Abstract

Despite the need to follow ergonomic guidelines for efficient work, standard practices are lacking. The evolution of laparoscopic surgery has raised ergonomic issues further. This was a cross-sectional study using the online questionnaire survey by CHERRIES and STROBE guidelines among 64 laparoscopic practicing gynecological surgeons after the ethical approval. Continuous convenience sampling was used. The JASP 0.19 software was used, and descriptive analysis and relative risk were calculated. Among 64 surgeons who participated in the survey, 45 (70.31%) surgeons were aware of the ergonomics guidelines in laparoscopy, whereas 41 (64.06%) claimed to practice but 4 (6.25%) didn’t practice guidelines with the risk of not practicing 11.25 (95% CI 4.15–28.67). Total of 59 (92.19%) surgeons reported feeling musculoskeletal pain, where 46(71.88%) had pain in at least 2 body parts, commonly neck pain 44 (68.75%) followed by wrist pain 26 (40.63%). Among those surgeons feeling pain, 50 (78.13%) had not sought treatment and only 2(3.13%) took leave for rest. The risk of musculoskeletal pain when ergonomics was not practiced is 1.06 (95% CI 0.928–1.211). When the instrument didn’t fit well in the hand the risk of wrist pain was 1.25 (95% CI 0.447–3.494).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Physical ergonomics is the study of the body’s relation to its surrounding environment and the resultant consequences on the body due to posture, motion repetition, workplace design, material handling, and musculoskeletal strain1. Musculoskeletal pain (MSP) is a common occupational disease among the health personnel2,3,4,5,6. Due to the growing prevalence it has been termed as “an impending epidemic”6. Less adherence to ergonomics leads to MSP, especially in highly operative demanding surgeries like Laparoscopic surgeries (LS)7,8.

The evolving field of Minimally invasive surgeries (MIS) has greater benefits for patients having low complication rate, and shorter hospital stays but tends to increase the physical workload of the surgeons9,10. LS have restricted freedom of movement and surgeons compensate for this by adjusting with suboptimal positions and movements which increase the MSP1,11. The musculoskeletal disorders range from 73 to 88% in surgeons practicing MIS, with 24.7% having backache and 23% neck and shoulder pain9. The MSP prevalence in surgeons and interventionists was comparable to high-risk workers like laborers6. So there is a growing need for ergonomic intervention12. Though LS is a well- developed field, the low and middle-income countries (LMIC) are still unable to provide it readily13,14. The MSP indirectly affects the patient’s safety as the work accuracy and performance may be compromised subsequently shortening the surgeon career1,9,12. Also, there is underreporting of the MSP by the surgeons, and this needs to be addressed11,15.

So, exploring the discomfort faced by the surgeons and the ergonomics practice will help to address and create a pain-free, comfortable working environment for them. This study was carried out to find out the awareness, implementation, and effects of ergonomics on laparoscopy practicing gynecological surgeon in Nepal.

Methods

Study design and ethical considerations

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study with an online survey by the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES)16 and Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)17 guidelines. The research was conducted from August 1, 2023, to December 31, 2023, following ethical approval from the Nepal Health Research Council (Reference No: 298) dated 29 August 2023. The study was carried out according to the approved proposal and by the “Declaration of Helsinki”. The confidentiality of the participants was maintained throughout the study. The data were kept on MS Excel 2016 and were password protected. This study did not have risks to the participants.

Study population

This study was conducted among gynecological surgeons practicing laparoscopy in different parts of Nepal and who were registered members of the Nepal Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (NESOG). Contact information about practicing laparoscopic surgeons was taken from documentation of different conferences and programs held under the NESOG society on laparoscopy in Nepal in the past year. Contact information of a total of 100 of the participants was retrieved and they were contacted through email.

A Google form including all necessary information, informed consent, and the questionnaire was created and sent to all laparoscopy practicing registered gynecologists of NESOG society on their respective emails. The survey had two pages where the first, information about the study, the length of time for completion of the survey, data storage and protection policy, information about the investigators, and purpose of the study was attached, and once the participants consented to the study by opting “Yes I agree to participate” they were requested to proceed to the next page of the survey containing the questionnaires. In this way, informed consent was taken from all the participants which ensured the willful engagement in the study. To get a high response rate, the questionnaire utilized a combination of option buttons and checkboxes for single and multiple responses, respectively. At the end of the survey, the participants were asked to recheck the responses and correct any if needed before submitting it.

To prevent multiple entries, the email ID of the participant was also recorded and in case of duplication the recent response was taken and later ones were deleted. To ensure the completeness of the responses to all the questions, each question was marked “required” and if not filled would prompt them to fill it before submitting. Additionally, multiple follow-up requests during the study period were sent to non-respondents at two-week intervals via email. A maximum of four requests were sent to non-respondents, and failing to respond after this resulted in exclusion from the study.

Sampling method

Continuous convenience sampling was used.

Online survey

The survey consisted of comprehensive questions based on a review of the literature. The questionnaire was thoroughly pretested to confirm its validity and reliability. For the face and content validity, three experts and the pretest participants reviewed the questions and their relevance. For the pretest, ten respondents were randomly picked by applying the “=RAND( )” function in MS EXCEL and selecting the top ten entries from the generated list. They confirmed most of the question items were appropriate and the corrections were made according to the suggestions on some questions.

The questionnaire included the first section with questions regarding demographic profiles like age groups, gender, and height. The handedness was also inquired. There were questions about the years of experience and hours of practice of laparoscopy per week. The second section asked about the instruments, and adjustability of the monitor and operating table height. The fitting of different laparoscopic instruments like forceps, needle holders, or trochars in the hand was also asked.

With regards to MSP, the surgeons had to answer if they experienced pain during or just after the surgery within the last year, if yes how often and which body areas, and if formal medication or treatment was sought. We inquired about the perception of surgeons regarding their understanding of the ergonomic principles. They had to answer “yes” or “no” to “Are you aware of laparoscopic ergonomic guidelines?” and “Do you practice laparoscopic ergonomic guidelines during surgery?”.

Statistical analysis

The spreadsheet of the data was downloaded, and exported to MS Excel 2016 and was password protected and the access was restricted to authors. The statistical analysis was conducted using JASP 0.19 software. The main data did not include the pretesting results. The analysis primarily involved descriptive statistics to summarize the collected information. Chi- square test was used for categorical variables and relative risk was calculated. The p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The 95% confidence interval was calculated and reported.

Results

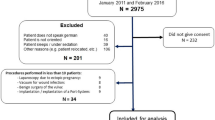

For this study, 100 registered laparoscopy practicing gynecologists who were members of the NESOG society practicing laparoscopic surgery were contacted via email. A total of 74 responded to the survey with a 74% response rate. A comprehensive pretest with 10 random respondents from the total sample was conducted to increase the questionnaire’s reliability. The results included intentional modifications to enhance the survey tool’s validity and overall quality. So, excluding 10 pretest samples we had a total of 64 (64%) respondents for analysis.

Among the 45 (70.32%) surgeons aware of the ergonomics guideline in laparoscopy, 41 (64.06%) claimed to practice guidelines but 4 (6.25%) didn’t practice. The risk of a surgeon not practicing the ergonomics guidelines when not aware of the guidelines was 11.25 (95% CI 4.15–28.67).

While 5 (7.81%) of the surgeons didn’t report any sort of musculoskeletal pain during or just after the surgery within last year of the survey, 59 (92.19%) reported feeling pain in the body area. Most of the surgeons 42 (71.88%) report feeling pain in at least 2 body parts. Among those surgeons feeling pain 9(15.25%) had to take medication for the pain and 2 (3.39%) surgeons had to take leave for more than a day due to pain within the last year. Still 50 (84.74%) of the surgeons having MSP did not seek formal treatment and continued to work despite the pain. The 44 (68.75%) surgeons reported having pain sometimes and 5 (7.81) felt MSP most of the time.

The most common area where pain was reported by the surgeon was the neck region in 44 (68.75%). Lower back pain in 15 (23.44%) surgeons (Fig. 1). Wrist pain was present in 26 (40.63%) of the surgeons. When the instrument didn’t fit well in the hand the risk of wrist pain was 1.25 (95% CI 0.447–3.494). Four (6.25%) surgeons were below 150 cm in height whereas 8 (12.50%)surgeons were above 170 cm.

Most of the surgeons were less than 50 years of age and laparoscopy practicing female gynecological surgeons were slightly more than male gynecologists (Table 1). At least up to 5 hours of laparoscopic surgery was done by most surgeons in a week. Laparoscopic radical hysterectomy could be performed by 7 (10.94%) surgeons and at least basic laparoscopic surgery like cystectomy could be performed by 10 (15.63%) surgeons.

Most of the surgeons still used single monitor, its height could not be adjusted in 38(59.38%) of cases and 58(90.62%) of surgeons used the monitors at or above eye level. The operating table height was not adjustable in 3(4.69%), while 49(76.56%) of surgeons preferred it to be at or above the waist level (Table 2).

Inferential analytics

When the practicing surgeon didn’t adhere to ergonomic principles there was an increased risk of back pain and wrist pain. Also, the overall reporting of the musculoskeletal pain increased (Table 3).

Back pain was not significantly related to the height of the surgeon or the presence of the adjustability of the operation table or the level of it (Table 4).

Neck pain was statistically significantly related to the practice of the guidelines but the level of the monitor used didn’t relate to it (Table 5).

Discussion

The use of MIS, like Laparoscopic surgeries (LS), is increasing in different parts of the world and the awareness of ergonomics is less in many surgeons practicing it11,18. Musculoskeletal pain (MSP) is increasing and is underreported by surgeons1,11,15. This study underlines the fact though many surgeons are aware of ergonomic principles, not all practice them. Most of these surgeons had MSP with at least two body parts involved.

LS is practiced commonly in developed countries but in LMIC it is still not readily available due to the high cost of equipment, the need for maintenance, the lack of trained manpower, and lack of wet and dry labs for training19. LS are advantageous to patients as there is a decrease in postoperative complications and hospital stay but have increased physical stress, injuries, and burnout in surgeons as they have to work in suboptimal positions due to reduced freedom of movement and higher physical demands1,8,12,20,21,22,23. To cope with these discomforts, surgeons have been limiting the number of cases10. In our study, many surgeons report having MSP but 50 (84.74%) of them still have not sought treatment for it and continued their work despite the pain. A similar kind of underreporting of MSP by the surgeons is reported in other studies11,24. A recent Meta-analysis shows a high prevalence of MSP among gynecological laparoscopy practicing surgeons having similar findings to our study, and 70% of them did not opt for treatment25. In an online survey conducted in the developed country among gynecological surgeons practicing MIS among 260 respondents 88% had physical discomfort but only 29% received treatment for the pain symptoms10. While surgeons in our study experienced greater physical discomforts than in this research, they were less likely to seek treatment, highlighting differences in treatment-seeking behavior among populations. A systematic review also reported a 74% prevalence rate of MSP among surgeons practicing MIS which is still lower than our study9. In the study by Esposito et al. laparoscopic surgeons suffered from MSP even at home disturbing their sleep and they believed it was due to LS’s bad ergonomics26. In a survey conducted among laparoscopic surgeons MSP was reported higher in long cases than in short cases27. In our study, we did not inquire about the pain and duration of the surgery. In another online survey of 300 surgeons practicing in Italy, 98.7% experienced pain, among which 46.2% had pain once a month and 62.7% correlated pain to LS28. In the assessment of the burden of MIS on surgeons a study reports physical discomforts in 61.8 − 75.3% of surgeons which is also less than our study probably because they adhere more to ergonomics and have better availability of standardized equipment than in LMIC29. Those surgeons also considered pain may cause their early retirement29. In a study of LS in LMIC the complication rate and hospital stay of patients were reduced but it fails to explore the impact it has on the surgeons19. So MSP may result from substandard practice not adhering to ergonomic principles and is a global occupational health challenge. In a recent study by Chan et al. conducted among surgery residents assisting in minimally invasive abdominal surgery the physical discomfort (pain, fatigue, numbness, or stiffness) and severe discomfort decreased after the ergonomic improvements from 82.6 to 81.3% and 37.0 to 34.4% respectively, but the changes were not statistically significant30. The small insignificant decrease in discomfort may be due to different preferences of surgeons in 3 different institutions involved in the study and also may be because of minimal modifications in the ergonomics practice. Hence, total adherence to ergonomic principles may help in decreasing the discomfort.

In our study, the awareness of ergonomics was present in 70.32% of the participants but still, 6.25% of them didn’t practice it may be due to a lack of training. In a study by Pizzol et al., the importance of training to the surgeons in LMIC is pointed out19. The cause of pain after MIS is mostly attributed to poor ergonomic adherence by the surgeon29. In an open questionnaire survey among MIS surgeons in Europe, 11% were unaware of the ergonomic guidelines but 100% of them asserted the importance of ergonomics31. In a survey of Spanish surgeons by Rodriguez et al. 96.9% of them believed the physical discomfort was due to improper postures during the surgery and 100% (n = 131) wanted improvement in their work environment32. This shows that even surgeons in developed countries are not satisfied with the working conditions. In another survey among LS surgeons 96% believed that ergonomics training should be incorporated into the training courses as lack of ergonomics practice affected performance27. The pre-symposium survey by Cerier et al. reported that 80% of the participants felt a lack of awareness of surgical ergonomics at their institutions33. Though this is slightly higher than our study it is still comparable showing the need for intervention and formal training or education regarding ergonomics.

Formal education and trainings are necessary and intraoperative breaks and stretching will also help in reducing MSP in gynecological MIS surgeons34. The importance of ergonomic training to gynecological surgeons practicing MIS has been outlined in other studies and the need is felt by the author of this study as well10,11,18,23.

Though more numbers of surgeons were aware of ergonomics guidelines in this study still, there was a lack of proper instruments for practicing it. The monitor should be placed at or 15 degrees below the eye level of the surgeon at a distance of 60 cm11,35. In our study, most of the monitors used were reported to be at or above the eye level and the height was not adjustable.

Though adhering to the ergonomic guidelines, poor design of the instrument still may cause MSP1. There is a report of LS instruments not tailored to surgeons of different heights and hand sizes35. In our study four surgeons 4(6.3%) are below 150 cm and the instruments also don’t fit their hand sizes which has increased the MSP in them. Smaller hand sizes decrease the grip strength and thereafter increase the ergonomic workload for the surgeons and this may have been the case in our study participants as well27,36,37.

Limitations of the study

The small sample may have limited the statistical power with wide confidence interval. There was no control group to compare and establish the causality limiting the generalizability of the results. A key limitation of this study is reliance on the self-reported understanding of the ergonomic guidelines by the surgeons rather than objective assessment of their knowledge. Since a validated ergonomics knowledge test was not used in this study the findings may have been influenced by self-reporting bias. Future studies with direct observations of the practice of ergonomics by surgeons or the use of standardized knowledge tests would validate the findings. This was self-reported data so the recall bias and response bias among the respondents could not be ruled out. The absence of pre-specified sample size calculation, due to the use of total participants in different programs under NESOG, could affect the statistical power and reduce sensitivity to detect smaller effect sizes. However, the full cohort inclusion minimizes the selection bias and enhances the real world applicability.

Strength of the study

This study focused on the underreported population which is gynecological surgeons of Nepal rather than most other studies which have focused on the practice of surgeons from developed countries. The operating room setup and training of surgeons may differ. So this study fills the region-specific data. We could quantify the risk of MSP if ergonomics is not practiced and also document the low treatment-seeking behavior of the gynecological surgeons of Nepal. We have been able to highlight the global ergonomics challenges that apply in low-resource settings. This study also points out the actionable gaps like provision of better instrument design and institutional support for pain management of the surgeons.

This study finding will help gynecological surgeons practicing LS have better insights about ergonomics and adhere to it. This would reduce the MSP increasing the career longevity of the surgeons and increase the day-to-day comfort. The operation time may decrease whereas patient outcomes may improve. This study has tried to quantify the relationship between MSP and the surgeon’s practice of LS. These data may help in the development and refinement of occupational health policies or guidelines in hospitals. Interventions for the pain management programs like onsite physiotherapy and counseling to reduce the stigma around reporting pain by practicing surgeons so that pain is managed earlier. Studies with larger sample size to further clarify the risks are needed. Longitudinal studies for exploring the relationship between pain and compliance with ergonomics will further substantiate the findings of the study. A study with a control group would also establish the causality. Future studies to find out the factors contributing to less implementation of ergonomic guidelines would identify the barriers and allow addressing them. The study of the improvement of the MSP before and after the ergonomic interventions may also guide in establishing the effectiveness of ergonomics in LS.

Conclusions

This study highlights the occupational hazard of musculoskeletal pain reported by laparoscopy practicing gynecological surgeons of Nepal, which is related to noncompliance with ergonomic principles and poor fit of instruments. Despite the pain reported by more than 90% of surgeons, more than two-thirds didn’t seek treatment for the pain and continued to work underscoring the critical neglect of occupational health. Though the risks were not statistically significant, intervention to prevent pain and protect surgeon health is warranted. These findings underscore the urgent need for ergonomic training, proper equipment availability, and policy level interventions to promote laparoscopic surgeons’ occupational health, prevent long term health complications, and ensure the longevity of their careers.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Zahiri, H. R., Addo, A. & Park, A. E. Musculoskeletal disorders in minimally invasive surgery. Adv. Surg. 53, 209–220 (2019).

Rambabu, T. & Suneetha, K. Prevalence of work related musculoskeletal disorders among physicians, surgeons and dentists: a comparative study. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 4, 578–582 (2014).

Fan, L. J. et al. Ergonomic risk factors and work-related musculoskeletal disorders in clinical physiotherapy. Front. Public. Health. 10, 1083609 (2022).

Dong, H., Zhang, Q., Liu, G., Shao, T. & Xu, Y. Prevalence and associated factors of musculoskeletal disorders among Chinese healthcare professionals working in tertiary hospitals: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 20, 175 (2019).

Mansoor, S. N., Arabia, A., Rathore, F. A. & D. H. & Ergonomics and musculoskeletal disorders among health care professionals: prevention is better than cure. JPMA J. Pak Med. Assoc. 72, 1243–1245 (2022).

Epstein, S. et al. Prevalence of Work-Related musculoskeletal disorders among surgeons and interventionalists. JAMA Surg. 153, e174947 (2018).

Armijo, P. R. et al. Gender equity in ergonomics: does muscle effort in laparoscopic surgery differ between men and women? Surg. Endosc. 36, 396–401 (2022).

Miller, K., Benden, M., Pickens, A., Shipp, E. & Zheng, Q. Ergonomics principles associated with laparoscopic surgeon injury/illness. Hum. Factors. 54, 1087–1092 (2012).

Alleblas, C. C. J. et al. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among surgeons performing minimally invasive surgery: A systematic review. Ann. Surg. 266, 905–920 (2017).

Franasiak, J. et al. Physical strain and urgent need for ergonomic training among gynecologic oncologists who perform minimally invasive surgery. Gynecol. Oncol. 126, 437–442 (2012).

Catanzarite, T., Tan-Kim, J. & Menefee, S. A. Ergonomics in gynecologic surgery. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 30, 432–440 (2018).

Yang, L. et al. Intraoperative musculoskeletal discomfort and risk for surgeons during open and laparoscopic surgery. Surg. Endosc. 35, 6335–6343 (2021).

Balogun, O. S. et al. Development and practice of laparoscopic surgery in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Niger J. Clin. Pract. 23, 1368 (2020).

Wilkinson, E., Aruparayil, N., Gnanaraj, J., Brown, J. & Jayne, D. Barriers to training in laparoscopic surgery in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Trop. Doct. 51, 408–414 (2021).

Wells, A. C., Kjellman, M., Harper, S. J., Forsman, M. & Hallbeck, M. S. Operating hurts: a study of EAES surgeons. Surg. Endosc. 33, 933–940 (2019).

Eysenbach, G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J. Med. Internet Res. 6, e34 (2004).

Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 13, S31–S34 (2019).

Tamburacı, E. & Mülayim, B. Awareness and practice of ergonomics by gynecological laparoscopists in Turkey. Ginekol. Pol. 91, 175–180 (2020).

Pizzol, D. et al. Laparoscopy in low-income countries: 10-year experience and systematic literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 5796 (2021).

Shugaba, A. et al. Should all minimal access surgery be Robot-Assisted? A systematic review into the musculoskeletal and cognitive demands of laparoscopic and Robot-Assisted laparoscopic surgery. J. Gastrointest. Surg. Off J. Soc. Surg. Aliment. Tract. 26, 1520–1530 (2022).

Mendes, V. et al. Experience implication in subjective surgical ergonomics comparison between laparoscopic and robot-assisted surgeries. J. Robot Surg. 14, 115–121 (2020).

Dalager, T., Søgaard, K., Bech, K. T., Mogensen, O. & Jensen, P. T. Musculoskeletal pain among surgeons performing minimally invasive surgery: a systematic review. Surg. Endosc. 31, 516–526 (2017).

Gillespie, A. M., Wang, C. & Movassaghi, M. Ergonomic considerations in urologic surgery. Curr. Urol. Rep. 24, 143–155 (2023).

Michael, S., Mintz, Y., Brodie, R. & Assalia, A. Minimally invasive surgery and the risk of work-related musculoskeletal disorders: results of a survey among Israeli surgeons and review of the literature. Work Read. Mass. 71, 779–785 (2022).

Wu, L. et al. Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain among gynecologic surgeons performing laparoscopic procedures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. Off Organ. Int. Fed. Gynaecol. Obstet. 161, 151–158 (2023).

Esposito, C. et al. Work-related upper limb musculoskeletal disorders in paediatric laparoscopic surgery. A multicenter survey. J. Pediatr. Surg. 48, 1750–1756 (2013).

Shepherd, J. M., Harilingam, M. R. & Hamade, A. Ergonomics in laparoscopic surgery—a survey of symptoms and contributing factors. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc Percutan Tech. 26, 72–77 (2016).

Restaino, S. et al. Ergonomics in the operating room and surgical training: a survey on the Italian scenario. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1417250 (2024).

Morton, J. & Stewart, G. D. The burden of performing minimal access surgery: ergonomics survey results from 462 surgeons across Germany, the UK and the USA. J. Robot Surg. 16, 1347–1354 (2022).

Chan, C. et al. Evaluating the surgical trainee ergonomic experience during minimally invasive abdominal surgery (ESTEEMA study). Sci. Rep. 14, 12502 (2024).

Wauben, L. S. G. L., Van Veelen, M. A., Gossot, D. & Goossens, R. H. M. Application of ergonomic guidelines during minimally invasive surgery: a questionnaire survey of 284 surgeons. Surg. Endosc Interv Tech. 20, 1268–1274 (2006).

Rodríguez, J. S., Méndez, J. A. J. & Haro, F. B. Analysis of ergonomic aspects in the surgery field: Surgeons’ appraisals. in Proceedings TEEM: Tenth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality (eds. García-Peñalvo, F. J. & García-Holgado, A.) 192–200 (Springer, 2023). (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-0942-1_19

Cerier, E. et al. Survey of surgical ergonomics interventions: how to move the needle in surgical ergonomics. Glob Surg. Educ. - J. Assoc. Surg. Educ. 2, 91 (2023).

Lin, E., Young, R., Shields, J., Smith, K. & Chao, L. Growing pains: strategies for improving ergonomics in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 35, 361–367 (2023).

Quinn, D. & Moohan, J. Optimal laparoscopic ergonomics in gynaecology. Obstet. Gynaecol. 17 (2015).

Wong, J. M. K. et al. Ergonomic assessment of surgeon characteristics and laparoscopic device strain in gynecologic surgery. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 29, 1357–1363 (2022).

Sanchez-Margallo, J. A. et al. Comparative study of the use of different sizes of an ergonomic instrument handle for laparoscopic surgery. Appl. Sci. 10, 1526 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G, S.P and P.R.P planned and conceptualized the study. All authors: worked to make the form, acquire data, write the manuscript, and revise it.S.P and A.G : created the tables and figures, data analytics. All the authors have reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Approval for the study was taken from Nepal Health Research Council (Reference No: 298) dated 29 August 2023. Informed consent was attached with the questionnaire as the first page and once the participants consented for the study by opting “yes” only then they could proceed to the next page of questionnaire ensuring the willful participation. This study was conducted in accordance with the “Declaration of Helsinki”.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghimire, A., Pokharel, S., Ghimire, S. et al. Practice of ergonomics in laparoscopic gynecological surgeries and its effects on surgeons in a low-middle income country. Sci Rep 15, 35246 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01865-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01865-8