Abstract

Coal and gas outbursts pose significant risks to underground mining operations, and accurate and reliable prediction is crucial for improving mine safety. Traditional machine learning models struggle to balance prediction accuracy and interpretability, particularly in cases of limited data or complex geological conditions. To address this challenge, this study proposes a prediction model based on Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINN), which integrates physical monotonicity constraints with data-driven learning to ensure that the predictions align with physical laws. Using actual data from a coal mine, this study compares the performance of the PINN model with traditional machine learning models, including Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN). The results show that the PINN model achieves a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.966 and a root mean square error (RMSE) of 6.452, outperforming the traditional models in both prediction accuracy and generalization ability. Furthermore, interpretability is significantly enhanced by incorporating known physical behaviors and monotonicity constraints. The proposed PINN-based prediction framework provides a more reliable and theoretically grounded approach to assessing coal and gas outburst risks. Integrating it into mining safety management systems can significantly improve early warning mechanisms and risk mitigation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As shallow coal reserves in China become increasingly depleted, coal mining operations have shifted to deeper depths, deteriorating mining conditions. High geological stress, elevated gas content, and severe mining-induced disturbances threaten worker safety and operational efficiency1,2. Consequently, developing precise prediction and early warning methods for coal and gas outbursts is essential for preventing catastrophic incidents and improving coal mine safety management.

Coal and gas outbursts are influenced by complex nonlinear factors, including mining intensity, coal seam gas content, mining depth, and ventilation conditions. To improve prediction accuracy, researchers have explored various computational techniques. Traditional machine learning models have played a significant role in coal and gas outburst prediction. For example, Shao et al.3 employed the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method to address missing data and developed a prediction model based on a Support Vector Machine (SVM) optimized by the Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA). Similarly, Xu et al.4 introduced a novel prediction framework integrating Sparse Kernel Principal Component Analysis (SKPCA) with the Neural Evolution Algorithm (NEAT), demonstrating enhanced predictive precision. Zhou et al.5 further refined machine learning-based approaches using the SSA-Kernel Extreme Learning Machine (SSA-KELM), achieving significant performance gains. Wen et al.6 tackled missing data challenges through a Whale Optimization Algorithm-Extreme Learning Machine (WOA-ELM) model. Additional optimization techniques, such as the Improved Real-coded Quantum Genetic Algorithm (IRQGA) combined with an Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS)7 and a double coupling prediction model incorporating IsoMap and weighted vector machines8 have also been explored.

Beyond traditional machine learning models, hybrid approaches and evolutionary algorithms have been employed to further enhance prediction accuracy. Yang et al.9 developed a coal and gas outburst prediction model using the improved artificial Electric Field Algorithm-Least Square Support Vector Machine (IAEFA-LSSVM), which exhibited resilience against poor data quality. Wang Wei et al.10 extension theory and the fuzzy analytic hierarchy process were applied to assess subjective and objective weighting factors, leading to an improved prediction model. Additionally, Grey Wolf Optimizer-SVM (GWO-SVM)11, multi-factor fuzzy comprehensive evaluation12, and random forest models incorporating the Pauta criterion13 have been employed to refine coal and gas outburst predictions. Furthermore, Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) has been used to identify key influencing factors, leading to the development of the Fuzzy Synthetic Prediction Algorithm (F-SPA)14.

With the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence, deep learning and neural network-based models have emerged as powerful alternatives to traditional methods. Studies have shown that Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) demonstrate superior predictive capabilities in various engineering applications. For instance, Srii Ihssan et al.15 validated the predictive efficiency of Bayesian-regularized ANNs for assessing tensile strength, while Nagoor Basha Shaik et al.16 integrated ANN with Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) for structural health monitoring. In coal mining applications, Monalisa Maiti et al.17 highlighted the advantages of Fractional-Order Neural Networks (FONN) in modeling long-term coal-rock interactions. Similarly, Geleta Warkisa Deressa and Bhanwar Singh Choudhary18 applied Random Forest Regression (RFR) in mining productivity analysis, demonstrating its interpretability using SHAP values. Comparative studies on ANN, Genetic Algorithms (GA), and Multiple Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS)19 have reinforced ANN’s superior performance in coal property predictions. At the same time, Multi-Input Single-Output White Box ANN (MISOWB-ANN) models20 have proven effective for mineral composition forecasting. Moreover, hybrid approaches such as Spotted Hyena Optimization-ANN (SHO-ANN)21 have further enhanced deep learning-based predictions in mining safety assessments. Previous studies have developed various prediction models and trend analyses for coal and gas outbursts using different datasets and algorithms. However, existing outburst prediction models primarily rely on data-driven approaches, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Neural Networks (NN), which often function as “black boxes”, making it difficult to interpret their predictions within the framework of underlying physical mechanisms. Furthermore, these models require large volumes of high-quality training data. However, the variability of geological conditions and the scarcity of historical outburst data significantly limit their applicability in coal and gas outburst prediction.

To overcome these challenges, this study introduces the PINN, which integrates data-driven learning with physics-based constraints. This approach establishes a physics-data hybrid modeling framework by embedding monotonicity constraints into the neural network. It improves predictive accuracy and effectively reveals underlying physical mechanisms, overcoming the "black-box" limitations of traditional models and providing robust support for coal mine safety management.

PINN model

Model construction

N training samples are selected, \(\left\{ {\left( {{\varvec{x}}^{(i)} ,t^{(i)} } \right)} \right\}_{i = 1}^{N} ,i = 1,...,N{,}x^{(i)} \in {\mathbb{R}}^{n}\) is the input vector, t(i) is the output value, and the corresponding model prediction value can be expressed as:

where o(i) denotes the model’s predicted outcome; f(.) signifies the operation performed by the neural network; w is the connection weight between the input and hidden layers; β acts as the weight linking the hidden and output layers; g(.) is the sigmoid activation function; b refers to the bias vector of the hidden layer.

The process of training the neural network involves optimizing the parameters w ,β, and b22,23. The aim of training is to minimize the error Er between the predicted output of the model and the target value, as illustrated in the following equation:

Monotonicity expression

Equation (3) provides the expression for the partial derivative of the output variable o with respect to the input variable xj .In cases where a monotonically increasing relationship exists between o and xj , then \(\frac{\partial o}{{\partial x_{j} }}(x) > 0\),otherwise \(\frac{\partial o}{{\partial x_{j} }}(x) < 0\).

where j = 1, 2, …, n.

The loss function of the PINN model

In traditional neural network training, the model’s loss function is typically defined by the difference between observed and predicted values. During training, all internal parameters of the model are optimized to minimize the loss function. Building on traditional neural networks, this study takes into complete account the prior monotonicity between input and output parameters and introduces a novel PINN modeling approach22. This method adds two additional constraint constraints to the training loss function: structural losses and physical discordance. These details can be seen in Eqs. (4) and (5):

where \(sign(\theta ) = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}c} { - 1,\theta < 0} \\ {1,\theta \ge 0} \\ \end{array} } \right.\); \(x_{{{\text{syn}}}}^{(i)}\) is the manual input part of the i-th recombination sample; \(m_{j}^{(i)}\) is its monotonicity divisor, if the physical monotonicity is positive, then \(m_{j}^{(i)} = 1\), otherwise \(m_{j}^{(i)} = - 1\); \(T_{j}\) represents the number of comprehensive samples that maintain a monotonic relationship between input and output in the j-th dimension.

The physical discordance Ep injects information about monotonicity into the PINN model by creating synthetic samples. Unlike the actual operational data, each composite sample consists of an artificially generated input component xsyn and a specified monotonicity factor m, which contains no output label information. It should be noted that Ep measures the overall physical discordance of the PINN model. A large EP indicates that the internal mechanism of the network seriously deviates from the actual process, and the model’s explanatory power is weak. For example, consider a synthetic sample \(\left( {x_{{{\text{syn}}}}^{(i)} ,m_{j}^{(i)} } \right)\), where \(m_{j}^{(i)} = - 1\), means that the relationship between the input and output of the j-th dimension shows negative monotonicity. In each iterative training of the PINN model, the partial derivative \(\frac{\partial o}{{\partial x_{j} }}(x_{{{\text{syn}}}}^{(i)} )\) of o with respect to xj will be calculated and adjusted. If \(\frac{\partial o}{{\partial x_{j} }}(x_{{{\text{syn}}}}^{(i)} ) > 0\), then \({\text{sign}}(\frac{\partial o}{{\partial x_{j} }}(x_{{{\text{syn}}}}^{(i)} )) = 1\), means that the relationship between the input and output of the j-th dimension shows positive monotonicity in the PINN model. This is inconsistent with the given monotonicity factor \(m_{j}^{(i)} = - 1\). Therefore, according to the formula (5), the Ep corresponding to the synthetic sample \(\left( {x_{{{\text{syn}}}}^{(i)} ,m_{j}^{(i)} } \right)\) is a penalty term in the loss function. If \(\frac{\partial o}{{\partial x_{j} }}(x_{{{\text{syn}}}}^{(i)} ) < 0\), then the corresponding Ep is 0, indicating that \(\frac{\partial o}{{\partial x_{j} }}(x_{{{\text{syn}}}}^{(i)} )\) can match the given monotonicity factor \(m_{j}^{(i)}\) and there is no penalty value in the loss function.

In summary, the loss calculation function of PINN can be denoted as:

where the \(\lambda_{s}\) and \(\lambda_{p}\) represent the weight coefficients of structural losses and physical inconsistency, respectively.

The regression loss Er represents the distance between the measured value and the predicted value, the structural loss Es is the L2 norm of the network weight to decrease the over-fitting of the model, and the physical inconsistency Ep represents the degree of deviation between the model and the physical monotonicity.

PINN model training

Artificial neural networks typically use backward propagating methods to obtain the best network parameters. However, the backward propagating algorithm is unsuitable for the non-differentiable monotonicity constraint in the loss function of the PINN model. Therefore, this study employs the Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) to optimize parameters during the PINN training. CMA-ES is a stochastic, derivative-free evolutionary algorithm well-suited for non-convex and complex optimization problems. It adapts the covariance matrix of a multivariate normal distribution to efficiently explore the search space and improve convergence stability in high-dimensional scenarios. The Training Procedure for PINN Utilizing CMA-ES22 is summarized here.

Step 1 Determine the quantity of nodes present in the hidden layer of the PINN based on the specific training dataset. In this study, the hidden layer of the coal and gas outburst prediction model is configured to contain two nodes.

Step 2 Initialize the variables of CMA-ES. The optimization targets include the weights β, w* and all components of the bias b. The fitness function for CMA-ES is determined by the Eq. (6).

Step 3 Start the optimization process of CMA-ES. Upon completion of the iterations, the obtained optimal solution will be adopted as the network parameter for the PINN model.

The model was trained on a Lenovo laptop equipped with an i5-12400H CPU, 16 GB RAM, and an RTX 3050 GPU with 4 GB of memory.

Model-evaluation index

This study uses RF, SVM, and BPNN as comparison models. We employ Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to fine-tune the SVM’s hyperparameters. In addition, BPNN and PINN are designed with the same network structure for comparison. These measures ensure optimal performance for each model and guarantee fairness in comparison and analysis. Lastly, we utilize the subsequent two statistical measures to evaluate the predictive effectiveness of the models.

(1) The closer the value of the decisive coefficient (R2) is to 1, the higher the fitting degree of the model to the data.

where N indicates the sample size; t(i) and o(i) correspond to the observed and expected values of the i-th test sample, respectively; \(\overline{t}\) represents the average value across all test samples.

(2) The Root Means Square Error (RMSE) indicates the model’s absolute fitting capability concerning the data. Additionally, R2 serves as a measure of the relative proportion of variance explained by the model. The RMSE has the same unit as the dependent variable, which gives it specific advantages. It is defined as follows:

Model construction

Evolution process of coal and gas outburst

Coal and gas outbursts occur as a dynamic event resulting from the interplay of subterranean stress, gas in coal seams, and the physical characteristics of coal and rock, among other variables12. The complexity of geological structures and the mining depth are primary factors influencing in-situ stress conditions. Factors associated with coal seam gas include gas pressure, the amount of gas present, and its release rate. Moreover, the physical properties of coal and rock include the firmness coefficient, seam permeability, and the initial speed of gas escape. The process of a coal and gas outburst unfolds in four stages: evolution, formation, development, and termination, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Variable selection and data set construction

(1) Analysis of key controlling factors.

Considering the accessibility and easy quantification of the influence index data, combined with the relevant research results, the ground stress Po (MPa), coal firmness coefficient f, mining depth H (m), gas pressure Pg (MPa), gas content Gc (m3/t), and initial velocity of gas emission V (m/s) are the main controlling factors affecting coal and gas outburst.

(2) Data collection.

In order to accurately describe the relationship between coal and gas outburst intensity and its main influencing factors, coal mine data was collected from a coal mine of China. These data were used to establish a predictive model based on the PINN framework. A total of 392 sets of working condition data were collected. Each data sample includes six key input parameters: ground stress (Po, MPa), coal firmness coefficient (f), mining depth (H, m), gas pressure (Pg, MPa), gas content (Gc, m3/t), and initial gas emission velocity (V, m/s). The corresponding coal and gas outburst intensity serves as the output parameter. This setup allows for studying the variation of gas outburst intensity under the influence of various factors24. Table 1 presents some of the data of the study. To ensure a balanced evaluation of the model’s performance, the dataset was randomly divided into two equal parts: 196 samples (50%) were used for training, and the remaining 196 samples (50%) were used for testing. This allocation aims to minimize sampling bias and provide a reliable assessment of the model’s generalization ability. Due to confidentiality agreements with the data-providing entity, specific details about the coal mine cannot be disclosed.

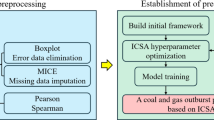

(3) Data preprocessing.

The original dataset comes from a real mining environment, containing multiple variables influenced by measurement techniques and geological variations. To ensure the robustness of the model, the raw coal mine data underwent a strict preprocessing procedure, including handling missing values, detecting anomalies, data resampling, and feature normalization25,26,27,28.

In actual mining operations, missing values often occur due to sensor failures, incomplete records, or measurement errors. To minimize the potential impact of missing values on the analysis, we applied different imputation methods based on the proportion of missing values. We imputed the missing values using the mean or median for features with a missing rate of less than 5%. When the disappeared rate ranged from 5 to 20%, we applied the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) imputation method to estimate missing values based on the similarity between data points. For features with a missing rate exceeding 20%, we removed these records to avoid introducing bias into the model. This approach ensures that the dataset retains its integrity while still representing actual mining conditions.

We employed the interquartile range (IQR) method to detect outliers, defining extreme values as those lying beyond 1.5 times the IQR from the first or third quartile. Once identified, each anomaly was examined based on its origin. If an anomaly resulted from a measurement error, it was removed from the dataset. In contrast, if the value was determined to be an extreme yet valid observation, it was replaced with the nearest data point within the acceptable range to mitigate its influence on model training and preserve data integrity.

Given the varying scales and physical units of input features such as ground stress, gas content, and mining depth, feature normalization was performed to ensure consistency across variables. We adopted min–max normalization, which linearly transforms each feature to the range [0, 1], thereby facilitating efficient convergence during training. The normalization formula is shown below:

where x' represents the normalized data, x is the original data, and xmin and xmax are the minimum and maximum values of the feature data, respectively.

Through these steps, we provided high-quality input data for the PINN model, ensuring it can effectively capture the complex relationships between geological factors and coal and gas outbursts. This significantly improved the model’s predictive performance.

Analysis of physical monotonicity relation

(1) Gas pressure. Stress is a key driving force for coal and gas outbursts4. As ground stress intensifies, the potential energy for an outburst also rises. Simultaneously, the coal’s structural integrity weakens while gas content and pressure rise, increasing the likelihood of coal and gas outburst incidents. Consequently, there exists a monotonically increasing relationship between ground stress and the risk of coal and gas outbursts, which means:

(2) Coal firmness coefficient. The firmness coefficient of coal showcases the seam’s physical and mechanical traits, serving as a key factor in analyzing coal and gas outbursts6. A more robust coal seam possesses more excellent resistance to coal and gas outbursts, thereby diminishing the outburst risk. Consequently, there is a decreasing monotonic correlation between the coal firmness coefficient and the risk of gas outbursts, implying that:

(3) Mining depth. As coal extraction extends deeper, rising ground stress reduces the permeability of coal seams and surrounding rock, leading to significant gas accumulation9. Simultaneously, deeper mining elevates the intensity of potential outbursts. Thus, a direct monotonic relationship exists between mining depth and outburst risk, meaning:

(4) Gas factor. As a primary component of outbursts, gas pressure contributes significantly to the force driving these events7,12. Increased gas pressure corresponds to a heightened risk of outbursts. The gas content within the coal seam is a significant determinant of outbursts. Reaching a critical gas content could trigger an outburst. Higher gas content is associated with more intense outbursts. The initial speed of gas release indicates coal’s permeability and gas flow characteristics. A swifter initial gas emission signifies a higher outburst risk. Thus, the relationship between gas pressure, content, and emission velocity with outburst risk is increasingly monotonic, indicating:

Based on this analysis, the study integrates the relationships among in-situ stress, coal firmness, mining depth, gas pressure, and emission characteristics with outburst risk into a PINN model to enable accurate outburst risk predictions. Figure 2 illustrates the prediction model for coal and gas outburst risk.

Discussion and analysis

Model performance analysis

To assess the efficacy of the proposed approach, this study contrasts the predictive performance of three conventional machine learning models—RF25, SVM26, and BPNN27—against the PINN model using identical training and testing datasets.

The training dataset is used to train the model and help it understand and learn to construct potential linear relationships between input variables and output variables. The test dataset is not involved in the model’s training process as an unknown data set. Still, it is a scalability test to test the model’s performance in the location condition. The training is mainly carried out on a Windows 11 computer with a CPU of R7-5800H and 16G of RAM.

Figure 3 presents the prediction outcomes for both the training and testing samples across all four models. The diagram clearly indicates that the PINN model achieves the most accurate fit, outperforming the other three models. From the perspective of evaluation indicators, the R2 values of the SVM, RF, BPNN, and PINN models on the test set are 0.883, 0.925, 0.947, and 0.966, respectively; the RMSE values of each model are 9.728, 6.452, 6.751, and 5.289, respectively. In addition, the MAE values are 8.041, 5.303, 5.624, and 4.121, while the MAPE values are 12.3%, 8.7%, 9.2%, and 6.1%, respectively. The PINN model achieves an R2 value nearly equal to 1 and has the lowest RMSE, MAE, and MAPE, signifying the best fit and demonstrating a 13% performance improvement over the SVM model in terms of R2. Analyzing the models using a 15% deviation threshold, the PINN model’s predictions consistently fall within this range. This indicates that the PINN surpasses the accuracy of the other three models and exhibits superior generalization and robustness. This superior performance can be attributed to the incorporation of physical constraints into the loss function, which effectively enhances the model’s generalization ability and reduces overfitting.

Additionally, the PINN model excels in forecasting the outburst intensity, delivering the most reliable results. It also shows that it is feasible to select six factors, like ground stress Po (MPa), coal firmness coefficient f, mining depth H (m), gas pressure Pg (MPa), gas content Gc (m3/t), initial velocity of gas emission V (m/s), as the input of the model to predict the outburst intensity.

Interpretability analysis

In this paper, the interpretability of the four models is analyzed by comparing the physical monotonicity between ground stress Po (MPa), coal firmness coefficient f, mining depth H (m), gas pressure Pg (MPa), gas content Gc (m3/t), initial velocity of gas emission V (m/s) and the gas outburst intensity, to evaluate the consistency between the model and the actual process.

Figure 4 presents the influence of gas content on outburst intensity as it increases, considering variables such as ground stress, coal firmness coefficient, mining depth, gas pressure, and initial velocity of gas emission across four different models. The results demonstrate that a significant limitation of traditional machine learning models (such as RF, SVM, and BPNN) is their "black-box" nature. While these models can learn complex patterns, they often fail to provide reasoning that aligns with physical laws. As shown in Fig. 4a and b, the RF and SVM models do not exhibit a consistent monotonic trend between gas pressure and outburst intensity. This contradicts established geological principles, which suggest that higher gas pressure typically leads to more severe outbursts due to the increased energy stored within the coal seam29. Similarly, as shown in Fig. 4c, while BPNN captures some relationships, it still demonstrates oscillatory behavior, indicating a lack of robust physical constraints in its learning process.

In contrast, the PINN model (see Fig. 4d) shows predictions that are highly consistent with physical expectations. As gas content increases, the outburst intensity steadily rises, a trend explained by the monotonicity constraints we introduced during training, which ensure the model adheres to known physical principles. Additionally, the PINN model successfully captures the interactions between multiple influencing factors. For example, as ground stress increases and coal seam hardness decreases, the model predicts a more severe outburst intensity, which aligns with real-world geological observations. By integrating these physical constraints, the PINN model overcomes the limitations of purely data-driven approaches, offering a more interpretable and reliable framework for coal and gas outburst prediction. This improvement not only enhances prediction accuracy but also boosts the model’s credibility in safety–critical mining applications.

Limitations of the PINN approach and future prospects

Traditional empirical models typically rely on predefined thresholds for parameters such as gas pressure, mining depth, and coal hardness to assess the risk of coal and gas outbursts. These models are computationally efficient, highly interpretable, and well-suited for specific scenarios. However, due to their dependence on limited historical data, they often struggle with generalization when applied to new mining areas with scarce data or significantly different geological conditions.

In contrast, PINN integrates physical constraints into neural networks, enabling stable predictive performance even with limited training data, thereby reducing reliance on large-scale historical datasets. This unique advantage makes PINN particularly valuable in data-scarce or geologically complex mining environments. Despite its strengths, PINN has certain limitations. The incorporation of physics-based constraints increases its computational cost compared to traditional machine learning models. Moreover, the model’s performance is highly sensitive to the choice of loss function weight coefficients (λ₁ and λ₂). Improper tuning of these parameters may lead to performance degradation or even divergence during training.

Additionally, the current PINN model does not yet incorporate rock degradation mechanisms induced by high-temperature, chemical, or impact conditions—factors increasingly relevant in deep mining and geothermal settings. Recent studies have shown that such environments significantly compromise rock integrity. Zhang et al.30 demonstrated that under thermo-acid coupling, elevated temperatures become the dominant driver of mass loss and porosity increase, accelerating microcrack development. Lin et al.31 proposed a multi-factor degradation model incorporating thermal stress and mineral phase transitions, revealing that temperatures above 600 °C primarily cause mechanical deterioration through mineral decomposition and crack propagation. Hong et al.32 identified 500–600 °C as a critical threshold beyond which high-temperature and water-cooling cycles markedly reduce sandstone’s impact resistance and deformation capacity. These findings underscore the importance of integrating thermo-hydro-mechanical-chemical (THMC) processes into future PINN frameworks to more accurately model rock instability under extreme conditions.

In general, PINN offers a highly interpretable, reliable, and practical approach for coal and gas outburst prediction, enhancing accuracy and reinforcing the credibility of AI-driven mining safety decisions. In mine management, PINN predictions can aid in optimizing safety strategies, such as adjusting ventilation, refining drilling sequences, or implementing additional reinforcement measures in high-risk areas to mitigate outburst hazards. Future research could further explore PINN’s application in multi-physics coupling scenarios, such as integrating seepage mechanics and rock mechanics equations to more accurately simulate the dynamic evolution of coal and gas outbursts. This would improve the model’s adaptability and reliability, advancing intelligent and efficient mining safety management.

From a practical standpoint, to adjust the PINN model parameters in real coal mine applications, practitioners are advised to calibrate the loss function weights (λ₁ and λ₂) based on geological similarity indices or expert knowledge of physical constraints. In data-rich conditions, a lower λ₂ may emphasize data fidelity, while in data-scarce regions with strong physical prior knowledge, a higher λ₂ can ensure physical consistency. Additionally, adaptive optimization strategies such as dynamic weight adjustment or Bayesian optimization can be employed to automate tuning for site-specific deployments. Field engineers can iteratively update the model by integrating real-time monitoring data to refine predictions under evolving mining conditions.

Conclusion

This study proposes a novel coal and gas outburst prediction framework by integrating physical monotonicity constraints into a neural network (PINN). By analyzing six key factors (ground stress, coal firmness coefficient, mining depth, gas pressure, gas content, and coal firmness coefficient), the model achieves an R2 of 0.966 and an RMSE of 6.452, outperforming traditional machine learning methods (RF, SVM, BPNN). Beyond improving predictive accuracy, the PINN framework offers interpretable insights into underlying physical mechanisms, addressing conventional models’ "black-box" limitations.

Future research could incorporate more complex physical constraints like seepage and rock mechanics to develop a multi-physics coupled PINN model. This would enable more precise characterization of the dynamic evolution of coal and gas outbursts, enhance the model’s adaptability and reliability across diverse geological conditions, and ultimately advance the safety and efficiency of deep mining operations.

Data availability

The complete set of data generated or analyzed in this study is contained within this published article.

References

Xue, S. et al. A review on coal and gas outburst prediction based on machine learning. J. China Coal Soc. 49(2), 664–694 (2024).

Liang, Y. P. et al. A review on prediction and early warning methods of coal and gas outburst. J. China Coal Soc. 48(8), 2976–2994 (2023).

Shao, L. S. & Gao, Y. C. SSA-SVM prediction model of coal and gas outburst based on MCMC filling. J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 19(8), 94–99 (2023).

Xu, Y. S. & Cheng, Y. W. Prediction and forecast of the SKPCA with NEAT coal and gas outburst risks. J. Saf. Environ. 21(4), 1427–1433 (2021).

Zhou, Y. et al. Prediction of coal and gas outburst based on SSA-KELM. J. Mine Autom. 49(S2), 81–86 (2023).

Wen, T. X. & Su, H. B. WOA-ELM prediction model of coal and gas outburst based on multiple imputation by chained equations. J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 18(7), 68–74 (2022).

Guo, J. D. Prediction model of coal and gas outburst based on quantum genetic fuzzy inference system. J. North China Instit. Sci. Technol. 20(6), 30–37 (2023).

Fu, H. et al. Study on coupling algorithm based on model for coal and gas outburst prediction. China Saf. Sci. J. 28(3), 84–89 (2018).

Yang, C. et al. A new method for predicting coal and gas outburst based on IAEFA-LSSVM. Mechan. Elect. Eng. Technol. 52(2), 51–54 (2023).

Wang, W. et al. Coal and gas outburst prediction model based on extension theory and its application. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 154, 329–337 (2021).

Wang, Z. E., Xu, J. M. & Cai, Z. W. A novel combined intelligent algorithm prediction model for the risk of the coal and gas outburst. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 15988 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. Early warning method for coal and gas outburst prediction based on indexes of deep learning model and statistical model. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 811978 (2022).

Ru, Y. D. et al. Real-time prediction model of coal and gas outburst. Math. Probl. Eng. 1, 2432806 (2020).

Nie, Y., Wang, Y. L. & Wang, R. Y. Coal and gas outburst risk prediction based on the F-SPA model. Energy Sour. Part A Recov. Utilization Environ. Effects 45(1), 2717–2739 (2023).

Ihssan, S. et al. Enhancing PEHD pipes reliability prediction: Integrating ANN and FEM for tensile strength analysis. Appl. Surface Sci. Adv. 23, 100630 (2024).

Shaik, N. B., Pedapati, S. R. Othman, A. R. et al. A case study to predict structural health of a gasoline pipeline using ANN and GPR approaches. In: ICPER 2020: Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Production, Energy, and Reliability. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 611–624 (2022).

Maiti, M. et al. Recent advances and applications of fractional-order neural networks. Eng. J. 26(7), 49–67 (2022).

Deressa, G. W. & Choudhary, B. S. Evaluating productivity in opencast mines: A machine learning analysis of drill-blast and surface miner operations. Nat. Resour. Res. 34(1), 215–251 (2025).

Lawal, A. I. et al. Prediction of mechanical properties of coal from non-destructive properties: A comparative application of MARS, ANN, and GA[J]. Nat. Resour. Res. 30, 4547–4563 (2021).

Onifade, M. et al. Development of multiple soft computing models for estimating organic and inorganic constituents in coal. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 31(3), 483–494 (2021).

Lawal, A. I. et al. On the performance assessment of ANN and spotted hyena optimized ANN to predict the spontaneous combustion liability of coal. Combust. Sci. Technol. 194(7), 1408–1432 (2022).

Ren, S. J. et al. Forecasting method for NOx emission in coal fired boiler based on physics-informed neural network. Proc. CSEE 44(20), 8157–8165 (2024).

Wang, J. X., Wu, J. L. & Xiao, H. Physics-informed machine learning approach for reconstructing Reynolds stress modeling discrepancies based on DNS data. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2(3), 034603 (2017).

Li, S. & Hu, H. Y. Risk identification of coal and gas outburst based on KPCA and improved extreme learning machine model. Appl. Res. Comput. 35(1), 172–176 (2018).

Qiao, W. H. et al. Gas prominence prediction based on GRA-BSMOTE-RF under unbalanced samples. Coal Technol. 43(2), 121–125 (2024).

Wan, Y. et al. Prediction of coal and gas outburst based on over-sampling support vector machine. Sci. Technol. Eng. 21(28), 12080–12087 (2021).

Ma, L., Lu, W. D. & Wei, G. Y. Study on prediction method of coal seam gas content based on GASA-BP neural network. J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 18(8), 59–65 (2022).

Zhao, S. et al. Interpretable machine learning for predicting and evaluating hydrogen supercritical water gasification production of biomass. J. Clean. Prod. 316, 128244 (2021).

Zhou, B. et al. Effects of gas pressure on the dynamic response of two-phase flow for coal-gas outburst. Powder Technol. 377, 55–69 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Experimental study on the deterioration mechanisms of physical and mechanical properties of red sandstone after thermal-acid coupling treatment. Constr. Build. Mater. 455, 139106 (2024).

Lin, H. et al. Study on the degradation mechanism of mechanical properties of red sandstone under static and dynamic loading after different high temperatures. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 11611 (2025).

Hong, L. et al. Kinetic characterisation of sandstone exposed to high temperature-water cooling cycle treatments under impact loading: From the perspective of geohazard. Geohazard Mechan. 12, 1 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this research was provided by the S&T Innovation and Development Project from the Information Institution of the Ministry of Emergency Management (Project No. 2024507).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data analysis was carried out by Lei Wang, who also prepared the manuscript. The research concept was developed by Baoshan Jia and Guorui Su.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Jia, B. & Su, G. Prediction of coal and gas outbursts based on physics informed neural networks and traditional machine learning models. Sci Rep 15, 29984 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02320-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02320-4