Abstract

There is a consensus on the role of protein conformational changes within the photosynthetic antenna that alter the spectral properties of the embedded pigments during regulated heat dissipation, but despite this, the molecular mechanisms involved are still poorly understood. The mechanisms, associated with the quenching of excessive energy, are however commonly seen in vitro as ‘red spectral forms’ of Chlorophyll a or red-shifted and broadened absorbance behaviour. Similar mechanisms are expected to occur in vivo, but so far, the spectral absorbance changes have not been described in detail at the whole plant canopy level. Here we derive the dynamic changes in surface absorbance features from canopy reflectance of tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum L.), under increasing light exposure and drought. Specific features in the green (520 nm-peak) and the red-edge (695 nm-peak) region could indicate the quick activation of quenched conformational states under low light conditions, for all plant canopies. Under additional drought stress, further red-shifted and broadened absorbance changes appear, suggesting another conformational change. The latter changes disappeared upon drought recovery. Observing these antenna-related mechanisms from proximal sensing demonstrates the promising potential of imaging spectroscopy to detect the stepwise tuning of regulated energy dissipation of plants in a non-destructive way.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Light is essential for plant photosynthesis, but managing between too little and too much energy for absorption, requires a sophisticated system with multiple levels of regulation and repair1. The regulation of the photon capture happens in the photosynthetic antenna system which are engineered for the absorption of photons and immediate transfer of energy in the form of excited states or excitons to the photosynthetic reaction centers (RC). An excessive amount of photons, which is defined by the environmental conditions to which the plant is adapted/exposed2, can trigger photooxidative and possibly damaging processes3, ranging from production of reactive oxygen species, damage in the repair system, suppression of photosynthesis (photoinhibition)4 and even cell death5. Under normal conditions, the occurrence of these damages is relatively minor as plants have developed several responses to mitigate its effects and thereby modify its internal regulation from quick and short-term to long-term mechanisms.

A large number of mechanisms fall under the photoprotection of plants, considering all processes that prevent or decrease photoinhibition in the antenna6. The most important short-term reversible photoprotective process in higher plants, eukaryotic algae, and essentially all other oxygenic photosynthetic organisms, is the so-called non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) of chlorophyll fluorescence6. Many reviews have been published on the complex regulation of NPQ, which involves several mechanisms, intended to be separated by different quenching components3. The most dominant component, qE, is assigned to a synergistic action of the lumen acidification, the activation of the pH sensor PsbS, and the change in the xanthophyll pigment pool composition3. Despite their low abundance among pigments, xanthophylls play an important role in the activation of the energy dissipation mechanisms7. Eventually, the excessive excitation energy is safely dissipated into heat. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying these changes are not well understood, as several interrelated processes occur on a short timescale (from picoseconds to minutes) in the thylakoid membrane involving both chemical and structural changes in the antenna, i.e. the latter referring to the dissociation of supercomplexes in the antenna8. The chemical changes, on the other hand, are described by the xanthophyll conversions, referring to both the Violaxanthin-Antheraxanthin-Zeaxanthin (VAZ) cycle9 and the Lutein-epoxy-Lutein (LxL) cycle10,11. In vitro studies on LHCII complexes and thylakoid membranes have revealed the distinct behavior between unquenched and quenched states, reflecting light-harvesting processes expected to occur in vivo. For example, considerable excitation energy dissipation can be observed on purified LHCII complexes, indicating red emitting states in the quenched states12,13,14,15. Ruban and co-workers16 associated these red emitting states to the appearance of chlorophyll species absorbing at longer wavelengths, being linked with an aggregated state of the LHCII. The molecular mechanisms behind regulated heat dissipation are however still debated, with conflicting models involving different energy transfer processes between Chl and Car or Chl and Chl3. Although in vitro spectroscopy is advancing the understanding of NPQ mechanisms, its physiological relevance when extrapolating the spectral analysis to intact plant systems with the aim for non-invasive remote stress detection remains somewhat underexplored.

Already in the 80 s, in vivo antenna adjustments through the non-radiative de-excitation processes were studied through photoacoustic spectroscopy, which could witness a change in action spectra of different photobiological processes17,18. More recently, specific in vivo absorption changes resulting from early-stress antenna adjustments to excessive energy have been studied under carefully designed spectroscopy set-ups, able to monitor slow conformational changes in the antenna19. As a complication to spectroscopic analysis at the level of the intact leaf, absorption changes have been often observed in parallel with additional scattering changes related to chloroplast movement20,21,22,23, making it difficult to disentangle light avoidance from regulated heat dissipation processes. Careful spectral analysis may however allow the separation of the different processes. Chloroplast movements in response to high light reduce total absorbance amplitude, while non-radiative de-excitation processes are expected to lead either (1) to an increase in absorbance in the green range or (2) to an red-shifted and broadened absorption in the chlorophyll red peak region19.

The red-edge region, marking the edge of chlorophyll’s red absorption tail in the 680–750 nm range, is a key transition in the reflectance spectrum of plants. In remote sensing, changes in the red edge have been commonly ascribed to the dominant effect of changes in the chlorophyll concentration24,25, typically through spectral indices26,27,28. Through the first derivative analysis of the red-edge shape variable shape behavior has been argued to be due a change in Chl content alone29, or additionally thought to be due to the variable chlorophyll fluorescence emission occurring in the same region30. The latter effect is however expected to be minor and spectrally different compared to the variable and dominant absorbance behaviour of chlorophyll. Older work31 also suggested the influence of “red spectral forms of Chlorophyll a” on the overall red edge, but no clear in vivo mechanism causing this effect has been described so far. From isolated LHC32,33 or intact chloroplasts16,33 molecular mechanisms responsible for quenching excessive energy are seen as ‘red spectral forms’ of Chlorophyll a or red-shifted and broadened absorbance behavior, which are also seen in vivo at leaf level19. Changes in red-edge absorbance (i.e. red-edge broadening) have been examined in relation to stress34,35, although the mechanism has not been described at high spectral resolution, resolving potential broadening and shifts in the antenna behaviour. The reason for this could be due to often simultaneous and more dominant spectral effects driven by biochemical changes (i.e., pigment loss) and variability in the canopy structure (i.e., biomass), with additional illumination-target-sensor geometry effects. We hypothesize that such red-shifted absorbance mechanism(s) should however be possible to spectrally isolate under a controlled canopy spectroscopy set-ups with constant illumination-target-sensor geometry, considering the spatial representativity of the canopy structure.

The spectral region which has been more commonly used to monitor changes in the light use efficiency behavior of plants, is the so-called PRI-region (500–600 nm), referring to the two band-based photochemical reflectance index (PRI) calculated in this region36,37. The changes in PRI are related to the quick qE regulated-heat dissipation component in the short-term38, but are also affected by long-term changes in the pigment pools due to spectral overlap with the chlorophylls39,40. Hence, several specific mechanisms are expected to alter the dynamic absorbance in the green and red region.

Understanding how stress affects antenna-related absorbance mechanisms at the canopy level could unlock significant potential for the early stress detection by imaging spectroscopy sensors. With the aim to better understand how controlled heat dissipation affects the top-of-canopy plant reflectance signal under normal and excessive light conditions, we designed an experiment to track the top-of-canopy reflectance and its dynamics along progressively quenched states at the whole plant level. A combination of active fluorescence imaging and imaging spectroscopy was used to study the nature of the in vivo mechanisms related to the regulated heat dissipation and the potential pigments involved at whole plant level.

Materials and methods

Plant screening chamber and experimental set-up

The present work used tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L. cv Moneymaker) plants as study subject. Specifically, 40 seedlings were cultivated in a growth chamber with a photoperiod of 16-h light (PAR = 300 µmol m−2 s−1) and 8-h darkness. Four weeks after germination the plants were transplanted to pots with coconut fiber substrate and placed inside the climate chamber with plant screening equipment (FytoScope + PlantScreen™ Transect System, Photon Systems Instruments, Drásov, Czech Republic). The photoperiod was maintained as previously, with a temperature cycle of 19/22 °C (night/day) and a humidity level of 55%. Plants were irrigated every 2–3 days with half-strength Hoagland nº2 solution. After one week of adaptation to these conditions the plant screening experiment began. The PlantScreen™ Transect System consists of a XY movable multisensory system, designed for automated, non-destructive measurement and image analysis of plants in a high-throughput manner. It contains a top-view chlorophyll fluorescence imaging unit, a top-view RGB camera, a 3D scanning and thermal imaging unit, and a top-view VNIR hyperspectral camera for imaging spectroscopy (Fig. 1a).

Experimental set-up of the plant screening experiment. Panel (a) shows the climate-controlled chamber with the plant trays (water deficit and control treatments) under the XY movable plant screening system with two imaging systems (1: PAM fluorescence unit, 2: VNIR hyperspectral unit). Panel (b) shows the watering schedule and sampling days for leaf spectroscopy and pigment analysis during the treatment (red) and recovery (green) phase. Panel (c) shows the daily protocols and data analysis of the two imaging systems, scanning the plant trays under steady-state conditions after 8 h darkness and 20 min after each light acclimation (PAR100, PAR300, PAR500, etc.). Data analysis for selected illumination conditions (in bold) involved the minimal and maximal active fluorescence signal (Fo, Fm) and derived quantum yield (QY) for the PAM fluorescence imaging, and the canopy reflectance (Rdark, R300, etc.), based on canopy radiance, white reference (WR) and dark current (DC) measurements, for the VNIR hyperspectral imaging. True surface absorbance was estimated for each PAR (Adark, A300, etc.), together with the stepwise and cumulative differences (ΔA) between the sequential PAR levels.

The potted seedlings were distributed homogeneously into four plant trays (10 seedlings per tray), designed for the plant screening system. Trays were divided into a “control” and “water deficit” treatment and the four plant trays were screened for 16 consecutive days. For the drought treatment, water irrigation was discontinued from day 0 (D0) until day 7 (D7) and was reinitiated on day 8 (D8) marking the beginning of the recovery phase (from D8 to D15) (Fig. 1b). The length of the drought treatment and the overall design of the experiment was based on a previous experiment with the same variety41, indicating drought stress responses within a couple of days.

Growing light conditions were supplied by two large controllable LED fyto-panels (cool white 6500 K + deep-red 660 nm + far-red 735 nm), positioned under a 70° angle along each side of the plant trays (Fig. 1a). This set-up allowed a homogeneous irradiance field at canopy top height (verified by a PAR sensor), while permitting top-view sensor movement. At the start of each photoperiod, plants underwent sequential exposure to incremental light levels for 30-min intervals using PAR levels of 100, 300, 500, 700, 900, 1100 and 1500 µmol m−2 s−1. Far-red light remained fixed at 34 µmol m−2 s−1, while cool white light was adjusted according to each PAR level. At darkness and steady-state conditions of PAR300, PAR700, PAR1100 and PAR1500, the plant screening system was set for automated scanning of the entire transect using sequentially the chlorophyll fluorescence imaging unit and the VNIR hyperspectral camera (Fig. 1c).

PAM-based fluorescence imaging

A FluorCam FC-800MF Pulse Amplitude Modulated (PAM) system with RGB camera (Photon Systems Instruments, Drásov, Czech Republic) was operated to provide a field-of-view (FOV) image area of 435 × 320 mm for each tray. To track the quenching state between treatments, a daily protocol to measure the dark-state PSII activity (Fv/Fm, here referred to as maximum quantum yield or QYmax) and steady-state PSII quantum yield at each PAR level (here referred to as QY300, QY700, etc.) was automated. This protocol applies pulse-modulated short flashes (0.02 µmol m−2 in 10-μs pulses) for the measurement of the minimum fluorescence (Fo or Foʹ), followed by a saturating light pulse (5296 µmol m−2 s−1) for the measurement of the maximum fluorescence (Fm or Fmʹ). QY is calculated as Fv/Fm or Fvʹ/Fmʹ with Fv = Fm − Fo). Dark-adapted fluorescence measurements were taken before the start of the photoperiod, and light-adapted measurements were taken 20 min after every light acclimation (Fig. 1c). Fluorescence parameters were extracted for all plant-classified pixels which were determined by the plant mask generated through the overlay of the RGB and FluorCam images. Image processing was further achieved by considering each tray as a unit of study, thereby negating the effect of plant movement or plant extraction for destructive (pigment) analyses (see further). Along the experiment the plant-classified pixels ranged from 16,357 (during water deficit phase) to 313,638 pixels. Statistical tests were performed with SPSS software (version 28.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) analysing the statistical differences in Foʹ, Fmʹ and QY over time and between treatment groups for each PAR condition. Initially, the normality of the data distribution was examined. For normally distributed data, Student’s t-test was employed to compare treatments, while for time series analysis, ANOVA (Duncan or Welch’s) was applied. In cases where the data was not normally distributed, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied.

Imaging spectroscopy

The spectroscopy imaging unit comprises a HySpec VNIR camera (Photon Systems Instruments, Drásov, Czech Republic), which is a push-broom hyperspectral line-scanner that measures the spectral range of 380–900 nm (VNIR) with a spectral resolution of ~ 0.8 nm (FWHM). The CMOS sensor has a depth of 12 bits, with a lens with a focal length of 6 mm, generating a scanning area of 380 × 310 mm. The resulting pixel size at the operated height is 0.8 mm2. The measurement protocol for canopy reflectance measurements consists of a dark current acquisition, performed by averaging five scanning lines in complete dark conditions. Next, a 600 W halogen tube light source is switched on for the white calibration measurement, using an average of five scanning lines of a white reference panel. Then, the transect is further automatically scanned to obtain the top of canopy reflected radiance. The reflectance (R) image of each tray is calculated as the quotient of the reflected radiance image and the white reference acquisition, both being previously subtracted by the dark current signal (see Supplementary Fig. S1 for a pixel-based example). Non-vegetated pixels were masked using a thresholding method based on a customized vegetation index, thus avoiding heterogenous fractional cover effects. For the reflectance and derived surface absorbance estimation we used Python version 3.11 (Python Software Foundation, Beaverton, OR, USA) with python modules Numpy v. 1.24 and Pandas v. 2.0. As previously described, hyperspectral images were taken for plants under steady-state conditions, after a 30-min period of adaptation to respectively dark conditions (Rdark), 300 (R300), 700 (R700), 1100 (R1100) and 1500 (R1500) µmol m−2 s−1 (Fig. 1c). The average canopy reflectance (± s.e.) for each treatment and each PAR acclimation was derived by calculating the mean of the reflectance values obtained from 20 automated square areas within the two trays, with a total of 40 areas per treatment. Next, surface absorbance (A(λ) was calculated assuming a dark soil (soil brightness assumed zero) using the energy conservation equation42 A = 1 − R − T. Further we assumed R = T, supported by the similarity between the canopy and leaf reflectance (Fig. S3) on the one hand and the leaf reflectance and transmittance on the other hand (Fig. S8). While these assumptions do not hold universally, they provide a practical and computationally efficient approach in scenarios such as this, where scattering effects (both within the foliage and from the background) are minimal. The derived absorbance is lowered by its A(λ) minimum value (typically a wavelength beyond 800 nm), setting the baseline for all absorbance estimations to 0. Further, the signal was normalized by the highest A(λ) factor (typically located at a blue wavelength), providing all estimated absorbance in the absolute range [0,1]. This was done for each light acclimation recording, providing respectively Adark, A300, A700, A1100 and A1500, and allowing further comparison of the PAR driven changes in the surface-derived absorbance. With these adjustments the multiple scattering effects, enhancing the absorptions, were empirically minimized, assuming mainly pigment absorbance effects. It is further shown that the spatial variability in the multilayer scattering could be accounted for by the spatial sampling, reducing the large scattering differences observed in the far-red (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Optical changes in the vegetation surface due to photoprotection mechanisms were investigated through the estimated absorbance difference (ΔA) between the light-acclimated (“quenched”) conditions and the dark-adapted (“unquenched”) condition for each day. Spectral differences were calculated in a cumulative as well as in a stepwise manner using the estimated absorbance of the sequential PAR levels (Fig. 1c). The error in ΔA was propagated from the standard error obtained from the images, which also represent the spatial variability due to the multilayer scattering differences within the canopy. Hence, it should be taken into consideration that the presented standard “error” accounts also for the spatial variability due to biological and multi-layer scattering variability. This variability causes a higher dispersion in the reflectance shape compared to the instrumental noise (see an example in Supplementary Fig. S2), wherefore it is the main propagated error observed in the ΔR or ΔA at image level. It should be, however, pointed out that the shape of this scattering variability is different than the one of the obtained ΔR or ΔA signals, and that this effect is largely averaged out (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Changes in the observed difference peaks were also tracked from the canopy reflectance and its first derivative (Rʹ), demonstrating the observations for the canopy R signal commonly obtained through remote sensing. The spectrum was divided into three ranges, from 500–570 nm, 650–710 nm and 710–900 nm. For each spectral range, the minimum value was extracted from the stepwise ΔR, obtaining the peak position. To differentiate between genuine absorbance shifts resulting from the intrinsic absorbance behavior in the photosynthetic antenna and other scattering influences, a first derivative analysis was conducted on the dark-adapted reflectance (Rdark) each day throughout the experiment. The first derivative calculation used the gradient of second-order accurate central differences. Furthermore, to ensure the reliability of the canopy reflectance observations regarding potential impact of structural or plant cover effects, an additional test was conducted in which plant cover was altered by removing well-watered plants (from 5 to 1) within a time frame of minutes, without altering other variables (light, temperature, watering) that could influence the functional state of the plant. This test was to guarantee that the reflectance comparison between days was still meaningful even when the number of plants (or pixels) examined was considerably decreased.

Leaf spectroscopy and pigment analyses

Bi-directional leaf level spectroscopy measurements were collected for plants adapted to two PAR levels (PAR300: growing light conditions and PAR1000: intensive light) on D1, D3, D7, D15 to estimate the leaf optical properties. For each treatment six leaves were sampled. Two QEPro spectroradiometers (Ocean Optics, Dunedin, FL, USA) were used, both connected to a FluoWat leaf clip19,43,44 with two fiber optics (upward channel and downward channel, each with a FOV of 25°). Simultaneous measurements of upward and downward leaf radiance (Lup(λ), Ldw(λ), W m−2 sr−1 nm−1) were taken, respectively from the perpendicular directions to the adaxial and abaxial leaf surface. The light source setup for maintaining the leaves at the PAR levels was provided by a high-voltage LED with a spectral range covering from 400 to 780 nm (High Cri LED 10 W 17 V 3050–5900 K, Yuji International Co., Ltd, China) (for further details see19).

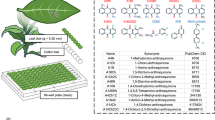

Additionally, pigments (chlorophylls and carotenoids) were extracted from immediately frozen leaf discs (1 cm2 Ø) collected from two plants acclimated to 300 μmol m−2 s−1 and 1100 μmol m−2 s−1. For each treatment, light condition and sampling day, two discs were sampled from six different leaves. The pigment extraction was performed twice using 250 μl of pure acetone buffered with CaCO3, and after centrifugation, the supernatant was filtered through a 0.45 μm polytetrafluoroethylene filter (Teknokroma, Barcelona, Spain). The pigment extracts were characterized and quantified by high performance liquid chromatography system (Waters ACQ Arc SysCore HPLC) equipped with a diode array detector (DAD 2998, Waters) set to scan from 300 to 700 nm, and the Empower3 software (Waters®, Barcelona, Spain). A C30 carotenoid column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) (YMC Europe GMBH, Germany) coupled to a C18 guard column (10 × 4.3 mm, 5 μm) (Teknokroma, Barcelona, Spain) were used with a ternary gradient MeOH, water and methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE). The initial gradient elution composition consisted of 90% MeOH, 5% water and 5% MTBE. The solvent composition changed linearly to 95% MeOH and 5% MTBE at 12 min. During the next 8 min the solvent composition was changed to 86% MeOH and 14%MTBE. After reaching this concentration the solvent was gradually changed to 75% MeOH and 25% MTBE at 30 min. Final composition was reached at 45 min and consisted of 55% MeOH and 45% MTBE. Initial conditions were re-established in 2 min and re-equilibrated for 20 min before the next injection. The flow rate was 1 ml/min, column temperature was set to 25 °C, and injection volume was 20 μl. Each pigment was identified by absorbance spectra and retention time. For each elution, a Maxplot chromatogram was obtained which integrated each pigment peak at its corresponding maximum absorbance wavelength and their contents were calculated using the appropriate calibration curves, as described for xanthophylls in previous studies45,46, and the calibration curves of chlorophylls a and b were performed using the corresponding analytical standards (Sigma-Aldrich, USA).

Results

Canopy-observed antenna regulation during diurnal light-induced quenching

Overall, both control and treatment plants showed subtle changes in the steady-state canopy reflectance and derived surface absorbance along increased PAR levels during the entire experiment (Supplementary Figs. S3, S4). Figure 2 shows an example of the control plants’ photochemical quenching along the illumination schedule, demonstrating a gradual QY decrease from an average of 0.84 ± 0.03 (dark-adapted, unquenched) to an average of 0.61 ± 0.09 (1500 µmol m−2 s−1, maximally quenched) (Fig. 2a–e). High spectral resolution seen from the canopy R signal (Fig. 2f) allowed the calculation of the stepwise ΔR changes along the illumination changes which are shown for illustrative reasons (Fig. 2g–j). In parallel the estimated surface absorbance (Fig. 2k) and the corresponding stepwise ΔA changes are shown (Fig. 2l–o). The relatively high propagated standard error shown represents the spatial heterogeneity due to biological variability and multilayer scattering effects, rather than the measurement “error” (see Supplementary Fig. S2). Cumulative and stepwise surface absorbance changes of both treatments along the full experiment are shown in the Supplementary Fig. S5. Overall, cumulative ΔA features showed a notable similarity across the diurnal progressive quenching for the control plants. Conversely, the stepwise ΔA features were able to track more distinctive spectral patterns along the progressive quenching states. The stepwise changes observed in surface absorbance are in the order of a few percent, with peaks up to 4% in the red-edge spectral range (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Photochemical quenching sequentially observed by the fluorescence imaging unit and the hyperspectral camera for a tray with control plants at day 2 of the experiment. Panels (a–e) shows the steady-state PSII quantum yield (QY) along the PAR acclimation (dark, 300, 700, 1100 and 1500 µmol m−2 s−1, respectively), together with the mean ± s.d. for all plant pixels (Npixels). Panel (f) shows the steady-state top-of-canopy reflectance along the PAR acclimation (R, mean ± s.e., n = 20 plant areas within each tray) and panels (g–j) show the stepwise change in canopy reflectance (ΔR, mean ± s.e.) between the different PAR acclimation steps. Panel (k) shows the estimated surface absorbance along the PAR acclimation (A, mean ± s.e., n = 20 plant areas within each tray) and panels (l–o) show the stepwise change in surface absorbance (ΔA, mean ± s.e.) between the different PAR acclimation steps The cumulative changes between each PAR level and the dark are shown in both R (panel p) and A (panel q). The Chl a Q-band region from 570 to 750 nm is highlighted in yellow. Fixed vertical lines at 520 nm (green) and 695 nm (red) mark the two main peak features for all ΔR and ΔA.

During fast quenching, induced by PAR300, stepwise ΔA (i.e., A300-Adark) calculations demonstrate the distinctive lowest-energy excited state (Q band) of Chl, i.e. a prominent 695-nm ΔA peak in the red-edge region together with the three higher vibrational peaks (Figs. 2g, S3), indicating a ΔA shift in the Chl excited state absorption behavior. The red ΔA shift remains present during more advanced quenched states and only progresses to a minor extent while QY gradually decreases (Fig. 2p,q). Simultaneously, a ΔA peak around 520 nm emerges (Xan region), exhibiting characteristics distinct from those of Chl in its excited state. This peak shows additional increases along further progressive quenching at PAR700 (A700-A300) and further at PAR1100 (A1100-A700) (Fig. 2l–o), with diminished Chl Q-band features. This points to a separate mechanism in the Xan spectral region, not necessarily occurring synchronized with the Chl-related absorption changes. The latter changes therefore do not seem to be directly involved in the dynamic quenching behaviour. Also, a subtle peak shift was observed in the 520–540 nm peak range for the control plants, and it occurred throughout the full experiment (Supplementary Fig. S5). The PRI, typically calculated in remote sensing studies tracking the reflectance decrease around 520–540 nm, on the other hand, is also demonstrating a PAR-driven progressive decrease for both treatments (Supplementary Fig. S7), which supports the observed cumulating absorbance increases in this region (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Canopy-observed antenna regulation under additional drought stress

Active fluorescence measurements could indicate the enhancement in quenching under drought. Statistical differences between control and water-deficit plants were found for the Foʹ (Fig. 3a), Fmʹ (Fig. 3b) and QY (Fig. 3c) parameters, during both the water deprivation phase (D0-D7) and the recovery phase (D8-D15). On D7, water deficit plants showed a significantly lower QY compared to control plants, both at PAR300 (p < 0.001) and PAR1500 (p = 0.017) levels. Both Foʹ and Fmʹ were found significantly lower (p < 0.001) as well on D7. Upon early recovery (D8), all three parameters were still significantly lower (p < 0.01 or p < 0.001, see Supplementary Table S1) compared to the control values, but a strong increase in photon harvesting activity was observed the following days. Eventually, higher canopy QY values were observed for the recovered water deficit plants on D12 and D15, due to recovered Foʹ values and significantly higher Fmʹ values.

Mean active fluorescence parameters from the fluorescence imaging canopy system, for selected days of the stress phase (D2, D4, D7) and the recovery phase (D8, D12, D15). Steady-state minimum fluorescence (Foʹ(-) with arbitrary units, panel (a), maximum fluorescence in steady-state (Fmʹ (-), panel (b) and steady-state PSII quantum yield (QY (-) dimensionless, panel (c) are shown for control and water deficit plants (n = 14, 16 or 18, mean ± standard deviation). The significance level between treatments is given as: p-value < 0.05 (*), p-value < 0.01 (**); p-value < 0.001 (***).

At the start of the experiment, PAR-driven changes in the estimated surface absorbance showed similar ΔA features between treatments (Fig. 4a). Changes in ΔA were overall most pronounced during the early low light exposure (300 µmol m−2 s−1). For example, on D0, the ΔA spectra showed similar maxima in the 500–650 nm (Xan) region and in the red-edge region. Both treatments showed a distinct 520 nm peak, combined with the second red-edge shift as shown previously (Fig. 2). Towards the end of the stress phase (D5-D7) the canopy reflectance and estimated surface absorbance of water-deficit plants strongly altered, demonstrating an absorbance shift with lower absorbance in the red and higher absorbance in the far-red for the water deficit plants, shown by the A1500-A1000 feature (Figs. 4b, S3). Both the peaks in the green and in the far-red appear red-shifted and broadened compared to the quick changes. Eventually, at D7, canopy R of water deficit plants showed a strongly altered reflectance indicating the influence of a pronounced, red-shifted absorbance (Supplementary Fig. S2). On the first day of recovery (D8) ΔA still showed shifted and broadened maxima but amplitudes were lower and fluctuated in sign along the PAR transitions, as can be seen in the A700-A300 and A1100-A700 features (Fig. 4c). At final recovery (D14), estimated surface absorbance between treatments were again similar, showing less fluctuating behavior (Fig. 4d). Also, major ΔA changes were again centered around 520 nm and 695 nm and only minor peak shifting or broadening could be distinguished.

Estimated surface absorbance (A) and stepwise absorbance changes (ΔA) obtained along the different experimental phases: at the start (D0, panel (a), the end of early stress (D7, panel (b), the beginning of the recovery (D8, panel (c), and the final recovery phase (D14, panel (d). First column is normalized surface absorbance (mean ± s.e., n = 40 plant areas) at steady-state for each light acclimation (Adark, A300, A700, A1100 and A1500. The second and third columns are the stepwise change in estimated surface absorbance (mean, n = 40 plant areas) for the control and water deficit treatment, respectively. Fixed vertical lines at 520 nm, 540 nm, 560 nm and 695 nm mark important peak features for all ΔA.

The effect of the daily gradual absorbance shifts taking place (Supplementary Fig. S5) modifying the true absorbance properties is also qualitatively shown through the first derivative analysis of the dark-adapted canopy reflectance (Fig. 5). The derivative analysis shows an amplitude change in the first days, followed by a small change in shape along the stress phase, especially in the red-edge region, indicating a true absorbance shift. The canopy reflectance derivative analysis further confirmed the shape similarity between the treatments upon recovery, indicating the observed shifts being reversible.

First derivative analysis on the dark-adapted canopy reflectance of each treatment (Control and Water deficit). The first reflectance derivative (Rʹ, mean of n = 40 plant areas per treatment) is shown for each day along the experiment (D0-D15). Area differences between spectra are shaded highlighting the shape changes during early stress (D5-D7) and early recovery (D8-D11). The wavelength position of the maximum red-edge Rʹ are marked in each subplot.

Along the experiment, plant cover and density changed due to plant removal for destructive pigment analyses and drought effects. We could however rule out the effect of total plant cover on the true changes in the reflectance shape through an additional experiment (Fig. 6), where we demonstrated that there were no changes in the reflectance first derivative of healthy plants due to a lowered plant cover and density (Fig. 6a–c). Hence, Rʹ remained constant along the steps of plant removal (Fig. 6a). In contrast, along the stress experiment (Fig. 6d–g) Rʹ showed a noticeable change in the whole 500–750 nm range, and especially in the red-edge range (Fig. 6g).

Comparative analysis of canopy reflectance (R) and its first derivative (Rʹ) for changing canopy cover conditions of healthy plants versus stressed plants. For the control setup, VNIR screening under dark-adapted conditions images along the steps (panel a), dark-adapted canopy reflectance (Rdark) (panel b), and its first derivative (Rʹ) (panel c) are shown according to the number of pixels analyzed of each step (mean, n = 20 plant areas). For the water deficit setup, the temporal evolution of the quantum yield (QY) results is shown by tray images (panel d) and by its mean (± standard deviation, n = amount of pixels in y-axis) (panel e). The evolution of the VNIR spectral characteristics over time is shown for R (panel f) and Rʹ (panel g).

The subtle ΔA changes between quenched states of treatments were more difficult to track within single leaf measurements (Supplementary Fig. S6), on the one hand due to limited number of samples, and on the other hand due to the biological variability and used sampling strategy. Still, there are some key aspects that can be pointed out. Leaves from water deficit plants that underwent early stress also exhibited a higher standard error, which was consistent with the canopy-scale spectral response. Also, leaf absorbance was higher in the 500–650 nm range for leaves exposed to higher PAR, demonstrating in several cases a similar peak around 520 nm.

Two-step antenna regulations under stress

Based on the previous results, it shows that several adaptation mechanisms in the antenna alter the location of absorption maxima and shape across the 500–900 nm range (Supplementary Fig. S6). The first mechanism at the early induced quenching stage (PAR300) shows a consistent (narrow) red-shifted Chl 695-nm absorption peak in the Chl Q-band region, clearly affecting all the vibronic substructures (Fig. 7b). An absorbance increases around 520 nm also occurs at this stage, for both treatments, although not necessarily in parallel (Fig. 2). Across the treatments and days, the changes generated by this early adaptation mechanism are generally consistent and of similar magnitude. A second mechanism indicates a stronger broadening effect across both the green and the far-red range (Fig. 7c). The widened absorbance appears respectively around 560 nm and beyond 700 nm. These features appeared most clearly (1) in the water deficit treatment during final stress days, and (2) under strong excessive light.

Quick and slow top-of-canopy-observed antenna regulations, in both control and water deficit tomato plants. Panel (a) shows the illumination scheme, highlighting the illumination steps where distinct examples of antenna modifications were observed. Panel (b) and (c) are examples of respectively the quick and slow absorbance changes (ΔA) derived from the estimated surface absorbance during the dark-to-PAR300 acclimation (quick), and the PAR1100-to-PAR1500 acclimation (slow). On the right axis an unquenched absorbance spectrum (from Rdark on Day 1, in green) is shown as a reference to illustrate the red-shifted and broadened absorbance mechanisms with respect to the absorbance minimum at 674 nm. Red arrows in panel b indicate the shifted B-band of Chl, and black arrows in panel c indicate the broadening effects in the far-red.

Xanthophyll pool dynamics during stress and recovery

While total area-based pigment pools decreased under the drought treatment (Supplementary Table S2), relative pool sizes were able to illustrate the antenna stoichiometric plasticity to both water deficiency and excessive light (Fig. 8, Supplementary Table S3). Unfortunately, pigments of water deficit plants on D7 could not be analyzed, impeding a full analysis at the last day of stress treatment. Still, significantly larger Lut/Chl a (p < 0.01, at PAR300 and PAR1100) and Neo/Chl a (PAR1100: p < 0.001) pools were observed for the water deficit treatment in the early stages of the stress phase compared to the control plants (Fig. 8). Ant/Chl a pools also increased (PAR300: p < 0.05) for the water deficit plants during early stress, while Zea/Chl a did not. Chl a/Chl b pool ratio also decreased (PAR1000: p < 0.001) on D3 between control and stressed plants. Interestingly, at final recovery (D15), earlier water-deprived plants showed lower Lut/Chl a (PAR300: p = 0.002, PAR1100: p = 0.073), Neo/Chl a (PAR300: p < 0.001, PAR1100: p = 0.394) and Ant/Chl a (PAR300: p = 0.067; PAR1100: p = 0.100) pools, and higher beta-Car/Chl a pools (PAR300: p < 0.001) compared to the control plants. Also, Chl a/Chl b pools were significantly higher (PAR300: p = 0.004, PAR1100: p = 0.006) in the recovered water deficit plants.

Relative pigment pools normalized by Chl a content (mean ± SE in mol/mol, n = 5 for water-deficit leaves on D3 PAR300; n = 6 for all the others). Neo, Ant, Vio, Zea, beta-Car, and Lut are shown, as well as the Chl a /Chl b ratio. Sampling corresponds to two light conditions (PAR300 and PAR1100) on key days: D1 (early stress), D3 and D7 (stress), and D15 (recovery). The significance level between treatments is given as: *(p-value < 0.05), **(p-value < 0.01); ***(p-value < 0.001). Shapiro–Wilk test was applied as normality prove; Levene as homogeneity of variances test; t-test for normal distributed data; and Kruskal–Wallis for non-normal distributed data.

Overall, the day of sampling had a significant effect on most of the relative pools (Supplementary Table S4), both in control and treatment plants. Under low light, significant changes were observed in water deficit plants for relative Lut, Zea, Ant and beta-car, while control plants showed significant differences in beta-car, Chl a/Chl b, Neo and Zea pools. Under high light, both treatments exhibited significant changes in relative Ant pools. Additionally, control also exhibited differences in relative Neo, whereas water deficit plants exhibited differences in Chl a/Chl b, and relative Lut and beta-car pools. Pooling all sampling days, the effect of PAR had a clear impact (p < 0.001) on the relative Vio and Zea pools for both treatments (Supplementary Table S5). Interestingly, for water deficit plants, Chl a/Chl b ratio increased also overall significantly (p = 0.007) between PAR300 and PAR1100 across the experiment.

Discussion

Potential of proximal imaging spectroscopy to reveal in vivo antenna adjustments

The regulation of light absorption in response to excessive light exposure is an intrinsic property of the leaf, with absorbance variations driven by the pigment concentration47,48, and their interaction with their environment49,50. A rapid decrease in pigment content was already noticeable on D3 (Supplementary Table S2). The loss of chlorophyll, and the resulted reduction in photon absorption, is typically identified as a stress response51 and related to pigment photooxidation happening due to the excessive amount of energy absorbed52. It may be a species dependent mechanism53, but certainly is not the only or major antenna mechanism to cope with excessive light (see “Pigment pool adjustments: Chl a/Chl b and Xan/Chl a” section). We observe a decrease in Foʹ manifested during drought (Fig. 3a) due to the significant loss in the absolute overall pigment pool54,55, which is also the primary reason for the visual decrease in canopy reflectance along the full 500–800 nm range56, observed along the days D1-D2-D3 (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Changes in the red edge region, either through reflectance indices or first derivative analysis, are often used for tracking leaf or canopy stress57,58,59,60. While we observe clear canopy reflectance changes taking place from the early stress days (D1-D2-D3) onward (Supplementary Fig. S3), no strong change in the R’ between control and water deficit plants was observed. Meanwhile, Chl content showed however a significant reduction (Supplementary Table S2). As stress progressed, derivative analysis could however monitor additional true absorbance changes, illustrating a gradual modification of the true shape of the canopy reflectance for the water deficit plants (Fig. 5). These changes are seen in parallel with repeated ΔA changes in the red-edge, with highest peak differences (2–4% in ΔA) observed during the final stress days (Figs. 4, S5). Also control plants showed daily consistent red peak (695-nm) ΔA shifts of approx. 4% upon illumination of only 300 μmol m−2 s−1 (Supplementary Fig. S5). In contrast to the water-deficit plants, their Rdark’s first derivative remained relatively stable along the experiment. We suggest that the observed ΔA in control plants could prove a rather reversible mechanism which may largely recover during the night phase. In the case of the water-deficit plants, Rʹ indicates a stronger enhanced modification of the absorbance shape along the stress phase, showing a broadening towards low-energy wavelengths. This is indicative of a cumulated effect of the true absorbance changes, which does not relax overnight. These modified R shape changes could, however, reverse during the first days of the recovery phase. Although we did not observe a clear double-peak feature in the red-edge Rʹ as shown by others works29,30,59, we similarly observed a shift of the derivative peak towards lower wavelengths during stress (Fig. 5). We devote this shift to the true, red-shifted absorbance consistently seen at the whole plant level.

In comparison to the whole-plant observations, leaf-level reflectance observations exhibited a larger variability (Supplementary Fig. S8), probably due to the limited sampling size and more random sampling during the experiment (difference features were obtained from different leaves at different times). This likely hindered the identification of specific trends in the absorbance spectrum, as would have been expected from previous observations under more controlled set-ups19. Estimated true surface absorbance differences derived from the canopy reflectance, on the other hand, showed a high consistency (Supplementary Fig. S5), which can be explained as due to a better overall representation of the overall adjustments at the whole-plant scale, integrating all signals from multiple leaves in varying positions and conditions.

Two-step antenna adjustments at low and high amount of energy excess

In accordance with other studies performed either from leaves or isolated antenna complexes33,61,62, we could distinguish red-shifted adjustments of the antenna absorption between unquenched and quenched antenna states from the canopy reflectance signal (Figs. 4, 7). The origin of the red-shifted or so-called “low-energy Chl”62,63,64,65,66, or low-energy states observed for several types of LHCs has been explained using models that use exciton/charge transfer mixed states but without any clear agreement established so far. In contrast, long-wavelength chlorophyll species were associated with amplification of high energy-state excitation quenching by Ruban et al.16. Due to their complexity, the molecular processes underlying the quenching of the energy are not yet sufficiently understood and are still the subject of active debate67,68. There is for example no full consensus on the origin of the changes in either the green and red absorption region (Figs. 2, 4), the coordination between the changes in both spectral regions, nor the form of energy dissipation. Agreement however exists on (1) the light-harvesting antenna pigment-protein complexes acting as a highly dynamic structure which can adapt and fine-tune to different energy states, e.g. through the reversible dissociation of LHCII from the PSII core complex68,69,70, (2) the chemical conversion of xanthophylls, and (3) the use of ultrafast energy relaxation within the Q bands of chlorophyll71. Here, we show that canopy-based difference spectra can witness the early antenna adjustments (695-nm peak) similar to those obtained by transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy performed on purified LHCII72. Instead of using an ultrafast probing technique, we observe similar ΔA features along the gradual antenna adaptation to the excess of light at the whole plant level. A further broadened far-red absorbance (> 700 nm) appears under increasing excessive light exposure (Fig. 7c), implying a stronger structural impact at the antenna level. Comparable experimental proof of the shifted and broadened absorbance has been shown at the intact leaf level occurring under a slow-induced kinetical trend indicating protein-controlled conformational changes of the pigment bed19.

Any modification in the true absorbance behaviour would also be expected to translate to the fluorescence emission states. As it appears, a fast and slow quenching mechanism different in triggers and activation time was also proposed based on in vivo fluorescence life time analysis73. Both red-shifted (~ 690 nm) and strongly far-red (> 700 nm) enhanced fluorescence components were distinguished for quenched states15,33,73,74. Interestingly, also spectral decomposition analysis of passively-emitted fluorescence has pointed to subtle changes around these peak components, pointing to structural rearrangements in the antenna independently of the Chl content, with a link to sustained quenching behaviour75. It remains however to be verified how in vivo antenna absorbance shifts and fluorescence components are connected to each other.

Rewatering reversed the far-red changes in the red-edge region upon the first day of recovery (Figs. 4, 5), suggesting that these broadening effects are associated with well-regulated and reversible dynamics observable at the canopy scale. This was accompanied by a recovery of QY values starting from the day after rewatering and gradually returning to the initial healthy levels.

Pigment pool adjustments: Chl a/Chl b and Xan/Chl a

Apart from obvious loss in the total pigment pool, specific stoichiometric changes among the different pools took place, illustrating the plasticity in the photosynthetic antenna under stress. For example, at D3 drought stressed plants showed a significant (p-value < 0.001) decrease in Chl a/Chl b ratio at PAR1100 (Fig. 8), indicating an increased relative importance for the Chl b pool size. Interestingly, the ratio also showed an additional decrease with higher PAR in water-deficit plants (p-value = 0.007), which was not observed in control plants (Supplementary Table S5). This demonstrates that the Chl a versus Chl b pigment composition can be fine-tuned under stress. Although the use of the Chl a/Chl b ratio to track changes in antenna size is well established for long term light exposure acclimations, the extent of its role in the (fast) photoprotective response is less clear. Our results may challenge the idea that plants only adjust their Chl a/Chl b ratio solely based on daily light integral or long-term light acclimation53,76,77,78. Short-term conversions between Chl a and Chl b take place through the chlorophyll cycle, which acts in the construction and destruction of the LHC79 and follows a distinct signaling pathway compared to longer-term transductions80. From in vitro recombinant LHC studies a mixed occupancy of Chl a and Chl b has been predicted and shown at certain antenna locations81,82, which could point to a strategy to quickly alter the energy transfer at specific sites in the antenna. Further, Chl b-less mutants in higher plants have shown reduced levels of NPQ83, which has been explained by the essential role of Chl b in the proper folding and function of the LHC complexes79,84,85. Here, our results also support a key role of an increased Chl b pool in the establishing of the quenched states.

In contrast to the less clear role of Chl b in the activation of the energy-dissipation mechanisms, xanthophylls play an unneglectable role7. We observed a significant increase of Ant, Lut and Neo under drought stress (Fig. 8) on the one hand, while an additional rise of the Zea pool took place under additional light stress for both treatments on the other hand (Supplementary Table S5). It demonstrates that both xanthophyll cycles have a functional and synergistic role to play in the photoprotection of the antenna86. Previous studies have demonstrated that Lut plays a crucial role in regulating drought response87,88, increasing NPQ values and protecting the plants against photoinhibition. However, Lut did not seem to be further sensitive to changes in light intensity, as no significant differences were observed under increased PAR values (Supplementary Table S5). Clearly, Zea took this role, being known for modulation of the quenching activity during high light acclimation3,70,89,90. Additionally, Zea’s contribution enhancing stress memory91,92 appears to facilitate the recovery response, observed by the higher QY performance during recovery (Fig. 3c), which is aligned with previous findings41,93.

While the link between accumulation of different xanthophylls and the activation of regulated heat dissipation is obvious from experimental evidence, as illustrated also for tomato41, distinguishing the spectral behavior of the individual quenchers within the ΔA changes is less trivial. Apart from other described influences in the dynamic 500–600 nm region, specific features modeled as Gaussians have been associated with the overlapping activation of different xanthophylls94, but the individual contributions are not clear so far. A ΔA peak shift (520 → 530 nm) in the green region during PAR increase for control plants and further ΔA peak shift (530 → 560 nm) under drought (Supplementary Fig. S6) highlight a stepwise acclimation in the 500–600 nm region. These observations point to a certain limitation of using fixed spectral Indices such as PRI which may not capture the potential role of different xanthophylls along the cascade of quenching energy. Their role and link within the two-step red-shifted energy redistribution remains to be elucidated.

Conclusions

In analogy to transient absorption spectroscopy techniques applied to isolated antenna complexes, our results demonstrate the high potential of non-destructive imaging spectroscopy to track the antenna energy redistribution during quenched states, triggered by drought and excessive excitation pressure. Changes in the canopy reflectance demonstrate a two-step antenna-driven adjustment with impact in both the green (500–600 nm) and red-edge (680–750 nm) region during the process of energy quenching. The novelty of our work is that such specific high spectral-resolution absorbance changes can be demonstrated in vivo, at the canopy level, and interpreted along progressive light and additional stress conditions. Future improvements for the spectral detection and decoupling of these actual photosynthesis-related antenna adjustments, with the aim to resolve the energy balance quantitatively, should still consider (1) the multilayer scattering effects, (2) fractional cover effects or signal complexity due to the soil background, (3) the separation of overlapping biochemical and conformational changes, and (4) the impact of the latter mechanisms on the quenching behaviour. Unravelling these different contributions can foster promising strategies to derive actual photosynthesis dynamics applicable to larger monitoring scales.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Blankenship, R. E. Structural and functional dynamics of photosynthetic antenna complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 13751–13752 (2015).

Ort, D. R. When there is too much light. Plant Physiol. 125, 29–32 (2001).

Bassi, R. & Dall’Osto, L. Dissipation of light energy absorbed in excess: The molecular mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 72, 47–76 (2021).

Barber, J. & Andersson, B. Too much of a good thing: Light can be bad for photosynthesis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 17, 61–66 (1992).

Karpiński, S., Szechyńska-Hebda, M., Wituszyńska, W. & Burdiak, P. Light acclimation, retrograde signalling, cell death and immune defences in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 36, 736–744 (2013).

Lambrev, P. H., Miloslavina, Y., Jahns, P. & Holzwarth, A. R. On the relationship between non-photochemical quenching and photoprotection of Photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 760–769 (2012).

Ruban, A. V. Nonphotochemical chlorophyll fluorescence quenching: Mechanism and effectiveness in protecting plants from photodamage. Plant Physiol. 170, 1903–1916 (2016).

Betterle, N. et al. Light-induced dissociation of an antenna hetero-oligomer is needed for non-photochemical quenching induction. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 15255–15266 (2009).

Demmig-Adams, B. Carotenoids and photoprotection in plants: A role for the xanthophyll zeaxanthin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Bioenerg. 1020, 1–24 (1990).

García-Plazaola, J. I., Matsubara, S. & Osmond, C. B. The lutein epoxide cycle in higher plants: Its relationships to other xanthophyll cycles and possible functions. Funct. Plant Biol. 34, 759–773 (2007).

Leuenberger, M. et al. Dissecting and modeling zeaxanthin- and lutein-dependent nonphotochemical quenching in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114, E7009–E7017 (2017).

Horton, P. et al. Control of the light-harvesting function of chloroplast membranes by aggregation of the LHCII chlorophyll-protein complex. FEBS Lett. 292, 1–4 (1991).

Ruban, A. V., Young, A. & Horton, P. Modulation of chlorophyll fluorescence quenching in isolated light harvesting complex of Photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Bioenerg. 1186, 123–127 (1994).

Ware, M. A., Giovagnetti, V., Belgio, E. & Ruban, A. V. PsbS protein modulates non-photochemical chlorophyll fluorescence quenching in membranes depleted of photosystems. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 152, 301–307 (2015).

Chmeliov, J. et al. The nature of self-regulation in photosynthetic light-harvesting antenna. Nat. Plants 2, 1–7 (2016).

Ruban, A. V., Rees, D., Noctor, G. D., Young, A. & Horton, P. Long-wavelength chlorophyll species are associated with amplification of high-energy-state excitation quenching in higher plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Bioenerg. 1059, 355–360 (1991).

Buschmann, C. & Prehn, H. Photoacoustic spectroscopy—photoacoustic and photothermal effects. In Physical Methods in Plant Sciences (eds Linskens, H.-F. & Jackson, J. F.) 148–180 (Springer, 1990).

Nagel, E. M., Buschmann, C. & Lichtenthaler, H. K. Photoacoustic spectra of needles as an indicator of the activity of the photosynthetic apparatus of healthy and damaged conifers. Physiol. Plant. 70, 427–437 (1987).

Van Wittenberghe, S., Alonso, L., Malenovský, Z. & Moreno, J. In vivo photoprotection mechanisms observed from leaf spectral absorbance changes showing VIS–NIR slow-induced conformational pigment bed changes. Photosynth. Res. 142, 283–305 (2019).

Bilger, W., Björkman, O. & Thayer, S. S. Light-induced spectral absorbance changes in relation to photosynthesis and the epoxidation state of xanthophyll cycle components in cotton leaves. Plant Physiol. 91, 542–551 (1989).

Brugnoli, E. & Björkman, O. Chloroplast movements in leaves: Influence on chlorophyll fluorescence and measurements of light-induced absorbance changes related to ΔpH and zeaxanthin formation. Photosynth. Res. 32, 23–35 (1992).

Kramer, D. M. & Sacksteder, C. A. A diffused-optics flash kinetic spectrophotometer (DOFS) for measurements of absorbance changes in intact plants in the steady-state. Photosynth. Res. 56, 103–112 (1998).

Cazzaniga, S., Dall’Osto, L., Kong, S.-G., Wada, M. & Bassi, R. Interaction between avoidance of photon absorption, excess energy dissipation and zeaxanthin synthesis against photooxidative stress in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 76, 568–579 (2013).

Thomas, J. R. & Gausman, H. W. Leaf reflectance vs. Leaf chlorophyll and carotenoid concentrations for eight crops1. Agron. J. 69, 799–802 (1977).

Baret, F., Jacquemoud, S., Guyot, G. & Leprieur, C. Modeled analysis of the biophysical nature of spectral shifts and comparison with information content of broad bands. Remote Sens. Environ. 41, 133–142 (1992).

Gitelson, A. A., Keydan, G. P. & Merzlyak, M. N. Three-band model for noninvasive estimation of chlorophyll, carotenoids, and anthocyanin contents in higher plant leaves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, (2006).

Wu, C., Niu, Z., Tang, Q. & Huang, W. Estimating chlorophyll content from hyperspectral vegetation indices: Modeling and validation. Agric. For. Meteorol. 148, 1230–1241 (2008).

Main, R. et al. An investigation into robust spectral indices for leaf chlorophyll estimation. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 66, 751–761 (2011).

le Maire, G., François, C. & Dufrêne, E. Towards universal broad leaf chlorophyll indices using PROSPECT simulated database and hyperspectral reflectance measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 89, 1–28 (2004).

Zarco-Tejada, P. J., Pushnik, J. C., Dobrowski, S. & Ustin, S. L. Steady-state chlorophyll a fluorescence detection from canopy derivative reflectance and double-peak red-edge effects. Remote Sens. Environ. 84, 283–294 (2003).

French, C. S., Brown, J. S. & Lawrence, M. C. Four universal forms of chlorophyll a. Plant Physiol. 49, 421 (1972).

Ilioaia, C., Johnson, M. P., Horton, P. & Ruban, A. V. Induction of efficient energy dissipation in the isolated light-harvesting complex of photosystem II in the absence of protein aggregation∗. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29505–29512 (2008).

Johnson, M. P. & Ruban, A. V. Photoprotective energy dissipation in higher plants involves alteration of the excited state energy of the emitting chlorophyll(s) in the light harvesting antenna II (LHCII)*. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23592–23601 (2009).

Curtiss, B. & Ustin, S. L. Parameters affecting reflectance of coniferous forests in the region of chlorophyll pigment absorption. in 12th Canadian Symposium on Remote Sensing Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, vol. 4, 2633–2636 (1989).

Ustin, S. L. et al. Retrieval of foliar information about plant pigment systems from high resolution spectroscopy. Remote Sens. Environ. 113, S67–S77 (2009).

Gamon, J. A. et al. Remote sensing of the xanthophyll cycle and chlorophyll fluorescence in sunflower leaves and canopies. Oecologia 85, 1–7 (1990).

Gamon, J. A. & Surfus, J. S. Assessing leaf pigment content and activity with a reflectometer. New Phytol. 143, 105–117 (1999).

Ripullone, F. et al. Effectiveness of the photochemical reflectance index to track photosynthetic activity over a range of forest tree species and plant water statuses. Funct. Plant Biol. 38, 177–186 (2011).

Wong, C. Y. S. & Gamon, J. A. Three causes of variation in the photochemical reflectance index (PRI) in evergreen conifers. New Phytol. 206, 187–195 (2015).

Moncholi-Estornell, A. et al. Enhancing solar-induced fluorescence interpretation: Quantifying fractional sunlit vegetation cover using linear spectral unmixing. Remote Sens. 15, 4274 (2023).

Pescador-Dionisio, S. et al. In vivo detection of spectral reflectance changes associated with regulated heat dissipation mechanisms complements fluorescence quantum efficiency in early stress diagnosis. New Phytol. 245, 559–576 (2025).

Widlowski, J.-L. et al. Third radiation transfer model intercomparison (RAMI) exercise: Documenting progress in canopy reflectance models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 112, (2007).

Alonso, L. et al. Diurnal cycle relationships between passive fluorescence, PRI and NPQ of vegetation in a controlled stress experiment. Remote Sens. 9, 770 (2017).

Van Wittenberghe, S. et al. Upward and downward solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence yield indices of four tree species as indicators of traffic pollution in Valencia. Environ. Pollut. 173, 29–37 (2013).

Rodrigo, M. J., Cilla, A., Barberá, R. & Zacarías, L. Carotenoid bioaccessibility in pulp and fresh juice from carotenoid-rich sweet oranges and mandarins. Food Funct. 6, 1950–1959 (2015).

Rodrigo, M. J. et al. A mutant allele of ζ-carotene isomerase (Z-ISO) is associated with the yellow pigmentation of the “Pinalate” sweet orange mutant and reveals new insights into its role in fruit carotenogenesis. BMC Plant Biol. 19, 465 (2019).

Im, J. & Jensen, J. R. Hyperspectral remote sensing of vegetation. Geogr. Compass 2, 1943–1961 (2008).

Mirkovic, T. et al. Light absorption and energy transfer in the antenna complexes of photosynthetic organisms. Chem. Rev. 117, 249–293 (2017).

Ballottari, M., Dall’Osto, L., Morosinotto, T. & Bassi, R. Contrasting behavior of higher plant photosystem I and II antenna systems during acclimation*. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 8947–8958 (2007).

Jacquemoud, S. & Ustin, S. Leaf Optical Properties (Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Esteban, R. et al. Internal and external factors affecting photosynthetic pigment composition in plants: A meta-analytical approach. New Phytol. 206, 268–280 (2015).

Elvira, S., Alonso, R., Castillo, F. J. & Gimeno, B. S. On the response of pigments and antioxidants of Pinus halepensis seedlings to Mediterranean climatic factors and long-term ozone exposure. New Phytol. 138, 419–432 (1998).

Galmés, J., Abadía, A., Cifre, J., Medrano, H. & Flexas, J. Photoprotection processes under water stress and recovery in Mediterranean plants with different growth forms and leaf habits. Physiol. Plant. 130, 495–510 (2007).

Strasser, R. J., Tsimilli-Michael, M. & Srivastava, A. Analysis of the chlorophyll a fluorescence transient. In Chlorophyll a Fluorescence: A Signature of Photosynthesis (eds Papageorgiou, G. C. & Govindjee) 321–362 (Springer, 2004).

Li, R., Guo, P., Michael, B., Stefania, G. & Salvatore, C. Evaluation of chlorophyll content and fluorescence parameters as indicators of drought tolerance in Barley. Agric. Sci. China 5, 751–757 (2006).

Galieni, A. et al. Past and future of plant stress detection: An overview from remote sensing to positron emission tomography. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 609155 (2021).

Miller, J. R., Hare, E. W. & Wu, J. Quantitative characterization of the vegetation red edge reflectance 1. An inverted-Gaussian reflectance model. Int. J. Remote Sens. 11, 1755–1773 (1990).

Curran, P. J., Windham, W. R. & Gholz, H. L. Exploring the relationship between reflectance red edge and chlorophyll concentration in slash pine leaves. Tree Physiol. 15, 203–206 (1995).

Smith, K. L., Steven, M. D. & Colls, J. J. Use of hyperspectral derivative ratios in the red-edge region to identify plant stress responses to gas leaks. Remote Sens. Environ. 92, 207–217 (2004).

Abdullah, H., Skidmore, A. K., Darvishzadeh, R. & Heurich, M. Timing of red-edge and shortwave infrared reflectance critical for early stress detection induced by bark beetle (Ips typographus, L.) attack. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 82, 101900 (2019).

Morosinotto, T., Caffarri, S., Dall’Osto, L. & Bassi, R. Mechanistic aspects of the xanthophyll dynamics in higher plant thylakoids. Physiol. Plant. 119, 347–354 (2003).

Romero, E. et al. The origin of the low-energy form of photosystem I light-harvesting complex Lhca4: Mixing of the lowest exciton with a charge-transfer state. Biophys. J. 96, L35–L37 (2009).

Novoderezhkin, V. I. et al. Mixing of exciton and charge-transfer states in light-harvesting complex Lhca4. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 19368–19377 (2016).

Croce, R. et al. The low-energy forms of photosystem I light-harvesting complexes: Spectroscopic properties and pigment-pigment interaction characteristics. Biophys. J. 93, 2418–2428 (2007).

Reimers, J. R. et al. Challenges facing an understanding of the nature of low-energy excited states in photosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Bioenerg. 1857, 1627–1640 (2016).

Vaitekonis, S., Trinkunas, G. & Valkunas, L. Red chlorophylls in the exciton model of photosystem I. Photosynth. Res. 86, 185–201 (2005).

Krüger, T. P. J., Ilioaia, C., Johnson, M. P., Ruban, A. V. & van Grondelle, R. Disentangling the low-energy states of the major light-harvesting complex of plants and their role in photoprotection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Bioenerg. 1837, 1027–1038 (2014).

Liguori, N. et al. Different carotenoid conformations have distinct functions in light-harvesting regulation in plants. Nat. Commun. 8, 1994 (2017).

Müller, P., Li, X.-P. & Niyogi, K. K. Non-photochemical quenching. A response to excess light energy1. Plant Physiol. 125, 1558–1566 (2001).

Xu, P., Tian, L., Kloz, M. & Croce, R. Molecular insights into Zeaxanthin-dependent quenching in higher plants. Sci. Rep. 5, 13679 (2015).

Reiter, S., Bäuml, L., Hauer, J. & de Vivie-Riedle, R. Q-Band relaxation in chlorophyll: New insights from multireference quantum dynamics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 27212–27223 (2022).

Ruban, A. V. et al. Identification of a mechanism of photoprotective energy dissipation in higher plants. Nature 450, 575–578 (2007).

Holzwarth, A., Miloslavina, Y., Nilkens, M. & Jahns, P. Identification of two quenching sites active in the regulation of photosynthetic light-harvesting studied by time-resolved fluorescence. Chem. Phys. Lett. 483, 262–267 (2009).

Miloslavina, Y. et al. Far-red fluorescence: A direct spectroscopic marker for LHCII oligomer formation in non-photochemical quenching. FEBS Lett. 582, 3625–3631 (2008).

Rajewicz, P. A. et al. The photosynthetic response of spectral chlorophyll fluorescence differs across species and light environments in a boreal forest ecosystem. Agric. For. Meteorol. 334, 109434 (2023).

Björkman, O. & Demmig-Adams, B. Regulation of photosynthetic light energy capture, conversion, and dissipation in leaves of higher plants. In Ecophysiology of Photosynthesis (eds Schulze, E.-D. & Caldwell, M. M.) 17–47 (Springer, 1995).

Sapeta, H. et al. Reversible down-regulation of photosystems I and II leads to fast photosynthesis recovery after long-term drought in Jatropha curcas. J. Exp. Bot. 74, 336–351 (2023).

Poorter, H. et al. A meta-analysis of plant responses to light intensity for 70 traits ranging from molecules to whole plant performance. New Phytol. 223, 1073–1105 (2019).

Tanaka, R. & Tanaka, A. Chlorophyll cycle regulates the construction and destruction of the light-harvesting complexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Bioenerg. 1807, 968–976 (2011).

Masuda, T., Tanaka, A. & Melis, A. Chlorophyll antenna size adjustments by irradiance in Dunaliella salina involve coordinate regulation of chlorophyll a oxygenase (CAO) and Lhcb gene expression. Plant Mol. Biol. 51, 757–771 (2003).

Belgio, E. & Ruban, A. V. Recombinant light harvesting complexes: Views and perspectives. In Photosynthesis: Structures, Mechanisms, and Applications (eds Hou, H. J. M. et al.) 33–49 (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

Seki, M., Umezawa, T., Urano, K. & Shinozaki, K. Regulatory metabolic networks in drought stress responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10, 296–302 (2007).

Zhang, L., Yang, C. & Liu, C. Revealing the significance of chlorophyll b in the moss Physcomitrium patens by knocking out two functional chlorophyllide a oxygenase. Photosynth. Res. 158, 171–180 (2023).

Plumley, F. G. & Schmidt, G. W. Reconstitution of chlorophyll a/b light-harvesting complexes: Xanthophyll-dependent assembly and energy transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 84, 146–150 (1987).

Plumley, G. F. & Schmidt, G. W. Light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b complexes: Interdependent pigment synthesis and protein assembly. Plant Cell 7, 689–704 (1995).

Bonente, G., Dall’Osto, L. & Bassi, R. In between photosynthesis and photoinhibition: The fundamental role of carotenoids and carotenoid-binding proteins in photoprotection. In Biophotonics (eds Pavesi, L. & Fauchet, P. M.) 29–46 (Springer, 2008).

Yan, J. et al. TgLUT1 regulated by TgWRKY10 enhances the tolerance of Torreya grandis to drought stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. PPB 207, 108436 (2024).

Wang, S. et al. Overexpression of a tomato carotenoid ε-hydroxylase gene (SlLUT1) improved the drought tolerance of transgenic tobacco. J. Plant Physiol. 222, 103–112 (2018).

Dall’Osto, L. et al. Zeaxanthin protects plant photosynthesis by modulating chlorophyll triplet yield in specific light-harvesting antenna subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 41820–41834 (2012).

Nilkens, M. et al. Identification of a slowly inducible zeaxanthin-dependent component of non-photochemical quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence generated under steady-state conditions in Arabidopsis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Bioenerg. 1797, 466–475 (2010).

Jahns, P. & Holzwarth, A. R. The role of the xanthophyll cycle and of lutein in photoprotection of photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 182–193 (2012).

Murchie, E. H. Safety conscious or living dangerously: What is the ‘right’ level of plant photoprotection for fitness and productivity?. Plant Cell Environ. 40, 1239–1242 (2017).

Dall’Osto, L., Caffarri, S. & Bassi, R. A mechanism of nonphotochemical energy dissipation, independent from PsbS, revealed by a conformational change in the antenna protein CP26. Plant Cell 17, 1217–1232 (2005).

Van Wittenberghe, S. et al. Combined dynamics of the 500–600 nm leaf absorption and chlorophyll fluorescence changes in vivo: Evidence for the multifunctional energy quenching role of xanthophylls. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Bioenerg. 1862, 148351 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The research in this paper was conducted in the framework of ERC-2021-STG project “PHOTOFLUX”, funded by the European Research Council (grant no. 101041768). The R&D&I infrastructure and equipment (PlantScreenTM system) was financed by the European Union through the operational program of the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) of the Valencian Community (Project no. IDIFEDER/2018/050). We would like to acknowledge Dr. Luis Alonso the original concept of the chamber design. HPLC pigment analyses were supported by funding from the award of the Spanish government to the IATA-CSIC as Center of Excellence Accreditation Severo Ochoa (CEX2021-001189-S/ MCIU/AEI /10.13039/501100011033). Further we would like to thank Sergio G. Nebauer for providing the tomato plants and Cynthia Chardi-Raga for lab assistance during the experiment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CGM and SVW designed the study and wrote the manuscript, AME and CGM performed the fluorescence and spectral image analyses, CGM and SPD performed the leaf spectroscopy measurements and analyses, SPD performed the pigment analyses, MJR supervised the pigment analyses, MPCM and JM contributed to the original manuscript, SVW supervised the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

García-Martínez, C., Moncholi-Estornell, A., Pescador-Dionisio, S. et al. Canopy imaging spectroscopy reveals a stepwise redshifted energy redistribution in the antenna under drought stress. Sci Rep 15, 17241 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01940-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-01940-0