Abstract

The selection of suitable AI models to predict disability diseases stands as a vital multi-attribute decision-making (MADM) task within healthcare technology. The current selection methods fail to integrate the management of uncertainties with bipolarity while also handling additional fuzzy information and linguistic terms during decision-making which leads to inferior model choices. To address these limitations, this paper proposes a new MADM approach within the environment of bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic sets (BCFLSs). In this manuscript, our primary contributions include, the proposal of four new Maclaurin symmetric mean (MSM) operators, in the setting of BCFLSs, analysis of properties of these operators to build the theoretical framework, development of a novel MADM approach to address uncertainties, bipolarity (dual aspects), addition fuzzy information; and linguistic terms (LTs), and application of the interpreted methodology to handle a real-life case study containing AI model selection for predicting disability disease. The case study of disability disease prediction results shows TensorFlow Neural Network achieved superior performance than other AI models with a score value of 7.776 using bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic MSM (BCFLMSM) and 1.943 using bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic weighted MSM (BCFLWMSM) operators while Support Vector Machine delivered the highest score (0.44 with bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic dual MSM (BCFLDMSM) and 0.006 with bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic weighted dual MSM (BCFLWDMSM) operators) based on different attribute interrelationships. Comparing the presented approach with the existing methodologies shows that the proposed approach is more efficient for handling complex decision situations. The findings suggest that our method offers more robust and accurate assessments by taking into account different aspects of uncertainty and system intricacy in the decision-making context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Disability disease prediction by Artificial Intelligence models can be described as elaborate algorithms aimed at processing medical data and finding markers of the disease with high accuracy. These complex algorithmic systems use large volumes of medical data such as patient history, genetic information, clinical evaluations, imaging studies, and physiological monitoring to derive the prognosis of disability-related conditions. While using diagnostic models, which are based on AI, it is possible to analyze multiple parameters at once, and the algorithm will be able to identify connections that are not quite noticeable to the human eye. These models become especially useful for disability diseases that are determined by neurological, genetic, and environmental factors. They can combine streams of data of an individual, like neuroimaging scans, genetic sequencing data, patient diary of symptoms, and patient long-term health records to develop high-level prognostic models. These models use several forms of artificial intelligence such as deep neural networks, support vector machines, decision trees, and ensemble learning algorithms for many machine learning tasks encompassing probability of disease manifestation, disease progression rates, and possible therapeutic approaches. The basic purpose of such AI models is not just a diagnostic tool per se but also to use diagnostic data to construct early warning systems that may be able to arrest or perhaps contain diseases with proper medical intervention.

The decision-making process of selecting an appropriate AI model for predicting disability diseases turns out to be a classic example of an MCDA problem because of the complexity and the multiple criteria involved in the decision-making process. Those who are involved in decision-making processes in the field of healthcare technology work in an environment in which no one factor can be used to assess the appropriateness of an AI model. The MCDM approach emerges as critical since it enables an integrated evaluation of several, and sometimes competing, criteria at once. When applied to disability disease prediction, decision experts are faced with several conflicting goals such as prediction accuracy, computational cost, model explainability, and transferability across different populations. The traditional decision-making models are insufficient to solve the problem because they do not allow for the proper consideration of these multiple attributes and their trade-offs. An AI model may possess high predictability, but it may consume a lot of computational power, or it may be very explainable but less accurate. The MCDM framework offers a systematic approach to measure these competing dimensions in both a quantitative and qualitative way so that the decision-makers can develop an effective scoring system that is more sophisticated than the mere linear trade-off. Using AHP, TOPSIS, or WASPAS, for instance, healthcare technology experts can create a sound, justified, and unchallengeable approach to choosing the right AI model. This approach recognizes that the selection is not about searching for the ideal model but looking for the best solution that provides the best fit of several important performance measures in the context of disability diseases.

The information or data is becoming more complicated with the development of the world and over time. Thus, the notion of a crisp set was not enough to handle such tricky and awkward information or data, Therefore, Zadeh1 described the fuzzy set (FS) theory. Each element of FS has a membership degree (MD) between \(0\) and \(1\), including \(0\) and \(1\). Afterward, numerous scholars employed this FS in various disciplines. FS has demonstrated encouraging and powerful contributions to human-based knowledge to accomplish advancements in multiple departments, such as image coding, data analysis, intelligence systems, etc. FS can successfully manage a wide range of issues of genuine life through collaboration, which might be past the capacity of traditional methods. Thus, FS could deal with numerous problems, such as DM, processing information, optimization, pattern recognition, etc. Zhou and Wang2 interpreted the fuzzy order (FO) equivalent class. The classification in a server-to-client architecture based on fuzzy relation (FR) inequality was investigated by Xiao et al.3. Behzadipour et al.4 devised a hierarchical dynamic group decision approach within FS. Raiabpour et al5 initiated fuzzy AHP and DEMATEL for type 2 fuzzy and Saranya and Saravanan6 diagnosed fuzzy DRASTIC and fuzzy DRASTIC-L. Gitinavard et al.7 devised a ranking and balancing approach within hesitant FS and Gitinavard and Zarandi8 discussed the soft computing method with hesitant FS. Borujeni et al.9 devised a group decision analysis within intuitionistic FS. A mixed expert assessment approach and group outranking technique for interval-valued hesitant FS were interpreted by Gitinavard and Zarandi10 and Gitinavard et al.11 respectively. Various scholars generalized FS, and the notion of bipolar fuzzy (BF) set (BFS) is one of the generalizations of FS diagnosed by Zhang12 to overcome the lack presented in the structure of FS, i.e., the negative aspects. Each element of the BF set has a positive membership degree (PMD) between \(0\) and 1, including \(0\) and 1 as well as a negative membership degree (NMD) between \(-1\) and \(0\), including \(-1\) and \(0\). The BF set is utilized in graph theory by various scholars such as Poulik and Ghorai13 initiated graphs complete degree, Akram14 defined BF graphs and their applications, Rajeshwari et al.15 initiated BF graphs on topological indices, Lu et al.16 diagnosed cyclic connectivity index of BF incidence graph, Sarwar and Akram et al.17 explored BF competition graphs. Singh18 interpreted the BF notions reduction utilizing granular-based weighted entropy. Abughazalah et al.19 described certain ideals in BCI algebra by employing the BF set. Alghamdi et al.20 initiated BF BCK submodules. For the BF set, a lot of scholars defined various methods such as Garai et al.21 and Alghamdi et al.22 defined multi-criteria DM (MCDM), Zhao et al.23 initiated the CPT-TODIM method, Akram and Arshad24 defined TOPSIS and ELECTRIC-I, and Akram and Al-Kenani25 defined ELECTRE-II. Also, certain researchers investigated AOs for BF sets like Riaz et al.26 initiated trigonometric AOs, and Jana et al.27,28 explored Dombi and prioritized AOs. Zararsiz and Riaz29 developed BF metric spaces. Jamil and Riaz30 initiated TPOSIS and ELECTRE-I for the cubic BF set.

Another generalization of FS is the complex fuzzy (CF) set investigated by Ramot et al.31 to overcome the deficiency, presented in the structure of FS i.e. 2nd dimension (extra fuzzy information). Each element of the CF set has MD within a unit circle of a complex plane. Tamir et al.32 also examined the CF set and considered a unit square in a complex plan for each MD. The MD is of polar form in the notion defined by Ramot et al.31 and in the shape of cartesian form in the notion of Tamir et al.32. Singh33 investigated crisply generated CF concepts analysis employing Shannon entropy. Hu et al.34 presented homogeneity of CF operations. Khan et al.35 investigated signal processing under the CF setting. Bi et al.36,37 propounded arithmetic and geometric AOs. After that, Mahmood and Rehman38 further generalized the FS notion and constructed a bipolar complex fuzzy (BCF) set (BCFS) to overcome the deficiencies, presented in the structure of FS i.e. 2nd dimension (extra fuzzy information) and negative aspects of the information. Each element of the BCF set has PMD within the first quadrant of the unit square as well as NMD within the third quadrant of the unit square of a complex plane. Rehman and Mahmood39 described generalized dice similarity measures (SMs) for the BCF set. Mahmood et al.40 introduced AOs under the BCF setting. Ur Rehman et al.41 introduced an analytical hierarchy process for BCF set under frank AOs. Mahmood et al.42 defined Bonferroni mean operators for BCF sets. Dombi and Hamacher AOs for BCF sets are investigated by Mahmood and Rehman43 and Mahmood et al.44 respectively. The notion of the BCF soft set was introduced by Mahmood et al.45.

Motivation and research problem

The current method of selecting AI models for disability disease prediction lacks sufficient solutions to handle multiple uncertainties that appear during decision-making processes. This research examines a fundamental problem given as follows

“How does an integrated bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic framework enhance disability disease prediction model selection accuracy through simultaneously addressing uncertainty, bipolarity, extra fuzzy information, and linguistic imprecision?”

In the current approach to selecting AI models for predicting disability diseases, a major gap is that the decision-making (DM) process involves various uncertainties and bipolarity that are not well addressed, such as Kumar et al.46 devised a MCDM for disease prediction, Freitas47 devised multi-criteria technique for predicting and diagnosing mental disabilities, Lin et al.48 discussed machine learning approach for predicting disease status, Kumar et al.49 devised a MCDM approach for disease prediction. These unaddressed aspects form a big problem when it comes to model selection. In many cases, the attributes that are involved in the selection process are ambiguous, have a bipolar nature, may contain extra information, and use linguistic terms that are not fully addressed in the existing selection methodologies. The previous strategies for selecting models for disability disease prediction have been mainly conventional and do not incorporate the DM processes adequately. The current AI model selection processes depend on deterministic approaches without sufficient capability to handle complexities that include attribute vagueness measurement bipolar evaluation criteria and extra fuzzy information and linguistic terms. The lack of these essential dimensions leads to an insufficient method for choosing AI models that predict disability diseases. The current decision-making methods show inherent limitations because they miss essential facets needed for good decision processes. This research develops a new MADM approach that provides an enhanced realistic framework for decision-making. The new model employs systematic methods to handle vague information while integrating bipolarity additional fuzzy data and linguistic term interpretation. The approach delivers a wider strategic framework for model selection which includes contextual awareness. This paper emphasizes the necessity of developing such an advanced approach. The selection of AI models for predicting disability diseases becomes fundamentally flawed and potentially suboptimal when this approach is absent. This proposed method for MADM technology delivers an improved approach to model selection in medical research because it creates more accurate assessments of suitable AI solutions.

Further, because of the socioeconomic environment’s growing difficulty and the inherent subjectivity of human thought, numerical data may not always be sufficient to address ambiguous and unclear data in real-life DM dilemmas, particularly when it comes to qualitative factors. However, giving the evaluation values in the shape of linguistic variables (LVs) is much easier. Thus, Zadeh50 described the notion of linguistic terms (LTs) set (LTS). Peng et al.51 investigated an interactive fuzzy LT set. Wang et al.52 introduced intuitionistic linguistic (IL) AOs, and Ju et al.53 initiated IL AOs based on MSM. Erol et al.54 investigated hesitant fuzzy LT sets. Geo et al.55 presented an interval-valued bipolar uncertain linguistic set. The theory of MSM can explore the interrelationship among the input arguments, which is the main difference between MSM operators from other AOs. The conception of MSM is a significant and impressive technique for handling DM issues. In the last few years, MSM got a lot of attention in the setting of FS such as Qin and Liu56 explored MSM AOs for intuitionistic FS (IFS), Wei and Lu57 initiated MSM AOs for Pythagorean FS (PFS), etc. Moreover, the already defined MSM operators have only the capability of aggregating the data in the structure of crisp, IFS, PFS, ILFS, etc., but are unproductive in the circumstances where the information or data is in the structure of BCFLS. Further, this article develops an extension of the new MADM method and MSM operators within the BCFLS framework. Multiple generalized frameworks of fuzzy sets exist in literature with unique benefits like neutrosophic sets58 which enable direct modeling of indeterminacy by employing an additional membership function. Various scholars have contributed to neutrosophic theory, such as Ali and Smarandache59 interpreted complex neutrosophic sets, and Broumi60 devised the concept of neutrosophic graphs. Our research concentrates on both positive and negative aspects of the criteria along with linguistic terms but neutrosophic sets fail to address the negative aspects of the criteria and linguistic terms despite their many advantages. The article uses BCFLSs because this framework meets the requirements needed to achieve our research objectives.

Contribution and novelty

This research presents bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic Maclaurin symmetric mean (BCFLMSM) operators for MCDM which serve as a modern solution for selecting optimal AI models for disability disease prediction while handling uncertainty alongside bipolarity and additional fuzzy information and linguistic assessments. This research has the following novel contributions.

-

MSM operators within BCFLS: This paper introduces four pioneering operators known as bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic MSM (BCFLMSM), weighted MSM (BCFLWMSM), Dual MSM (BCFLDMSM), and weighted Dual MSM (BCFLWDMSM) which provide entirely new capabilities to handle multidimensional uncertain information.

-

The theoretical foundation for decision-making within BCFLS: A strong theoretical structure exists that demonstrates the necessary mathematical aspects of these operators to ensure reliable and consistent decision-making processes in complicated BCFLS implementation.

-

Novel MADM methodology: This paper develops a complete bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic MADM (BCFL-MADM) technique that integrates four essential information processing elements:

-

Uncertainty handling through fuzzy set operations

-

Bipolarity management through positive and negative membership degrees

-

Additional fuzzy information via complex number representation

-

Linguistic term integration through specialized linguistic variables

-

-

Real-world validation: Our framework proves its excellence by applying it to disability disease prediction model selection where it generates superior results when compared to traditional methods.

The methodology we developed makes a substantial improvement to decision theory through: A mathematically sophisticated integration of advanced operators, and superior management of multifaceted information, and this framework provides an advanced solution system for addressing challenging healthcare technology selection problems The new method advances current medical AI model selection practices through its establishment of a decision-making framework which considers multiple information dimensions simultaneously.

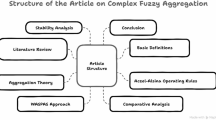

Layout of the manuscript

In “Preliminaries” section, this paper interprets the theory of BCFLS and related outcomes. In “BCF linguistic Maclaurin symmetric mean AOs” section of this paper expand the MSM in the setting of BCFLS and interpreted AOs for aggregation BCFLNs such as BCFLMSM, BCFLWMSM, BCFLDMSM, and BCFLWDMSM operators. In “Bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic MADM approach” section, contain a MADM approach based on the defined MSM operators and in the setting of BCFLS and then present a case study of the selection of an AI model for predicting disability diseases. “Comparison analysis” section compares the investigated theory with a few current theories depicting the defined conception of power and domination. The concluding remark of this manuscript is investigated in “Conclusions” section.

Preliminaries

Inspired by the conception of BCFS presented by Mahmood and Ur Rehman33, here we interpret the most valuable and meaningful conception, called BCF linguistic set (BCFLS), to give the PMD and NMD of an element to a certain LT variable at once. Let \(\mathcal{H}\) be a universal set, and \(\overline{\mathcal{S} }\) be a continuous LT set of \(\mathcal{S}=\left\{{\mathbbm{s}}_{0},{\mathbbm{s}}_{1},\dots , {\mathbbm{s}}_{\psi }\right\}\).

Definition 1

61 A BCFLS on \(\mathcal{H}\) is of the structure

where, \({\mathbbm{s}}_{\phi \left(\mathfrak{h}\right)}\in \overline{\mathcal{S} }\), \({\mu }_{P-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)={\mu }_{RP-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)+\iota {\mu }_{IP-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)\) is a PMD and \({\mu }_{N-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)={\mu }_{RN-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)+\iota {\mu }_{IN-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)\) is an NMD with \({\mu }_{RP-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right),{\mu }_{IP-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)\in \left[0, 1\right]\) and \({\mu }_{RN-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right),{\mu }_{IN-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)\in \left[-1, 0\right]\), of an element \(\mathfrak{h}\in \mathcal{H}\) to the LT \({\mathbbm{s}}_{\phi \left(\mathfrak{h}\right)}\). The set \(\mathcal{Z}=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{\phi \left(\mathfrak{h}\right)},\left({\mu }_{P-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right),{\mu }_{N-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{\phi \left(\mathfrak{h}\right)},\left({\mu }_{RP-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)+\iota {\mu }_{IP-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right), {\mu }_{RN-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)+\iota { \mu }_{IN-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)\right)\right)\), epitomized the BCFLN.

Definition 2

61 The score value (SV) of a BCFLN \(\mathcal{Z}=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{\phi },\left({\mu }_{P-\mathcal{Z}}, {\mu }_{N-\mathcal{Z}}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{\phi },\left({\mu }_{RP-\mathcal{Z}}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-\mathcal{Z}}, {\mu }_{RN-\mathcal{Z}}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-\mathcal{Z}}\right)\right)\) is discovered as

Definition 3

61 The accuracy value (AV) of a BCFLN \(\mathcal{Z}=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{\phi },\left({\mu }_{P-\mathcal{Z}}, {\mu }_{N-\mathcal{Z}}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{\phi },\left({\mu }_{RP-\mathcal{Z}}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-\mathcal{Z}}, {\mu }_{RN-\mathcal{Z}}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-\mathcal{Z}}\right)\right)\) is discovered as

The comparison laws among two BCFLNs rely on the SV \(S{L}_{SF}\) and the AV \(H{L}_{AF}\) discovered above are described below

Theorem 1

\({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{1}},\left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{1}}, \left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}\right)\right)\) and \({\mathcal{Z}}_{2}=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{2}},\left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{2}},\left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}\right)\right)\) are two BCFLNs, then

-

1.

if \({SL}_{SF}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}\right)<{SL}_{SF}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{2}\right)\), then \({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}<{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}\);

-

2.

if \({SL}_{SF}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}\right)>{SL}_{SF}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{2}\right)\), then \({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}>{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}\);

-

3.

if \({SL}_{SF}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}\right)={SL}_{SF}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}\right)\), then

-

1.

if \({HL}_{AF}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}\right)<{HL}_{AF}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{2}\right),\) then \({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}<{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}\);

-

2.

if \({HL}_{AF}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}\right)>{HL}_{AF}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{2}\right),\) then \({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}>{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}\);

-

3.

if \({HL}_{AF}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}\right)={HL}_{AF}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{2}\right),\) then \({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}={\mathcal{Z}}_{2}\).

BCF linguistic Maclaurin symmetric mean AOs

This part of the paper expands the MSM in the setting of BCFLS and interpret AOs for BCFLNs such as BCFLMSM, BCFLWMSM, BCFLDMSM, and BCFLWDMSM operators. For that, we interpret operations for BCFLNs.

Definition 4

Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{1}},\left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{1}}, \left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}\right)\right)\) and \({\mathcal{Z}}_{2}=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{2}},\left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{2}},\left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}\right)\right)\) are two BCFLNs with \(\partial >0\), then

-

\({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}\oplus {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{1}+{\phi }_{2}}\left(\begin{array}{c}{\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}+{\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}-{\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}{\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}+\iota \left({\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}+{\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}-{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}\right), \\ -\left({\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}\right)+\iota \left(-\left({\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}{\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}\right)\right)\end{array}\right)\right)\)

-

\({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}\otimes {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{1}\times {\phi }_{2}}\left(\begin{array}{c}{\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}{\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}, \\ {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}+{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}+{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}+\iota \left({\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}+{\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}{\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}+{\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}}\right)\end{array}\right)\right)\)

-

\(\partial {\mathcal{Z}}_{1}=\left(\partial \times {\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{1}},\left(1-{\left(1-{\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}\right)}^{\partial }+\iota \left(1- {\left(1-{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}\right)}^{\partial }\right),-{\left|{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}\right|}^{\partial }+\iota \left(-{\left|{\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}\right|}^{\partial }\right) \right)\right)\)

-

\({{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}^{\partial }=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{1}^{\partial }},\left(\left({\left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}\right)}^{\partial }+\iota {\left({\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}\right)}^{\partial }, -1+{\left(1+{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}\right)}^{\partial }+\iota \left(-1+{\left(1+{\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}}\right)}^{\partial }\right)\right)\right)\right)\)

BCF linguistic MSM operator

Following we introduce the BCFLMSM operator.

Definition 5

Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}, \left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}, \left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right), \left(\dot{\gimel }=1, 2, 3, \dots , \psi \right)\) is a group of BCFLNs and \(\mathcalligra{q}=1, 2, \dots , \psi\), then the BCFLMSM operator is a function \(BCFLMSM:{\mathcal{Z}}^{\psi }\to \mathcal{Z}\), explained as

where \({\complement }_{\psi }^{\mathcalligra{q}}=\frac{\psi !}{\mathcalligra{q}!\left(\psi -\mathcalligra{q}\right)!}\) is a binomial coefficient and \(\left({\mathcal{e}}_{1}, {\mathcal{e}}_{2}, \dots , {\mathcal{e}}_{\psi }\right)\) tracks \(\mathcalligra{q}-\) tuple combination of \(\left(1, 2, 3, \dots , \psi \right)\).

Theorem 2

Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}, \left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}, \left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right), \left(\dot{\gimel }=1, 2, 3, \dots , \psi \right)\) is a group of BCFLNs, then after utilizing the BCFLMSM operator the outcome is BCFLN, granted as

Proof

By employing Def (4) we have

Therefore,

The discovered BCFLMSM operator fulfills the below axioms.

Theorem 3

Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}\left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}\left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right)\) and \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }{\prime}}\left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }{\prime}}\left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}\right)\right), \left(\dot{\gimel }=1, 2, 3, \dots , \psi \right)\) are two groups of BCFLNs, then

-

1.

(Idempotency) If \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }=\mathcal{Z} \forall \gimel\), then \(BCFLMS{M}^{\left(\mathcalligra{q}\right)}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{3}, \dots , {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }\right)=\mathcal{Z}\).

-

2.

(Monotonicity) If \({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\le {\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}, {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\le {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\le {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}{\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\le {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}\), then

$$BCFLMS{M}^{\left(\mathcalligra{q}\right)}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{3}, \dots , {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }\right)\le BCFLMS{M}^{\left(\mathcalligra{q}\right)}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}^{"}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}^{"}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{3}^{"}, \dots , {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }^{"}\right).$$ -

3.

(Boundedness) Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}^{-}=\left(\underset{\gimel }{\text{min}}\left\{{\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}+\iota \underset{\gimel }{\text{min}}\left\{{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}, \underset{\gimel }{\text{max}}\left\{{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}+\iota \underset{\gimel }{\text{max}}\left\{{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}\right),\) and \({\mathcal{Z}}^{+}=\left(\underset{\gimel }{\text{max}}\left\{{\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}+\iota \underset{\gimel }{\text{max}}\left\{{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}, \underset{\gimel }{\text{min}}\left\{{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}+\iota \underset{\gimel }{\text{min}}\left\{{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}\right)\), then

$${\mathcal{Z}}^{-}\le BCFLMS{M}^{\left(\mathcalligra{q}\right)}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{3}, \dots , {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }\right)\le {\mathcal{Z}}^{+}.$$

Particular cases

Here, we discuss the special cases of the interpreted BCFLMSM operator.

Case 1: If we take \(\mathcalligra{q}=1\) in Eq. (1), then we discover the bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic average (BCFLA) operator as below

let \({\mathcal{e}}_{1}=\mathcal{e}\). Then

Case 2: If we take \(\mathcalligra{q}=2\) in Eq. (1), then we discover bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic Bonferroni mean (BCFBM) operator as below

Case 3: If we take \(\mathcalligra{q}=\psi\) in Eq. (8), then we discover the bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic geometric (BCFLG) operator as below

Let \({\mathcal{e}}_{\gimel }=\gimel\) and \(\prod_{\gimel =1}^{\psi }\left(1+{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{{\mathcal{e}}_{\gimel }}}\right)\in \left[0, 1\right]\) for all \(\gimel\), thus, \(\left|\left(1-\prod_{\gimel =1}^{\psi }\left(1+{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{{\mathcal{e}}_{\gimel }}}\right)\right)\right|=\left(1-\prod_{\gimel =1}^{\psi }\left(1+{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{{\mathcal{e}}_{\gimel }}}\right)\right),\) then

BCF linguistic weighted MSM operator

The above-discovered BCFLMSM operator doesn’t think about the significance of the attributes. However, in numerous pragmatic circumstances, particularly in MADM the weights of the attributes assume a significant part in the procedure of aggregation. To handle this, here, we discover the BCFLWMSM operator.

Definition 6

Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}, \left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}, \left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right), \left(\dot{\gimel }=1, 2, 3, \dots , \psi \right)\) is a group of BCFLNs and \(\mathcalligra{q}=1, 2, \dots , \psi\), then the BCFLWMSM operator is a function \(BCFLMSM:{\mathcal{Z}}^{\psi }\to \mathcal{Z}\), explained as

where \(\mathcal{y}=\left({\mathcal{y}}_{1}, {\mathcal{y}}_{2},\dots , {\mathcal{y}}_{\psi }\right)\) is weight vector (WV) with \(0\le {\mathcal{y}}_{\gimel }\le 1\) and \(\sum_{\gimel =1}^{\psi }{\mathcal{y}}_{\gimel }=1\) and \(\left({\mathcal{e}}_{1}, {\mathcal{e}}_{2}, \dots , {\mathcal{e}}_{\psi }\right)\) tracks \(\mathcalligra{q}-\) tuple combination of \(\left(1, 2, 3, \dots , \psi \right)\).

Theorem 4

Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}, \left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}, \left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right), \left(\dot{\gimel }=1, 2, 3, \dots , \psi \right)\) is a group of BCFLNs, then after utilizing the BCFLWMSM operator the outcome is BCFLN, granted as

Theorem 5

Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}\left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}\left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right)\) and \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }{\prime}}\left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }{\prime}}\left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}\right)\right), \left(\dot{\gimel }=1, 2, 3, \dots , \psi \right)\) are two groups of BCFLNs, then

-

1.

(Idempotency) If \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }=\mathcal{Z} \forall \gimel\), then \(BCFLWMS{M}^{\left(\mathcalligra{q}\right)}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{3}, \dots , {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }\right)=\mathcal{Z}\)

-

2.

(Monotonicity) If \({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\le {\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}, {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\le {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\le {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}{\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\le {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}\), then

$$BCFLWMS{M}^{\left(\mathcalligra{q}\right)}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{3}, \dots , {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }\right)\le BCFLWMS{M}^{\left(\mathcalligra{q}\right)}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}^{"}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}^{"}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{3}^{"}, \dots , {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }^{"}\right)$$ -

3.

(Boundedness) Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}^{-}=\left(\underset{\gimel }{\text{min}}\left\{{\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}+\iota \underset{\gimel }{\text{min}}\left\{{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}, \underset{\gimel }{\text{max}}\left\{{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}+\iota \underset{\gimel }{\text{max}}\left\{{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}\right),\) and \({\mathcal{Z}}^{+}=\left(\underset{\gimel }{\text{max}}\left\{{\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}+\iota \underset{\gimel }{\text{max}}\left\{{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}, \underset{\gimel }{\text{min}}\left\{{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}+\iota \underset{\gimel }{\text{min}}\left\{{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}\right)\), then

$${\mathcal{Z}}^{-}\le BCFLWMS{M}^{\left(\mathcalligra{q}\right)}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{3}, \dots , {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }\right)\le {\mathcal{Z}}^{+}.$$

BCF linguistic dual MSM operator

Following, we introduce the BCFLDMSM operator.

Definition 7

Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}, \left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}, \left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right), \left(\dot{\gimel }=1, 2, 3, \dots , \psi \right)\) is a group of BCFLNs and \(\mathcalligra{q}=1, 2, \dots , \psi\), then the BCFLDMSM operator is a function \(BCFLDMSM:{\mathcal{Z}}^{\psi }\to \mathcal{Z}\), explained as

where \({\complement }_{\psi }^{\mathcalligra{q}}=\frac{\psi !}{\mathcalligra{q}!\left(\psi -\mathcalligra{q}\right)!}\) is a binomial coefficient and \(\left({\mathcal{e}}_{1}, {\mathcal{e}}_{2}, \dots , {\mathcal{e}}_{\psi }\right)\) tracks \(\mathcalligra{q}-\) tuple combination of \(\left(1, 2, 3, \dots , \psi \right)\).

Theorem 6

Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}, \left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}, \left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right), \left(\dot{\gimel }=1, , 2, 3, \dots , \psi \right)\) is a group of BCFLNs, then after utilizing the BCFLDMSM operator the outcome is BCFLN, granted as

Proof

By employing Def (4) we have

Therefore,

The discovered BCFLDMSM operator fulfills the below axioms.

Theorem 7

Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}\left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}\left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right)\) and \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }{\prime}}\left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }{\prime}}\left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}\right)\right), \left(\dot{\gimel }=1, 2, 3, \dots , \psi \right)\) are two groups of BCFLNs, then

-

1.

(Idempotency) If \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }=\mathcal{Z} \forall \gimel\), then \(BCFLDMS{M}^{\left(\mathcalligra{q}\right)}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{3}, \dots , {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }\right)=\mathcal{Z}\)

-

2.

(Monotonicity) If \({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\le {\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}, {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\le {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\le {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}{\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\le {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}\), then

$$BCFLDMS{M}^{\left(\mathcalligra{q}\right)}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{3}, \dots , {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }\right)\le BCFLDMS{M}^{\left(\mathcalligra{q}\right)}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}^{"}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}^{"}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{3}^{"}, \dots , {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }^{"}\right)$$ -

2.

(Boundedness) Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}^{-}=\left(\underset{\gimel }{\text{min}}\left\{{\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}+\iota \underset{\gimel }{\text{min}}\left\{{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}, \underset{\gimel }{\text{max}}\left\{{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}+\iota \underset{\gimel }{\text{max}}\left\{{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}\right),\) and \({\mathcal{Z}}^{+}=\left(\underset{\gimel }{\text{max}}\left\{{\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}+\iota \underset{\gimel }{\text{max}}\left\{{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}, \underset{\gimel }{\text{min}}\left\{{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}+\iota \underset{\gimel }{\text{min}}\left\{{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}\right)\), then

$${\mathcal{Z}}^{-}\le BCFLDMS{M}^{\left(\mathcalligra{q}\right)}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{3}, \dots , {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }\right)\le {\mathcal{Z}}^{+}.$$

BCF linguistic weighted dual MSM operator

The above-discovered BCFLDMSM operator doesn’t think about the significance of the attributes. However, in numerous pragmatic circumstances, particularly in MADM the weights of the attributes assume a significant part in the procedure of aggregation. To handle this, here, we discover the BCFLWDMSM operator.

Definition 8

Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}, \left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}, \left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right), \left(\dot{\gimel }=1, 2, 3, \dots , \psi \right)\) is a group of BCFLNs and \(\mathcalligra{q}=1, 2, \dots , \psi\), then the BCFLWDMSM operator is a function \(BCFLWDMSM:{\mathcal{Z}}^{\psi }\to \mathcal{Z}\), explained as

where \(\mathcal{y}=\left({\mathcal{y}}_{1}, {\mathcal{y}}_{2},\dots , {\mathcal{y}}_{\psi }\right)\) is WV with \(0\le {\mathcal{y}}_{\gimel }\le 1\) and \(\sum_{\gimel =1}^{\psi }{\mathcal{y}}_{\gimel }=1\) and \(\left({\mathcal{e}}_{1}, {\mathcal{e}}_{2}, \dots , {\mathcal{e}}_{\psi }\right)\) tracks \(\mathcalligra{q}-\) tuple combination of \(\left(1, 2, 3, \dots , \psi \right)\).

Theorem 8

Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}, \left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}, \left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right), \left(\dot{\gimel }=1, 2, 3, \dots , \psi \right)\) is a group of BCFLNs, then after utilizing the BCFLWDMSM operator the outcome is BCFLN, granted as

The discovered BCFLWDMSM operator fulfills the below axioms.

Theorem 9

Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}\left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }}\left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right)\right)\) and \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }{\prime}}\left({\mu }_{P-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}, {\mu }_{N-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{{\phi }_{\gimel }{\prime}}\left({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}+\iota {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}, {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}+\iota {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}\right)\right), \left(\dot{\gimel }=1, 2, 3, \dots , \psi \right)\) are two groups of BCFLNs, then

-

1.

(Idempotency) If \({\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }=\mathcal{Z} \forall \gimel\), then \(BCFLWDMS{M}^{\left(\mathcalligra{q}\right)}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{3}, \dots , {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }\right)=\mathcal{Z}\)

-

2.

(Monotonicity) If \({\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\le {\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}, {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\le {\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\le {\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}{\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\le {\mu }_{IN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }^{"}}\), then

$$BCFLWDMS{M}^{\left(\mathcalligra{q}\right)}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{3}, \dots , {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }\right)\le BCFLWDMS{M}^{\left(\mathcalligra{q}\right)}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}^{"}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}^{"}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{3}^{"}, \dots , {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }^{"}\right)$$ -

3.

(Boundedness) Suppose \({\mathcal{Z}}^{-}=\left(\underset{\gimel }{\text{min}}\left\{{\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}+\iota \underset{\gimel }{\text{min}}\left\{{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}, \underset{\gimel }{\text{max}}\left\{{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}+\iota \underset{\gimel }{\text{max}}\left\{{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}\right),\) and \({\mathcal{Z}}^{+}=\left(\underset{\gimel }{\text{max}}\left\{{\mu }_{RP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}+\iota \underset{\gimel }{\text{max}}\left\{{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}, \underset{\gimel }{\text{min}}\left\{{\mu }_{RN-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}+\iota \underset{\gimel }{\text{min}}\left\{{\mu }_{IP-{\mathcal{Z}}_{\gimel }}\right\}\right)\), then

$${\mathcal{Z}}^{-}\le BCFLWDMS{M}^{\left(\mathcalligra{q}\right)}\left({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{3}, \dots , {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }\right)\le {\mathcal{Z}}^{+}$$

Bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic MADM approach

Consider that there are \(\psi\) number of alternatives i.e. \(\mathcal{Z}=\left\{{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}, {\mathcal{Z}}_{2},.., {\mathcal{Z}}_{\psi }\right\}\) and \(\tau\) number of attributes \(\mathfrak{N}=\left\{{\mathfrak{N}}_{1}, {\mathfrak{N}}_{2},\dots ,{\mathfrak{N}}_{\tau }\right\}\) with WV \(\mathcal{y}=\left({\mathcal{y}}_{1}, {\mathcal{y}}_{2},\dots , {\mathcal{y}}_{\tau }\right)\) and \(0\le {\mathcal{y}}_{\varsigma }\le 1\) and \(\sum_{\varsigma =1}^{\tau }{\mathcal{y}}_{\varsigma }=1\). Keep in mind these attributes the expert or specialist would describe his/her opinion (information) against each alternative in the structure of BCFLS that is \(\mathcal{Z}=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{\phi \left(\mathfrak{h}\right)},\left({\mu }_{P-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right),{\mu }_{N-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)\right)\right)=\left({\mathbbm{s}}_{\phi \left(\mathfrak{h}\right)},\left({\mu }_{RP-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)+\iota {\mu }_{IP-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right), {\mu }_{RN-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)+\iota { \mu }_{IN-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)\right)\right)\) and form a decision matrix (D-M). Now to get the result, we designate the following stages.

Stage 1: If the data belonging to the decision matrix is benefit sort then the normalization process is not obligatory but if the data belonging to the decision matrix is cost sort then the normalization process is obligatory and would be done by the underneath formula

where, \({\left({\mu }_{P-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right),{\mu }_{N-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)\right)}^{c}=\left(1-{\mu }_{RP-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)+\iota \left(1-{\mu }_{IP-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)\right), -1-{\mu }_{RN-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)+\iota \left(-1-{ \mu }_{IN-\mathcal{Z}}\left(\mathfrak{h}\right)\right)\right)\).

Stage 2: This stage contains the aggregated values of the decision matrix or normalized decision matrix determined by employing one of the defined BCFLMSM, BCFLWMSM, BCFLDMSM, and BCFLWDMSM operators.

Stage 3: Attain the SV through Def (8), and in case the SVs of any two alternatives become the same, then attain accuracy value (AV) through Def (9).

Stage 4: List the ranking of alternatives relying on the attained SVs and AVs.

The flowchart of the proposed method is shown in Fig. 1.

Case study

Over the years, however, the healthcare industry has been experiencing a dramatic transformation, particularly in the use of artificial intelligence in diagnosis and preventive medicine. As a result of the multifactorial and multifaceted nature of disability diseases, diagnostic difficulties have long been observed in the early stages of the disease. In those chronic and complex diseases, conventional diagnostic approaches may fall short since the etiologic and pathophysiologic features are complex and not easy to detect and capture; hence, appreciated delays in their management and unfavorable patient outcomes. Disability diseases are on the increase across the world and this has called for better diagnostic techniques. As per the latest trends in epidemiological research, diseases like multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, and other neurodegenerative diseases, have been on the rise, especially among the elderly. Not only does it signal morbidity in patient populations, but also creates a significantly high cost to overall global health economies. Recent and ongoing advancements in the field of machine learning especially in artificial intelligence have created new vistas in medical science. These technologies provide capabilities that are new in the way they can identify patterns, analyze data, and make predictions. However, the healthcare sector faces a critical challenge: choosing the right AI model that can best suit disability disease prediction in this complex world.

A healthcare research institution seeks to identify the best AI model for predicting disability diseases because the selection of the model greatly influences early detection, patient care, and resource utilization. The decision expert of the healthcare research institution analyzed different AI models for disability disease prediction. After careful assessment and the first round of selection, they decided to focus on four promising approaches for medical prediction tasks, interpreted in Table 1.

The evaluation of disability disease prediction models includes four AI systems which are presented in Table 1. Each model offers distinct capabilities: TensorFlow Neural Network excels at handling non-linear relationships in medical data and image-based diagnosis; Random Forest Classifier demonstrates strong resistance to overfitting with excellent feature importance analysis; Support Vector Machine effectively manages high-dimensional data spaces with strong classification capabilities; and XGBoost combines multiple small prediction models to create a powerful predictive tool that performs well with unbalanced medical data. Multiple AI-based disease prediction methods exist as the leading approaches in modern medical diagnostics.

After the selection of alternatives, the decision maker very thoroughly identified the key attributes that would be used to make the evaluation. These attributes were selected following a series of consultations with medical practitioners, data scientists, and healthcare technology specialists to ensure the assessment was holistic. These attributes are devised in Table 2.

Table 2 describes the four essential attributes that serve as fundamental evaluation criteria for medical AI model assessment. The fundamental performance metrics that matter in medical diagnostics are measured through Prediction Accuracy by assessing sensitivity and specificity. Computational Efficiency determines the necessary resource utilization which proves essential for healthcare implementation. Medical practitioners develop trust in AI models through their ability to understand model operations. Generalizability assesses how well AI models perform when treating patients of multiple backgrounds with various healthcare backgrounds. A group of multidisciplinary experts carefully chose these evaluation attributes through consultation to establish a complete assessment framework.

As attributes contain the bipolarity and extra fuzzy information, thus, the assessment values of these AI models will be in the BCFLN that is revealed in Table 3. Also, the expert interprets the weight vectors to the attributes that are \(\left(0.3, 0.1, 0.3, 0.4\right)\).

Table 3 presents the complete assessment values for each AI model regarding the four attributes through bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic numbers (BCFLNs). The assessment values include both positive and negative membership degrees and additional fuzzy information presented through complex numbers which provide enhanced expert evaluation capabilities. The weight vector \((0.3, 0.1, 0.3, 0.4)\) demonstrates the relative significance of each attribute where Generalizability stands as the most important followed by Prediction Accuracy and Interpretability which share equal importance, and Computational Efficiency holds the least significance.

Stage 1: As the data in Table 3 is beneficial sort, there is no need for stage 1.

Stage 2: This stage established the aggregated values of the data portrayed in Table 3 by employing defined BCFLMSM, BCFLWMSM, BCFLDMSM, and BCFLWDMSM operators as described in Table 4.

Table 4 shows the aggregated evaluation results from applying the four proposed operators BCFLMSM, BCFLWMSM, BCFLDMSM, and BCFLWDMSM. The evaluation data from multiple dimensions gets transformed into unified comprehensive values through each aggregation approach according to the results. Each aggregation method demonstrates different priorities in evaluation criteria which produces a more well-rounded analysis than using a solitary operator evaluation approach.

Stage 3: Attained the SVs through score function and interpreted in Table 5 and graphically interpreted in Fig. 2.

The score values from Table 5 represent the complete performance metrics of each AI model across all attributes. Model \({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}\) (TensorFlow Neural Network) produces superior performance scores of 7.776 and 1.943 when BCFLMSM and BCFLWMSM operators are utilized. The Support Vector Machine operator (Model \({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}\)) demonstrates superior performance when using BCFLDMSM and BCFLWDMSM operators but achieves this result with reduced margins. The results show that model selection choices depend heavily on aggregation methods because different operators affect which models get chosen for implementation.

The score values of each AI model appear in Fig. 1 across the four aggregation operators. The performance data in Fig. 1 demonstrates that Model \({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}\) stands out with BCFLMSM evaluation but displays similar results with other aggregation operators. The visual display provides action-makers with immediate recognition of performance trends as well as pairwise model ranking achievements under multiple evaluation metrics.

Stage 4: The ranking of alternatives relying on the attained SVs is shown in Table 6.

The score values and ranking devised in Tables 5 and 6 provide that according to BCFLMSM and BCFLWMSM operators, the AI model \({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}\) is the most suitable one and according to BCFLDMSM and BCFLWDMSM operators, \({\mathcal{Z}}_{3}\) is the most suitable one.

The case study outcomes provide vital information about selecting AI models for disability disease prediction through detailed examination. The evaluation results show that TensorFlow Neural Network achieved top performance under BCFLMSM and BCFLWMSM operators with scores of \(7.776\) and \(1.943\) but Support Vector Machine demonstrated superior results through BCFLDMSM and BCFLWDMSM operators with scores of \(0.44\) and \(0.006\). The selection outcomes depend heavily on the evaluation framework’s mathematical structure which demonstrates that healthcare institutions need to evaluate their specific needs when selecting evaluation methodologies. The authors stress that their approach which handles uncertainty alongside bipolarity additional fuzzy information and linguistic imprecision matches the complex medical diagnosis process where doctors manage competing priorities. The better match of decision-making methods to real-life complex situations results in more precise selection processes. Decision-makers need to implement specific multi-dimensional evaluation systems instead of standard single-factor evaluation procedures to obtain better diagnostic capacities that enhance patient results. The paragraph should appear in the “Conclusions” section before future work discussions to establish a link between mathematical results and healthcare practicality.

Sensitivity analysis

Here, we analyze the sensitivity of the proposed method by changing the assessment values of the alternatives based on the criteria given in the case study. The new assessment values are devised in Table 7 and the new eight of each criterion are \(0.1, 0.3, 0.4,\) and 0.2 respectively.

Now to solve this data, we again use the invented method, and the result is displayed in Table 8 and Fig. 3

The solution of new assessment values showed that by aggregating the information through BCFLMSM and BCFLWDMSM operators \({\mathcal{Z}}_{3}\) is the finest alternative and using the BCFLWMSM operator \({\mathcal{Z}}_{4}\) is the finest alternative and employing the BCFLDMSM operator \({\mathcal{Z}}_{2}\) is the finest one. We can also observe that by changing the assessment values we achieved different results. This implies that, when the data is changed the proposed approach will give different and accurate results.

Comparison analysis

This section compares the investigated theory with a few current theories depicting the defined conception of power and domination. For this purpose, we consider the approaches and AOs investigated by Wang et al.52, Ju et al.53, Gao et al.55, and Mahmood et al.44 and the defined approach and MSM AOs. Table 9 contains the results after utilizing the considered approaches and operators, and Table 10 contains their ranking order.

Wang et al.52 investigated AOs and DM approach and Ju et al.54 AOs based on MSM and DM approach in the setting of intuitionistic fuzzy LS (IFLS). The theory of IFLS can’t model the data with extra information and negative aspects. Thus, it is clear that these operators and approaches are unproductive for the data displayed in Table 3. Gao et al.55 investigated a DM approach in the setting of interval-valued bipolar uncertain LS (IVBULS). The theory of IVBULS can’t model the data with 2nd dimension. Thus, the interpreted approach is unproductive for the data displayed in Table 3. Mahmood et al.44 investigated Hamacher AOs and DM techniques for BCFS. The theory of BCFS can model both extra information and negative aspects but in this theory, the LT is missing thus, BCFS is unproductive for data in Table 3. These current approaches and operators are unproductive in the detection and diagnosis of lung cancer in a patient. The defined conception and approach are productive for the data initiated in Table 1. The result is displayed in Table 9 along with the ranking in Table 10 and Fig. 4. According to BCFLMSM and BCFLWMSM operators, the patient has lung nodules and according to BCFLDMSM and BCFLWDMSM operators, the patient has small cell lung cancer. Therefore, the initiated conception is more generalized and richer.

Conclusions

The selection of appropriate AI models for disability disease prediction needs decision-making tools that handle various uncertainties and information types. The research addresses this essential knowledge gap through a new framework that handles various dimensions of uncertainty and complexity within DM processes. The current research delivers multiple theoretical and practical advancements to MADM research. The BCFL setting benefits from the new MSM operators which include BCFLMSM, BCFLWMSM, BCFLDMSM, and BCFLWDMSM to tackle complex DM situations. The operators demonstrate strong mathematical reliability and create an extensive structure to unite multiple information types. A comprehensive theoretical foundation exists for implementing these operators in real-world DM situations because of their characteristic analysis. The MADM technique showed better performance than traditional methods because it managed to process uncertainties alongside bipolarity and additional fuzzy information and linguistic terms simultaneously. The disability disease prediction case study demonstrated TensorFlow Neural Network as the superior choice through its score values of \(7.776\) (BCFLMSM) and \(1.943\) (BCFLWMSM) while Support Vector Machine achieved the best results under BCFLDMSM and BCFLWDMSM operators with scores of \(0.44\) and \(0.006\) respectively. Our proposed method captures subtle performance differences through its \(7.776\) score difference between the TensorFlow model and SVM model operating under BCFLMSM statistically. The model ranking order under BCFLMSM and BCFLWMSM operators follows \({\mathcal{Z}}_{1}>{\mathcal{Z}}_{4}>{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}>{\mathcal{Z}}_{3}\) while BCFLDMSM and BCFLWDMSM operators produce the opposite ranking pattern of \({\mathcal{Z}}_{3}>{\mathcal{Z}}_{4}>{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}>{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}\) and \({\mathcal{Z}}_{3}>{\mathcal{Z}}_{1}>{\mathcal{Z}}_{4}>{\mathcal{Z}}_{2}\) respectively. The framework shows its capability to analyze models through multiple perspectives which gives decision-makers complete insights to make technology selection decisions. This is evident from our case study on the use of AI model selection for disability disease prediction. The results indicate that our method yields more accurate and diverse evaluations than conventional methods, especially when applied to realistic medical decision-making situations. These implications are significant for theoretical research and practical use in healthcare technology management decisions. The framework we have presented gives the decision-makers a better tool to evaluate the AI models, which may result in better effectiveness in the prediction and management of disability diseases. The work presented in this paper makes a valuable research contribution both for enhancing the theoretical developments of MADM methodologies and for applying them to the selection of healthcare technology. The proposed approach can be a more suitable and accurate guide to making crucial decisions in medical technology implementation than the current methods, which may lead to enhanced patient care results due to the selection of the right AI model.

Limitation and future direction

The framework shows various limitations that reduce its effectiveness for real-time clinical implementation through its expert-driven methodology and dependent parameters. Further, the proposed work can’t handle the information of various other mathematical structures such as complex intuitionistic FS (CIFS)62, complex hesitant fuzzy rough set CHFRS63, spherical fuzzy rough set (SFRS)64, dual hesitant FS (DHFS)65, etc. Thus, in the future, we aim to address these limitations and expand the proposed theories in other mathematical frameworks such as CHFRS, CIFS, SFRS, and DHFS, etc. Moreover, in the future, we would like to integrate the notion of bipolar complex fuzzy set (BCFS) and neutrosophic set to develop the notion of neutrosophic BCFS. Also, we aim to expand this work in the framework of Heptapartitioned neutrosophic soft set66, and interval neutrosophic sets67.

Data availability

The data utilized in this manuscript are hypothetical and artificial, and one can use these data before prior permission by just citing this manuscript. For data one can contact the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- MADM:

-

Multi-attribute decision-making

- BCFLS:

-

Bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic set

- LTs:

-

Linguistic terms

- MSM:

-

Maclaurin symmetric mean

- BCFLMSM:

-

Bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic Maclaurin symmetric mean

- BCFLWMSM:

-

Bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic weighted Maclaurin symmetric mean

- BCFLDMSM:

-

Bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic dual Maclaurin symmetric mean

- BCFLDWMSM:

-

Bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic dual weighted Maclaurin symmetric mean

- DM:

-

Decision-making

- MD:

-

Membership degree

- PMD:

-

Positive membership degree

- NMD:

-

Negative membership degree

- FS:

-

Fuzzy set

- CF:

-

Complex fuzzy

- BFS:

-

Bipolar fuzzy set

- BCFS:

-

Bipolar complex fuzzy set

- AOs:

-

Aggregation operators

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

References

Zadeh, L. A. Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control 8(3), 338–353 (1965).

Zhou, W. & Wang, M. Fuzzy order equivalent class with uncertainty. J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 14(2), 231–239 (2005).

Xiao, G., Hayat, K., & Yang, X. Evaluation and its derived classification in a Server-to-Client architecture based on the fuzzy relation inequality. Fuzzy Optim. Decis. Mak. 1–33 (2022).

Behzadipour, A., Gitinavard, H., & Akbarpour Shirazi, M. A novel hierarchical dynamic group decision-based fuzzy ranking approach to evaluate the green road construction suppliers. Scientia Iranica. (2022).

Rajabpour, E., Fathi, M. R., & Torabi, M. Analysis of factors affecting the implementation of green human resource management using a hybrid fuzzy AHP and type-2 fuzzy DEMATEL approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 1–16 (2022).

Saranya, T., & Saravanan, S. A comparative analysis of groundwater vulnerability models—fuzzy DRASTIC and fuzzy DRASTIC-L. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 1–15 (2021).

Gitinavard, H., Mousavi, S. M., & Vahdani, B. A balancing and ranking method based on hesitant fuzzy sets for solving decision-making problems under uncertainty. Int. J. Eng. Trans. B Appl. (2014).

Gitinavard, H., Mousavi, S. M., Vahdani, B. & Siadat, A. Project safety evaluation by a new soft computing approach-based last aggregation hesitant fuzzy complex proportional assessment in construction industry. Scientia Iranica 27(2), 983–1000 (2020).

Borujeni, M. P., Behzadipour, A. & Gitinavard, H. A dynamic intuitionistic fuzzy group decision analysis for sustainability risk assessment in surface mining operation projects. J. Sustain. Min. 24(1), 15–31 (2025).

Gitinavard, H. & Zarandi, M. H. F. A mixed expert evaluation system and dynamic interval-valued hesitant fuzzy selection approach. Int. J. Math. Comput. Phys. Electr. Comput. Eng. 10, 337–345 (2016).

Gitinavard, H., Ghaderi, H. & Pishvaee, M. S. Green supplier evaluation in manufacturing systems: A novel interval-valued hesitant fuzzy group outranking approach. Soft. Comput. 22, 6441–6460 (2018).

Zhang, W. R. Bipolar fuzzy sets and relations: a computational framework for cognitive modeling and multiagent decision analysis. In NAFIPS/IFIS/NASA’94. Proceedings of the First International Joint Conference of The North American Fuzzy Information Processing Society Biannual Conference. The Industrial Fuzzy Control and Intellige, 305–309 (IEEE, 1994).

Poulik, S. & Ghorai, G. Applications of graph’s complete degree with bipolar fuzzy information. Complex Intell. Syst. 8(2), 1115–1127 (2022).

Akram, M. Bipolar fuzzy graphs with applications. Knowl.-Based Syst. 39, 1–8 (2013).

Rajeshwari, M., Murugesan, R., Kaviyarasu, M. & Subrahmanyam, C. Bipolar fuzzy graph on certain topological indices. J. Algebr. Stat. 13(3), 2476–2481 (2022).

Lu, J., Zhu, L. & Gao, W. Cyclic connectivity index of bipolar fuzzy incidence graph. Open Chem. 20(1), 331–341 (2022).

Sarwar, M. & Akram, M. Novel concepts of bipolar fuzzy competition graphs. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 54(1), 511–547 (2017).

Singh, P. K. Bipolar fuzzy concepts reduction using granular-based weighted entropy. Soft Comput. 1–13. (2022).

Abughazalah, N., Muhiuddin, G., Elnair, M. E. & Mahboob, A. Bipolar fuzzy set theory applied to the certain ideals in BCI-algebras. Symmetry 14(4), 815 (2022).

Alghamdi, M. A., Muthana, N. M. & Alshehri, N. O. Novel Concepts of Bipolar Fuzzy BCK-Submodules (Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society, 2017).

Garai, T., Biswas, G., & Santra, U. A novel MCDM method based on possibility mean and its application to water resource management problem under bipolar fuzzy environment. In International Conference on Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems, 405–412 (Springer, 2022).

Zhao, M., Wei, G., Wei, C. & Guo, Y. CPT-TODIM method for bipolar fuzzy multi-attribute group decision making and its application to network security service provider selection. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 36(5), 1943–1969 (2021).

Alghamdi, M. A., Alshehri, N. O. & Akram, M. Multi-criteria decision-making methods in bipolar fuzzy environment. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 20(6), 2057–2064 (2018).

Akram, M. & Arshad, M. Bipolar fuzzy TOPSIS and bipolar fuzzy ELECTRE-I methods to diagnosis. Comput. Appl. Math. 39(1), 1–21 (2020).

Akram, M. & Al-Kenani, A. N. Multiple-attribute decision making ELECTRE II method under bipolar fuzzy model. Algorithms 12(11), 226 (2019).

Riaz, M., Pamucar, D., Habib, A., & Jamil, N. Innovative bipolar fuzzy sine trigonometric aggregation operators and SIR method for medical tourism supply chain. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022 (2022).

Jana, C., Pal, M. & Wang, J. Q. Bipolar fuzzy Dombi aggregation operators and its application in multiple-attribute decision-making process. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 10(9), 3533–3549 (2019).

Jana, C., Pal, M. & Wang, J. Q. Bipolar fuzzy Dombi prioritized aggregation operators in multiple attribute decision making. Soft. Comput. 24(5), 3631–3646 (2020).

Zararsız, Z. & Riaz, M. Bipolar fuzzy metric spaces with application. Comput. Appl. Math. 41(1), 1–19 (2022).

Jamil, N., & Riaz, M. Bipolar disorder diagnosis with cubic bipolar fuzzy information using TOPSIS and ELECTRE-I. Int. J. Biomath. 2250030 (2022).

Ramot, D., Milo, R., Friedman, M. & Kandel, A. Complex fuzzy sets. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 10(2), 171–186 (2002).

Tamir, D. E., Jin, L. & Kandel, A. A new interpretation of complex membership grade. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 26(4), 285–312 (2011).

Singh, P. K. Crisply generated complex fuzzy concepts analysis using shannon entropy. Neural Process. Lett. 1–25. (2022).

Hu, B., Wu, W. & Dai, S. Homogeneity of complex fuzzy operations. Axioms 11(6), 274 (2022).

Khan, M., Rehman, R. F. U., Anis, S., & Zeeshan, M. Denoising Data in Signal Processing under the Complex Fuzzy Environment. (2022).

Bi, L., Dai, S., Hu, B. & Li, S. Complex fuzzy arithmetic aggregation operators. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 36(3), 2765–2771 (2019).

Bi, L., Dai, S. & Hu, B. Complex fuzzy geometric aggregation operators. Symmetry 10(7), 251 (2018).

Mahmood, T. & Ur Rehman, U. A novel approach towards bipolar complex fuzzy sets and their applications in generalized similarity measures. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 37(1), 535–567 (2022).

Ur. Rehman, U. and Mahmood, T.,. The generalized dice similarity measures for bipolar complex fuzzy set and its applications to pattern recognition and medical diagnosis. Comput. Appl. Math. 41(6), 1–30 (2022).

Mahmood, T., Rehman, U. U., Ali, Z., Aslam, M. & Chinram, R. Identification and classification of aggregation operators using bipolar complex fuzzy settings and their application in decision support systems. Mathematics 10(10), 1726 (2022).

Rehman, U. U., Mahmood, T., Albaity, M., Hayat, K. & Ali, Z. Identification and prioritization of DevOps success factors using bipolar complex fuzzy setting with frank aggregation operators and analytical hierarchy process. IEEE Access 10, 74702–74721 (2022).

Mahmood, T., ur Rehman, U., Ali, Z. & Aslam, M. Bonferroni mean operators based on bipolar complex fuzzy setting and their applications in multi-attribute decision making. AIMS Math. 7(9), 17166–17197 (2022).

Mahmood, T. & Ur Rehman, U. A method to multi-attribute decision making technique based on Dombi aggregation operators under bipolar complex fuzzy information. Comput. Appl. Math. 41(1), 1–23 (2022).

Mahmood, T., Rehman, U. U., Ahmmad, J. & Santos-García, G. Bipolar complex fuzzy Hamacher aggregation operators and their applications in multi-attribute decision making. Mathematics 10(1), 23 (2021).

Mahmood, T., Rehman, U. U., Jaleel, A., Ahmmad, J. & Chinram, R. Bipolar complex fuzzy soft sets and their applications in decision-making. Mathematics 10(7), 1048 (2022).

Kumar, A., Singh, A. K. & Garg, A. Evaluation of machine learning techniques for heart disease prediction using multi-criteria decision making. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 46(1), 1259–1273 (2024).

Freitas, P., Antunes, C. H., & Dias, J. A multi-criteria sorting approach for diagnosing mental disabilities. In International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems, vol. 2, 392–398 (SCITEPRESS, 2012).

Lin, Y. C. et al. Disability prediction in ageing population based on disease status: machine learning approaches. In ISEE Conference Abstracts, vol. 2023, no. 1 (2023).

Kumar, A., Singh, R., & Kumar, S. Application of multi-criteria decision-making in health care towards various disease prediction. In 2024 4th International Conference on Innovative Practices in Technology and Management (ICIPTM), 1–5 (IEEE, 2024).

Zadeh, L. A. The concept of a linguistic variable and its application to approximate reasoning—I. Inf. Sci. 8(3), 199–249 (1975).

Peng, D., Wang, J., Liu, D., & Cheng, Y. The interactive fuzzy linguistic term set and its application in multi-attribute decision making. Artif. Intell. Med. 102345. (2022).

Wang, X. F., Wang, J. Q. & Yang, W. E. Multi-criteria group decision making method based on intuitionistic linguistic aggregation operators. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 26(1), 115–125 (2014).

Ju, Y., Liu, X. & Ju, D. Some new intuitionistic linguistic aggregation operators based on Maclaurin symmetric mean and their applications to multiple attribute group decision making. Soft. Comput. 20(11), 4521–4548 (2016).

Erol, I., Ar, I. M., Peker, I. & Searcy, C. Alleviating the impact of the Barriers to circular economy adoption through blockchain: An investigation using an integrated MCDM-based QFD with hesitant fuzzy linguistic term sets. Comput. Ind. Eng. 165, 107962 (2022).

Gao, H., Wu, J., Wei, C. & Wei, G. MADM method with interval-valued bipolar uncertain linguistic information for evaluating the computer network security. IEEE Access 7, 151506–151524 (2019).

Qin, J. & Liu, X. An approach to intuitionistic fuzzy multiple attribute decision making based on Maclaurin symmetric mean operators. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 27(5), 2177–2190 (2014).

Wei, G. & Lu, M. Pythagorean fuzzy Maclaurin symmetric mean operators in multiple attribute decision making. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 33(5), 1043–1070 (2018).

Smarandache, F. A unifying field in logics: neutrosophic logic. In Philosophy, 1–141 (American Research Press, 1999).

Ali, M. & Smarandache, F. Complex neutrosophic set. Neural Comput. Appl. 28, 1817–1834 (2017).

Broumi, S. Secure dominance in neutrosophic graphs. Neutrosophic Sets Syst. 56(1), 7 (2023).

Mahmood, T., Rehman, U. U. & Naeem, M. Prioritization of strategies of digital transformation of supply chain employing bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic aggregation operators. IEEE Access 11, 3402–3415 (2023).

Fang, H., ur Rehman, U. & Mahmood, T. Identification of eco-friendly transportation mode by employing complex intuitionistic fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making approach based on probability aggregation operators. IEEE Access. (2024).

Albaity, M., ur Rehman, U. & Mahmood, T. Data source selection for integration in data sciences via complex hesitant fuzzy rough multi-attribute decision-making method. IEEE Access 12, 110146–110159 (2024).

Zheng, L., Mahmood, T., Ahmmad, J., Rehman, U. U. & Zeng, S. Spherical fuzzy soft rough average aggregation operators and their applications to multi-criteria decision making. IEEE Access 10, 27832–27852 (2022).

Ur Rehman, U., Mahmood, T., Ali, Z. & Panityakul, T. A novel approach of complex dual hesitant fuzzy sets and their applications in pattern recognition and medical diagnosis. J. Math. 2021(1), 6611782 (2021).

Broumi, S. & Witczak, T. Heptapartitioned neutrosophic soft set. Int. J. Neutrosophic Sci. 18(4), 270–290 (2022).

Zhang, H. Y., Wang, J. Q. & Chen, X. H. Interval neutrosophic sets and their application in multicriteria decision making problems. Sci. World J. 2014(1), 645953 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the King Salman center for Disability Research for funding this work through Research Group no KSRG-2024-065.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contribute equal.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics declaration statement

The authors state that this is their original work, and it has not been submitted to or under consideration in any other journal simultaneously.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rehman, U., Khan, M.A., Al-Dayel, I. et al. Selection of AI model for predicting disability diseases through bipolar complex fuzzy linguistic multi-attribute decision-making technique based on operators. Sci Rep 15, 19195 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01909-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01909-z