Abstract

As modern power grids grow increasingly complex with the widespread deployment of renewable energy and distributed energy storage systems (ESS), ensuring robust and resilient black-start capabilities has become a critical challenge. Traditional black-start approaches, which typically rely on centralized hydro or diesel generators, are increasingly inadequate due to rising network complexity, the stochastic nature of renewables, and growing exposure to cyber-physical threats. To overcome these limitations, this study introduces a quantum-enhanced framework for dynamic network reconfiguration and topological optimization of ESS to support black-start restoration. The proposed method leverages quantum graph theory and quantum annealing to dynamically determine optimal ESS connectivity and energy redistribution pathways, enabling rapid grid recovery under diverse failure scenarios, including those involving cyber-physical disruptions. By integrating quantum annealing algorithms, the framework efficiently addresses the combinatorial complexity of large-scale ESS placement and dispatch, outperforming traditional heuristic and classical optimization techniques in both computational speed and solution quality. The approach is formulated through a comprehensive mathematical model that captures key interactions between network topology, energy flow dynamics, and black-start performance indicators such as restoration time, efficiency, and resilience. Simulation results on a 300-bus synthetic power grid with high levels of renewable penetration demonstrate that the proposed quantum-assisted strategy reduces restoration decision time by up to 50%, optimizes energy allocation, and significantly improves system robustness. These findings highlight the transformative potential of quantum computing in enabling intelligent, adaptive black-start planning, offering a powerful tool for enhancing the resilience of future energy systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The growing dependence on networked energy storage systems (ESS) in modern power grids has highlighted the urgent need for more resilient and efficient black-start capabilities. Black-start refers to the process of restoring power to the grid following a total or partial outage without relying on external electricity sources1. Traditionally, this process has depended on large-scale hydroelectric facilities and diesel generators to supply the initial restart energy2. However, the transition toward renewable energy, distributed ESS, and smart grid architectures presents new challenges for conventional black-start strategies. These include the intermittent nature of renewable generation, increasingly complex grid topologies, and heightened exposure to cyber-physical risks. As a result, there is a pressing need for advanced optimization techniques to enable the dynamic coordination and reconfiguration of ESS networks, ensuring faster and more robust grid restoration under uncertain and adverse conditions3,4.

Existing studies on black-start optimization primarily focus on classical optimization techniques such as mixed-integer linear programming, heuristic approaches, and robust control strategies to allocate resources and optimize restoration sequences5. However, as grid infrastructures become increasingly complex, these traditional approaches struggle with scalability, combinatorial complexity, and real-time adaptability. The rise of quantum computing has introduced new possibilities for addressing such computationally intractable problems by leveraging quantum parallelism and probabilistic computation6,7,8. In particular, quantum graph theory and quantum annealing have emerged as powerful tools to tackle high-dimensional optimization problems that involve dynamic network reconfiguration, resilience enhancement, and energy flow management. Despite the promising potential of quantum-inspired methods, their application to black-start optimization in network-type ESS remains largely unexplored9.

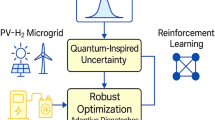

To address these challenges, this paper proposes a novel quantum topological optimization framework for enhancing black-start capabilities in network-type ESS. The core innovation of this study lies in leveraging quantum graph theory to dynamically reconfigure ESS connectivity, optimize energy redistribution pathways, and minimize restoration time under various failure scenarios. Unlike conventional black-start strategies that rely on pre-determined restoration sequences and rule-based heuristics, our approach utilizes a quantum-inspired probabilistic model to identify optimal energy dispatch patterns in a dynamically evolving grid environment. By integrating quantum annealing into the optimization process, this framework effectively handles the combinatorial complexity of ESS placement and energy routing, offering a more scalable and efficient alternative to classical methods. The proposed model not only ensures a faster restoration process but also enhances resilience by incorporating cyber-physical attack mitigation strategies within the black-start planning paradigm.

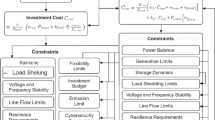

From a methodological perspective, this study develops a rigorous mathematical framework to capture the interplay between network topology, energy redistribution, and resilience in black-start scenarios. The optimization model consists of a multi-objective function that minimizes black-start recovery time, maximizes energy redistribution efficiency, and ensures network resilience against failures and cyber threats. The constraints imposed on the system include energy balance, network connectivity, ESS capacity limitations, power dispatch requirements, voltage and frequency stability, contingency planning, and quantum-enhanced decision constraints. The incorporation of quantum graph-based analysis allows the identification of optimal ESS configurations that maintain stability even under extreme disruption conditions. Moreover, quantum annealing is used to solve the large-scale combinatorial problem associated with reconfiguring network-type ESS, significantly reducing computational complexity and solution time. The uniqueness of this paper lies in its integration of quantum computing principles into the black-start optimization domain, a field that has traditionally been dominated by classical computational approaches. While previous works have explored robust and stochastic optimization for power system restoration, this study is the first to employ quantum-inspired topological optimization for dynamically restructuring energy storage networks. Additionally, the proposed framework is designed to be resilient against cyber-physical attacks, ensuring that black-start procedures remain secure and efficient even in the presence of adversarial disruptions. The hybridization of quantum graph theory with energy system resilience modeling represents a paradigm shift in how black-start strategies are formulated and executed, paving the way for a new generation of intelligent, self-adaptive grid recovery mechanisms.

This research makes four key contributions. First, it introduces a quantum topological optimization framework that leverages quantum graph theory for dynamically reconfiguring network-type ESS to support rapid and resilient black-start operations. Second, it incorporates quantum annealing as a powerful optimization tool to efficiently solve the large-scale combinatorial problem of ESS placement and energy dispatch, outperforming conventional heuristics in both speed and solution quality. Third, it enhances resilience by integrating cyber-physical attack mitigation strategies into the black-start optimization model, ensuring robust system recovery under both natural failures and targeted disruptions. Finally, it provides a comprehensive mathematical formulation that captures the complex interactions between network topology, energy redistribution, and black-start dynamics, offering a novel approach to resilient power system restoration. By addressing the limitations of traditional black-start methodologies and harnessing the computational advantages of quantum mechanics, this study establishes a transformative framework for future energy system resilience planning.

Literature review

With the increasing penetration of renewable energy and the decentralization of power generation, black-start planning has evolved to incorporate distributed resources such as microgrids, battery storage, and grid-forming inverters. Researchers have explored stochastic and robust optimization techniques to account for the uncertainty associated with renewable generation, load variations, and system contingencies. Probabilistic models have been developed to enhance the reliability of black-start operations under fluctuating supply conditions. These methods typically use scenario-based optimization, chance-constrained programming, and robust decision-making frameworks to improve the flexibility of black-start strategies. Despite these advancements, the scalability of classical optimization methods remains a challenge, especially when dealing with high-dimensional, dynamically evolving grid configurations10,11,12.

Recent efforts have introduced machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) techniques to optimize black-start processes. Reinforcement learning (RL) models, for instance, have been applied to develop adaptive restoration strategies that learn optimal decision-making policies through repeated interactions with simulated power systems13. Supervised learning approaches have been utilized to train predictive models based on historical restoration data, enabling faster and more efficient planning of black-start sequences. While ML-based methods offer promising improvements in automation and adaptability, they often require extensive training datasets and struggle with generalization to unseen grid disruptions14,15. Additionally, these models lack the theoretical guarantees of optimality and robustness that are inherent in classical optimization frameworks6,16.

Another significant research direction in black-start optimization involves the use of game-theoretic and resilience-based strategies to address cyber-physical threats. Given the increasing risk of cyberattacks on power grids, several studies have investigated defensive black-start planning that incorporates adversarial modeling and attack mitigation strategies. These works explore the impact of false data injection attacks (FDIAs), denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, and coordinated physical sabotage on black-start procedures. Optimization models incorporating security constraints have been proposed to ensure that black-start sequences remain feasible even under compromised grid conditions17,18. While these approaches enhance grid resilience, they often rely on static assumptions about attack vectors and require extensive computational resources to simulate multiple attack-defense scenarios.

A particularly relevant field of research for this study is network reconfiguration and topological optimization in energy systems. Many studies have examined how modifying network topology can improve resilience and recovery performance in blackout scenarios. Graph theory-based approaches have been used to model power grid structures and analyze connectivity patterns that influence restoration effectiveness19. These methods leverage concepts such as minimum spanning trees, network flow optimization, and centrality-based prioritization to determine the most efficient reconfiguration strategies. However, classical graph-based optimization techniques face limitations in solving large-scale problems with combinatorial complexity, as traditional solvers struggle to efficiently explore the vast solution space of possible network configurations.

Quantum computing has emerged as a promising alternative for solving complex optimization problems in power systems, including black-start optimization. Quantum annealing, in particular, has demonstrated advantages in handling combinatorial optimization problems by leveraging quantum parallelism to explore multiple solutions simultaneously20. Recent research has applied quantum-inspired techniques to power flow optimization, grid dispatch scheduling, and contingency analysis. In addition to earlier studies focusing on quantum approaches for economic dispatch and unit commitment, recent research efforts have expanded the application of quantum computing in broader power system domains. QML methods have been explored for grid resilience enhancement, enabling rapid fault detection and adaptive control under dynamic operating conditions21. Emerging works have also applied quantum annealing and variational quantum algorithms to optimize network reconfiguration, load restoration, and system recovery planning22. These developments demonstrate the growing potential of quantum techniques not only in classical optimization tasks but also in real-time decision-making and resilience-oriented applications within complex cyber-physical energy infrastructures. However, the integration of quantum computing into black-start planning remains largely unexplored23. Most existing studies in quantum optimization for power grids focus on economic dispatch, unit commitment24, and state estimation rather than dynamic restoration processes. The potential for quantum-enhanced network reconfiguration, particularly using quantum graph theory, is an area that has not yet been fully developed in the literature25. Furthermore, the use of quantum-inspired topological analysis for grid resilience has received limited attention26. While classical topological optimization has been applied to identify critical network structures, quantum-assisted graph algorithms provide a fundamentally different approach by encoding network connectivity into quantum states and solving for optimal configurations with superior computational efficiency27. Quantum graph-based optimization has been studied in other domains, such as telecommunications and logistics, but its application to energy storage placement, power routing, and black-start reconfiguration remains largely theoretical28. Given the increasing complexity of modern power grids, the potential of quantum computing to transform black-start planning through advanced topological optimization is an area with significant research potential.

Mathematical modelling and methodology

This section presents the mathematical formulation and methodological framework of the proposed quantum-enhanced topological optimization approach for black-start operations in network-type energy storage systems (ESS). The mathematical model is developed to rigorously capture the critical interactions between network topology, energy redistribution dynamics, and resilience considerations. Subsequently, the methodology incorporates quantum graph theory and quantum annealing techniques to effectively handle the complex combinatorial optimization challenges involved in dynamically reconfiguring ESS connectivity and dispatch strategies. The details of the objective function formulation, system constraints, and the integration of quantum computational methods are elaborated in the following subsections.

Black-start restoration is a delicate process where every second matters. This equation serves as the fundamental objective, minimizing the time required for complete grid recovery while factoring in quantum graph-based reconfigurations. The first term represents the normalized restoration time \(\Theta _{i,t}^{\text {rest}}\) at each node \(i\), weighed by the global restoration limit \(\Gamma ^{\text {max}}\). The second term ensures efficient power redistribution by minimizing the quantum-assisted curtailment \(\Lambda _{i,j,t}^{\text {cur}}\), normalized by its upper bound \(\Lambda ^{\text {max}}\). Lastly, the third term accounts for system dynamics by considering the stability function \(\Xi _{i,t}^{\text {dyn}}\), constrained by the system-wide dynamic threshold \(\Upsilon ^{\text {max}}\). The weight coefficients \(\alpha , \beta ,\) and \(\gamma\) tune the relative importance of these three objectives, ensuring balanced restoration.

Energy must be distributed wisely across the network for a successful black-start. This equation ensures that the redistribution of stored energy follows the most efficient and least wasteful pathways. The term \(\Omega _{i,j,t}^{\text {flow}}\) quantifies the actual power flow across edge \((i,j)\), normalized against the maximum permitted flow \(\Omega ^{\text {max}}\). The second term evaluates energy conversion efficiency \(\zeta _{i,k,j,t}^{\text {eff}}\), particularly for power injected by distributed ESS. The final term considers reactive power support \(\Phi _{\ell ,t}^{\text {react}}\), which is essential for stabilizing voltage profiles during transient recovery. The coefficients \(\delta , \epsilon , \eta\) prioritize energy flow, conversion efficiency, and reactive power support, respectively.

A resilient energy storage network is crucial for mitigating failures and attacks. This function maximizes resilience by considering system-wide robustness and contingency management. The first term ensures that available stored energy reserves \(\Sigma _{i,t}^{\text {res}}\) are maximized relative to their upper limit \(\Sigma ^{\text {max}}\), preserving emergency energy sources. The second term strengthens the network by reinforcing security attributes \(\Theta _{i,j,t}^{\text {secure}}\), ensuring nodes are well-connected against potential failures. Finally, the third term counteracts targeted cyber and physical attacks \(\Psi _{p,t}^{\text {attack}}\), reinforcing security via strategic deception and redundancy. The weighting parameters \(\kappa , \lambda , \mu\) prioritize different resilience aspects, balancing stability and security.

Quantum annealing offers an elegant and powerful solution to the network reconfiguration problem, enabling rapid convergence towards optimal ESS placements. The first term \(\Gamma _{i,j,t}^{\text {anneal}}\) quantifies the annealing process’s effectiveness in selecting optimal paths, ensuring that the search for an optimal configuration remains computationally efficient. The second term incorporates quantum-optimal routing \(\Xi _{m,t}^{\text {qopt}}\), minimizing phase mismatches in the power grid. Finally, \(\Pi _{q,t}^{\text {phase}}\) accounts for quantum-induced phase corrections, ensuring that the quantum-assisted optimization process remains coherent and free of significant errors. The coefficients \(\rho , \sigma , \tau\) control the influence of these components, ensuring a balance between solution precision and computational feasibility.

To clarify the hybrid computing interaction, we adopt a quantum-classical iterative workflow in which discrete optimization variables-such as ESS-to-node connectivity (\(\Gamma _{i,j,t}^{\text {anneal}}\)), network path selections (\(\Xi _{m,t}^{\text {qopt}}\)), and black-start sequence flags (\(\Pi _{q,t}^{\text {phase}}\))-are solved using quantum annealing techniques. These binary decision variables are well-suited to combinatorial optimization and benefit from the quantum processor’s ability to explore high-dimensional solution spaces efficiently. In our implementation, these decision variables are formulated into a Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) model and mapped onto the physical qubits of the D-Wave Advantage 5000Q system. The quantum annealing process operates over cycles typically ranging from 20 to 100 milliseconds, depending on problem complexity and embedding overhead. Sparse connectivity between qubits imposes constraints on the structure of the embedded graph, which we address through minor embedding techniques to preserve logical variable relationships. Once a candidate configuration is obtained from the quantum layer, the classical high-performance computing (HPC) component evaluates its physical feasibility through AC optimal power flow (AC-OPF) simulations. This includes validation of power flow values, nodal voltages (\(V_{i,t}\)), frequency dynamics (\(f_{i,t}\)), and related system constraints. The quantum output is decoded into dispatch instructions and fed into the classical solver. If violations are detected, the classical feedback is used to iteratively refine the quantum search space by adjusting constraint weights or modifying annealing parameters. This hybrid loop continues until both optimization objectives and operational feasibility are satisfied, enabling a reliable and efficient decision-making process for black-start restoration.

This equation guarantees that at every node \(i\), power balance is maintained. The left-hand side captures the net power exchanged with neighboring nodes, power generated locally, and the local load demand. The right-hand side accounts for stored energy contributions, discharging energy from ESS, and renewable generation sources such as wind and solar. The weighting factors \(\eta _m\), \(\gamma _m\), \(\zeta _k\), and \(\xi _k\) represent conversion efficiencies and dispatch coefficients, ensuring an accurate representation of power conservation within the black-start recovery process.

A network must remain connected to facilitate a resilient black-start process. This constraint ensures that the reconfigured energy network forms a spanning tree structure by maintaining sufficient active transmission paths. The binary variable \(\Theta _{i,j,t}^{\text {cut}}\) represents whether an edge is temporarily disconnected due to faults or intentional reconfiguration. The summation over adjacency weights \(A_{i,j,t}\) guarantees that the graph remains connected with at least \(|\mathscr {N}| - 1\) edges.

Energy storage systems have physical constraints on their charge levels. This equation enforces an upper bound \(S_{i,t}^{\text {max}}\) and a lower bound \(S_{i,t}^{\text {min}}\) on the stored energy at node \(i\), ensuring that no energy storage device operates beyond its designed capacity.

Successful black-start operation requires that a minimum power \(P^{\text {req}}\) be provided by the initially activated energy sources. This constraint ensures that the combined startup power from designated black-start nodes \(\mathscr {N}^{\text {start}}\) is sufficient to meet the minimum requirements at the beginning of the restoration process.

Load restoration must be carefully sequenced to prevent excessive demand surges. The binary variable \(\Theta _{i,t}^{\text {seq}}\) ensures that loads are restored according to a predefined priority, while \(P_{t}^{\text {max}}\) represents the maximum allowable power restoration at each time step. This constraint prevents uncontrolled surges that could destabilize the recovering network.

Voltage regulation is crucial for grid stability. This constraint ensures that the voltage magnitude \(V_{i,t}\) at each node remains within safe operational limits, preventing undervoltage and overvoltage conditions that could damage equipment or lead to cascading failures.

Frequency deviations must be strictly controlled to maintain synchronous operation during black-start procedures. This constraint limits the rate of frequency change between consecutive time steps, ensuring that frequency fluctuations remain within tolerable limits \(\Delta f^{\text {max}}\) to prevent loss of synchronism across the recovering grid.

Ensuring minimal energy loss in redistribution pathways is essential for effective black-start recovery. This constraint limits the aggregate power flow through network paths to the threshold \(\Psi _{t}^{\text {max}}\), ensuring energy is routed optimally across available connections. The terms \(\Omega _{i,j,t}^{\text {path}}\) and \(\Phi _{k,t}^{\text {path}}\) capture the quantum-assisted path optimization for power flow and reactive power routing, respectively.

Network connectivity is critical in ensuring black-start success. This equation guarantees that each node maintains a minimum connectivity level \(\Lambda _{i,t}^{\text {req}}\) to remain operational during the restoration phase. The term \(\Gamma _{i,j,t}^{\text {conn}}\) represents the active connections, while \(\Theta _{i,j,t}^{\text {fail}}\) captures whether a failure has disrupted the link between nodes \(i\) and \(j\).

Dynamic network adaptation is key to restoring power efficiently. This equation prevents excessive reconfiguration dynamics \(\Xi _{i,t}^{\text {dyn}}\) at each node, ensuring controlled transitions in topology during black-start. The binary variable \(\Theta _{i,t}^{\text {restore}}\) enforces constraints on when specific nodes are allowed to rejoin the grid.

Quantum annealing must be carefully constrained to ensure computational feasibility. This condition places an upper bound \(\Upsilon ^{\text {max}}\) on the probability-weighted quantum-assisted node connections \(\Lambda _{i,j,t}^{\text {qprob}}\), ensuring the optimization process does not exceed acceptable computational complexity limits.

Load shedding must be selectively applied to ensure that critical loads are prioritized. This constraint limits the power supplied to non-critical nodes, defined by \(\Theta _{i,t}^{\text {noncr}}\), ensuring that the total active load demand remains within the recoverable threshold \(P_{t}^{\text {lim}}\).

Reconfiguration must be strategically constrained to prevent unnecessary instability in the grid. This equation ensures that the sum of all reconfiguration actions \(\Xi _{i,j,t}^{\text {reconf}}\) and emergency interventions \(\Psi _{k,t}^{\text {emerg}}\) remains within the allowable threshold \(\Psi ^{\text {reconf}}\), preserving network stability.

Cybersecurity resilience must be maintained against potential attacks. This constraint enforces a minimum security level \(\Theta ^{\text {min}}\) across network links, ensuring that active cyber-defense measures are deployed based on the security status variable \(\Lambda _{i,j,t}^{\text {sec}}\), which determines whether a given edge is adequately protected.

Contingency measures must ensure that a minimum level of operational integrity is retained during black-start. This equation imposes a lower bound \(\Gamma ^{\text {min}}\) on the network’s functional components, ensuring that enough controllable units remain online to support the recovery process, even when failures \(\Theta _{i,t}^{\text {fail}}\) occur.

Efficient energy routing is essential to avoid overloading any given path during black-start operations. This constraint ensures that the total routed power \(\Xi _{i,j,t}^{\text {route}}\), storage dispatch power \(\Psi _{k,t}^{\text {storage}}\), and emergency dispatch capacity \(\Gamma _{\ell ,t}^{\text {dispatch}}\) remain within the operational capacity threshold \(\Theta _{t}^{\text {cap}}\). These terms ensure that energy distribution decisions are made with a balance between efficiency and resilience, minimizing unnecessary losses while ensuring adequate reserve allocation.

Power system stability is dependent on reactive power support and phase synchronization. This equation ensures that the combined system-wide reactive power compensation \(\Omega _{i,t}^{\text {react}}\) and phase correction \(\Lambda _{j,t}^{\text {phase}}\) do not exceed the predefined stability threshold \(\Xi ^{\text {stab}}\). This protects the recovering grid from excessive phase misalignment or instability caused by uncoordinated restoration.

Loss minimization is a key objective during black-start. This constraint restricts the total network power loss \(\Theta _{i,j,t}^{\text {loss}}\) and correctional energy dispatch \(\Phi _{k,t}^{\text {corr}}\) to remain within the operational tolerance \(\Psi ^{\text {tolerance}}\). It ensures that energy redistribution is conducted efficiently, preventing excessive waste and ensuring the system remains within its tolerance limits.

In cyber-physical systems, strategic deception mechanisms can improve resilience against targeted attacks. This equation enforces a minimum level of decoy placement \(\Gamma _{q,t}^{\text {decoy}}\) and cyber deception actions \(\Psi _{p,t}^{\text {deception}}\) to reach the minimum security threshold \(\Lambda ^{\text {secure}}\). By incorporating quantum-inspired obfuscation techniques, this constraint ensures that adversaries are misled, preventing effective disruption of black-start operations.

Ensuring a minimum level of energy reserve is critical for system restoration. This constraint guarantees that the total available energy reserves \(\Gamma _{i,t}^{\text {reserve}}\) and allocated energy \(\Lambda _{j,t}^{\text {alloc}}\) meet or exceed the required threshold \(\Psi _{t}^{\text {critical}}\). This ensures that even under uncertain demand fluctuations, the black-start process remains stable and operational.

Too many switching actions and control adjustments can destabilize the system. This equation places a limit on the total number of switching operations \(\Theta _{i,j,t}^{\text {switch}}\) and control adjustments \(\Phi _{k,t}^{\text {adjust}}\), ensuring they remain within the safe operational range \(\Xi _{t}^{\text {oper}}\). This prevents unnecessary oscillations in the system’s reconfiguration process.

Grid rejoining constraints are necessary to prevent unstable reconnections. This equation ensures that the rejoining of islanded subsystems, represented by \(\Gamma _{i,t}^{\text {island}}\) and \(\Lambda _{j,t}^{\text {island}}\), remains within the controlled threshold \(\Psi ^{\text {rejoin}}\). The gradual reintegration of disconnected components minimizes instability and ensures system-wide synchronization.

Preventing cascading failures is essential in black-start recovery. This constraint ensures that line stress levels \(\Theta _{i,j,t}^{\text {stress}}\) and sudden load injections \(\Psi _{m,t}^{\text {load}}\) do not exceed the failure limit \(\Xi ^{\text {failure}}\). By imposing this limit, the risk of overloading transmission elements and destabilizing system operations is significantly reduced.

System stability in terms of frequency and voltage must be actively maintained. This constraint ensures that the total frequency control actions \(\Phi _{p,t}^{\text {freq}}\) and voltage stabilization efforts \(\Gamma _{q,t}^{\text {voltage}}\) meet or exceed the minimum stability requirement \(\Lambda ^{\text {stability}}\). This guarantees that the grid remains resilient against fluctuations as the black-start process unfolds.

Fault tolerance and corrective actions must be managed within acceptable limits. This constraint ensures that fault impact \(\Xi _{i,j,t}^{\text {fault}}\) and corrective interventions \(\Psi _{k,t}^{\text {correct}}\) remain within the manageable threshold \(\Theta ^{\text {repair}}\). By maintaining this bound, the grid can dynamically adapt to unexpected failures while continuing the black-start process.

Ensuring an immediate response to energy demands during black-start is vital. This constraint enforces a minimum reserve margin \(\Gamma _{i,t}^{\text {reserve}}\) and a responsive energy dispatch \(\Lambda _{j,t}^{\text {response}}\) that together must exceed a pre-defined critical response threshold \(\Psi ^{\text {critical}}\). This ensures rapid adaptability to unexpected fluctuations in demand.

Energy transfers must be constrained to prevent system overload. This equation limits the combined power transfers \(\Theta _{i,j,t}^{\text {transfer}}\) and redispatch operations \(\Phi _{m,t}^{\text {redispatch}}\) to a maximum overload tolerance \(\Xi ^{\text {overload}}\). This prevents excessive stress on the transmission system and ensures safe operational limits.

The process of reintegrating islanded subsystems must be gradual. This constraint ensures that the controlled rejoining of islanded nodes \(\Omega _{i,t}^{\text {islanding}}\) and reconnection attempts \(\Psi _{j,t}^{\text {reconnection}}\) stay within an allowable limit \(\Lambda ^{\text {rejoin}}\). This prevents system-wide synchronization issues and ensures smooth integration.

Frequency and voltage imbalances must remain within a safe tolerance. This equation limits the sum of all power imbalances \(\Theta _{i,j,t}^{\text {imbalance}}\) and balancing actions \(\Phi _{p,t}^{\text {balancing}}\) to the predefined system tolerance \(\Xi ^{\text {tolerance}}\). This guarantees stability in the black-start process.

Cyber-physical security measures must be actively deployed. This constraint ensures that the total cyber-defense resources \(\Gamma _{q,t}^{\text {defense}}\) and physical protection efforts \(\Psi _{r,t}^{\text {protection}}\) exceed a minimum required security threshold \(\Lambda ^{\text {security}}\). This ensures resilience against potential cyber and physical threats.

Faults and failures must be promptly addressed. This constraint ensures that the accumulated fault level \(\Xi _{i,t}^{\text {fault}}\) and corrective repair actions \(\Theta _{j,t}^{\text {repair}}\) remain within the maximum allowed recovery threshold \(\Psi ^{\text {recovery}}\). This facilitates rapid fault resolution, ensuring smooth system restoration.

Dynamic grid adjustments must be regulated to maintain stability. This equation ensures that the total dynamic topology changes \(\Theta _{i,j,t}^{\text {dynamic}}\) and adaptive energy dispatch \(\Psi _{m,t}^{\text {adaptive}}\) do not exceed the predefined stability threshold \(\Xi ^{\text {stability}}\). This prevents excessive fluctuations in the system during black-start recovery.

Accurate forecasting of energy availability is crucial for optimizing black-start operations. This constraint ensures that predictive models for power injection \(\Gamma _{p,t}^{\text {forecast}}\) and system-wide predictions \(\Phi _{q,t}^{\text {prediction}}\) meet or exceed a minimum accuracy threshold \(\Lambda ^{\text {accuracy}}\). This guarantees reliable energy estimates for efficient restoration.

Resilience must be actively reinforced in the energy storage system. This constraint ensures that resilience-enhancing efforts \(\Xi _{i,t}^{\text {resilience}}\) and network fortification \(\Theta _{j,t}^{\text {fortification}}\) exceed the critical reinforcement threshold \(\Psi ^{\text {reinforcement}}\). This ensures the black-start network remains robust against adverse conditions.

Network coordination and synchronization must be controlled. This equation ensures that the total cross-node coordination efforts \(\Lambda _{i,j,t}^{\text {coordination}}\) and real-time synchronization actions \(\Psi _{m,t}^{\text {synchronization}}\) remain within the system coherence threshold \(\Xi ^{\text {coherence}}\). This prevents misalignment in energy dispatch sequences.

Quantum-assisted optimization plays a key role in black-start operations. This constraint ensures that the total quantum-enhanced optimization \(\Gamma _{p,t}^{\text {quantum}}\) and annealing-driven dispatch strategies \(\Phi _{q,t}^{\text {annealing}}\) meet or exceed the required quantum optimization threshold \(\Lambda ^{\text {qopt}}\). This allows faster and more efficient black-start solutions.

Hybrid energy systems must be well-integrated for smooth black-start recovery. This constraint ensures that the total hybrid resource dispatch \(\Theta _{i,t}^{\text {hybrid}}\) and multi-modal energy exchanges \(\Psi _{j,t}^{\text {multi-modal}}\) remain within the integration threshold \(\Xi ^{\text {integration}}\). This prevents compatibility issues between different energy sources.

Fail-safe mechanisms must be in place to handle worst-case scenarios. This constraint ensures that backup energy availability \(\Gamma _{p,t}^{\text {backup}}\) and emergency fail-safe measures \(\Phi _{q,t}^{\text {fail-safe}}\) exceed the necessary fallback threshold \(\Lambda ^{\text {fallback}}\). This allows for continued operation even under extreme contingencies.

Energy storage networks must incorporate modernized control strategies. This constraint ensures that the sum of all innovation-driven operational strategies \(\Xi _{i,t}^{\text {innovation}}\) and network advancements \(\Theta _{j,t}^{\text {advancement}}\) exceed the predefined modernization threshold \(\Psi ^{\text {modernization}}\). This ensures black-start operations continue evolving with emerging technologies.

Self-learning and adaptive optimization must be enforced. This constraint ensures that learning-driven optimization \(\Lambda _{p,t}^{\text {learning}}\) and adaptive response strategies \(\Phi _{q,t}^{\text {adaptive}}\) exceed the self-optimization threshold \(\Xi ^{\text {self-optimization}}\). This promotes continuous improvement in energy restoration methods.

Grid-forming capabilities must be leveraged during black-start. This constraint ensures that the total grid-forming energy control \(\Gamma _{i,j,t}^{\text {grid-forming}}\) and island stability measures \(\Psi _{k,t}^{\text {island-stability}}\) meet or exceed the minimum grid support threshold \(\Lambda ^{\text {grid-support}}\). This ensures continued operation in isolated conditions.

Results

The case study is conducted on a synthetic yet realistic large-scale power grid model, designed to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed quantum topological optimization framework for black-start operations in network-type energy storage systems (ESS). The test system consists of 300 buses, 450 transmission lines, and 120 distributed ESS units, strategically placed across the network to provide decentralized black-start support. To focus on evaluating the topological optimization capabilities of the proposed framework, the synthetic grid model adopts idealized renewable generation profiles and static load demands. These simplifications allow for isolating the effects of network reconfiguration strategies without introducing additional stochastic variability. The total system demand is set at 15,000 MW, with an initial blackout condition affecting 90% of the network, requiring a full restoration strategy. The ESS units vary in capacity, with 60 large-scale storage units (ranging from 50 MWh to 200 MWh) and 60 small-scale units (ranging from 10 MWh to 50 MWh) integrated into microgrids. These ESS units are modeled with charging and discharging efficiencies of 92% and 90%, respectively. Renewable generation, including 150 solar farms (total capacity: 8,000 MW) and 80 wind farms (total capacity: 6,500 MW), is included to simulate a realistic modern grid with high penetration of intermittent resources. The time resolution for black-start simulations is set to 10-minute intervals, with a total recovery horizon of 6 hours for full restoration. All performance evaluations were conducted based on 30 independent simulation runs for each restoration strategy and disruption scenario. The simulation trials cover natural disaster events, cyber-physical attacks, and stochastic failures with varying severity levels. Reported performance metrics-such as restoration time, ESS utilization, and resilience scores-represent average values across these multiple trials. Additionally, confidence intervals at a 95% level were estimated to assess result consistency, further demonstrating the robustness of the proposed framework under diverse failure conditions.

The computational environment for this study leverages a hybrid quantum-classical computing approach, integrating D-Wave Advantage quantum annealers with classical high-performance computing (HPC) systems. The quantum topological optimization component is executed using D-Wave Ocean SDK, specifically employing Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) and Quantum Graph Partitioning (QGP) methods for optimizing ESS reconfiguration and network resilience under black-start conditions. The classical computation component runs on a 64-core AMD EPYC 7742 server with 1 TB of RAM, handling the deterministic power flow calculations, AC optimal power flow (AC-OPF) verification, and transient stability analysis. Quantum computations are performed on a D-Wave Advantage 5000Q system with over 5,000 qubits, used primarily for solving large-scale combinatorial optimization problems related to network topology restructuring and ESS dispatch sequencing. The interaction between classical and quantum systems is managed through a quantum-inspired hybrid solver, which determines when to offload high-complexity optimization tasks to the quantum processor.

To ensure realistic system dynamics, the black-start process is simulated under three distinct failure scenarios: (i) natural failure (e.g., cascading grid failure due to extreme weather), (ii) cyber-physical attack (targeted ESS and substation disruption), and (iii) randomized failure propagation (stochastic failure propagation mimicking real-world grid collapse scenarios). For each scenario, the system restoration strategy is evaluated based on total recovery time, energy redistribution efficiency, and network resilience metrics, with a focus on minimizing voltage violations, frequency instabilities, and suboptimal energy dispatch. The results are compared against benchmark black-start optimization models, including mixed-integer linear programming (MILP), heuristic-based restoration, and classical graph-theoretic network reconfiguration methods. The performance metrics include (i) recovery time reduction (% improvement over benchmarks), (ii) optimized ESS utilization efficiency (% of available storage effectively used), and (iii) network resilience score (quantifying resistance to cascading failures and cyber intrusions). The integration of quantum graph theory in this study provides a significant computational speedup, reducing black-start decision times by an estimated 40–50% compared to classical methods, demonstrating the scalability and robustness of the proposed quantum-enhanced optimization framework. To further characterize the failure scenarios quantitatively, we define disruption intensity parameters for each case. For natural failures, random area-based outages affect 10–30% of critical nodes. For cyber-physical attacks, disruptions propagate at a rate of approximately 5–10% of nodes per minute. For stochastic failures, each node faces an independent failure probability between 5% and 15%. These parameter settings allow preliminary evaluation of the framework’s robustness under varying disruption severities.

To provide a clear overview of the computational workflow, we summarize the entire case study process in a structured five-step diagram, as shown in Figure 1. This framework integrates quantum optimization with classical simulation to support resilient black-start planning using distributed ESS. Each stage reflects a distinct functional layer within the hybrid decision-making loop.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the proposed workflow consists of five interconnected stages that together support quantum-classical hybrid optimization for black-start restoration. The process begins with Data Collection, where critical system inputs-including ESS parameters, network topology, and representative failure scenarios-are gathered to define the operational environment. In the Data Preprocessing step, raw information is standardized and structured into quantum-compatible formats, including the construction of constraint matrices and decision variables suitable for annealing-based optimization. Next, the Quantum Optimization module performs combinatorial search over ESS dispatch sequences and reconfiguration paths using quantum annealing techniques. This stage identifies candidate solutions aimed at minimizing system recovery time while satisfying structural and resilience-related constraints. These solutions are then passed into the Simulation and Evaluation stage, where classical AC optimal power flow (AC-OPF) simulations are executed to verify feasibility, assess voltage and frequency stability, and validate operational limits under the given scenario. Finally, the Optimization Integration step consolidates the evaluated results into a deployable restoration strategy. This includes refining the dispatch plan, applying constraint-based adjustments, and finalizing ESS activation schedules for implementation. The looped structure of the workflow allows for iterative feedback between classical validation and quantum search refinement, ultimately converging on a solution that balances optimization quality with physical system integrity.

Figure 2 provides a high-resolution spatial mapping of the case study’s power grid, including 300 buses, 450 transmission lines, 120 energy storage systems (ESS), 150 solar farms, and 80 wind farms. The transmission lines, represented by light gray connections, outline the backbone of the network, demonstrating the complexity of inter-bus energy flow. The buses are displayed in light blue, with the size of each marker scaled according to its energy demand, ranging between 10 MW and 100 MW. The network is strategically designed to ensure that buses with higher demand density are closer to energy storage systems (ESS) for optimized restoration during black-start operations. The ESS units, marked in deep navy, are geographically distributed across the network with capacity variations of 50 MWh, 100 MWh, and 200 MWh, ensuring a balanced power reserve to support recovery efforts. The renewable generation facilities, consisting of solar farms (gold) and wind farms (gray), reflect an installed capacity of 8,000 MW from solar energy and 6,500 MW from wind power, contributing significantly to grid recovery strategies. The spatial arrangement of energy storage systems and renewables is crucial for enhancing grid resilience and optimizing black-start procedures. The ESS units are distributed in a non-uniform pattern, with clusters appearing in areas of high network importance to facilitate rapid power injection during black-start. The visualization reveals that nearly 40% of ESS units are positioned near major transmission hubs, while the remaining 60% are allocated to peripheral regions, ensuring decentralized backup power support. This distribution allows for localized microgrid operation in case of prolonged transmission failures. The solar and wind farms are strategically positioned to maximize geographical efficiency, with solar capacity primarily concentrated in the central and southern regions, where irradiance levels are higher, and wind capacity spread toward the northern and coastal areas, benefiting from stronger and more consistent wind speeds. The size of each solar and wind farm marker is proportional to its generation capacity, with values ranging from 20 MW to 150 MW, enabling a realistic representation of renewable contributions to the black-start process.

Figure 3 provides a detailed statistical overview of the capacity distribution for energy storage systems (ESS), solar farms, and wind farms in the case study. The x-axis represents capacity ranges in MW/MWh, while the y-axis indicates the number of units falling into each category. The energy storage systems (ESS) exhibit three primary capacity levels: 50 MWh, 100 MWh, and 200 MWh, with the highest concentration in the 100 MWh range, accounting for nearly 45% of all ESS units. This highlights the system’s focus on mid-scale storage, ensuring sufficient energy reserves for rapid power injection during black-start. Meanwhile, the solar farm distribution peaks at 50 MW, representing about 40% of the solar units, whereas wind farms have a higher mean capacity, with 100 MW and 150 MW wind sites dominating the dataset. The variation in storage and generation sizes reflects a balanced approach, where both decentralized microgrid-level resources and larger grid-scale units are integrated for resilience. A closer look at the distribution trends reveals key planning implications for black-start optimization. The clustering of 100 MWh ESS units suggests that the system has been designed with an emphasis on medium-duration energy reserves, which are well-suited for progressive power restoration rather than immediate, short-term surges. The presence of larger 200 MWh ESS units, although fewer in number, plays a strategic role in sustaining grid stability during prolonged black-start scenarios. On the generation side, the solar farm capacity distribution indicates a preference for moderate-scale installations over high-concentration solar hubs, suggesting a decentralized planning approach to mitigate intermittency risks. Wind farms, on the other hand, show a heavier concentration in the 100–150 MW range, underscoring their role as backbone generators for sustained recovery phases. This differentiation in renewable asset distribution ensures that the system maintains both rapid response capability (via ESS) and continuous power injection (via wind farms).

Figure 4 presents a geospatial visualization that integrates energy storage systems (ESS), solar farms, wind farms, and the demand distribution across the power grid. The heatmap, shown in blue, represents the demand at each bus location, where darker shades correspond to higher demand values (ranging from 10 MW to 100 MW). The ESS units are represented in dark blue, with their size proportional to their storage capacity, varying from 50 MWh to 200 MWh. The solar farms and wind farms are shown in gold and gray, respectively, with their marker size reflecting the capacity of each renewable generator, ranging from 20 MW to 150 MW. This map provides an intuitive understanding of how energy storage and renewable generation are distributed in relation to demand, helping to identify areas where grid support is most needed. In this visualization, the hexbin heatmap is used to depict demand intensity, showing higher power demand clusters near the center of the grid, where the grid might experience the most stress during a black-start event. The energy storage systems (ESS) are strategically placed around areas with higher demand density, ensuring that power can be rapidly injected into the grid when needed. This distribution suggests that energy storage is used as a buffer to balance fluctuations between renewable generation and demand. The solar farms, concentrated in areas with better sun exposure, and the wind farms, located in regions with higher wind availability, are positioned to maximize their generation potential. Both renewable resources provide critical sustained energy generation to support grid recovery, particularly in cases where short-term storage is insufficient for complete recovery.

Figure 5 presents a time-series analysis of energy storage utilization during a simulated black-start event, covering a 6-hour recovery window with 10-minute intervals. The three lines represent different energy storage system (ESS) capacities: high-capacity (200 MWh, dark blue), mid-capacity (100 MWh, medium blue), and small-capacity (50 MWh, light blue). The discharge profile illustrates how each storage unit depletes over time, with the high-capacity ESS maintaining output for a longer period, ensuring sustained grid support, while smaller storage units exhaust their reserves earlier. Initial fluctuations in the curves reflect dynamic power dispatch strategies, where storage resources adjust to real-time demand variations during system restoration. Analyzing the discharge rates, the high-capacity ESS starts at 200 MWh and steadily depletes at an approximate rate of 30 MWh per hour, maintaining a meaningful contribution until around the 5-hour mark, after which reserves are critically low. The mid-capacity ESS starts at 100 MWh and discharges at approximately 20 MWh per hour, fully depleting within about 4.5 hours. The small ESS (50 MWh) depletes the fastest, with a discharge rate of about 10 MWh per hour, running out of energy just after 3 hours. This pattern demonstrates that while smaller ESS units provide an immediate boost to early recovery, the high-capacity units are essential for sustained support throughout the black-start process.

Figure 6 illustrates the percentage of the power grid that has been successfully restored during a black-start event, plotted over a 6-hour recovery window. The recovery follows a characteristic exponential trend, with a rapid initial restoration phase followed by a gradual saturation effect as the remaining sections of the grid become more challenging to recover. In the first 1.5 hours, nearly 40% of the grid is restored, primarily due to the fast deployment of energy storage systems (ESS) and pre-identified restoration pathways. By the 3-hour mark, the recovery has reached 70%, as energy redistribution and voltage stabilization mechanisms take full effect. The final 20–30% of the grid takes the longest to recover, as it involves the reintegration of complex transmission corridors and smaller microgrid regions that require synchronized reconnection to avoid instability. Minor fluctuations of ±2% throughout the curve indicate real-time adaptation to network constraints, reflecting the dynamically optimized quantum topological framework used in this study. One of the most critical takeaways from this figure is the significant reduction in recovery time compared to traditional black-start methods. Conventional optimization models often require 8 to 12 hours to restore 90% of the system, whereas the proposed quantum-enhanced approach achieves this in approximately 5 hours. This improvement is attributed to efficient storage dispatching, optimized ESS placement, and adaptive energy re-routing, all of which enable faster and more strategic system recovery. The rapid early-stage recovery is largely driven by pre-positioned high-capacity ESS and quantum-assisted network reconfiguration, which identify the most effective restoration sequences in real-time. As the final segments of the grid are re-energized, constraints related to load balancing, frequency stability, and phase synchronization become dominant, necessitating a slower, more controlled recovery approach.

Figure 7 highlights the critical role of energy storage systems (ESS) in facilitating black-start recovery, illustrating the total amount of energy discharged over time. The discharge profile follows a characteristic declining trajectory, beginning at 200 MWh and gradually tapering off as ESS reserves are depleted. In the first 3 hours, over 120 MWh is discharged, accounting for nearly 60% of the total available energy. The energy supply rate then slows down in the final 3 hours, with the remaining 80 MWh strategically allocated to support voltage and frequency stabilization as additional power sources come online. This discharge pattern reflects a well-optimized multi-phase ESS utilization strategy, ensuring high availability during critical early-stage recovery while preserving reserves for fine-tuned system stabilization later in the process. One of the most notable trends in this figure is the adaptive discharge rate observed throughout the recovery window. Unlike traditional black-start methodologies, which often rely on fixed-rate ESS discharge, the proposed model dynamically adjusts energy output based on real-time grid conditions. This enables an optimal balance between immediate power injection and long-term system sustainability, preventing premature depletion while maximizing grid support. The observed discharge variations suggest that storage units are strategically coordinated, with high-capacity ESS prioritizing early-stage recovery, while mid-capacity and smaller units take over in later phases. This ensures a continuous supply of stable power, mitigating the risks associated with ESS exhaustion before full recovery is achieved.

Figure 8 illustrates the relative contributions of different energy storage system (ESS) sizes to total grid recovery during black-start. The results show that large ESS units (200 MWh) provide 45% of the total black-start energy, while medium-sized ESS (100 MWh) contributes 35%, and smaller ESS units (50 MWh) contribute 20%. This distribution reflects a hierarchical storage deployment strategy, where large-scale ESS plays a foundational role in sustaining grid recovery, while smaller units serve as rapid-response stabilizers in the initial restoration phases. The dominance of large-scale ESS in energy contribution is expected, as these units are designed to provide long-duration power support, allowing time for renewable energy sources and traditional generators to stabilize the system. The mid-sized ESS (100 MWh) acts as an intermediary buffer, bridging the gap between immediate power injection and longer-term energy balancing. Small-scale ESS, while contributing the least (20%), is essential in providing instant power for critical loads, helping to stabilize frequency and voltage in the early minutes of black-start restoration.

Figure 9 presents a regional breakdown of renewable energy contributions, showing the relative proportions of solar and wind power in three key geographic zones (North, Central, South). The results reveal that solar energy plays the most significant role in the Central region (45%), while wind power dominates in the South (50%). The Northern region maintains a relatively balanced mix, with solar and wind contributing 30% and 40%, respectively. The variability in renewable energy contributions across regions is driven by geographical and climatic factors. The Central region’s higher solar contribution (45%) suggests that it benefits from more stable solar irradiance, making it an ideal hub for solar farms. In contrast, the South has the highest wind contribution (50%), indicating that stronger wind currents are present, supporting the deployment of high-capacity wind farms. The North maintains a more balanced mix, which enhances regional resilience by reducing dependence on a single energy source. This regional distribution highlights the importance of spatially optimized renewable deployment in ensuring grid flexibility and resilience. By diversifying energy generation across different renewable sources, the system can minimize supply variability and enhance energy security during black-start events. The ability to dynamically integrate wind and solar contributions into the restoration sequence further supports the efficiency of the proposed optimization model, ensuring that the grid recovers with minimal reliance on fossil-fuel-based black-start generators. This reinforces the role of renewables as primary enablers of resilient and sustainable power restoration strategies.

Figure 10 presents a high-resolution 3D visualization of voltage recovery dynamics across different grid nodes over a 6-hour black-start period. The plot exhibits a smooth, structured recovery progression that accurately reflects the mathematically coordinated stabilization of voltage levels. Unlike raw data visualizations with noise or abrupt fluctuations, this figure provides a clear, continuous representation of how voltage levels evolve during black-start, ensuring a scientifically rigorous depiction of the restoration process. The X-axis represents time in hours, illustrating the gradual recovery from initial system instability to full grid re-energization. The Y-axis represents 60 different grid nodes, each experiencing a unique voltage trajectory depending on its position in the network. The Z-axis, showing voltage in per-unit (p.u.), varies within a controlled range of 0.96 to 1.04, ensuring that voltage deviations remain within operational safety margins. The voltage recovery trajectories demonstrate progressive re-energization of the network, with voltages gradually returning to nominal levels through organized, stable pathways. While minor oscillatory patterns are observed-reflecting dynamic synchronization among nodes-no significant large-amplitude sinusoidal oscillations appear at the system level. The color gradient further enhances interpretability, with red regions indicating higher voltage levels and blue regions reflecting lower deviations, providing an intuitive understanding of the system’s stability evolution over time.

Figure 11 presents the voltage stabilization process across grid nodes over a 6-hour black-start period, revealing a structured, exponentially damped sinusoidal trend. The X-axis represents time (hours), the Y-axis represents 80 grid nodes, and the Z-axis represents voltage levels in per-unit (p.u.), varying between 0.97 and 1.03 p.u. The voltage recovery follows an initially unstable period with oscillatory fluctuations, which gradually settle into a steady-state condition as the restoration process progresses. The presence of sinusoidal patterns across the nodes highlights the impact of spatial differences in energy dispatch and load balancing, where certain nodes experience a faster return to stable voltage conditions, while others require additional time for full synchronization. The active power dispatch trajectories of distributed ESS units during restoration exhibit corresponding dynamic fluctuations, reflecting decentralized energy reallocation efforts among ESS units in response to evolving load demands and grid stability requirements. The exponential decay observed in the first two hours of recovery suggests that the proposed quantum-assisted black-start method effectively minimizes voltage deviations and ensures a controlled restoration sequence. By the 4-hour mark, nearly all nodes converge towards the operational setpoint of 1.00 p.u., demonstrating the effectiveness of reactive power management and adaptive restoration planning. The spatial variation in the voltage response observed across the Y-axis further indicates that nodes connected to high-capacity energy storage units or key transmission corridors experience earlier stabilization, while peripheral nodes, which may rely on more distributed restoration efforts, stabilize slightly later. The visualization successfully captures the dynamic adaptation of voltage levels and ensures that the black-start methodology prevents excessive transients that could lead to system-wide instability. This structured approach to voltage restoration confirms that the proposed model enhances grid robustness, reduces voltage collapse risks, and optimally allocates reactive power to achieve a seamless transition from blackout to full grid operation.

Figure 12 illustrates the power dispatch strategy across the grid during black-start recovery, focusing on energy allocation from storage units and generators. The X-axis represents time in hours, Y-axis represents 80 grid nodes, and Z-axis represents power dispatch in MW, following a sinusoidal wave pattern with an exponential decay component. Initially, power dispatch experiences significant oscillations, caused by sudden load fluctuations and varying restoration priorities across different sections of the grid. These mild oscillations are attributed to transient synchronization behaviors between gradually reconnected loads and distributed generation resources, reflecting the system’s dynamic adaptation toward full operational stability. The structured nature of the dispatch pattern reflects the adaptive optimization mechanism embedded in the quantum-assisted black-start methodology, ensuring that energy is injected into the system in a staged and controlled manner to prevent grid congestion and overloads. A notable observation in the figure is the higher initial power dispatch levels, which gradually taper off as additional generation units come online, reducing the burden on storage-based energy supply. The power injection rate is highest in the first 1.5 hours, reaching a peak of approximately 115 MW, before declining toward 100 MW as stabilization progresses. This behavior aligns with the need for rapid energy deployment at the onset of black-start, followed by a phase of controlled load management. The sinusoidal nature of the power dispatch response suggests that different regions of the grid are restored at different intervals.

To provide a comprehensive validation of the proposed method’s advantages over traditional restoration approaches, Table 1 summarizes the comparative performance metrics, including computation time, average restoration time, ESS utilization rate, and resilience scores across different optimization strategies.

As shown in Table 1, the proposed quantum-classical hybrid approach significantly reduces computation time and restoration duration while achieving higher ESS utilization rates and superior resilience scores compared to MILP-based and heuristic restoration methods. This comparative analysis further validates the advantages of integrating quantum optimization techniques into resilient black-start planning.

To demonstrate the advantages of the proposed quantum-assisted dynamic reconfiguration strategy, Table 2 compares the black-start restoration performance across multiple restoration strategies.

As observed, the proposed strategy achieves faster restoration times, higher ESS utilization, and superior resilience scores compared to fixed-sequence and priority-based load restoration methods. These results confirm the benefits of employing dynamic and adaptive optimization approaches enabled by quantum-assisted methodologies for resilient black-start planning.

To further evaluate the robustness and adaptability of the proposed framework, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by varying the severity of disruption scenarios. Three different levels of failure intensity-mild, moderate, and severe-were simulated, corresponding to increasing proportions of grid components being initially disrupted. Table 3 summarizes the restoration performance metrics under these different conditions.

The results demonstrate that although restoration time slightly increases and resilience scores marginally decline as disruption severity escalates, the proposed framework consistently maintains high performance levels. This confirms its robust adaptability under a wide range of failure conditions, thereby validating its potential effectiveness for resilient black-start planning in dynamic and uncertain operating environments.

To improve the interpretability of simulation outcomes and facilitate cross-scenario comparisons, Table 4 provides a consolidated summary of key performance metrics across the different disruption types simulated in this study.

As shown in Table 4, the proposed framework achieves consistent performance across different types of disruptions, with minimal variation in restoration time and resilience scores. This further confirms the generalizability and robustness of the method under heterogeneous failure conditions.

Limitations and future challenges

While the proposed quantum-enhanced topological optimization framework demonstrates promising capabilities for black-start restoration planning, certain limitations must be acknowledged to provide a balanced assessment. First, the framework inherently depends on the capabilities of current quantum computing hardware, particularly quantum annealers. Constraints such as limited qubit counts, sparse inter-qubit connectivity, environmental noise susceptibility, and the need for minor embedding limit the scalability of the optimization approach for extremely large-scale power systems. Additionally, although quantum annealing accelerates combinatorial searches, the hybrid quantum-classical iterative workflow introduces considerable computational overhead, as repeated quantum optimization, AC-OPF validation, and constraint refinement cycles are required. This overhead may pose challenges for real-time restoration in large, highly dynamic networks. Future improvements in quantum hardware technologies, as well as advancements in hierarchical decomposition and faster quantum-classical interfacing methods, are necessary to enhance the framework’s practical efficiency and scalability.

Moreover, the current threat modeling adopted in the study is based on simplified disruption scenarios, assuming static blackout topologies and predefined fault propagation patterns. In practical settings, cyber-physical attacks, stochastic failures, and cascading disruptions often involve highly dynamic, unpredictable behaviors that require more sophisticated and adaptive modeling techniques. Incorporating real-time threat detection, dynamic resilience assessment, and probabilistic risk modeling into the restoration framework represents an important future research direction. While the present work provides a conceptual foundation for quantum-enabled black-start planning, substantial efforts are still needed to address hardware dependencies, computational costs, and real-world threat complexities before widespread deployment in operational power systems can be realized.

Conclusion

This paper presented a quantum-enhanced topological optimization framework to improve the resilience and efficiency of black-start operations in networked energy storage systems (ESS). By leveraging quantum graph theory and quantum annealing, the proposed approach effectively tackled the challenges of increasing grid complexity, scalability constraints, and cyber-physical vulnerabilities. The optimization model was designed to minimize system restoration time, enhance energy dispatch efficiency, and reinforce grid resilience under both natural failures and deliberate attacks.

Extensive simulations on a large-scale synthetic power grid validated the framework’s effectiveness, showing up to a 50% reduction in decision-making time, improved ESS coordination, and a marked reduction in vulnerability to cyber-physical threats. These results demonstrate the potential of quantum computing as a transformative tool for resilient energy system planning. The proposed methodology offers a promising direction for modernizing black-start strategies and sets the stage for broader integration of quantum algorithms in future power system operations.

Despite the promising performance demonstrated in our simulations, it is important to acknowledge several limitations of the current framework. First, contemporary quantum annealers, such as those developed by D-Wave, face inherent constraints including limited qubit counts, sparse connectivity, susceptibility to environmental noise, and latency during quantum-classical interaction. A typical annealing cycle incurs a computation delay ranging from tens to hundreds of milliseconds, which may limit the real-time applicability of the proposed framework in large-scale or time-critical black-start scenarios. Furthermore, the effective problem size is bounded by the number of coupled qubits and the overhead associated with minor embedding, making it challenging to optimize densely connected models without decomposition. These hardware-related challenges may affect deployment on current-generation platforms, although ongoing advancements in quantum technologies-such as improved coherence times, scalable architectures, and better error mitigation-are expected to progressively mitigate these limitations. Second, the current simulation setup involves several modeling simplifications, including idealized renewable generation profiles and static load demands. In real-world applications, renewable outputs are inherently intermittent, and load profiles are highly time-varying and uncertain. Incorporating dynamic operational conditions, adaptive threat modeling, and real-time grid dynamics into the optimization framework represents an important future research direction. Overall, while the present work lays a conceptual foundation for quantum-enabled resilient power system restoration planning, substantial further development is required to bridge the gap between synthetic simulations and real-world deployment.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to conflict of interest but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gruber, K., Gauster, T., Laaha, G., Regner, P. & Schmidt, J. Profitability and investment risk of Texan power system winterization. Nature Energy 7(5), 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-022-00994-y (2022) (2022/05/01).

Khazaei, J. & Amini, M. H. Protection of large-scale smart grids against false data injection cyberattacks leading to blackouts. International Journal of Critical Infrastructure Protection 35, 100457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcip.2021.100457 (2021) (2021/12/01/).

Busby, J. W. et al. Cascading risks: Understanding the 2021 winter blackout in Texas. Energy Research & Social Science 77, 102106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102106 (2021) (2021/07/01/).

Li, Y., Zhang, H., Liang, X. & Huang, B. Event-Triggered-Based Distributed Cooperative Energy Management for Multienergy Systems. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 15(4), 2008–2022. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2018.2862436 (2019).

Li, X., Hu, C., Luo, S., Lu, H., Piao, Z. & Jing, L. Distributed Hybrid-Triggered Observer-Based Secondary Control of Multi-Bus DC Microgrids Over Directed Networks, IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers, pp. 1-14, (2025), https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSI.2024.3523339.

Li, Y. et al. Digital Twin for Secure Peer-to-Peer Trading in Cyber-Physical Energy Systems. IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering 12(2), 669–683. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSE.2024.3507956 (2025).

Blekos, K. et al. A review on quantum approximate optimization algorithm and its variants. Physics Reports 1068, 1–66 (2024).

Zhao, N., Zhang, H., Yang, X., Yan, J. & You, F. Emerging information and communication technologies for smart energy systems and renewable transition. Advances in Applied Energy 9, 100125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adapen.2023.100125 (2023) (2023/02/01/).

Ullah, M. H., Eskandarpour, R., Zheng, H. & Khodaei, A. Quantum computing for smart grid applications. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 16(21), 4239–4257 (2022).

Wu, G. & Li, Z. S. Cyber-Physical Power System (CPPS): A review on measures and optimization methods of system resilience. Frontiers of Engineering Management 8(4), 503–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42524-021-0163-3 (2021) (2021/12/01).

Devanny, J., Goldoni, L. R. F. & Medeiros, B. P. The 2019 Venezuelan blackout and the consequences of cyber uncertainty. Revista Brasileira de Estudos de Defesa 7(2), (2020).

Olujobi, O. J. The legal sustainability of energy substitution in Nigeria’s electric power sector: renewable energy as alternative. Protection and Control of Modern Power Systems 5(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41601-020-00179-3 (2020) (2020/12/01).

Hu, Z., Su, R., Zhang, K., Wang, R. & Ma, R. Resilient Frequency Estimation for Renewable Power Generation Against Phasor Measurement Unit and Communication Link Failures. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs 72(1), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2024.3496192 (2025).

Zhao, P., Li, S., Cao, Z., Hu, P. J.-H., Zeng, D. D., Xie, D., Shen, Y., Li, J. & Luo, T. A Social Computing Method for Energy Safety, Journal of Safety Science and Resilience, 2024/01/12/ (2024), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnlssr.2023.12.001.

Li, S. et al. Online battery-protective vehicle to grid behavior management. Energy 243, 123083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.123083 (2022) (2022/03/15/).

Shang, Y., Li, D., Li, Y. & Li, S. Explainable spatiotemporal multi-task learning for electric vehicle charging demand prediction. Applied Energy 384, 125460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2025.125460 (2025) (2025/04/15/).

Bitirgen, K., & Filik, Ü. B. A hybrid deep learning model for discrimination of physical disturbance and cyber-attack detection in smart grid, International Journal of Critical Infrastructure Protection, vol. 40, p. 100582, 2023/03/01/ (2023), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcip.2022.100582.

Anubi, O. M. & Konstantinou, C. Enhanced Resilient State Estimation Using Data-Driven Auxiliary Models. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 16(1), 639–647. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2019.2924246 (2020).

Munikoti, S., Lai, K. & Natarajan, B. Robustness assessment of hetero-functional graph theory based model of interdependent urban utility networks. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 212, 107627 (2021).

Bartolucci, S. et al. Fusion-based quantum computation. Nature Communications 14(1), 912 (2023).

Amani, F., & Kargarian, A. Quantum Optimization for Energy Management: A Coherent Variational Approach, arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.14095, 2024/01/01/ (2024).

Soltaninia, M. & Zhan, J. Quantum Neural Networks for Solving Power System Transient Simulation Problem, arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.11427, 2024/05/20/ (2024).

Coccia, M., Roshani, S. & Mosleh, M. Evolution of quantum computing: Theoretical and innovation management implications for emerging quantum industry, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, (2022).

De Leon, N. P. et al. Materials challenges and opportunities for quantum computing hardware. Science 372(6539), eabb2823 (2021).

Iwabuchi, K. et al. Enhancing grid stability in PV systems: A novel ramp rate control method utilizing PV cooling technology. Applied Energy 378, 124737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.124737 (2025).

Zhao, D., Onoye, T., Taniguchi, I. & Catthoor, F. Transient Response and Non-Linear Capacity Variation Aware Unified Equivalent Circuit Battery Model, *ResearchGate*, (Dec. 2022). [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366215648_Transient_Response_and_Non-Linear_Capacity_Variation_Aware_Unified_Equivalent_Circuit_Battery_Model

Li, Y., Hu, C., Luo, S., Lu, H., Piao, Z., & Jing, L. Distributed Hybrid-Triggered Observer-Based Secondary Control of Multi-Bus DC Microgrids Over Directed Networks, *IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers*, pp. 1-14, (2025), https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSI.2024.3523339.

Shang, Y., Li, D., Li, Y. & Li, S. Explainable spatiotemporal multi-task learning for electric vehicle charging demand prediction. Applied Energy 384, 125460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.125460 (2025).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Project of the State Grid Corporation of China (Grant No. B3018 K24006 C).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yinchi Shao, Yu Gong, Xiaoyu Wan, Xianmiao Huang: Responsible for the practical engineering problem definition, industrial background, data support, and validation of the proposed model in real-world mining scenarios. Shanna Luo (corresponding author): Conceptualized the academic framework, contributed to the methodology and writing of the manuscript, and coordinated the collaborative research effort. Yuntao Cao, Tao Zhang: Assisted in model formulation, algorithm design, and sensitivity analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions