Abstract

The evolution of seepage field in large loess-mudstone landslides is significantly influenced by rainfall infiltration, which is a critical factor affecting their stability. This paper presented a case study of the Hongya Village landslide in Huzhu County, Qinghai Province, to better understand the impact of rainfall infiltration on the triggering mechanism of loess-mudstone landslides. A combination of field investigations, high-density electrical resistivity surveys, and numerical simulations was employed to systematically analyze the temporal and spatial distribution of pore water pressure, volumetric water content, and shear strain within the landslide mass under rainfall infiltration conditions. The results indicated that the rainfall infiltration markedly alters the seepage characteristics of the landslide mass, leading to a sharp increase in pore water pressure and a significant reduction in shear strength, which consequently reduced the overall stability of the landslide. The stability analysis identified a stepwise instability process in the landslide, characterized by “shear displacement-tensile failure-pulling effect” triggered by rainfall infiltration. The findings provide a comprehensive understanding of the instability mechanisms of loess-mudstone landslides under rainfall conditions, thereby offering valuable scientific guidance and technical support for the prevention and mitigation of similar landslide hazards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

China experiences frequent landslide hazards, particularly large and mega-landslides prevalent in the western regions. Large landslides are characterized by their significant scale, complex mechanisms, and significant hazards, which makes them globally representative phenomena1. With population growth and the expansion of human engineering activities, the incidence of geological hazards, including landslides, continues to rise2,3. In Qinghai Province, landslides represent one of the most common forms of slope failure. Previous studies have identified rainfall as a crucial direct factor in triggering landslides. Rainfall-induced landslides have become a focus of hazard prevention and control. Over 90% of loess landslides are related to rainfall, and there is a significant positive correlation between the frequency of landslides and rainfall, particularly in loess areas such as Shaanxi and Gansu, where joints are commonly developed and rainfall-triggered landslides are frequent4,5,6,7.

The instability mechanism of loess-mudstone landslides under rainfall infiltration conditions is primarily driven by the interactions between hydrological processes and the mechanical properties of the slope8,9. During periods of intense rainfall, water infiltration induces significant changes within the landslide body, ultimately leading to instability through two main pathways: Rainfall infiltration causes progressive saturation of the soil near the interface between loess and mudstone, transitioning it from an unsaturated to a saturated state10,11. This saturation process creates a thickened zone of saturated soil, which increases the self-weight of the slope material12. The added weight, combined with a reduction in shear resistance along the slip surface, significantly weakens the stability of the slope13. In addition to increasing the slope’s weight, infiltration also reduces the mechanical strength of the slip zone soil14,15.The infiltration process generates pore water pressure, which decreases the effective stress within the slope and further undermines its stability9,16,17,18. As these destabilizing effects accumulate, the slope becomes increasingly susceptible to failure, often culminating in large-scale sliding10.

Loess-mudstone landslides induced by rainfall are characterized by their complex instability mechanisms, which pose significant challenges for stability assessment and disaster prediction11,12,19,20. The dynamic interplay between infiltration, pore pressure development, and mechanical weakening creates a highly nonlinear and unpredictable system21. This complexity makes it difficult to establish reliable early warning systems. Consequently, in-depth research into the mechanisms of rainfall-induced instability in loess-mudstone landslides is of paramount importance13,22. Such studies not only provide critical insights into slope behavior under extreme environmental conditions but also hold practical value for improving disaster mitigation strategies and reducing risks associated with these hazardous geological phenomena23.

The literature review reveals that most of the existing studies on loess-mudstone landslides focus on qualitative analysis of rainfall infiltration, landslide deformation stages, and macro-prediction of landslide distribution and slope stability after rainfall. However, little research has been conducted on how changes in moisture content resulting from rainfall infiltration within the loess-mudstone landslide mass affect the groundwater seepage system and overall slope stability. Therefore, this study utilized the Hongya Village landslide in Huzhu County, Qinghai Province, triggered by rainfall, as a research prototype. Based on a comprehensive analysis of the regional hydrogeological conditions, the developmental characteristics of the prototype landslide, and the factors influencing slope stability, numerical simulations were performed to thoroughly investigate the responses and spatial-temporal distribution characteristics of matrix suction, volumetric water content, pore water pressure, slope displacement, and the stability factor of the sliding surface under rainfall conditions. Additionally, the evolution processes of water infiltration and slope instability were analyzed, and the crucial role of rainfall in triggering deep-seated loess landslides was elucidated. Finally, the numerical simulation for this type of landslide was optimized and improved in terms of model construction, boundary conditions, and simulation settings, aiming to provide theoretical insights and practical guidance for understanding the intrinsic causes of rainfall-induced deep loess landslides and for enhancing disaster prevention and mitigation strategies.

Overview of the study area

Geographical setting

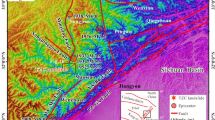

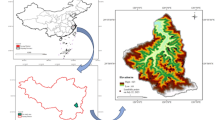

The Hongya Village landslide is a representative large-scale shattered bedding landslide located in Huzhu County, Haidong City, Qinghai Province, in western China. It is situated at the junction of the Loess Plateau and the Tibetan Plateau. The terrain is characterized by higher elevations in the north and lower elevations in the south, with the Daban Mountain extending from the northwest to the southeast throughout the region, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Most towns and villages in Huzhu County are situated in hilly and river valley areas, which are typical of hilly and river valley-type regions. The Hongya Village landslide is located at the transition zone between the low mountain hilly area on the right bank of the Nanmen Gorge River and the river valley plain area. The geographic coordinates of the center of the landslide are 101°56′13″E and 36°51′41″N. The river valley plain area features I and II-level terraces, which are distributed in strips. The terrain is relatively flat and open, and it is relatively stable. The low mountain hilly area has an elevation ranging from 2560 to 2840 m, with significant erosion and weathering effects. The mountain tops are smooth and rounded, with a cutting depth of 150 to 200 m, and the slopes typically range between 30° and 60°. The valleys are V-shaped or U-shaped, and the terrain is fragmented due to long-term erosion, forming ridge-like hillocks.

Geographical location of the Hongya Village landslide. The satellite imagery data were obtained from the publicly available platform GSCloud (https://www.gscloud.cn/). The map was generated and post-processed using ArcMap 10.8 (https://desktop.arcgis.com/).

Basic characteristics of Hongya village landslide

Slope Structure: The landslide area primarily consists of a sloped landform with a total height difference of approximately 150 m. The average slope is about 20°, although it may locally reach 50° to 60° at the rear and front edges. The steep terrain and significant elevation differences provide favorable conditions for the formation of the landslide. The slope surface is characterized by many water-sinkholes, which heighten the potential for local collapses or sliding to escalate into a full-scale landslide under prolonged rainfall and snowmelt infiltration. The front of the landslide is relatively flat, providing an unobstructed area for landslide movement. The overall slope direction of the landslide ranges from 120° to 170°, while the underlying mudstone layers dip at 130°∠12° to 15°, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The entire slope aligns with the bedding direction, which provides favorable geological conditions for the landslide occurrence. The landslide mass measures approximately 370 to 740 m in length, 470 to 1050 m in width, and covers an area of about 53.2 × 10⁴ m². Its average thickness is about 40 m, with an estimated volume of approximately 2108 × 10⁴ m³.

Material Composition: The upper part of the region is mainly composed of single-structured loess (Q3eol) and dual-layer structured silty soil and gravelly soil (Q4al + pl), while the lower part mainly consists of the Neogene Guizhi Formation (N2g) and Xining Formation (N1x) mudstone, as illustrated in Fig. 3. The loess exhibits a loose overall structure, characterized by large porosity and low strength. Vertical joints and fractures are well developed, and their shear and compressive strength are low, making them water-sensitive. The loess is overlaid by Neogene mudstone, which has poor diagenesis, and the rock mass is fragmented. Both strata possess low strength and high sensitivity to changes in moisture content. Upon exposure to water, they easily soften and form weak sliding surfaces, thereby becoming prone to sliding layers. The Guizhi Formation mudstone, which is mainly distributed at the rear of the Hongya Village landslide, displays a deposition pattern with a higher sandstone content in the lower part. Conversely, the Xining Formation mudstone is predominantly found in the middle and front sections, as well as in the terrace areas of the Hongya Village landslide, forming the sliding bed and terrace foundation, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Hydrogeological conditions

Groundwater characteristics in the landslide area

Field surveys and analyses of high-density electrical resistivity data indicated that the groundwater types in the landslide area mainly include perched groundwater in the loess and underlying gravel layer, as well as fracture water in the mudstone. The results of geophysical interpretation are elucidated in Fig. 5.

Perched water in the loess and underlying gravel layer: The loess and underlying gravel layer serve as the primary storage layers for shallow groundwater in the landslide area. The abundance of water is significantly influenced by topography, landforms, and recharge conditions. In regions characterized by relatively flat terrain and minimal erosion, the continuity of perched groundwater is strong. Conversely, in regions with pronounced valley cutting and fragmented terrain, the perched groundwater is subject to erosion, resulting in intermittent distribution. Geophysical survey profiles revealed that the loess and gravel layers exhibit relatively low resistivity, indicating good water content. However, in specific regions at the front and rear of the landslide, where the interface between the gravel layer and underlying mudstone is elevated, the perched groundwater may be either impeded or discharged.

Fracture water in mudstone: The fracture water in the bedrock of the landslide area is mainly located in the fractures of the Xining Formation (N1x) and Guizhi Formation (N2g) mudstones. Geophysical results revealed that regions with well-developed mudstone fractures demonstrate low resistivity, which correlates strongly with a water-saturated state. The weathering crust of the Xining Formation mudstone is relatively thick, with extensive fractures and high permeability, thereby providing sufficient space for the storage of fracture water. Long-term accumulation of water in sinkholes at the rear of the landslide has replenished the fracture water in the mudstone, forming a hydraulic enrichment zone at this location. The distribution of fracture water in the middle and front parts of the mudstone is controlled by the slope’s fracture system.

Recharge, runoff, and drainage conditions of groundwater

Recharge conditions: Groundwater in the landslide area is predominantly replenished through atmospheric precipitation infiltration. Geophysical data revealed the distribution range of the perched groundwater layer and the locations where fracture water is developed, which is consistent with the model indicating that groundwater is mainly recharged in the higher elevation areas of the slope. Water accumulated in sinkholes provides continuous recharge to the fracture water within the landslide mass through infiltration.

Runoff conditions: Geophysical findings demonstrate that groundwater in the landslide mass mainly flows horizontally. The runoff channels are concentrated within the loess gravel layer and mudstone fracture system. The movement pathways of the perched groundwater in the loess and gravel layers are short and controlled by the topography. The fracture water in mudstone has longer runoff pathways and flow along the fracture system toward the middle and lower parts of the landslide and the low-lying areas of the valley.

Drainage conditions: Both the model and geophysical results suggest that the perched groundwater locally emerges in the valley areas at the front of the landslide, forming springs or drains along fracture channels. The recharge of fracture water at the rear of the landslide is significant, and it mainly spreads laterally toward the middle part of the landslide mass.

Water-blocking conditions

There is a strong water-blocking effect in the landslide area, which can be attributed to two principal factors:

Xining Formation Mudstone Layer: Geophysical results show that the resistivity of the mudstone layer exhibits a narrow variation range, suggesting a high clay content and low permeability. which contribute to its significant water-blocking properties. This characteristic hinders the vertical infiltration of perched and fracture water, thereby enhancing the horizontal permeability of the landslide mass.

Shear Zone Soil Layer: Due to long-term shear deformation, the soil particles in the shear zone of the landslide have become finer, resulting in decreased porosity. A distinctive water-blocking layer is formed at both the top and bottom of the shear zone. Geophysical data reveals that the resistivity of the shear zone soil is low but demonstrates a homogeneous distribution, which is consistent with the water-blocking effect of the landslide mass.

Variation in pore water pressure and development of seepage model

Variation in pore water pressure in slope body under rainfall infiltration

The changes in pore water pressure and pore air pressure during seepage in unsaturated soils are governed by a complex dynamic water-air-solid equilibrium process24. These changes are constrained by the water-air-solid boundary interface, which functions as a contraction membrane. Seepage and deformation are interdependent physical phenomena, necessitating the incorporation of volumetric deformation and constitutive modeling in their analyses25. The incremental form of the volumetric deformation continuity condition for unsaturated soils can be simplified as:

where \(\:d{V}_{V}\:\)and \(\:{V}_{0}\:\)are the volume change and the initial volume of the soil body, respectively; \(\:d{V}_{w}\) represents the volume change of pore water, and \(\:d{V}_{a}\) represents the volume change of pore air. The volume change caused by air compression can be expressed as:

where \(\:S\) is the degree of saturation of the soil, \(\:n\) is the porosity of the soil, and \(\:{u}_{a}\) is the pore air pressure. When water flows through the soil, it may cause changes in the soil particle structure. If these structural changes are disregarded, the change in water content of the soil element can be calculated using the difference between the inflow and outflow rates, \(\:{q}_{in}-{q}_{out}\). The change in water volume can be expressed as:

where \(\:{q}_{in}\) and \(\:{q}_{out}\) represent the inflow and outflow rates of water in the soil element, respectively. \(\:\theta\:\) denotes the volumetric water content of the soil, and t represents the seepage time. Fredlund et al. proposed that when unsaturated soil is treated as an isotropic linear elastic material, the incremental form of the constitutive equation for unsaturated soil can be expressed as:

where E and H are the elastic moduli associated with the net normal stress, and µ is the Poisson’s ratio. The volumetric strain increment \(\:d{\epsilon\:}_{V}\) can be expressed as follows:

Considering the slope analyzed in this study as a plane strain problem, the deformation of the soil in the y-direction can be neglected. Setting \(\:d{\epsilon\:}_{y}\)=0 and substituting into Eq. (5), we obtain:

Substituting Eqs. (4), (6), and (8) into Eq. (7) yields:

where \(\sigma _{{ave}} = \left( {\sigma _{x} + \sigma _{z} } \right)/2\) is the average stress. For unsaturated soils, the volumetric strain equation under the plane strain compression condition is expressed as:

where \(m_{1}^{s} = 2\left( {1 + u} \right)\left( {1 - 2u} \right)/E\) and \(m_{2}^{s} = 2\left( {1 + u} \right)/H\) are the volumetric change coefficients related to net normal stress. The variation of the volumetric strain of the soil element can be expressed as:

Substituting Eqs. (2) and (3) into Eq. (11), we obtain:

From Eqs. (10) and (12), we derive:

Assuming that water is incompressible, the volumetric change of the liquid phase can be represented by the net flow rate. The constitutive relationship of the liquid phase can be derived from a semi-empirical formula, and its incremental form under plane strain conditions can be expressed as:

Under plane strain conditions, the compressive form of the constitutive equation for the liquid phase is expressed as:

where \(\sigma _{{ave}} = \left( {\sigma _{x} + \sigma _{z} } \right)/2\), \(m_{1}^{\omega } = 2\left( {1 + u} \right)/E\), and\(~m_{2}^{\omega } = 1/H\omega - \left( {E/H} \right)/E\omega\) are the volumetric change coefficients related to net normal stress. From Eqs. (3) and (15), we obtain:

Rearranging Eqs. (13) and (16) yields:

The above two equations can be simplified as:

Solving Eq. (19), we obtain:

where \(R_{1} = \frac{{m_{2}^{s} }}{{m_{2}^{s} - m_{1}^{s} - \left( {1 - S} \right)n/\bar{u}_{a} }}\);\(\:{R}_{3}=\frac{{m}_{2}^{\omega\:}-{m}_{1}^{s}}{{m}_{2}^{\omega\:}}\);\(R_{2} = \frac{{m_{1}^{s} }}{{m_{2}^{s} - m_{1}^{s} - \left( {1 - S} \right)n/\bar{u}_{a} }}\);\(\:{R}_{4}=\frac{{m}_{1}^{\omega\:}}{{m}_{2}^{\omega\:}}\);\(m_{1}^{s} = 2\left( {1 + \mu } \right)\left( {1 - 2\mu } \right)/E\);\(m_{2}^{s} = 2\left( {1 + \mu } \right)/H\);\(m_{1}^{\omega } = 2\left( {1 + \mu } \right)/E_{\omega }\);\(m_{2}^{\omega } = 1/H_{\omega } - \left( {E/H} \right)/E_{\omega }\). This study derived the pore water pressure formula under rainfall infiltration conditions, where the volumetric changes of the shrinkage membrane and the soil particles were neglected. This formula is based on the continuity condition of volumetric deformation of unsaturated soil, the isotropic linear elastic constitutive equation of unsaturated soil, and the constitutive relationship of the liquid phase. Subsequently, calculations of the pore water pressure under rainfall infiltration were performed using Eq. (20), and the results were compared with numerical simulations to verify the accuracy of the derived equation.

Establishment of seepage model

To address the issues associated with steady-state saturated seepage and the dynamic changes in transient unsaturated seepage over time, this study firstly employed seepage analysis software to for numerical simulations of the seepage process. The pore water pressure in the soil under various rainfall conditions were obtained and then utilized in the stability analysis. Subsequently, stability analysis software was used to assess the displacement conditions and stress-strain states of the landslide in different directions, and the stability under different pore water pressure states was evaluated based on the theory of limit equilibrium.

The H1-H1’ profile from the Hongya Village landslide was selected for the establishment of the numerical model, which was moderately simplified geometrically. Within the slope model, five monitoring points were established at 100-meter intervals, starting 10 m from the slope face, to monitor the changes in pore water pressure and volumetric water content over time throughout the entire landslide process, as depicted in Fig. 6. The advantage of this model lies in its geometric dimensions, which are identical to those of the prototype. It can effectively simulate the loess and mudstone layers, with soil physical and mechanical parameters consistent with the prototype landslide. Hydrogeological models, boundary conditions, mathematical models, rainfall intensity, permeability coefficients, and soil-water characteristics were meticulously defined. Adjustments to the model, parameters, or boundary conditions, along with iterative simulations, ensure the rationality and reliability of the numerical results.

Parameter setting

The prototype landslide H1-H1’ profile at Hongya Village was utilized for model setup. The soil layers are distributed from top to bottom as follows: loess, silt, pebble-cobble, and mudstone. Specifically, the upper 50 m of the model consist of loess, the lower 155 m comprise mudstone, and a 3-meter thick layer of ice-water deposited pebble-cobble is positioned between the loess and mudstone. The groundwater table was set at a depth of 20 m. On the right side of the model, there is a double-layer structure of silt and pebble-cobble soil, with the upper silt layer being 15 m thick and the lower pebble-cobble layer being 20 m thick. In the seepage analysis software, a saturated-unsaturated material model was selected for seepage analysis. The soil-water characteristic curve is defined using model parameters such as van Genuchten and Fredlund-Xing. The soil-water characteristic curve for loess used in the seepage analysis was regressed using the VG model26. Based on the obtained volumetric water content and matrix suction experimental data, the permeability function was derived from the saturated permeability coefficient, and a complete permeability function curve was obtained based on the soil-water characteristic curve. Different permeability coefficients for different strata and matrix suction conditions were used for numerical calculations. Table 1 presents the seepage analysis calculation parameters. Fredlund and Morgenstern proposed a framework that utilizes two independent stress state variables (σ-µa) and (µa-µw) to describe the stress state of unsaturated soil. They noted that the changes in volumetric water content θw are influenced by both the normal stress (σ-µa) and (µa-µw)27, represented by the equation:

where (σ-µa) is the net effective stress, µa is the pore air pressure, µw is the pore water pressure, \(\:{m}_{1}^{w}\) is the volumetric change coefficient of water related to the change in net effective stress, and \(\:{m}_{2}^{w}\) is the volumetric change coefficient of water related to the change in matric suction. Assuming that the coefficients \(\:{m}_{1}^{w}\) and \(\:{m}_{2}^{w}\) are constant within a specific time step, we have:

During seepage analysis, it is customary to assume that the total stress remains invariant over time, and that the pore air pressure equates to atmospheric pressure, thus:

Substituting Eq. (23) and \(h_{w} = y + u_{w} /\rho _{w} g\) (where the partial derivative of the hydraulic head with respect to time is zero) into Eq. (22), we obtain:

where, \(\:{\text{m}}_{2}^{\text{w}}\) represents the absolute value of the slope of the soil-water characteristic curve. When the soil is saturated, the soil-water characteristic curve is generally flat, resulting in \(\:{m}_{2}^{w}\) in Eq. (24) being approximately zero. Based on the above analysis, the governing equation for saturated-unsaturated seepage is:

During seepage analysis of landslides subjected to rainfall, the rise and fall of groundwater cause the landslide soil and rock mass to be in a saturated-unsaturated state. By incorporating saturated-unsaturated seepage into the calculations, the selection of boundary conditions can disregard the wetting front, thereby eliminating the need to modify nodes and elements. Concurrently, this approach yields results that are more aligned with actual field conditions28.

The physical and mechanical parameters of the modelled soil strata were set to be consistent with those of the prototype landslide. The mass in the unsaturated zone is computed using the soil’s volumetric water content function. The coupling of effective stress parameters and pore water pressure variation, as well as the Mohr-Coulomb model, was adopted for stress-deformation analysis, with specific parameters seen in Table 2. In this simulation, the soil-water characteristic curve was used to define the influence of matrix Suction on the shear strength. The lateral sides of the model were set as the boundaries of the sliding surface, and the stability factor of the landslide during rainfall infiltration was analyzed using the limit equilibrium method.

Model scenario setup

According to meteorological data, the Hongya Village landslide experienced six intense rainfall events in August 2022, accumulating a total of 224.7 mm of rainfall over 22 days. Notably, the maximum 24-hour rainfall recorded occurred on August 3, with a total of 49.4 mm. In the six days preceding the landslide (from August 26 to 31), the cumulative rainfall reached 55.7 mm. The combination of continuous rainfall and short-term heavy rainfall ultimately triggered the overall translational deformation of the Hongya Village landslide. To better reflect actual conditions in the time-history analysis, the rainfall process from August 3 (i.e., the first day of rainfall) to August 31 was simulated. The daily rainfall values (mm) were converted to unit discharge (m³/d/m²), and the flow boundary in the simulation was set to the unit discharge corresponding to the actual daily rainfall. Dynamic data throughout the simulation process were progressively obtained based on the daily rainfall amounts, as illustrated in Fig. 7.

Results analysis and discussion

Pore water pressure

The variation in pore water pressure within the model slope from its initial state through six rainfall events until the occurrence of the landslide is illustrated in Fig. 8. On August 3, the pore water pressure at the upper monitoring point 1 of the slope was − 194.41 kPa, while at the middle-lower monitoring point 5, it was − 119.25 kPa. The majority of the upper region of the landslide mass was subjected to pore water pressures, indicating the presence of matric suction in the upper region of the landslide mass. Matric suction, a form of negative pore water pressure, suggests that the soil contains less water, while the dry soil layers possess a greater suction, thereby providing stability against sliding. By August 15, the pore water pressure within the landslide gradually increased. It reached − 35.34 kPa at the upper monitoring point 1 and − 3.22 kPa at the middle-lower monitoring point 5, gradually approaching zero from negative values. This indicated that rainfall water began to infiltrate into the interior of the landslide, leading to a reduction in matric suction in these areas. The decrease in matric suction implied a decrease in the soil’s shear strength, making the soil within the landslide mass more prone to displacement. Nonetheless, the upper region still maintained a certain level of matric suction, thereby providing a degree of stability. On August 31, the pore water pressure at the monitoring point 1 rose to 112.76 kPa, while at the monitoring point 5, it rose to 156.86 kPa. There was a significant increase in pore water pressure in the lower part of the landslide, and the negative pore water pressure (matric suction) in the upper region noticeably decreased. These changes indicated a substantial increase in soil saturation and a trend towards complete saturation. The disappearance of matric suction and the rise in pore water pressure affected the stability of the upper, middle, and lower parts of the landslide, particularly the lower region, where the further increase in pore water pressure led to an increased risk of potential instability. The notable transition from negative to high positive pore water pressure values in the lower region indicated that the soil is saturated or supersaturated, demonstrating that the lower part of the landslide is most significantly affected by water. The accumulation of water and the continuous rise in pore water pressure suggested that the lower region may develop a sliding plane to become the most unstable part of the landslide, which is highly prone to instability and sliding.

Figure 6a,b,c display the distribution of pore water pressure during different rainfall periods. It was observed that rainwater first infiltrates the soil vertically, then percolates downward along the slope, and finally reaches the toe of the slope. Under intermittent rainfall conditions, the loess-mudstone landslide underwent multiple cycles of rainfall and intervals. During rainfall periods, infiltration led to surface runoff that erodes the slope. During intervals, evaporation led to the development and expansion of cracks. Under continuous rainfall conditions, the erosive effect of surface flow became more pronounced, thereby leading to the formation of numerous erosion gullies on the slope surface, with soil particles mixed with rainwater being washed out of the model box. This process caused the slope body to creep and crack, ultimately leading to slope instability. The impact of rainfall infiltration on the stability of loess-mudstone slopes was mainly manifested in three aspects: ① Infiltration reduced the matric suction of the unsaturated soil above the groundwater table, thereby decreasing soil shear strength and weakening slope stability. ② Downslope seepage increased the sliding force of the slope body. ③ In the presence of seepage, fine particles migrated within the pores and were washed out of the slope body, known as seepage erosion, which resulted in collapse along erosion channels and caused instability and failure of the slope body.

To validate Eq. (20) for changes in pore water pressure during the seepage process, calculated pore water pressure values at monitoring points 1–5 under identical rainfall infiltration conditions were compared with numerical simulation results. The relative error between calculated and simulated values was determined using the formula: \(\:\text{R}\text{e}\text{l}\text{a}\text{t}\text{i}\text{v}\text{e}\:\text{e}\text{r}\text{r}\text{o}\text{r}\:=\frac{\text{C}\text{a}\text{l}\text{c}\text{u}\text{l}\text{a}\text{t}\text{e}\text{d}\:\text{r}\text{e}\text{s}\text{u}\text{l}\text{t}\text{s}-\text{S}\text{i}\text{m}\text{u}\text{l}\text{a}\text{t}\text{e}\text{d}\:\text{r}\text{e}\text{s}\text{u}\text{l}\text{t}\text{s}}{\text{S}\text{i}\text{m}\text{u}\text{l}\text{a}\text{t}\text{e}\text{d}\:\text{r}\text{e}\text{s}\text{u}\text{l}\text{t}\text{s}}\times\:100\%\). The calculated values, numerical results, and corresponding relative errors are summarized in Table 3.

For the loess-mudstone slope, the pore water pressure values at monitoring points 1–5, calculated using Eq. (20), exhibited a maximum error of 7.50% compared to the numerical simulation results. This close correspondence indicated a good agreement between the two sets of results, thereby validating the accuracy and rationality of Eq. (20).

Volumetric water content

The distribution of volumetric water content in the model slope under different rainfall conditions at various times and the time-dependent curves of volumetric water content at different monitoring points are illustrated in Fig. 9. At the initial stage of the simulation, the volumetric water content of the soil below the groundwater table and above the mudstone in the landslide mass was generally higher than 0.41, particularly in the middle and lower parts of the double-layer structure of silt and pebble-cobble soil, where the volumetric water content exceeded 0.5 and gradually decreased from the center outward. In the upper part of the slope, the volumetric water content in the loess area ranged between 0.28 and 0.31, while in the area below the ice-water deposited pebble-cobble layer and above the groundwater table, the volumetric water content was between 0.05 and 0.12, as depicted in Fig. 7a. By August 15, following a cumulative rainfall of 145 mm, the surface soil particles began to transition from an unsaturated to a saturated state, with a thickness of approximately 0.8 m. The volumetric water content at the slope surface rose to 0.43, and the volumetric water content in the middle soil layer of the slope increased to 0.35. This rainfall infiltration gradually reached the groundwater and formed a continuous surface, which indicated that continuous rainfall or groundwater recharge facilitate the penetration of water into the middle region of the landslide mass. The continuous accumulation of water gradually increased the weight and pore water pressure of the soil in the landslide mass, thereby reducing the shear strength. According to the time-dependent curves of volumetric water content in Fig. 7d, the daily rainfall amount recorded from August 18 to 19 was less than 5 mm, resulting in a significant decrease in the growth trend of volumetric water content at monitoring points. As illustrated in Fig. 7c, by August 31, some parts below the groundwater table in the middle of the slope exhibited an increase in volumetric water content, indicating that rainfall water had essentially penetrated into various deeper layers of the landslide mass. This further elevated the groundwater table, with volumetric water content near the sliding surface approaching saturation. This distribution characteristic of high volumetric water content led to a further reduction in the shear strength of the landslide mass. At the same time, the softening effect of water made the soil in the landslide mass tend to become unstable, significantly increasing the risk of overall sliding of the landslide mass.

Maximum shear strain

Following the SEEP/W analysis, the distribution of pore water pressure was used as input for the SIGMA/W module to conduct an analysis of the maximum shear strain in the model slope. The resulting nephogram of maximum shear strain is presented in Fig. 10. Observations revealed that the distribution of maximum shear strain highlights strain accumulation characteristics at the front, middle, and rear edges of the landslide mass. This indicated that the overall movement of the landslide mass is primarily driven by a pushing effect at the bottom and a pulling effect at the top, categorizing it as a push-pull type landslide. Under conditions of rising groundwater levels induced by rainfall, the front edge of the landslide (i.e., the red and orange areas near the toe of the slope in the figure) was the first region to experience the effects of increased pore water pressure, resulting in significant concentration of shear strain. This concentration reflected the loss of stability of the soil at the front edge of the landslide due to the rise in water levels. The driving force first formed at the leading edge and then propagated upwards, thereby causing tensile and pulling effects in the middle and rear parts of the landslide mass.

-

(1)

The front edge area of the landslide (pushing effect area) was influenced by rainfall infiltration, which caused the groundwater level to rise at the contact zone between the loess and mudstone near the toe of the slope. As the front edge of the landslide was positioned at the lowest point at the toe, it was directly affected by water infiltration, leading to an increase in pore water pressure and a significant reduction in shear strength. The maximum shear strain at the front edge of the landslide was concentrated at the boundary between the loess and mudstone layers, with a significant distribution of red and orange shear strains. This area exhibited the strongest sliding effect and served as the initial region for the landslide’s movement. The pushing effect at the front edge of the landslide displayed a “wedge” characteristic, wherein the front edge gradually slid downward due to water pressure and compressed the soil at the bottom, thereby driving the downward movement of the entire landslide mass. This pushing effect was transmitted to the middle and rear parts of the landslide, providing the initial momentum for the upper part to slide.

-

(2)

The middle area of the landslide (tensile-push transition zone) served as a transition zone between the pushing effect at the front and the pulling effect at the rear. As the pushing effect from the front edge was transmitted to the middle part, the shear strain in this area also gradually increased. However, due to its central position within the landslide mass, this area experienced both pushing and tensile forces simultaneously. The distribution of maximum shear strain revealed that this area is mainly green and yellow, indicating significant deformation; however, it did not reach the high strain levels observed at the front edge of the landslide. In the push-tensile transition zone, the soil was subjected to both the compressive force from the pushing at the front edge and the tensile force from the pulling at the rear edge. Consequently, the soil deformation in the middle part was characterized by an “arch-like structure,” resulting in a slight curvature due to the combined action of pushing from above and pulling from below, as well as stress accumulation near the loess-mudstone interface.

-

(3)

The rear edge area of the landslide (pulling effect area) was primarily influenced by the pulling effect. The pushing effect transmitted from the front edge and the middle part of the landslide generated a tendency for sliding at the rear edge under the influence of gravity. The distribution of maximum shear strain indicated that the shear strain in the rear edge was primarily concentrated in the middle and upper parts of the loess layer near the ground surface, indicating that the soil in this area was subjected to tensile deformation due to the pulling effect resulting from the pushing at the front edge. The tensile deformation at the rear edge of the landslide led to the progressive expansion of cracks and shear zones, increased surface tension, and the formation of a certain “tensile fracture” characteristic. This tensile fracture phenomenon further reduced the overall constraint of the soil at the rear edge, resulting in a downward sliding trend during the push-pull process. The pulling sliding at the rear edge not only arose from the pushing effect at the front edge but was also directly affected by rainfall infiltration and the rise in groundwater levels. The accumulation of the pulling effect at the rear edge reduced the overall stability of the rear part of the landslide mass, which could eventually lead to the instability and collapse, thereby exacerbating the overall sliding of the landslide mass.

Landslide stability analysis

The pore water pressure distribution obtained from the SEEP/W analysis was continuously used as input for the SLOPE/W module to conduct landslide stability analysis in order to determine the stability factor of the sliding surfaces of the model slope, as shown in Fig. 11. The stability factors for sliding surfaces 1, 2, and 3 were 0.879, 0.886, and 0.867, respectively. Given that sliding surface 3 exhibited the lowest stability factor and represented the most unstable area of the entire landslide mass, it was selected as the primary sliding surface for analysis. A time-dependent curve of the stability factor for the sliding surface was developed based on the variations in stability factor before and after rainfall, as shown in Fig. 12. The data presented in Fig. 12 revealed a clear negative correlation between fluctuations in rainfall and stability factor from August 1st to August 31. At the beginning of the rainfall period, brief rainfall increased the moisture content within the landslide mass; however, due to the high permeability of the loess layer, most of the water from the initial rainfall was retained in the superficial soil and did not significantly impact the deep sliding surfaces, resulting in a relatively high stability factor. As the rainfall continued, water gradually infiltrated the deep sliding surfaces, and pore water pressure increased, leading to a significant reduction in the shear strength of the sliding surfaces. Throughout mid-to-late August, rainfall reached multiple peaks, which correspondingly reduced the effective stress at the sliding surfaces and significantly decreased the stability factor, especially on August 31, when it dropped below 1.0. At the end of the scenario, the stability factor continued to decline; even after the rainfall decreased, it did not recover quickly. This lag effect indicated that stability is not immediately restored following rainfall infiltration into the sliding surfaces. The slow evaporation and drainage of water from the loess layer contributed to the prolonged release of pore water pressure; therefore, the sliding surfaces remained in a relatively unstable state.

This instability is mechanistically linked to the critical pore water pressure thresholds within the loess layer. When pore pressures exceeded approximately 30 kPa—a range derived from the Mohr-Coulomb failure criterion—the effective normal stress along the sliding surface decreased significantly, directly reducing shear strength and triggering instability. A time-dependent stability factor curve for sliding surface 3 revealed a clear inverse relationship between rainfall intensity and slope stability from August 1st to 31st. Three distinct phases of mechanical behavior were identified. During the initial rainfall period, limited infiltration occurred due to the high permeability of the loess layer, confining moisture to the upper 1.5 m of soil and maintaining a stability factor above 1.2. As cumulative rainfall surpassed 150 mm by mid-August, progressive saturation of the soil profile allowed pore pressure propagation to reach the sliding surface at a depth of 8 m. The critical phase occurred in late August when peak pore pressures of 112.76 kPa coincided with a 35% reduction in effective stress, driving the stability factor below 1.0.

Conclusions

-

1.

Rainfall-induced infiltration triggered a dual destabilization mechanism through matric suction degradation and seepage force activation. The progressive loss of unsaturated soil suction above the groundwater table directly weakened interparticle bonding forces, causing a synchronous reduction in shear strength across the landslide mass. Concurrently, downslope-directed seepage flow generated hydrodynamic pressure that amplified the sliding force vector, establishing a positive feedback loop between strength deterioration and stress intensification. Notably, the migration of fine particles through preferential flow paths induced microstructural collapse through seepage erosion, creating localized failure conduits that accelerated macroscopic instability through hydraulic-mechanical coupling effects.

-

2.

Prolonged rainfall drove a characteristic three-phase water redistribution process, as evidenced by the stepwise growth pattern of the volumetric water content curve. This staged saturation process first expanded existing fractures through hydro-fracturing mechanisms, then enhanced permeability via connectivity of enlarged pores, and ultimately triggered loess disintegration through clay mineral swelling. The resulting structural degradation exhibited time-dependent characteristics, where shear strength reduction progressed from initial suction loss (Phase I) to particle bond dissolution (Phase II), culminating in complete fabric collapse (Phase III). Such hydration-induced metamorphosis fundamentally altered the hydro-mechanical properties of the loess-mudstone interface, establishing a critical pathway for catastrophic strength deterioration.

-

3.

This study developed an analytical formulation for pore water pressure variation under rainfall infiltration conditions, validated its accuracy through rigorous numerical simulations, and established a novel theoretical framework for investigating rainfall-induced destabilization mechanisms in landslides. The derived model demonstrates less than 7.5% deviation from field-monitored pore pressure data, significantly advancing quantitative assessment of hydraulic-mechanical coupling effects on slope stability.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Huang, R. Q. Large landslides and their mechanisms in China since the 20th century. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 26 (3), 433–454 (2007).

Yang, B. et al. A Chinese named entity recognition method for landslide geological disasters based on deep learning. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 139 (PA), 109537–109537 (2025).

Stanley, A. T. et al. Landslide hazard is projected to increase across high mountain Asia. Earth’s Future. 12 (10), e2023EF004325–e2023EF004325 (2024).

Meng, Z. J. et al. Simulation of the initiation mechanism of rainfall-triggered loess landslides. J. Earth Sci. Environ. 45 (3), 474–484 (2023).

Abdulahi, M. M. & Egli, E. P. Landslides triggered by the July 21–22, 2024, heavy rainfall in the Gofa zone, Southern Ethiopia. Landslides 22 (1), 1–4 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Landslides triggered by the extreme rainfall on July 4, 2023, Wanzhou, China. Landslides (prepublish), 1–13. (2024).

Maturidi, M. A. M. A. et al. Rainfall-induced landslide thresholds development by considering different rainfall parameters: A review. J. Ecol. Eng. 22 (10), 85–97 (2021).

Jinchang, C. et al. Failure mechanism investigation on loess–mudstone landslides based on the Hilbert–Huang transform method using a large-scale shaking table test. Eng. Geol. 302. (2022).

Gang, X. W. et al. Trigger mechanism of loess-mudstone landslides inferred from ring shear tests and numerical simulation. J. Mountain Sci. 18 (9), 2412–2426 (2021).

Zhou, S. et al. Investigation of a loess-mudstone landslide and the induced structural damage in a high-speed railway tunnel. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 79 (prepublish), 1–12 (2020).

Mu, W. et al. Triggering mechanism and reactivation probability of loess-mudstone landslides induced by rainfall infiltration: a case study in Qinghai Province, Northwestern China. Environ. Earth Sci. 79 (1), 1–19 (2020).

Peng, J. et al. Development of a loess-mudstone landslide in a fault fracture zone. Environ. Earth Sci. 75 (8). (2016).

Wei, L. et al. Hydraulic property variations with depth in a loess mudstone landslide. Sci. Rep. 14 (1). (2024).

Jian, R. et al. Experimental study on the failure mechanism of the Zhoujiashan landslide under the combined effect of rainfall and earthquake in Tianshui City, Northwest China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82 (12). (2023).

Tengfei, Y. et al. On seismic response of loess-mudstone slope with underlying anti-dip fault zone: laboratory investigation using shaking table test. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82 (4). (2023).

Xiangning, J. et al. Seismic response of loess-mudstone slope with high anti-dip angle fault zone. Appl. Sci. 12 (13), 6353–6353 (2022).

Shuanhu, L. et al. Multiscale nonlinear analysis of failure mechanism of loess-mudstone landslide. Catena 213. (2022).

Li, S. et al. Interdisciplinary asperity theory to analyze nonlinear motion of loess landslides with weak sliding interface. Landslides 17 (12), 1–9 (2020).

Sun, P. et al. Earthquake-triggered landslides by the 1718 Tongwei earthquake in Gansu Province, Northwest China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 76 (4), 1281–1295 (2017).

Nai, W. et al. Characteristic and stability analysis for loess seismic landslide in Valley City. Adv. Mater. Res. 2091 (594–597), 1856–1863 (2012).

Xue, C. et al. Formation mechanism of loess-mudstone landslides in the Weibei tableland fault active zone of Baoji, China - taking Wolongsi landslide as an example. Geomorphology 460109284 (2024).

Wenbin, C., Aiguo, X. & Ping, W. Initiation mechanism of an earthquake-triggered loess-mudstone interface landslide: insights from DEM numerical simulation. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 83 (7). (2024).

Jinchang, C. et al. Investigating the failure mechanism of loess-mudstone landslides with a high water content interface subjected to earthquakes through the shaking table test. Soil. Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 177108406 (2024).

Ohtsuka, S. & Miyata, Y. Failure mechanism of clay in pore water pressure loading test. Landslides 37 (4), 10–171 (2001).

Ma, Z. J. et al. Mechanism and stability analysis of loess-mudstone contact landslides under seismic action. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 45 (4), 810–818 (2023).

Bao, J. Study on the soil-water Characteristic Curve of Undisturbed Loess in Jingyang, South Yuan (Chang’an University, 2017).

Fredlund, D. G. & Rahardjo, H. Hillside slope stability assessment in unsaturated residual soils. In IKRAM Seminar on the Geotechnical Aspects of Hillside Development 6 23–35. (1994).

Xu, D. Z. Numerical Simulation and Stability Analysis of rainfall-induced Seepage in Expansive Soft Rock Landslides (Jilin University, 2013).

Funding

The funding details are as follows:

- Funding Project Name: Geological Disaster Risk Assessment Based on Machine Learning and Multi-source Data Fusion

- Project Number: SKLGP2025K030

- Sponsor: National Key Laboratory of Geological Disaster Prevention and Geological Environmental Protection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D. and X.L. framed the study plan and wrote the paper.X.L., C.T. and Y.P. conducted relevant field research and visits.J.D. and J.Z. conducted article data processing.Y.P., J.Z. and Z.W. feedback on the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Dong, J., Tang, C. et al. Instability mechanism of loess-mudstone landslides under rainfall infiltration conditions. Sci Rep 15, 17591 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01887-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01887-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Shear strength and deformation characteristics of corn husk fiber-reinforced loess

Scientific Reports (2025)