Abstract

Some studies have found that patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have changes in levels of red blood cell (RBC) and hemoglobin (HB), and some inflammatory indexes are increased. However, the results of relevant studies are not uniform. The aim of this study is to investigate the changes of RBC, HB, and commonly used inflammatory indexes in patients with AD and their correlation with the severity of cognitive impairment. A total of 225 subjects with AD and 2000 healthy controls were included. Dementia severity was evaluated by Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). The RBC count and HB concentration of subjects were detected, and inflammatory indexes including neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet/lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and monocyte/lymphocyte ratio (MLR), systemic immune inflammation index (SII), systemic inflammation response index (SIRI), and pan-immune-inflammation value (PIV) were calculated. RBC count, HB concentration, NLR, PLR, MLR were independent influencing factors for AD. RBC count and HB concentration are significantly associated with the severity of cognitive impairment in AD patients. RBC count has a significant effect on the severity of cognitive impairment without considering the education level, but their effects on the severity of cognitive impairment are no longer significant when the education level is considered. The RBC count and HB concentration of AD patients are decreased, and are correlated with the severity of cognitive impairment. In addition, some inflammatory indexes are associated with the risk of AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Growing evidence suggests that inflammatory processes may play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)1. Neuroinflammation mediated by central nervous system astrocytes and microglia has been strongly implicated in AD development. These activated glial cells contribute to neuronal damage by disrupting the neuronal microenvironment, subsequently promoting oxidative stress and directly inducing apoptotic pathways2. Notably, both localized neuroinflammation and systemic inflammatory responses appear to be concurrently activated during AD progression3. This is supported by the observed overexpression of pro-inflammatory cytokines not only in brain tissue but also in peripheral blood samples from AD patients4.

Studies have shown that there is a correlation between the level of peripheral blood immune cells and the risk of AD5. While established peripheral AD biomarkers include plasma Aβ42, p-Tau217, p-Tau181, and p-Tau231, their clinical utility remains limited due to technical challenges in detection6. Comprehensive inflammatory indices—originally developed to differentiate infection types (bacterial vs viral), assess disease severity (e.g., in respiratory or oncological conditions), and monitor treatment responses—offer practical advantages7,8,9. These readily measurable and cost-effective indices, including: neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet/lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and monocyte/lymphocyte ratio (MLR), systemic immune inflammation index (SII), systemic inflammation response index (SIRI), and pan-immune-inflammation value (PIV) have gained widespread clinical and research applications. Although previous studies have investigated selected inflammatory indices (particularly NLR, PLR, and MLR) in AD, findings remain inconsistent. Notably, the potential utility of more comprehensive indices (SII, SIRI, PIV) as AD biomarkers remains underexplored, highlighting a critical knowledge gap in the field10,11.

Furthermore, accumulating evidence has consistently demonstrated alterations in red blood cell (RBC) and hemoglobin (HB) levels in patients with AD. Notably, the work by Qiang and Shah established a significant association between reduced Hb concentrations and both increased AD risk and dementia severity12,13. While low hemoglobin levels are established as a biomarker of frailty in elderly populations, the potential independent association between hemoglobin concentrations and both Alzheimer’s disease risk and cognitive decline remains to be fully elucidated.

In summary, current research on novel systemic inflammatory indices (SII, SIRI, PIV) in Alzheimer’s disease remains remarkably limited. Furthermore, existing evidence regarding the association between erythrocyte parameters/hemoglobin concentrations and cognitive impairment severity in AD patients continues to be inconclusive. The present study was specifically designed to address these critical knowledge gaps by: (1) evaluating the potential utility of these emerging systemic inflammatory markers as AD biomarkers, and (2) providing additional evidence for the relationship between hematological parameters and cognitive dysfunction in AD pathogenesis.

Methods

Participants

A total of 225 patients with AD hospitalized in Affiliated Xiaoshan Hospital, Hangzhou Normal University from January 2020 to October 2024, and 2000 age-matched older adults without AD or other cognitive impairment from the nearby community were recruited in this study. The study participants were exclusively of Han Chinese ethnicity recruited from Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China. According to epidemiological data, the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease among individuals aged 60 years and older in the Han Chinese population is approximately 3.9%14. The inclusion criteria for AD group were: meeting the AD diagnosis of the National Institute of Neurology and Language Disorders, Stroke, and Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA)15. Exclusion criteria for AD group were: (1) dementia caused by cerebrovascular lesions (e.g., vascular dementia confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)); (2) secondary dementia attributable to thyroid dysfunction, neurosyphilis, or HIV-associated dementia; (3) comorbid schizophrenia, alcoholic mental disorder, mental retardation, mood disorder and other mental disorders; (4) having a history of acute infection or taking antibiotics within 1 month before enrollment; (5) patients with autoimmune dysfunction or use of immunomodulatory drugs within three months before enrollment; (6) diagnosed with malignancy. The inclusion criteria of control group were: (1) age ≥ 60 years old; (2) Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≥ 28. The exclusion criteria of control group were the same as 3 ~ 6 of AD group.

Collection of subjects’ general information

We systematically collected demographic and clinical data from AD patients, including:

-

(1)

Basic characteristics (gender, age, marital status, educational attainment: (1) less than primary school, (2) primary school, (3) junior high school, (4) senior high school, and (5) college/university);

-

(2)

Medical history (hypertension, diabetes mellitus);

-

(3)

Lifestyle factors (alcohol consumption, smoking status);

-

(4)

Anthropometric measures (body mass index (BMI));

-

(5)

AD-specific parameters (disease duration, use of anti-dementia medications such as donepezil, memantine, and galantamine).

Additionally, given the potential confounding effects on inflammatory cells and platelet function, we documented the use of antipsychotic medications, mood stabilizers, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) among AD patients.

Assessment of dementia symptoms

MMSE was used to evaluate the cognitive impairment level of patients with AD. MMSE consists of 30 items, and the maximum score is 30. Subjects receive 1 point for each item for correct answers and 0 point for incorrect or no answers. Higher scores on MMSE represent better cognitive function. In this study, MMSE score ≥ 21, 20 ≥ MMSE score ≥ 10, and MMSE score ≤ 9 represented mild, moderate, and severe cognitive impairment, respectively16.

Detection of biochemical indexes

Each subject was asked to abstain from food after 8:00 p.m. and water after 10:00 p.m. and to complete elbow vein blood collection by 7:00 a.m. the following morning. The blood indicators examined in this study included high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), counts of white blood cells, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, RBC, HB, platelets, fasting blood glucose (FBG), serum total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), triiodothyronine (T3), thyroxine (T4), free triiodothyronine (FT3), and free thyroxine (FT4).

Calculation of inflammatory indices

The inflammatory indices used in this study included NLR (neutrophil count/lymphocyte count), PLR (platelet count/ lymphocyte count), MLR (monocyte count/lymphocyte count), SII (platelet count*neutrophil count/lymphocyte count), SIRI (monocyte count*neutrophil count/lymphocyte count), and PIV (neutrophil count*monocyte count* platelet count/ lymphocyte count).

Study procedure and statistical analysis

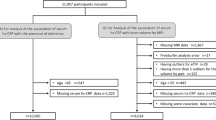

In this study, missing values were filled in using multiple interpolation, and all statistical analyses were performed on SPSS25.0. The main flow of this study was shown in Fig. 1. First, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to detect the normality of all continuous variables in AD and control group. Then, T test and Mann–Whitney U test were used to test continuous variables that conformed to normal distribution and those that did not, respectively, and Chi-square test was used to test categorical variables. To reduce false positive rates, P values in the above statistical results were corrected by Bonferroni correction. Then, in order to explore the independent risk factors of AD, the independent variables with significant differences in the difference analysis were included in the covariates for binary logistic regression analysis.

Flow chart of this study. In this cross-sectional study, we analyzed the differences in RBC count, HB concentration, and commonly used comprehensive inflammatory markers (NLR, MLR, PLR, SII, SIRI, PIV) between AD and control groups, and their correlation with the severity of cognitive impairment in AD patients. AD: Alzheimer’s disease; RBC: red blood cell; HB: hemoglobin; NLR: neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio; PLR: platelet/lymphocyte ratio; MLR: monocyte/lymphocyte ratio; SII: systemic immune inflammation index; SIRI: systemic inflammation response index; PIV: pan-immune-inflammation value.

In order to explore variables that differ significantly between patients with different severity of cognitive impairment, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed according to three groups of mild, moderate and severe cognitive impairment. After testing for homogeneity of variance, both Welch’s t-test and Brown-Forsythe test were performed. Multiple comparisons were performed using Tukey test and Games-Howell test for variance-aligned and non-aligned variables, respectively.

Moreover, in order to explore the related factors of the severity of cognitive impairment, multiple ordered logistic regression analysis was performed with mild, moderate and severe cognitive impairment as dependent variables and variables with significant differences in ANOVA as independent variables.

Results

Information of subjects

In the present study, there were 225 cases in AD group and 2000 cases in control group. There were 97 males, 128 females, 51 cases of diabetes and 144 cases of hypertension in the AD group, and 1002 males, 998 females, 189 cases of diabetes and 865 cases of hypertension in the control group. The average age of AD group and control group was 75.46 ± 7.58 years and 75.60 ± 5.49 years, and the average BMI was 21.77 ± 3.48 kg/m2 and 22.10 ± 2.00 kg/m2, respectively. In this study, the data of control group were complete, and there were 24 cases of incomplete data in AD group, including 3 cases of missing BMI data, 1 case of missing FBG, TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C data, and 1 case of missing TSH, FT3, FT4, T3, T4 data.

Factors associated with the risk of AD

As shown in Table 1, compared with control group, AD group had lower RBC count, HB concentration, higher NLR, PLR, MLR, SII, SIRI, PIV, and higher prevalence of diabetes and hypertension (all P < 0.001). After the above significantly different factors were included as covariates in binary logistic regression analysis, the results showed that high levels of NLR (B = 0.06, P < 0.01, OR = 1.92), PLR (B = 0.01, P < 0.001, OR = 1.01), MLR (B = 5.12, P < 0.05, OR = 167.25), diabetes (B = 0.72, P < 0.001, OR = 2.06) and hypertension (B = 0.84, P < 0.001, OR = 2.32) were independent risk factors for AD, while higher RBC count (B = − 0.85, P < 0.01, OR = 0.43) and HB concentration (B = − 0.05, P < 0.001, OR = 0.95) were protective factors of AD (Table 2).

To investigate the potential effects of pharmacological interventions (NSAIDs, anti-AD medications, mood stabilizers, and antipsychotics) on hematological and inflammatory parameters, we conducted subgroup analyses based on medication usage among AD patients. Our results demonstrated no statistically significant associations between medication use and any of the examined biomarkers, including RBC count, HB concentration, or systemic inflammatory indices (NLR, MLR, PLR, SII, SIRI, PIV) (all P > 0.05).

Factors associated with the severity of cognitive impairment in AD patients

Demographic and clinical characteristics were comparable across mild, moderate, and severe cognitive impairment groups regarding gender distribution, age, BMI, marital status, smoking status, alcohol consumption status, diabetes prevalence, hypertension prevalence, usage rates of anti-AD medications, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and NSAIDs (all P > 0.05). However, significant between-group differences were observed in education levels (P < 0.05), with patients in the more severe cognitive impairment group having lower educational level (ρ = − 0.19, P < 0.01).

In addition, the results of one-way ANOVA showed that AD patients with different severity of cognitive impairment had significant differences in duration of disease (F(2,24) = 4.22, MSE = 8.44, P < 0.05, r = 0.20), RBC count (F(2,22) = 3.38, MSE = 0.22, P < 0.05, r = 0.19), and HB concentration (F(2,32) = 4.59, MSE = 244.89, P < 0.05, r = 0.19). As shown in Table 3, further multiple comparisons showed that, patients with severe cognitive impairment demonstrated significantly longer disease duration compared to those with moderate impairment (t = 2.86, P < 0.05, d = 0.39). Additionally, WBC count was significantly reduced in the severe cognitive impairment group relative to mild impairment controls (t = − 2.84, P < 0.05, d = − 1.04). Both moderate (t = − 2.71, P < 0.05, d = − 1.00) and severe (t = − 2.95, P < 0.01, d = − 1.08) cognitive impairment groups showed significantly lower HB concentrations than the mild impairment group. In addition, multivariate ordinal logistic regression analysis showed that the duration of disease (B = 0.07, P < 0.05, OR = 1.07) and RBC count (B = − 0.47, P < 0.05, OR = 0.63) had an independent effect on the degree of cognitive impairment when the difference of education level was ignored. However, only the duration of disease (B = 0.14, P < 0.01, OR = 1.15) still had an independent effect on the degree of cognitive impairment when education was included as a covariate.

Discussion

Results from a Mendelian randomization study from the UK biobank suggested that RBC and HB distribution width were causally related to AD, while they found broad associations between most blood cell measures and brain structure12. In another study, researchers found that both lower and higher HB levels were associated with increased risk for AD13. In this study, the RBC count and HB concentration in peripheral blood of AD patients were significantly lower than those of healthy people, and low levels of RBC count and HB concentration were independent risk factors for AD risk. These results collectively confirm that AD patients experience a decrease in RBC, HB levels. A large amount of amyloid β-protein (Aβ) can be detected in RBC of AD patients, and the erythroid-Aβ complex causes oxidative damage, which eventually damages RBC and destroys the ability of RBC to transport oxygen, which may be one of the ways that RBC participate in the progression of AD17. HB can play a key role in the regulation of cerebral hypoxia by regulating cerebral hypoxia vasodilation18. Long-term hypoxia damage in important areas of the brain such as hippocampus may be one of the causes of dementia19. Interestingly, we also found that patients with higher dementia severity had lower RBC count and HB concentration; therefore, the levels of RBC and HB also seem to be correlated with dementia severity in AD patients.

Our study employed MMSE to assess cognitive function in AD patients, with particular attention to the potential confounding effect of educational attainment on test performance20. The MMSE, which incorporates literacy-dependent tasks such as reading, writing, and arithmetic, may yield artificially low scores in individuals with limited formal education due to test-taking inexperience rather than true cognitive impairment. The unadjusted analyses revealed significant independent associations between cognitive impairment severity and both RBC count and disease duration. Notably, more severe cognitive impairment was associated with longer disease duration and lower RBC counts. However, after controlling for educational attainment in multivariate models, only disease duration and educational level remained statistically significant predictors of cognitive impairment severity, while the association with RBC count was attenuated. These findings suggest that while hematological parameters (RBC count and HB concentration) may show preliminary associations with cognitive decline, educational attainment and disease progression appear to be more robust determinants of cognitive impairment severity in AD. The strong association with disease duration is biologically plausible, as AD is characterized by progressive neurodegeneration and cumulative cognitive decline over time. The observed attenuation of hematological associations after education adjustment highlights the importance of considering educational background when interpreting cognitive test results and biomarker associations in AD research. The association between educational attainment and cognitive impairment severity in AD patients relates to the fundamental concept of cognitive reserve (CR). CR represents the brain’s capacity to cope with neuropathological damage through either more efficient utilization of existing cognitive networks or recruitment of alternative neural pathways21. The protective effect of education against AD progression may be primarily mediated through enhanced CR22. Accumulating evidence suggests that lifetime experiences—including educational achievement, occupational attainment, and late-life leisure activities—collectively contribute to CR development, with higher CR conferring reduced risk of clinical dementia manifestation23,24,25. This CR framework provides a plausible explanation for the well-documented clinical phenomenon wherein AD patients with comparable degrees of neuropathological burden exhibit marked variability in cognitive impairment severity. Our findings align with this model, demonstrating education’s influence on cognitive performance even after accounting for disease duration. However, several limitations regarding CR assessment warrant acknowledgment. First, while we collected educational data for AD patients, the absence of control group education levels precluded direct between-group comparisons and statistical adjustment for this potential confounder. Second, our study did not incorporate occupational history metrics, which represent another critical component of CR. This represents an important limitation given that longitudinal studies have demonstrated individuals with low lifetime occupational attainment face 2.25-fold greater dementia risk compared to those with high occupational achievement26. These results underscore the multidimensional nature of CR and its clinical relevance in AD. Future investigations should incorporate comprehensive CR assessments including standardized educational attainment metrics, detailed occupational history, and leisure activity profiles, to better elucidate the protective mechanisms through which life experiences modulate cognitive resilience against AD pathology.

It is well known that there are no very effective methods for the treatment of many nervous system diseases such as AD. Molecular, metabolic, and even cellular therapies are in full progress27,28. Neuropsychiatric disorders and chronic inflammation are inextricably linked 29,30. A large number of previous studies have focused on the possibility of inflammatory markers as biomarkers for psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia31,32. Similarly, the occurrence and development of AD is also closely related to the inflammatory process33,34,35. The results of current studies on the characteristics of inflammatory indexes in AD are slightly different. In general, NLR is considered to have the highest potential as a biomarker in AD11,36,37. Our binary logistic regression analysis comparing AD patients with healthy controls yielded important insights into the differential predictive value of various inflammatory markers. The key findings demonstrated that NLR, MLR, and PLR emerged as significant independent risk factors for AD. In contrast, more complex systemic inflammation indices including SII, SIRI, and PIV did not have significant independent effects on AD risk after multivariable adjustment. These results suggest several important implications for AD biomarker research: First, the superior predictive performance of NLR, MLR and PLR may stem from their ability to more directly reflect the neuroinflammatory cascade in AD pathogenesis. Lymphocytes and monocytes are known to cross the blood–brain barrier and interact with central nervous system glial cells, potentially making their peripheral ratios more sensitive indicators of ongoing neuroinflammation. Second, given the responsiveness of platelets to various physiological stressors, additional platelet-derived components in PLR/SII/PIV may introduce confounding variables that are not related to AD-specific pathology. The results of this study revealed the relative simplicity and wide availability of NLR/MLR/PLR measurements in routine blood tests make them particularly attractive as potential screening tools for AD risk assessment in clinical settings. This study contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting the role of peripheral inflammation in AD, while highlighting the need for careful selection and validation of inflammatory markers for AD risk prediction. Future studies should validate the results in larger samples and different ethnic groups, and further explore the optimal cut-off values of inflammatory markers for predicting AD risk.

Unfortunately, this study did not find a significant correlation between inflammatory markers and the severity of cognitive impairment. It is worth noting that the vast majority of studies, including the present study, have used scales to assess cognitive function in AD patients38,39,40. Scale evaluation is difficult to accurately determine the degree of cognitive impairment in AD patients. Future studies should more accurately assess the degree of cognitive impairment in AD patients through neuroelectrophysiological methods, so as to more accurately analyze the correlation between inflammatory indicators and cognitive impairment. In addition to this, the relationship between inflammation and cognition may follow a nonlinear temporal pattern, resulting in a failure to accurately capture their correlation in cross-sectional assessments. Alternatively, some compensatory mechanisms may also mask the inflammation-cognition relationship at some stages of AD. These may all contribute to our failure to find a correlation between inflammatory markers and the severity of cognitive impairment.

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this study. First, the diagnostic certainty for AD was limited by the absence of biomarker confirmation (e.g., cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42/p-tau217 levels) due to experimental constraints. Second, cognitive assessment relying solely on MMSE may lack precision; incorporation of advanced neurophysiological or neuroimaging measures could provide more accurate evaluation of cognitive impairment. Third, while the control group was adequately sized, the relatively small AD cohort may affect the generalizability of our findings. Finally, although we accounted for NSAIDs use among AD patients given their potential effects on inflammatory indices and platelet function, the lack of NSAIDs usage data in the control group represents a potential confounding factor that should be addressed in future studies.

In conclusion, this comprehensive analysis of peripheral blood parameters in AD patients provides novel insights into their potential as accessible biomarkers. While further validation is needed, our findings advance understanding of blood-based indicators for cognitive impairment severity assessment in AD.

Data availability

Raw data from this study can be provided with the consent of corresponding author when reasonably legal.

References

Jagust, W. Imaging the evolution and pathophysiology of Alzheimer disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19(11), 687–700 (2018).

Fakhoury, M. Inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 17(11), 959–961 (2020).

Cichoń, N., Lach, D., Dziedzic, A., Bijak, M. & Saluk, J. The inflammatory processes in atherogenesis. Pol. Merkur Lekarski 42(249), 125–128 (2017).

Denver, P. & McClean, P. L. Distinguishing normal brain aging from the development of Alzheimer’s disease: Inflammation, insulin signaling and cognition. Neural Regen. Res. 13(10), 1719–1730 (2018).

Zhang, H., Cao, F., Zhou, Y., Wu, B. & Li, C. Peripheral immune cells contribute to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 62, 264–270 (2024).

Jack, C. R. et al. Revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease: Alzheimer’s association workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 20(8), 5143–5169 (2024).

Capone, M. et al. Baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and derived NLR could predict overall survival in patients with advanced melanoma treated with nivolumab. J. Immunother. Cancer 6(1), 74 (2018).

Zahorec, R. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, past, present and future perspectives. Bratisl Lek Listy 122(7), 474–488 (2021).

Huang, Z., Fu, Z., Huang, W. & Huang, K. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in sepsis: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 38(3), 641–647 (2020).

Ramos-Cejudo, J. et al. The neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is associated with the risk of subsequent dementia in the framingham heart study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13, 773984 (2021).

Dong, X., Nao, J., Shi, J. & Zheng, D. Predictive value of routine peripheral blood biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 11, 332 (2019).

Qiang, Y.-X. et al. Associations of blood cell indices and anemia with risk of incident dementia: A prospective cohort study of 313,448 participants. Alzheimers Dement. 19(9), 3965–3976 (2023).

Shah, R. C., Buchman, A. S., Wilson, R. S., Leurgans, S. E. & Bennett, D. A. Hemoglobin level in older persons and incident Alzheimer disease: Prospective cohort analysis. Neurology 77(3), 219–226 (2011).

Jia, L. et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and management of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in adults aged 60 years or older in China: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Public Health 5(12), e661–e671 (2020).

McKhann, G. et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of department of health and human services task force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 34(7), 939–944 (1984).

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & McHugh, P. R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 12(3), 189–198 (1975).

Stevenson, A., Lopez, D., Khoo, P., Kalaria, R. N. & Mukaetova-Ladinska, E. B. Exploring erythrocytes as blood biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 60(3), 845–857 (2017).

Hoiland, R. L. et al. Hemoglobin and cerebral hypoxic vasodilation in humans: Evidence for nitric oxide-dependent and S-nitrosothiol mediated signal transduction. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 43(9), 1519–1531 (2023).

Yang, X.-Y. et al. Huperzine A-liposomes efficiently improve neural injury in the hippocampus of mice with chronic intermittent hypoxia. Int. J. Nanomed. 18, 843–859 (2023).

Veronelli, L., Tosi, G. & Romano, D. Modeling functional loss in Alzheimer’s Disease through cognitive reserve and cognitive state: A panel data longitudinal study. Neurobiol. Aging 147, 60–67 (2024).

Seyedsalehi, A. et al. Educational attainment, structural brain reserve and Alzheimer’s disease: A Mendelian randomization analysis. Brain 146(5), 2059–2074 (2023).

Menardi, A., Pascual-Leone, A., Fried, P. J. & Santarnecchi, E. The role of cognitive reserve in Alzheimer’s disease and aging: A multi-modal imaging review. J. Alzheimers Dis. 66(4), 1341–1362 (2018).

Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 11(11), 1006–1012 (2012).

Nelson, M. E., Jester, D. J., Petkus, A. J. & Andel, R. Cognitive reserve, Alzheimer’s neuropathology, and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. 31(2), 233–250 (2021).

Carapelle, E., Mundi, C., Cassano, T. & Avolio, C. Interaction between cognitive reserve and biomarkers in Alzheimer disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(17), 6279 (2020).

Stern, Y. et al. Influence of education and occupation on the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. JAMA 271(13), 1004–1010 (1994).

Temple, S. Advancing cell therapy for neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Stem Cell 30(5), 512–529 (2023).

Yazdani, Y. et al. Curcumin and targeting of molecular and metabolic pathways in multiple sclerosis. Cell Biochem. Funct. 41(7), 779–787 (2023).

Sæther, L. S. et al. Longitudinal course of inflammatory-cognitive subgroups across first treatment severe mental illness and healthy controls. Psychol. Med. 54(12), 3519 (2024).

Lorkiewicz, P. & Waszkiewicz, N. Viral infections in etiology of mental disorders: A broad analysis of cytokine profile similarities - A narrative review. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 14, 1423739 (2024).

Özdin, S. & Böke, Ö. Neutrophil/lymphocyte, platelet/lymphocyte and monocyte/lymphocyte ratios in different stages of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 271, 131–135 (2019).

Zheng, Y. et al. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio is increased in the acute phase of schizophrenia and regardless the use and types of antipsychotic drugs. BMC Psychiatry 24(1), 876 (2024).

Haikal, C. & Weissert, R. Editorial: Aging, peripheral inflammation, and neurodegeneration. Front Aging Neurosci. 16, 1529026 (2024).

Guan, J. et al. Egln3 expression in microglia enhances the neuroinflammatory responses in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Behav. Immun. 125, 21–32 (2024).

Vergallo, A. et al. Plasma amyloid β 40/42 ratio predicts cerebral amyloidosis in cognitively normal individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 15(6), 764–775 (2019).

Li, W. et al. Associations between dietary and blood inflammatory indices and their effects on cognitive function in elderly Americans. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1117056 (2023).

Algul, F. E. & Kaplan, Y. Increased systemic immune-inflammation index as a novel indicator of Alzheimer’s disease severity. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 38, 214 (2024).

Nasreddine, Z. S. et al. The montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53(4), 695–699 (2005).

Choe, Y. M. et al. MMSE subscale scores as useful predictors of AD conversion in mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 16, 1767–1775 (2020).

Pinto, T. C. C. et al. Is the montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) screening superior to the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) in the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in the elderly?. Int. Psychogeriatr. 31(4), 491–504 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincerest thanks to the medical team, especially the subjects, who participated in this study.

Funding

The fundings for this study were provided by the Medical Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (No. 2023XY132), as well as the Major Science and Technology Project of Xiaoshan District (No. 2020311).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yali Zheng: Data collection, statistical analysis and original draft writing. Yongxiang Yu: Data collection. Linli Gao: Data collection. Ming Yu: Preparation of figure and tables. Lijun Jiang: Project design. Quanfeng Zhu: Project design and manuscript revision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

All procedures involving subjects in this study were carried out in accordance with relevant laws and regulations and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. This study was approved by the medical ethics committee of Affiliated Xiaoshan Hospital, Hangzhou Normal University (approval NO: 2024027), and each participant has signed a written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Y., Yu, Y., Gao, L. et al. Association of red blood cell count, hemoglobin concentration, and inflammatory indices with cognitive impairment severity in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep 15, 17425 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02468-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02468-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Intelectin-1 and systemic inflammation indices as potential biomarkers in alzheimer’s disease

Metabolic Brain Disease (2026)