Abstract

Patients with ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma (OHGSC) gradually acquire resistance to standard chemotherapy following recurrence. In our previous study on OHGSC, histone deacetylase (HDAC) 6 upregulation led to a poor prognosis, and programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) expression was positively correlated with HDAC6 expression. We analyzed HDAC6 and PD-L1 expression before and after chemotherapy to investigate their association with chemotherapy resistance and patient survival. PD-L1 and HDAC6 expression were immunohistochemically analyzed using clinical samples from 54 patients with OHGSC before and after standard chemotherapy. High PD-L1 expression (≥ 5%) was detected in five and nine patients before and after chemotherapy, respectively. The mean PD-L1-positive rate after chemotherapy was 3.88%, which was significantly higher than the rate before chemotherapy (0.68%). The high HDAC6 expression frequency significantly increased from four patients before chemotherapy to 13 patients after. High PD-L1 expression after chemotherapy was significantly correlated with a chemotherapy response score of three, signifying a good chemo-response. High PD-L1 expression after chemotherapy was associated with poor progression-free survival and overall survival in patients who underwent complete surgical resection. In OHGSC, residual tumors after chemotherapy show enhanced HDAC6 and PD-L1 expression. Upregulated PD-L1 after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) has contradictory characteristics, indicating a good response to chemotherapy but unfavorable survival. It is a wolf in sheep’s clothing, and physicians should not make an optimistic prognosis even if the patient shows a good response to NAC. HDAC6 and PD-L1 may be therapeutic targets and prognostic factors for residual tumors after chemotherapy in OHGSC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma (OHGSC) is the most frequent histological subtype of ovarian cancer and the leading cause of death due to cancer of the female genital tract1. Typically, patients with OHGSC respond well to platinum-based chemotherapy, which is a standard regimen for OHGSC. However, OHGSCs frequently recur and gradually acquire resistance to standard chemotherapy regimens2. Recently, poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors have improved the clinical outcomes of patients with ovarian cancer featuring BRCA mutations or homologous recombination deficiency3. Nonetheless, more effective treatment strategies for advanced OHGSC are required. Immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting programmed death-1 (PD-1)/programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 have caused breakthroughs in treatment strategies for various cancers4. In our previous study on ovarian cancer, PD-L1 expression was positively correlated with histone deacetylase (HDAC) 6 expression, and HDAC6 upregulation led to a poor prognosis5,6,7. HDAC6 increases deacetylated α-tubulin levels, which upregulate cancer cell growth by enhancing microtubule dynamics8,9. HDAC6 upregulation also promotes platinum resistance, and HDAC6 downregulation enhances platinum agent-induced DNA damage and apoptosis10. HDAC6 is also an immunomodulator, and the co-suppression of HDAC6 and PD-L1 has a synergistic anti-tumor effect for ovarian cancer11. Notably, Beltrame et al.12 and Takaya et al.13 have shown that the molecular profiles of OHGSC are significantly different before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC). However, the evidence for HDAC6 and PD-L1 expression after NAC is not sufficient. In this study, we compared the expression of HDAC6 and PD-L1 by immunohistochemistry before and after chemotherapy to verify whether their expression affects chemotherapy resistance and patient prognosis in OHGSC.

Methods

Patients and samples

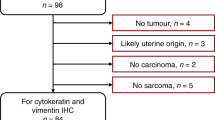

We identified 57 patients with OHGSC who were histologically diagnosed and had received NAC between 2007 and 2015 at Saitama Medical University International Medical Center. Clinicopathological, treatment, and follow-up data were also collected. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) (IRB number: 16–257) of Saitama Medical University International Medical Center. Written informed consent (or a formal waiver of consent) was obtained from all patients. Tumor samples were acquired before and after chemotherapy in all patients. Based on the results of an omental examination, chemotherapy response score (CRS) was used to classify patients as follows: patients with CRS3 had a complete/near-complete response, those with CRS2 had a partial response, and those with CRS1 had no response or a minimal response14,15. The surgical status was classified as complete resection (R0) or incomplete resection (R1). We also evaluate Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) and cancer antigen 125 ELIMination rate constant K (KELIM) score16.

Immunohistochemical staining and assessments

Immunohistochemical expressions of PD-L1 and HDAC6 were analyzed using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor samples from both before and after chemotherapy. A Dako Autostainer Link 48 (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The Target Retrieval Solution was applied for antigen retrieval at 98 °C for 20 min. Sections were incubated with primary antibodies (monoclonal rabbit anti-PD-L1, 1:100, 28 − 8 pharmDx, Dako North America, CA, USA; polyclonal rabbit anti-HDAC6, 1:500, ab1440, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) at 25 °C for 60 min, followed by incubation with a secondary antibody (EnVision FLEX/HRP, Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) at 25 °C for 30 min. The chromogenic reaction was performed using diaminobenzidine and hydrogen peroxide. Immunohistochemical expression was scored by two researchers (MiY and MaY) who were blinded to the clinicopathological characteristics (Fig. 1).

PD-L1 positivity was defined as staining in ≥ 5% of carcinoma cells17. PD-L1 expression was also analyzed in a semiquantitative manner by scoring the proportion of stained carcinoma cells over the total number of carcinoma cells, ranging from 5 to 100% in 5% increments. We also caluculated the mean of PD-L1 expression before and after NAC using sum of all PD-L1 percentages divided by the case numbers. High expression of HDAC6 was defined as staining in ≥ 50% of carcinoma cells6,7.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Fisher’s exact test or Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to analyze the correlation between immunohistochemical expressions and clinicopathological characteristics. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate survival curves, and the log-rank test was used to test differences between groups. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to perform multivariate survival analysis. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics and immunohistochemical expression after NAC

The baseline clinicopathological characteristics of the 57 patients with OHGSC who underwent platinum-based systemic chemotherapy as a neoadjuvant treatment are summarized in Table 1. The median follow-up period was 43.5 months (range 8–105 months).

Most patients (55 [96.5%]) underwent interval debulking surgery, but two (3.5%) patients only underwent a biopsy because of unresectable lesions. Of the 54 patients for whom omental CRS was able to be evaluated, 29 (53.7%) were classified as CRS3 (sensitive to chemotherapy), whereas 25 (46.4%) were classified as CRS1–2 (resistant or intermediate to chemotherapy). None of the patients received maintenance therapy with PARP inhibitors.

Change in PD-L1 and HDAC6 expression following NAC

Table 2 shows PD-L1 and HDAC6 expression in the 57 patients with paired pre- and post-NAC tumor samples. Before NAC, four patients showed high HDAC6 expression, and five patients showed positive PD-L1 expression. No significant correlations were shown between HDAC6 and PD-L1 expression after NAC.

After NAC, high HDAC6 expression was observed in several patients (13, P = 0.019). The mean PD-L1-positive rate after NAC was 3.88%, which was significantly higher than the rate before NAC (0.68%) (P = 0.045). The association between patient characteristics and immunohistochemical HDAC6 and PD-L1 expression after NAC are summarized in Table 3.

PD-L1-positive expression after NAC was significantly correlated with CRS3 (P = 0.042), which suggests a favorable response to chemotherapy.

Correlation between PD-L1 expression after NAC and clinical outcomes

Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed that positive PD-L1 expression and high HDAC6 expression after NAC were not significantly associated with progression-free survival (PFS) (P = 0.238 and P = 0.108, respectively) or overall survival (OS) (P = 0.493 and P = 0.377, respectively). Following multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model, surgical status was an independent prognostic factor for PFS (hazard ratio = 1.92; 95% confidence interval, 1.07–3.42; P = 0.028). No independent prognostic factors for OS were identified in the multivariate analysis.

We also performed a subgroup analysis based on the surgical status. Patients with R0 and PD-L1 positivity after NAC had poorer PFS (Fig. 2A) and poorer OS (Fig. 2B) than patients with R0 and PD-L1 negativity after NAC (P = 0.037 and P = 0.039, respectively).

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (A PFS; B OS). Asterisks indicate the p-values for comparing R0 with PD-L1 negative to R0 with PD-L1 positive, and daggers indicate the p-values for R0 with PD-L1 positive to R1. P-values were calculated using the log-rank test. PFS progression-free survival, OS overall survival, PD-L1 programmed death ligand-1.

However, no significant differences were observed in PFS or OS between patients with R0 and PD-L1 positivity after NAC and those with R1 (P = 0.971 and P = 0.705, respectively; Fig. 2A,B). HDAC6 expression after NAC was not significantly associated with PFS or OS in the subgroup analysis based on surgical status.

Discussion

The present study showed that immunohistochemical expression of HDAC6 and PD-L1 were upregulated in residual tumors after the initial platinum-based standard chemotherapy in OHGSC. Table 4 shows a review of studies regarding PD-L1 expression after NAC along with the prognosis for OHGSC17,18,19,20,21.

The first novelty of the present study is to report that high PD-L1 expression after NAC is significantly associated with poor PFS and OS in patients who undergo complete surgical resection. Upregulation of PD-L1 expression after NAC has been previously reported, but it has not been shown to contribute to the prognosis prediction. Guo et al. reported that elevated PD-L1 expression in residual tumors after platinum-based NAC was associated with a reduced chemotherapy response and inferior PFS in patients with lung cancer22. The mechanism underlying the role of chemotherapy in the variation in PD-L1 expression has not been fully elucidated. Peng et al. suggested that chemotherapy (platinum or taxane agents) could upregulate PD-L1 expression through nuclear factor kappa B to induce local immunosuppression in ovarian cancer23. Chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression may be a target for immunotherapy via PD1/PD-L1. A combination of chemotherapy (platinum and taxane agents) and pembrolizumab improved PFS and OS among patients with persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer24. However, in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, nivolumab did not improve OS and PFS compared to gemcitabine or pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in a phase III study25. New therapeutic strategies are required to maximize the effects of immunotherapy targeting PD-1/PD-L1 in ovarian cancer. Notably, high expression of PD-L1 after NAC exhibits contradictory characteristics with good response to initial chemotherapy but unfavorable survival outcomes. Therefore, upregulated PD-L1 after NAC is a wolf in sheep’s clothing, and the physician should not make an optimistic prognosis even if the patient shows a good response to NAC.

The second novelty of the present study is to demonstrate that HDAC6 expression after NAC is upregulated compared to before NAC in OHGSC5. HDAC6 acts as an immunomodulator via PD-1/PD-L1, and co-suppression of HDAC6 and PD-L1 has a synergistic anti-tumor effect on ovarian cancer11. A phase Ib study of an HDAC6 inhibitor and nivolumab combination therapy for lung cancer has already been completed26. HDAC6 upregulation leads to resistance to platinum agents, whereas HDAC6 downregulation enhances platinum agent-induced DNA damage and apoptosis10. HDAC6 upregulation induces taxane resistance, and HDAC6 blockage reverses resistance to taxane agents via the acetylation of α-tubulin in ovarian cancer27,28. HDAC6 inhibitors exhibit an anti-tumor effect in vitro29,30,31,32, are well tolerated, and show minimal toxicity in phase Ib trials31. HDAC6 reduces kidney failure33 and peripheral neuropathy34, which are common adverse effects of platinum and taxane agents. Therefore, HDAC6 upregulation in residual tumors after NAC for OHGSC is considered a step in acquiring chemoresistance. HDAC6 suppression may lead to improved chemoresistance and synergistic effects with immunotherapy targeting PD-1/PD-L1.

This study has some limitations worth considering. First, the number of patients in the study may not have been sufficiently large. In particular, several subgroups, including the PD-L1-positive group, had only single-digit cases. The statistical legitimacy is debatable because of limited case numbers and multiple analyses. However, as Table 3 shows, this study is the third largest to date and can be interpreted as having a relatively large sample size for these types of studies. Second, the tumor immune environment, such as tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and cluster of differentiation 8 immunohistochemistry, has not been investigated. However, this is a unique study that focuses on chemotherapy-induced changes in HDAC6 and PD-L1 expression. Finally, no molecular analysis was performed on the pre- and post-NAC specimens. We tried to analyze HDAC6 gene expression using published data, but we could not obtain the evidence of HDAC6 gene upregulations between pre- and post-NAC in OHGSC35,36,37. The molecular analysis will be the subject of future studies.

In conclusion, residual tumors of OHGSC after NAC show enhanced expression of HDAC6 and PD-L1, which are associated with tumor immunity, cell proliferation, and chemoresistance. PD-L1 expression also correlates with patient prognosis. These results suggest that HDAC6 and PD-L1 may be therapeutic targets and prognostic factors for residual tumors after standard chemotherapy in OHGSC.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- OHGSC:

-

Ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma

- PARP:

-

Poly ADP-ribose polymerase

- PD-1:

-

Programmed death-1

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed death ligand-1

- HDAC:

-

Histone deacetylase

- NAC:

-

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

- IRB:

-

Institutional review board

- CRS:

-

Chemotherapy response score

- R0:

-

Complete resection

- R1:

-

Incomplete resection

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

- OS:

-

Overall survival

References

Heintz, A. P. et al. Carcinoma of the ovary. FIGO 26th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 95 (Suppl 1): S161-192. (2006).

Bookman, M. A. First-line chemotherapy in epithelial ovarian cancer. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 55 (1), 96–113 (2012).

Ray-Coquard, I. et al. Olaparib plus bevacizumab as First-Line maintenance in ovarian Cancer. N Engl. J. Med. 381 (25), 2416–2428 (2019).

Marabelle, A. et al. Efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with noncolorectal high microsatellite instability/mismatch Repair-Deficient cancer: results from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 38 (1), 1–10 (2020).

Yano, M. et al. Association of histone deacetylase expression with histology and prognosis of ovarian cancer. Oncol. Lett. 15 (3), 3524–3531 (2018).

Yano, M. et al. Clinicopathological correlation of ARID1A status with HDAC6 and its related factors in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 2397 (2019).

Yano, M. et al. Up-regulation of HDAC6 results in poor prognosis and chemoresistance in patients with advanced ovarian High-grade serous carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 41 (3), 1647–1654 (2021).

Miyake, Y. et al. Structural insights into HDAC6 tubulin deacetylation and its selective Inhibition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12 (9), 748–754 (2016).

Hubbert, C. et al. HDAC6 is a microtubule-associated deacetylase. Nature 417 (6887), 455–458 (2002).

Wang, L. et al. Depletion of HDAC6 enhances cisplatin-induced DNA damage and apoptosis in non-small cell lung cancer cells. PLoS One. 7 (9), e44265 (2012).

Fukumoto, T. et al. HDAC6 Inhibition synergizes with Anti-PD-L1 therapy in ARID1A-Inactivated ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. 79 (21), 5482–5489 (2019).

Beltrame, L. et al. Profiling cancer gene mutations in longitudinal epithelial ovarian cancer biopsies by targeted next-generation sequencing: a retrospective study. Ann. Oncol. 26 (7), 1363–1371 (2015).

Takaya, H. et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and homologous recombination deficiency of high-grade serous ovarian cancer are associated with prognosis and molecular subtype and change in treatment course. Gynecol. Oncol. 156 (2), 415–422 (2020).

Bohm, S. et al. Chemotherapy response score: development and validation of a system to quantify histopathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in Tubo-Ovarian High-Grade serous carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 33 (22), 2457–2463 (2015).

Cohen, P. A. et al. Pathological chemotherapy response score is prognostic in tubo-ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. Gynecol. Oncol. (2019).

Piedimonte, S. et al. Correlating the KELIM (CA125 elimination rate constant K) score and the chemo-response score as predictors of chemosensitivity in patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 187, 92–97 (2024).

Mesnage, S. J. L. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) increases immune infiltration and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC). Ann. Oncol. 28 (3), 651–657 (2017).

Lee, Y. J. et al. Dynamics of the tumor immune microenvironment during neoadjuvant chemotherapy of High-Grade serous ovarian cancer. cancer. (Basel). 14 (9) (2022).

Kim, H. S. et al. Expression of programmed cell death ligand 1 and immune checkpoint markers in residual tumors after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for advanced high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 151 (3), 414–421 (2018).

Lo, C. S. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy of ovarian Cancer results in three patterns of Tumor-Infiltrating lymphocyte response with distinct implications for immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 23 (4), 925–934 (2017).

Böhm, S. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy modulates the immune microenvironment in metastases of Tubo-Ovarian High-Grade serous carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 22 (12), 3025–3036 (2016).

Guo, L. et al. Variation of programmed death ligand 1 expression after Platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy in lung Cancer. J. Immunother. 42 (6), 215–220 (2019).

Peng, J. et al. Chemotherapy induces programmed cell Death-Ligand 1 overexpression via the nuclear Factor-κB to foster an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. 75 (23), 5034–5045 (2015).

Colombo, N. et al. Pembrolizumab for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical Cancer. N Engl. J. Med. 385 (20), 1856–1867 (2021).

Hamanishi, J. et al. Nivolumab versus gemcitabine or pegylated liposomal doxorubicin for patients with Platinum-Resistant ovarian cancer: Open-Label, randomized trial in Japan (NINJA). J. Clin. Oncol. 39 (33), 3671–3681 (2021).

Awad, M. M. et al. Selective histone deacetylase inhibitor ACY-241 (Citarinostat) plus nivolumab in advanced Non-Small cell lung cancer: results from a phase Ib study. Front. Oncol. 11, 696512 (2021).

Angelucci, A. et al. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid partly reverses resistance to Paclitaxel in human ovarian cancer cell lines. Gynecol. Oncol. 119 (3), 557–563 (2010).

Marcus, A. I. et al. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors reverse taxane resistance. Cancer Res. 66 (17), 8838–8846 (2006).

Azuma, K. et al. Association of Estrogen receptor alpha and histone deacetylase 6 causes rapid deacetylation of tubulin in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 69 (7), 2935–2940 (2009).

Dong, J. et al. A novel HDAC6 inhibitor exerts an anti-cancer effect by triggering cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in gastric cancer. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 828, 67–79 (2018).

Yee, A. J. et al. Ricolinostat plus Lenalidomide, and dexamethasone in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: a multicentre phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 17 (11), 1569–1578 (2016).

Amengual, J. E. et al. Dual targeting of protein degradation pathways with the selective HDAC6 inhibitor ACY-1215 and bortezomib is synergistic in lymphoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 21 (20), 4663–4675 (2015).

Tang, J. et al. Blockade of histone deacetylase 6 protects against cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Clin. Sci. (Lond). 132 (3), 339–359 (2018).

Krukowski, K. et al. HDAC6 Inhibition effectively reverses chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Pain 158 (6), 1126–1137 (2017).

Javellana, M. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy induces genomic and transcriptomic changes in ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. 82 (1), 169–176 (2022).

Zhang, K. et al. Longitudinal single-cell RNA-seq analysis reveals stress-promoted chemoresistance in metastatic ovarian cancer. Sci. Adv. 8 (8), eabm1831 (2022).

Koussounadis, A., Langdon, S. P., Harrison, D. J. & Smith, V. A. Chemotherapy-induced dynamic gene expression changes in vivo are prognostic in ovarian cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 110 (12), 2975–2984 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank Editage (http://www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding

This study was funded by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture of Japan (Research Project Numbers: 22K15409) and Kanzawa Medical Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mi.Y.: Conception, Design, Acquisition, Analysis, and Interpretation of Data and Drafting of the Manuscript. Ma.Y.: Conception, Design, and Critical Revision of the Manuscript for the Inclusion of Important Intellectual Content and Writing Supervision. K.H.: Data Acquisition and Supervision. A.O.: Data Acquisition. E.K.: Critical Revision of the Manuscript for Important Intellectual Content. M.M. and T.K.: Conception and Design of the Manuscript for Important Intellectual Content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Ethics Committee of the Saitama Medical University International Medical Centre, (IRB number, 16–257), and was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983. All study participants provided informed consent (or a formal waiver of consent).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yano, M., Katoh, T., Miyazawa, M. et al. Histone deacetylase 6 and programmed death ligand-1 expressions after neoadjuvant chemotherapy are upregulated in patients with ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 19231 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02329-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02329-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Fedratinib inhibits ovarian cancer progression by downregulating QPCT expression

Discover Oncology (2025)