Abstract

The study aimed to investigate whether eosinophil major basic protein (MBP), which is linked to cataract formation due to lens epithelial cell (LEC) damage in atopic dermatitis (AD), is associated with intraocular lens (IOL) dislocation. This retrospective observational study was conducted at a Medical University Hospital and included 22 eyes (10 AD, 12 non-AD [NAD]) that underwent IOL explantation and fixation. Surgeries were conducted to extract the intraocular lens capsule for morphological evaluations. Quantitative analysis of the MBP staining was conducted using the staining area ratio (SAR) gap. MBP staining was negative in all cases for both the lens capsule and LEC. The SAR gap in Soemmering’s ring was significantly higher in the AD group (14.3 ± 8.7%) than in the NAD group (1.1 ± 1.1%) (p = 0.0037). In contrast, the SAR gap for fibrous metaplasia showed no significant difference between the AD (8.3 ± 13.2%) and NAD (6.5 ± 12.3%) groups (p = 0.75). Six cases of fibrous metaplasia, including those in the NAD group, showed SAR gaps equal to or greater than those in the positive control group, with five classified as low-density fibrosis (LDF). While Soemmering’s rings in AD cases demonstrated greater MBP immunoreactivity than NAD controls, both groups exhibited MBP-positive fibrous metaplasia specimens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intraocular lens (IOL) dislocation can occur months to years after cataract surgery. The annual incidence of IOL dislocation is less than 0.05%, and the cumulative incidence over 10–25 years is approximately 0.1–3%1. Advances in cataract surgery have enabled IOL insertion into the capsular bag, even in cases where the zonule is weak, which was previously considered challenging2. Consequently, the number of IOL dislocation cases may increase in the future. The risk factors for IOL dislocation include cataract surgery in patients with a history of ocular trauma, vitrectomy, pseudoexfoliation syndrome, retinitis pigmentosa, high myopia, uveitis, and atopic dermatitis (AD)1. The prevalence of AD in developed countries has increased two- to threefold in recent decades3. AD can cause various ocular complications, such as cataracts, retinal detachment, glaucoma, conjunctivitis, and keratoconus, which significantly impair vision, particularly in younger individuals4,5. Notably, IOL dislocation in patients with AD can result not only from capsular bag dislocation (CBD) caused by zonular rupture due to scratching and rubbing associated with ocular itching, but also from dead bag syndrome (DBS), due to a very clear bag many years postoperatively, without fibrotic changes or proliferative material within the bag6,7. The reasons for these differences in the dislocation form remain unclear.

We observed morphological abnormalities in lens epithelial cells (LECs) and insufficient fibrosis of the lens capsule in patients with AD-associated IOL dislocations. Furthermore, we reported a high incidence of capsular splitting, a pathological feature characteristic of DBS, regardless of the dislocation type in AD cases8, suggesting that AD may be a contributing factor to previously unexplained DBS9. LEC damage caused by eosinophil major basic protein (MBP), which is present in high concentration in the aqueous humor of patients with AD, has been implicated as a cause of cataracts in patients with AD10,11. We investigated whether MBP is associated with the pathological features of AD-related IOL dislocation.

To test this hypothesis, we conducted MBP immunostaining on the extracted capsular bags in cases of IOL dislocation in AD and non-AD (NAD) cases and examined the involvement of MBP in AD-associated IOL dislocation.

Results

The AD group comprised 10 patients (10 eyes) (Male, n = 9; mean age, 47.0 ± 10.3 years). One eye had a history of trauma, two eyes had a history of vitrectomy, and one eye had a history of uveitis. The IOL dislocation types included seven eyes with CBD and three eyes with DBS. The mean duration until IOL dislocation was 11.5 ± 5.6 years, and the mean axial length was 25.5 ± 1.4 mm (Table 1).

Twelve patients (12 eyes) were assigned to the NAD group (male, n = 10; mean age, 64.0 ± 13.8 years). Six eyes had a history of trauma, five eyes had a history of vitrectomy, and the cause was unknown in three eyes. All patients in the NAD group had CBD. The mean duration until IOL dislocation was 10.2 ± 5.7 years, and the mean axial length was 25.6 ± 1.5 mm (Table 2).

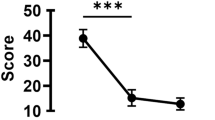

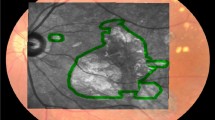

In MBP immunostaining, the SAR gap for the positive control was 12.7%. The SAR gap was 14.3 ± 8.7% in the AD group and 1.1 ± 1.1% in the NAD group, with the AD group showing a significantly higher SAR gap than that in the positive control group (p-value = 0.0037) (Fig. 1). For example, in the DBS case in the AD group (Case 2), MBP staining in the Soemmering’s ring was higher than that in the negative control (Fig. 2). Similarly, in the CBD case of the AD group (Case 9), the same trend was observed (Fig. 3). In contrast, in the CBD case of the NAD group (Case 12), MBP staining and the negative control showed similar staining levels (Fig. 4a, b).

Capsular bag dislocation case in the Non-Atopic Dermatitis group (Case 12). MBP staining of Soemmering’s ring (a) and the negative control in the same area (b). (a and b) show similar staining intensity. MBP staining of fibrous metaplasia (c) and the negative control in the same area (d). Compared to (d, c) shows similar staining intensity. MBP = major basic protein.

The SAR gap in fibrous metaplasia was 8.3 ± 13.2% in the AD group and 6.5 ± 12.3% in the NAD group, with both groups showing SAR gaps below that of the positive control; no significant difference was observed (p-value = 0.75) (Figs. 4c and d and 5). However, six cases of fibrous metaplasia, including those in the NAD group, showed an SAR gap ≥ 10%, equivalent to that of the positive control. Of these cases, five were classified as LDF (Tables 1 and 2).

Furthermore, the lens capsule and LEC were negative in all cases in both groups (Tables 1 and 2; Fig. 6).

Discussion

This study provides novel insights into the pathological characteristics of the lens capsule complex and its relationship with MBP in patients with AD-associated IOL dislocations. The AD group showed a significantly higher SAR gap in the Soemmering’s ring than the NAD group, confirming the MBP staining. These results suggest that, in the AD group, MBP may continue to contribute to the weakening of the lens capsule complex even after cataract surgery.

Several studies have reported the involvement of MBP toxicity in the development of AD-associated cataracts. Yokoi et al. measured MBP immunostaining in the lens capsule and LEC, as well as aqueous MBP concentrations in AD-associated cataracts and age-related cataracts. Several cases of AD-associated cataracts showed MBP adhesion to LEC and elevated aqueous MBP concentrations, while no such findings were observed in the age-related cataracts12. In contrast, Yamamoto et al. demonstrated in vivo that MBP detected in the aqueous humor of AD-associated cataracts originated from the patient’s plasma and established in vitro that MBP damages human LEC, proposing the hypothesis that MBP-induced LEC damage contributes to the mechanism of AD-associated cataracts10. Furthermore, MBP toxicity is suggested to be involved in the development of AD-related ocular complications other than cataracts. Matsuda et al. detected MBP in the aqueous humor of approximately half of the cases of AD-associated retinal detachment, while no MBP was detected in non-AD-associated retinal detachment, proposing the involvement of MBP in the development of AD-associated retinal detachment13. The involvement of MBP in AD-associated keratoconjunctivitis has also been reported14.

Based on these findings, we propose that LEC dysfunction due to LEC damage caused by MBP toxicity, termed “Lens Epitheliopathy,” may weaken the lens capsule, which normally forms the basement membrane produced by LEC. The LEC dysfunction may also result in inadequate fibrosis formation through epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) post-cataract surgery, contributing to the fragility of the lens capsule complex and IOL dislocation in patients with AD. In our initial report, we investigated the pathology of the lens capsule complex in cases of AD-associated IOL dislocation, reporting the fragility of the lens capsule, including capsular splitting and inadequate fibrosis formation8. Moreover, in IOL dislocation cases caused by DBS, where LECs are believed to be deficient or significantly reduced, immunostaining of the lens capsule complex revealed positive staining for fibrous components, such as type I collagen and fibronectin, which are produced during EMT, suggesting that even a small number of LECs may have remained post-cataract surgery and secreted fibrous components before disappearing15. These results suggest that LEC damage may continue after cataract surgery, which is consistent with MBP-related toxic damage.

This study identified the differences in MBP staining patterns across various ocular tissues. The AD group showed a higher SAR gap in the Soemmering’s ring and some fibrous metaplasia than the positive control, possibly because of cell density difference. High cell density inhibits antibody penetration, leading to reduced staining16. Soemmering’s ring has lower cell density compared to fibrous metaplasia, making it more permeable to MBP in cases where aqueous MBP concentration is elevated in AD.

In contrast, no MBP staining was observed in the Soemmering’s ring in any of the patients with NAD. However, three cases (Cases 16, 20, and 21) showed an SAR gap in fibrous metaplasia equivalent to that in the positive control, with histories of trauma and unknown etiology. Additionally, two of the three cases exhibited LDF, a characteristic feature of AD8. Although AD was classified based on patient self-reporting in this study, these two cases were likely predisposed to AD. Future studies should use biomarkers and clinical diagnoses to confirm the presence of AD.

Additionally, no MBP was detected in the lens capsule. The lens is an avascular tissue, and nutrients are supplied to the LEC through the anterior capsule. The anterior capsule facilitates passive transport, which is influenced by the molecular size of the product. Larger molecules, such as dextran, composed of the polysaccharide glucose (500 kDa), do not pass through the anterior capsule, but MBP, with a molecular weight of 13.8 kDa, is small enough to pass through10, suggesting that MBP may not have been detected because of the sensitivity limitations of the immunostaining method. While MBP in the lens capsule may exist at the protein level, more sensitive methods, such as immunoelectron microscopy, are needed for detection.

LECs in AD-associated cataracts have been reported to be positive for MBP10. However, in this study, LECs in AD-associated IOL dislocation cases were negative for MBP. The anterior capsule was extensively removed during the initial cataract surgery, which significantly reduced the number of LECs. It is plausible that the remaining LECs in the open capsule were further exposed to MBP due to aqueous inflow, leading to accelerated cell degeneration or reduction, which may explain the lower staining observed in this study8.

Patients with AD have elevated serum MBP levels, and when the blood-aqueous barrier is compromised, aqueous MBP concentration increases, leading to LEC damage and development of specific types of cataracts at a young age17. Since the severity of AD varies from case to case, the risk and pathology of IOL dislocation may differ individually. Depending on the aqueous MBP concentration and the extent of mechanical irritation from rubbing, either zonular weakening or capsular fragility at the zonular attachment site may dominate, resulting in CBD, or overall capsular fragility may lead to DBS8,18. Future investigations are needed to examine whether differences in MBP concentrations in the blood, aqueous humor, and vitreous humor of patients with AD are related to the mechanism of IOL dislocation. In the future, MBP biomarkers may help identify patients at high risk of IOL dislocation, enabling interventions such as controlling MBP levels in the blood and aqueous humor with medication or surgical operation that avoids IOL insertion into the capsule during initial cataract surgery, potentially preventing IOL dislocation in patients with AD.

This study has several limitations. First, our small sample—particularly sparse DBS cases—limits generalizability. Second, while we standardized IHC protocols, the absence of aqueous MBP levels leaves open questions about systemic vs. local protein dynamics. Third, the cross-sectional design cannot establish whether MBP deposition precedes or results from dislocation.

To the best of our knowledge, this study provides novel insights into the pathological characteristics of the lens capsule in AD-associated IOL dislocation and its relationship with MBP. Compared with the NAD group, the AD group showed a higher incidence of MBP positivity in the Soemmering’s ring. These findings suggest that MBP may potentially contribute to the unique fragility of the lens capsule, even after cataract surgery, in patients with AD.

Methods

Ethical approval

This case series was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jikei University School of Medicine and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (approval number: 35–057[11680]). This study did not involve any invasive or interventional procedures and used only existing samples and information.

Patient consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from the participants using an opt-out method, in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects (Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare). Documents approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jikei University School of Medicine were posted on the university’s website, and the information for this research was announced on the hospital’s bulletin board. All participants had the right to refuse participation at any time (opt-out method).

Study setting and data sources

This study was conducted between November 2022 and June 2023 in the Department of Ophthalmology, Jikei Medical University Hospital, Tokyo. The study participants corresponded to cases previously reported in a peer-reviewed journal, where we described findings based only on hematoxylin & eosin and Masson’s trichrome staining8.

This study included patients with IOL dislocation who underwent IOL extraction. In particular, only the cases in which the extracted lens bag was appropriately processed as a specimen were included. Based on the slit-lamp examination and intraoperative findings, IOL dislocations were classified as CBD or DBS. Specifically, dislocations in which the IOL remained within the capsular bag and formed a complex with the capsule were classified as CBD. Cases in which the crystalline lens capsule was intact at the time of the initial cataract surgery, but subsequently ruptured, leading to IOL dislocation without an accompanying capsular bag, were classified as DBS. Patient data on age, sex, history of prior intraocular surgery, eye axial length, AD, history of trauma, pseudoexfoliation syndrome, uveitis, and the presence or absence of retinitis pigmentosa were extracted from the medical records. The participants were divided into an AD group with 10 eyes (10 patients) and a non-AD group with 12 eyes (12 patients).

Surgical technique8

Surgeries were performed by seven surgeons (three authors of this study). To extract the acrylic IOL, a small incision was made, and the IOL was either removed as a whole using IOL extraction forceps or fragmented using an IOL cutter19. An L-shaped scleral tunnel incision was made to remove the polymethyl methacrylate IOL20. In CBD cases, the lens bag was extracted simultaneously with the IOL. In DBS cases, after IOL extraction, the zonules were incised using a vitreous cutter and extracted.

Pathology specimen Preparation8

The lens capsule extracted during surgery was fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. After dehydration, it was embedded in paraffin, sectioned into 3-µm thick slices, and then stained with hematoxylin & eosin and Masson’s trichrome. The pathological evaluations were conducted by two ophthalmologists (two authors) and two pathologists (two authors). Morphological evaluations of the lens capsule, LEC, Soemmering’s ring, and fibrous metaplasia (distinguishing between high- and low-density fibrosis [LDF]) were also conducted. Additionally, MBP immunostaining was performed on these structures.

Immunohistochemical staining Method10

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lens capsule specimens were sectioned and blocked with endogenous peroxidase, followed by enzyme digestion using Proteinase K (S3020, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). After washing with PBS, blocking was performed using goat serum (426041; NICHIREI, Tokyo, Japan). The primary antibody used was a mouse anti-human eosinophil MBP antibody (1:200, BMK13, Bio-Rad, Oxford, UK), and the secondary antibody was Histofine Simple Stain MAX-PO-Multi (NICHIREI, Tokyo, Japan). For color development, 3,3’-Diaminobenzidine (DAB, 343–00901, Dojindo Laboratory, Kumamoto, Japan) was used.

For each specimen, mouse IgG1κ monoclonal antibody (ab170190, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used as an isotype control (negative control). An isotype control was used instead of the primary antibody and processed using the same protocol.

Immunohistochemical staining evaluation

Digital pathology images captured by the microscope slide scanner Aperio AT2 (Leica Biosystems) were magnified 40 x, and image regions were set at 300 × 300 pixels (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Quantitative evaluation of MBP immunostaining was performed using image analysis software ImageJ2 (version 2.14.0), based on methods from previous studies that employ RGB channel separation and red-channel thresholding, with reference to negative control slides21,22,23. To detect brown DAB coloration, the MBP-stained images were split into RGB (red-green-blue) channels, and the red channel was used to detect the stained areas, which were then highlighted in red (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Thresholds corresponding to specific staining areas were set, and the MBP staining area ratio (SAR) was measured. The same process was applied to the negative control images of the same regions, and the SAR of the negative control was measured (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d). Based on these results, the difference in SAR between the MBP and negative control was defined as the SAR gap and was compared between the two groups. Tissues from patients with eosinophilic esophagitis were used as a positive control, and the SAR gap was calculated under the same conditions (Supplementary Fig. 2). Due to sample size limitations, a quantitative evaluation of the lens capsule and LEC could not be performed. Instead, a qualitative assessment was performed by an ophthalmologist (one author) and pathologist (one author), who were blinded to the patients’ clinical history.

Statistical analysis for MBP immunostaining quantification

To quantify MBP immunostaining, statistical analysis was conducted using the SciPy library version 1.9.1 in the Python programming language. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the SAR gap between the AD and NAD groups. The results are visualized using boxplots displaying the median, interquartile range, and range of data. Additionally, the mean ± standard deviation of each group is included in the boxplots. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The data were visualized using Matplotlib version 3.5.1.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. E-mail: ymasuda@jikei.ac.jp 3-25-8 Nishi-Shimbashi, Minato-ku Tokyo, 105-8461, Japan TEL:+81-3-3433-1111.

References

Kristianslund, O., Dalby, M. & Drolsum, L. Late in-the-bag intraocular lens dislocation. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 47, 942–954 (2021).

Darian-Smith, E., Safran, S. G. & Coroneo, M. T. Zonular and capsular bag disorders: a hypothetical perspective based on recent pathophysiological insights. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 49, 207–212 (2023).

Nutten, S. Atopic dermatitis: global epidemiology and risk factors. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 66 (Supplement 1), 8–16 (2015).

Hsu, J. I., Pflugfelder, S. C. & Kim, S. J. Ocular complications of atopic dermatitis. Cutis 104, 189–193 (2019).

Pietruszyńska, M. et al. Ophthalmic manifestations of atopic dermatitis. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 37, 174–179 (2020).

Yamazaki, S., Nakamura, K. & Kurosaka, D. Intraocular lens subluxation in a patient with facial atopic dermatitis. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 27, 337–338 (2001).

Bassily, R., Lencova, A. & Rajan, M. S. Bilateral rupture of the posterior capsule and intraocular lens dislocation from excessive eye rubbing. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 42, 329–331 (2016).

Komatsu, K. et al. Lens capsule pathological characteristics in cases of intraocular lens dislocation with atopic dermatitis. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 50, 611–617 (2024).

Culp, C. et al. Clinical and histopathological findings in the dead bag syndrome. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 48, 177–184 (2022).

Yamamoto, N. et al. Mechanism of atopic cataract caused by eosinophil granule major basic protein. Med. Mol. Morphol. 53, 94–103 (2020).

Iida, M. et al. Lens thickness in atopic cataract: case-control study. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 49, 853–857 (2023).

Yokoi, N. et al. Association of eosinophil granule major basic protein with atopic cataract. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 122, 825–829 (1996).

Matsuda, H., Katsura, H., Ishida, S. & Inoue, M. Aqueous levels of eosinophil cationic protein and major basic protein in patients with retinal detachment associated with atopic dermatitis. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 102, 189–192 (1998).

Messmer, E. M., May, C. A., Stefani, F. H., Welge-Luessen, U. & Kampik, A. Toxic eosinophil granule protein deposition in corneal ulcerations and scars associated with atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 134, 816–821 (2002).

Sumioka, T. et al. Immunohistochemical findings of lens capsules obtained from patients with dead bag syndrome. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 50, 862–867 (2024).

Piña, R. et al. Ten approaches that improve immunostaining: a review of the latest advances for the optimization of Immunofluorescence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 1426 (2022).

Morita, H., Yamamoto, K. & Kitano, Y. Elevation of serum major basic protein in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Dermatol. Sci. 9, 165–168 (1995).

Hirata, A., Okinami, S. & Hayashi, K. Occurrence of capsular delamination in the dislocated in-the-bag intraocular lens. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 249, 1409–1415 (2011).

Fukuoka, S. et al. Intraocular lens extraction using the cartridge pull-through technique. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 47, e70–e74 (2021).

Ohta, T. & T-fixation technique L-shaped pocket incision for IOL dislocation. Rinsho Ganka. 73, 171–180 (2019). (in Japanese).

Vrekoussis, T. et al. Image analysis of breast cancer immunohistochemistry-stained sections using ImageJ: an RGB-based model. Anticancer Res. 29, 499–504 (2009).

Fu, R., Ma, X., Bian, Z. & Ma, J. Digital separation of diaminobenzidine-stained tissues via an automatic color-filtering for immunohistochemical quantification. Biomed. Opt. Express. 6, 544–558 (2015).

Patel, S., Fridovich-Keil, S., Rasmussen, S. A. & Fridovich-Keil, J. L. DAB-quant: A digital method for quantifying DAB immunohistochemistry. PLoS One. 17, e0271593 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients for their participation in this study. We express our deepest gratitude to Dr. Akira Watanabe, Dr. Shumpei Ogawa, Dr. Tomoyuki Watanabe, and Dr. Kokoro Konuma for their cooperation in providing the surgical specimens. We would also like to express our deepest gratitude to Dr. Liliana Werner and Dr. Nick Mamalis for their invaluable guidance and expertise in the DBS diagnosis in case 3.

Funding

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (Grant number JP25K20212 to K.K.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors attest that they meet the current International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship. Conception and design: K.K. and Y.M. Acquisition of data: K.K., Y.M., M.I., and K.I. Data analysis and interpretation of data: K.K., Y.M., H.K., A.I., E.N., and N.Y. Writing and revision of the manuscript: K.K., Y.M., H.K., A.I., E.N., and N.Y. Additionally, all authors have reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Komatsu, K., Masuda, Y., Kubota, H. et al. Association of eosinophil major basic protein with intraocular lens dislocation in atopic dermatitis. Sci Rep 15, 16861 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02083-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02083-y