Abstract

This study demonstrates that the modified frailty index-6 (mFI-6) is a useful tool for predicting the completion of S-1 adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) and associated adverse events (AEs) in patients with pancreatic cancer (PC). mFI-6 is an index that incorporates serum albumin levels into the existing mFI-5, enabling the assessment of patients’ ability to complete S-1 therapy and their risk of developing AEs. This study retrospectively analyzed PC patients from two university hospitals between August 2013 and July 2022. Patients from one hospital were assigned to the testing dataset, while those from the other hospital were used as the validation dataset. Patients were classified as frail if they met at least two of the six criteria, including a serum albumin level of < 3.5 g/dL. In the testing cohort (n = 86 PC patients), frailty patients exhibited greater difficulty in completing S-1 therapy compared to non-frail patients, with a significantly lower completion rate (p = 0.003). Additionally, frail patients demonstrated significantly shorter recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) compared to their non-frail counterparts. The findings were further validated in the validation dataset, where frail patients exhibited a lower S-1 completion rate and significantly shorter RFS (p = 0.023) and overall survival (OS) (p = 0.045). These results suggest that mFI-6 may be an effective tool for postoperative frailty screening, allowing healthcare professionals to assess patients’ tolerance to S-1 therapy and adjust treatment plans accordingly. Ultimately, the implementation of this index may contribute to improving clinical outcomes for patients with PC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background

Frailty is a multifaceted medical condition characterized by augmented vulnerability and decreased physiological resilience. It is often associated with aging and the presence of chronic health conditions. Frailty encompasses an array of physical, psychological, and functional dysfunctions. It renders individuals more susceptible to adverse health outcomes, including disability, prolonged hospitalization, and increased morbidity and mortality.

Frailty has evolved into a comprehensive concept that includes sarcopenia and malnutrition1. Various approaches have been developed to assess frailty. Originally, an index that consisted of > 70 risk factors was established by the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Programs (ACS NSQIP), which was pared down to 11 comorbidities to form a modified frailty index-11 (mFI-11)2. An alternative and simpler version, known as mFI-5, includes the following five specific comorbidities: diabetes mellitus (DM), congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or recent pneumonia, hypertension requiring medication (HT), and non-independent functional status3. Recent empirical findings revealed an association between the mFI-5 parameters and adverse outcomes as well as postoperative complications (POCs)4.

Rationale and knowledge gap

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is one of the most aggressive cancers associated with a poor prognosis. Despite advancements in surgical methods and perioperative regimens, the 5-year survival rate is only 9% in the United States for cases that require only surgery5. Surgical resection remains the only curative option for PC; however, the poor prognosis of PC is mainly based on a higher frequency of early postoperative recurrence, which is observed in nearly 80% of patients within the first postoperative 12 months6. To improve outcomes, several clinical trials of adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) have been conducted in patients with PC who underwent radical surgery7,8.

The Japanese guidelines were elaborated based on these data, and orally administered S-1 for AC following radical surgery was included9. This recommendation stems from the Japan Adjuvant Study Group of Pancreatic Cancer (JASPAC)-01 trial, which demonstrated a longer 5-year survival rate for patients with S-1 compared with those who underwent gemcitabine therapy after radical intervention10. Nevertheless, PC incidence is higher among older adults. Therefore, the proportionate number of individuals opting for AC is notably limited11. Furthermore, even among those who present with early-stage PC, challenges still arise with a continuous intake of S-1 due to POCs or AC-related adverse events (AEs)12.

The completion rate for AC involving S-1 therapy is approximately 65%13,14. Recent findings suggest that nutritional status is an effective predictive marker for the completion of S-1 therapy15,16. Furthermore, frailty has a close connection with nutritional status17. Thus, frailty and nutritional status have a high potential to predict various patient outcomes. Despite frailty encompassing nutritional states, such as sarcopenia and malnutrition, mFI-5 does not include markers of nutritional status. Therefore, we hypothesized that mFI-5 and lower serum albumin levels may serve as a robust predictive index (mFI-6) to determine patients’ tolerance for S-1 therapy before initiation of AC (Fig. 1).

Correlation diagram between nutritional status, incorporating frailty, and patient outcomes. This figure illustrates how frailty, particularly when incorporating nutritional components such as sarcopenia and hypoalbuminemia, is associated with increased risk of postoperative complications (POCs), severe adverse events (AEs), and poor survival outcomes in pancreatic cancer patients.

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate the association between the completion of S-1 and a postoperative mFI-6 score in a testing cohort (Ehime study). In addition, a separate university hospital cohort for validation (Dokkyo study) was involved.

Methods

Study population and data collection

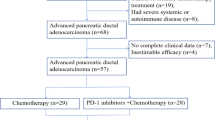

This retrospective Ehime study included 153 consecutive patients who underwent curative surgery for PC at Ehime University Hospital between August 2013 and July 2022. Of these, 67 patients who were not treated with S-1 treatment or experienced early recurrence with a radiological appearance of new metastatic tumors before or during AC treatment were excluded (Fig. 2). As a result, 86 patients were enrolled in the testing cohort. Patient medical records were reviewed, including background information, perioperative laboratory and clinical data, pathological findings, POCs, and survival. The mFI-5 and mFI-6 indices were calculated by assigning one point for each of the following comorbidities present: DM, CHF, COPD or recent pneumonia, HT requiring medication, functionally independent status, and serum albumin levels.

The score sum was then divided by five or six to yield each patient’s mFI-5 (range 0–5) and mFI-6 score (range 0–6), respectively. Patients were then divided according to mFI-6 scores into two groups: 0–1 (no-frailty group) and ≥ 2 (frailty group). In the Dokkyo study for validation cohort, 230 consecutive patients who underwent curative surgery for PC at Dokkyo Medical University Hospital during the same period were registered. Of these, 83 patients who did not undergo S-1 treatment or 36 patients who experienced early recurrence with metastatic tumors before or during AC treatment were excluded (Fig. 3). As a result, 111 patients were included in the validation cohort. POCs were graded according to the Clavien–Dindo classification, and grade ≥ 3 complications were defined as major POCs18.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the concerned institutional ethics committees, with a waiver of written informed consent from the patients. The study was conducted following the ethical guidelines of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was described on Ehime University Hospital’s website, and participants were allowed to opt out of the study.

S-1 AC schemes and oncologic surveillance

AC was promptly initiated after hospital discharge and lasted for 6 months. In most patients, AC was initiated within 3 months following curative surgery. The treatment protocol involved orally administered S-1, with doses ranging from 80 to 120 mg based on the patient’s body surface area. The dose was administered twice daily for 28 days, which was followed by a 14-day rest period, or for 14 days, which was followed by a 7-day rest period. The treatment cycles were repeated for 6 months until unacceptable levels of toxicity were observed. The relative dose intensity (RDI) was determined by comparing the prescribed S-1 dose intensity to a standard or planned dose intensity19. Consistent oral intake with an RDI of ≥ 80% was considered a satisfactory completion of the S-1 regimen20. Blood biochemistry and clinical symptoms, including changes in body weight, were analyzed at the onset of AC and during subsequent appointments. Oncologic surveillance included contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans every 3 months. AEs were graded using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0, with AEs of Grade ≥ 3 considered severe21.

Definition of mFI-6

mFI-6 score was calculated using six variables. Of these, the original five variables were from the mFI-5 index established by ACS NSQIP. These variables included CHF, COPD or recent pneumonia, HT, DM, and non-independent functional status. In addition, serum albumin levels (< 3.5 g/dL) before AC was added as an additional metric. Therefore, the novel mFI-6 was scored on a scale from 0 to 6. Frailty was defined as an mFI-6 \(\ge\) 2. Patients were assigned to two groups, namely S-1 complete and incomplete, or non-frailty and frailty groups, after calculating mFI-6.

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney U-test was used for continuous variables that exhibited a normal distribution. Conversely, chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were applied for the comparative analysis of categorical data between patients with non-frailty and frailty, and S-1 complete and incomplete groups, respectively. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was done to determine the risk of S-1 incompletion. The optimal cutoff values for CRP, CA19-9, age, and albumin level were determined based on the results of the ROC curve analysis, with the Youden index used to calculate the cutoff values for all variables. Disease-free survival (DFS) and overall Survival (OS) rates were assessed by the Kaplan–Meier method, and S-1 complete and incomplete groups or non- and frailty were juxtaposed using the log-rank test; p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to assess the prognostic impact of variables on DFS and OS. All statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS®) v.16.0 for Windows® (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) or GraphPad Prism v.5.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Comparison of patient groups based on the completion of S-1 therapy (Ehime study)

Patients (N = 88) who were subjected to radical surgery for PC were enrolled in the Ehime study (Testing cohort). A significantly higher number of patients with frailty, who were defined by the mFI-6 index, were observed (p = 0.003) in the S-1 incomplete group. However, no significant differences were observed based on gender, age, surgical procedure, pathological stage, or severe POC rates between the groups divided based on S-1 completion (Table 1).

Comparison of areas under the curve through receiver operating characteristic analysis (Ehime study)

ROC analysis revealed that the areas under the curve (AUC) for mFI-5, and mFI-6 were 0.71 and 0.78, respectively (Fig. 4). Thus, mFI-6 might serve as a useful predictive marker for S-1 completion following surgery. Using the Youden index, an mFI-6 value of two was considered the appropriate cutoff, with a sensitivity of 77.8% and a specificity of 65.7%.

Association between S-1 completion and patient prognosis (Ehime study)

Similar to the results of JASPAC-110, the S-1 completion group in the Ehime cohort exhibited significantly higher DFS rates (p = 0.01, HR: 2.63, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.23–5.62) and OS (p < 0.001, HR: 6.08, 95% CI 2.79–13.28) compared with the S-1 incompletion group (Fig. 5).

Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing S-1 completion and incompletion in the Ehime study. The left panel shows disease-free survival (DFS), and the right panel shows overall survival (OS) for patients who completed S-1 adjuvant chemotherapy (n = 69, red) versus those who did not (n = 17, black). Patients in the S-1 complete group had significantly better DFS (P = 0.010, HR = 2.63) and OS (P < 0.001, HR = 6.08) compared to the S-1 incomplete group.

Comparison of patient groups based on frailty score according to mFI-6 (Ehime study)

Overall, 49 patients with an mFI-6 score of < 1 were classified into the non-frailty group, and 37 with an mFI-6 score of ≥ 2 were categorized into the frailty group. Although no significant differences were observed in perioperative factors based on the presence of frailty, significant differences were noted between the groups in terms of S-1 completion rate (p = 0.003) and grade 3 or higher AEs (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis

Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that mFI-6 ≥ 2(p = 0.028) and CRP > 0.25 (p = 0.006) were independent potential markers for S-1 incompletion, as outlined in Table 3.

Association between frailty and patient prognosis (Ehime study)

The assessment of frailty status in the Ehime study using mFI-6 revealed a significant association with prognosis (Fig. 6). The non-frail group demonstrated a longer DFS and OS than the frail group. Clinically significant improvement in median DFS and OS benefits were observed, HR: 2.28 and 2.12; [95% CI 1.12–4.42, and 1.00–4.49]; p value = 0.013, and 0.044). This indicates that frailty, as determined by mFI-6, has an important role in determining patient outcomes, thus underscoring its potential value for prognostic evaluation.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing frailty and non-frailty groups based on mFI-6 in the Ehime cohort. The left panel displays disease-free survival (DFS), and the right panel shows overall survival (OS) for patients classified as frail (mFI-6 ≥ 2, n = 37, red) and non-frail (mFI-6 ≤ 1, n = 49, black). Frail patients demonstrated significantly shorter DFS (P = 0.013, HR = 2.28) and OS (P = 0.044, HR = 2.12) compared to non-frail patients.

Comparison of patient groups based on the completion status of S-1 therapy (Dokkyo study)

In the Dokkyo study, 111 patients who were subjected to radical surgery for PC were included in the validation cohort and divided into two groups based on completion of S-1 therapy (N = 76). The S-1 incompletion group (N = 35) had a significantly higher frailty incidence, as defined by mFI-6 (p < 0.001) (Table 4). Furthermore, the non-frail group demonstrated a longer DFS and OS than the frail group. Clinically significant improvement in median DFS and OS benefits was observed, HR: 2.67 and 3.14; [95% CI 1.67–4.28, and 1.88–5.24]; p value < 0.001, and < 0.001) (Fig. 7).

Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing S-1 completion and incompletion in the Dokkyo cohort (Validation cohort). The left panel shows disease-free survival (DFS), and the right panel shows overall survival (OS) for patients who completed S-1 adjuvant chemotherapy (n = 69, red) versus those who did not (n = 17, black). The S-1 complete group exhibited significantly better DFS (P < 0.001, HR = 2.67) and OS (P < 0.001, HR = 3.13) compared to the incomplete group.

Comparison of patient groups based on the frailty score according to mFI-6 (Dokkyo study)

In total, 67 patients with an mFI-6 score of ≤ 1 were categorized into the non-frailty group and 44 patients with an mFI-6 score of ≥ 2 were assigned to the frailty group. Although no statistically significant differences were observed in perioperative parameters between the indicated groups, significant differences were evident in the rates of S-1 incompletion and the occurrence of grade 3 or higher AEs between the two groups (Table 4).

The association between frailty and patient prognosis (Dokkyo study)

The analysis of frailty status in the Dokkyo cohort using the mFI-6 index revealed a significant association with DFS and OS. Patients classified as frail had significantly poorer DFS and OS compared to non-frail patients (p = 0.023, HR: 1.96, 95% CI 1.24–3.12 for DFS, p = 0.045, HR: 1.97, 95% CI 1.18–3.26 for OS), as shown in Fig. 8. However, it should be noted that this study was primarily designed to assess mFI-6 as a predictive factor for S-1 completion, not as a prognostic factor. Therefore, these survival differences are considered secondary observations.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing frailty and non-frailty groups based on mFI-6 in the Dokkyo cohort (Validation cohort). The left panel shows disease-free survival (DFS), and the right panel shows overall survival (OS) for patients classified as frail (mFI-6 ≥ 2, n = 67, red) and non-frail (mFI-6 ≤ 1, n = 44, black). Frail patients had significantly worse DFS (P = 0.023, HR = 1.96) and OS (P = 0.045, HR = 1.97) than non-frail patients.

Comparison of severe adverse events between Ehime and Dokkyo cohorts

Table 5 summarizes the details of severe AEs in both cohorts. AEs varied widely, and no notable differences in specific AEs were observed between the two cohorts.

Discussion

Our Ehime study suggested that mFI-6, which incorporates serum albumin levels into the original mFI-5, serves as a predictive factor for S-1 AC completion. Furthermore, similar results were validated in the Dokkyo study, reinforcing the potential utility of mFI-6 in predicting S-1 completion.

Frailty epitomizes the convergence of debility, senescence, and vulnerability within the realm of human health. It delineates a condition marked by a gradual decline in physical and cognitive resilience, including motor and cognitive faculties, due to aging. This degeneration often results in compromised daily functionality and increased susceptibility to both physical and mental health challenges. Furthermore, frailty is a precursor to a care-dependent state and is associated with higher risks of adverse health outcomes, including reduced independence and mortality1.

Various diagnostic tools have been proposed to identify patients with frailty; however, none have been fully adopted, partially because of assessment challenges and the intricacies of the evaluation process. Thus, there is a need for a streamlined frailty assessment method that is clinically relevant and circumvents the complexities inherent in extant approaches.

The mFI-11 and mFI-5 indices established by the ACS NSQIP database show a correlation with morbidity and mortality across various surgical disciplines, including vascular surgery3,22. In particular, mFI-5 offers a simplified yet efficacious method for frailty assessment and is useful as a more clinically concise and user-friendly index compared with mFI-113. Subsequently, mFI-5 has emerged as a pivotal predictive factor for POCs and patient prognoses as evidenced in recent studies23. Notably, several studies underscore the role of frailty in predicting AEs associated with chemotherapy24,25. Moreover, a recent report indicates a close connection between frailty and nutritional status because the former encompasses the latter within its purview17. Evidence linking frailty to outcomes including POCs and prognosis is present. When considering the relationship between frailty and pancreatic tumors, frailty is a predictive factor for patient outcomes including POCs and S-1 completion26,27. However, reports have not yet confirmed an association between chemotherapeutic toxicity and frailty in PC, warranting further data accumulation. Conversely, preoperative nutritional status, which incorporates indices such as the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index28,29, Prognostic Nutritional Index30, and C-reactive protein-to-albumin ratio31, has attracted attention for establishing a link between the prognosis of the patient with cancer and the incidence of POCs. Similarly, these nutritional indices also serve as prognostic factors for chemotherapeutic AEs32. As demonstrated above and in Fig. 1, frailty and nutritional status, including sarcopenia, are closely intertwined with patient outcomes, such as POCs, chemotherapeutic AEs, and other events outlined in the patient’s survival.

Our recent studies revealed a significant correlation between nutritional indicators, such as GNRI (geriatric nutritional risk index) and C-reactive protein/albumin ratio, and the incidence of AEs associated with S-1 treatment. Our results indicate that individuals within malnourished cohorts experience more pronounced AEs and exhibit poorer outcomes, as evidenced by considerably lower DFS and OS rates15,16. These findings reveal the complex interaction between nutritional stats, treatment adherence, and overall prognosis in S-1 therapy.

The JASPAC-01 report from Japan emphasized the efficacy of S-1 chemotherapy in adjuvant regimens, which established its use as a standard treatment10. Generally, patients from Asia exhibit higher adherence to S-1 therapy compared with their Caucasian counterparts33. Consequently, ensuring an uninterrupted continuation of S-1 AC for six months is an important determinant of prognosis, as discontinuing S-1 therapy is associated with a higher frequency of adverse outcomes. Numerous cases evaluating the completion of S-1 treatment have been documented. Yamada et al. revealed that a low PNI score during the initial visit is a significant factor influencing AC completion with S-134. Furthermore, Matsumoto et al. examined the postoperative phase and found that serum albumin levels were important indicators during this period for predicting the likelihood of failing to complete AC with S-135. Taken together, these results underscore the key role of postsurgical malnutrition in decreasing AC compliance, which is primarily revealed in the occurrence of severe AEs. This compromised adherence, in turn, is associated with a poorer prognosis36.

Based on the intricate interplay between nutritional status, frailty, and patient outcomes, we hypothesize that mFI-6 may serve as a valuable tool for predicting AEs that result from S-1 therapy. Moreover, we posited that this extended version, which incorporates low albumin as an additional factor, might potentially enhance its predictive value.

The present study supports this hypothesis by demonstrating the utility of mFI-6 as an effective predictor of AEs associated with S-1 treatment. This highlights its potential clinical value and also suggests its applicability in real-world settings as a convenient and noninvasive approach to evaluating and predicting AEs. Our findings support the prospect of integrating the mFI-6 application into routine clinical practice for improved risk stratification and patient care.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the correlation between frailty and the completion of S-1 therapy in patients with PC following curative surgery. A key novelty of this study is the use of mFI-6, which incorporates albumin levels as an additional parameter compared to the conventional mFI-5. By including albumin, our study enhances the ability to identify frail patients more accurately. Furthermore, this is the first study to demonstrate that mFI-6 serves as a predictive factor for the completion of S-1 AC. These findings highlight the clinical utility of mFI-6 in optimizing treatment strategies and improving patient management in postoperative PC care. The results of this study demonstrate that frailty patients tend to have lower completion rates for S-1 AC, with a completion rate of approximately 50–65%. Therefore, it is crucial to provide careful follow-up for frailty patients, considering the risk of treatment interruption due to AEs associated with AC. Moreover, frailty is widely recognized as an indicator of poor prognosis; however, recent studies have suggested that frailty may also be a contributing factor to the incomplete adherence to AC37. Furthermore, frailty is associated with POCs, and interventions such as nutritional support and physical exercise have shown promise in preventing these POCs38. These findings underscore the importance of a multifaceted approach aimed at improving the frailty state postoperatively, and incorporating nutritional interventions is expected to enhance the completion rate of AC.

Moving forward, we plan to evaluate the impact of postoperative interventions, including nutritional therapy and exercise, on AC completion rates in frailty patients with PC through a prospective study. Such studies are expected to contribute not only to the optimization of personalized treatment strategies but also to the improvement of clinical outcomes in frailty patients with PC. Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge several limitations to our study: (i) The retrospective nature of the enrolled patient cohort, despite the inclusion of the validation cohort, has the potential for institutional biases, and the generalizability of our findings may be constrained. (ii) The relatively limited number of patients underscores a constraint in the robustness of the study. (iii) Throughout the administration of AC, patients adhered to outpatient clinic visits at intervals of 4–6 weeks. Consequently, the reporting of AEs might be subject to underestimation as some patients may not have disclosed AEs unless they coincided with their scheduled appointments. (iv) The specifics of S-1 administration and encompassing factors, such as the timing of initiation, dosage, dose reduction, and discontinuation, were established at the discretion of the attending physician. Thus, the need for validation is necessary through comprehensive, large-scale trials. Considering these limitations, a prudent approach to interpretation is necessary, and future validation studies with more extensive and diverse cohorts are warranted to confirm our findings.

Conclusions

mFI-6 may be a useful predictive marker for S-1 AC completion; however, further validation is required. If established as a robust predictive tool, it would enable clinicians to identify patients at higher risk of failing to complete S-1 therapy due to adverse events (AEs). Additionally, it could serve as a strategic tool for clinicians to proactively recognize patients who are predisposed to not completing S-1 therapy, allowing for timely interventions and personalized treatment strategies. Given the retrospective design and limited sample size, further prospective validation studies are warranted.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Tolley, A. P. L., Ramsey, K. A., Rojer, A. G. M., Reijnierse, E. M. & Maier, A. B. Objectively measured physical activity is associated with frailty in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 137, 218–230 (2021).

Velanovich, V., Antoine, H., Swartz, A., Peters, D. & Rubinfeld, I. Accumulating deficits model of frailty and postoperative mortality and morbidity: its application to a national database. J. Surg. Res. 183, 104–110 (2013).

Traven, S. A., Reeves, R. A., Slone, H. S. & Walton, Z. J. Frailty predicts medical complications, length of stay, readmission, and mortality in revision hip and knee arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 34, 1412–1416 (2019).

McGovern, J. et al. The relationship between the modified frailty index score (mFI-5), malnutrition, body composition, systemic inflammation and short-term clinical outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer. BMC Geriatr. 23, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03703-2 (2023).

Allemani, C. et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000–14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet 391, 1023–1075 (2018).

Groot, V. P. et al. Defining and predicting early recurrence in 957 patients with resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. 269, 1154–1162 (2019).

Neoptolemos, J. P. et al. Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 389, 1011–1024 (2017).

Miyazawa, M. et al. Phase II clinical trial using novel peptide cocktail vaccine as a postoperative adjuvant treatment for surgically resected pancreatic cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer 140, 973–982 (2017).

Japan Pancreas Society. Clinical practice guidelines for pancreatic cancer. 2019, Available from: http://www.suizou.org/pdf/pancreatic_cancer_cpg-2019.pdf (in Japanese)

Uesaka, K. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy of S-1 versus gemcitabine for resected pancreatic cancer: a phase 3, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial (JASPAC 01). Lancet 388, 248–257 (2016).

Nagrial, A. M. et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients with pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 110, 313–319 (2014).

Ueno, H. et al. A randomised phase III trial comparing gemcitabine with surgery-only in patients with resected pancreatic cancer: Japanese study group of adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 101, 908–915 (2009).

Kayashima, H. et al. Effect of duration of adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 (6 versus 12 months) for resected pancreatic cancer: the multicenter clinical randomized phase II postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy S-1 (PACS-1) trial. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, 1520–1529 (2023).

Yamamoto, H. et al. Randomized phase II study of daily versus alternate-day administrations of S-1 for the elderly patients with completely resected pathological stage IA (tumor diameter > 2 cm)-IIIA of non-small cell lung cancer: Setouchi lung cancer group study 1201. PLoS ONE 18, e0285273. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285273 (2023).

Sakamoto, A. et al. Geriatric nutritional risk index predicts tolerability of S-1 as adjuvant chemotherapy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 52, e196–e202 (2023).

Funamizu, N. et al. C-reactive protein-to-albumin ratio to predict tolerability of S-1 as an adjuvant chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Cancers 16, 922. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16050922 (2024).

Moradell, A. et al. Functional frailty, dietary intake, and risk of malnutrition: are Nutrients involved in muscle synthesis the key for frailty prevention?. Nutrients 13, 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13041231 (2021).

Dindo, D., Demartines, N. & Clavien, P. A. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann. Surg. 240, 205–213 (2004).

Valle, J. W. et al. Optimal duration and timing of adjuvant chemotherapy after definitive surgery for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: ongoing lessons from the ESPAC-3 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 504–512 (2014).

Qi, W. et al. The effect of reduced RDI of chemotherapy on the outcome of breast cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 10, 13241. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70187-8 (2020).

United States Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). version 5 (National Cancer Institute, 2017).

Karam, J., Tsiouris, A., Shepard, A., Velanovich, V. & Rubinfeld, I. Simplified frailty index to predict adverse outcomes and mortality in vascular surgery patients. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 27, 904–908 (2013).

An, S., Eo, W. & Lee, S. Prognostic significance of a five-factor modified frailty index in patients with gastric cancer undergoing curative-intent resection: a cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 102, e36065. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000036065 (2023).

Baltussen, J. C. et al. Chemotherapy-related toxic effects and quality of life and physical functioning in older patients. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2339116. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.39116 (2023).

Djebbari, F. et al. Evaluation of the frailty characteristics and clinical outcomes according to the new frailty-based outcome prediction model (myeloma risk profile-MRP) in a UK real-world cohort of elderly newly diagnosed myeloma patients. PLoS ONE 17, e0262388. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262388 (2022).

Mima, K. et al. Frailty is associated with poor prognosis after resection for pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 1938–1946 (2021).

Ninomiya, G. et al. Clinical impact of sarcopenia on prognosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 39, 45–51 (2017).

Hayama, T. et al. The preoperative Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) is an independent prognostic factor in elderly patients underwent curative resection for colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 12, 3682. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07540-6 (2022).

Funamizu, N. et al. Geriatric nutritional risk index as a potential prognostic marker for patients with resectable pancreatic cancer: a single-center, retrospective cohort Study. Sci. Rep. 12, 13644. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-18077-z (2022).

Yang, C. K. et al. Prognostic value of geriatric nutritional risk index and prognostic nutritional index in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 59, 355–364 (2024).

Funamizu, N. et al. Association between the preoperative C-reactive protein-to-albumin ratio and the risk for postoperative pancreatic fistula following distal pancreatectomy for pancreatic cancer. Nutrients 14, 5277. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245277 (2022).

Aoki, T., Mori, S. & Kubota, K. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: literature review and our experience of NAC-GS. Cancers 16, 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16050910 (2024).

Chuah, B. et al. Comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of S-1 between Caucasian and East Asian patients. Cancer Sci. 102, 478–483 (2011).

Yamada, D. et al. The basal nutritional state of PDAC patients is the dominant factor for completing adjuvant chemotherapy. Surg. Today 47, 1361–1371 (2017).

Matsumoto, I. et al. Postoperative serum albumin level is a marker of incomplete adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 22, 2408–2415 (2015).

Asano, T. et al. The Charlson age comorbidity index predicts prognosis in patients with resected pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Surg. 39, 169–175 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. The impact of frailty on chemotherapy intolerance in patients with cervical cancer: a longitudinal study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 74, 102725 (2025).

Christopher, C. N. et al. Exercise and nutrition interventions for prehabilitation in hepato-pancreato-biliary cancers: a narrative review. Nutrients 15, 5044 (2023).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Naotake Funamizu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Original draft preparation; Shozo Mori: Data curation; Akimasa Sakamoto: Formal analysis; Masahiko Honjo: Writing—original draft; Kei Tamura: Writing—review & editing; Katsunori Sakamoto: Writing—review & editing; Kohei Ogawa: Writing—review & editing; Yuzo Umeda: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing; Taku Aoki: Writing—review & editing, Project administration; Yasutsugu Takada: Supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Approval of the research protocol

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ehime University Hospital and Dokkyo Medical University Hospital in 2024 (Approval No. EUH2306012) with a waiver of patient informed consent. The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards outlined in the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Funamizu, N., Mori, S., Sakamoto, A. et al. Novel modified frailty index predicts completion of adjuvant chemotherapy in resectable pancreatic cancer in a dual center study. Sci Rep 15, 17000 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02365-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02365-5