Abstract

This study uses two-sample MR analysis with GWAS summary statistics to evaluate the causal relationship between metabolic syndrome and low back pain. A two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis used GWAS summary statistics for low back pain from the FinnGen database and metabolic syndrome data, including waist circumference, hypertension, fasting blood glucose, HDL cholesterol, and triglyceride levels. Various methods like inverse variance weighted, MR-Egger, weighted median, and mode assessed the causal relationship, with sensitivity analyses addressing heterogeneity and pleiotropy. Our analysis found a statistically significant causal association between essential hypertension (OR 2.38, 95% CI 1.42–3.96; Padj = 0.002), metabolic syndrome (OR 1.05, 95% CI 1.01–1.10; Padj = 0.023) and waist circumference (OR 49, 95% CI 1.32–1.68; Padj < 0.001) and low back pain (OR 1.41, 95% CI 1.30–1.53, Padj < 0.001). In contrast, fasting blood glucose (FBG), HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides showed no significant associations with low back pain across all MR methods. The results of sensitivity analyses indicated that the heterogeneity and pleiotropy were unlikely to disturb the causal estimate. Our study indicates that increased essential hypertension, metabolic syndrome and waist circumference is causally associated with a higher risk of low back pain. Interventions targeting metabolic syndrome components, particularly blood pressure control and weight management, could help reduce the risk of low back pain. Further research is needed to explore the underlying biological pathways linking these metabolic factors to low back pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Low back pain is a prevalent condition that affects populations across various regions—both developed and developing—and spans all age groups, from children to the elderly1. The 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study highlighted low back pain as a leading determinant of impaired health among young and middle-aged individuals2. Not merely a critical factor in medical rehabilitation, low back pain also accounts for substantial work absenteeism, positioning it as a significant global public health concern3. Reports suggest a lifetime prevalence of up to 84%, with chronic manifestations in approximately 23% of cases4,5. Therefore, the elucidation of risk and protective factors is crucial for the prevention and treatment of this condition.

Several risk factors for low back pain have been identified: prolonged static sitting6, heavy lifting7, and poor postural habits8 are among the most commonly cited. Moreover, metabolic syndrome—with its components of central obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and dysglycemia—has been implicated due to its systemic impact on inflammation, biomechanics, and vascular health9,10,11,12,13. Central obesity, particularly increased waist circumference, is increasingly recognized as a crucial factor in the development of low back pain. Recent epidemiological evidence supports the notion that individuals with larger waist circumferences have a higher incidence of low back pain14. In addition to central obesity, other components of metabolic syndrome such as dyslipidemia—reflected in abnormal levels of HDL cholesterol and triglycerides—and hypertension have also been linked to low back pain15,16. Research suggests that these factors contribute to the condition through mechanisms such as altered lipid metabolism and increased systemic inflammation, which can exacerbate pain by affecting the spinal tissues and surrounding structures17. Despite extensive data, delineating a causal relationship between metabolic factors and low back pain remains elusive, with clinical research hampered by limited sample sizes, biases, cost, and temporal constraints. Additionally, confounding variables and lifestyle factors can mask the true associations at play. This complex interaction underlines the need for comprehensive studies that can dissect these intricate relationships further.

To address these limitations, our study adopts a Mendelian Randomization (MR) framework, utilizing genetic variants as instrumental proxies for metabolic factors18,19. This method circumvents many of the confounders inherent in observational studies by employing the random segregation of alleles to deduce the potential causal impact of an exposure on an outcome20. This study employs a two-sample MR analysis using genome-wide association study (GWAS) summary statistics to evaluate the causal relationship between metabolic syndrome and low back pain.

Methods

Study design and data sources

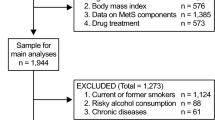

A two-sample MR study design was used (Fig. 1). For causal estimates derived from MR studies to be deemed valid, three crucial assumptions must be satisfied: (1) the genetic instruments must exhibit a robust association with the exposure of interest; (2) the genetic instruments should not be correlated with any confounding variables that might introduce bias into the results; and (3) the genetic instruments must influence the outcome solely through their impact on the exposure, without exerting any direct effects21. The drafting of this study adheres to the STROBE-MR guidelines22, and the STROBE-MR checklist is included in the supplementary materials.

The GWAS summary statistics pertaining to low back pain were sourced from the FinnGen dataset23. This investigation concentrated on European populations, encompassing 42,521 cases and 353,224 controls, yielding a total of 20,993,082 SNPs (https://storage.googleapis.com/finngen-public-data-r12/summary_stats/release/finngen_R12_M13_LOWBACKPAIN.gz).

The GWAS data regarding metabolic syndrome were compiled from prior studies, incorporating research on metabolic syndrome itself24, waist circumference25, essential hypertension (genomic sequencing data from the UK Biobank cohort), fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels26, as well as high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and triglyceride levels27. Specific details are outlined in Table 1.

Instrumental variable (IV)

In order to bolster the accuracy and reliability of the conclusions pertaining to the causal relationship, a comprehensive array of quality control measures was implemented in the selection of optimal genetic instruments. Initially, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) failing to meet the genome-wide significance threshold (P < 5 × 10−8) were excluded as instrumental variables (IVs)28. Subsequently, SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) exceeding 0.01 were retained. To mitigate the impact of linkage disequilibrium (LD), SNPs were further filtered based on an LD threshold (r2 < 0.001) and confined within a genomic region spanning 10,000kb29. In cases where the selected SNPs were absent from the summary data for the outcome, proxy SNPs exhibiting a high LD correlation (r2 > 0.8) were utilized as substitutes30. The F-statistic, calculated as R2 × (N-2)/(1-R2) for each IV, was employed to assess the strength of the instruments, with R2 denoting the proportion of phenotypic variance explained by each genetic variant in the exposure, and N representing the sample size31. Generally, an F-statistic exceeding 10 was indicative of robust instrumental variables32.

MR analyses

We performed two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) analyses using the following R packages: TwoSampleMR (v0.6.9), MRPRESSO (v1.0), LDlinkR (v1.4.0.9000), and ieugwasr (v1.0.1). The primary methodologies employed included inverse variance weighted (IVW), MR-Egger regression, weighted median (WM), and weighted mode approaches. Our principal analysis was based on the IVW method33. MR-Egger regression served to provide effect estimates and to test for directional pleiotropy through the MR-Egger intercept test. A non-significant MR-Egger intercept (P > 0.05) indicates no evidence of pleiotropy, as detailed in34. Weighted median analysis was utilized to assess causality, assuming validity in at least half of the instrumental variables (IVs)21. To visualize the causal relationships and the influence of each single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) on the outcome, forest, scatter, and funnel plots were generated. Additionally, we applied the False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction method to adjust P-values for multiple testing, considering findings with P < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Sensitivity analyses

Pleiotropy detection was conducted via MR-Egger, where a significant intercept (P < 0.05) is indicative of pleiotropy34. Cochran’s Q test was utilized to evaluate heterogeneity among IVs for each phenotypic exposure, with a P value above 0.05 signifying an absence of heterogeneity35. MR-PRESSO was employed to identify and eliminate outliers (P < 0.05) and to adjust for horizontal pleiotropy36. A leave-one-out analysis was performed to determine the influence of each SNP on the overall causality by excluding each SNP sequentially before conducting MR analyses on the remaining SNPs37.

Results

Selection of instrumental variables

Detailed information regarding the number of IVs and proxy relationships for each exposure is summarized in the Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2. The mean F-statistic values for these analyses are as follows: Metabolic syndrome is 73.4, waist circumference is 57.04, essential hypertension is 48.2, fasting blood glucose is 137.0, HDL cholesterol is 148.6, and triglycerides is 160.4.

Causal effects of MetS on low back pain

For essential hypertension, the IVW method (Table 2) indicates a potential causal effect on low back pain with an OR of 2.38 (95% CI 1.42–3.96; P_adj = 0.002) (Figs. 2A and 3A). Even after FDR adjustment, the causal association remains significant. Similarly, the Weighted Median method supports the causal inference between essential hypertension and low back pain (Table 2). Cochran’s Q test indicated potential heterogeneity, while MR-Egger did not detect pleiotropy (Table 3). MR-PRESSO analysis identified two outliers potentially causing pleiotropy (Table 4). After excluding these outliers, a reanalysis still found significant association (Supplementary Table 3). Moreover, Cochran’s Q test still suggested heterogeneity (Supplementary Table 4), and MR-PRESSO analysis indicated ongoing pleiotropy effects, though no significant outliers were detected (Supplementary Table 5). The funnel plot and leave-one-out plot also demonstrated the robustness of the analyses (Supplementary Fig. 1A and 2A).

As shown in Table 2, we found no causal association between fasting blood glucose (FBG) and low back pain. The Cochran’s Q test indicated the absence of heterogeneity among the instrumental variables (IVs) (Table 3), and no pleiotropy was detected by MR-Egger and MR-PRESSO analyses (Tables 3 and 4) (Figs. 2B and 3B). The funnel plot and leave-one-out plot both suggest the reliability of our results (Supplementary Fig. 1B and 2B).

For HDL cholesterol, the IVW analyses indicated the lack of a causal relationship between HDL cholesterol and low back pain (Table 2) (Figs. 2C and 3C). However, significant heterogeneity was detected, with no significant pleiotropic effect (Table 3) (Supplementary Fig. 1C). An outlier correction in the MR-PRESSO analyses did not reach statistical significance (Table 4). The leave-one-out plots suggested that there was no abnormal IV in this analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2C).

In the case of metabolic syndrome, the IVW method produced an OR of 1.05 (95% CI 1.01–1.10; P_adj = 0.023), with similar non-significant results from other methods (Table 2). The scatter plot and forest plot also indicate the association with low back pain (Figs. 2D and 3D). Cochran’s Q test indicated potential heterogeneity, while MR-Egger did not detect pleiotropy (Table 3). MR-PRESSO analyses identified four outliers potentially causing pleiotropy (Table 4). After excluding these outliers, a reanalysis still found significant causal association (Supplementary Table 3). Moreover, Cochran’s Q test still suggested heterogeneity (Supplementary Table 4), and MR-PRESSO analysis indicated ongoing pleiotropy effects, though no significant outliers were detected (Supplementary Table 5). Funnel plots (Supplementary Fig. 1D) indicate the absence of heterogeneity and pleiotropy in our results. The leave-one-out plots suggested that our results were not driven by a single SNP (Supplementary Fig. 2D).

IVW analysis showed that triglycerides have no significant causal effect on low back pain across all MR methods used (Table 2) (Figs. 2E and 3E). The Cochran’s Q test indicated potential heterogeneity, while MR-Egger did not detect pleiotropy (Table 3). MR-PRESSO analyses did not identify any outliers potentially causing pleiotropy (Table 4). The funnel plot suggests that the causal estimate was not influenced by any bias (Supplementary Fig. 1E), and the leave-one-out plot confirmed the reliability of our results (Supplementary Fig. 2E).

For waist circumference, the initial analysis revealed a significant association between waist circumference and low back pain, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.41 (95% CI 1.30–1.53, P_adj < 0.001) (Table 2), which was also supported by the scatter plots (Fig. 2F) and forest plots (Fig. 3F). The Cochran’s Q test indicated potential heterogeneity, while MR-Egger did not detect pleiotropy (Table 3). MR-PRESSO analyses identified three outliers potentially causing pleiotropy (Table 4). After excluding these outliers, a reanalysis still found a significant association (Supplementary Table 3). Moreover, Cochran’s Q test still suggested heterogeneity (Supplementary Table 4), and MR-PRESSO analysis indicated ongoing pleiotropy effects, though no significant outliers were detected (Supplementary Table 5). The funnel plots (Supplementary Fig. 1F) and leave-one-out plot (Supplementary Fig. 2F) further confirmed the robustness of our results.

Discussion

In this study, the causal relationship between components of metabolic syndrome and low back pain was explored by two-sample MR Analysis using the latest Finnish R12GWAS data for low back pain. Among the various metabolic factors explored, essential hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and waist circumference emerged statistically significant, underscoring their potential role in the etiology of low back pain.

Consistent with broader epidemiological evidence, our findings align with studies that have highlighted a correlation between abdominal obesity and low back pain. An 11-year longitudinal study demonstrated an increased risk of low back pain associated with abdominal obesity, defined by waist circumference38. A cross-sectional study found a 46% increase in radicular pain among participants with abdominal obesity39, and research comparing individuals with and without nonspecific low back pain identified abdominal adiposity as a significant and independent factor in the severity of pain40. Australian research observed notable correlations between the abdominal-to-lumbar adiposity ratio and self-reported pain41. The accumulation of adipose tissue in the abdominal region might impose mechanical strain on the lower back and augment the risk of pain. Additionally, the inflammatory milieu associated with abdominal adiposity could intensify nociceptive processes, exacerbating pain perception.

However, not all studies corroborate these findings. For instance, one MR study investigating BMI and obesity-related traits found no statistically significant results for waist circumference in relation to low back pain42. This discrepancy may arise from differences in study designs, such as variations in sample sizes, or the genetic instruments employed, which can influence the strength and detection of causal relationships. Furthermore, twin studies have indicated a larger waist-to-hip ratio to be associated with a lower prevalence of chronic low back pain (OR 0.67; 95% CI 0.47–0.94), without a discernible impact on waist circumference43. These discrepancies may reflect variations in population characteristics and methodologies used across studies, indicating the complexity of genetic and environmental interactions influencing low back pain.

Our findings also revealed a causal relationship between essential hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and low back pain, which has been corroborated by observational clinical studies. For example, a cross-sectional study revealed an independent association between metabolic syndrome and disability due to low back pain among care workers44. Distinct differences were noted in BMI, age, waist circumference, and disease duration between chronic low back pain patients with and without metabolic syndrome45. A large-scale study involving 139,002 individuals showed a positive correlation between newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes and the incidence of chronic low back pain (HR = 1.23, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.35)46. Research from Korea suggested a negative correlation between hypertension and the prevalence of low back pain (OR 0.79; 95% CI 0.70–0.90)47, while a cross-sectional study found significant relationships between hypertension and increased intensity and duration of low back pain48. These associations might be underpinned by shared genetic loci or metabolic pathways influencing both metabolic syndrome components and low back pain.

Conversely, the lack of significant associations for factors such as fasting blood glucose, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides suggests that while these are integral to metabolic syndrome, they may not directly influence the etiology of low back pain in a genetic context. Although no statistically significant differences were observed for the other exposures, certain clinical studies have underscored the need for continuing exploration into the multifaceted nature of these association. In a Japanese middle-aged population, low HDL-C and high LDL-C/HDL-C ratios were significantly associated with low back pain16. Furthermore, the intensity of pain in low back pain patients correlated with higher BMI, serum total cholesterol, and triglyceride levels49,50. These findings suggest that metabolic factors might influence low back pain through mechanisms that are not directly detectable through genetic associations. For example, metabolic dysregulation could lead to inflammatory states that exacerbate pain sensations, or it might alter biomechanical properties of the musculoskeletal system, thereby increasing vulnerability to pain. Moreover, the interplay of metabolic and lifestyle factors such as diet and physical activity might modulate these effects, complicating the causal pathways.

Building upon established epidemiological evidence, a more prominent role of abdominal obesity over general obesity has been suggested in the risk of developing various health conditions, including cardiovascular diseases, major adverse cardiac events, and metabolic syndrome51,52. Furthermore, abdominal obesity has been implicated in the accelerated decline of muscle strength and a significant increase in spinal loading53. Adipose tissue, now recognized as an endocrine organ, exhibits increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) when hypertrophied, potentially leading to a state of chronic low-grade inflammation54. Additionally, individuals with obesity often have elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP)55, a marker not only indicative of the pro-inflammatory state associated with obesity but also a highly sensitive systemic marker of inflammation and tissue damage56. This is due to injured tissue summoning immune cells like macrophages and neutrophils, which play a pivotal role in tissue healing. Such inflammatory processes could contribute to the pathogenesis of low back pain, offering a potential explanation for the observed association between waist circumference and this condition.

The potential impact mechanisms linking obesity and pain perception may also involve shared genetic loci that influence both fat distribution and sensitivity to pain. Recent studies suggest that certain genes implicated in the metabolic processing of fats are also involved in the neurological pathways that modulate pain perception, highlighting a complex genetic interplay that could predispose individuals to both obesity and heightened pain sensitivity57,58. Additionally, essential hypertension and metabolic syndrome may influence low back pain through several mechanisms. For instance, systemic hypertension could impair vascular supply to the lumbar region, exacerbating degenerative changes in the spine and leading to increased pain15. Metabolic syndrome, characterized by a cluster of conditions including high blood pressure, high blood sugar, excess body fat around the waist, and abnormal cholesterol levels, could similarly contribute to musculoskeletal stress and inflammation, thus aggravating or initiating low back pain59.

This study’s primary limitation lies in its reliance on observational data for genetic instruments, which may not capture all nuances of the metabolic syndrome components’ effects on low back pain, potentially overlooking gene-environment interactions. Additionally, the MR analysis assumes no pleiotropy, an assumption that might not hold for all genetic variants used. Despite these constraints, the study’s major strength is its innovative use of a two-sample Mendelian Randomization approach, offering a robust framework to infer causality by leveraging large-scale GWAS data. The analysis relies on the random effects IVW method, designed to account for variability among genetic instruments, though showing heterogeneity. Initial analyses identified potential pleiotropic outliers; however, removing these did not alter the results, affirming the reliability of our findings. While F-statistics for most exposures exceed 10, indicating strong instruments, some exposures may still be susceptible to weak instrument bias. The study predominantly used data from European populations, mainly British and Finnish cohorts, raising questions about the applicability of the findings to other ethnic groups due to different genetic and environmental interactions. Additionally, the study does not address survival bias or age-related heterogeneity in the effects of metabolic syndrome, which could influence the results’ generalizability and interpretation.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that hypertension and abdominal obesity (as indicated by waist circumference) may play key roles in the development of low back pain, potentially through metabolic and cardiovascular mechanisms. These findings provide a new perspective on the prevention and treatment of low back pain, emphasizing the need to focus on metabolic health—particularly hypertension and abdominal obesity—in clinical practice. They also suggest that future research should further explore the underlying mechanisms.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Hartvigsen, J. et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet (London, England) 391, 2356–2367. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30480-x (2018).

Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet (London, England) 396, 1223–1249 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30752-2.

Chenot, J. F. et al. Non-specific low back pain. Deutsches Arzteblatt Int. 114, 883–890. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2017.0883 (2017).

Puta, C. et al. Are there abnormalities in peripheral and central components of somatosensory evoked potentials in non-specific chronic low back pain?. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10, 521. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00521 (2016).

Zhou, S. et al. Mendelian randomization study on the putative causal effects of omega-3 fatty acids on low back pain. Front. Nutr. 9, 819635. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.819635 (2022).

Zheluk, A., Anderson, J. & Dineen-Griffin, S. Analysis of acute non-specific back pain content on tiktok: An exploratory study. Cureus 14, e21404. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.21404 (2022).

Brandt, M. et al. Participatory intervention with objectively measured physical risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders in the construction industry: Study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 16, 302. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0758-0 (2015).

Furtado, R. et al. Validation of the Brazilian–Portuguese version of the Gesture Behavior Test for patients with non-specific chronic low back pain. Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil) 64, 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1807-59322009000200004 (2009).

Kauppila, L. I. Atherosclerosis and disc degeneration/low-back pain–a systematic review. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 37, 661–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.02.006 (2009).

Kostova, V. & Koleva, M. Back disorders (low back pain, cervicobrachial and lumbosacral radicular syndromes) and some related risk factors. J. Neurol. Sci. 192, 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00585-8 (2001).

Pedersen, B. K. & Saltin, B. Exercise as medicine—Evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 25(3), 1–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12581 (2015).

Sun, K. et al. Tissue renin-angiotensin system (tRAS) induce intervertebral disc degeneration by activating oxidative stress and inflammatory reaction. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 3225439. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/3225439 (2021).

Zahari, S. N. et al. The effects of physiological biomechanical loading on intradiscal pressure and annulus stress in lumbar spine: A finite element analysis. J. Healthc. Eng. 2017, 9618940. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9618940 (2017).

You, Q. et al. Waist circumference, waist-hip ratio, body fat rate, total body fat mass and risk of low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Spine J. 31, 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-021-06994-y (2022).

Skrzypek, M. et al. Hypertension-mediated organ damage in relation to severity of chronic low back pain in hypertensive patients. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd11090266 (2024).

Yoshimoto, T. et al. Association between serum lipids and low back pain among a middle-aged Japanese population: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. 17, 266. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-018-0907-1 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Advances in research on fat infiltration and lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 1067373. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1067373 (2022).

Greenland, S. An introduction to instrumental variables for epidemiologists. Int. J. Epidemiol. 47, 358. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx275 (2018).

Smith, G. D. & Ebrahim, S. “Mendelian randomization”: Can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease?. Int. J. Epidemiol. 32, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyg070 (2003).

Davies, N. M., Holmes, M. V. & Davey, S. G. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: A guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 362, k601. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k601 (2018).

Bowden, J. et al. Consistent estimation in mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet. Epidemiol. 40, 304–314. https://doi.org/10.1002/gepi.21965 (2016).

Veronika, W. S. et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology using Mendelian randomization: The STROBE-MR statement. JAMA https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.18236 (2021).

Kurki, M. I. et al. FinnGen provides genetic insights from a well-phenotyped isolated population. Nature 613, 508–518. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05473-8 (2023).

Lind, L. Genome-wide association study of the metabolic syndrome in UK Biobank. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 17, 505–511. https://doi.org/10.1089/met.2019.0070 (2019).

Mbatchou, J. et al. Computationally efficient whole-genome regression for quantitative and binary traits. Nat. Genet. 53, 1097–1103. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00870-7 (2021).

Chen, J. et al. The trans-ancestral genomic architecture of glycemic traits. Nat. Genet. 53, 840–860. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00852-9 (2021).

Willer, C. J. et al. Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat. Genet. 45, 1274–1283. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2797 (2013).

Huang, S. J. et al. Assessment of bidirectional relationships between circulating cytokines and periodontitis: Insights from a mendelian randomization analysis. Front. Genet. 14, 1124638. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2023.1124638 (2023).

Chen, H. et al. Cardiac troponin i and risk of stroke: A Mendelian randomization study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 15, 1575–1582. https://doi.org/10.2147/ijgm.S351034 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Plasma homocysteine levels and risk of congestive heart failure or cardiomyopathy: A Mendelian randomization study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1030257. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1030257 (2023).

Palmer, T. M. et al. Using multiple genetic variants as instrumental variables for modifiable risk factors. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 21, 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280210394459 (2012).

Burgess, S., Small, D. S. & Thompson, S. G. A review of instrumental variable estimators for Mendelian randomization. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 26, 2333–2355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280215597579 (2017).

Burgess, S., Butterworth, A. & Thompson, S. G. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet. Epidemiol. 37, 658–665. https://doi.org/10.1002/gepi.21758 (2013).

Bowden, J., Davey Smith, G. & Burgess, S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 512–525. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv080 (2015).

Hartwig, F. P., Davey Smith, G. & Bowden, J. Robust inference in summary data Mendelian randomization via the zero modal pleiotropy assumption. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 1985–1998. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx102 (2017).

Verbanck, M. et al. Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat. Genet. 50, 693–698. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0099-7 (2018).

Papadimitriou, N. et al. Physical activity and risks of breast and colorectal cancer: a Mendelian randomisation analysis. Nat. Commun. 11, 597. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14389-8 (2020).

Shiri, R. et al. Risk factors for low back pain: A population-based longitudinal study. Arthritis Care Res. 71, 290–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23710 (2019).

Bayartai, M. E. et al. Association of accelerometer-measured physical activity, back static muscular endurance and abdominal obesity with radicular pain and non-specific low back pain. Sci. Rep. 13, 7736. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34733-4 (2023).

Uçar, İ et al. The relationship between muscle size, obesity, body fat ratio, pain and disability in individuals with and without nonspecific low back pain. Clin. Anat. (New York, NY) 34, 1201–1207. https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.23776 (2021).

Brooks, C., Siegler, J. C. & Marshall, P. W. Relative abdominal adiposity is associated with chronic low back pain: A preliminary explorative study. BMC Public Health 16, 700. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3357-6 (2016).

Zhou, J. et al. Causal associations of obesity with the intervertebral degeneration, low back pain, and sciatica: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 740200. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.740200 (2021).

Dario, A. B. et al. Are obesity and body fat distribution associated with low back pain in women? A population-based study of 1128 Spanish twins. Eur. Spine J. 25, 1188–1195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-015-4055-2 (2016).

Tsuboi, Y. et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and disability due to low back pain among care workers. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 31, 165–172. https://doi.org/10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01004 (2018).

Duruöz, M. T. et al. Evaluation of metabolic syndrome in patients with chronic low back pain. Rheumatol. Int. 32, 663–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-010-1693-x (2012).

Jacob, L. et al. Association between type 2 diabetes and chronic low back pain in general practices in Germany. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2021-002426 (2021).

Bae, Y. H. et al. Association between hypertension and the prevalence of low back pain and osteoarthritis in Koreans: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 10, e0138790. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138790 (2015).

Alsubaie, S. F. et al. The relationship between chronic diseases and the intensity and duration of low back pain. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. https://doi.org/10.23736/s1973-9087.23.07649-9 (2023).

Bruthans, T., Vránová, J. & Yamamotová, A. Objective evaluation of chronic low-back pain using serum lipids: The role of the doctor-patient relationship. Pain Res. Manag. 2023, 9972093. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/9972093 (2023).

Krikava, K. et al. Blood serum changes in patients with pain during bone fractures and acute pancreatitis. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 25, 62–69 (2004).

Choi, D. et al. Impact of discrepancies in general and abdominal obesity on major adverse cardiac events. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e013471. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.119.013471 (2019).

Paley, C. A. & Johnson, M. I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome: Exercise as medicine?. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 10, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-018-0097-1 (2018).

de Carvalho, D. H. T. et al. Does abdominal obesity accelerate muscle strength decline in older adults? Evidence from the English longitudinal study of ageing. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 74, 1105–1111. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gly178 (2019).

Galic, S., Oakhill, J. S. & Steinberg, G. R. Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 316, 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2009.08.018 (2010).

Lau, D. C. et al. Adipokines: Molecular links between obesity and atheroslcerosis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 288, H2031-2041. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.01058.2004 (2005).

Pepys, M. B. & Hirschfield, G. M. C-reactive protein: A critical update. J. Clin. Investig. 111, 1805–1812. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci18921 (2003).

Li, W. et al. The roles of blood lipid-metabolism genes in immune infiltration could promote the development of IDD. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10, 844395. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.844395 (2022).

Yan, J. et al. Cholesterol induces pyroptosis and matrix degradation via mSREBP1-driven endoplasmic reticulum stress in intervertebral disc degeneration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 803132. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.803132 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic actions of bufotenine through inhibiting lipid metabolism pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 140, 111749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111749 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by the Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Project of Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (2024QN110), Shanghai Key Laboratory of Traditional Chinese Medicine Tuina Technology for Muscle and Bone Diseases (24dz2260200), Three Year Action Plan Project for Shanghai to Further Accelerate the Inheritance, Innovation and Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine (ZY (2025–2027)–3–1–1), Shanghai’s Three Year Action Plan for Further Accelerating the Inheritance, Innovation and Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine (2021−2023) (ZY(2021–2023)-0208 and ZY(2021–2023)-0209–03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WY, XXB and MF designed the study, collected, reviewed, analysed data, and wrote the manuscript. KLJ, HTX, GGX verified data and contributed to data analysis. ZQG, XXB and MF revised the manuscript and provided valuable suggestions for study design and data analysis. ZQG, XXB and MF contributed equally, designed the project, edited the manuscript, and supervised the study. All authors have approved the final version of this paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, W., Kong, L., He, T. et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and low back pain: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep 15, 17686 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02630-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02630-7