Abstract

Over the years, toxicity prediction has been a challenging task. Artificial intelligence and machine learning provide a platform to study toxicity prediction more accurately with a reduced time span. An optimized ensembled model is used to contrast the results of seven machine learning algorithms and three deep learning models with regard to state-of-the-art parameters. In the paper, optimized model is developed that combined eager random forest and sluggish k star techniques. State-of-the-art parameters have been evaluated and compared for three scenarios. In first scenario with original features, in the second scenario using feature selection and resampling technique with the percentage split method, and in the third scenario using feature selection and resampling technique with 10-fold cross-validation. The principal component analysis is performed for feature selection. An optimized ensembled model performs well in comparison to other models in all three scenarios. It achieved an accuracy of 77% in the first scenario, 89% in the second scenario, and 93% in the third scenario. The proposed model shows the performance increase in accuracy by 8% as compared to the top performer Kstar machine learning model and 21% as compared to deep learning model AIPs-DeepEnC-GA which is remarkable. Also there is significant improvement in other important evaluation parameters in comparison to top performing models. Further concept of W-saw score and L-saw is presented for all the scenarios. An optimized ensembled model using feature selection and resampling technique with tenfold cross-validation performs best among all machine learning models in all the scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The degree to which a medicinal compound is hazardous to living things is known as its toxicity1. Toxicology prediction is extremely difficult. Worldwide, numerous medicinal compounds are created each year. Toxicity is related to the amount of chemicals that are inhaled, applied, or injected and can result in death, allergies, or negative consequences on living organisms2. A drug’s toxicity can differ from person to person as per their characteristics. Therefore, a dose that is curative for one patient may be poisonous for other3. Drugs are necessary for living beings to help with illness, disease diagnosis, or disease prevention4. A new medication or chemical molecule must go through a lengthy, expensive process of development. There are two types of chemicals, namely active and inactive ingredients found in every medicine. The term “active ingredients” refers to the substance that constitutes the therapeutic essence of medicine5. The other is known as an inactive component, which has no direct therapeutic benefit but is utilized to balance a drug’s potency. Inactive medications are occasionally used to bind, coat, flavor, or even speed up the breakdown of active pharmaceuticals. Therefore, maintaining a balance between active and inactive medications is crucial. The imbalance of active and inactive medications results in toxicity6. Thus, predicting drug toxicity is vital. Over the last few decades, toxicity has been a crucial subject of ongoing research7. In the past, drug testing was performed on animals followed by human trials but computational intelligence makes it possible to forecast and assess a drug’s toxicity8. It is possible to forecast drug toxicity using machine learning approaches9. These methods reduce the cost and duration of the evolution process. A critical phase in the machine learning pipeline is FS, where pertinent characteristics are selected in the dataset and excludes redundant attributes10. Proper feature selection can shorten training times, prevent overfitting, and enhance model performance. There are numerous ways for selecting features, ranging from straightforward to sophisticated11. The best feature subset for a particular machine learning assignment is detected by frequently considering a combination of approaches and experimenting carefully. Additionally to prevent data leakage and estimate performance of model precisely, feature selection must be carried out inside a validated framework12. A common dimensionality reduction method in statistics and machine learning is principal component analysis13. Its main applications are feature selection and data visualization, with the aim of decreasing a dataset’s dimensionality while retaining as much crucial data as feasible. Principal component Analysis uses linear combinations to produce the main components, and the term “combinations” refers to the linear combinations of the original features14. The goal of PCA is to identify a set of orthogonal (i.e., uncorrelated) linear combinations of the initial characteristics that best account for the data’s variation. The original attributes are combined with particular weights or coefficients to create these linear combinations, which are known as the principal components. In brief, PCA diminishes the amplitude of the data by keeping as much information as feasible. The process of dimension reduction is applied by combining the actual features presented as principal components15. These combinations are determined by assigning weight to original features that are necessary for structure and reducing the dimension of data. Resampling is a method to change the dataset by addition, deletion, or change of dataset points. This is used to overcome class imbalance and fitting problems in a dataset16. Oversampling and undersampling can add biases or lower the quantity of data accessible for training17. It must be done with caution. The resampling approach and parameters are persuaded by the dataset, specific challenge, and the desired result. The appropriate model selection, hyperparameter tweaking, and cross-validation must be used in association with resampling to get a balanced and robust machine-learning model18. The process of splitting a dataset into subsets for training, testing, and validation is termed as percentage split in machine learning19. These subsets are given in terms of the percentage of a dataset. The percentage split selection is based on the size of the dataset and the data accessibility. In a typical percentage split, for training, testing, and validation for instance criteria of 80%, 10%, and 10% can be utilized20. Depending upon data size we can build a robust model21. However, depending upon the need of a project, the percentage split can be adjusted to get the best machine learning model. To avoid biases, it is important to split data at random or by the use of a method that ensures the best subsets of the entire dataset. K-fold cross-validation is a well-known technique to apply22. It helps to estimate the performance on data when a dataset is small. In the technique, the dataset is split into equal size of k-folds. Noted the performance statistics or metrics23. Calculate the performance metric(s) average and standard deviation over all K iterations. In comparison to a single train-test split, these statistics offer a more reliable estimation of your model’s performance. The size of our dataset and the available computational resources are only two examples of the many variables that influence the choice of K. K frequently has values between 5 and 10, and 10-fold cross-validation is frequently a suitable place to start. We can experiment with several K values to discover which one gives the most accurate performance estimates for your model24. K-fold cross-validation offers a more thorough review than a single train-test split, which can be impacted by the randomness of the split, and aids in evaluating. A number of machines learning algorithms are applied and the performance is evaluated which is quite satisfactory but still the challenges needs to be addressed are overfitting, generalization, dependency on a single factor i.e. accuracy. The presented paper uses k-fold cross validation method to deal with overfitting. Ensembling of lazy and eager is performed to address generalization. Saw scores are composite scores of all performance parameters which strengthens the optimized model.

The main contribution of presented paper is to

-

A number of machine learning approaches are already used to improve the performance of the model.

-

Optimize and strengthen the model with multidisciplinary domain operational research where W-saw and L-saw are calculated and their respective scores validate the performance of optimized model before deployment.

Literature review

In this section, different techniques used by researchers in machine learning have been discussed with their findings of the research. Sukumaran et al. created a mongrel method based on particle swarm optimisation and support vector machines to autonomously analyse computed tomography images, offering a high likelihood of detecting the existence of Covid-19-related pneumonia25. The model was trained and clarifies the existence of disease in patients that saves time frame for physicians. Sarwar et al. exhibited an ensembled model in deaconing type II diabetes26. The authors considered a total of 15 models but used five main approaches. To achieve the desired results they employed matrix laboratory and the weka tool. The voting technique is used in ensembling the classifiers. A medical dataset of 400 people around the globe is considered during the research. Verma et al. provided an analysis of machine learning methods, both supervised and unsupervised, for identifying incredulous behaviour27. The authors studied the behavior of a single person in a crowd with artificial intelligence techniques. Bojamma et al. studied the importance of plant identification in balancing the nature and saving the geodiversity of a zone28. The authors assessed the condition to explore latest approaches for systematic identifications of flora. The combined efforts of artificial intelligence and botanists are important to robotize the complete method of recognition of plants considering leaves as crucial characteristics that help identify between different plants. Shidnal et al. studied about lack of nutrients in a paddy crop. They used neural network to categorise the shortcomings using tensor flow29. Clustering technique k means is applied to build clusters30. The authors estimated state of deficiencies on a measurable basis. A rule-based matrix is also used to estimate cropland’s yield. Table 1 represents the literature based on the algorithm used in the study.

Tables 2 and 3 present the study of evaluation parameters and approaches used in different research respectively.

Renowned researchers are applying machine learning algorithms to understand highly complex problems. There is always a need for pre-processing to better understand complex data. New techniques are needed for pre-processing methods like feature selection and clustering as well. Prominent work is done by the researchers in the field, now ensembling in the feature selection is necessary to make a robust model. Gini index, principal component analysis, recursive feature selection, fisher filtering, Lasso regression, correlation attribute evaluator, and many more feature selection methods are used by researchers. Now researchers are optimizing their prominent work toward hybrid or ensembling of algorithms.

The paper is structured as:

-

I)

Section “Proposed Methodology” depicts methodology adopted.

-

II)

Section “Results and discussions” presents detailed discussions about the dataset and results achieved in all the three scenarios described.

-

III)

Section “Conclusion” presents conclusion and future scope.

Proposed methodology

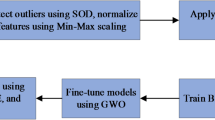

In the research, seven computer-aided machine learning models are evaluated and the performance is compared. Gaussian Process (GP), Linear Regression (LR), Sequential monitoring optimization (SMO), Kstar, Bagging, Decision Tree (DT) and Random Forest (RF) are taken into consideration to predict toxicity. Through ensemble of the Random Forest and Kstar algorithms, we were able to develop an optimized ensembled model (OEKRF). Three scenarios are introduced for the preprocessing and training of data. Seven machine learning algorithms and optimized KRF are evaluated and compared in all three scenarios. Results are compared in aspects state of art parameters. Further to strengthen the model, W-saw and L-saw scores are also evaluated, and the framework of a robust model is deployed. Figure 1 represents methodology proposed for the model.

Pseudocode is also presented below to elaborate the process in detail:

Results and discussions

This section is divided into two subsections. First subsection presents the dataset description in which different attributes of dataset are described and the second subsection depicts the result analysis with discussions.

Dataset description

The toxicity dataset that is used in an implementation is obtained from UC Irvine ML depository. There are 546 instances in the dataset, and there are eight predictive attributes. The attributes are listed in Table 4 and a detailed description is also presented.

Table 5 shows some tuples of dataset which are representative of the entire dataset.

In the paper, the principal component analysis technique is employed to procure prime combination of the features. Principal component analysis is performed in conjunction with ranker research method. Dimensionality reduction is done by choosing eigen vectors to account for some percentage of the variance in the original data. Five new combinations (NC) have been introduced for the optimized toxicity prediction model. Table 6 presents the description of new features as per the technique.

The correlation among the various combinations is shown in Table 7.

Heat map is a technique used for data visualization which represents numerical values in the dataset by using different color combinations. It depicts correlation coefficients by color gradients. In Fig. 2, red color depicts the highest value of correlation coefficient, yellow color shows the mediate values and green color shows the lowest value of correlation coefficient.

Through ensemble of the Random Forest and Kstar algorithms, we were able to create a better regression model (OEKRF). Figure 3 represents the methodology for ensembled model and Classifier − 1 and classifier- 2 are applying a lazy and eager algorithm for prediction. Further ensembling is performed using different algorithms.

Algorithm: Prediction and Ensembling

Results and discussions

Three different scenarios have been considered for the evaluation and comparison of seven machine-learning algorithms and optimized KRF as follows:

-

I)

Evaluation and comparison with original features.

-

II)

Evaluation and comparison with feature selection, resampling, and percentage split method.

-

III)

Evaluation and comparison with feature selection, resampling, and 10-fold cross-validation method.

Coefficient of correlation is denoted by R value. It represents how much one variable is correlated to another variable. The value may be positive or negative. It varies from − 1 to 1. The coefficient of determination (COD), also referred to as the R2 score, is used to evaluate how effective a regression model is. The degree of change in the output dependent characteristic can be predicted from the input independent variables. When the COD score is 1, the data were correctly predicted by the regression. It ranges from 0 to 1. MAE and RMSE is a statistical indicator used to assess the efficacy of a machine learning algorithm on a particular dataset. It contrasts the variations between actual data and predictions while outlining the model evaluation error. Q represents the accuracy of the models in percentage. State of art parameters is presented in Table 8 for a scenario I i.e. with original features. An optimized ensembled KRF is evaluated best with the R value as 0.9, COD value as 0.81, MAE value as 0.23, and RMSE value as 0.3. Accuracy is also best for an ensembled model and the observed value is 77% in scenario I.

State of art parameters is depicted in Table 9 for scenario II i.e. with feature selection, resampling, and percentage split method. Optimized ensembled KRF has performed well again in comparison to other machine learning algorithms with R value as 0.91, COD value as 0.83, MAE value as 0.11, and RMSE value as 0.28. It performed well in terms of achieving an accuracy of 89% in scenario II.

State of art parameters is compared in Table 10 for scenario III i.e. with feature selection, resampling, and 10-fold cross-validation method. The optimized ensembled model in scenario III outperforms all other models by achieving an accuracy of 93%, R value as 0.93, COD value as 0.86, MAE value as 0.07 and RMSE value as 0.25.

Figures 4 and 5 present comparison of coefficient of correlation (R) and coefficient of determination (COD) in all the three scenarios respectively. Figures 6 and 7 depict the MAE and RMSE in all the three scenarios respectively.

The optimized ensembled toxicity prediction model KRF performs well in all the scenarios in comparison to seven machine learning algorithms. When the optimized model is compared in all three scenarios, it performed best in scenario III. Accuracy comparison is shown separately in Table 11; Fig. 8 to present the performance of all models together. The highest accuracy is achieved by optimized KRF in scenario III as 93%. For scenario I and scenario II, the accuracy achieved by the optimized model is 77% and 89% respectively.

Further, the concept of W-saw and L-saw scores are introduced to strengthen the optimized toxicity prediction model. The operational research terms W-saw and L-saw are the composite score of multiple performance factors into a single score. W-saw score of the model should be high and L-saw score should be the lowest. Both scores show that the performance of the model is not dependent on the single factor. By pursue these scores leads to monitor changes to the model performance. Tables 12 and 13 represent the W-saw score and L-saw score respectively for different machine learning algorithms. W-saw and L-saw scores comparison is shown separately in Figs. 9 and 10 to present the performance of all models together. The W-saw score for an optimized model in scenario I is 0.83, for scenario II is 0.88, and is best for scenario III by achieving a 0.91 score.

The L-saw score for an optimized model in the scenario I is 0.27, in scenario II is 0.20, and is best for scenario III by achieving the lowest value of 0.16.

Recent deep learning based models have been introduced and compared with proposed OEKRF model. AIPs-DeepEnC-GA is a deep learning model which combines the strength of deep EnC and genetic algorithm to find the nonlinear relation between molecular structure and toxicity, DeepAIPs-Pred model learns the toxic patterns by monitoring the sequence activities of features and Deepstacked-AVPs model embeds the features and finds all the possible patterns to extend the model generalization for unknown data42–43. Table 14 depicts the performance of deep learning models. AIPs-DeepEnC-GA model performs better with R value as 0.82, COD value as 0.807, MAE as 0.24, RMSE as 0.30 and accuracy of 72%.

So our results evaluate that optimized ensembled KRF is best in comparison to seven machine learning algorithms and three deep learning algorithms in all aspects. Table 15 depicts the performance of optimized ensembled KRF in all the three scenarios. The OEKRF model achieved 93% accuracy in Scenario III that shows the strong ability of prediction for assessment of toxicity. Higher values of coefficient of correlation and coefficient of determination makes the model reliable for assessing toxic and non-toxic compounds. Low values of MAE and RMSE make the model compatible for real world applications where prediction of toxicity plays an important role for drug development and predictions at early stage reduces the requirement of extensive testing and saves resources and time.

State of art parameters for all the three scenarios is presented. Figure 11 presents the comparison of R and COD values; Fig. 12 presents comparison of MAE and RMSE values; Fig. 13 is representing accuracy; and Fig. 14 is presenting saw scores with highest and lowest scores.

When the optimized ensembled model KRF itself is compared in three different scenarios, it performs exceptionally well in scenario III with feature selection, resampling, and 10 F-CV.

Conclusion

Prediction of toxicity has been quite a challenging and crucial task from the start of the medical era. But now AI and ML brought a revolution in the healthcare industry. It is possible to optimize this challenging task now. We developed an optimized ensembled toxicity prediction model KRF in the research. We evaluated and compared state of art parameters for seven machine learning algorithms along with the optimized model. The optimized ensembled model performs well in all three scenarios mentioned in the presented work. Scenario-wise results are shown in the paper with evaluated values of state of art parameters. An optimized model performs exceptionally well in all the scenarios, But when compared to the model itself in all three scenarios, scenario III performs best in all the aspects. Deep learning algorithms are also introduced to compare with the optimized model. The optimized ensembled KRF achieves the highest accuracy of 93% in scenario III which was best in comparison to scenario I and scenario II with values of 77% and 89% respectively. The R value, COD value, MAE value, and RMSE values are 0.93, 0.86, 0.07, and 0.25 respectively for scenario III. Further W-saw and L-saw values for scenario III are 0.91 and 0.16 respectively. So the results are established and validated for all the scenarios but on applying feature selection, resampling, and 10 F-CV technique results are best and optimized. The future prospect of the proposed model (OEKRF) is to easily adopt the sudden changes and works in the dynamic environment and learn from large historical data to identify the patterns which helps to extend the model generalization for unseen data. In the coming era, results can be optimized by using new machine learning algorithms. Optimized combinations of features can be introduced by using new feature selection methods. Ensembling of more algorithms can be performed and results can be analyzed by using new parameters. Although the performance of the model is quite satisfactory but further there is a scope of improvement that leads to use computational science such as automata theory to reduce the computational overhead, recommendation at every level and explore all the possibilities with corresponding solutions.

Data availability

Data is available within the manuscript and further can be requested from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Antelo-Collado, A., Carrasco-Velar, R. & García-Pedrajas, N. Cerruela-García, G. Effective feature selection method for Class-Imbalance datasets applied to chemical toxicity prediction. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61, 76–94 (2021).

He, L. et al. Insights into pesticide toxicity against aquatic organism: QSTR models on Daphnia Magna. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 173, 285–292 (2019).

Sharma, D., Singh Aujla, G. & Bajaj, R. Evolution from ancient medication to human-centered healthcare 4.0: A review on health care recommender systems. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 36, 1–40 (2023).

Karim, A. et al. Quantitative toxicity prediction via meta ensembling of multitask deep learning models. ACS Omega. 6, 12306–12317 (2021).

Mistry, P. et al. Prediction of the effect of formulation on the toxicity of chemicals. Toxicol. Res. (Camb). 6, 42–53 (2017).

Wu, Y. & Wang, G. Machine learning based toxicity prediction: from chemical structural description to transcriptome analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 2358 (2018).

Usak, M. et al. Health care service delivery based on the internet of things: A systematic and comprehensive study. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 33, 1–17 (2020).

Baker, N. C. et al. Characterizing cleft palate toxicants using ToxCast data, chemical structure, and the biomedical literature. Birth Defects Res. 112, 19–39 (2020).

Uçar, M. K. Classification Performance-Based feature selection algorithm for machine learning: P-Score. Irbm 41, 229–239 (2020).

Takci, H. Improvement of heart attack prediction by the feature selection methods. Turkish J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 26, 1–10 (2018).

Chen, J., Zeng, Y., Li, Y. & Huang, G. Bin. Unsupervised feature selection based extreme learning machine for clustering. Neurocomputing 386, 198–207 (2020).

Babaagba, K. O. & Adesanya, S. O. A study on the effect of feature selection on malware analysis using machine learning. ACM Int. Conf. Proceeding Ser. Part F1481, 51–55 (2019).

Roy, S. D., Das, S., Kar, D., Schwenker, F. & Sarkar, R. Computer aided breast cancer detection using ensembling of texture and statistical image features. Sensors 21, 1–17 (2021).

Gormez, Y., Aydin, Z., Karademir, R. & Gungor, V. C. A deep learning approach with bayesian optimization and ensemble classifiers for detecting denial of service attacks. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 33, 1–16 (2020).

Sumonja, N., Gemovic, B., Veljkovic, N. & Perovic, V. Automated feature engineering improves prediction of protein–protein interactions. Amino Acids. 51, 1187–1200 (2019).

Greenstein-Messica, A. & Rokach, L. Machine learning and operation research based method for promotion optimization of products with no price elasticity history. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 40, 100914 (2020).

Raghuwanshi, B. S. & Shukla, S. Classifying imbalanced data using BalanceCascade-based kernelized extreme learning machine. Pattern Anal. Appl. 23, 1157–1182 (2020).

Smith, M. R. & Martinez, T. The robustness of majority voting compared to filtering misclassified instances in supervised classification tasks. Artif. Intell. Rev. 49, 105–130 (2018).

Shah, B., Dalwadi, G., Pandey, A., Shah, H. & Kothari, N. Online CQI-based optimization using k-means and machine learning approach under sparse system knowledge. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 33, 1–13 (2020).

Abraham, B. et al. A comparison of machine learning approaches to detect botnet traffic. Proc. Int. Jt. Conf. Neural Networks. 2018-July, 1–8 (2018).

Hooda, N., Bawa, S. & Rana, P. S. Optimizing fraudulent firm prediction using ensemble machine learning: A case study of an external audit. Appl. Artif. Intell. 34, 20–30 (2020).

Pham, T. H. et al. Fusion of B-mode and shear wave elastography ultrasound features for automated detection of axillary lymph node metastasis in breast carcinoma. Expert Syst. 39, 1–19 (2022).

Alwadi, M., Chetty, G. & Yamin, M. A framework for vehicle quality evaluation based on interpretable machine learning. Int. J. Inf. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41870-022-01121-6 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Development of novel prediction model for drug-induced mitochondrial toxicity by using Naïve Bayes classifier method. Food Chem. Toxicol. 110, 122–129 (2017).

Sukumaran, C. et al. The Role of AI in Biochips for Early Disease Detection, 2023 3rd International Conference on Technological Advancements in Computational Sciences (ICTACS), Tashkent, Uzbekistan, pp. 1323–1328, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICTACS59847.2023.10390419

Sarwar, A., Ali, M., Manhas, J. & Sharma, V. Diagnosis of diabetes type-II using hybrid machine learning based ensemble model. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 12, 419–428 (2020).

Verma, K. K., Singh, B. M. & Dixit, A. A review of supervised and unsupervised machine learning techniques for suspicious behavior recognition in intelligent surveillance system. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 14, 397–410 (2022).

Bojamma, A. M. & Shastry, C. A study on the machine learning techniques for automated plant species identification: current trends and challenges. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 13, 989–995 (2021).

Shidnal, S., Latte, M. V. & Kapoor, A. Crop yield prediction: two-tiered machine learning model approach. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 13, 1983–1991 (2021).

Gini, G., Benfenati, E. & Boley, D. Clustering and classification techniques to assess aquatic toxicity. 4th Int. Conf. Knowledge-Based Intell. Eng. Syst. Allied Technol. KES 2000 - Proc. 1, 166–172 (2000).

Zhang, L. et al. Applications of machine learning methods in drug toxicity prediction. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 18, 987–997 (2018).

Basile, A. O., Yahi, A. & Tatonetti, N. P. Artificial intelligence for drug toxicity and safety. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 40, 624–635 (2019).

Borrero, L. A., Guette, L. S., Lopez, E., Pineda, O. B. & Castro, E. B. Predicting toxicity properties through machine learning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 170, 1011–1016 (2020).

Hooda, N., Bawa, S. & Rana, P. S. B2FSE framework for high dimensional imbalanced data: A case study for drug toxicity prediction. Neurocomputing 276, 31–41 (2018).

Parker, A. J. & Barnard, A. S. Selecting appropriate clustering methods for materials science applications of machine learning. Adv. Theory Simulations. 2, 1–8 (2019).

Prabagar, S., Al-Jiboory, A. K., Nair, P. S., Mandal, P. & Garse, K. M. N. L, Artificial Intelligence-Based Control Strategies for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, 10th IEEE Uttar Pradesh Section International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Engineering (UPCON), Gautam Buddha Nagar, India, 2023, pp. 1624–1629, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/UPCON59197.2023.10434918

Gajewicz-Skretna, A., Furuhama, A., Yamamoto, H. & Suzuki, N. Generating accurate in Silico predictions of acute aquatic toxicity for a range of organic chemicals: towards similarity-based machine learning methods. Chemosphere 280, 130681 (2021).

Ai, H. et al. QSAR modelling study of the bioconcentration factor and toxicity of organic compounds to aquatic organisms using machine learning and ensemble methods. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 179, 71–78 (2019).

Pathak, Y., Rana, P. S., Singh, P. K., & Saraswat, M. Protein structure prediction (RMSD≤ 5 Å) using machine learning models. International Journal of Data Mining and Bioinformatics, 14, 71–85 (2016).

Mishra, S., & Ahirwar, A. Comparative study of machine learning models in protein structure prediction. Int J Comput Sci Inf Technol, 6, 5398–5404 (2015).

Aagashram Neelakandan, A. S. A., Doss, N. & Lakshmaiya Computational design exploration of rocket nozzle using deep reinforcement learning. Results Eng. 25, 104439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2025.104439 (2025).

Tran, T. T., Van, S., Wibowo, A., Tayara, H. & Chong, K. T. Artificial intelligence in drug toxicity prediction: recent advances, challenges, and future perspectives. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 63, 2628–2643 (2023).

Akbar, S., Raza, A. & Zou, Q. Deepstacked-AVPs: predicting antiviral peptides using tri-segment evolutionary profile and word embedding based multi-perspective features with deep stacking model. BMC Bioinform. 25, 102 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Deepak Rawat, Rohit Bajaj, Rachit Manchanda, Ankush Mehta– Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Former Analysis, Writing Original Draft, Funding Acquisition, Project Administration. Prabhu Paramasivam, Suraj Kumar Bhagat, Abinet Gosaye Ayanie – Validation, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Supervision, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

All the authors have given consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rawat, D., Bajaj, R., Manchanda, R. et al. A robust and statistical analyzed predictive model for drug toxicity using machine learning. Sci Rep 15, 17993 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02333-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02333-z