Abstract

We investigate the utility of deep neural networks (DNNs) in estimating the Jaynes-Cummings Hamiltonian’s parameters from its energy spectrum alone. We assume that the energy spectrum may or may not be corrupted by noise. In the noiseless case, we use the vanilla DNN (vDNN) model and find that the error tends to decrease as the number of input nodes increases. The best-achieved root mean squared error is of the order of \(10^{-5}\). The vDNN model, trained on noiseless data, demonstrates resilience to Gaussian noise, but only up to a certain extent. To cope with this issue, we employ a denoising U-Net and combine it with the vDNN to find that the new model reduces the error by up to about 77%. Our study exemplifies that deep learning models can help estimate the parameters of a Hamiltonian even when the data is corrupted by noise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There have been considerable advances in machine learning (ML) techniques recently, thanks to the explosive growth of computing power and big data1. With more computing power than ever before, it is possible to train complex models with a huge number of parameters, making deep learning (DL) the most widely used computational approach in natural language processing, image processing, and many other fields2,3,4,5. Deep learning techniques have also been applied to several disciplines of physics, such as computational physics6,7,8,9,10,11, optics and photonics12,13, geophysics14,15, and quantum physics16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. In this work, we explore the potential of DL techniques for determining the parameters of a Hamiltonian. Specifically, we investigate whether these parameters can be extracted from the energy spectrum alone. To our knowledge, this specific problem has not been addressed within the framework of supervised learning before. Reference22 addresses a similar issue but repeatedly requires information about the updated partial spectra (the N lowest eigenvalues and eigenstates) of the model Hamiltonian, while Refs. 23,24 derive the parameters from correlation data.

As a proof-of-principle demonstration, we focus on the Jaynes-Cummings (JC) Hamiltonian25, which describes a single two-level system interacting with a cavity light-field mode. This model is of fundamental importance in quantum optics26 and is given by

where \(\omega _c\) and \(\omega _a\) denote the angular frequencies of the cavity mode and the atomic transition, respectively, and g is the coupling strength between the atom and the field. \(\hat{a}^\dagger\) and \(\hat{a}\) are the creation and the annihilation operators of the cavity photons, and \(\hat{\sigma }_\pm\) the raising and the lowering operators of the two-level atom. The JC model is one of those rare examples that can be solved exactly, thanks to the fact that the total excitation number, \(a^\dagger a + \sigma _+\sigma _-\), is conserved. Its eigenvalues read

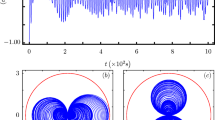

where \(\Delta = \omega _c - \omega _a\) is the cavity-atom detuning and n = 0, 1, 2, \(\cdots\). The corresponding eigenstates take the form of \(\cos \theta _n |n,g\rangle + \sin \theta _n |n-1,e\rangle\), where \(\theta _n = \frac{1}{2}\arctan ({\frac{2g\sqrt{n}}{\Delta }})\) is the mixing angle, with the ground state \(|0,g\rangle\). Figure 1 depicts the energy levels of a bare atom, a bare cavity, and the full interacting system.

Our primary goal is to investigate whether DL techniques can extract the parameters \(\omega _c\), \(\omega _a\), and g from the energy spectrum. At first glance, this task may seem trivial, given the availability of the analytic formula. However, it remains unclear whether DL can efficiently solve the inverse problem without prior knowledge of this formula. If successful, our approach could be extended to more complex Hamiltonians whose energy spectra cannot be obtained analytically, facilitating Hamiltonian reconstruction from experimentally measured spectra in systems with many Hamiltonian components. In such cases, once trained, the DL model offers a significant advantage in estimating Hamiltonian parameters compared to conventional inverse problem-solving methods. Furthermore, to deal with experimental data which are inevitably corrupted by noise, we introduce Gaussian noise to the input data, i.e., the energy eigenvalues. Conventional methods of retrieving Hamiltonian parameters are ineffective in this case, whereas our approach accomplishes the task without postprocessing27.

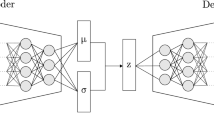

One of the challenges of ML is dealing with noisy and incomplete data, which can arise, for example, from experimental imperfections or limitations in resources28. To overcome this challenge, one possible approach is to use deep neural networks (DNNs)29,30 along with denoising autoencoders (DAEs)30,31. DNNs are powerful machine learning models that can learn complex nonlinear functions from data32,33,34. A DNN consists of multiple layers of artificial neurons that process the input data through activation functions and weights. This structure can typically be trained by back-propagating the loss function after calculating the loss between the predicted values and the ground truth. A DAE is a particular type of DNN designed to remove noise from corrupted data (see Fig. 2). It is divided into an encoder part that maps the noisy input data to a higher-dimensional latent space and a decoder part that maps the latent space back to the original data space. The aim of a DAE is to reconstruct the original clean data from noisy data by minimizing reconstruction errors. If the original input is called X and the denoised output is called \(\hat{X}\), the reconstruction error is given by the expectation value of a loss function l:

Figure 2 shows the structure of a standard overcomplete denoising autoencoder. In an overcomplete (undercomplete) autoencoder, the number of nodes in each layer increases (decreases) toward the center. Generally, an autoencoder trains a model to generate an output that matches or closely resembles the input, enabling it to learn to extract valuable features from the input data. To achieve this, an undercomplete structure is often employed, as it can learn a compact representation of the domain data within a latent space. However, to deal with noisy data, it is better to use a regularized autoencoder in an overcomplete form. By using a larger latent representation, the latter captures finer details and more complex aspects of the input. This redundancy, combined with a denoising approach to regularization, helps the network learn more robust and generalizable features, making it less sensitive to noisy or incomplete data. References35,36,37 show that overcomplete denoising autoencoders outperform undercomplete models on a variety of datasets. In this study, we will import only the learning mechanism of the DAE, which learns through back-propagation by calculating the loss function, and utilize a variation of the U-Net model38 as the backbone of our model. For convenience, we will refer to such a model as a denoising U-Net (D-UNet) model.

In this work, we investigate the performance of both the vanilla DNN (vDNN) model and the denoising DNN (dDNN) model–which integrates a pre-trained D-UNet model with a vDNN model–in learning the parameters of the JC Hamiltonian. Specifically, our goal is to train models to learn \(\omega _c\), \(\omega _a\), and g of the JC Hamiltonian from its energy spectrum, which may or may not be corrupted by Gaussian noise. For noiseless datasets, we employ the vDNN, whereas for noisy datasets, we utilize dDNNs. In the latter case, we also compare the performances of vDNNs against the dDNNs.

Methods

Data

To create a training dataset, the eigenvalues are first sorted from the ground state energy \(e_0\) in the ascending order, i.e., \(e_{i+1} \ge e_i\). We then obtain up to 96 values of \(\Delta e_i = e_{i+1} - e_i\) and \(\Delta e^2_i = e_{i+1}^2 - e_i^2\), where \(i = 0, 1, 2, \cdots\), and use them as input data. Note that while the energy difference \(\Delta e_i\) is an obvious choice, we also use the difference between the squared energies \(\Delta e^2_i\), as such ‘feature engineering’ is known to be helpful in some cases39. It turns out that the feature \(\Delta e_i^2\) produces better results than the simple one \(\Delta e_i\). While the reason for this is difficult to ascertain, the nonlinearity introduced at the outset appears to facilitate more effective learning. To make learning efficient, we restrict the parameter values \(\omega _c\) and \(\omega _a\) to the range of [0.1, 1). Every experimental system has inherent upper and lower limits for these parameters, which can always be renormalized to fit within the range. This will effectively set the energy scale. For g, we choose [0.001\(\omega _+\), 0.1\(\omega _+\)), where \(\omega _+ = \frac{\omega _c + \omega _a}{2}\), to remain within the valid regime of the JC model26,40. The training dataset has a million items of randomly chosen sets of parameters, 20% of which are used as a validation set, and the test dataset, which is used for checking our model’s performance, independent of the training phase, has 20,000 items. We add Gaussian noise to the input data, where the noise has zero mean and variance \(\epsilon\), in order to generate noisy data.

dDNN architecture and training

As shown in Fig. 3, our dDNN model consists of two submodules: a D-UNet and a fully connected feedforward neural network (FNN). Through the denoising process, the D-UNet module converts corrupted input \(\tilde{X}\) into a denoised output \(\hat{X}\).

Schematic diagram of our dDNN model. A D-UNet receives noisy input and outputs the denoised data. A separately trained FNN takes the resulting output and predicts the sought-after parameters. In the D-UNet diagram, \(\text {D}_1\), \(\text {D}_2\), \(\text {D}_3\), and N represent the dimensions of each layer’s output. The green trapezoids inside the D-UNet indicate that the number of nodes in each layer increases toward the model’s center. A more detailed structure of the D-UNet module is shown in the inset, indicating how the layers are connected. A skip connection, denoted by a dotted arrow, indicates that the layer is connected to a non-neighboring layer.

The backbone of the D-UNet module is derived from the U-Net model, which was originally introduced for biomedical segmentation applications38. Since it was originally intended for image processing, the standard U-Net comprises a 2D convolutional neural network (CNN). However, because we are dealing with one-dimensional data, we use an ordinary fully connected (FC) layer instead of a CNN layer. Furthermore, while the standard U-Net model reduces the sizes of the matrices towards the center of the U-shaped structure, we do the opposite and increase the number of nodes towards the center as in an overcomplete DAE. In the standard U-Net model, CNN layers facing each other in the U-shaped structure (hence the name) are connected by copy and crop operation. This operation involves truncating the larger feature map on the contracting path at the edges to match the dimensions of the feature map on the expansive path, followed by concatenation (see Ref. 38 for more information). In this case, information about the internal structure of the data may be lost during the cropping process, so we equalize the dimensions between the facing layers and connect them with skip connections41. A skip connection, also known as a residual connection, is a connection between layers that are far apart, unlike in a typical FNN where each layer is connected sequentially.

The remaining submodule of the dDNN model, FNN, aims to find the three parameters \(\omega _c\), \(\omega _a\), and g of the JC Hamiltonian given noiseless input data. For the dDNN model used in this study, each submodule is first trained separately, and then the two modules are combined in the sense of transfer learning42. No additional training is performed on the overall structure. Structuring the model this way provides several advantages. First, it reduces the number of model parameters trained simultaneously, lowering computational costs and accelerating training. Second, it helps reduce overfitting, a common issue when dealing with excessive model parameters. Finally, the modularity of our design, with each module handling a specific function, enables the reuse of individual components, enhancing flexibility and adaptability.

Activation functions that introduce non-linearity are crucial in DL. We use two types of activation functions. The first is a modified version of a rectified linear unit (ReLU) called LeakyReLU43 defined as

where \(\omega ^{(i)}\) is the weight vector for the ith layer. The second is called Gaussian error linear unit (GELU)44 and is defined as

where \(\text {erf}(x)\) is the error function. Both functions have a non-zero slope when \(x < 0\), but the shape of the function is smoother near \(x=0\) for GELU.

For an optimizer, we use an improved version of the widely used Adam45 optimizer, AMSGrad46, defined as follows:

\(f_t\) is the loss function, \(\beta _{1t}\) and \(\beta _2\) are decay rates, and \(\alpha\) is the learning rate. \(m_t\) and \(v_t\) are called the first and second momentum, respectively: \(m_t\) is responsible for controlling the speed of convergence through gradient smoothing, and \(v_t\) is responsible for annealing the learning rate.

The loss function between the target and predicted values is chosen among the Smooth\(L_1\) loss47, \(L_1\) loss, and the Huber loss48. In most of our cases, Smooth\(L_1\) loss turns out to be the optimal choice, which reads

Smooth\(L_1\) has the advantage of being less sensitive to outliers than \(L_2\) loss.

Finally, to evaluate the performance of the trained model, we use the standard root mean squared error (RMSE). To optimize the performance of our model, it is crucial to accurately determine the model’s hyperparameters, and for this purpose, the Optuna49 framework is used. For parameter space exploration, parameter combinations are sampled using the tree-structured Parzen estimator algorithm50 and subsequently pruned using the Hyperband algorithm51. Among the hyperparameters, the learning rate, in particular, has a large impact on both the learning process and the performance of the model, so we tune it further without using a fixed value. We utilize stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts (SGDR)52 to adjust the learning rate. The algorithm first decreases the learning rate as a cosine function, returning the learning rate to its initial value every period and then decreasing it again for a longer period than the previous step. The learning rate update rule for the SGDR algorithm is given by,

where \(\eta ^i_\textrm{min}\) and \(\eta ^i_\textrm{max}\) are the minimum and maximum values of the learning rate, respectively, \(T_i\) is the recycling period, and \(T_\textrm{cur}\) denotes how many epochs have been performed since the last restart. The entire model implementation and training have been done using Pytorch53.

Results

FNN with noiseless dataset

In the noiseless case, we simply train a vDNN model on a noiseless dataset (the FNN part in Fig. 3). We use two kinds of input data (features), \(\Delta e\) and \(\Delta e^2\), and vary the number of input nodes from 12 to 96. Formally, universal approximation theorems state that neural networks in DL can approximate complex functions without explicit feature engineering32,33,34. With finite resources, however, proper feature engineering can be very helpful, as our results show. Figure 4 illustrates how the RMSE metrics for the parameters and the first 96 energy eigenvalues vary with the number of input nodes. Panel (a) shows the RMSE averaged over the three parameters \(\omega _c\), \(\omega _a\), and g, while panel (b) shows the average losses of \(\{\hat{e}_i - e_i\}\), where \(\hat{e}_i\) is the ith energy eigenvalue calculated from the predicted parameters. Using \(\Delta e\) as the input feature yields RMSE values (for the parameters) around 0.035, regardless of the number of input nodes, while using \(\Delta e^2\) reduces the values by up to 3 orders of magnitudes.

Average RMSE for the vDNN model as the numbers of input nodes are varied. (a) Average RMSE of the three parameters, \(\omega _c\), \(\omega _a\), and g. (b) RMSE of the energy spectrum. Triangles (squares) denote results using the feature \(\Delta e\) (\(\Delta e^2\)). Lines connecting the data points are drawn to aid the eye.

In producing Fig. 4a, we have calculated the average RMSE of the three parameters of the JC Hamiltonian, which contains no information regarding each parameter. The RMSE values for each parameter are displayed in Fig. 5. Interestingly, \(\omega _a\) is the least accurately learned parameter, while g and \(\omega _c\) are learned with similar accuracy. The difference is much more pronounced when the input data is \(\Delta e\), in which case the errors decrease in the order \(\Delta \omega _a> \Delta \omega _c > \Delta g\). The RMSE of all three parameters decreases when the feature is changed to \(\Delta e^2\). The decrease in the RMSE is the greatest for \(\omega _a\), which is now of the same order of magnitude as the other two parameters. The stark reduction in the average RMSE in changing the feature from \(\Delta e\) to \(\Delta e^2\) can be largely attributed to the reduction of the RMSE in \(\omega _a\).

dDNN with noisy dataset

Real-world data are often corrupted by Gaussian noise. To see whether DL techniques can cope with such noisy data, we introduce artificial additive Gaussian noise with variance \(\epsilon\) to the input data. While there are several ways to make a noise-robust model54,55,56,57,58,59, we have devised our own version of a self-supervised learning technique which we name D-UNet.

We first evaluate the denoising performance of the D-UNet only (see Fig. 3) under different noise levels. Since this stage of the dDNN is aimed at removing noise, the model is trained to minimize the loss function in the energy spectrum rather than in the parameters. The noise strength must be chosen with some care when training a denoising model. It must be sufficiently large for the model to learn meaningful representations from the data, but not so large that it degrades the information31. For Gaussian noise, we found that a noise level of \(\epsilon =0.5\) is a good choice. We trained our model with this noise strength and tested it on data with noise levels of \(\epsilon =0, 0.4\), and \(\epsilon =0.8\). It is important to note that the model was not trained on datasets with these noise levels. Figure 6 shows the reconstruction error of the energy spectrum as the number of input nodes increases. Naturally, the error values are larger than the ones obtained from training on the noiseless data (c.f. Fig. 4b). Interestingly, even though the model was trained on a noisy dataset, the RMSE is the smallest for the noiseless dataset and increases as the noise level increases.

Reconstruction error of the energy spectrum for the D-UNet model as the number of input nodes is varied. Error bars depict ±1\(\sigma\) error range. The errors obtained from input data with noise strengths \(\epsilon = 0,0.4\), and 0.8 are marked by (red) diamonds, (black) triangles, and (blue) squares, respectively. The positions of the data are slightly adjusted for ease of viewing.

Our dDNN model is completed by connecting the D-UNet with the pretrained FNN (which is trained on the noiseless dataset). The input data are noise-corrupted and the output are the three parameters of the JC model (see Fig. 3). Figure 7a shows the average RMSE of the parameters for both the vDNN model and the dDNN model. It increases with the input noise strength, \(\epsilon\), and decreases with an increasing number of input nodes. The results obtained from the dDNN model are displayed with (red) dashed lines in the same panel. Evidently, the D-UNet model has removed some of the noise. The RMSE of the energy spectrum obtained with the parameters predicted by the trained model shows a similar trend to the parameters, as depicted in Fig. 7b. One notable feature is that while the average RMSE of the parameters quickly approaches the values of the noiseless case and tends to saturate with increasing number of input nodes, the RMSE of the energy spectrum decreases linearly up to 96 input nodes.

Finally, the RMSE of each parameter is displayed in Fig. 8. Our dDNN model outperforms the vDNN model for both (somewhat arbitrary) noise strengths and all parameters. As illustrated in panels (a) and (d), \(\omega _c\) is predicted reasonably well by both models. When the number of input nodes is 96, the RMSE decreases by a factor of 5.4 (6.4) for \(\epsilon =0.4\) \((\epsilon =0.8)\ \)(see Table 1). Panels (b) and (e) show the results for \(\omega _a\), which is the least accurately predicted parameter (as in the noiseless case). However, the dDNN model performs quite well as the number of input nodes is increased. Lastly, panels (c) and (f) illustrate the results for g, which turn out to be accurately predicted by both models except when the number of input nodes is small (12), in which case the vDNN model does not work so well. Interestingly, unlike with the other parameters, the effect of noise is suppressed quite effectively for 96 input nodes, even with the vDNN model.

Summary and discussions

The RMSE values are summarized in Table 1. Since the best performances are obtained with 96 input nodes, we only consider the data from those models. In the noiseless case, the vDNN achieves the RMSE of the order \(10^{-5}\), meaning that the parameters are predicted accurately to 4-5 decimal places. Energy eigenvalues calculated from these parameters show the RMSE of the order \(10^{-4}\). In the presence of noise, the values quickly rise to the range \(1.3\times 10^{-2} \sim 2.7\times 10^{-2}\) for the parameters and \(3.0 \times 10^{-2} \sim 6.8 \times 10^{-2}\) for the energy eigenvalues. Our dDNN brings these numbers back down to \(3.0\times 10^{-3} \sim 7.6\times 10^{-3}\) for the parameters and \(5.6\times 10^{-3} \sim 1.2\times 10^{-2}\) for the energy eigenvalues. Note that the values of \(\omega _c\) and g are predicted more accurately than \(\omega _a\). The error occurs mainly in predicting the value of \(\omega _a\).

Improvement in the error in going from the vDNN model to the dDNN model is summarized in Table 2, which displays the performance improvement ratio calculated by comparing the RMSE from the dDNN model with the vDNN model. The average RMSE of the parameters is improved by up to 77%, while the RMSE of the energy eigenvalues is improved by up to 83%. This shows that our dDNN model performs more reliably on noisy inputs than the vDNN model.

In this study, we employed a dataset of 1 million samples to train our models, prompting the question: how does performance change with varying numbers of training samples? As an initial investigation, we trained the model with 0.1 million and 10 million samples without additional optimization. The results, presented in Table 3, are obtained using the \(\Delta e^2\) feature with 96 input nodes, maintaining the same model configuration. In the vDNN case, the model trained on 1 million samples performed the best, with or without the noise. We attribute this to the fact that our model has been optimized for the sample size. In the dDNN case, the performance improves with the increasing sample size, although the improvement is modest. Further optimization is expected to enhance the performance of datasets with 0.1 and 10 million samples, a topic we plan to explore in future work.

Rabi model

Our work serves as a proof of concept, demonstrating the utility of DNN models in learning the parameters of a Hamiltonian. However, the JC model has an analytic eigenspectrum, which allows for direct determination of the Hamiltonian parameters from the eigenvalues. For DL models to be of practical use, they should be capable of extracting parameters from more complex Hamiltonians with multiple terms and non-invertible eigenvalue expressions. As a step toward this goal, we apply our method to the Rabi model60, given by

It reduces to the JC model in the weak coupling regime, i.e., \(g \ll \omega _c\). Despite its deceptive simplicity, finding an analytic formula for the eigenvalues of the Rabi model has been a notoriously difficult problem, which was only solved in 201161. Although analytic solutions exist, obtaining the energy spectrum is not straightforward, as it is determined by the zeros of a transcendental function. This makes the Rabi model a suitable testbed for applying our DNN models. In addition, we also test the efficiency of our DNN models on a generalized Rabi model, called an anisotropic Rabi model, given by62,63

It reduces to the Rabi model when \(g = g'\) and its eigenvalues can also be obtained from a transcendental equation.

To demonstrate the utility of our DNN models, we performed a preliminary test–without rigorous training–by setting the range of g to [0.1, 1) and only using the feature \(\Delta e^2\). The number of input nodes is fixed to 96 and the training noise strength is set to 0.5. Even without being thoroughly trained, our DNN models predict the parameters rather well, as shown in Table 4. In the noiseless case, our vDNN model predicts the parameters with average RMSE values of \(1.65 \times 10^{-4}\) for the Rabi model and \(3.84 \times 10^{-3}\) for the anisotropic Rabi model. The average error for the isotropic Rabi model is about three times larger than that for the JC model, while the average error for the anisotropic Rabi model is twice as large as that for the Rabi model. Note that the anisotropic Rabi model contains four parameters, which likely contribute to the larger error. The performance of our dDNN model in the noisy case is also summarized in the same table. In the isotropic case, the performance improvement ratio of the dDNN model over the vDNN model is similar to that for the JC Hamiltonian, viz. \(75 - 79\%\). The ratio degrades a bit for the anisotropic case, where the numbers are \(48.8\%\) for \(\epsilon = 0.4\) and \(61.9 \%\) for \(\epsilon = 0.8\). We believe that these numbers will improve upon fine-tuning the hyperparameters such as the number of layers and nodes or the optimizer.

Conclusion

In this work, we demonstrated the deep-learning techniques’ ability to predict the parameters of the Jaynes-Cummings Hamiltonian. Input data used were eigenvalues of the JC model with or without additive Gaussian noise. Firstly, in the noiseless case, our findings revealed that the prediction performance of the vDNN model improves with an increase in the number of input nodes. Secondly, we showed that the input feature has a significant impact on the model’s performance. Specifically, the difference in the energy squared, \(\Delta e^2\), was shown to yield much better performance than the simple energy difference, \(\Delta e\).

In the noisy case, the vDNN model, which was trained using a noiseless dataset, demonstrated a certain degree of resilience to Gaussian noise in that the RMSE decreases with increasing number of input nodes. To deal with the residual noise that persists, we employed a pre-trained (with noise strength \(\epsilon =0.5\)) D-UNet model to eliminate the noise from the corrupted input data. The resulting D-UNet model was placed before the pretrained vDNN model to construct our own dDNN model. The latter was shown to outperform the vDNN model by up to 77% for \(\epsilon =0.4\) and 72% for \(\epsilon =0.8\).

Our findings indicate that DL models can be employed to learn the parameters of a Hamiltonian from its energy spectrum alone. This approach paves the way for using supervised learning to determine the parameters of highly complex Hamiltonians based solely on their energy spectra. As a step toward this goal, we showed that our DL model is capable of learning the parameters of the isotropic and anistropic Rabi models whose energy spectra are given by zeros of transcendental functions.

Additionally, we demonstrated that connecting a D-UNet–pre-trained on a noisy dataset–to a vDNN model can create a noise-robust learning model without the need for additional training. While our current implementation addresses homoscedastic noise, our DL approach can be extended to handle heteroscedastic noise—a more realistic scenario in experiments—providing a noise-adaptive method for Hamiltonian learning.

Further research directions include learning Hamiltonian parameters in the presence of decoherence and extracting parameters from time evolution dynamics. Investigating how errors scale with the number of parameters to be determined is also a crucial open question.

Data Availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to C.N.

References

Wang, X., Zhao, Y. & Pourpanah, F. Recent advances in deep learning. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybernet. 11, 747–750 (2020).

Young, T., Hazarika, D., Poria, S. & Cambria, E. Recent trends in deep learning based natural language processing. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 13, 55–75 (2018).

Rawat, W. & Wang, Z. Deep convolutional neural networks for image classification: A comprehensive review. Neural Comput. 29, 2352–2449 (2017).

Sengupta, S. et al. A review of deep learning with special emphasis on architectures, applications and recent trends. Knowl.-Based Syst. 194, 105596 (2020).

Alzubaidi, L. et al. Review of deep learning: Concepts, cnn architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. J. Big Data 8, 1–74 (2021).

Deng, C., Wang, Y., Qin, C., Fu, Y. & Lu, W. Self-directed online machine learning for topology optimization. Nat. Commun. 13, 388 (2022).

Chi, H. et al. Universal machine learning for topology optimization. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 375, 112739 (2021).

Onyisi, P., Shen, D. & Thaler, J. Comparing point cloud strategies for collider event classification. Phys. Rev. D 108, 012001 (2023).

Leuzzi, L. et al. Euclid preparation-xxxiii. Characterization of convolutional neural networks for the identification of galaxy-galaxy strong-lensing events. Astron. Astrophys. 681, A68 (2024).

Rinaldi, E. et al. Matrix-model simulations using quantum computing, deep learning, and lattice monte carlo. PRX Quantum 3, 010324 (2022).

Carleo, G. et al. Machine learning and the physical sciences. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 045002 (2019).

Jiang, L., Li, X., Wu, Q., Wang, L. & Gao, L. Neural network enabled metasurface design for phase manipulation. Opt. Express 29, 2521–2528 (2021).

Wu, G. et al. Phase-to-pattern inverse design for a fast realization of a functional metasurface by combining a deep neural network and a genetic algorithm. Opt. Express 30, 45612–45623 (2022).

Mao, B., Han, L.-G., Feng, Q. & Yin, Y.-C. Subsurface velocity inversion from deep learning-based data assimilation. J. Appl. Geophys. 167, 172–179 (2019).

Mosser, L., Dubrule, O. & Blunt, M. J. Stochastic seismic waveform inversion using generative adversarial networks as a geological prior. Math. Geosci. 52, 53–79 (2020).

Melnikov, A. A. et al. Active learning machine learns to create new quantum experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 1221–1226 (2018).

Requena, B., Muñoz Gil, G., Lewenstein, M., Dunjko, V. & Tura, J. Certificates of quantum many-body properties assisted by machine learning. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 013097 (2023).

Cimini, V. et al. Calibration of quantum sensors by neural networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 230502 (2019).

Hills, D. J., Grütter, A. M. & Hudson, J. J. An algorithm for discovering Lagrangians automatically from data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 1, e31 (2015).

Hegde, G. & Bowen, R. C. Machine-learned approximations to density functional theory Hamiltonians. Sci. Rep. 7, 42669 (2017).

Innocenti, L., Banchi, L., Ferraro, A., Bose, S. & Paternostro, M. Supervised learning of time-independent Hamiltonians for gate design. New J. Phys. 22, 065001 (2020).

Fujita, H., Nakagawa, Y. O., Sugiura, S. & Oshikawa, M. Construction of hamiltonians by supervised learning of energy and entanglement spectra. Phys. Rev. B 97, 075114 (2018).

Kwon, H. Y. et al. Magnetic Hamiltonian parameter estimation using deep learning techniques. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb0872 (2020).

Wang, D. et al. Machine learning magnetic parameters from spin configurations. Adv. Sci. 7, 2000566 (2020).

Jaynes, E. T. & Cummings, F. W. Comparison of quantum and semiclassical radiation theories with application to the beam maser. Proc. IEEE 51, 89–109 (1963).

Scully, M. O. & Zubairy, M. S. Quantum optics (Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Valenti, A. et al. Scalable Hamiltonian learning for large-scale out-of-equilibrium quantum dynamics. Phys. Rev. A 105, 023302 (2022).

Yu, W., Sun, J., Han, Z. & Yuan, X. Robust and efficient Hamiltonian learning. Quantum 7, 1045 (2023).

Bengio, Y. Learning deep architectures for AI. Mach. Learn. 2, 1–127 (2009).

Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y. & Courville, A. Deep Learning (MIT Press, 2016).

Vincent, P., Larochelle, H., Lajoie, I., Bengio, Y. & Manzagol, P.-A. Stacked denoising autoencoders: Learning useful representations in a deep network with a local denoising criterion. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 11, 3371–3408 (2010).

Hornik, K., Stinchcombe, M. & White, H. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Netw. 2, 359–366 (1989).

Cybenko, G. Approximation by superpositions of a sigmoidal function. Math. Control Signals Syst. 2, 303–314 (1989).

Leshno, M., Lin, V. Y., Pinkus, A. & Schocken, S. Multilayer feedforward networks with a nonpolynomial activation function can approximate any function. Neural Netw. 6, 861–867 (1993).

Valanarasu, J. M. J. & Patel, V. M. Overcomplete deep subspace clustering networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision 746–755 (2021).

Dupuy, M., Chavent, M. & Dubois, R. mDAE: modified Denoising AutoEncoder for missing data imputation. arXiv:2411.12847 (2024).

Gondara, L. & Wang, K. Recovering loss to followup information using denoising autoencoders. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (big Data) 1936–1945 (2017).

Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P. & Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In 18th Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI) 234–241 (2015).

Duboue, P. Feature engineering: Human-in-the-loop machine learning. In Applied Data Science in Tourism: Interdisciplinary Approaches, Methodologies, and Applications 109–127 (2022).

Casanova, J., Romero, G., Lizuain, I., García-Ripoll, J. J. & Solano, E. Deep strong coupling regime of the Jaynes–Cummings model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 263603 (2010).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 770–778 ( 2016).

Farahani, A., Pourshojae, B., Rasheed, K. & Arabnia, H. R. A concise review of transfer learning. In 2020 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI) 344–351 (2020).

Maas, A. L., Hannun, A. Y., Ng, A. Y. et al. Rectifier nonlinearities improve neural network acoustic models. In Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML) 3 ( 2013).

Hendrycks, D. & Gimpel, K. Gaussian error linear units (gelus). arXiv:1606.08415 (2016).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv:1412.6980 (2014).

Reddi, S. J., Kale, S. & Kumar, S. On the convergence of Adam and beyond. arXiv:1904.09237 (2019).

Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. In 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 1440–1448 (2015).

Huber, P. J. Robust estimation of a location parameter. In Breakthroughs in Statistics: Methodology and Distribution 492–518 (1992).

Akiba, T., Sano, S., Yanase, T., Ohta, T. & Koyama, M. Optuna: A next-generation hyperparameter optimization framework. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining 2623–2631 (2019).

Bergstra, J. Algorithms for hyper-parameter optimization. Proc. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 24, 2546 (2011).

Li, L., Jamieson, K., DeSalvo, G., Rostamizadeh, A. & Talwalkar, A. Hyperband: A novel bandit-based approach to hyperparameter optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 18, 1–52 (2018).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Sgdr: Stochastic gradient descent with warm restarts. Int. Conf. Learn. Represent. 10, 3 (2016).

Paszke, A. et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 32, 8024–8035 (2019).

Martinez-Murcia, F. J. et al. Eeg connectivity analysis using denoising autoencoders for the detection of dyslexia. Int. J. Neural Syst. 30, 2050037 (2020).

Salmon, B. & Krull, A. Direct unsupervised denoising. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 3838–3845 (2023).

Zhang, K., Zuo, W., Chen, Y., Meng, D. & Zhang, L. Beyond a gaussian denoiser: Residual learning of deep cnn for image denoising. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 26, 3142–3155 (2017).

Quan, Y., Chen, M., Pang, T. & Ji, H. Self2self with dropout: Learning self-supervised denoising from single image. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 1890–1898 (2020).

Xu, R. et al. Depth map denoising network and lightweight fusion network for enhanced 3d face recognition. Pattern Recogn. 145, 109936 (2024).

Hinton, G., Vinyals, O. & Dean, J. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. arXiv:1503.02531 (2015).

Rabi, I. I. On the process of space quantization. Phys. Rev. 49, 324–328 (1936).

Braak, D. Integrability of the Rabi model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 100401 (2011).

Xie, Q. T. et al. Anisotropic Rabi model. Phys. Rev. X 4, 021046 (2014).

Zhang, G. & Zhu, H. Analytical solution for the anisotropic Rabi model: Effects of counter-rotating terms. Sci. Rep. 5, 8756 (2015).

Acknowledgements

W.C. and C.N. acknowledge support by the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (RS-2022-II221029) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (RS-2023-00256050). C.-W.L. acknowledges support by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017R1D1A1B04032142).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.-W.L. and C.N. conceived the project. W.C. implemented the algorithm and trained the model to produce the results. All authors have contributed to analyzing the results and writing up the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, W., Lee, CW. & Noh, C. Supervised learning of the Jaynes–Cummings Hamiltonian. Sci Rep 15, 27556 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02611-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02611-w