statistics of laboratory foreshocks vary with shear velocity, fault slip rate, and shear stress. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126(11), e2021JB022175. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JB022175 (2021).

Goebel, T. H. W., Schorlemmer, D., Becker, T. W., Dresen, G. & Sammis, C. G. Acoustic emissions document stress changes over many seismic cycles in stick-slip experiments. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40(10), 2049–2054. https://doi.org/10.1002/grl.50507 (2013).

Scholz, C. H. The frequency-magnitude relation of microfracturing in rock and its relation to earthquakes. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 58(1), 399–415. https://doi.org/10.1785/BSSA0580010399 (1968).

Schorlemmer, D. & Wiemer, S. Earth science: Microseismicity data forecast rupture area. Nature 434(7037), 1086. https://doi.org/10.1038/4341086a (2005).

Matsumoto, S., Iio, Y., Sakai, S. & Kato, A. Strength dependency of frequency–magnitude distribution in earthquakes and implications for stress state criticality. Nat. Commun. 15, 4957. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49422-7 (2024).

Terakawa, T., Zoporowski, A., Galvan, B. & Miller, S. A. High pressure fluid at hypo-central depths in the l’Aquila region inferred from earthquake focal mechanisms. Geology 38(11), 995–998. https://doi.org/10.1130/G31457.1 (2010).

Terakawa, T., Miller, S. A. & Deichmann, N. High fluid pressure and triggered earthquakes in the enhanced geothermal system in Basel, Switzerland. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 117(B7), B07305. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JB008980 (2012).

Angelier, J. Tectonic analysis of fault slip data sets. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 89(B7), 5835–5848. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB089iB07p05835 (1984).

Michael, A. J. Determination of stress from slip data: Faults and folds. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 89(B13), 11517–11526. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB089iB13p11517 (1984).

Asano, K. & Iwata, T. Source rupture processes of the foreshock and mainshock in the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake sequence estimated from the kinematic waveform inversion of strong motion data. Earth Planets Space 68(1), 147. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-016-0519-3279 (2016).

Asano, K. & Iwata, T. Revisiting the source rupture process of the mainshock of the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake and implications for the generation of near-fault ground motions and forward-directivity pulse. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 111(5), 2426–2440. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120210047 (2021).

Matsumoto, S. et al. Spatial heterogeneities in tectonic stress in Kyushu, Japan and their relation to a major shear zone. Earth Planets Space 67(1), 172. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-015-0342-8 (2015).

Matsumoto, S. et al. Prestate of stress and fault behavior during the 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake (M7.3). Geophys. Res. Lett. 45(2), 637–645. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL075725 (2018).

Wallace, R. E. Geometry of shearing stress and relation to faulting. J. Geol. 59(2), 118–130. https://doi.org/10.1086/625831 (1951).

Bott, M. H. P. The mechanics of oblique slip faulting. Geol. Mag. 96(2), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756800059987 (1959).

Mitsuoka, A. et al. Spatiotemporal change in the stress state around the hypocentral area of the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake sequence. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 125(9), 9. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JB018515 (2020).

Nanjo, K. Z., Izutsu, J., Orihara, Y., Kamogawa, M. & Nagao, T. Changes in seismicity pattern due to the 2016 Kumamoto earthquakes identify a highly stressed area on the Hinagu fault zone. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46(16), 9489–9496. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GL083463 (2019).

Hardebeck, J. L. & Shearer, P. M. A new method for determining first-motion focal mechanisms. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 92(6), 2264–2276. https://doi.org/10.1785/0120010200 (2002).

Matsumoto, S., Nishimura, T. & Ohkura, T. Inelastic strain rate in the seismogenic layer of Kyushu Island, Japan. Earth Planets Space 68(1), 207. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-016-0584-0 (2016).

Aki, K. Maximum likelihood estimate of b in the formula log N = a − bM and its confidence limits. Bull. Earthq. Res. Inst. Univ. Tokyo 43, 237–239 (1965).

Bender, B. Maximum likelihood estimation of b-values for magnitude grouped data. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 73(3), 831–851. https://doi.org/10.1785/BSSA0730030831 (1983).

Utsu, T. Representation and analysis of the earthquake size distribution: A historical review and some new approaches. Pure Appl. Geophys. 155(2–4), 509–535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s000240050276 (1999).

Wiemer, S. A software package to analyze seismicity: ZMAP. Seismol. Res. Lett. 72(3), 373–382. https://doi.org/10.1785/gssrl.72.3.373 (2001).

Sibson, R. H. Rupture nucleation on unfavorably oriented faults. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 80(6), 1580–1604 (1990).

Aizawa, K. et al. Electrical conductive fluid-rich zones and their influence on the earthquake initiation, growth, and arrest processes: Observations from the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake sequence, Kyushu Island, Japan. Earth Planets Space 73, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-020-01340-w (2021).

Morris, A., Ferrill, D. A. & Brent Henderson, D. B. Slip-tendency analysis and fault reactivation. Geology 24(3), 275–278. https://doi.org/10.1130/0091-7613(1996)024%3c0275:STAAFR%3e2.3.CO;2 (1996).

Kostrov, V. V. Seismic moment and energy of earthquakes, and seismic flow of rock. Izvestia Earth Phys. 1, 23–40 (1974).

Aki, K. & Richards, P. G. Quantitative Seismology—Theory and Methods Vol. 1 (H. Freeman, 1980).

Ichihara, M., Kusakabe, T., Kame, N. & Kumagai, H. On volume-source representations based on the representation theorem. Earth Planets Space 68(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-016-0387-3 (2016).

Matsumoto, S. Method for estimating the stress field from seismic moment tensor data based on the flow rule in plasticity theory. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43(17), 8928–8935. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL070129 (2016).

Nanjo, K. Z. et al. Seismicity prior to the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake. Earth Planets Space 68, 187. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-016-0558-2 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff and students of Kyushu University and the University of Tokyo, who maintain the seismic stations, for their work in obtaining good quality seismic data. We also used seismic data from the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) and Hi-net. We used the Generic Mapping Tools available at http://gmt.soest.hawaii.edu/home to plot the maps and results. This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan under its Second Earthquake and Volcano Hazards Observation and Research Program (Earthquake and Volcano Hazard Reduction Research).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M. carried out entire design of this study, the data processing, analysis for micro-earthquakes and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matsumoto, S. LARGE earthquake proximity indicated by seismic moment efficiency and frequency-number distribution of small earthquakes. Sci Rep 15, 17389 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01595-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01595-x