Abstract

Four nanobodies (VHH1-4SMT3) that target the yeast SUMO protein Smt3p were isolated and characterized. VHH1-4SMT3 bind to Smt3p and Smt3p-tagged proteins with high affinity (Kd: low nM). NMR analysis shows that the four nanobodies all bind near the C-terminus of Smt3p, partially overlapping with the binding site for the SUMO protease Ulp1p. Binding of Smt3p-specific nanobodies impairs Ulp1-mediated cleavage of Smt3p-tagged proteins, with VHH1SMT3 showing complete inhibition. The use of immobilized VHH2SMT3 enabled efficient purification of Smt3p-tagged proteins, while VHH1SMT3 can be used for immunoblotting and detects both Smt3p-tagged and free Smt3p. When expressed in yeast, VHH1SMT3 causes significant growth defects, particularly when targeted to the nucleus or fused with GFP, indicative of interference with essential SUMOylation-dependent processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

SUMOylation is an essential post-translational modification involving the covalent attachment of SUMO (Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier) to lysine residues in target proteins. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the SUMO protein (Smt3p) is encoded by the SMT3 (Suppressor of Mif Two 3) gene1,2. The SUMO conjugation cascade comprises a single dimeric E1 (Sae1p-Uba2p, activating), a single E2 (Ubc9p, conjugating), and several E3-type (ligase) enzymes2,3. The targets for SUMOylation are predominantly nuclear proteins, and this process is important for maintenance of genome stability and cell cycle control4,5,6,7,8. SUMOylated proteins can be de-SUMOylated by SUMO-specific proteases (Ulp1p and Ulp2p), analogous to the reversal of ubiquitylation by deubiquitinating enzymes2,9,10,11. In yeast, Ulp1p also cleaves the Smt3p precursor to its mature form12. While SUMOylation is a transient and dynamic process that responds to various forms of cellular stress2,3,13,14,15, the process is essential since SMT3 null mutants are lethal16. Current approaches to study SUMOylation include overexpression of tagged SUMO protein, mass spectrometry-based proteomics, conditional SMT3 mutants, and genetic mutants with defects in SUMO-specific proteases15,17,18,19.

Independent of its biological function, yeast SUMO is also used as a fusion tag for improved expression of ‘difficult-to-express’ proteins in bacterial systems to enhance their solubility and folding20,21,22,23,24. The SUMO tag can be removed by scarless cleavage using the SUMO protease Ulp1p20,22. Unlike proteases that recognize specific amino acid sequences, Ulp1p recognizes the tertiary structure of SUMO, preventing unwanted cleavage within the target protein20,25.

Nanobodies are single domain proteins derived from the variable region of heavy chain-only antibodies found in Camelids26,27. They share key properties with conventional antibodies, such as excellent specificity and high binding affinity. Nanobodies have several advantages over conventional antibodies: they are smaller, retain their binding properties in reducing cellular environments, achieve better tissue penetration, and can serve as crystallization chaperones by locking proteins into specific conformations26,27,28.

Here, we develop and characterize nanobodies specific for yeast SUMO and show that they can be used for in vivo perturbation of SUMO-dependent cell growth and a variety of biochemical applications. We identify four anti-SUMO nanobodies (VHH1-4SMT3), characterize their binding properties against SUMO protein and SUMO-tagged proteins, and show that they can be used for affinity chromatography and in immunoblotting. These nanobodies bind near the C-terminus of SUMO, close to the junction on SUMO-tagged fusion proteins. This C-terminal binding of nanobodies on SUMO interferes with Ulp1p cleavage of SUMO-tagged proteins. Their expression in yeast, particularly VHH1SMT3, shows a growth defect, thus providing a novel tool to study SUMOylation in yeast.

Results

Isolation and characterization of nanobodies specific for yeast SUMO (Smt3p)

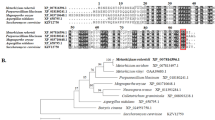

A nanobody library was generated by immunizing an alpaca with N-terminally SUMO-tagged E2 conjugating enzyme (Ube2G2). Screening this library against SUMO-tagged Ube2G2 yielded four nanobodies, designated VHH1-4SMT3 (Fig. 1A) that selectively bound to the SUMO tag (Smt3p) and SMT3p-Ube2G2 fusion protein, but not to untagged Ube2G2 (Supplementary Fig. 1A, Fig. 1B, Fig. 2A). We then characterized these SUMO-specific nanobodies to evaluate their potential as research tools for the detection and study of SUMO-modified proteins. The three complementarity determining regions (CDRs) of VHH1-4SMT3, responsible for binding to target epitopes are indicated in Fig. 1A. Hereafter, we refer to the SUMO tag as Smt3p to denote its yeast origin and to distinguish it from human SUMO proteins.

Nanobodies specific for yeast SUMO (Smt3p) protein and their binding characteristics. (A) Anti-Smt3p nanobody sequences with their complementarity determining regions (CDRs) indicated, based on IMGT database38. The sequence identity for CDR3 in VHH2-4SMT3 suggests a common progenitor, with accumulation of several somatic mutations in its descendants. Using the VHH2SMT3 sequence as the basis for comparison, these somatic mutations are color-coded blue in VHHs 2-4SMT3. (B) Binding of nanobodies to His6- Smt3p as determined by size exclusion chromatography (SEC). Profiles of His6-Smt3p (Blue), VHHs (Green), and an equimolar mixture of Smt3p:VHH (red) are shown. The fractions corresponding to the VHH:Smt3p complex (red peak) were analyzed by SDS PAGE and Native PAGE, as indicated.

All four nanobodies were expressed with high yield and purified to homogeneity using bacterial periplasmic expression, followed by osmotic shock to liberate periplasmic content, with final yields of 30–60 mg/L (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Binding of the nanobodies to purified Smt3p was confirmed by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) and native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (Fig. 1B). SEC of an equimolar Smt3p:VHH mixture (red) revealed a shift towards larger apparent size compared to Smt3p alone (blue), indicating the formation of a complex with a larger Stokes radius. Because nanobodies and Smt3p are very similar in size, we performed native PAGE and denaturing SDS-PAGE for each SEC fraction. In native PAGE, the absence of a polypeptide that corresponds to free Smt3p and the presence of a single band corresponding to the complex confirmed binding (Fig. 1B). Microscale thermophoresis was used to estimate binding affinities, showing that all four nanobodies bind Smt3p with low nanomolar dissociation constants (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 2).

Recognition of Smt3p-tagged proteins by anti- Smt3p nanobodies

To assess ability of nanobodies VHH1-4SMT3 to recognize Smt3p fused to various C-terminal tags and proteins, we purified recombinant Smt3p fused to: (1) a 38 aa Streptavidin binding protein (SBP) tag followed by a 6xHis tag (Smt3p-SBP-His6), (2) Ube2G2 (His6- Smt3p-Ube2G2), and (3) GFP-SBP-His6 (Smt3p-GFP-SBP-His6).

Binding was evaluated by native PAGE at a 2:1 molar ratio of VHH to Smt3p-tagged protein. All four VHHs bound to each of the Smt3p variants, judging from the disappearance of the Smt3p-tagged protein band and the appearance of a higher molecular weight complex (Fig. 2A). Reducing SDS-PAGE of the same samples is shown adjacent to the native PAGE results (Fig. 2A).

Smt3p tagged proteins are recognized by Smt3p-specific VHHs in native PAGE and immunoblot. (A) Left; Native PAGE shows that all four VHHs bind to Smt3p and Smt3p tagged proteins when added in a twofold molar excess over Smt3p. Smt3p-tagged proteins show reduced electrophoretic mobility in the presence of twofold molar excess of VHHs, concomitant with the disappearance of free Smt3p. Right; SDS PAGE gels of the corresponding samples. (B) SDS PAGE of purified Smt3p and Smt3p-tagged proteins used for immunoblots are shown on the left. Immunoblots are displayed on the right as indicated. Immunoblots were performed with VHHs as the primary probes, followed by anti-HA monoclonal antibody to detect HA-tagged VHHs. (C) Only VHH1SMT3 is capable of detecting free Smt3p and its Smt3p-SBP-His6 tagged version by immunoblot. (D) VHH1SMT3 detects free Smt3p in mammalian whole cell lysates spiked with purified Smt3p.

We next performed immunoblotting against purified recombinant Smt3p-tagged proteins. All four nanobodies recognize Smt3p fused to Ube2G2 and GFP in immunoblot (Fig. 2B). Only VHH1SMT3 recognizes untagged Smt3p and Smt3p-SBP-His6 (Fig. 2B,C). This suggests that VHH1SMT3 may recognize a partially folded 3D epitope that persists under reducing SDS-PAGE conditions. Smt3p migrates at a higher apparent molecular weight on SDS-PAGE than calculated (11 kDa vs ~ 15 kDa), indicating incomplete unfolding in this denaturing environment24.

The specificity of VHH1SMT3 is further shown in Fig. 2D, where it detects a small amount of Smt3p added to a whole cell lysate from mammalian cells. We saw no evidence of any cross-reaction with mammalian proteins, consistent also with the modest degree of sequence similarity between yeast and mammalian SUMO proteins (see below, Fig. 6).

NMR spectroscopy reveals C-terminal binding of anti-Smt3p nanobodies

All four nanobodies bind to both Smt3p-tagged proteins and Smt3p alone in solution (Fig. 2). We next determined their binding sites by NMR. To identify the perturbed residues in Smt3p upon binding of a nanobody, we used 1H 15N-TROSY-HSQC spectroscopy on purified Smt3p protein in the presence and absence of a slight (110%) molar excess of VHH1SMT3, VHH2SMT3, and VHH4SMT3. Because of the high sequence similarity and identical CDR2 and CDR3 sequences between VHH2SMT3 and VHH3SMT3, we performed NMR analysis only with VHH2SMT3.

The Smt3p residues whose chemical shifts are perturbed upon binding of VHH1SMT3 are shown in Fig. 3A. Residues that show moderate changes in chemical shifts (> 0.1 ppm) are highlighted in yellow, while those showing more significant perturbations (> 0.2 ppm) are marked in red. The majority of significantly perturbed residues cluster near the C-terminus of Smt3p. VHH2SMT3 and VHH4SMT3 also bind near the C-terminus, albeit with fewer significantly affected residues compared to VHH1SMT3 (Fig. 3B,C). Given the sequence similarity of VHH2-4SMT3 (Fig. 1A), it is not surprising that the Smt3p residues affected by binding with VHH2SMT3 and VHH4SMT3 are very similar (Fig. 3D), corroborating the validity of this analysis. The distinct binding pattern of VHH1SMT3 compared to VHH2SMT3 and VHH4SMT3 (Fig. 3E) may explain its unique ability to recognize both free Smt3p and Smt3p-tagged proteins also in immunoblots.

Epitope mapping by 15N NMR shows that all VHHs bind near the C terminus of Smt3p. (A–C) 1H 15N-TROSY-HSQC spectrum of 15N-labeled Smt3p in the presence of excess VHH1SMT3 (red) (A), VHH2SMT3 (blue) (B), and VHH4SMT3 (pink) (C). The spectra are overlaid on those of Smt3p in the absence of added VHH (black). Individual Smt3p residues that show estimated lower limit for combined chemical shift changes in parts per million (ppm) upon VHH binding are shown in the middle panels. Residues with chemical shift changes with ppm > 0.1 are indicated in yellow, and those with ppm > 0.2 are indicated in red. Residues with > 0.1 ppm, yellow and red, mapped onto a surface rendering of Smt3p (PDB:1EUV) are shown on the right. (D) Comparison of 1H 15N-TROSY-HSQC spectrum (left) and estimated lower limit of combined chemical shift changes of Smt3p residues (right) in the presence of VHH2SMT3 (blue) overlaid on the spectrum obtained in the presence of VHH4SMT3 (pink) highlights the similarity of the presumptive contact residues. (E) Overlay of the spectra collected in the presence of VHH1SMT3 (red) and VHH2SMT3 (blue) showcases the differences in residues affected by their respective VHH binding. The inclusion of VHH1SMT3 shows stronger perturbation towards the C-terminus of Smt3p consistent with a distinct mode of binding. Note that the Kd values for VHH1SMT3 and VHH2SMT3 are similar (Table 1).

Differential inhibition of Ulp1p-mediated Smt3p cleavage by anti- Smt3p nanobodies

Smt3p-tagged proteins are substrates for Ulp1p, a SUMO protease, which targets the terminal glycine of Smt3p for ‘scarless’ removal of the tag22,24. The crystal structure of the Ulp1p- Smt3p complex25 (PDB: 1EUV) shows that Ulp1p engages the C-terminus of SUMO, with a groove positioning the terminal Gly-Gly residues for cleavage (Fig. 4A,B). Given that VHH1SMT3–VHH4SMT3 bind near the C-terminus of Smt3p, we investigated their impact on Ulp1p-mediated cleavage of Smt3p-tagged proteins. We focused on VHH1SMT3 and VHH2SMT3, the latter serving as a representative for VHH2-4SMT3 because of their similar CDR sequences, binding properties, and perturbation of NMR spectra.

VHH1SMT3 and VHH2SMT3 inhibit cleavage of Smt3p-tagged proteins by Ulp1p. (A,B) X-ray crystal structure (PDB: 1EUV) of SUMO protease (Ulp1p) in complex with Smt3p. Residues perturbed upon binding of VHH1SMT3 (A) and VHH2SMT3 (B) as determined by NMR are indicated in the color code of Fig. 3. (C–E) Cleavage of Smt3p-tagged proteins by Ulp1p in the presence and absence of a twofold molar excess of VHH over Smt3p at the indicated time points for: Smt3p-SBP-His6 (C), His6- Smt3p-Ube2G2 (D), and Smt3p-GFP-SBP-His6 (E). Quantification of cleavage, based on 3 independent experiments, is shown on the left. A representative SDS PAGE gel of the reaction is shown on the right. Major protein species are identified to the right. (F) Overlay of plots shown in (C–E) highlight the distinction in amount of cleaved product for the indicated substrates.

In the presence of VHH1SMT3, all of the Smt3p-tagged fusion proteins tested are resistant to cleavage by Ulp1p (Fig. 4C–F). In contrast, VHH2SMT3 only partially inhibits cleavage by Ulp1p. The extent of inhibition of cleavage by VHH2SMT3 varies for the different Smt3p-tagged proteins. The identity of the fusion partner thus contributes to accessibility of the Ulp1p cleavage site. These findings indicate that the nanobodies, particularly VHH1SMT3, interfere with Ulp1p’s access to its cleavage site on Smt3p, either because their binding regions overlap, or because of conformational changes induced in Smt3p that reduce Ulp1 recognition.

Immobilized VHH2SMT3 enables purification of Smt3p-tagged protein

Leveraging the fact that VHH2SMT3-bound Smt3p-tagged proteins remain susceptible to cleavage by Ulp1p, we devised a purification strategy for Smt3p-tagged proteins by immobilizing VHH2SMT3 on CNBr-activated Sepharose beads to create an affinity resin (Fig. 5A). We used this resin to purify two Smt3p-tagged fusion proteins: His6- Smt3p-Ube2G2 and Smt3p-GFP-SBP-His6. The VHH2SMT3-Sepharose resin performs comparably to Ni–NTA columns, with the added advantage of allowing on-column SUMO tag cleavage by Ulp1p in the presence of reducing agents like DTT (Fig. 5B). This approach streamlines purification of SUMO-tagged proteins as an efficient alternative to more conventional methods for obtaining tag-free target proteins.

VHH2SMT3 can be conjugated to a solid support for retrieval of Smt3p-tagged proteins from bacterial extracts. (A) Workflow showing purification done using a Ni–NTA agarose column and VHH2SMT3 conjugated Sepharose beads. (B) SDS PAGE gel showing different stages of purification of His6-Smt3p-Ube2G2 (top) and Smt3p-GFP-SBP-His6 (bottom). Lys: Lysate, FT: Flow through, WT: Wash through, El: Elution.

Smt3p and Smt3pCTD tagging: nanobody-mediated protein retrieval in mammalian systems

The human genome encodes multiple homologs of the yeast SUMO protein: SUMO1, SUMO2, SUMO3, SUMO4, and SUMO5. Among these, SUMO1, SUMO2, and SUMO3 are widely expressed. Yeast and human SUMO proteins show only moderate sequence similarity (Fig. 6A), with human SUMO1 and SUMO2 sharing approximately 48.5% and 44.6% sequence identity with yeast SMT3, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3). Despite this relatively low degree of sequence similarity, the three-dimensional structures of Smt3p and human SUMO proteins are highly homologous, all adopting a ubiquitin-like fold29.

Smt3p VHHs do not cross react with human SUMO proteins but retrieve Smt3p and Smt3pCTD-tagged GFP from HEK 293T transfectants. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of yeast SUMO (SMT3) and human SUMO variants 1–5 (hSUMO1-5). (B) Native PAGE of VHHs added to human SUMO1 in a threefold molar excess over SUMO1. The migration of hSUMO1 is not affected upon inclusion of the nanobodies. The absence of an additional species that could correspond to a complex indicates the absence of binding. The corresponding SDS PAGE gel is shown below the native PAGE gel. (C) Native PAGE of hSUMO2 showing absence of binding towards Smt3p VHHs similar to (B). (D) VHH1SMT3 fails to recognize human SUMO1 and human SUMO2 in immunoblot. (E) Expression of Smt3p-GFP or GFP tagged with the C terminal region of Smt3p (Smt3pCTD-GFP) in HEK 293T transfectants. SDS PAGE gel of whole cell lysate is shown on the top and the corresponding immunoblots performed with anti-GFP monoclonal antibody and with anti-β actin monoclonal antibody are shown below. (F) Anti-GFP and anti-HA tag immunoblots after retrieval by VHH1SMT3 and VHH2SMT3 of Smt3p tagged GFP from HEK 293T cells. Anti-HA tag indicates the nanobody used for retrieval.

We examined the specificity of the Smt3p-specific nanobodies using native PAGE and immunoblotting. None of the Smt3p-specific nanobodies cross-react with human SUMO1 or human SUMO2 proteins (Fig. 6B–D). Given the high sequence identity (96.8%) between SUMO2 and SUMO3 (Supplementary Fig. 3), we predict that the nanobody is unlikely to cross-react with SUMO3 either.

The high specificity of VHH1-4SMT3 for yeast Smt3p opens up opportunities for using these nanobodies in mammalian systems. We expressed full-length Smt3p-tagged GFP and a construct featuring only the C-terminal region of Smt3p (Smt3pCTD: R55-G98) fused to GFP in mammalian cells. We designed the CTD construct based on previous reports indicating that full-length SUMO tags expressed in mammalian systems are susceptible to cleavage by endogenous deSUMOylases30. Our selection of the R55-G98 region for the CTD construct was guided by NMR data showing residues beyond R55 being significantly perturbed by VHH1,2SMT3 binding.

Both proteins were retrieved using VHH1SMT3 and VHH2SMT3 (Fig. 6E,F). The Smt3p tag, in conjunction with VHH1-4SMT3, provides a versatile tool for expression and isolation of tagged proteins in mammalian cells. This combination expands the utility of yeast SUMO tags beyond bacterial expression systems and offers new possibilities to study protein interactions and modifications in mammalian systems.

Cytoplasmic expression of Smt3p-specific nanobodies in yeast affect cell growth

We expressed VHH1-4SMT3 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain EBY100 to investigate their impact on yeast growth. Using the copper-inducible CUP1 promoter, we first overexpressed 7xHis-tagged Smt3p and confirmed its presence by immunoblotting with VHH1SMT3 (Fig. 7A). We then expressed HA-tagged VHH1SMT3 and VHH2SMT3, including variants of VHH1SMT3 with nuclear localization signals (NLS) at either terminus, with or without a GFP fusion for visualization (Fig. 7B,C). Immunoblot analysis showed that expression levels were modulated in response to increasing concentrations of CuSO4.

Cytosolically expressed VHH1SMT3 and VHH2SMT3 compromise yeast growth. (A) Smt3p overexpressed under the control of the CUP1 promoter in EBY100 yeast is readily detected by VHH1SMT3. Left: whole cell lysate of EBY100 yeast transformed with His7-Smt3p plasmid, as indicated. Shown is an immunoblot of overexpressed His7- Smt3p upon induction with 100 µM CuSO4 detected by anti-His antibody (middle) and VHH1SMT3 (right). (B) Anti-HA tag immunoblot to detect expression of VHH1SMT3, VHH2SMT3 and VHH1SMT3 equipped with a C terminal nuclear localization tag (NLS), induced in response to varying concentrations (0, 100, 300 µM) of CuSO4. (C) Anti-HA tag immunoblot of GFP- and NLS-tagged versions of VHH1SMT3 in yeast. (D) Yeast spot dilution growth assay with the VHH constructs shown in (B,C) on CuSO4-containing (0, 100, 300 µM) yeast synthetic media agar plates. The four constructs showing a significant growth defect with increasing concentration of CuSO4 are shown on the right. (E) Fluorescence microscopy showing EBY100 yeast cells expressing VHH1SMT3-GFP tagged versions with and without an NLS. Images for phase-contrast (left), the GFP channel (middle) and an overlay of both (right) are shown. Notice increased nuclear localization of VHH1SMT3 with an NLS tag, regardless of whether the NLS is located at the N or C terminus.

To assess the impact of induced expression of VHH1-4SMT3 on yeast growth, we performed spot dilution assays at increasing CuSO4 concentrations (Fig. 7D). While overexpression of VHH2SMT3 showed no significant growth defects, VHH1SMT3 constructs impaired growth (300 μM CuSO4), particularly when fused with GFP or NLS. Microscopy confirmed the expression and localization of GFP-labeled VHH1SMT3, showing both cytoplasmic and nuclear distribution (Fig. 7E). We saw heterogeneous GFP labeling across the yeast population, likely due to variable plasmid copy numbers resulting from the use of plasmids with the 2μ origin of replication31. VHH2SMT3 showed higher expression levels than VHH1SMT3, with some leaky expression even in the absence of CuSO4, yet it imposed no observable growth defects (Fig. 7B,D). This may be due to the lower inhibition of Ulp1p cleavage caused by VHH2SMT3 or a lesser impact on SUMOylation events mediated by E1, E2, and E3 ligases. These possibilities will require further study.

For VHH1SMT3, expression was detected in the presence of 100 μM CuSO4 (Fig. 7B). N-terminally GFP tagged VHH1SMT3 showed enhanced expression compared to the C terminal tag (Fig. 7B,D). Impaired growth was seen with increasing CuSO4 concentrations for most VHH1SMT3 constructs equipped with NLS and GFP tags, except for 'NLS-GFP-VHH1SMT3-HA’ (Fig. 7D, bottommost left). The variability in growth effects may be attributed to non-uniform expression of VHH1SMT3 across the cultures, as observed microscopically (Fig. 7B), or differences caused by the relative orientation of GFP in the protein fusions.

In conclusion, we have shown that overexpression of an Smt3p-specific nanobody, particularly VHH1SMT3, impairs yeast growth. We attribute such impairment to inhibition of SUMOylation (or de-SUMOylation). The use of Smt3p-specific nanobodies offers a novel method to study SUMOylation in yeast without having to genetically manipulate SMT3 or related genes.

Discussion

We have characterized four nanobodies that are specific for the yeast SUMO protein, Smt3p. These nanobodies are versatile biochemical tools for diverse applications in bacterial, yeast and mammalian systems. VHH1-4SMT3 complement and extend current purification methods and show excellent performance in immunoblotting. Perhaps more relevant from a biological perspective, these nanobodies induce growth defects when expressed in yeast, as evidence of their impact on Smt3p function. This property opens up new avenues for the study of SUMOylation in yeast, with minimal perturbation of other cellular proteins.

The relationships among the identified nanobodies provide some insights into their origins. CDRs are the variable regions on nanobodies that bind to target epitopes. VHH2-4SMT3 are quite similar, sharing an identical CDR3 sequence with only minor substitutions in their germline-encoded segments. This high degree of similarity suggests a common origin, presumably from the same germline B cell, with the observed substitutions likely arising from somatic hypermutation.

The ability of all four nanobodies to recognize Smt3p-tagged proteins in immunoblot and in their native folded state suggests recognition of an epitope that resists denaturation under reducing SDS-PAGE conditions. We were unable to identify a short linear peptide within the segment R64–E90 recognized by these nanobodies. However, the successful retrieval of the C-terminal region of Smt3p (Smt3pCTD, R55-G98) by both VHH1SMT3 and VHH2SMT3 expressed in mammalian cells shows that the epitope likely encompasses a larger region near the C-terminus.

The SUMO protease Ulp1p binds near the C-terminus of Smt3p and cleaves after the terminal Gly-Gly residues12,22,25. In addition to de-SUMOylation of substrates, Ulp1p also cleaves Smt3p for maturation, making it crucial for yeast viability12. VHH1SMT3 and VHH2SMT3 interact with the Ulp1p bound region on Smt3p differently, leading to differences in inhibition of Ulp1p activity. VHH1SMT3 causes significant chemical shifts in multiple C-terminal residues of Smt3p (Y67, G69, I70, L81, M83, D87, E90). Several of these residues overlap partially or completely with the buried contact residues between Smt3p and Ulp1p (PDB: 1EUV, Figs. 3, 4A). This extensive overlap likely explains the complete inhibition of Ulp1p-mediated cleavage of Smt3p-tagged proteins in the presence of VHH1SMT3. In contrast, notwithstanding similar Kd values, VHH2SMT3 interacts with fewer residues (D68, G69, T77, L81) as shown by NMR. Only G69 and T77 are shared with the VHH1SMT3 binding sites, with the major differences in binding apparent at residues D68 and L81. While VHH1SMT3 completely blocks cleavage by Ulp1p, VHH2SMT3 is more permissive. The observation of differential cleavage rates across various substrates in the presence of VHH2SMT3 (Fig. 4) suggests, perhaps not surprisingly, that different SUMOylated proteins in yeast will undergo de-SUMOylation at different rates. This phenomenon, difficult to capture with traditional methods, opens up new avenues to investigate the kinetics and specificity of SUMO processing in vivo.

The strict specificity of VHH1-4SMT3 for yeast Smt3p enables their use in mammalian systems without interference from endogenous SUMO proteins. We used this approach by expressing Smt3p and Smt3pCTD-tagged GFP in HEK 293T cells and retrieved them using VHH1,2SMT3 from mammalian cell lysates.

The study of SUMOylation has been challenging due to the low abundance of Smt3p and the dynamic nature of SUMOylation in response to various stressors2,3,13,14,15. Our approach involves the expression of VHH1SMT3 and VHH2SMT3 nanobodies in yeast. Expression of VHH1SMT3 impairs growth, especially when targeted to the nucleus by means of an NLS (Fig. 7E). The growth defect is enhanced when VHH1SMT3 is fused with GFP, possibly due to increased protein stability, increased expression levels conferred by the GFP tag, or enhanced disruption of SUMOYlation process caused by the larger protein fusion. Since Smt3p cleavage by Ulp1p is necessary to form mature Smt3p12, VHH1SMT3’s growth inhibition could be attributed to a failure to form mature Smt3p in cells.

SUMOylation in yeast predominantly targets nuclear proteins involved in diverse cellular processes including transcriptional regulation, nucleolar dynamics, and DNA synthesis and repair mechanisms13,18,32. However, several cytoplasmic proteins are also SUMOylated, such as septins (cytoskeletal proteins essential for bud neck formation during mitosis)33, oxidative stress response proteins (including Sod1 and Tsa1)18, and various translation and metabolism-related proteins18. Our observation of growth defects following cytoplasmic expression of GFP-conjugated VHH1SMT3 suggests potential perturbation of these cytoplasmic SUMOylated proteins, though further investigation is needed to identify the specific targets affected.

Identification and characterization of SUMOylated proteins in yeast presents technical challenges because SUMOylation is dynamic and reversible14,17,18,19,34. Oxidative stress, heat shock, or DNA damage can all increase the fraction of SUMOylated proteins17,18,19,34. Similarly, mutations that affect SUMO cleavage (ulp2Δ), or SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases that target SUMOylated proteins for degradation (slx5Δ, uls1Δ) increase the level of SUMO conjugates19. We have not pursued these strategies to increase the amount of SUMOylated proteins. SUMOylated proteins in wild-type EBY100 yeast were scarce and failed to produce a compelling signal in immunoblots, a limitation for biochemical analysis17,18,19,34.

A nanobody-based method has several advantages for studying yeast SUMOylation. It provides an alternative to genetic manipulation of Smt3p, allows for the capture of SUMOylated intermediates that are protected from Ulp1-mediated cleavage, and enables the study of SUMOylation dynamics without completely abolishing Smt3p function. Further investigation is needed to fully understand the effects of these nanobodies on yeast SUMOylation. Of particular interest is how they interact with the E1, E2, E3 enzyme SUMOylation cascade. In conclusion, nanobody-based approaches offer a promising new tool that may help unravel the complexities of yeast SUMOylation.

Materials and methods

Preparation of phage display nanobody library and screening

Methods for preparation of the phage display library was followed as described in35, briefly described below.

Immunization and RNA extraction

An alpaca was immunized with purified recombinant His6- Smt3p-Ube2G2 protein (100 μg per injection) for four rounds at biweekly intervals. One week after the final immunization, alpaca blood was collected and PBMCs were isolated on a Ficoll-Paque PLUS gradient (Cytiva, 17,144,002). Total RNA was then extracted from the PBMCs using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, 74,104).

cDNA synthesis and VHH amplification

cDNAs were synthesized using Superscript III First Strand Synthesis System (Thermo Fisher, 18,080,051). VHHs were then amplified from the cDNAs and cloned into a phagemid vector via restriction digestion and ligation. The resulting phagemid nanobody library was transformed into TG1 E. coli (Agilent, 200,123) cells by electroporation.

Phage display library generation

TG1 library cells were infected with helper phage M13KO7 (NEB, N0315S) at a 1:100 ratio (cells:phage) and cultured overnight at 30 °C, 220 rpm in 2YT media supplemented with Ampicillin (100 μg/mL) and Kanamycin (50 μg/mL). Phages were harvested by centrifugation and PEG/NaCl precipitation. The culture was centrifuged at 5000 × g for 10 min, and phages in the supernatant were precipitated using 1/6 volume of 2.5 M NaCl, 20% PEG 6000 (w/v) on ice for 1 h. Precipitated phages were collected by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 20 min, 4 °C) and resuspended in TBS (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl). The precipitation was repeated to reduce bacterial contamination.

Phage display screening

His6- Smt3p-Ube2G2 protein was biotinylated using ChromaLINK® Biotin Protein Labeling Kit (Vector laboratories, B-9007-105K) and immobilized on Dynabeads™ MyOne™ Streptavidin T1 magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher, 65,601). Purified phages were pre-cleared against 100 μL of unbound beads for 30 min. Pre-cleared phages were then incubated with 100 μL streptavidin magnetic beads containing 20 μg biotinylated protein for 1 h at RT. The beads were washed four times with TBST (TBS + 0.1% Tween 20). Bound phage were eluted with 500 μL of 0.2 M Glycine pH 2.2 for 10 min, then neutralized with 75 μL of 1 M Tris–HCl pH 9.1. Eluted phages were used to infect log-phase E. coli ER2738 (NEB, E4104) to generate the 'first round library’. A second round of screening was performed similarly using the 'first round library’ with 2 μg protein on beads.

ELISA and nanobody selection

An ELISA was performed with His6-SUMO-Ube2G2 immobilized on plates. Analysis of the hits led to the identification of four nanobody sequences reported in this study.

Nanobody expression for ELISA

Single colonies from the second-round library were grown in 4 × 96-well plates containing 2YT media. Cultures were incubated until the average OD600 per well reached 0.4–0.8. Protein expression was induced by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 1 mM, followed by overnight incubation at 30 °C with shaking at 220 rpm. After incubation, plates were centrifuged at 3000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected for ELISA.

ELISA procedure

Polystyrene high-bind microplates (Corning, 9018) were coated with 100 μL of His6- Smt3p-Ube2G2 at 1 μg/mL in PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4). The following day, wells were blocked with 200 μL of blocking solution (5% BSA in PBST; PBS + 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h at RT. After blocking, wells were washed three times with PBST. A 1:1 mixture of blocking solution and supernatant from IPTG-induced colonies was added to each well and incubated for 1 h at RT with rotation. Wells were then washed three times with PBST. Anti-E tag polyclonal HRP antibody (Invitrogen, PA1-21,895) was diluted 1:10,000, and 100 μL was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 1 h at RT with rotation, followed by three washes with PBST. The signal was developed by adding 100 μL of TMB substrate (Sigma, T4319) per well. The reaction was monitored until a significant blue color developed, taking care to assess the signal relative to background. The reaction was then quenched with 100 μL of 1M HCl per well. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a SpectraMax iD3 plate reader.

Nanobody sequences

VHH1SMT3 (GenBank accession number PQ875189):

QVQLVESGGGLVQPGGSLKLSCAASGFTFSDRVMSWVRQVPGKDLEWVSHITRRGSTTEYAD

FVKGRFSISRDNAKNMLYLQMNSLKPEDTAVYYCARGGQYSIDWAERGQGTQVTVSS

VHH2SMT3 (GenBank accession number PQ875190):

QVQLVETGGGLVQPGDSLTLSCVASGFVFSDSVITWVRQAPGKGPEWVAIIGYTGKAKSYAKSV

KGRFKIDRDNGMNTATLQMNNLTPDDTALYYCVRGDVPNGDGLERGQGTQVTVSS

VHH3SMT3 (GenBank accession number PQ875191):

QVQLVETGGGLVQPGGSLTLSCVASGFTFSDSVITWVRQAPGKGPEWVAIIGYTGKAKSYAKSV

KGRFKIDRDNGMNTATLQMNNLTPDDTALYYCVRGDVPNGDGLERGQGTQVTVSS

VHH4SMT3 (GenBank accession number PQ875192):

QLQLVETGGGLVQPGGSLRLSCVASGFAFSDSVITWVRQAPGKGPEWVAIIGYTGKARSYANS

VKGRFTIDRDNDKNTVYLQMNNLTPDDTALYYCVRGDVPNGDGLERGQGTQVTVSS

Nanobody and protein purification

Expression vectors and bacterial strains

Cytoplasmic proteins were expressed in BL21 (DE3) cells using the following plasmid vectors: (1) pET SUMO vector and modified pET SUMO vectors: His6- Smt3p-Ube2G2 (smt3p: Uniprot ID Q12306, Ube2G2: Uniprot ID P60604 ), Smt3p-GFP-SBP-His6, Smt3p-Sortag motif (LPETG)-SBP-His6 (SBP: Streptavidin binding protein tag), (2) pET 28 vector: Sortase A 5M (Addgene: 51,140), human SUMO1 (Boston Biochem, UL-712), His6-human SUMO2 (Uniprot ID P61956). Nanobodies were expressed using the pHEN6 vector with a PelB leader sequence followed by the nanobody sequence-HA tag-His6 tag in WK6 E. coli.

Cytoplasmic protein expression and purification

BL21 (DE3) cells were grown at 37 °C, 220 rpm in Terrific Broth (TB, RPI, T15000) until OD600 reached 0.4–0.8. Protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG, and cultures were grown for 5 h at 30 °C, 220 rpm. Cells were lysed using an Avastin Emulsiflex C3 homogenizer in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, cOmplete™ EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablet (Sigma, 11,873,580,001), DNAse I (Sigma, 10,104,159,001)) with three passes. Lysates were centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C using a JA20 rotor on a Beckman Coulter JE centrifuge. Clarified lysates were purified on Ni–NTA beads (Qiagen, 30,210), washed with TBS containing 10 mM Imidazole, and eluted in TBS with 250 mM Imidazole. To obtain His6- Smt3p, His6- Smt3p-Ube2G2 was cleaved using SUMO protease (Sigma, SAE0067) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The cleavage product was passed through Ni–NTA to capture His6- Smt3p. Untagged Smt3p was obtained by Thrombin (Cytiva, 27,084,601) cleavage to remove the His6 tag, followed by size exclusion chromatography (SEC).

Nanobody expression and purification

WK6 E. coli expressing nanobodies were grown in TB to OD600 0.8–1 at 37 °C, 220 rpm, induced with 1 mM IPTG, and grown overnight at 30 °C. Cells were pelleted at 5000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in 40 mL of TES buffer (0.2 M Tris pH 8.0, 0.5 M sucrose, 0.65 mM EDTA) per liter and incubated for 1 h on ice. Osmotic shock was used to lyse cells by adding 160 mL ice-cold water and incubating on ice for 30 min to release the periplasmic fraction. Cells were pelleted at 5000 × g for 20 min, and the supernatant containing VHH was purified using Ni–NTA affinity chromatography and SEC.

Protein concentrations were determined using NanoDrop One (Thermo Scientific, ND-ONE-W), with corrections for extinction coefficients.

SEC binding experiments

Equimolar ratios of VHH:His6- Smt3p at 100 μM concentration in 250 μL TBS were mixed and incubated at RT for 20 min. 200 μL of the mixture was applied to a Superdex 75 10/300 column (Cytiva, 17,517,401) at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min, collecting 0.5 mL elution fractions. Samples were analyzed on reducing 13% SDS-PAGE and 10% Native PAGE.

Native PAGE

10% native PAGE gels were prepared using Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide (30%/0.8% w/v), 0.375 M Tris–HCl (pH 8.8), 10% (w/v) ammonium persulfate, and TEMED. The running buffer contained 25 mM Tris and 192 mM Glycine. The 2 × sample buffer consisted of 62.5 mM Tris HCl pH 6.8, 25% glycerol, and 1% bromophenol blue. Gels were run at 120V at 4 °C for 1.5 h.

For native gel shift binding assays, a twofold molar excess of VHH over Smt3p or Smt3p-tagged variants was added and incubated in TBS for 20 min at RT, followed by the addition of sample buffer. Samples were run immediately and stained with InstantBlue® Coomassie Protein Stain (Abcam, ab119211).

Microscale thermophoresis (MST)

Smt3p was C-terminally tagged with Alexa Fluor 647 (AF647) using Sortase A 5M mediated conjugation. The reaction mixture contained: 2.5 μM Sortase A 5M, 50 μM Smt3p-Sortag motif (LPETG)-SBP-His6, 500 μM Gly3-AF647 in TBS. The mixture was incubated for 30 min at RT. Unreacted components and Sortase A 5M were removed using Ni–NTA agarose resin. The flowthrough was concentrated and further purified by size exclusion chromatography (SEC).

MST measurements were performed using a Monolith NT.115pico Instrument (Nano Temper) at the Center for Macromolecular Interactions, Harvard Medical School. Binding experiments were conducted in triplicate, and data fitting was performed using MO Affinity Analysis software to determine binding affinity (Kd).

Gly3-AF647 was synthesized by conjugating AF647 (Alexa Fluor™ 647 C2 Maleimide, Thermo Fisher, A20347) to Gly3 peptide via thio-Michael addition. The product was purified using reverse-phase HPLC and confirmed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (Waters UPLC-MS Acquity).

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed on proteins transferred to PVDF membranes after separation by SDS PAGE. For immunoblotting with VHH, first the membranes were blocked with blocking buffer; 5% BSA in TBST (20 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20), for 1 h at RT. Then, VHHs were added at 2 μg/mL in blocking buffer for 1 h at RT. The membrane was then washed in TBST thrice and an anti-HA-HRP monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen, 26,183-HRP) was added at 1:10,000 dilution and incubated for 30 min at RT. Following this, the membrane was washed thrice in TBST and the signal was developed using Pierce™ ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Thermo Fisher, 32,106) and membranes were imaged using ChemiDoc MP (Biorad, 12,003,154).

Immunoblotting for other cell lysate samples were performed similarly with antibodies conjugated with HRP: Anti-GFP monoclonal HRP (Abclonal AE030) used at 1:2000 dilution in blocking buffer, β-actin monoclonal antibody HRP (Abclonal, AC028) used at 1:2000 dilution in blocking buffer, and anti-HA tag monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen, 26,183-HRP) at 1:10,000 dilution.

NMR analysis of binding epitope

15N-labeled Smt3p was produced by expressing His6- Smt3p-Ube2G2 in M9 minimal media containing 15NH4Cl. Cells were grown at 37 °C, 220 rpm until OD600 reached 0.5, then induced with 1 mM IPTG and grown at 30 °C, 220 rpm for 20 h. Untagged Smt3p was obtained by cleavage with Thrombin and Ulp1. NMR experiments were performed using 0.5 mM 15N-labeled SMT3, 110% molar equivalent of VHHs (when present), 10% D2O in NMR buffer (50 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl). 15N-TROSY HSQC data were collected at 25 °C on a Bruker Advance II 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a Prodigy cryogenic probe. Data was processed using nmrPipe, and analysis and plots were generated using CARA software. Combined chemical shift changes were calculated using the equation: sqrt((ΔHcs)^2 + (ΔNcs/5.0)^2). NMR assignments for unbound Smt3p protein were obtained from a previous publication29.

PDB images were rendered using Chimera X 1.2.4 software.

Ulp1p (SUMO protease) cleavage experiments

Reaction mixtures contained Smt3p-tagged proteins at 1 mg/mL in 100 μL TBS and a twofold molar excess of VHH1SMT3 or VHH2SMT3 (when present). Mixtures were incubated at RT for 20 min before adding 1 μL of Ulp1 (Sigma, SAE0067, reconstituted based on manufacturer’s instructions). Reactions proceeded at 25 °C with mild shaking at 300 rpm. Aliquots were taken at indicated time points and quenched by adding 5 × Laemmli buffer (350 mM Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 30% glycerol, 10% w/v SDS, 600 mM DTT, 0.01% w/v bromophenol blue) and boiling at 95 °C for 5 min. Samples were analyzed on 13% SDS-PAGE gels and stained with InstantBlue Coomassie dye.

Experiments were performed in triplicate and SDS-PAGE images were quantified using ImageJ software and plotted using GraphPad Prism 8.

VHH2SMT3 conjugated sepharose beads preparation

CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B beads (Cytiva, 17043001) were used to conjugate VHH2SMT3 following the manufacturer’s instructions. Lyophilized beads were washed with 1 mM HCl to remove additives, then equilibrated with coupling buffer (0.1 M NaHCO3, pH 8.3, 0.5 M NaCl). VHH2SMT3 was buffer-exchanged to coupling buffer using SEC. Activated beads were incubated with VHH2SMT3 for 2 h at RT with gentle rotation. Excess ligand was washed away with 5 column volumes of coupling buffer. Remaining active groups were blocked using 0.1 M Tris–HCl buffer pH 8.0 for 2 h. Beads were washed with 3 cycles of alternating pH buffers (5 column volumes each): low pH (0.1 M Acetic acid/sodium acetate pH 4.0, 0.5 M NaCl) and high pH (0.1 M Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.5 M NaCl). The column was stored in TBS until further use. Three trials of column preparation yielded an average binding capacity of 4.8 mg VHH2SMT3 per mL of resin, suggesting an expected binding capacity of ~ 4.8 mg/mL for Smt3p-tagged proteins.

Protein purification using VHH2SMT3 sepharose column

Protein pellets of His6- Smt3p-Ube2G2 and Smt3p-GFP-SBP-His6 were lysed as described in the ‘protein purification’ section. The lysate was split in half: one half was purified using Ni–NTA beads as previously described, while the other half was passed through the VHH2SMT3 Sepharose column. After collecting the flowthrough, the beads were washed with TBS until protein elution ceased (monitored qualitatively using Bradford reagent). The resin in TBS was supplemented with 2 mM DTT, and Ulp1p was added. The mixture was incubated at RT for 3 h with rotation. After cleavage, the flowthrough was collected and designated as ‘Eluate’ for the protein of interest.

Multiple sequence alignment and pairwise alignments of yeast SMT3 and human SUMO proteins

Jalview software 2.11.4.0's "Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0"36 was used for multiple sequence alignment with default settings. The final output utilized in-built default ‘Clustal X’ coloring scheme. Pairwise sequence alignments were done using EMBOSS Water Smith-Waterman algorithm37.

Mammalian cell expression and VHH mediated retrieval

HEK 293T (ATCC: CRL-3216) and HeLa (ATCC: CRM-CCL-2) cells were cultured in DMEM high glucose (Gibco, 11965092) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1 × Penicillin–Streptomycin (Gibco, 15140122). The plasmid vector pCMV-GFP (Addgene: 11153) was modified to incorporate Smt3p and C-terminal region of Smt3p (Smt3pCTD R55-G98) at the N-terminus using Takara In-Fusion cloning.

HEK 293T cells were grown to 80% confluency in 60 mm plates (Corning, 430166) and transfected using TransIT-LT1 reagent (Mirus, MIR 2304) following manufacturer’s instructions. 24 h post-transfection, cells were collected, washed with PBS, and pelleted at 800 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Cells were lysed using lysis buffer: Tris HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40 substitute, 1 mM MgCl2, cOmplete™ EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablet (Sigma, 11873580001). Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Lysate concentrations were determined using Bradford reagent with a BSA standard curve (Thermo Scientific, 23210).

For the VHH retrieval assay, 1 mg of lysate was added per sample to 20 μL anti-HA magnetic beads (Sigma, SAE0197) containing 50 μg of HA-tagged VHH1SMT3 or VHH2SMT3. Samples were incubated for 1 h at 4 °C with rotation. Beads were washed thrice with 0.1% TBST. Proteins were eluted by adding 50 μL of 1 × Laemmli buffer directly to the beads and boiling at 95 °C. 20 μL volumes per sample were loaded on a 13% SDS-PAGE gel followed by immunoblotting.

Yeast-related methods

Yeast strains and plasmids

Saccharomyces cerevisiae EBY100 strain was used for all experiments. The Yep181-CUP1-His- Smt3p plasmid (Addgene: 99,536) served as the base for all constructs. VHH sequences were cloned by replacing His6-Smt3p using Takara In-Fusion cloning (Takara, 638,946). The NLS tag used in this study had the sequence KRPAATKKAGQAKKKK.

Yeast transformation and growth

Yeast cells were grown in YPD media (RPI: Y20090) and transformed using the Frozen-EZ Yeast Transformation II kit (Zymo, T2001) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Post-transformation, yeast was plated on yeast synthetic drop-out media plates without Leucine, composed of 1.6 g/L Yeast Synthetic Drop-out Medium Supplements without Leucine (Sigma, Y1376), 6.7 g/L Yeast nitrogen base without amino acids (Sigma, Y0626), and 20 g/L bacteriological agar (A5306).

For CuSO4-containing plates, the indicated concentrations of CuSO4 (100 or 300 μM) were added to autoclaved yeast synthetic dropout media agar solution after cooling to approximately 55 °C, before pouring into plates for solidification. For liquid culture propagation, synthetic media without Leucine was used to grow EBY100 yeast until OD600 reached 1, at which point induction was initiated by supplementing the media with the indicated concentrations of CuSO4.

Yeast cell lysis and western blot

Yeast cells at 1.0 OD600 were induced with indicated CuSO4 concentrations and grown overnight in 14 mL culture tubes (VWR, 47,729–576) with 5 mL media at 30 °C, 250 rpm. Cells were pelleted at 3000 × g for 5 min and lysed using CelLytic™ Y Cell Lysis Reagent (Sigma, C4482) supplemented with Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablet, based on wet weight following the manufacturer’s instructions. Lysis proceeded for 30 min at RT on a rotator, followed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 10 min to pellet cellular debris. The protein-containing supernatant was collected, mixed with Laemmli buffer, and boiled at 95 °C for 5 min before loading equal volumes on a 13% SDS-PAGE gel. The gel was then transferred to a PVDF membrane using the Trans-Blot turbo transfer system (Biorad, 1,704,150). Immunoblots were performed as described above.

Yeast spot dilution growth assay

Yeast constructs in synthetic media without leucine were grown to 5.0 OD600 in 2 mL cultures. The cells were diluted to 1.0 OD600 and tenfold serial dilutions were prepared starting from 1.0 OD600. 5 μL of each dilution was plated on synthetic media plates without leucine containing varying concentrations of CuSO4. Cells were grown at 30 °C for 3 days and imaged using ChemiDoc MP (Biorad, 12,003,154).

Microscopy

Yeast cells (from single colonies on agar plates) grown in synthetic media without leucine containing 300 μM CuSO4 were placed on glass slides and covered with a coverslip. Images were captured using a Keyence BZ-X800 microscope at 100 × magnification using the GFP channel and brightfield with phase contrast. Overlaid images were generated using Keyence’s inbuilt software.

Data availability

The SMT3-VHH nanobody protein sequences are provided within the manuscript and the nucleotide sequences are provided in the supplementary information. Nucleotide sequences from the current study have also been deposited in the GenBank repository with accession numbers: PQ875189, PQ875190, PQ875191, PQ875192. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucleotide/. All sequence information can be obtained from the corresponding author, Pavana Suresh, pavana.suresh@childrens.harvard.edu.

References

Meluh, P. B. & Koshland, D. Evidence that the MIF2 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes a centromere protein with homology to the mammalian centromere protein CENP-C. Mol. Biol. Cell. 6(7), 793–807. https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.6.7.793 (1995).

Celen, A. B. & Sahin, U. Sumoylation on its 25th anniversary: Mechanisms, pathology, and emerging concepts. FEBS J. 287(15), 3110–3140. https://doi.org/10.1111/febs.15319 (2020).

Vertegaal, A. C. O. Signalling mechanisms and cellular functions of SUMO. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 23(11), 715–731. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-022-00500-y (2022).

Jentsch, S. & Psakhye, I. Control of nuclear activities by substrate-selective and protein-group SUMOylation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 47, 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133453 (2013).

Psakhye, I. & Jentsch, S. Protein group modification and synergy in the SUMO pathway as exemplified in DNA repair. Cell 151(4), 807–820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.021 (2012).

Cremona, C. A. et al. Extensive DNA damage-induced sumoylation contributes to replication and repair and acts in addition to the mec1 checkpoint. Mol. Cell. 45(3), 422–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2011.11.028 (2012).

Rosonina, E., Duncan, S. M. & Manley, J. L. SUMO functions in constitutive transcription and during activation of inducible genes in yeast. Genes Dev. 24(12), 1242–1252. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.1917910 (2010).

Hooker, G. W. & Roeder, G. S. A Role for SUMO in meiotic chromosome synapsis. Curr. Biol. 16(12), 1238–1243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.045 (2006).

Li, S. J. & Hochstrasser, M. A new protease required for cell-cycle progression in yeast. Nature 398(6724), 246–251. https://doi.org/10.1038/18457 (1999).

Li, S. J. & Hochstrasser, M. The yeast ULP2 (SMT4) gene encodes a novel protease specific for the ubiquitin-like Smt3 protein. Mol. Cell Biol. 20(7), 2367–2377. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.20.7.2367-2377.2000 (2000).

Hickey, C. M., Wilson, N. R. & Hochstrasser, M. Function and regulation of SUMO proteases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13(12), 755–766. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm3478 (2012).

Li, S. J. & Hochstrasser, M. The Ulp1 SUMO isopeptidase: distinct domains required for viability, nuclear envelope localization, and substrate specificity. J. Cell Biol. 160(7), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.200212052 (2003).

Gutierrez-Morton, E. & Wang, Y. The role of SUMOylation in biomolecular condensate dynamics and protein localization. Cell Insight 3(6), 100199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellin.2024.100199 (2024).

Moallem, M. et al. Sumoylation is largely dispensable for normal growth but facilitates heat tolerance in yeast. Mol. Cell Biol. 43(1), 64–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/10985549.2023.2166320 (2023).

McNeil, J. B. et al. 1,10-phenanthroline inhibits sumoylation and reveals that yeast SUMO modifications are highly transient. EMBO Rep. 25(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44319-023-00010-8 (2024).

Dieckhoff, P., Bolte, M., Sancak, Y., Braus, G. H. & Irniger, S. Smt3/SUMO and Ubc9 are required for efficient APC/C-mediated proteolysis in budding yeast. Mol. Microbiol. 51(5), 1375–1387. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03910.x (2004).

Ulrich, H. D. & Davies, A. A. In vivo detection and characterization of sumoylation targets in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Mol. Biol. 497, 81–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-59745-566-4_6 (2009).

Zhou, W., Ryan, J. J. & Zhou, H. Global analyses of sumoylated proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Induction of protein sumoylation by cellular stresses. J. Biol. Chem. 279(31), 32262–32268. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M404173200 (2004).

Pabst, S., Doring, L. M., Petreska, N. & Dohmen, R. J. Methods to study SUMO dynamics in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 618, 187–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.mie.2018.12.026 (2019).

Marblestone, J. G. et al. Comparison of SUMO fusion technology with traditional gene fusion systems: enhanced expression and solubility with SUMO. Protein Sci. 15(1), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1110/ps.051812706 (2006).

Peroutka, R. J., Elshourbagy, N., Piech, T. & Butt, T. R. Enhanced protein expression in mammalian cells using engineered SUMO fusions: secreted phospholipase A2. Protein Sci. 17(9), 1586–1595. https://doi.org/10.1110/ps.035576.108 (2008).

Malakhov, M. P. et al. SUMO fusions and SUMO-specific protease for efficient expression and purification of proteins. J. Struct. Funct. Genom. 5(1–2), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JSFG.0000029237.70316.52 (2004).

Panavas, T., Sanders, C. & Butt, T. R. SUMO fusion technology for enhanced protein production in prokaryotic and eukaryotic expression systems. Methods Mol. Biol. 497, 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-59745-566-4_20 (2009).

Zuo, X. et al. Enhanced expression and purification of membrane proteins by SUMO fusion in Escherichia coli. J. Struct. Funct. Genom. 6(2–3), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10969-005-2664-4 (2005).

Mossessova, E. & Lima, C. D. Ulp1-SUMO crystal structure and genetic analysis reveal conserved interactions and a regulatory element essential for cell growth in yeast. Mol. Cell. 5(5), 865–876. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80326-3 (2000).

Ingram, J. R., Schmidt, F. I. & Ploegh, H. L. Exploiting nanobodies’ singular traits. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 36, 695–715. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053327 (2018).

Muyldermans, S. Nanobodies: Natural single-domain antibodies. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82, 775–797. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-063011-092449 (2013).

Steyaert, J. & Kobilka, B. K. Nanobody stabilization of G protein-coupled receptor conformational states. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 21(4), 567–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbi.2011.06.011 (2011).

Sheng, W. & Liao, X. Solution structure of a yeast ubiquitin-like protein Smt3: The role of structurally less defined sequences in protein-protein recognitions. Protein Sci. 11(6), 1482–1491. https://doi.org/10.1110/ps.0201602 (2002).

Butt, T. R., Edavettal, S. C., Hall, J. P. & Mattern, M. R. SUMO fusion technology for difficult-to-express proteins. Protein Exp. Purif. 43(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pep.2005.03.016 (2005).

Futcher, A. B. & Cox, B. S. Copy number and the stability of 2-micron circle-based artificial plasmids of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Bacteriol. 157(1), 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.157.1.283-290.1984 (1984).

Geiss-Friedlander, R. & Melchior, F. Concepts in sumoylation: a decade on. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8(12), 947–956. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm2293 (2007).

Johnson, E. S. & Gupta, A. A. An E3-like factor that promotes SUMO conjugation to the yeast septins. Cell 106(6), 735–744. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00491-3 (2001).

Newman, H. A. et al. A high throughput mutagenic analysis of yeast sumo structure and function. PLoS Genet. 13(2), e1006612. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1006612 (2017).

Ingram, J. R. et al. Allosteric activation of apicomplexan calcium-dependent protein kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112(36), E4975–E4984. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1505914112 (2015).

Larkin, M. A. et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 20. Bioinformatics 23(21), 2947–2948. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 (2007).

Madeira, F. et al. The EMBL-EBI Job Dispatcher sequence analysis tools framework in 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 52(W1), W521–W525. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae241 (2024).

Giudicelli, V., Brochet, X. & Lefranc, M. P. IMGT/V-QUEST: IMGT standardized analysis of the immunoglobulin (IG) and T cell receptor (TR) nucleotide sequences. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2011(6), 695–715. https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.prot5633 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH grant 5DP1AI150593-05. The authors thank the Center for Macromolecular Interactions at Harvard Medical School for microscale thermophoresis measurements. We thank the Bio-molecular NMR facility & Dana-Farber Cancer Institute NMR core for the NMR measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.S., H.P., J.L.A. contributed to conception and design of experiments. P.S., Z.J.S, I.S., A.Y.T, C.W., J.G., and N.P. performed experiments. P.S. and H.P. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The animal study was approved by IACUC University of Massachusetts Amherst. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. All methods reported are in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Suresh, P., Jim, S.ZY., Sahay, I. et al. Growth inhibition of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by SUMO-specific nanobodies. Sci Rep 15, 18368 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02380-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02380-6