Abstract

Understanding the molecular underpinnings of CAD is essential for developing effective therapeutic strategies. This study aims to identify and analyze differentially expressed hub biomarkers in the peripheral blood of CAD patients. Based on RNA-seq datasets from the Gene Expression Omnibus database, machine learning algorithms including LASSO, RF, and SVM-RFE were applied. Furthermore, the hub biomarkers were enriched to ascertain their roles in immune cell expression and signaling pathways through GO, KEGG, GSVE, and GSVA. An in vivo experiment was conducted to verify the hub biomarkers. Eleven hub biomarkers (ITM2B, GNA15, PLAU, GNG11, HIST1H2BH, SLC11A1, RPS7, DDIT4, CD83, GNLY, and S100A12) were identified and associated with CD8 + T cells and NK cells. They were mainly involved in immune responses, cardiac muscle contraction, oxidative phosphorylation, and apoptotic signaling pathways. Moreover, ITM2B had the most importance and significance to be the biomarker of CAD patients. In conclusion, these findings point to the possibility of ITM2B as a biomarker on the inflammatory pathogenesis of CAD and suggest new options for therapeutic intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The pathophysiology of coronary artery disease (CAD), which continues to pose a serious threat to world health, is largely dependent on immunological and inflammatory pathways. With atherosclerosis being the main cause of CAD, recent developments have given us a better knowledge of the interaction between inflammation, immune response, and atherosclerosis1.

The functions of both innate and adaptive immune responses in CAD have been heavily highlighted in recent research. The role of immune cells in CAD has been the subject of more recent research. Monocytes and macrophages are primarily responsible for the formation of atherosclerotic plaque; they collect lipids and develop into foam cells, which make the plaque unstable2. It has been suggested that T cells, in particular CD4 + T cells, exacerbate the inflammatory environment in atherosclerotic lesions3. Furthermore, immunological homeostasis depends on the balance between several T cell subtypes, including Th17 and regulatory T cells (Tregs), and disturbance of this balance has been linked to atherosclerosis4. Furthermore, there has been an increased focus on the importance of certain cytokines and chemokines in CAD. When the NLRP3 inflammasome is active, a significant pro-inflammatory cytokine called IL-1β is generated, making it a target for therapeutic intervention. It has been linked to inflammation caused by atherosclerosis5. Ziltivekimab, a novel IL-6 ligand inhibitor, has been shown to have anti-inflammatory and antithrombotic properties. Another study examines the role of IL-6 in systemic atherothrombosis, aneurysm formation, stable coronary disease, acute coronary syndromes, heart failure, and atherothrombotic complications6.

A major contributing element to CAD is inflammation, and research has concentrated on finding inflammatory biomarkers. As an illustration, Prescott et al. used proteomics to pinpoint biological pathways and create prediction models for coronary microvascular dysfunction, a disorder linked to CAD7. The ability of protein biomarkers to diagnose and comprehend CAD is demonstrated by this study. The identification of these immunological pathways in CAD has resulted in new approaches to treatment. Although statins are mostly used to decrease cholesterol, they also have anti-inflammatory properties and have been demonstrated to influence the immune system, which lowers the risk of cardiovascular events8. In individuals with CAD, targeted immunotherapies including monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-1β, have demonstrated potential in lowering recurrent cardiovascular events9.

Despite the progress in the research on immunity and inflammation in CAD, numerous challenges remain. Modulating immune responses in CAD therapeutically requires careful consideration of the balance between anti - inflammatory benefits and potential impacts on host defense and tissue regeneration. There is still a pressing need for in - depth research on how to precisely regulate immune responses in treatment and how to further enhance the accuracy and reliability of biomarker detection for more personalized treatment strategies10. Furthermore, although previous studies have employed machine learning algorithms to screen characteristic genes and evaluate diagnostic efficacy11,12, there is significant room for exploration in comprehensively uncovering novel biomarkers and treatment targets in CAD by integrating bioinformatics.

Using the filtered hub differentially expressed immune-related biomarkers in the database, a novel monitoring diagnostic model of CAD was built in this work. The expression of many hub biomarkers was then used to build a stemness subtype classifier using three machine learning methods. With the use of this classifier, clinicians may now identify patients who are more likely to respond sensitively to immunotherapy. Early prevention can be implemented if these putative biomarkers properly predict the likelihood of developing CAD.

Methods

GEO data processing

Gene expression datasets were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. The datasets (GSE9820, GSE10195, GSE18608, GSE20686, GSE42148, GSE98583, GSE66360, and GSE60993) were selected based on their relevance to CAD and the availability of comprehensive gene expression profiles. The GSE9820 dataset involved 18 patients with severe triple-vessel CAD and 13 control patients without signs of CAD on angiography on the platform of GPL6255. The GSE10195 dataset involved 27 cases with angiographically significant CAD (≥ 70% stenosis in > 1 major vessel or ≥ 50% stenosis in > 2 arteries) and 14 controls with luminal stenosis of 0% on the platform of GPL1708. The GSE18608 dataset involved 10 CAD patients and 4 controls on the platform of GPL570. The GSE20680 dataset involved 87 CAD patients (with ≥ 70% stenosis in > 1 major vessel or ≥ 50% stenosis in > 2 arteries) and 108 controls (with luminal stenosis less than 50%) on the platform of GPL4133. The GSE42148 dataset involved 13 patients with angiographically confirmed CAD and 11 population-based asymptomatic controls with normal electrocardiograms on the platform of GPL13607. The GSE98583 dataset involved 12 CAD patients (6 patients with single-vessels disease and 6 patients with triple-vessels disease) and 6 controls (atypical angina with normal coronary angiogram) on the platform of GPL571. The GSE66360 dataset involved 49 CAD patients and 50 controls on the platform of GPL571. The GSE61144 involved 14 ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients and 10 normal controls on the platform of GPL6106. All the CAD group patients received satisfied at least 1 main blood vessel stenosis ≥ 50% with the coronary angiography technique, and the healthy control group was in accordance with all the vessels stenosis < 50% or without electrocardiogram change and clinical symptoms.

The Bioconductor package within R software (https://www.bioconductor.org/) was used for data analysis. Datasets were filtered, background corrected, log2 transformed and normalized. In addition, the datasets were merged, and the merged data were batch corrected using the Combat method of the “sva” package. Then, all the data from the three datasets were re-normalized by the ComBat algorithm (Fig. 1) to remove the batch effect and evaluated by principal component analysis (PCA).

Identification of hub biomarkers in CAD patients. (A) PCA cluster plot of GSE9820, GSE10195, GSE18608, GSE20686, GSE42148, GSE98583 and GSE66360 before batch effect removal and correction. (B) PCA cluster plot showed that batch effect has been removed. (C) Volcano plot of hub biomarkers between CAD patients and healthy controls. (D) Heatmap for the top 30 hub biomarkers CAD patients and healthy controls. Green, down-regulation (n = 93); Red, up-regulation (n = 36); Grey, not significant.

Combined differential analysis

The normalized-merged dataset was subjected to differential expression analysis to identify genes with significant expression changes between CAD patients and healthy controls. The |log2 Fold change (FC)| > 0.5 and P < 0.05 were set as the criteria for identifying differentially expressed biomarkers using the “limma” package in R.

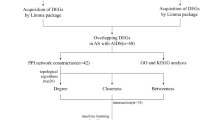

Machine learning approaches and screening of hub biomarkers

To further select potential CAD genes, three machine learning algorithms—least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression, random forest (RF), and support vector machine-recursive feature elimination (SVM-RFE) learning—were used. Regression analysis using LASSO has proven to be the suitable approach for analyzing high-dimensional data. By punishing the absolute magnitude of the regression coefficients, this technique aids in the reduction of overfitting. The regularization parameter (λ) was selected via 10-fold cross-validation using the “glmnet” package in R. The optimal λ corresponded to the minimum mean cross-validated error (lambda.min). The α parameter (mixing percentage between L1 and L2 penalties) was set to 1. RF is an ensemble prediction technique that assesses the significance of variables and can handle a high number of input variables. During training, this approach builds numerous decision trees, and the prediction it produces is the class mode. The number of trees (ntree) was set to 300, and the number of features randomly sampled at each split (mtry) was tuned using the out-of-bag (OOB) error. To deal with the non-linear relationship between variables, a kernel technique was used during the training process of the SVM-RFE model. A linear kernel was selected, and recursive feature elimination was performed using 10-fold cross-validation to determine the optimal subset of features. We used the “glmnet,” “RandomForest,” and “e1071” packages in R software to finish the three machine learning techniques. The genes identified by all three machine learning methods were intersected to derive a robust set of CAD characteristic genes.

Validation and grouping of hub biomarkers

The model’s diagnostic effectiveness was assessed using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC), area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) based on the selective hub biomarkers. Additionally, a different external dataset (GSE61144) and in vivo experiment were used to confirm the hub biomarkers’ expression levels and diagnostic significance. The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Longhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. 2019-N002, Supplementary file 1). The study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines13. The ApoE−/− mice were purchased from GemPharmatech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, Jiangsu, http://www.gempharmatech.com). These mice were bred at the Animal Center of Longhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine with free access to sterile water and food. Twenty ApoE−/− mice were randomly divided into 2 groups (10 mice/group): the control group (CON) and the model group (MOD). Mice in MOD received eight weeks of feeding of a high-fat diet (HFD). Meanwhile, 10 mice in CON were fed with a normal diet without any intervention. At the end of the experiments, mice were sacrificed via carbon dioxide asphyxiation, and then the mice aortas were obtained. Total RNA was extracted using the RNA Purification Kit (EZBioscience, CN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. ITM2B (Forward Primer 5’−3’: GAAGGTGACGTTCAACTCGG; Reverse Primer 3’−5’: CTCTGTCCAACCGGAACCAC) was designed using the online website PrimerBLAST of NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information, available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/) and synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

The distinctive biomarkers that were discovered were categorized according to how they expressed themselves. To investigate the variations in expression between these groups within the CAD and control populations, further differential analysis was carried out. Differential expression analysis was performed with the cut-off threshold of |log2 FC| > 0.5 and P < 0.05.

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were performed to elucidate the biological functions and pathways associated with the disease characteristic genes. This analysis helped in understanding the potential biological processes and pathways involved in CAD. GO analysis [comprising biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MF), and cellular components (CC)] and KEGG were carried out using the “clusterProfile,” “org.Hs.eg.db,” “enrichplot,” “ggplot2,” and “GOplot” packages in R, with P < 0.05 being a statistically significant difference.

Enrichment and variation analysis of gene set

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) and Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA) were conducted to determine whether the hub biomarkers showed immunologic differences significantly between the CAD and control groups. This analysis provided insights into the gene sets correlated with CAD phenotypes. We used the “limma,” “org.Hs.eg.db,” “clusterProfiler,” “enrichplot,” “reshape2,” “ggpubr,” “GSEABase,” and “GSVA” packages in R, with P < 0.05 considered significantly enriched. The “c2.cp.kegg.Hs.symbols.gmt” gene set was downloaded from the Molecular Signature Database (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp).

Immune cell infiltration analysis

Using the CIBERSORT method, the infiltration of different immune cells in CAD was investigated. Understanding the immune system and the function of various immune cells in CAD was made easier by this analysis. The machine learning technique known as the CIBERSORT deconvolution algorithm is based on linear support vector regression, a computation technique that determines the proportion of immune cells in tissues or cells. The experiment utilized the CIBERSORT deconvolution algorithm in conjunction with R to replicate the transcription characteristic matrix of 22 distinct types of immune cells (different situations of B cells, plasma cells, T cells, natural killer cells, monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, mast cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils). The parameters of CIBERSORT were set as 1000 permutations and P < 0.05. We contrasted the samples of immune cell infiltration from the CAD group with those from the control group. Meanwhile, the relationship between the hub biomarker and immune cells was explored.

Construction of Single-Gene CeRNA regulatory network

A competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) network was purely predicted for the hub gene identified in this study. This network helped in understanding the post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms involving miRNAs, and their target genes in the context of CAD. Three databases (miRanda, miRDB, TargetScan) were used to discover the related miRNAs and the SpongeScan was used to identify the targeted lncRNAs. Then the Cytoscape software (available at: https://cytoscape.org/; Version 3.10.1; data: February 1, 2024) was used to construct the network of ceRNA.

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were implemented using the R software version 4.3.2 (available at: https://www.r-project.org/; date: February 1, 2024). The correlation between the variables was determined using the Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation test. Differential expression analysis was performed with the cut-off threshold of |log2 FC| > 0.5. P value of two-tailed less than 0.05 was deemed to be statistically significant. A p-value was adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Results

Identification and screening of hub biomarkers

Following normalization and batch correction, principal component analysis confirmed the effective mitigation of batch effects in the merged dataset (GSE9820, GSE10195, GSE18608, GSE20686, GSE42148, GSE98583, and GSE66360) (Fig. 1A-B). After standardizing the dataset results, 129 differentially expressed genes (36 upregulated and 93 downregulated) were identified between 216 CAD patients and 206 healthy controls, with a |log2 FC| > 0.5 and P < 0.05. The top ten up-regulated biomarkers included CD14, FCN1, PLAUR, HCK, LILRA5, AQP9, HK3, TYROBP, CSF3R, BST1; while the top ten down-regulated biomarkers were ITM2B, RPS12, SDPR, GNG11, HIST1H3E, PF4 V1, CA2, CLEC1B, TUBB1, and PABPC3. The hub biomarkers were demonstrated on volcano plots (Fig. 1C) and heatmaps (Fig. 1D) of the merged dataset, suggesting they were likely to participate in the pathological process of CAD.

Machine learning analysis of hub biomarkers

A subset of 11 genes was consistently identified by the three approaches (LASSO regression, RF, and SVM-RFE). A comprehensive group of biomarkers distinctive to CAD is represented by these genes. After screening out 25 diagnostic biomarkers using LASSO regression (Supplementary file 2, Fig. 2A-B), we found 81 more biomarkers using the RF approach (Supplementary file 3, Fig. 2C-D), and 26 diagnostic genes using SVM-REF (Supplementary file 4, Fig. 2E-F). Eleven potential biomarkers were discovered after the hub biomarkers from the three machine learning techniques were overlapped: ITM2B, GNA15, PLAU, GNG11, HIST1H2BH, SLC11 A1, RPS7, DDIT4, CD83, GNLY, and S100 A12 (Fig. 2G). In addition, the violin figures (Fig. 3A-K) and line figure (Fig. 3L) showed the detailed differences of eleven biomarkers between CAD patients and healthy controls.

Three machine learning algorithms for identifying hub biomarkers. (A-B) LASSO regression algorithm. (C-D) RF algorithm; Mean Decrease Gini score > 2 was used as the threshold to determine whether a gene was selected. (E-F) SVM-REF algorithm. (G) Venn diagram identified eleven hub biomarkers that were shared by three feature selection algorithms.

Validation and grouping of the hub biomarker

We further evaluated the diagnostic values of these biomarkers. The AUC values of ROC curves were 0.703 of ITM2B (Fig. 4A), 0.687 of GNA15 (Fig. 4B), 0.658 of PLAU (Fig. 4C), 0.661 of SLC11 A1 (Fig. 4D), 0.677 of HIST1H2BH (Fig. 4E), 0.678 of RPS7 (Fig. 4F), 0.669 of GNG11 (Fig. 4G). The other four biomarkers with AUC ≤ 0.65, DDIT4 (AUC = 0.650), CD83 (AUC = 0.618), GNLY (AUC = 0.609), and S100 A12 (AUC = 0.609), respectively (Supplementary file 5). We found that only ITM2B had high accuracy with AUC > 0.7, sensitivity = 0.969, specificity = 0.420, PPV = 0.519, and NPV = 0.955, revealing the predictive efficacy of the biomarker signature. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV information of the other biomarkers showed in the Supplementary file 6. Subsequently, external validation was performed using the GSE61144 dataset (26 CAD patients, 7 normal controls) to evaluate whether the ITM2B biomarker was differentially expressed, revealing distinct expression profiles between CAD and control samples (Fig. 4H). The other differently expressed biomarkers were shown in Supplementary file 7. The expression level of ITM2B was lower in CAD patients than normal controls (P < 0.01). The ROC curve proved that the ITM2B biomarker based on logistic regression was reliable, with an AUC of 0.829 in the testing set (Fig. 4I). The ITM2B mRNA relative expression of the mouse aorta in the MOD group decreased significantly compared to the CON group (Fig. 4J).

ROC curves and validation of the eleven hub biomarkers. (A-G) ROC curves of the eleven hub biomarkers. (H) Expression of ITM2B in CAD patients compared to normal controls in the validation dataset (GSE 61144 dataset). (I) ROC curve of the predictive efficacy of ITM2B in the validation dataset. (J) The ITM2B mRNA relative expression. CON, control group. MOD, AS model group. **P < 0.01.

The hub biomarker ITM2B was grouped based on the expression patterns. Nine related biomarkers decreased significantly: CASP8, CLEC2B, ATP5E, CD300 A, SELL, RPS12, CSTA, S100 A9, and EIF1 AY (Fig. 5A). All the nine biomarkers had a positive relationship with the ITM2B, which meant all nine biomarkers also showed lower expression in CAD patients compared to healthy controls (Fig. 5B-C).

Functional enrichment analysis

GO and KEGG analyses provided insight into the biological functions and pathways associated with the CAD biomarkers. In terms of BP, GO enrichment analysis revealed that hub biomarkers were mainly enriched in regulation of enzymatic activities (regulation of peptidase activity, positive regulation of peptidase activity, positive regulation of endopeptidase activity), apoptotic processes (activation of cysteine-type endopeptidase activity involved in apoptotic process, positive regulation of cysteine-type endopeptidase activity involved in apoptotic process, regulation of cysteine-type endopeptidase activity involved in apoptotic process, positive regulation of cysteine-type endopeptidase activity), leukocyte activities (leukocyte migration, leukocyte cell-cell adhesion, granulocyte migration). For CC, hub biomarkers were significantly enriched in membrane-related components (secretory granule membrane, external side of plasma membrane, golgi-associated vesicle membrane, ficolin-1-rich granule membrane, tertiary granule membrane), ribosomal components (cytosolic small ribosomal subunit, small ribosomal subunit, small-subunit processome), structural and protective components (cornified envelope), complexes and assemblies (peptidase inhibitor complex). As for MF, hub biomarkers were enriched in enzymatic activity (cysteine-type endopeptidase activity involved in the apoptotic process); others were related to binding activities (specific binding to various molecules, playing critical roles in signaling, recognition, and enzymatic regulation) (Fig. 6A-E). The detailed scores of GO analysis were shown in Supplementary file 8.

Analysis of the KEGG signal pathways revealed that the hub biomarkers were mainly enriched in pathways associated with cell growth and death (apoptosis-multiple species, p53 signaling pathway), the immune system (IL-17 signaling pathway, RIG-I-like receptor signaling pathway, cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway), viral myocarditis, and infectious disease (Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection, legionellosis, platinum drug resistance) (Fig. 6F-J). The detailed scores of KEGG analysis were shown in Supplementary file 9.

Gene set enrichment and variation analysis

GSEA and GSVA highlighted gene sets that differed significantly between CAD and control groups, specifically noting immune response-related pathways. The gene set “c2.cp.kegg.Hs.symbols.gmt” exhibited notable enrichment, underscoring their relevance to CAD. The GSEA analysis showed that when ITM2B was highly expressed, these pathways were activated (Alzheimer’s disease, cardiac muscle contraction, oxidative phosphorylation, Parkinson’s disease, ribosome), while when ITM2B was lowly expressed, these pathways were activated (asthma, B cell receptor signaling pathway, intestinal immune network for IGA production, JAK/STAT signaling pathway, systemic lupus erythematosus) (Fig. 7A-B). We further used GSVA to validate the immune-related pathways of the gene set. The GSVA analysis discovered that pathways (endometrial cancer, acute myeloid leukemia, tight junction, adipocytokine pathway, JAK/STAT pathway, calcium pathway, inositol phosphate metabolism, B cell receptor pathway, FC epsilon RI pathway, amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism) were upregulated when ITM2B was expressed highly; however, pathways (cardiac muscle contraction, Parkinson’s disease, oxidative phosphorylation, Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, spliceosome, taurine and hypotaurine metabolism, protein export, RNA degradation, ribosome) were downregulated when ITM2B was expressed low (Fig. 7C). Notably, downregulation of ITM2B was found to be associated with immune responses, cardiac muscle contraction, and oxidative phosphorylation.

Gene set enrichment and immune function. (A) The top five pathways with ITM2B high expression by GSEA. (B) The top five pathways with ITM2B low expression by GSEA. (C) Bar plot of differentially expressed biomarkers enriched in the pathways based on ITM2B by GSEA. (D) Scores of immune-related functions between the ITM2B high and low expression groups. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Then we scored the immune-related function between the ITM2B high and low expression groups. The higher score meant more active function. When the ITM2B expression was low, activity in the following immunity-related functions (APC costimulation, CCR, checkpoint, cytolytic activity, HLA, MHC class I, pDCs, co-inhibition and co-stimulation of T cells, Th1 cells, TIL, and Treg) showed significant differences; on the contrary, when ITM2B was highly expressed, neutrophils and type II IFN response had a significant difference (Fig. 7D).

Immune cell infiltration analysis

CIBERSORT analysis revealed differential immune cell infiltration patterns in CAD patients compared to controls. The distribution of 22 immune cells in the merged databases is demonstrated in Fig. 8A. Notably, the results of the immune cell infiltration analysis demonstrated a significantly higher infiltration of CD8 + T cells, Tregs, T cells gamma delta, activated NK cells, monocytes, and macrophages M1 in CAD than in healthy controls, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of CAD progression (Fig. 8B). However, there was a significantly lower infiltration of CD4 + memory resting and activated T cells, resting NK cells, macrophages M2, activated dendritic cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils in CAD than in healthy controls.

Immune cell infiltration analysis. (A) The relative percentage of 22 immune cell subpopulations between CAD patients and healthy controls. (B) Boxplot illustrates different fractions of 22 immune cells in CAD and control samples. (C) Correlation between ITM2B and immune cells. (D-E) ITM2B negatively correlates with activated NK cells and CD8 + T cells. (F) Correlation heatmap of 22 immune cells. Red and blue represent positive and negative correlation, respectively.

A correlation was also observed between the ITM2B hub biomarker and the presence of specific immune cell types. Correlation analysis of 22 immune cells with ITM2B demonstrated positive correlations of macrophages M2 (cor = 0.261; P < 0.001), neutrophils (cor = 0.244; P < 0.001), T cells follicular helper (cor = 0.150; P = 0.01), CD4 + T cells memory activated (cor = 0.142; P = 0.015), and NK cells resting (cor = 0.115; P = 0.049); negative correlations with NK cells activated (cor = −0.368; P < 0.001), CD4 + T cells naive (cor = −0.221; P < 0.001), CD8 + T cells (cor = −0.199; P < 0.001), B cells memory (cor = −0.183; P = 0.002), mast cells resting (cor = −0.128; P = 0.029), and Tregs (cor = 0.726; P = 0.047) (Fig. 8C). These results further demonstrated the crucial role played by these immune cells in the CAD progression.

In summary, ITM2B negatively correlates with activated NK cells (Fig. 8D) and CD8 + T cells (Fig. 8E), which are among the immune cells significantly elevated in CAD patients, indicating their central role in its pathogenesis. Additionally, there were correlations between the changed peripheral immune cells (Fig. 8F), such as NK cells and CD8 + T cells (r = 0.62), which had a positive relationship.

CeRNA network construction

The single-gene ceRNA network was constructed, elucidating the complex post-transcriptional regulation involving miRNAs and their target genes in CAD. The network revealed 156 miRNAs that were related to the ITM2B gene, but only 52 miRNAs had a connection with different lncRNAs (Fig. 9).

Discussion

Heart disease is still one of the main reasons for mortality worldwide. In 2021, the location of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in adults is most often a home or residence (73.4%), followed by public settings (16.3%)1. It suggests that early identification of CAD is essential to reducing the ensuing mortality. Bioinformatics can now more efficiently and rapidly search for important genes associated with disease incidence and progression pathways thanks to high-throughput microarray technologies. This has created new opportunities for the diagnosis, treatment, and development of novel drugs14. He et al. conducted a comprehensive bioinformatics analysis to identify novel immune-related biomarkers of CAD, underscoring the role of immune cell infiltration in the disease15. Similarly, Zhang et al. utilized single-cell sequencing, bioinformatics, and machine learning to identify hub biomarkers, demonstrating the efficacy of these technologies in understanding cardiovascular diseases16.

Based on large-scale gene expression datasets and sophisticated machine learning algorithms, the current work has discovered a strong collection of biomarkers for CAD. 11 hub biomarkers—ITM2B, GNA15, PLAU, GNG11, HIST1H2BH, SLC11 A1, RPS7, DDIT4, CD83, GNLY, and S100 A12—were consistently highlighted in LASSO regression, RF, and SVM-RFE algorithms, according to our data, indicating a major significance for these biomarkers in the pathophysiology of CAD. The biomarker that exhibited the best diagnostic accuracy in our investigation, ITM2B, has been linked to atherosclerotic alterations in human coronary artery segments in the past, indicating its possible role as a therapeutic target17. Moreover, the association of ITM2B with apoptotic pathways18, as revealed by our GO and KEGG analyses, could provide insights into the molecular mechanisms of plaque instability, a critical event in acute coronary syndromes. Related ITM2B indicators, like CASP8, suggest that endothelial and smooth muscle cell death contributes to plaque instability, a major risk factor for heart attacks and strokes; CLEC2B, might influence inflammatory processes19 associated with atherosclerosis and be a novel antiplatelet target20; CD300 A, also has a connection with inflammation and efferocytosis of apoptotic cells21. The multifactorial character of CAD, where several biological processes converge to influence disease development, is reflected in the intricate interactions between these indicators. Furthermore, in contrast to previously published results, only the AUC value of ITM2B exceeded 0.7 in the comprehensive datasets of this investigation. We hypothesize that this is the case since this study’s dataset is the most extensive. As a result, we obtain a different outcome than previously. This demonstrates even more how crucial ITM2B is as a biomarker in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis.

The cellular complexity of atherosclerotic plaque formation and rupture is underscored by the biological processes and pathways enriched among the identified biomarkers, especially those linked to immune responses, cardiac muscle contraction, oxidative phosphorylation, and apoptotic signaling. Studies that have highlighted the part that immune cells, inflammatory processes, and apoptosis play in the pathophysiology of CAD are consistent with these findings22,23. Given that pro-inflammatory cells like CD8 + T cells and NK cells are significantly more prevalent in CAD patients, our data further emphasizes the significance of immune cell infiltration in the disease. These results are consistent with recent studies that have emphasized the function of NK cells and T cell subsets in the chronic inflammatory response that characterizes CAD. Acute coronary events may be exacerbated by CD8 + T lymphocytes due to their potent cytotoxic and pro-inflammatory properties24. Correlations are also found between CD8 + T cells and the degree of carotid stenosis25. In CAD, NK cell numbers are reduced and abnormal activity is seen. But the evidence for NK cells’ involvement in atherogenesis is hazy at best and needs more explanation26.

Furthermore, an additional layer of regulatory intricacy is added by the ceRNA network, including ITM2B and related miRNAs as well as lncRNAs. It has been demonstrated that CAD and other cardiovascular illnesses are significantly impacted by the complex interactions that miRNAs have with the genes that they target. Targeting post-transcriptional regulatory processes with therapeutic treatments may be made possible by this network.

Several bioinformation articles of CAD have been published before. Feng et al.27 construct a diagnostic model of advanced-stage CAD based on the screen of 14 differentially expressed genes. However, they only use LASSO regression to identify the potential genes and include three databases that are all in our analysis. Huang et al.28 also discovered that MMP9, PELI1, THBD, and ZFP36 may be predicted biomarkers for CAD. Similarly, they only analyze four datasets and do not perform any internal or external validation. Based on these, there is a potential concern about the integrity of the results. Then we design this study and include all the datasets in the GEO database. Moreover, our study’s reliance on machine learning raises questions about the interpretability of complex models and the need for explainable artificial intelligence in healthcare applications. The interpretability of such models is crucial for clinicians to trust and understand the predictions made by artificial intelligence systems. We also conduct an external validation to testify to the results.

Despite these advancements, there are still challenges in implementing these findings in clinical settings. The molecular heterogeneity of CAD necessitates customized approaches to diagnosis and treatment. Moreover, the integration of biomarkers into existing clinical practices requires confirmation across a range of demographics and clinical scenarios. The prognostic use of biomarkers with high sensitivity but low specificity, such as ITM2B, is problematic. Although sensitive biomarkers are excellent for initial screening, their poorer specificity means that false positives may occur when creating diagnostic algorithms. Some limitations also should be noticed. One limitation of our study is the lack of in-depth functional validation of the identified biomarkers. Most of our analysis was based on bioinformatics prediction, and further experimental studies, such as in vitro and in vivo experiments, are required to confirm the roles of these biomarkers in the pathogenesis of CAD. In addition, the datasets we used, although comprehensive, may still have limitations in representing the full spectrum of CAD patients. Different ethnic groups, genders, and age-related factors may influence the gene expression patterns and biomarker significance, which were not fully explored in our current study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our research adds to the expanding list of suggestive CAD biomarkers bolstered by machine learning analysis. Through NK cells and CD8 + T cells, the discovered ITM2B biomarker provides fresh perspectives on the inflammatory pathogenesis of CAD and suggests new options for therapeutic intervention. Subsequent investigations ought to concentrate on the clinical verification of these indicators and the creation of customized therapeutic approaches that consider the molecular intricacy of CAD.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Pubmed GEO datasets repository, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gds/?term=]

Abbreviations

- CAD:

-

coronary artery disease

- Tregs:

-

regulatory T cells

- NCBI:

-

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- GEO:

-

Gene Expression Omnibus

- PCA:

-

principal component analysis

- FC:

-

Fold change

- LASSO:

-

least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- RF:

-

random forest

- SVM-RFE:

-

support vector machine-recursive feature elimination

- ROC:

-

receiver operating characteristic

- AUC:

-

area under the curve

- PPV:

-

positive predictive value

- NPV:

-

negative predictive value

- CON:

-

control group

- MOD:

-

model group

- HFD:

-

high fat diet

- GO:

-

Gene Ontology

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- BP:

-

biological processes

- MF:

-

molecular functions

- CC:

-

cellular components

- GSEA:

-

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

- GSVA:

-

Gene Set Variation Analysis

- ceRNA:

-

competing endogenous RNA

References

Tsao, C. W. et al. Heart disease and stroke Statistics-2023 update: A report from the American heart association. Circulation 147, e93–e621. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001123 (2023).

Gao, C. et al. Treatment of atherosclerosis by macrophage-biomimetic nanoparticles via targeted pharmacotherapy and sequestration of Proinflammatory cytokines. Nat. Commun. 11, 2622. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16439-7 (2020).

Saigusa, R., Winkels, H. & Ley, K. T cell subsets and functions in atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 17, 387–401. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-020-0352-5 (2020).

Hu, W., Li, J. & Cheng, X. Regulatory T cells and cardiovascular diseases. Chin. Med. J. 136, 2812–2823. https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000002875 (2023).

Everett, B. M. et al. Anti-Inflammatory therapy with Canakinumab for the prevention of hospitalization for heart failure. Circulation 139, 1289–1299. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038010 (2019).

Ridker, P. M. & Rane, M. Interleukin-6 signaling and Anti-Interleukin-6 therapeutics in cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 128, 1728–1746. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.319077 (2021).

Prescott, E. et al. Proteomics to identify biological pathways and develop prediction models of coronary microvascular dysfunction in women with angina and no obstructive coronary artery disease. Eur. Heart J. 43 https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac544.1132 (2022).

Ridker, P. M. Residual inflammatory risk: addressing the obverse side of the atherosclerosis prevention coin. Eur. Heart J. 37, 1720–1722. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw024 (2016).

Libby, P. & Hansson, G. K. Inflammation and immunity in diseases of the arterial tree: players and layers. Circ. Res. 116, 307–311. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.301313 (2015).

Hansson, G. K., Libby, P. & Tabas, I. Inflammation and plaque vulnerability. J. Intern. Med. 278, 483–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12406 (2015).

Zhang, D., Guan, L. & Li, X. Bioinformatics analysis identifies potential diagnostic signatures for coronary artery disease. J. Int. Med. Res. 48, 300060520979856. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060520979856 (2020).

Liu, H. et al. Alterations in the gut Microbiome and metabolism with coronary artery disease severity. Microbiome 7, 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-019-0683-9 (2019).

Percie du Sert. Reporting animal research: explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000411. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000411 (2020).

Tcheandjieu, C. et al. Large-scale genome-wide association study of coronary artery disease in genetically diverse populations. Nat. Med. 28, 1679–1692. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01891-3 (2022).

He, T. et al. Immune cell infiltration analysis based on bioinformatics reveals novel biomarkers of coronary artery disease. J. Inflamm. Res. 16, 3169–3184. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S416329 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Identification of hub biomarkers of myocardial infarction by single-cell sequencing, bioinformatics, and machine learning. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 939972. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.939972 (2022).

Chen, J. X. et al. Quantitative proteomics reveals the regulatory networks of circular RNA BTBD7_hsa_circ_0000563 in human coronary artery. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 34, e23495. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.23495 (2020).

Ferreira, R. M. et al. The infertility of Repeat-Breeder cows during summer is associated with decreased mitochondrial DNA and increased expression of mitochondrial and apoptotic genes in oocytes. Biol. Reprod. 94, 66. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod.115.133017 (2016).

Niu, M. et al. Discovery of CLEC2B as a diagnostic biomarker and screening of Celastrol as a candidate drug for psoriatic arthritis through bioinformatics analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18, 390. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-023-03843-0 (2023).

Harbi, M. H., Smith, C. W., Nicolson, P. L. R., Watson, S. P. & Thomas, M. R. Novel antiplatelet strategies targeting GPVI, CLEC-2 and tyrosine kinases. Platelets 32, 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537104.2020.1849600 (2021).

Nakahashi-Oda, C. et al. CD300a Blockade enhances efferocytosis by infiltrating myeloid cells and ameliorates neuronal deficit after ischemic stroke. Sci. Immunol. 6, eabe7915. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.abe7915 (2021).

Mosquera, J. V. et al. Integrative single-cell meta-analysis reveals disease-relevant vascular cell States and markers in human atherosclerosis. Cell. Rep. 42, 113380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.113380 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. p55gamma degrades RIP3 via MG53 to suppress ischaemia-induced myocardial necroptosis and mediates cardioprotection of preconditioning. Cardiovasc. Res. 119, 2421–2440. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvad123 (2023).

Yu, T. Characterization of CD8(+)CD57(+) T cells in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 12, 466–473. https://doi.org/10.1038/cmi.2014.74 (2015).

Kolbus, D. et al. Association between CD8 + T-cell subsets and cardiovascular disease. J. Intern. Med. 274, 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12038 (2013).

Dounousi, E., Duni, A., Naka, K. K., Vartholomatos, G. & Zoccali, C. The innate immune system and cardiovascular disease in ESKD: monocytes and natural killer cells. Curr. Vasc Pharmacol. 19, 63–76. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570161118666200628024027 (2021).

Feng, X. et al. Identification of diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets in peripheral immune landscape from coronary artery disease. J. Transl Med. 20, 399. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-022-03614-1 (2022).

Huang, K. K., Zheng, H. L., Li, S. & Zeng, Z. Y. Identification of hub genes and their correlation with immune infiltration in coronary artery disease through bioinformatics and machine learning methods. J. Thorac. Dis. 14, 2621–2634. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-22-632 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We apologize to our colleagues in the field whose work could not be included due to space limitations. We thank all members of the research team of Professor Yun Guan from Johns Hopkins University for their comments and suggestions during the development of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation to YRW [grant number 82204849] and to PL [grant number 82074200]; Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Project of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission to YRW [grant number 2022QN056]; “Clinical research-oriented talents training program” in the Affiliated Hospital of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine to YRW [grant number 2023LCRC01]; Clinical Technology Innovation Cultivation Program of Longhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine to YRW [grant number PY2022008]; Regional medical Centre of Longhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine to YRW [grant number ZYZK001-029].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YRW and PL conceived and designed the experiments. XDC, LLT, LYT and YZ performed the analysis and software. WNK and WZ validated the results by vitro experiments. XDC and LLT wrote the original manuscript. LYT revised the manuscript. YW reviewed and edited the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, X., Tao, L., Tian, L. et al. Identification of hub biomarkers in coronary artery disease patients using machine learning and bioinformatic analyses. Sci Rep 15, 17244 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02123-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02123-7