Abstract

Phosphorus is crucial for marine phytoplankton viability as a key biogenic element. Under phosphorus deficiency, dinoflagellates exhibit changes in their feeding regime, alterations in transporters functioning, a reduction in cell proliferation rate and, in some cases, a transition to sexual reproduction. In this study, we performed RNA-sequencing analysis to assess the transcriptomic response of the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum cordatum to phosphorus deficiency in the cultivation medium. The aim of this work was to elucidate shifts in P. cordatum life cycle under these conditions focusing on the increase in the percentage of cells with a relative nuclear DNA content of 2C and the appearance of 4C cells, which may indicate a transition to the sexual process. We identified 196 differentially expressed genes – 169 up-regulated and 27 down-regulated—in cells grown for 14 days under phosphorus-depleted conditions. Analysis revealed up-regulation of pathways for phosphate uptake and assimilation, along with activation of RNA, protein, and lipid metabolic processes. Additionally, mechanisms regulating the cell cycle and inducing meiotic division were triggered. We identified up-regulated genes encoding proteins involved in meiotic recombination, including those promoting crossover. These findings indicate that phosphorus limitation can induce shift to sexual phase in P. cordatum life cycle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Phosphorus availability has a significant impact on the vital capacity of marine phytoplankton and, consequently, on primary production in the ocean. Phosphorus is a biogenic element that plays a crucial role in the cells of living organisms, since it is а fundamental component of nucleic acids, phospholipids and signal molecules; it is also involved in the transmission of chemical energy through the ATP molecules1. Moreover, phosphorylation/dephosphorylation cycle regulates the activity of the enzymes necessary for the maintenance of basic metabolic pathways, including regulation of the cell cycle2. Phosphorus, as orthophosphate, plays a key role in photosynthesis, i.e. primary productivity1. The orthophosphate ions (Pi) are preferentially utilized by phytoplankton because it can be directly taken up and assimilated to support algal metabolism and growth3. Phosphate is a limiting nutrient and is present at an extremely low concentration in the surface waters of the open oceans4. Due to high nitrogen pollution in the coastal waters, these areas become phosphorus limited5.

Most photosynthetic dinoflagellates are mixotrophs, so they can switch between different nutrient uptake pathways depending on nutrient availability6. Phosphorus deficiency induces phagotrophy in some species, alters the functioning of transporters, changes enzyme activity, and reduces photosynthesis efficiency and cell proliferation rate7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. In particular, the cell cycle appears to be arrested in the G0/G1 phase10,11. Recent studies demonstrated that dinoflagellates can replace phospholipids with glycerol glycolipids and betaine lipids15. Moreover, phosphate deficiency can lead to a transition to the sexual process. For this transition, phosphate starvation can be either sufficient external factor on its own16,17, or it may have an effect in conjunction with a deficiency of another nutrient, e.g. nitrate18,19, or in combination with other stressors, such as changes in temperature and salinity20.

Recently, we showed that phosphorus limitation induced a shift in the life cycle progress in Prorocentrum cordatum: a sharp increase in the percentage of cells with relative nuclear DNA content 2C and the appearance of cells with relative nuclear DNA content 4C21. This trend emerged on the 9th day of the experiment and reached a plateau in 15 days. Subsequent supplementation with a phosphate-containing medium resulted in a significant increase in the number of 4C cells and a further return to the control ratio of DNA content values21. We suggested that these dynamics might indicate the occurrence of sexual reproduction in response to nutrient deficiency21. To elucidate molecular mechanisms involved in the observed processes in P. cordatum cells, we analyzed their transcriptomic response to phosphorus deficiency in the same conditions.

Results

Culture growth, phosphate uptake, and nuclear DNA content

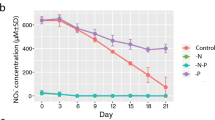

To obtain Prorocentrum cordatum cell samples for RNA extraction and subsequent RNA sequencing and differential expression analysis, we performed an experiment on culture growing under phosphate limitation for 14 days in accordance with Kalinina and co-authors’ protocol21. Our observations were consistent with the previously obtained results. The phosphate concentration gradually decreased in the control, while in P-limited cultures it was undetectable starting from day 3 (Fig. 1a). The growth rates were generally similar in control and P-deprived cultures – the average rates were 0.09 ± 0.03 d-1 and 0.06 ± 0.05 d-1, respectively (Fig. 1b, Suppl. Table 1). In the latter, there was a decrease in cell number by the end of the experiment; but the difference when compared to the control cultures was not statistically significant (Fig. 1b, Suppl. Tables 1, 2). However, flow cytometry analysis revealed that the fraction of cells with relative DNA content 2C significantly increased to 30.7%±2.0% on day 14 in P-deficient cultures, in contrast to the control ones, where it was 14.2%±0.5% (Fig. 1с, Suppl. Tables 3, 4), suggesting the early response to P-stress and initiation of the first stages of the sexual process. So, this time point was chosen for cell sampling and subsequent transcriptome analysis.

(a) Dynamics of phosphate concentration in the control and experimental (P-deficient) cultures of Prorocentrum cordatum. (b) Growth curves of P. cordatum in the control and experimental (P-deficient) cultures. (c) Percentage of P. cordatum cells with different relative nuclear DNA content on days 0, 12, and 14 of cultivation in the control and P-deficient cultures. The data presented are mean values ± standard errors of the mean (a, b) or mean values only (c), derived from triplicate experiments.

RNA sequencing results

RNA sequencing was performed on six RNA samples – three samples from control cultures and three samples from P-limited cultures. On average, 165 846 167 raw reads with adapters removed were obtained per sample. The mean Q30 value indicating base calling accuracy score was ≥ 91.71%. After low quality reads removal, an average of 154 922 749 clean reads per sample (~ 15.6 Gb) were processed for genome-guided transcriptome assembly (Suppl. Table 5). The clean reads were mapped to the P. cordatum CCMP1329 reference genome presented by Dougan et al.22. In the analysis of differential gene expression, 50 365 genes were included (Suppl. Table 6).

Differential gene expression in cells subjected to phosphorus deficiency

To determine response of P. cordatum to phosphate depletion, the genes with fold change > 2 or < 0.5 (|log2(fold change)| > 1) and padj < 0.05 were further analyzed. Based on this criterion, 196 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) – 169 up-regulated and 27 down-regulated – were detected under P limitation conditions compared to control cultures (Fig. 2a). The principal component analysis (PCA) score plot revealed distance between the control and experimental groups and similarity between samples within them. PC1 and PC2 accounted for 83% and 7% of the variance, respectively (Suppl. Figure 1).

(a) Volcano plot depicting the pattern of differential gene expression in cells of P. cordatum at an early stage of the response to phosphate depletion. The X-axis displays the log2(fold change) values, Y-axis shows the significance level represented with -log10(padj), dots represent differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Significantly (|log2(fold change)| > 1, padj < 0.05) up-regulated DEGs are highlighted in red, and down-regulated DEGs are highlighted in blue. The horizontal dotted line marks the -log10(padj) value of 1.3, corresponding to padj = 0.05. The vertical dotted lines indicate log2(fold change) values of -1 and 1, respectively, which correspond to a two-fold change in the quantity of transcripts. (b) Violin plots depicting changes in the expression of up-regulated DEGs, grouped by the functions of the proteins they encode, in P. cordatum cells growing under phosphate-deficient conditions. The X-axis displays the functional group ID, while the Y-axis shows the log2(fold change) values. Dots represent genes. The functional groups are as follows: 1—homologues of proteins involved in phosphate transport and uptake; 2—components of molecular machineries involved in various protein metabolic processes; 3—homologues of proteins associated with RNA processing; 4—homologues of proteins associated with meiosis; 5—homologues of proteins involved in the regulation of cell cycle progression.

Among the selected DEGs, we could identify 91 protein-coding sequences among up-regulated genes and 12 sequences among down-regulated ones according to the results of a similarity search against the NCBI and UniProt databases (Suppl. Tables 7, 8). Some of these sequences were assigned Gene Ontology (GO) terms (Suppl. Tables 7, 8). We also checked with the results of functional annotation of P. cordatum protein-coding genes performed by Dougan with co-authors22 against Swiss-Prot and TrEMBL databases. Based on possible functions that are known for defined homologues, several groups can be distinguished among the up-regulated DEGs (Fig. 2b, Suppl. Table 7). The Group 1 comprises 10 genes that encode proteins involved in phosphate uptake and transport: putative H+-dependent inorganic phosphate transporter (protein ID: CAK0902791.1, fold change (FC) = 13.44), two homologues of Na+-dependent phosphate transporters (CAK0796258.1, FC = 5.30, CAK0847135.1, FC = 3.67), three SphX-like proteins that are presumably related to the ABC-type phosphate transport system (CAK0849911.1, FC = 9.63, CAK0843429.1, FC = 2.98, CAK0888660.1, FC = 4.06), and one predicted 5’-nucleotidase (CAK0831697.1, FC = 7.64) that plays the role in the phosphorus uptake from the organic source. We also included into this group three SPX-domain containing proteins (CAK0857988.1, FC = 2.15, CAK0866494.1, FC = 2.55, CAK0815579.1, FC = 2.15) that are possibly involved in phosphate metabolism and regulation of phosphorus homeostasis. Notably, most genes from this group exhibited the highest fold change values in expression among the DEGs analyzed (Suppl. Table 7).

The Group 2 includes 16 DEGs coding for proteins that could be assigned to molecular machineries providing protein metabolic processes, such as protein folding, ubiquitination, proteolysis – e.g. homologues of Rhomboid-related protein 3 (CAK0894647.1, FC = 10.44, CAK0858290.1, FC = 3.48), DnaJ domain-containing protein (CAK0830700.1, FC = 2.28, CAK0855537.1, FC = 2.00) and protein disulfide-isomerase A4 (CAK0812523.1, FC = 2.67), and probable RING-type E3 ubiquitin transferase LUL4 (CAK0795034.1, FC = 2.80). Besides, 10 DEGs associated with RNA processing (Group 3) – primarily, different splicing factors (e.g. homologue of splicing factor U2AF 65 kDa subunit CAK0815605.1, FC = 3.27) – increased their expression. Another discernible group (Group 4) consists of seven genes encoding proteins associated with meiosis. These are homologues of topoisomerase SPO11 mediating formation of double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA (CAK0793945.1, FC = 3.08), RAD51 recombinase responsible for homologous strand exchange (CAK0793887.1, FC = 2.55), MSH4 and MSH5 proteins promoting crossover (CAK0814171.1, FC = 3.50, and CAK0796672.1, FC = 3.09, respectively), exonuclease EXO1 (CAK0798514.1, FC = 2.82), and an element of the cohesin complex RAD21/REC8-like protein (CAK0895265.1, FC = 2.14). Besides, a DEG was revealed encoding a sequence (CAK0899742.1, FC = 2.39) identified by the InterProScan tool as a member of the meiosis specific protein Spo22/ZIP4/TEX11 family. Additionally, we detected four DEGs associated with phase transition in mitotic cycle (Group 5), including homologues of cyclin B (CAK0822172.1, FC = 2.88, CAK0845422.1, FC = 2.23) and cyclin A (CAK0858099.1, FC = 2.17) that regulate progression through the cell cycle, and sister chromatid cohesion protein PDS5 (CAK0805809.1, FC = 2.02).

Finally, several genes encoding transmembrane transporters that are not associated with phosphate transport were up-regulated. These include putative members of the ion transporter superfamily (Na+-sulfate cotransporters CAK0820761.1, FC = 5.92, and CAK0820762.1, FC = 2.22), the plant drug/metabolite exporter family (CAK0857002.1, FC = 2.63), and an ABC transporter domain-containing protein (CAK0852812.1, FC = 2.08) (Suppl. Table 7). We also revealed among up-regulated DEGs the ones that code for nitric oxide synthases (CAK0898375.1, FC = 2.61, CAK0898379.1, FC = 2.40), which catalyze the production of the signaling molecule nitric oxide, a homologue of phospholipase D (CAK0827941.1, FC = 2.18), hydrolyzing phospholipids, and one MEI2-like RRM domain-containing protein (CAK0795387.1, FC = 2.08) (Suppl. Table 7).

Among the DEGs with decreased expression, we could not distinguish any functional groups, with the exception of two genes encoding enzymes presumably involved in protein metabolic processes: a homologue of peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (CAK0849802.1, FC = 0.49) and a RING-type domain-containing protein (CAK0821132.1, FC = 0.13) (Suppl. Table 8). Additionally, we detected down-regulated genes coding for a homologue of the peptide transporter NPF8.1 (CAK0862783.1, FC = 0.45), a SulP family anion transporter (CAK0909116.1, FC = 0.39), a hexosyltransferase (CAK0824611.1, FC = 0.16), a MEI2-like RRM domain-containing protein (CAK0887363.1, FC = 0.27), and an SPX domain-containing protein (CAK0876587.1, FC = 0.33).

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the transcriptional response of the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum cordatum growing under deficiency of external sources of phosphorus for 14 days. We selected this time point for sampling because the number of cells with relative DNA content of 2 C sharply increased on this day, indicating a switch in the life cycle. The changes at the transcriptomic level, as reflected by the number of DEGs, were stable, although not abrupt. This can be attributed to the fact that the observed response at the cellular level was not total. Undoubtedly, only a fraction of cells in the population undergoes a life cycle transition. Moreover, the transcriptional response to the stressor may be less pronounced in P. cordatum even in comparison with closely related species. For example, Zhang with co-authors23 have detected significantly fewer DEGs in P. cordatum cells exposed to varying temperature and light conditions compared to those in P. micans.

The observed transcriptomic profile of P. cordatum growing under limitation of external sources of phosphorus reveals that certain pathways for phosphate uptake and assimilation are up-regulated in the cells. Additionally, RNA, protein, and lipid metabolic processes are activated, along with mechanisms related to sexual process and those regulating the cell cycle. Notably, we did not detect any effects on the expression of genes related to the photosynthetic apparatus, as has been shown for Fugacium kawagutii after one week of cultivation in P-deprived medium7 and for P. shikokuense (syn. P. donghaiense) after three days of growth in P-depleted conditions11. In some cases, phosphorus deficiency can promote heterotrophic behaviour. P. cordatum shifts to graze on cryptophyte algae under P-limitation14, but at the same time bacterivory in this species does not tend to be induced by such conditions24. We did not observe changes in the expression of genes related to endocytosis and phagocytosis in cells from P-limited cultures. Although we observed up-regulation of some genes encoding proteolytic enzymes, this may be attributed to protein turnover processes noted for microalgae in response to nutritional deficiency15,25,26.

We assume that P. cordatum cells begin to utilize their internal sources over the two-week period under conditions of external phosphorus deficiency. The increased expression of the gene encoding phospholipase D – phosphodiesterase, which is involved in the degradation of phospholipids – may indicate a transition to the remodeling of membrane phospholipids. Such a response to phosphorus limitation has been demonstrated in the dinoflagellates Karenia mikimotoi and P. shikokuense and is considered a first step in mobilizing intracellular phosphorus reservoirs15,27. The elevated expression of genes encoding 5’-nucleotidase and phosphate transporters also indicates the activation of mechanisms for phosphorus uptake from potential external sources. Furthermore, although the decrease in cell concentration in the experimental cultures was not significant, it rather corresponds to an early plateau in the growth curve observed previously21. This suggests that cell divisions may have ceased in the experimental cultures, potentially due to the gradual exhaustion of phosphorus resources. Thus, the state of the cells in our present work can apparently be considered an early stage of response to phosphorus deficiency.

Transport proteins generally have a range of substrate binding affinities (i.e., Ks values) but are typically divided into low- and high-affinity systems. Low-affinity transporters bind nutrients relatively weakly, resulting in high rates of dissociation back into the medium; however, they also transport and release the substrate into the cell quickly. Consequently, this system operates most efficiently at high phosphate concentrations. In contrast, high-affinity transport systems bind the substrate more tightly and release it into the cell more slowly. Transporters of this kind are more effective under substrate limitation3. Therefore, it is not surprising that under phosphate deficiency P. cordatum demonstrated a significant increase in the expression of the gene coding for the high affinity H+-dependent inorganic phosphate transporter homologous to PHO84 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. It is noteworthy that its amino acid sequence CAK0902791.1 identified in P. cordatum also shows similarities to the yeast glycerophosphodiester transporter GIT1, which mediates the uptake of glycerophosphoinositol and glycerophosphocholine as sources of the nutrients inositol and phosphate28. This P. cordatum protein has been designated as GIT1 by Dougan with co-authors22; sequences belonging to other dinoflagellate species annotated as GIT1 homologues can also be found in the databases. However, proton-coupled phosphate transporters are characterized by the presence of the glycine-rich phosphate binding motif GXGXGG in their sequences29. This feature is shared by CAK0902791.1 and the “GIT1” dinoflagellate sequences that we retrieved from the NCBI and UniProtKB databases (Suppl. Figure 2). Therefore, CAK0902791.1 is likely indeed a homologue of PHO84, and the identification of the other dinoflagellate proteins may need to be reconsidered. We also observed overexpression of two genes encoding Na+-dependent phosphate transporters. The expression levels of low-affinity Pi transporter genes homologous to S. cerevisiae PHO91 did not change compared to the control.

Dissolved organic phosphorus (DOP) is the main source of phosphorus during microalgae blooms, especially in a Pi-deficient environment30. Dinoflagellates can efficiently grow using a wide range of phosphate-containing organic molecules such as ATP, cytidine 5’-monophosphate, fructose-6-phosphate, glucose6-phosphate, glycerophosphate, uridine 5’-monophosphate, phenyl phosphate, RNA, etc.10,31,32. The key enzyme that allows the acquisition of Pi from phosphoesters is cell surface alkaline phosphatase (AP); in dinoflagellates this protein refers to the PhoAaty type33. Previous studies have shown that the activity of AP is enhanced under phosphorus deficiency in P. cordatum12,34. However, our transcriptome analysis did not reveal significant changes in the expression level of the gene coding for this enzyme. A similar phenomenon has been observed in other dinoflagellate species, namely Karenia brevis and Alexandrium catenella. It was shown that in these microorganisms, AP activity increased 6–7 times under phosphorus limitation, while no changes in the transcription were detected9,35,36. We suggest that in these cases, the expression of AP can be regulated on translational level, since it was shown for many other genes in dinoflagellates37. Another enzyme involved in the phosphate acquisition from the organic source in the phytoplankton is 5’-nucleotidase (5NT). For example, in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum, the mechanism of phosphate assimilation from ATP and glucose-6-phosphate has been shown to depend on different enzymes, 5NT and AP, respectively38. K. mikimotoi also shows an increase in 5NT content, but not AP-coding gene expression in the presence of ATP in the medium39. Several 5NT homologues were found in the P. cordatum transcriptome, and the expression of one of them was enhanced under phosphorus deprivation.

SPX domain-containing proteins play a crucial role in sensing external and internal Pi concentration and regulating Pi homeostasis in higher plants40. These proteins are widely distributed among various groups in phytoplankton and are apparently also involved in controlling Pi uptake41. Increased expression of genes coding for three SPX domain-containing proteins was detected in P-deprived P. cordatum cells. One of these proteins (CAK0815579.1) is highly homologous to VTC4, a subunit of the vacuole transporter chaperone (VTC) complex of S. cerevisiae. In yeasts, this protein synthesizes inorganic polyphosphate (polyP) chains from ATP and releases ADP42. This mechanism has been predicted to be conserved in eukaryotic microalga43. The upregulation of the gene VTC4 under phosphorus depletion has also been shown for the closely related dinoflagellate P. shikokuense and the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana11,44. These data suggest that polyP cycling is important for P-deprived systems. Another SPX domain-containing protein, CAK0866494.1, also contains predicted VTC1 domain and SMC domains; however, its function cannot be predicted due to its low homology with all characterized proteins in the NCBI database. The third protein, CAK0857988.1, contains only the SPX domain as a functional unit. A similar protein was described in P. tricornutum, where it has been shown to be a negative regulator of phosphate uptake under P-stress41. Therefore, in P. cordatum, this SPX domain containing protein may play a similar role. Notably, we also detected one down-regulated DEG encoding an SPX domain-containing protein; however, the low degree of homology and non-specificity of the domain hit prevented us from making any assumptions regarding its functions.

Finally, transcriptomic analysis of P. cordatum cells grown under deficiency of external sources of phosphorus revealed six DEGs with increased expression, encoding homologues of meiosis-associated proteins: RAD51, SPO11, RAD21/REC8-like protein, EXO1, MSH4, and MSH5. These proteins are responsible for processing of DSBs and meiotic recombination. Together with the increase in the proportion of 2C cells, this may indicate that by the 14th day of the experiment, a portion of the cells switches from the vegetative phase to the sexual phase of the life cycle. In this case, following the supply of nutrients, subsequent meiotic division can occur rapidly, as indicated by the changes in ploidy to 4С that we observed earlier21. Phosphate deprivation has been shown to induce a transition to the sexual process, for example, in Alexandrium minutum16 and A. tamarense17, however, mentions of DEGs associated with meiosis are virtually absent in studies on the transcriptomic response of dinoflagellates to such conditions. Meng and co-authors18 described genes in A. minutum cells subjected to nitrogen and phosphorus stress that showed altered expression and are homologous to those related to sex determination, mating, and fertilization. Nevertheless, none of these genes are associated with syngamy, recombination, or zygote division.

Meiotic division and increased expression of meiosis-associated genes can be related to the germination of resting cysts in dinoflagellates, which is considered a “sex for encystment” scenario45. The orthologues of DMC1, SPO11 and some genes encoding MEI-like proteins were up-regulated in the mature resting cysts of Scrippsiella acuminata (syn. S. trochoidea)46. The genes encoding SPO11, DMC1, MSH4, HOP2, MND1, and numerous MEI2-like proteins were up-regulated already during the germination of S. acuminata cysts45. In P. cordatum, resting cysts/hypnozygotes have not been described so far, and we did not observe them during our investigations. An alternative encystment-independent pathway of sexual reproduction was designated by Lin with co-authors45 as “sex for proliferation”, which may boost or sustain blooms. They have documented increased expression of some meiosis-associated genes, including RAD51, SPO11, EXO1, and RAD21/REC8-like in metatranscriptomic analyses of samples taken from natural blooming populations of P. shikokuense and K. mikimotoi45. This expression profile was supported by alterations in relative DNA content in cells, indicating the possibility of meiosis45. To some extent, the pathway we observed in P. cordatum may resemble an extension of the “sex for proliferation” scenario. In this hypothetical variant, a decrease in phosphate concentration during blooming – which has been mentioned in some studies47,48 – could serve as a trigger for the transition to the sexual process.

The role of MEI2-like proteins – homologues of MEI2 that is crucial for the switch to meiosis in yeasts49 – in dinoflagellates is the subject of a separate study. Lin with co-authors7 described MEI2-like genes that are sharply down-regulated in F. kawagutii under P-depleted conditions. We identified two MEI2-like DEGs, with one being up-regulated and the other down-regulated.

It should also be mentioned here that dinoflagellates can demonstrate unusual shifts in ploidy. In the blooming population of K. mikimotoi, 16-fold changes in relative DNA content were detected45; multiple rounds of replication without division (endoreduplication) have been suggested as one of possible routes in the life cycle of A. minutum16. In this context, the double and quadruple changes in nuclear DNA content that we observed in P. cordatum can be explained not only by sexual reproduction, but also by endoreduplication. We can deal with reversible polyploidy, as when nutrients are added, the cells return to their initial haploid stage. Indeed, RAD51 and SPO11 have been found to be expressed in somatic cells, e.g. plant tissues, aneuploid cancer cells, and to be involved in non-meiotic recombination50,51,52. Nevertheless, we identified up-regulated DEGs encoding homologues of MSH4 and MSH5 proteins that seem to specifically facilitate crossovers between homologous chromosomes during meiosis. Thus, transcriptomic analysis of P. cordatum provides evidence that deficiency of external sources of phosphorus can induce transition to the sexual phase of the life cycle in these dinoflagellates.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and experimental design

The clonal culture of Prorocentrum cordatum, strain CCAP1136/16 (from The Culture Collection of Algae and Protozoa, UK) was maintained in artificial seawater-based f/2 medium53 containing no silicate at salinity of 25. The medium was sterilized by autoclaving; the vitamin mixture was sterilized by sterile filtration and added separately. The batch cultures were grown under a 12 h light:12 h dark cycle (light period from 09 a.m. to 09 p.m.) at 100 µmol photons m-2 s-1 and 18 °C. The culture was unialgal but non-axenic; nevertheless, ampicillin was periodically added to the batch cultures to suppress bacterial growth.

To set up the experiment, we used a protocol previously developed to study the effect of nutrient deficiency on P. cordatum life cycle21. The initial culture (200 mL, replete f/2 medium with 880 µM NO3– and 40 µM PO43–, cell concentration of 3 × 104 cells mL-1) was grown for 7 d to reach a cell concentration of ~ 105 cells mL-1. It was then kept in the dark for 72 h for synchronization of the cell cycle. Next, cells from the initial culture were inoculated into two flasks at a concentration of 3 × 104 cell mL-1. In one of the flasks, the culture was diluted with the replete f/2 medium containing 880 µM NO3– and 40 µM PO43– (control culture), in the other one – with f/2 medium without added PO43– (P-limited culture, “–P”). These experimental cultures were grown for 14 d. Samples for measuring cell and phosphate concentrations, as well as for flow cytometry, were taken at 05:00 a.m. (during the dark period) on the day the experiment began (day 0), and then on days 3, 6, 9, 12, and 14. Cells for RNA extraction and sequencing were sampled also at 05:00 a.m. on day 14. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

Cell concentration was estimated using the Countess II FL Automated Cell Counter (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) or a Fuchs-Rosenthal counting chamber and light microscope. To control for the concentration of phosphate, a 1.8 mL sample was filtered through a 0.22-µm pore cellulose acetate syringe filter (C0000301, ALWSCI Technologies, China). Phosphate concentration was determined spectrophotometrically according to protocol described by Pote and Daniel54.

Flow cytometry

The 5-mL samples were concentrated by centrifugation (3000 g for 3 min). The cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 40 min, rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 100 mM glycine for 10 min, and then incubated in 96% ethanol at -20 °C for at least 24 h for pigment extraction. Before the analysis, samples were washed three times in PBS and incubated with 0.25 mg mL-1 RNase A and 0.05 mg mL-1 propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at room temperature for at least 30 min. The samples were analyzed using CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, USA, 488 nm laser) and CytExpert software v.2.6 (Beckman Coulter, USA). At least 5,000 cells (nuclei) were recorded for each sample.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using R version 4.3.355. The significance of differences in cell concentration and the fraction of cells with a relative DNA content of 2C between cultivation conditions and days of experiment was assessed with the help of the mixed-design ANOVA utilizing the rstatix package v.0.7.256. To perform pairwise comparisons between groups, we used the emmeans package v.1.11.057. The statistical significance level for all tests was set at α = 0.05.

RNA extraction and sequencing

For RNA isolation, approximately 3 × 106 cells from each experimental culture were harvested by centrifugation at 4500 g for 3 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C until processing. Initially, we attempted to apply a standard acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform (AGPC) protocol of total RNA extraction utilizing TRIzol reagent and its various analogues. However, this approach turned out to be non-optimal as the resulting RNA solution was heavily contaminated with starch (the presence of starch in the samples was tested by Lugol’s iodine solution). The cytoplasm of dinoflagellates contains numerous starch grains, and this polysaccharide tends to co-precipitate with the RNA pellet, hindering the effective dissolution of RNA58. This issue has been discussed in the context of plants and various algae, with different approaches compared and proposed e.g., 58,59,60,61,62. We have also tested several methods and finally we propose a modified protocol optimal for RNA isolation from dinoflagellate cells.

A lysis buffer was prepared according to the composition, designed by Li with co-authors63: 1% (w/v) SDS, 400 mM NaCl, and 20 mM EDTA in 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0). Before use, the buffer was sterilized by filtering through a syringe filter and then β-mercaptoethanol was added to achieve a final concentration of 1%. The ratio of buffer volume to sample volume was 1:10 (700 µl per sample). Cells, resuspended in lysis buffer, were subjected to a high-speed beating with 1.0 mm glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich) in a FastPrep-24 homogenizer (MP Biomedicals, USA) to disrupt thecal plates. The homogenization consisted of 4 cycles, each comprising 15 s of beating at a speed of 5 m/s and 15 s of pause. Then we again followed the protocol of extraction proposed by Li with co-authors63: the lysate was mixed with 0.3 volumes of saturated NaCl solution, shaken for 60 s and centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min. However, instead of phenol-chloroform extraction, we opted for an isolation and purification of total RNA on silica columns. For this, HiPure Plant RNA Kit (R415102 Magen, China) was utilized. We skipped points 1–3 of the manufacturer’s protocol regarding cell lysing; the upper 80% of supernatant from the previous step (centrifugation after treatment with NaCl solution) was transferred directly to a HiPure DNA column. Further RNA extraction process was conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted RNA was treated with DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The integrity of RNA samples was assessed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. The purity of the samples was determined using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

The RNA concentration was quantified using a Qubit 4 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and the RNA integrity was assessed using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, USA). Total RNA (100 ng) from each sample was used to prepare RNA libraries. The RIN values were < 5; however, for sequencing, we selected samples with clearly visible ribosomal rRNA bands. In this case, the TruSeq Stranded Total RNA with Ribo-Zero Plant kit (Illumina, USA) was effectively utilized for RNA sequencing library preparation. This kit enables rapid and specific removal of ribosomal RNA from samples. According to the species compatibility details provided by the manufacturer, in silico testing has predicted the removal of 18S and 28S rRNA for P. cordatum (https://www.illumina.com/products/selection-tools/truseq-total-rna-species-compatibility.html). The sequencing libraries were prepared following the manufacturer’s recommendations. The quality of the libraries was assessed using the Bioanalyzer system. The library preparations were sequenced using an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform, generating 2 × 101 bp paired-end reads.

Sequence assembly

Demultiplexing of the sequencing reads was performed with Illumina bcl2fastq (version 2.20), adapters were trimmed with Skewer (version 0.2.2)64. Quality checking of the reads was conducted using FastQC v0.11.565 and the low-quality bases were clipped by Trimmomatic v0.3966 with the options “SLIDINGWINDOW:4:20 MINLEN:50”. After that the remaining trimmed reads were mapped to the genomic assembly of Prorocentrum cordatum CCMP1329 (NCBI Assembly ID GCA_963575745.1)22 using STAR alignment tool (v2.7.11b)67. The locus IDs, coding sequence (CDS) IDs, and protein IDs presented in our work were provided in accordance with the assembly dataset. The read counts for the genes were obtained using htseq-count v2.0.268 with the options “-t gene -f bam -r pos -s no --secondary-alignments ignore --supplementary-alignments ignore”.

Analysis of differentially expressed genes

The differentially expressed genes were evaluated using DESeq269. The p-values were corrected to control the false discovery rate (FDR). The genes with |log2(fold change)| > 1 (fold change > 2 or < 0.5) and the corrected p-values (padj) < 0.05 cutoff were assigned as differentially expressed genes (DEGs). The results of the differential expression analysis were plotted using VolcaNoseR web app70. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using built-in prcomp function in R (version 3.0.3)55. The DEGs with |log2(fold change)| higher than 1 were annotated using Diamond v2.1.8 and NR NCBI database with the cutoff for the maximal e-value set to 10–5. Besides, annotation was conducted using SMA3s v2.171 with settings “-id1 30 -id2 30 -cov1 50 -cov2 50”. For unclassified hits we also performed blastp search (with e-value threshold e-10) against reference proteomes set in the public database UniProt (release 2024_02)28. Blast2GO 6.0.3 and OmicsBox 3.2 software was used for additional analysis of DEGs (blastp-fast and blastp-sensitive search in NCBI database with e-value < e–10 cut-off and “Polarella” exclusion filter for taxa) and for assignment Gene Ontology terms describing biological processes, molecular function, and cellular component72. The DEGs were also matched by local blast to the sequences of Polarella glacialis reference proteome (UP000654075), which in turn were then used for functional classification in PANTHER (release 18.0)73. For the manual verification of homologues, we search for conserved domains and motifs using the CD-Search NCBI tool against the CDD v3.21–62,456 PSSMs database74 and the InterProScan web tool75.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study that are not included in the article or Supplementary Information files are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The reference genomic assembly of Prorocentrum cordatum CCMP1329 (GCA_963575745.1) and related data are available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCA_963575745.1/). The reference proteome of Polarella glacialis (UP000654075) used in the analysis is available from the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/proteomes/UP000654075).

References

Paytan, A. & McLaughlin, K. The oceanic phosphorus cycle. Chem. Rev. 107, 563–576 (2007).

Cooper, G. M. The Cell: A Molecular Approach (Sinauer Associates, 2000).

Lin, S., Litaker, R. W. & Sunda, W. G. Phosphorus physiological ecology and molecular mechanisms in marine phytoplankton. J. Phycol. 52, 10–36 (2016).

Moore, C. M. et al. Processes and patterns of oceanic nutrient limitation. Nat. Geosci. 6, 701–710 (2013).

Moon, J. Y. et al. Anthropogenic nitrogen is changing the East China and yellow seas from being N deficient to being P deficient. Limnol. Oceanogr. 66, 914–924 (2021).

Stoecker, D. K., Hansen, P. J., Caron, D. A. & Mitra, A. Mixotrophy in the marine plankton. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 9, 311–335 (2017).

Lin, S., Yu, L. & Zhang, H. Transcriptomic responses to thermal stress and varied phosphorus conditions in Fugacium Kawagutii Microorganisms 7, 96 (2019).

Zhang, S. F., Yuan, C. J., Chen, Y., Lin, L. & Wang, D. Z. Transcriptomic response to changing ambient phosphorus in the marine dinoflagellate Prorocentrum Donghaiense. Sci. Total Environ. 692, 1037–1047 (2019).

Morey, J. S. et al. Transcriptomic response of the red tide dinoflagellate, Karenia brevis, to nitrogen and phosphorus depletion and addition. BMC Genom. 12, 346 (2011).

Li, M., Li, L., Shi, X., Lin, L. & Lin, S. Effects of phosphorus deficiency and adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) on growth and cell cycle of the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum Donghaiense. Harmful Algae. 47, 35–41 (2015).

Shi, X. et al. Transcriptomic and MicroRNAomic profiling reveals multi-faceted mechanisms to Cope with phosphate stress in a dinoflagellate. ISME J. 11, 2209–2218 (2017).

Dyhrman, S. T. & Palenik, B. Phosphate stress in cultures and field populations of the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum detected by a single-cell alkaline phosphatase assay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 3205–3212 (1999).

Harke, M. J., Juhl, A. R., Haley, S. T., Alexander, H. & Dyhrman, S. T. Conserved transcriptional responses to nutrient stress in bloom-forming algae. Front. Microbiol. 8, (2017).

Johnson, M. D. Inducible mixotrophy in the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 62, 431–443 (2015).

Huang, X., Zhuang, Y., Xiong, Y., Li, D. & Ou, L. Efficient modulation of cellular phosphorus components in response to phosphorus deficiency in the dinoflagellate Karenia Mikimotoi Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 89, e00867–e00823 (2023).

Figueroa, R. I., Dapena, C., Bravo, I. & Cuadrado, A. The hidden sexuality of Alexandrium minutum: An example of overlooked sex in dinoflagellates. PLoS One 10, 1–21 (2015).

Anderson, D. M. & Lindquist, N. L. Time-course measurements of phosphorus depletion and cyst formation in the dinoflagellate Gonyaulax tamarensis Lebour. J. Exp. Mar. Bio Ecol. 86, 1–13 (1985).

Meng, F. Q., Song, J. T., Zhou, J. & Cai, Z. H. Transcriptomic profile and sexual reproduction-relevant genes of Alexandrium minutum in response to nutritional deficiency. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1–16 (2019).

Blackburn, S. I., Hallegraeff, G. M. & Bolch, C. J. Vegetative reproduction and sexual life cycle of the toxic dinoflagellate Gymnodinium Catenatum from Tasmania, Australia. J. Phycol. 25, 577–590 (1989).

Figueroa, R. I., Vázquez, J. A., Massanet, A., Murado, M. A. & Bravo, I. Interactive effects of salinity and temperature on planozygote and cyst formation of Alexandrium minutum (Dinophyceae) in culture. J. Phycol. 47, 13–24 (2011).

Kalinina, V., Berdieva, M., Aksenov, N. & Skarlato, S. Phosphorus deficiency induces sexual reproduction in the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum cordatum. Sci. Rep. 13, 14191 (2023).

Dougan, K. E. et al. Multi-omics analysis reveals the molecular response to heat stress in a red tide dinoflagellate. Genome Biol. 24, 265 (2023).

Zhang, J., Li, X., Wang, X. & Guan, W. Transcriptome analysis of two bloom-forming Prorocentrum species reveals physiological changes related to light and temperature. Harmful Algae 125, 102421 (2023).

Wikfors, G. H. & Fernandez, E. Induced bacteriovory in a declining culture of the mixotrophic dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum (pavillard) schiller. Int. J. Ecol. 1–5 (2013).

Shi, Y., Liu, M., Ding, W. & Liu, J. Novel insights into phosphorus deprivation boosted lipid synthesis in the marine Alga Nannochloropsis oceanica without compromising biomass production. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68, 11488–11502 (2020).

Wang, X., Huang, B. & Zhang, H. Phosphorus deficiency affects multiple macromolecular biosynthesis pathways of Thalassiosira weissflogii. Acta Oceanol. Sin 33, 85–91 (2014).

Li, D. W., Tan, J. Z., Li, Z. F. & Ou, L. J. Membrane lipid remodeling and autophagy to cope with phosphorus deficiency in the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum Shikokuense Chemosphere 349, 140844 (2024).

Bateman, A. et al. UniProt: The universal protein knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D523–D531 (2023).

Samyn, D. R., Van Der Veken, J., Van Zeebroeck, G., Persson, B. L. & Karlsson, B. C. Key residues and phosphate release routes in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Pho84 transceptor: The role of TYR179 in functional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 26388–26398 (2016).

Huang, K. et al. Phosphomonoesterase and phosphodiesterase activities and their regulation during dinoflagellate blooms under different external phosphate conditions. Mar. Ecol. Prog Ser. 698, 41–54 (2022).

Huang, B., Ou, L., Hong, H., Luo, H. & Wang, D. Bioavailability of dissolved organic phosphorus compounds to typical harmful dinoflagellate Prorocentrum Donghaiense Lu. Mar. Pollut Bull. 51, 838–844 (2005).

Oh, S. J., Kwon, H. K., Noh, I. H. & Yang, H. S. Dissolved organic phosphorus utilization and alkaline phosphatase activity of the dinoflagellate Gymnodinium impudicum isolated from the South sea of Korea. Ocean. Sci. J. 45, 171–178 (2010).

Lin, X., Wang, L., Shi, X. & Lin, S. Rapidly diverging evolution of an atypical alkaline phosphatase (PhoAaty) in marine phytoplankton: insights from dinoflagellate alkaline phosphatases. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1–12 (2015).

Dyhrman, S. T. & Palenik, B. A single-cell immunoassay for phosphate stress in the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum minimum (Dinophyceae). J. Phycol. 37, 400–410 (2001).

Lin, X., Zhang, H., Huang, B. & Lin, S. Alkaline phosphatase gene sequence characteristics and transcriptional regulation by phosphate limitation in Karenia brevis (Dinophyceae). Harmful Algae. 17, 14–24 (2012).

Zhang, C. et al. Suppression Subtraction hybridization analysis revealed regulation of some cell cycle and toxin genes in Alexandrium catenella by phosphate limitation. Harmful Algae. 39, 26–39 (2014).

Roy, S., Jagus, R. & Morse, D. Translation and translational control in dinoflagellates. Microorganisms 6, 30 (2018).

Zhang, X. et al. Transcriptomics and physiological analyses unveil the distinct mechanisms of ATP and glucose-6-phosphate utilization in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Front. Mar. Sci. 10, 1–11 (2023).

Luo, H. et al. Transcriptomic and physiological analyses of the dinoflagellate Karenia Mikimotoi reveal non-alkaline phosphatase-based molecular machinery of ATP utilisation. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 4506–4518 (2017).

Zhou, Z. et al. SPX proteins regulate Pi homeostasis and signaling in different subcellular level. Plant. Signal. Behav. 10, e1061163 (2015).

Zhang, K. et al. SPX-related genes regulate phosphorus homeostasis in the marine phytoplankton, Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Commun. Biol. 4, 797 (2021).

Hothorn, M. et al. Catalytic core of amembrane-associated eukaryotic polyphosphate polymerase. Sci. (80-). 324, 513–516 (2009).

Cliff, A. et al. Polyphosphate synthesis is an evolutionarily ancient phosphorus storage strategy in microalgae. Algal Res. 73, 103161 (2023).

Dyhrman, S. T. et al. The transcriptome and proteome of the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana reveal a diverse phosphorus stress response. PLoS One 7, e33768 (2012).

Lin, S. et al. Active meiosis during dinoflagellate blooms: A ‘ sex for proliferation ’ hypothesis. Harmful Algae 118, 102307 (2022).

Deng, Y., Hu, Z., Shang, L., Peng, Q. & Tang, Y. Z. Transcriptomic analyses of Scrippsiella trochoidea reveals processes regulating encystment and dormancy in the life cycle of a dinoflagellate, with a particular attention to the role of abscisic acid. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1–19 (2017).

Li, J., Glibert, P. M., Zhou, M., Lu, S. & Lu, D. Relationships between nitrogen and phosphorus forms and ratios and the development of dinoflagellate blooms in the East China sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog Ser. 383, 11–26 (2009).

Zhang, Y. et al. Metatranscriptomic signatures associated with phytoplankton regime shift from diatom dominance to a dinoflagellate bloom. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1–13 (2019).

Watanabe, Y. & Yamamoto, M. S. pombe mei2 + encodes an RNA-binding protein essential for premeiotic DNA synthesis and meiosis I, which cooperates with a novel RNA species meiRNA. Cell 78, 487–498 (1994).

Salmina, K. et al. The cancer aneuploidy paradox: in the light of evolution. Genes (Basel) 10, (2019).

Keeney, S. Mechanism and control of meiotic recombination initiation. in Current Topics in Developmental Biology (ed Schatten, G.) vol 52 1–53 (Academic, (2001).

Da Ines, O. et al. Effects of XRCC2 and RAD51B mutations on somatic and meiotic recombination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant. J. 74, 959–970 (2013).

Guillard, R. R. L. & Ryther, J. H. Studies of marine planktonic diatoms. I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt, and Detonula confervacea (Cleve) Gran. Can. J. Microbiol. 8, 229–239 (1962).

Pote, D. H. & Daniel, T. C. Dissolved phosphorus in water samples. in Methods of Phosphorus Analysis for Soils, Sediments, Residuals, and Waters (eds. Kovar, J. L. & Pierzynski, J. M.) 110–112 (Virginia Tech University, 2009).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (2024).

Kassambara, A. rstatix: Pipe-friendly framework for basic statistical tests. CRAN: Contributed Packages https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.rstatix (2019).

Lenth, R. V. & emmeans Estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. CRAN: Contributed Packages https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.emmeans (2017).

Li, Z. & Trick, H. N. Rapid method for high-quality RNA isolation from seed endosperm containing high levels of starch. Biotechniques 38, 872–876 (2005).

Dutta, S., Muthusamy, V., Chhabra, R., Zunjare, R. U. & Hossain, F. Two-step method for isolation of high-quality RNA from stored seeds of maize rich in starch. 3 Biotech. 10, 1–8 (2020).

Jensen, T. et al. Optimised protocols for RNA extraction from a broad taxonomic range of algae. J. Appl. Phycol. 35, 1743–1753 (2023).

Mundt, F., Heinrich, S. & Hanelt, D. RNA isolation from taxonomically diverse photosynthetic protists. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 17, 190–199 (2019).

Yan, W. J., Pendi, F. H. & Hussain, H. Improved CTAB method for RNA extraction of thick waxy leaf tissues from Sago palm (Metroxylon Sagu Rottb). Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 9, 1–14 (2022).

Li, J. H. et al. A simple, rapid and effective method for total RNA extraction from Lentinula Edodes. Biotechnol. Lett. 28, 1193–1197 (2006).

Jiang, H., Lei, R., Ding, S. W. & Zhu, S. Skewer: a fast and accurate adapter trimmer for next-generation sequencing paired-end reads. BMC Bioinform. 15, 182 (2014).

Andrews, S. FastQC: A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. (2010). http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T. & Huber, W. HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169 (2015).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Goedhart, J. & Luijsterburg, M. S. VolcaNoseR is a web app for creating, exploring, labeling and sharing volcano plots. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–5 (2020).

Casimiro-Soriguer, C. S., Muñoz‐Mérida, A. & Pérez‐Pulido, A. J. Sma3s: A universal tool for easy functional annotation of proteomes and transcriptomes. Proteomics 17 (2017).

Götz, S. et al. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 3420–3435 (2008).

Thomas, P. D. et al. Making genome-scale phylogenetics accessible to all. Protein Sci. 31, 8–22 (2022).

Lu, S. et al. CDD/SPARCLE: The conserved domain database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D265–D268 (2020).

Paysan-Lafosse, T. et al. InterPro in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D418–D427 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Russian Science Foundation, project 22–74-10097. Libraries preparation, RNA sequencing, assembly and primary analysis services were provided by ALGAVITAPRO Ltd., Moscow, Russia (official distributor of CeGat GmbH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.K., M.B., and S.S. designed research, O.P. and M.B. conducted experiments, V.K., M.B., and P.S. performed data analysis, V.K., P.S., S.S., and M.B. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kalinina, V., Palii, O., Safonov, P. et al. Transcriptomic response of marine dinoflagellate Prorocentrum cordatum to phosphorus deficiency. Sci Rep 15, 18797 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02014-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02014-x