Abstract

A recent parallel-opposed 3D-conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) study in mice compared dose escalation (boost) in hypoxic (pO2 ≤ 10 torr) and non-hypoxic tumor subvolumes. They found a hypoxic boost led to significantly greater (p < 1e-4) tumor control probability than an equivalent non-hypoxic boost. We imported imaging and treatment data from this study for 31 SCC7 squamous carcinoma murine leg tumor cases—16 hypoxic boost and 15 non-hypoxic boost plans into a commercial treatment planning system for preclinical radiotherapy. Treatments were retrospectively recalculated with a fast Monte Carlo dose engine. We replanned cases with 3-field IMRT using an analogous uncertainty budget as 3D-CRT. Comparing both treatment groups, the hypoxic boost treatments had a significantly higher hypoxic fraction receive the boost prescription as planned in 3D-CRT (p < 1e-4) and IMRT (p < 1e-4). Surprisingly, retrospective 3D-CRT non-hypoxic boost treatments had a significantly lower non-hypoxic fraction receive the boost prescription (p < 1e-4). 3D-CRT non-hypoxic boost also substantially underdosed the entire tumor between 48–68 Gy compared to the “equivalent” hypoxic boost. In IMRT, the non-hypoxic volume receiving boost prescription was significantly higher in the non-hypoxic boost (p = 0.0215) and dosing in the entire tumor was identical between boost groups. This study displays IMRT’s potential to advance the quality of preclinical dose painting studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In radiation therapy, dose painting is an advanced approach to planning therapeutic dose distributions beyond a homogeneously prescribed conformal target dose to improve clinical outcomes. Dose painting entails scaling the prescribed irradiation dose to subvolumes within the target volume, based on quantitative molecular imaging features1. From imaging, tumor subvolume phenotype is assigned to dictate the corresponding prescribed dose level. The rationale for this comes from the variation in cellular radiosensitivity among differing tumor microenvironments, which is commonly measured in vitro through clonogenic assays of irradiated cells at different doses2. For instance, hypoxic tissue has been known to be more radioresistant, so treatment plans with homogenous dose distributions designed for non-hypoxic targets may fail due to the survival of hypoxic subregions3. To account for the influence of oxygenation on radiosensitivity, oxygen-guided radiotherapy (OG-RT) prescribes dose based on discretized or continuous tumor oxygenation levels, with the goal of improving the therapeutic ratio1,4.

The merit of OG-RT should be assessed in preclinical studies, but performing preclinical OG-RT, and more generally, preclinical dose painting, has been fettered mainly by the ability to miniaturize radiation treatment technologies to the scale of a rat or mouse models (~ 5 × or ~ 15 × smaller in the linear dimension, respectively). The use of clinical platform complicates preclinical studies. The size of a preclinical models relative to the build-up region of clinical MV photon beams may require the use of bolus and the relatively large penumbras can restrict the ability to boost large regions within the tumor. In Trani et al. 2015, volumetric modulated arc therapy plans using 6 MV photon beams redistributed dose in rats with a left flank tumor to 30% of the tumor with the highest or lowest fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) levels determined by positron emission tomography. High FDG regions correlated to radioresistant tumor regions and hypoxia5. They found no significant difference in tumor growth delay with dose redistribution at higher doses. Further, they observed detrimental effects at lower doses when redistributing dose to the high FDG region. However, they cautioned that FDG uptake might not be fully representative of hypoxia in their rat cancer model. A constant proportion of radioresistant cells between cases was assumed to allow tumor mean dose to remain constant between experimental groups. This approach meant a fixed volume received the higher dose unlike a variable volume in typical clinical approaches. Although this could cause treatment failure if the radioresistant volume exceeded 30%, this was also essential in their study to enable the comparison between dose redistribution groups6,7.

Recent innovations in small animal radiotherapy of image-guided irradiators, functional imaging, and beam modulation via motorized variable rectangular collimators (MVCs) or 3D-printed blocks have enabled dose painting in a preclinical irradiation platform8,9,10,11,12,13. As an example, Donche et al. 2022 developed a MATLAB-based automated workflow to deliver 20 Gy base dose with 16 beams and 8 Gy boost dose with 40 beams to glioblastoma tumors in rats using the MVCs of a preclinical irradiator14. OG-RT via retrofitting a preclinical irradiator with conformal aperture holder for beam modulation has demonstrated in mouse preclinical tumor models, for the first time (Epel et al. 2019) and now across 3 preclinical tumor models (Gertsenshteyn et al. 2023), the benefits of hypoxic-based dose escalation in mammalian in vivo tumor model. Studies quantified tumor oxygenation by electron paramagnetic resonance oxygen imaging (EPROI) and administered a locally increased (aka boost) dose to one of two regions: either hypoxic or non-hypoxic (where the threshold for hypoxia was defined as a partial pressure of oxygen less than or equal to 10 torr). The studies ensured equal integral dose between the two groups by controlling for aperture area, with the intention that any difference between the groups is due to the prescription location, not simply presence, of the boost dose. Results found significantly (p < 0.0001) improved local tumor control probability of hypoxic boost over an equivalent non-hypoxic boost group11,15.

These three studies7,11,15 illustrate a unique feature of preclinical dose painting studies to rigorously test the benefit of dose escalation to different tumor subvolumes by equalizing dose in the whole tumor volume over some parameter. In contrast, clinical trials for hypoxia-guided radiotherapy can only compare dose escalation in hypoxic subvolume to the whole-tumor boosted or non-boosted standard treatment16,17,18,19. With rodent-scale preclinical intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) delivery systems, animal radiotherapy can better mimic clinical radiotherapy’s capability to deliver multiple target dose levels via simultaneous integrated conformal boosts to ensure adequate organ sparing and also improve the construction of robust radiobiological studies to understand how to integrate the tumor biology into clinical radiotherapy decision-making12,13,20. The subsequent in vivo experiments will be valuable to study how to configure dose painting regimens based on cellular and biochemical information.

In the Gertsenshteyn et al. 2023 study, authors expanded the hypoxic margins to form parallel-opposed conformal apertures (shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2b) to account for imaging and treatment uncertainty. Image registration and treatment planning used an in-house MATLAB toolbox called ArbuzGUI11,21. The inclusion of margins allowed for adequate dose fall off to separate boost dose inside (hypoxic plan) from dose outside (non-hypoxic/oxygenated plan) the hypoxic subvolume. However, they noted that the approach limited the size of the targetable part of the non-hypoxic subvolume and required censoring candidate mice with a hypoxic subvolume larger than 42% of the entire tumor. Furthermore, from the beam’s-eye-view (BEV), this approach increased the fraction of beam intensity sub-elements (bixels) targeting non-hypoxic regions in the hypoxic boost and decreased the fraction of non-hypoxic regions exposed in the non-hypoxic boost. It also reassigned bixels outside of the projected tumor into the non-hypoxic tumor boost to achieve an equal integral dose. This was after optimizing beam angle for hypoxia compactness to minimize non-hypoxic collateral by sampling five angles evenly spaced apart15.

3D-CRT OG-RT Experiment Design in Gertsenshteyn et al. 2023. Illustrates the design of A) the hypoxic boost apertures with a 1.2 mm margin around the projected hypoxia outline added and B) the non-hypoxic boost apertures with a 0.6 mm margin around the projected hypoxia outline subtracted. Oxygenation is shown by color map of the EPR image. (Reproduced with permission. Fig. 3 in Gertsenshteyn et al.15).

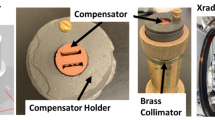

Treatment plan overview. A) illustrates the retrospective 48 Gy base dose for 15–20% local tumor control probability of SCC7 tumor (note experimental lead shielding to protect organs at risk was not modeled in TPS), B) depicts the retrospective 13 Gy boost dose to hypoxic or non-hypoxic subvolumes for 95–99% local tumor control probability (at 61 Gy) and the margin added around the projected hypoxia outline to the design 3D-CRT apertures accounting for imaging and treatment uncertainty (delivered experimentally using 3D-printed tungsten-doped PLA blocks), C) presents the replanning of boost treatments with 3-field IMRT with 1 mm bixels at isocenter and the isotropic expansion used during inverse optimization to account for uncertainty analogously (which could be delivered via 3D-printed copper-doped PLA compensators and tungsten trimmers12 or an analogous beam modifying device13,20). See Supplementary Fig. S1 for treatment plan implementation in µ-RayStation 8B.

To examine these limitations of the parallel-opposed 3D-conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT), we imported imaging and treatment data for 31 murine leg tumor treatment cases from Gertsenshteyn et al. 2023—16 hypoxic boost plans and 15 non-hypoxic (oxygenated) boost plans into a preclinical treatment planning system. We retrospectively recalculated delivered dose distributions using a fast GPU Monte Carlo dose engine22. To explore the benefit of IMRT over 3D-CRT for preclinical dose painting, we replanned cases using 3-angle IMRT boost treatments. The three angles were equally spaced and fixed. Importantly, we accounted for treatment uncertainty by equivalent isotropic expansions of the hypoxic subvolume rather than 2D margin expansions of the BEV conformal apertures in 3D-CRT. To our knowledge, this is the first retrospective analysis of the 3D dose distributions from a dose painting study in small animals and IMRT planning with a commercial treatment planning system specifically for small animals. By evaluating the dose distributions in small animal tumors determined by inverse planning rather than simply reporting the dose to the tumor from forward planning, we are moving closer to the clinical radiotherapy paradigm. This is crucial in evaluating the fidelity of treatment groups to the underlying experimental question, especially for preclinical dose painting studies.

Material and methods

Retrospective planning of 3D-CRT experiment

We imported imaging and treatment data from 31 mice with SCC7 squamous cell carcinoma leg tumors into µ-RayStation 8B (RaySearch Laboratories, Stockholm, Sweden), a Monte Carlo-based preclinical treatment planning system (TPS), previously used to model the small animal irradiator X-RAD225 Cx and validated in murine cases22. The imaging data comprised registered T2-weighted MRI, EPROI, and CBCT for tumor segmentation, hypoxia segmentation (pO2 ≤ 10 torr), and treatment alignment, respectively. Treatment data included beam angles, beam-on times, isocenters, and conformal apertures. Experimental treatments consisted of 48 Gy base dose (to the whole tumor) delivered by parallel-opposed 35 mm circular beams, followed by a 13 Gy boost dose delivered with parallel-opposed 3D-conformal beams to the hypoxic boost region (the high-risk planning target volume, PTVHR) or non-hypoxic boost region (the low-risk planning target volume, PTVLR). These dose levels were based on a tumor control dose 50% study (TCD50). The 48 Gy (base dose) and 61 Gy (base plus boost dose) respectively should result in 15–20% and 95–99% local tumor control probability for SCC7 tumors15.

For boost treatment plans, we imported the BEV 3D-CRT conformal beam apertures into µ-RayStation as contours. In the hypoxic boost cases, these apertures included a margin of 1.2 mm around the projected hypoxia outline to account for positioning and image registration uncertainty and to ensure that a minimum of 98% of the hypoxic subvolume received the boost dose. Assuming margins of error are correctly estimated, 100% hypoxic fraction should be covered. In the non-hypoxic (oxygenated) boost cases, these contours subtracted a 0.6 mm margin around the BEV-projected hypoxia outline to account for the same uncertainty and prevent dose spillage into the hypoxic subvolume. Figure 1 illustrates the design of these treatment contours. The previous experiment equalized beam aperture area to ensure the same integral dose and contours were 3D-printed as beam apertures using tungsten-doped polylactic acid (PLA) filament. Gantry angle for boost treatments was optimized for hypoxic area compactness in BEV after sampling 5 equally-spaced gantry angles. More information about the experimental setup can be found in Gertsenshteyn et al.15. Note experimental lead shielding used to protect non-target (organs at risk) regions during the base dose was not modeled here.

Retrospective BEV analysis

Based on two parallel-opposed beam angles chosen for each case (optimized for hypoxia compactness), a BEV image was generated indicating the projected hypoxia outline, projected tumor depth, and conformal aperture (see Fig. 4C). The hypoxia and tumor segmentations were rotated in MATLAB as 3D Boolean arrays. The projected hypoxia outline and tumor depth were determined by summing along the beam axis dimension of the array. The conformal aperture, stored as a 2D Boolean array to generate the STL of the 3D-printed aperture, was unchanged and plotted as a contour onto the BEV image. Although beam divergence was not accounted for, BEV image in MATLAB was nearly identical to the BEV in µ-RayStation. The overlap between the projected hypoxia and tumor outline was calculated. Then, the same overlap was re-calculated using projected tumor depth as a weighting factor to understand how 2D apertures generated from the projected hypoxia outline are impacted by the variation of tumor in beam axis dimension (orthogonal to the BEV plane). Similarly, a 1.2 mm margin was added around the projected hypoxia outline and the overlap was re-calculated to assess dose spillage into the non-hypoxic region.

Inverse planning for IMRT

The µ-RayStation 8B treatment planning system was commissioned to perform IMRT for the X-RAD225 Cx small animal irradiator (Precision X-Ray Inc., North Branford, CT) through fluence optimization for 1 mm (at isocenter) bixels. 3D-printed compensators for small animal IMRT have been validated in-house for 5-angle deliveries with 1 mm bixels for hypoxic and non-hypoxic boost plans with an average gamma pass rate over 90% for composite deliveries at 3%/1 mm criteria using 3D-printed compensators12. Greater treatment fidelity can be achieved by also performing total variation regularization on beamlet intensity maps used to design these compensators23.

In both groups, objective functions penalized dose proportionally to the non-boosted planning target volume. Three evenly spaced beam angles (0°, 120°, 240°) were used for IMRT (i.e. no tumor-specific optimization of beam angles was performed) and the original 35 mm beams used for the base dose in the 3D-CRT were not changed. Previous work indicated three beam angles for IMRT was sufficient for significant dose conformity improvement from parallel-opposed 3D-CRT in preclinical dose painting24.

Isotropic expansion for analogous uncertainty budget

Instead of a margin added in the BEV, the hypoxic subvolume was isotropically expanded to determine PTVHR in the hypoxic boost cases and PTVLR in the non-hypoxic boost cases used for treatment plan optimization. For hypoxic boost, the PTVHR was defined as a 1.2 mm isotropic expansion of the hypoxic volume to mirror the 1.2 mm margin to the projected hypoxia outline in the hypoxic boost for 3D-CRT. The PTVHR was optimized and normalized to ensure 98% of the volume received at least 13 Gy and no more than 2% received greater than 15 Gy.

Accounting for non-hypoxic dose spillage from hypoxic boost

During the 3D-CRT retrospective study, a substantial portion of the non-hypoxic tumor volume was found to receive the boost dose even though the intention was to boost only the hypoxic volume. This led to a modification in IMRT planning for non-hypoxic boost cases for a fairer comparison between IMRT and 3D-CRT. To account for the dose spillage of hypoxic boost cases, non-hypoxic boost plans were optimized like hypoxic boost cases but with a dose spillage surplus factor (see Fig. 2c). The PTVLR was defined as the remaining non-hypoxic subvolume after subtracting a 0.6 mm isotropic expansion of the hypoxic volume from the overall tumor.

This operation was to mirror the subtraction of the projected hypoxia outline with a 0.6 mm margin in the non-hypoxic boost for 3D-CRT. On average, 78% of the total tumor received the boost dose in the hypoxic 3D-CRT boost. Of this 78%, only 13% represented the hypoxic-equivalent volume. Thus, the dose spillage surplus factor was 65%, or the non-hypoxic-equivalent volume receiving boost dose in a hypoxic boost case. Optimization was then performed so that an equivalent absolute volume of the PTVLR received boost dose as 78% of the total tumor for that case. For plan practicality, this variable percent of the PTVLR was capped at 98%. The goal was to match the dose spillage from the 3D-CRT hypoxic boost into the non-hypoxic subvolume in the design of the IMRT non-hypoxic boost plan. This would demonstrate the benefit of IMRT over 3D-CRT to preferentially boost the non-hypoxic boost volume and account for hypoxic boost dose spillage (which was greater in the 3D-CRT than IMRT).

The other constraint was analogous to that of the hypoxic boost, where no more than 2% of the PTVLR received greater than 15 Gy. Note, there was not a significant difference between hypoxic and non-hypoxic boost cases in total tumor and hypoxic volume.

Statistics

Treatment uncertainty performed by expanding margins of conformal beam apertures in the retrospective study was modeled by isotropically expanding the hypoxic subvolume an equivalent amount during IMRT replanning and treatment. All Monte Carlo dose calculations in µ-RayStation simulated enough photons so that dose calculation uncertainty was 1% or lower. Dose distributions and metrics were evaluated in hypoxic and non-hypoxic subvolumes. Statistical significance of dose metrics was calculated using an unpaired, two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test between different boost groups or paired, two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test between same boost groups, where p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.001 (**), and p < 1e-4 (***) is denoted on the graphs.

Results

Retrospective analysis of parallel-opposed 3D-CRT

No significant difference (p = 0.338) between the total integral dose between the hypoxic and non-hypoxic boost groups was observed (Fig. 3A). However, a significant difference (p < 1e-4) was observed in the percent fraction of the overall tumor, hypoxic, and non-hypoxic volumes that received at least 61 Gy between the hypoxic boost and non-hypoxic boost groups, which represented the TCD 95–99% for SCC7 tumors (Fig. 3B-D). No significant difference between the absolute volume of the hypoxic (p = 0.572) and overall tumor volume (p = 0.741) between hypoxic and non-hypoxic boost groups was observed (Fig. 3E). A significant difference was observed in the absolute boosted subvolume receiving 61 Gy favoring (p < 0.001) the non-hypoxic boost group and absolute target volume receiving 61 Gy strongly favoring (p < 1e-4) the hypoxic boost group (Fig. 3E). Note BTV and NBTV respectively represent the hypoxic and non-hypoxic subvolume in the hypoxic boost, and the converse for non-hypoxic boost.

Retrospective 3D-CRT dose statistics. A) illustrates the integral dose calculated by average dose in the segmentation times the segmentation’s volume, B-D) shows the percentage of each subvolume receiving at least the base + boost prescription dose of 61 Gy, E) presents the absolute volume of the hypoxic, overall tumor, boosted target volume receiving at least 61 Gy, and total target volume receiving at least 61 Gy. Note imaging and treatment occurred when tumor sizes were between 0.225 cc and 0.45 cc measured by calipers according to the protocol in Gertsenshteyn et al.15, but the volume measurements listed here represent the volume in the segmentation after imaging and shape-based interpolation onto a higher resolution dose grid (0.3 mm isotropic voxels) in the treatment planning system. Level of significance is denoted by * (p < 0.05), ** (p < 0.001), and *** (p < 1e-4).

Retrospective BEV analysis

No significant difference was observed in the area of the tumor or hypoxic segmentation in the BEV between hypoxic and non-hypoxic boost groups (Fig. 4A). However, a significant difference (p < 1e-4) was observed after weighting overlap by tumor depth in the BEV, increasing the tumor-hypoxic percent overlap (Fig. 4B).

Retrospective BEV metrics. A) illustrates the area of the hypoxic region and tumor in the BEV, B) demonstrates the difference in overlap before and after weighting for the projected tumor thickness in the BEV, C) present two cases where the hypoxic projection covers more than half the tumor in the BEV after optimizing beam angle for hypoxia compactness, D) the overlap in the high-risk planning target area (PTAHR) and tumor in the BEV. Note the PTAHR was area covered after a 1.2 mm margin around hypoxic projection.

Example cases where the hypoxic region is in regions of high tumor depth are presented in Fig. 4C. The average overlap between hypoxic and tumor projections in the BEV was 35.8% ± 12.5% (s.d.). The increase in BEV hypoxic-tumor overlap when weighting for tumor depth was 9.6% ± 4.0%. Without considerations of tumor depth, a 1.2 mm margin to the hypoxic projection in the BEV, which can be considered analogously as the high-risk planning target area (PTAHR) for a 3D-conformal aperture, overlapped the tumor on average of 56.1% ± 21.3% (Fig. 4D).

Field IMRT plan analysis

A significant difference was not observed between the integral dose in the two target volumes (p = 0.654) and the overall percentage of the target volume receiving at least 61 Gy (p = 0.741) between hypoxic and non-hypoxic boost groups (Fig. 5A-B). The difference between percent of the hypoxic volume receiving at least 61 Gy was significant, strongly favoring (p < 1e-4) the hypoxic boost group (Fig. 5C). There was a significant difference in the absolute hypoxic volume receiving at least 61 Gy, favoring (p < 0.05) the hypoxic boost group, but the absolute volume of the non-hypoxic and entire tumor receiving at least 61 Gy was not significant between the two groups (Fig. 5D).

IMRT dose statistics. A) illustrates the integral dose of the target volume between boosted groups, B-C) show the percent fraction of the tumor and hypoxic receiving at least 61 Gy, D) illustrates the absolute boosted volume, non-boosted volume, and target volume receiving at least 61 Gy. Level of significance is denoted by * (p < 0.05), ** (p < 0.001), and *** (p < 1e-4).

To assess the impact of reducing treatment uncertainty, IMRT was replanned using a 0.2 mm isotropic expansion of the hypoxic subvolume for the PTVHR and subtraction of this PTVHR from the whole tumor for the PTVLR for inverse planning (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Comparison of preclinical 3D-CRT and IMRT planning

The relative DVH of the 3D-CRT experiment indicate a rapid fall-off of the entire target volume in the non-hypoxic boost relative to the hypoxic boost group between 48 to 68 Gy indicated by the solid lines (Fig. 6A). The relative DVH in the IMRT experiment shows close agreement of the entire target volume in the non-hypoxic boost and hypoxic boost across all doses (Fig. 6B).

Absolute DVH of the 3D-CRT experiment demonstrate a lower absolute volume receiving a dose around 51 Gy to 63 Gy in both the non-boosted and boosted target volumes (Fig. 7A). The absolute DVHs of the IMRT experiment remove this large discrepancy in the non-hypoxic region, but the differential in the hypoxic region between groups becomes narrower (Fig. 7B).

Results with a significance of p < 1e-4 between hypoxic and non-hypoxic boosts are bolded. 61 Gy represented the prescription dose level for the boosted target volume (BTV). Note BTV and NBTV respectively represent the hypoxic and non-hypoxic subvolume in the hypoxic boost, and the converse for non-hypoxic boost.

Discussion

As expected, the retrospective 3D-CRT plans delivered nearly zero dose to hypoxic subvolume in the non-hypoxic boost due to way conformal apertures were designed (Fig. 3C & 6A). However, this aperture construction led to a delivery of ≥ 61 Gy to a significantly greater fraction of both hypoxic and non-hypoxic volumes in the hypoxic boost (Fig. 3B-D). Although it is expected that the projected hypoxia outline in the beam’s eye view (BEV) will include some non-hypoxic regions, overlap weighted by tumor demonstrates how the projected hypoxia outline also co-located in the deepest regions of the tumor in the BEV (Fig. 4C). This fits with the phenotype of hypoxia being connected to aggressive tumor proliferation25. This geometry also matches observations from other functional imaging like Trani et al. 2015, where the lowest FDG uptake region being typically in the outer shell of the tumor and the highest FDG uptake region being the core of the tumor6,7.

This coupled with the added 1.2 mm margin in hypoxic boost beam apertures (Fig. 4B & 4D) led to a significantly larger overall target volume receiving at least 61 Gy in hypoxic boost than the non-hypoxic boost (Fig. 3E & 7A). However, there were some differences between the experiment and retrospective study. Regions of the tumor outside the normal HU range of the tissue (−250 to 450) that extended onto air or the high-Z polyvinyl siloxane cast used to immobilize the mouse leg were excluded from the PTV. This led to some apertures extending into regions where there was no hypoxic or tumor region in both groups. This is analogous to how clinically 3D fields used to treat breast cancer are sometimes expanded to treat air around the target to provide a buffer zone for uncertainty in the setup26.

Additionally, despite matching of treatment beam angles, isocenters, bed shifts, and aperture contours, some cases had margins that appeared to be slightly larger and smaller than 1.2 mm and 0.6 mm margins. Places where the margin was slightly larger along all boundaries may be due to a correction factor for 3D-printing over-extrusion after examining the code used to generate apertures. Yoon et al. 2022 highlighted the variation in shielding results of tungsten PLA prints based on different 3D-printing parameters like nozzle size, extrusion speed, and layer height27. This sensitivity is most likely augmented for printing finer details required in 3D-conformal apertures, and the previous study design from Epel et al. 2019 mentioned an underdosing of small disconnected hypoxic regions as much as 30% from film analysis.

Places were the margins appeared slightly smaller on one side and larger on the other than expected may be due to a deviation in treatment isocenter. Cases slightly larger on one side could be also from the experimental protocol. A local margin equal to an EPROI pixel (0.66 mm) was added when non-tumor hypoxia was observed directly adjacent to tumor hypoxia. It was believed that this was a EPROI resolution-limited case of tumor penetration beyond the borders seen in the MRI, similar to how the clinical target volume (CTV) includes the gross tumor volume (the tumor detectable in imaging) plus a margin for the subclinical tumor (the tumor not yet detectable in imaging or usual clinical tests)28. But after adding a 1.2 mm margin to the projected hypoxia outline, more than half the beam aperture overlapped with the projected tumor outline (Fig. 4D). This is without factoring for tumor depth, which also significantly increased the overlap between the projected hypoxia-tumor outlines in the BEV (Fig. 4B). Further, this was after optimization for hypoxia compactness across 5 evenly spaced angles11. So, despite some problems mentioned above during treatment planning, it became apparent the difficulty of parallel-opposed 3D-CRT to preferentially boost the hypoxic subvolume while equalizing dose spread across the overall target volume. The BEV metrics used here to assess the feasibility of the 3D-CRT technique could also be repurposed to optimize beam angle for dose painting, similar to the BEV “dosimetrics” developed in Pugachev et al. 2002 to speed up beam angle optimization in IMRT by rejecting poorly scoring angles29.

The uncertainty budget of a 2D margin added to an aperture was transposed to a 3D isotropic expansion for inverse planning. This 3D isotropic expansion is clinically analogous to the planning target volume determined from a margin applied to CTV to account for systematic and random error, typically derived from equations like the van Herk margin recipe30. Two questions need to be asked for preclinical dose painting. The first is the standard clinical question: does the planning target volumes provide sufficient coverage of the tumor (plus any boosted volumes) and avoidance of healthy structures? The second is unique to preclinical dose painting: what should be normalized to provide comparable experimental groups, or treatment parity?

For the 2D margin, Epel et al. 2019 and Gertsenshteyn et al. 2023 normalized integral dose (~ area of the conformal aperture) between treatment groups to preserve treatment parity. However, the work in this paper demonstrates the limitation of this approach, particularly in ensuring similar dose spread in the overall target volume between the hypoxic and non-hypoxic boost groups. Specifically, a lower absolute volume receiving dose from 51 to 63 Gy in the target volume (Fig. 7A) could significantly impact tumor control probability (TCP) due to the sigmoidal shape of the tumor control dose31. A difference in dose spread in the overall target volume between the hypoxic and non-hypoxic boost groups may lead to a false positive study supporting dose escalation.

To ensure treatment parity while inverse planning, Trani et al. 2015 fixed boosted volume at 30% of the total tumor volume6,7. However, this could lead to treatment failure in cases where the fraction of radioresistant cells exceeds 30% of the tumor. Epel et al. 2019 reported 85% of tumor hypoxia coverage failed to provide any significant treatment difference to a non-hypoxia boosted group11. Although Trani et al. 2015 is similar to Epel et al. 2019 and Gertsenshteyn et al. 2023 in the experimental hypothesis and design, substantial differences most likely explain the contradictory results, such as the different preclinical model (rat vs. mouse), energy range (MV vs. kV), functional imaging (PET vs. EPROI), treatment technique (VMAT with clinical MLCs vs. 3D-CRT with 3D-printed blocks), and the delineation of boosted volume (fixed percentage of highest or lowest FDG uptake vs. variable percentage based on oxygen partial pressure), and biological endpoint measured (tumor growth delay vs. local tumor control probability)6,7,11,15.

The approach in this paper to achieve treatment parity was to compensate for dose spillage into the non-hypoxic volume by the hypoxic boost into the non-hypoxic boost plan. Specifically, 3 field IMRT was designed to preferentially boost the hypoxic subvolume in the hypoxic boost group without boosting the whole tumor volume significantly more than the non-hypoxic boost group, which occurred in the retrospective parallel-opposed 3D-CRT (Fig. 3C-E, 6A, 7A). The results demonstrate a similar overall target volume fraction (Fig. 5B) and absolute volume (Fig. 5D) receiving 61 Gy, while maintaining the significant difference in the fraction (Fig. 5C) and absolute hypoxic subvolume (Fig. 5D) receiving 61 Gy between hypoxic and non-hypoxic boost groups. The difference in dose spread in the target volume is eliminated (Fig. 6B) and the absolute non-hypoxic volume on average now received a higher dose in the non-hypoxic boost group (Fig. 7B).

This approach assumes an unequal binary volume (of hypoxic and non-hypoxic), such that the boosting the smaller volume (the hypoxic) results in non-negligible boosting to the larger surrounding volume (the non-hypoxic). Part of this was due to the experimental protocol excluding mice with a hypoxic fraction greater than 42% from the study. For these 31 cases, the hypoxic volume was ~ 4-to-fivefold lower than the non-hypoxic volume. Second, this approach is more favorable for tumor geometries where the compensatory volume (non-hypoxic) is generally located in the tumor periphery. For this study, the non-hypoxic spillage from the 3D-CRT hypoxic boost was used to plan the IMRT non-hypoxic boost, so that the results could be comparable to the 3D-CRT non-hypoxic boost. However, 3D-CRT is most likely the worst-case scenario of non-hypoxic spillage for IMRT. In practice, a hypoxic boost plan could be generated with IMRT for that case to determine the dose spillage surplus factor for a non-hypoxic boost plan like in the 3D-CRT workflow11.

Using an analogous uncertainty budget, the IMRT hypoxic boost did reduce dose spillage in non-hypoxic volume, but not more than 10% on average (Table 1). A potential explanation for this is the boost dose coverage of the PTVHR forced a large fraction of the non-hypoxic volume to receive 13 Gy to account for all possible treatment uncertainty. Specifically, a 1.2 mm isotropic expansion of the hypoxic subvolume for the PTVHR increased overall tumor fraction boosted by roughly 50% relative to hypoxic fraction. Replanning with a 0.2 mm isotropic expansion suggests that smaller margins can improve preferential hypoxic boosting and separation in dose spread in the hypoxic subvolume between the hypoxic and non-hypoxic boost groups (Supplementary Fig. S2). An anisotropic expansion used typically to target subclinical lesions after post-operative treatments32 could be useful here to avoid normal tissue structures33 and reduce the boosted target volume34.

Even with 0.2 mm treatment uncertainty for IMRT, four cases in the non-hypoxic boost had more than half the hypoxic subvolume receive 61 Gy (Supplementary Fig. S2). Preliminary analysis did not reveal a correlation between number of discrete hypoxic regions and these outliers, but our previous work has identified a correlation between surface-area-to-volume-ratio and number of hypoxic regions to lower conformity index in hypoxic target volume in preclinical 3D-CRT and IMRT dose painting. The problem of multiple hypoxic volumes complicating dose painting is similar to the challenges faced in treatment of multi-target cases, thus similar approaches could be further investigated for preclinical dose painting like the benefit of single- vs. multi-isocenter treatments35, single isocenter with distinct optimization36, or optimizing single-isocenter selection37.

The rationale for a Monte Carlo dose engine for this work stems from this change in interactions from MV to kV range, which can lead clinical superposition-convolution dose calculations to underestimate dose up to threefold in and around high atomic Z regions like bone38. A full Monte Carlo simulation for IMRT in small animals should be performed to understand how well dose calculation algorithms used in inverse planning for preclinical IMRT handle heterogeneity, especially under orthovoltage conditions with a more dominant photoelectric effect that makes atomic composition more relevant in dose calculations39. There are also uncertainties related to the material assignment used for the Monte Carlo simulation40, particularly given the high-Z immobilization material around the mouse leg which will attenuate heavily and potentially scatter dose into the mouse.

Unlike patient-derived xenograft models, syngeneic and genetically-engineered models do not require immunodeficient mice41. All the animals in Gertsenshteyn et al. 2023 were syngeneic SCC7 squamous carcinomas15. It is unclear how non-targeted effects, like the bystander effect and abscopal effect, come into play for preclinical dose painting. For locoregional tumor studies, the abscopal effect will be negligible. The intratumoral dose distribution could also modulate the abscopal effect. For instance, Yasmin-Karim et al. 2022 targeted either the planning target volume with a larger field size (10 × 10 mm or 5 × 5 mm) or the gross tumor subvolume (GTV) with a smaller field size (3 × 3 mm) in one of two contralateral tumors. A greater abscopal effect was observed from targeting the GTV42, but more conformal preclinical dose painting could improve these types of studies on non-targeted effects.

The next step will be to connect planning dose metrics to treatment outcomes of mice over time, but experimental discrepancies first need to be resolved and healthy structures must be contoured to assess organ-sparing through other dose metrics like Paddick conformity index43. It is conceivable that the standardized optimization approach could also be improved by refining the objective function. Although fractionation in preclinical treatments does occur44, there has yet to be complete mirroring of clinical paradigm of combining fractionation with dose painting.

The translatability of any preclinical results depends on how well it mirrors clinical conditions. Any clinical criteria should be scaled down or transposed to the preclinical context. Biological endpoints measured can be especially important, where favorable studies based on tumor control probability are more likely to translate successfully into the clinic than studies based on tumor growth delay45. Although conventionally, translation is meant in the forward direction (i.e. extrapolating preclinical data to clinical situations), and new paradigm called reverse translation where initial findings from clinical trials are rigorously tested preclinically could be equally important. For instance, the clinical study by McWilliam et al. 2017 linked higher doses in a region at the base of the heart to significantly worse patient survival46. Using a mouse model, Ghita et al. 2020 corroborated the increased radiosensitivity at the heart base47. Through reverse translation, preclinical dose painting can directly study the known intra-organ radiosensitivity and lead to rapid translation into clinical protocols to limit late side effects. A more comprehensive evaluation of preclinical radiotherapy’s applications and next steps can be found in Verhaegen et al. 202348. This paper highlights the need for preclinical treatment planning (especially in dose painting experiments) and the capability of inverse planning with IMRT to improve the quality of preclinical studies.

Conclusion

Retrospective re-calculation of 31 preclinical oxygen-guided radiotherapy cases previously treated using parallel-opposed 3D-CRT validated the accurate delivery of preferential boost doses to the hypoxic subvolumes. Results also demonstrated the technical limitation of the approach in the underdosing of the non-hypoxic fraction and absolute volume in the non-hypoxic boost cohort relative to the hypoxic boost. This ultimately led to an underdosing of the overall target volume in non-hypoxic boost cases. Independent of these dose calculations, BEV analysis of the projected tumor-hypoxia outlines also demonstrated the limitations of preclinical 3D-CRT. Adding a 1.2 mm margin around the projected hypoxia outline for beam apertures caused more than half of the projected tumor outline to be covered on average, even after optimizing beam angle for hypoxia compactness. Further, the projected hypoxia outline co-located in the regions of greater tumor depth, leading to more non-hypoxic collateral in hypoxic boost apertures. Replanning using 3 field IMRT was performed with a similar non-hypoxic dose spillage surplus factor and treatment uncertainty budget, accomplished by equivalent isotropic expansion of the hypoxic subvolume to delineate high-risk and low-risk planning target volumes used in inverse planning. IMRT preserved preferential boost doses to the hypoxic subvolume in the hypoxic boost cohort while eliminating underdosing of the overall target volume in the non-hypoxic boost cases. Small animal IMRT demonstrates promise in equalizing dose distributions in the overall target volume between treatment groups. More broadly, designing robust preclinical dose painting studies will be important for studying biological and cellular responses to radiation to reduce clinical late side effects and improve tumor control probability.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files) or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bentzen, S. M. & Gregoire, V. Molecular imaging-based dose painting: a novel paradigm for radiation therapy prescription. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 21, 101–110 (2011).

El-Nachef, L. et al. Human Radiosensitivity and Radiosusceptibility: What Are the Differences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 7158 (2021).

Bouleftour, W. et al. A Review of the Role of Hypoxia in Radioresistance in Cancer Therapy. Med. Sci. Monit. 27, e934116 (2021).

Salem, A. Hypoxia-Targeted Dose Painting in Radiotherapy. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 33, 298–306 (2023).

Zegers, C. M. et al. In vivo quantification of hypoxic and metabolic status of NSCLC tumors using [18F]HX4 and [18F]FDG-PET/CT imaging. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 6389–6397 (2014).

Trani, D. et al. What level of accuracy is achievable for preclinical dose painting studies on a clinical irradiation platform. Radiat. Res. 183, 501–510 (2015).

Trani, D. et al. Preclinical assessment of efficacy of radiation dose painting based on intratumoral FDG-PET uptake. Clin. Cancer. Res. 21, 5511–5518 (2015).

Brown, K. H. et al. A scoping review of small animal image-guided radiotherapy research: Advances, impact and future opportunities in translational radiobiology. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 34, 112–119 (2022).

Ghita, M., Brown, K. H., Kelada, O. J., Graves, E. E. & Butterworth, K. T. Integrating small animal irradiators with functional imaging for advanced preclinical radiotherapy research. Cancers (Basel). 11, 170 (2019).

van Hoof, S. J., Verde, J. B. & Verhaegen, F. Dose painting by dynamic irradiation delivery on an image-guided small animal radiotherapy platform. Br. J. Radiol. 92, 20180744 (2019).

Epel, B. et al. Oxygen-Guided Radiation Therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 103, 977–984 (2019).

Redler, G. et al. Small Animal IMRT Using 3D-Printed Compensators. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 110, 551–565 (2021).

Yoon, S. W., Kodra, J., Miles, D. A., Kirsch, D. G. & Oldham, M. A method for generating intensity-modulated radiation therapy fields for small animal irradiators utilizing 3D-printed compensator molds. Med. Phys. 47, 4363–4371 (2020).

Donche, S. et al. Positron emission tomography-based dose painting radiation therapy in a glioblastoma rat model using the small animal radiation research platform. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/62560-v (2022).

Gertsenshteyn, I. et al. Absolute oxygen-guided radiation therapy improves tumor control in three preclinical tumor models. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 10, 1269689 (2023).

Welz, S. et al. Dose escalation to hypoxic subvolumes in head and neck cancer: A randomized phase II study using dynamic [18F]FMISO PET/CT. Radiother. Oncol. 171, 30–36 (2022).

Vera, P. et al. Phase II Study of a Radiotherapy Total Dose Increase in Hypoxic Lesions Identified by 18F-Misonidazole PET/CT in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma (RTEP5 Study). J. Nucl. Med. 58, 1045–1053 (2017).

Lee, N. Y. et al. Fluorine-18-labeled fluoromisonidazole positron emission and computed tomography-guided intensity-modulated radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: a feasibility study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 70, 2–13 (2008).

Servagi-Vernat, S. et al. Hypoxia-guided adaptive radiation dose escalation in head and neck carcinoma: a planning study. Acta Oncol. 54, 1008–1016 (2015).

Woods, K. et al. A sparse orthogonal collimator for small animal intensity-modulated radiation therapy part I: Planning system development and commissioning. Med. Phys. 46, 5703–5713 (2019).

Epel, B., Redler, G., Pelizzari, C., Tormyshev, V. M. & Halpern, H. J. Approaching Oxygen-Guided Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 876, 185–193 (2016).

Chiavassa, S. et al. Validation of the analytical irradiator model and Monte Carlo dose engine in the small animal irradiation treatment planning system µ-RayStation 8B. Phys. Med. Biol. 65, 035006 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Improving the efficiency of small animal 3D-printed compensator IMRT with beamlet intensity total variation regularization. Med. Phys. 49, 5400–5408 (2022).

Slagowski, J. M. et al. Compensator-based small animal IMRT enables conformal preclinical dose painting: application to tumor hypoxia. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.15684 (2025).

Li, Y., Zhao, L. & Li, X. F. Hypoxia and the Tumor Microenvironment. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 20, 15330338211036304 (2021).

Piruzan, E., Vosoughi, N., Mahdavi, S. R., Khalafi, L. & Mahani, H. Target motion management in breast cancer radiation therapy. Radiol. Oncol. 55, 393–408 (2021).

Yoon, M. S., Jang, H. M. & Kwon, K. T. Influence of parameters and performance evaluation of 3D-Printed tungsten mixed filament shields. Polymers (Basel). 14, 4301 (2022).

Burnet, N. G., Thomas, S. J., Burton, K. E. & Jefferies, S. J. Defining the tumour and target volumes for radiotherapy. Cancer Imaging 4, 153–161 (2004).

Pugachev, A. & Xing, L. Incorporating prior knowledge into beam orientation optimization in IMRT. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 54, 1565–1574 (2002).

van Herk, M., Remeijer, P., Rasch, C. & Lebesque, J. V. The probability of correct target dosage: dose-population histograms for deriving treatment margins in radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 47, 1121–1135 (2000).

Prior, P., Awan, M. J., Wilson, J. F. & Li, X. A. Tumor control probability modeling for radiation therapy of keratinocyte carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 11, 621641 (2021).

Dal Pra, A. et al. ESTRO ACROP guideline on prostate bed delineation for postoperative radiotherapy in prostate cancer. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 41, 100638 (2023).

Yock, A. D. et al. Anisotropic margin expansions in 6 anatomic directions for oropharyngeal image guided radiation therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 87, 596–601 (2013).

Verhoeven, K. et al. Boost delineation in breast radiation therapy: Isotropic versus anisotropic margin expansion. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 6, e243–e248 (2016).

Tang, C. et al. Feasibility and dosimetric evaluation of single- and multi-isocentre stereotactic body radiation therapy for multiple liver metastases. Front. Oncol. 13, 1144784 (2023).

Trager, M., Salama, J., Yin, F. F. & Adamson, J. SBRT treatment of multiple extracranial oligometastases using a single isocenter with distinct optimizations. J. Radiosurg. SBRT 4, 265–273 (2017).

Slagowski, J. M. & Wen, Z. Selection of single-isocenter for multiple-target stereotactic brain radiosurgery to minimize total margin volume. Phys. Med. Biol. 65, 185012 (2020).

Alaei, P., Gerbi, B. J. & Geise, R. A. Evaluation of a model-based treatment planning system for dose computations in the kilovoltage energy range. Med. Phys. 27, 2821–2826 (2000).

van Hoof, S. J., Granton, P. V. & Verhaegen, F. Development and validation of a treatment planning system for small animal radiotherapy: SmART-Plan. Radiother. Oncol. 109, 361–366 (2013).

Noblet, C. et al. A new tissue segmentation method to calculate 3D dose in small animal radiation therapy. Radiat. Oncol. 13, 32 (2018).

Olson, B., Li, Y., Lin, Y., Liu, E. T. & Patnaik, A. Mouse models for Cancer Immunotherapy research. Cancer Discov. 8, 1358–1365 (2018).

Yasmin-Karim, S. et al. Boosting the abscopal effect using immunogenic biomaterials with varying radiation therapy field sizes. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 112, 475–486 (2022).

Paddick, I. A simple scoring ratio to index the conformity of radiosurgical treatment plans. Technical. note. J. Neurosurg. 93(Suppl 3), 219–222 (2000).

Rodriguez-Berriguete, G. et al. Small-Molecule Polθ Inhibitors Provide Safe and Effective Tumor Radiosensitization in Preclinical Models. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, 1631–1642 (2023).

Kummer, B. et al. Value of functional in-vivo endpoints in preclinical radiation research. Radiother. Oncol. 158, 155–161 (2021).

McWilliam, A. et al. Radiation dose to heart base linked with poorer survival in lung cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer 85, 106–113 (2017).

Ghita, M. et al. Cardiac sub-volume targeting demonstrates regional radiosensitivity in the mouse heart. Radiother. Oncol. 152, 216–221 (2020).

Verhaegen, F. et al. Roadmap for precision preclinical x-ray radiation studies. Phys. Med. Biol. 68, 06RM01 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Murine data was collected with funding support from National Institutes of Health grants P41 EB002034, R01 CA098575, R50 CA211408 under IACUC protocol 71697. This work was supported by funding from the American Cancer Society IRG-19-136-59-IRG-02 grant via the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center. RT received funding for this and related work from the Biological Sciences Collegiate Division (BSCD) at the University of Chicago, College Center for Research Fellowships (CCRF) at the University of Chicago, and Department of Medical Physics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison from the following programs: BSCD Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship in Bioimaging for Oncology and Related Disciplines (SURFBOARD) for two summers, CCRF QUAD Summer Undergraduate Research Grant for a summer, CCRF QUAD Academic Year Undergraduate Research Grant for four academic quarters, and Academic Summer Student Undergraduate Research Enhancement (ASSURE) Program for a summer. GR received funding for related work from the American Cancer Society IRG-16–222-56 grant via the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center (National Institutes of Health: P30 CA14599).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RT, EP, AA, IA, and DOV worked on treatment and imaging data curation. RT, EP, AA, IA, and NS worked on treatment planning. RT, EP, BA, JMS, RN, and GR contributed to the conceptualization, study design, and interpretation of results. BA, EP, RN, BE, and HJH provided computational resources and software for the study. IG, BE, and HJH were responsible for the imaging of the animals and generating the original experimental treatment data in the retrospective study. EP and BA provided supervision for the entire study. RT performed the data analysis, drafted the original manuscript, and prepared Figs. 2–7. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

HJH and BE respectively hold US patent 8,664,955 (US-8664955-B1) and patent 9,392,957 (US-9392957-B1) for aspects of the pO2 imaging technology. Both individuals are also members of a start-up company O2M Technologies, LLC. The other authors declare no known commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest for this research. All authors state that they have no other competing interests to disclose, including non-financial interests.

Approval for animal experiments

The data used here was from a previous animal study approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. This previous study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation, institutional requirements, and ARRIVE guidelines. All methods from this previous study followed US Public Health Service policy and NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tummala, R., Pearson, E., Antes, A. et al. Retrospective analysis and IMRT replanning of a 3D-CRT murine dose painting study for preclinical oxygen-guided radiotherapy. Sci Rep 15, 17755 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01716-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01716-6