Abstract

The research investigation of Response Surface Methodology (RSM) optimization to analyze the impact of load, Algae Oil Methyl Ester (AOME), and CuO copper oxide nano-fuel enhancement on engine performance and exhaust gas emissions, employing both normal and YSZ-coated pistons. The maximum yield observed with 96.32% AOME mix with diesel-biodiesel blends (10%, 20%, and 30%), load variations (10, 50, and 100 kg), and CuO concentrations (50, 75, and 100 ppm) Statistical and experimental data reveal that load and CuO concentrations significantly influence NOx emissions, while AOME blends enhance combustion efficiency, impacting Brake Thermal Efficiency (BTE) and Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC). In normal and coated piston types, load and CuO concentration considerably affect NOx emissions, although the thermal barrier YSZ coating improves performance at the cost of higher peak flame temperatures and NOx emissions. Experimental results show that with a 60% AOME blend, 75 ppm CuO, and a load of 50 kg, the BTE reached 32% with a BSFC of 0.21 kg/kWh for normal pistons, while YSZ-coated pistons achieved a comparable BTE of 31.1% but with higher NOx emissions (385 ppm compared to 560 ppm for normal pistons). Smoke density reductions of 12.5% were observed with YSZ-coated pistons at optimal conditions. Load, CuO concentration, and AOME blend significantly influenced key performance parameters such as BTE, BSFC, NOx, CO, HC, and smoke density. Surface plots and perturbation diagrams highlighted critical interactions, demonstrating the potential of biodiesel blends, CuO additives, and thermal barrier coatings to improve engine efficiency while minimizing smoke emissions, although at the cost of increased NOx levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In today’s industrialised world, the use of automobiles and engines has increased dramatically1. Coal, diesel, and petrol are non-renewable energy sources. Traditional energy sources have resulted in significant ecological harm2,3,4,5. Carbon dioxide is increasingly accumulating in the atmosphere alongside other Greenhouse Gases (GHGs), leading to significant global climate change6. The demand for petroleum-based resources is rapidly depleting due to the increasing energy needs, and it is projected that their supply will considerably decrease in the next decades. Most of the energy consumed in the current energy system is derived through non-renewable sources, that aren’t environmentally sustainable and contribute substantially to carbon emissions7. Furthermore, the conversion of microalgal biomass into different biofuels is optimized by pre-treatment techniques such as mechanical, thermal, and enzymatic procedures. Biodiesel possesses advantageous characteristics such as being biodegradable sustainable nature, and non-toxicity8. Due to these characteristics, they are a superior option for partially replacing petroleum fuels. Algae is becoming highly profitable for biodiesel production in developing nations9. Algae biodiesels are gaining global prominence because to their natural availability, ease of cultivation, high oxygen content, and ability to reduce emissions10. The addition of nanoparticles to Neochloris oleoabundans algae biodiesel has been studied to analyze their impact on fuel characteristics and engine performance under various loading conditions. This approach highlights the potential of algae-based biodiesel as a sustainable alternative fuel source11. There are about 80,000 species of algae worldwide, and approximately 45,000 of these species have been classified12.

TBC play a crucial role in improving the efficiency and longevity of engine pistons13. Effects of Manganese Dioxide (MnO2) as a fuel additive on enhancing diesel engine performance and reducing emissions14. They are composed of minerals including yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ), partially stabilised zirconia (PSZ), CaO/MgO–ZrO2, TiO2, Al2O3 Out of these options, YSZ is the most frequently utilised because of its poor thermal conductivity, which effectively minimises the transfer of heat to the piston15. The application of these coatings is often done by the plasma spray coating technique, which guarantees the formation of a consistent and long-lasting layer16. Below is a summary table based on various studies on TBCs. Table 1 shows that various studies on TBCs.

The utilisation of copper oxide (CuO) nanoparticles as fuel additives in biodiesel engines provides a multitude of advantages32. They improve the efficiency of combustion by serving as a catalyst, resulting in a more thorough burning of fuel and an increase in (BTE)33. As a consequence, there is a decrease in (BSFC), which indicates that less gasoline is used for each unit of power produced34. CuO nanoparticles additionally contribute to the reduction of detrimental emissions, such as (CO), (HC), and particulate matter, resulting in the production of cleaner exhaust gases35,36. In addition, they greatly decrease the concentration of smoke in the exhaust, so enhancing air quality, and optimise the process of combustion to minimise potential rises in (NOx)37. In addition, CuO nanoparticles improve the lubricating properties of biodiesel, hence decreasing the damage and deterioration of engine parts38. These advantages combine enhance the performance of biodiesel engines and decrease their impact on the environment39,40.

The study employs an experimental design that varies concentrations of AOME and CuO and uses RSM for optimization. It also incorporates a TBC made of Yttria-stabilised zirconia (YSZ) on the piston to improve thermal efficiency when using biodiesel blends. The study employs theoretical frameworks, ANOVA data, and mathematical models to clarify complex relationships, and provide visual representations of the impact of load, AOME blend, and CuO concentration on emissions and performance through surface plots and perturbation diagrams. This approach offers practical solutions to enhance the performance and environmental impact of diesel engines. The aim of the tools provide an explanation of how load, AOME blend, and CuO concentration affect emissions and performance. The study uses TBC (YSZ) in thermal barrier coatings to enhance the BTE, reduce the BSFC, and reduce the emissions of NOx, CO, smoke, and HC.

Materials and methodology

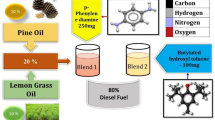

Algae are a promising biofuel source because of their accessibility and non-toxicity25. Photosynthetic algae live in water-based and coastal seas and can multiply faster under controlled circumstances26. Additionally, sludge and other water pollutants can be used to grow these organisms. Many countries use these algae as food supplements. Due of its strong smell, regular use is recommended. Pharmaceutical uses are possible due to its medicinal properties. It produces Algae Oil Methyl Ester (AOME), a promising fossil fuel substitute, and is a great biofuel. Due to its high lipid content, algae could be used as fuel and to extract methyl ester. These algae use a lot of oxygen to make methyl esters of 14–18 carbon lipids. AME preparation is shown in Fig. 1. Table 2 lists AOME’s chemical properties.

Preparation of Algal Methyl Ester (AOME): The AOME was prepared through a transesterification process using KOH as the catalyst.

In this process, the following process parameters were varied:

A - KOH (% W/v): 0.5%, 1%, and 1.5%.

B - Temperature (°C): 40 °C, 50 °C, and 60 °C.

C - Molar ratio: 8:1, 10:1, and 12:1 (methanol to oil).

D - Time (min): 60 min, 120 min, and 180 min.

Experimental setup: The transesterification was carried out using a laboratory-scale setup consisting of a reaction vessel equipped with a magnetic stirrer and a heating system. The oil was mixed with methanol and KOH under the specified conditions. The reaction was monitored, and after completion, the biodiesel was separated and purified by washing and drying.

The mathematical structure is developed using statistical analysis and experimental data to explain the elements impacting the yield (%) of a given process. Table 2 shows the input parameters of KOH, Temperature, molar ratio and time. Table 3 shows each level yield at the prescribed RSM method. Table 4 shows the analysis of variance, a mean yield of 78.10% and a standard deviation of 16.35 are displayed in the data that is presented, yielding a coefficient of variation (C.V.%) of 20.94%. R2 = 0.6202 shows that the model accounts for 62.02% of the yield variance; however, the adjusted and forecast R2 values are negative, suggesting that the model has low predictive potential. The satisfactory 3.1024 precision indicates a good signal-to-noise ratio. The ANOVA results shows in Table 5 indicate that the model is significant (p = 0.7057), and that the AC interaction (p = 0.1703) and C (Molar Ratio, p = 0.0521) are significant factors. A (KOH), B (Temperature), D (Time), as well as a few interactions and quadratic terms, are non-significant elements. Higher molar ratios are thought to increase process efficiency based on the yield-positive molar ratio effect, and the substantial AC interaction emphasises the significance of particular temperature and molar ratio combinations for yield enhancement. While a decent fit is indicated by the R2 score, it is advisable to use caution when extrapolating the model without additional validation. To maximise their interaction effects, optimisation strategies should concentrate on controlling KOH concentration, modifying temperature in parallel with time, and establishing a balance between molar ratio and time. To improve the model’s predicted accuracy and refine it further, more testing and validation are advised. The highest yield of 96.32% highlights the possible effectiveness of the determined ideal parameters, which include a molar ratio of 8, a temperature of 45 °C, a duration of 180 min, and a KOH concentration of 0.5% (W/V). These parameters might be used as a standard for further optimisation efforts. Equation 1 for a for a highest yield possible were derived from the RSM quadratic model based on the measured parameters

The 2D and 3D surface plots considering each factor (KOH concentration, molar ratio, temperature, and time) affects the yield shown in Figs. 2, 3 and 4. Surface plots help visualize the interaction between two factors while keeping other factors constant. The explanation of these plots can be interpreted with specific focus areas on KOH concentration vs. Molar Ratio, KOH concentration vs. Temperature, and KOH concentration vs. Time. In the 2D surface plot of KOH concentration vs. Temperature, Molar Ratio and Time, can see how the yield varies with changes in these two factors while keeping temperature and time constant. As the molar ratio increases, the yield generally increases, though this effect can vary with different levels of KOH concentration. For instance, at a KOH concentration of 1% and varying the molar ratio from 8 to 12, there is a general trend of increasing yield. A similar trend is seen at 0.5% and 1.5% KOH concentrations, but the extent of yield change may differ. A 3D plot provides a more detailed view, showing a surface where the yield is plotted on the z-axis, KOH concentration on the x-axis, and Temperature, Molar Ratio and Time on the y-axis. The 3D plot can reveal peaks where the combination of KOH concentration and Molar Ratio maximizes the yield. For instance, the plot might show a peak yield at a KOH concentration of 1.5% and a Molar Ratio of 12. A perturbation chart shown in Fig. 5 is a graphical representation used in response surface methodology to show the sensitivity of the response variable (yield %) to changes in each factor while keeping other factors constant at a specific reference point. It helps in understanding the effect of individual factors on the response and identifying which factors are most influential. The highest yield of 96.32% highlights the possible effectiveness of the determined ideal parameters, which include a molar ratio of 8, a temperature of 45 °C, a duration of 180 min, and a KOH concentration of 0.5% (W/V). These parameters might be used as a standard for further optimisation efforts.

Yield—a 3D surface plot, b 2D contour plot KOH vs. temperature—data analysis was performed by Design Expert (Version 13)—https://www.statease.com/software/design-expert.

Experimental setup

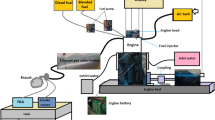

The layout shown in Fig. 6a Kirloskar engine with a single chamber and four strokes, in addition to an engine that is associated with the control panel. The engine load can be adjusted between 0 and 5.2 kW. For ease of understanding, the engine delivers 5.2 kW of power at full load, with the load settings adjustable to 0%, 50%, and 100%. The fuel mixture ratio, consisting of diesel and biodiesel, can be varied using the fuel estimator on the control panel, which controls the proportion of air mixed with the fuel. Additionally, the system allows for the configuration of key components, including the smoke meter and the inlet manifold, both of which can be monitored and adjusted through the accessible electronic control panel.

Key sensors used in the experimental setup include a load cell that measures the engine load with high accuracy. A smoke meter monitors exhaust smoke opacity, providing real-time data on particulate emissions. Temperature sensors are placed at various points in the system, including the exhaust and inlet manifold, to record temperature variations. Gas analyzers measure emissions characteristics. Flow meters measure the fuel and air flow rates, ensuring precise fuel-air mixture ratios. These components are controlled and monitored through the ECU, allowing for accurate experimental adjustments and reliable measurements.

Thermal barrier coatings

TBC play a crucial role in improving the efficiency and longevity of engine pistons. The layer thickness of these coatings typically varies from 0.02 to 1.5 mm. Barrier coatings materials are made up of minerals such as YSZ, partially stabilized zirconia (PSZ), CaO/MgO–ZrO2, TiO2, and Al2O3. Out of these options, YSZ provides a better balance of low thermal conductivity and high melting point, making it more effective at reducing heat transfer and withstanding high temperatures. The application of these coatings is often done by the plasma spray coating technique, which guarantees the formation of a consistent and long-lasting layer. Figures 7 and 8 shows the TBCs (Normal and YSZ coated) with experimental test on piston crown.

The utilisation of CuO nanoparticles as fuel additives in biodiesel engines provides a multitude of advantages32. They improve the efficiency of combustion by serving as a catalyst, resulting in a more thorough burning of fuel and an increase in (BTE)32. As a consequence, there is a decrease in (BSFC), which indicates that less gasoline is used for each unit of power produced33. CuO nanoparticles additionally contribute to the reduction of detrimental emissions, such as (CO), (HC), and particulate matter, Fig. 9 shows the copper oxide nano powder and Fig. 10 shows the SEM image of CuO Nano Powder. The optimal concentrations of AOME and CuO were determined by blending CuO nanoparticles (50–100 ppm) with PSOME20 fuel (20% AOME) using a 200 W ultrasonicator at 40 kHz, 350 rpm, and 70 °C for 1.5 h to ensure uniform dispersion. The AOME concentrations were varied at 20%, 40%, and 60%, and CuO concentrations were tested at 50, 75, and 100 ppm. Engine performance and emissions were evaluated under different load conditions (0, 50, and 100 kg). The CuO nanoparticles were characterized using SEM and XRD to analyze size, morphology, crystal structure, and phase composition, helping optimize their effects on fuel properties and engine performance.

Experimental design

The trial design, optimisation, and validation processes were all carried out using the Design-Expert® tool, version 13. Table 6 shows the data input factors and their levels. Each variable that is entered is subject to a numerical calculation. To maximise BTE while enhancing BSFC and reducing NOx, CO, smoke, and HC, the load was determined between 0 and 100%, the AOME mix biodiesel (10, 20, and 30%), and the CuO Nanoparticle (50, 75, and 100 ppm). Table 7. The result is obtained for the Normal Piston and Thermal Barrier YSZ Coated Piston.

Result and discussion

The experiment results were analysed using (ANOVA), and a variety of models were built in the design expert. The projected values were then computed using the formulae. To discover the most acceptable variable combinations, acceptability analysis was performed utilising the direct equation to achieve better results.

Performance result

Equation (2) for a Normal Piston and Eq. (3) for an yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) Coated Piston were derived from the RSM quadratic model of BTE based on the measured parameters.

The observed variations in brake thermal efficiency (BTE) can be attributed to numerous key factors related to the properties of the fuel blends used. Specifically, the increase in BTE for certain blends is due to their lower viscosity and higher calorific value compared to other mixes. This physical and chemical advantage facilitates more efficient energy conversion during combustion. However, the premixed combustion phase is decreased, and the diffusion combustion phase is increased due to a longer ignition delay, resulting in late burning. Consequently, more energy is released in the later portion of the combustion process. This late energy release is less efficient, leading to a reduction in overall thermal efficiency, particularly evident in the case of higher blends.

The investigation of brake thermal efficiency (BTE) for normal and thermal barrier YSZ pistons under different load conditions, AOME blend percentages, and CuO nanoparticle concentrations displays significant relationships and primary effects. The ANOVA results BTE shown in Table 8 for the normal piston show that the interaction between load and AOME blend (AB) strongly impacts BTE, as indicated by a p value of 0.0421. However, the primary impacts of load (A), AOME mix (B), and CuO (C), as well as their squared terms and other interactions, do not have an important effect on BTE individually. This is indicated by their p values being over 0.05. This implies that although the interplay between load and AOME mix is crucial, the efficiency is not significantly affected by individual variations in load, blend, and CuO concentration. The ANOVA results for the thermal barrier YSZ coated piston shows minor variations. There are no factors or interactions that have statistically significant effects on BTE, as all p values are greater than 0.05. It also indicates that changes in load, AOME blend percentage, and CuO concentration, whether separately or in combination, have no significant impact on the brake thermal efficiency (BTE) of the coated piston. Significantly, the residual sum of squares is larger for the thermal barrier YSZ coated piston (384.17) in comparison to the normal piston (310.24), indicating a potentially greater level of variability in the data for the coated piston. The concentrations of CuO nanoparticles do not significantly affect brake thermal efficiency (BTE) in either the normal piston or the YSZ-coated piston, as indicated by p-values greater than 0.05. While variations in AOME blend significantly impact BTE for the normal piston, the interaction between load and AOME blend is the primary factor influencing BTE. In contrast, for the YSZ-coated piston, neither AOME blend nor CuO concentration show any significant effect on BTE, with all p values exceeding 0.05.

Figures 11, 12 and 13 illustrating these facts, a sequence of 2D, 3D and perturbation diagrams can be employed. A 2D surface plot would clearly show the relationship between load and AOME blend, specifically for a fixed concentration of CuO. This figure can effectively highlight the important interaction between AB for the normal piston. Furthermore, it is essential to generate 3D surface plots that illustrate the collective impact of load, AOME mix, and CuO concentration on BTE. Perturbation plots can clearly demonstrate the ability of BTE to minor alterations in individual factors, hence enhancing comprehension of the impact of each variable and their interaction on efficiency. In this case, when a load of 50 kg was used, an AOME blend with a concentration of 60%, and a CuO concentration of 75 ppm, the BTE was determined to be 32% for the standard piston and 31. 1% for coated piston which slightly lower for alternative settings, thereby validating the statistical results.

Equation (4) for a Normal Piston and Eq. (5) for an (TBCs-YSZ) Coated Piston were derived from the RSM quadratic model of BSFC based on the measured parameters.

The BSFC Anova Table 9 show the impact of different variables—load (A), AOME blend (B), and CuO nanoparticle concentration (C)—on fuel efficiency for both normal and thermal barrier YSZ coated pistons. The model indicates that load has a positive coefficient (0.0457911) for the standard piston. Meanwhile, the AOME blend and CuO have negative coefficients (-0.092 and − 0.085, respectively), implying that an increase in blend percentage and CuO concentration generally results in a decrease in BSFC. The statistical significance of the combined effect of load and AOME blend on BSFC is indicated by the significant interaction term AB (0.14375), which has a p-value of 0.0485. The model’s F-value (1.91), while not statistically significant in its entirety (p = 0.1647), does underscore significant interactions and non-linear effects, specifically observed sum of square terms.

CuO nanoparticle concentration have varying impacts on fuel efficiency for both types of pistons, for the normal piston, load has a positive effect, while AOME blend and CuO concentration have negative effects, indicating that higher blend percentages and CuO concentrations lead to improved fuel efficiency. The significant interaction between load and AOME blend further underscores the importance of these factors in optimizing BSFC, as shown by the p-value of 0.0485.

The thermal barrier YSZ-coated piston exhibits distinct dynamics, as indicated by the coefficients: BSFC is negatively affected by load (A) (− 0.095), suggesting that an increase in load results in a reduction in fuel consumption. In contrast, the positive coefficient (0.106) of the AOME blend indicates that as blend percentages increase, so does BSFC. This may be attributed to the relatively inefficient combustion properties observed at higher blend levels. The significance of the squared term B2 (− 0.433182) on BSFC highlights the non-linear effect of the AOME composite. The absence of important interactions and individual factors, as indicated by the higher p values, suggests that the coated piston exhibits reduced sensitivity to changes in blend, load, and CuO concentration. This is reflected in the model’s overall F value of 0.8690 (p = 0.5787).

Figures 14 and 15 illustrate effects can be represented using 2D and 3D surface plots. 2D surface plot depicting the relationship between load and AOME blend at a constant CuO concentration may emphasise the significant AB interaction pertaining to the standard piston. A 3D surface plot can provide additional insight into the cumulative impact of the three factors on BSFC. Figure 16 Perturbation plots may offer supplementary insights regarding the degree of BSFC sensitivity to minute variations in each individual factor. As an illustration, the BSFC for the standard piston is 0.21% when operating at a load of 50 kg, an AOME blend of 40%, and a CuO concentration of 75 ppm; this value signifies enhanced fuel efficiency in the given conditions. On the different, when subjected to a load of 0 kg, an AOME blend of 20%, and a CuO concentration of 50 ppm, the thermal barrier YSZ coated piston exhibits a lesser consumption of 0.01% as indicated by the BSFC. The integration of visual and statistical analyses facilitates comprehension of the manner in which the various variables and their interrelationships influence the fuel consumption efficiency of both piston types.

Emission result

The CO emissions for both normal and thermal barrier YSZ coated pistons under different load (A), AOME blend percentage (B), and CuO nanoparticle concentration (C) conditions are clarified by the Eqs. (6) and (7). There is a statistically significant overall coincide with between the normal piston (F = 9.38, p = 0.0008). High F values (23.08 and 29.60) and low p values (0.0007 and 0.0003) indicate great statistical significance, highlighting the load (A) and CuO concentration (C) as the most influential factors. The squared terms and the interaction terms (AB, AC, and BC) similarly exhibit different degrees of influence, with the AC interaction standing out with a significant p value of 0.0022.

CO emission Anove Table 10 shows the additional, the model attempts to show a statistically significant overall fit (F value of 1.13, p value of 0.4221) for the piston covered with the thermal barrier YSZ. Even though they lack the same statistical impact as the normal piston, parameters like load (A) and CuO concentration (C) can contribute to emissions. An important factor is the elevated temperature inside the coated engine, which is a result of the thermal barrier YSZ. Because the coated engine operates at a higher temperature and the biodiesel has more oxygen available for combustion, the CO emissions are reduced. Coatings increase biodiesel evaporation and oxidation, which in turn decreases CO emissions, by retaining heat and decreasing heat loss to the coolant and exhaust.

The varying concentrations of CuO nanoparticles significantly impact carbon monoxide (CO) emissions for the normal piston, as shown by the low p-value (0.0003) for CuO in the ANOVA results, indicating a substantial effect. The normal piston shows a notable reduction in CO emissions as CuO concentration increases, which can be attributed to improved combustion efficiency due to CuO’s catalytic properties.

Figures 17 and 18 Surface plots in 2D and 3D dimensions can be developed to show these effects, at a constant CuO concentration, a 2D surface correspond can reveal the load-AOME blend interaction, increasing CO emission to important interactions like AC for the standard piston. The impact of each of these three variables on CO emissions can be shown in a 3D surface plot. The sensitivity of CO emissions to minute changes in each component can be further illustrated using perturbation graphs shown in Fig. 19. As an illustration, when subjected to the same conditions (i.e., a weight of 0 kg, an AOME mix of 20%, and a CuO concentration of 50 ppm, the CO emission for the normal piston is 0.005%, but it is 0.28% for the thermal barrier YSZ coated piston. The results suggest that the coated piston helps reduce CO emissions at higher operating temperatures by improving fuel combustion efficiency, but the conventional piston performs better consistently under all conditions.

Equation 8 for a Normal Piston and Eq. 9 for an (TBCs-YSZ) Coated Piston were derived from the RSM quadratic model of HC emission based on the measured parameters.

The analysis of hydrocarbon (HC) emissions from diesel engines using normal and thermal barrier YSZ coated pistons indicates the effect of load (A), AOME blend percentage (B), and CuO nanoparticle concentration (C) on emission levels. The Table 11 HC emission ANOVA results for the normal piston show that the parameters or their interactions had a significant effect on HC emissions, as showed by the high p-values (for example, Load: p = 0.6513, AOME Blend: p = 0.7257. The model’s F-value of 0.4210 and p-value of 0.8957 provide further validation, showing a lack of substantial fit. It is possibly due to the increased viscosity of biodiesel compared to diesel, which reduces combustion efficiency and increases HC emissions. In comparison, the model for the thermal barrier YSZ coated piston show a significant fit (F value of 0.2513, p value of 0.9753), but the individual components and their interactions react significantly. The coating absorbs heat within the combustion chamber, which improves the combustion process and reduces HC emissions when compared to an uncoated piston. The lower p-values for individual components like A (p = 0.5503) and interactions like AB (p = 0.3524) indicate that the coated engine’s enhanced combustion efficiency at different loads and blend ratios includes to the overall reduction in HC emissions.

The sources of HC emissions in diesel engines include wall quenching of fuel vaporising from the nozzle chamber volume during the last phases of combustion. The higher viscosity of biodiesel without coating causes poor combustion, resulting in higher HC emissions compared to diesel. However, the coated engine retains more heat within the combustion chamber, resulting in better fuel combustion and lower HC emissions across all loads. For example, with a load of 50 kg, a 40% AOME blend, and a CuO concentration of 100 ppm, the HC emission is 35 ppm for the normal piston.

The varying concentrations of CuO nanoparticles do not significantly influence hydrocarbon (HC) emissions in either the normal or YSZ-coated pistons, as indicated by the high p-values (greater than 0.05) for CuO in both models. For the normal piston, the interactions between load, AOME blend, and CuO concentration had minimal impact on HC emissions, likely due to biodiesel’s higher viscosity, which reduces combustion efficiency and increases HC emissions.

Figures 20 and 21 illustrating these impacts, 2D and 3D surface plots can be utilised. A 2D surface plot displaying the interplay of load and AOME mix at a constant CuO concentration can show how these variables affect HC emissions. A 3D surface plot will show the impacts of load, blend, and CuO concentration on HC emissions. Figure 22 shows the Perturbation plots can highlight the sensitivity of HC emissions to minor changes in each element, allowing for an in-depth comprehension of how each variable and their interactions effect emissions. For example, with a load of 50 kg, a 40% AOME mix, and a CuO concentration of 75 ppm, the HC emission for the coated piston is 37.5 ppm, showing the difference in emissions between normal and YSZ coated pistons under similar conditions.

Equation (10) for a Normal Piston and Eq. (11) for an (TBCs-YSZ) Coated Piston were derived from the RSM quadratic model of NoX emission based on the measured parameters.

For both normal and thermal barrier YSZ coated pistons, the Table 12 ANOVA NoX emissions can be analysed according to load (A), AOME blend (B), and CuO nanoparticle concentration (C). This allows us to understand the combustion dynamics better. With an F value of 0.2871 and a p value of 0.9630, the model shows a increasing for the normal piston, indicating that the variables and their interactions have a substantial impact on NOx emissions. The low impact of individual components on NOx emissions is shown by the high p values of load (p = 0.7636), AOME mix (p = 0.6705), and CuO concentration (p = 0.7713). Additionally, the squared terms interaction term AB (p = 0.2674) make statistically important contributions. This indicates that the normal piston’s NOx emission levels are unaffected by changes to these parameters.

The thermal barrier YSZ coated piston model, on the opposite, performs marginally better (F = 0.4173, p = 0.8999) but still reach statistical significance. Low p values for individual components compared to the normal piston suggest that they have a minor influence on NOx emissions; for example, AOME mix (p = 0.5681) and CuO content (p = 0.5894). Nox emissions are also slightly affected by the squared terms p = 0.4965 and the interaction terms AB with p = 0.3515. While the thermal barrier YSZ coating may improve combustion efficiency by keeping heating in the chamber, it also raises the peak flame temperature, which in turn increases NOx emissions because of the thermal NOx production principle.

The presence of CuO in both normal and thermal barrier YSZ coated pistons has minimal impact on NOx emissions, as indicated by the high p-values for individual factors (CuO: p = 0.7713 for normal and p = 0.5894 for coated pistons). The thermal barrier coating improves combustion efficiency but also raises peak flame temperatures, which increases NOx emissions due to thermal NOx production. However, the overall effect of CuO and other factors on NOx emissions remains limited.

The presence of additional oxygen in the combustion chamber and the peak flame temperature are the main factors that cause NOx emissions to be formed. While biodiesels like AOME have inherent oxygen that improves combustion, the higher combustion temperatures also increase NOx emissions. Due to these reasons, numerous studies have shown that biodiesel fuels typically emit more nitrogen oxides (NOx) than diesel. The Perturbation shown in Fig. 25 Take the standard piston as an example; it emits 258 ppm of NOx under 50 kg of load, 40% AOME mix, and 75 ppm CuO concentration. In contrast, the NOx emission for the thermal barrier YSZ coated piston increases to 363.6 ppm under no load, 20% AOME mix, and 100 ppm CuO, indicating higher combustion efficiency and peak temperatures made possible by the coating.

Figures 23 and 24 Surface plots in 2D and 3D can be created to illustrate these effects. To show the influence of load and AOME blend on NOx emissions at a constant CuO concentration, a 2D surface plot might be generated. To better understand the interplay of these three variables, a 3D surface plot is appropriate. However, the NOx emissions change in response to small changes in each variable by looking at a perturbation plot. In a 2D plot, NOx emissions are seen to rise as AOME mixes and loads are increased, but in a 3D plot, the complex relationship between these three variables can be seen, and areas with higher emissions may be identified. Diesel engines with standard and thermal barrier YSZ coated pistons can have their complex dynamics of NOx emission better understood with the use of these graphical tools when combined with statistical analyses (Fig. 25).

Equation (12) for a Normal Piston and Eq. (13) for an (TBCs-YSZ) Coated Piston were derived from the RSM quadratic model of NoX emission based on the measured parameters.

Table 13 shows the the analysis of smoke density, an important factor for determining engine emissions, gives us indications both normal and thermal barrier YSZ coated pistons burn fuel. It’s an average fit for the standard piston model, with an F value of 1.77 and a p value of 0.1929. However, high p values for all variables show that none of the factors or their relationships have significant impacts on smoke density. It looks like load (A), AOME mix (B), and CuO concentration (C) have a big effect on smoke emissions for the normal piston because they don’t change them significantly. The model for the thermal barrier YSZ covered piston, on the opposite, with an F value of 0.6461 and a p value of 0.7384. Some factors, like load (A) for the regular piston and CuO concentration (C) for the coated piston, have slightly lower p values. This means they might have some effect on smoke density.

The main cause of smoke density in automotive engines is fuels that don’t burn all the way. Because biodiesel mixes contain extra oxygen particles that help the fuel burn more completely, they tend to have a positive effect on smoke emissions. Putting a covering on the inside of the cylinder wall improves combustion efficiency by raising the temperature of the gas, which makes the smoke much less dense. For instance, a normal piston gives off 3.8 BSU of smoke when it is loaded with 50 kg, the AOME blend is 40%, and the CuO concentration is 75 ppm. With a load of 100 kg, an AOME mix of 60%, and a CuO concentration of 50 ppm, on the opposite the thermal barrier YSZ coated piston gives 6.66 BSU less smoke. These results show that both biodiesel blends and thermal barrier YSZ coatings might help cut down on smoke pollution and make combustion more efficient overall.

Biodiesel blends improve combustion efficiency and reduce smoke density due to their higher oxygen content, which promotes more complete fuel combustion and reduces unburned hydrocarbons that cause smoke. The thermal barrier YSZ coating further enhances combustion by increasing gas temperatures inside the cylinder, leading to better fuel atomization and burning. The combination of biodiesel blends and thermal coatings significantly reduces smoke density, as evidenced by lower emissions, particularly under higher loads and blend concentrations.

Figures 26 and 28 shows the Visualisations like 2D and 3D surface plots can help us learn more about how load, AOME blend, CuO concentration, and smoke releases are connected. You can also use Fig. 27 perturbation plots to show how sensitive smoke emissions are to small changes in each factor. Even though the statistical studies may not show much of an effect, the real-world effects of lower smoke density make it clear that it is to improve the environmental and performance benefits of combustion processes in automobile engines. Figure 27 shows that Smoke emission 3D Plot – (a) Piston (Normal) (b) Piston (TBCs/YSZ Coated).

Conclusions

The utilisation of the RSM optimisation technique shown its effectiveness in examining the impact of load, Algae oil Methyl Ester (AOME), and CuO injection with normal and thermal barrier YSZ coating on engine performance and exhaust emission concluded (Fig. 28).

-

Thermal barrier coatings, specifically YSZ, in combination with biodiesel blends, improved engine performance and emission reduction, and also reduction in smoke density compared to the normal piston under high load conditions.

-

Biodiesel blends achieved performance and emission characteristics comparable to pure diesel, with a minor decrease in BTE of about 3–5%. However, higher CuO concentrations enhanced combustion efficiency but slightly reduced BTE compared to diesel.

-

When CuO is utilised as a fuel in conjunction with a glow plug, it reduces the emission of pollutants from the exhaust. But it led to decreased efficiency in comparison to diesel fuel.

-

CuO nanoparticles, when used as a fuel additive, significantly reduced emissions of CO and HC. However, the combination of CuO with delayed injection timing led to elevated NOx emissions due to increased combustion temperatures.

-

The low heat rejection engine equipped with partially stabilized TBC-YSZ coatings exhibited superior thermal efficiency, with approximately a 10% improvement over normal pistons.

Future scope

Future research should explore advanced thermal barrier materials beyond YSZ to further minimize NOx emissions while maintaining thermal efficiency. Additionally, investigating the synergistic effects of various nanoparticles or oxygenated additives in biodiesel blends could help optimize performance and emissions trade-offs. Developing adaptive injection timing strategies may provide a viable solution to reduce NOx emissions while enhancing combustion efficiency. Furthermore, expanding RSM-based optimization studies to assess the long-term durability and economic feasibility of TBC-YSZ-coated pistons in real-world applications will be essential for their practical implementation.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bharadwaz, Y. D., Rao, B. G., Rao, V. D. & Anusha, C. Improvement of biodiesel methanol blends performance in a variable compression ratio engine using response surface methodology. Alex. Eng. J. 55 (2), 1201–1209 (2016).

Papu, N. H., Lingfa, P. & Dash, S. K. Euglena Sanguinea algal biodiesel and its various diesel blends as diesel engine fuels: a study on the performance and emission characteristics. Energy sour. Part A recovery util. Energy Sour. Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2020.1798566 (2020).

Ranjit, P. S. & Chintala, V. Impact of liquid fuel injection timings on gaseous hydrogen supplemented-preheated straight vegetable oil (SVO) operated compression ignition engine. Energy Sour. Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2020.1745333 (2020).

Suresh, A., Babu, A. V., Balaji, B. & Ranjit, P. S. Experimental investigation of NOx emission control using carbon nanotube additives and EGR configuration on CRDI engine fueled with ternary fuel. Biofuels 15 (10), 1315–1329. https://doi.org/10.1080/17597269.2024.2366446 (2024).

Balamurugan, M., Dhairiyasamy, R., Bunpheng, W., Kit, C. C. & Gabiriel, D. Enhanced performance and reduced emissions in LHR engines using Albizia lebbeck antioxidant-infused SBME20 biodiesel. Ind. Crops Prod. 222 (119677), 119677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.119677 (2024).

Saxena, V., Kumar, N. & Saxena, V. K. Multi-objective optimization of modified nanofluid fuel blends at different TiO2 nanoparticle concentration in diesel engine: experimental assessment and modeling. Appl. Energy. 248, 330–353 (2019).

Bernardo, A., Boeris, D., Evins, A. I., Anichini, G. & Stieg, P. E. A combined dual-port endoscope-assisted pre-and retrosigmoid approach to the cerebellopontine angle: an extensive anatomo-surgical study. Neurosurg. Rev. 37, 597–608 (2014).

Rajpoot, A. et al. Exploring the potential and progress of microalgae biomass production, harvesting, and pre-treatment for sustainable biofuel production: a comprehensive review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 15 1–51. (2025).

Venkatesh, A. P. et al. Multiparametric optimization on influence of ethanol and biodiesel blends on nanocoated engine by full factorial design. J. Nanomater. 2022 1–12 (2022).

Prakash, S., Prabhahar, M., Niyas, O., Faris, S. & Vyshnav, C. Thermal barrier coating on IC engine piston to improve efficiency using dual fuel. Mater. Today Proc. 33, 919–924 (2020).

Rajpoot, A. et al. Comparison of the effect of CeO2 and CuO2 nanoparticles on performance and emission of a diesel engine fueled with Neochloris oleoabundans algae biodiesel. Mater. Today Proc. 102 : 59–64. (2024).

Khoobbakht, G. et al. Optimization of operating factors and blended levels of diesel, biodiesel and ethanol fuels to minimize exhaust emissions of diesel engine using response surface methodology. Appl. Therm. Eng. 99, 1006–1017 (2016).

Kalyani, T., Prasad, L. S. V. & Kolakoti, A. Biodiesel production from a naturally grown green algae Spirogyra using heterogeneous catalyst: an approach to RSM optimization technique. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 12 (2), 300 (2023).

Rajpoot, A. et al. An experimental study of the impact of manganese dioxide (MnO2) blended fuel on the performance and emission characteristics of a diesel engine. The International Conference on Sustainable Energy Technologies (Springer Nature, Singapore, 2023).

Ananthi, V. et al. A critical review on different harvesting techniques for algal based biodiesel production. Sci. Total Environ. 780, 146467 (2021).

Chozhavendhan, S., Pradhap Singh, V., Fransila, M., Kumar, B. P. & Devi, K. R., G. A review on influencing parameters of biodiesel production and purification processes. Curr. Res. Green. Sustain. Chem. 1–2(April), (2020). 1 6.

Manickam, S., Pachamuthu, S. & Chavan, S. Effect of thermal barrier coatings on the stability, performance, and emission characteristics of Pongamia water emulsion biodiesel in ci engines. Performance, and emission characteristics of Pongamia water emulsion biodiesel in ci engines.

Anjaneya, G. et al. Performance analysis and optimization of thermal barrier coated piston diesel engine fuelled with biodiesel using RSM. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 57, 104351 (2024).

Robert Vaben, M. O., Jarligo, T., Steinke, D. E. & Mack Detlev Stover, overview on advanced thermal barrier coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 205, 938–942 (2010).

Kiilakoski, J. Damage tolerance of thermally sprayed oxide coatings. (2020).

Ozgurluk, Y., Karaoglanli, A. C. & Ahlatci, H. Comparison of calcium–magnesium-alumina-silicate (CMAS) resistance behavior of produced with electron beam physical vapor deposition (EB-PVD) method YSZ and Gd2Zr2O7/YSZ thermal barrier coatings systems. Vacuum 194, 110576 (2021).

Bertrand, G., Bertrand, P., Roy, P., Rio, C. & Mevrel, R. Low conductivity plasma sprayed thermal barrier coating using Hollow Psz spheres: correlation between thermophysical properties and microstructure. Surf. Coat. Technol. 202 (10), 1994–2001 (2008).

Prokip, V. E., Lozanov, V. V., Bannykh, D. A., Morozova, N. B. & Baklanova, N. I. Preparation of zirconia coatings on silicon carbide fiber by metal organic chemical vapor deposition. Inorg. Mater. 57, 269–274 (2021).

Huang, J. et al. Achieving high anti-sintering performance of plasma-sprayed YSZ thermal barrier coatings through pore structure design. Surf. Coat. Technol. 435, 128259 (2022).

Karaoglanli, A. C., Doleker, K. M. & Ozgurluk, Y. Interface failure behavior of Yttria stabilized zirconia (YSZ), La2Zr2O7, Gd2Zr2O7, YSZ/La2Zr2O7 and YSZ/Gd2Zr2O7 thermal barrier coatings (TBCs) in thermal Cyclic exposure. Mater. Charact. 159, 110072 (2020).

Mahade, S. et al. Functional performance of Gd2Zr2O7/YSZ multi-layered thermal barrier coatings deposited by suspension plasma spray. Surf. Coat. Technol. 318, 208–216 (2017).

Ganvir, A., Curry, N., Markocsan, N., Nylén, P. & Toma, F. L. Comparative study of suspension plasma sprayed and suspension high velocity oxy-fuel sprayed YSZ thermal barrier coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 268, 70–76 (2015).

Chavez, J. J. G. CMAS/volcanic ash infiltration performance of yttria rich-zirconia thermal barrier coatings produced by electron beam physical vapor deposition (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Texas at El Paso). (2019).

Bolelli, G. et al. Tribological properties of plasma sprayed Cr2O3, Cr2O3–TiO2, Cr2O3–Al2O3 and Cr2O3–ZrO2 coatings. Wear 480, 203931 (2021).

Zambrano, D. F. et al. Thermal properties and phase stability of Yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) coating deposited by air plasma spray onto a Ni-base superalloy. Ceram. Int. 44 (4), 3625–3635 (2018).

Garcia, E., Mesquita-Guimaraes, J., Osendi, M. I. & Miranzo, P. Thermal conductivity in mullite/ZrO2 composite coatings. Ceram. Int. 36 (5), 1609–1614 (2010).

Daroonparvar, M. et al. Surface modification of magnesium alloys using thermal and solid-state cold spray processes: challenges and latest progresses. J. Magnes. Alloys. 10 (8), 2025–2061 (2022).

Lugschedier, E. & Kvernes, I. Thermal barrier coatings: powder spray process and coating technology. Mater. Eng. N Y. 13, 267–306 (1999).

Xu, Z. et al. Double-ceramic-layer thermal barrier coatings of La2Zr2O7/YSZ deposited by electron beam-physical vapor deposition. J. Alloys Compd. 473 (1–2), 509–515 (2009).

Bitire, S. O., Nwanna, E. C. & Jen, T. C. The impact of CuO nanoparticles as fuel additives in biodiesel-blend fuelled diesel engine: a review. Energy Environ. 34 (7), 2259–2289 (2023).

Ağbulut, Ü. et al. Effects of high-dosage copper oxide nanoparticles addition in diesel fuel on engine characteristics. Energy 229, 120611 (2021).

Khidr, M. E., Megahed, T. F., Ookawara, S. & Elwardany, A. E. Effects of aluminum and copper oxides nanoparticles as fuel additives on diesel engine operating characteristics. Atmos. Pollut Res. 14 (4), 101721 (2023).

Perumal, V. & Ilangkumaran, M. The influence of copper oxide nano particle added pongamia Methyl ester biodiesel on the performance, combustion and emission of a diesel engine. Fuel 232, 791–802 (2018).

D’Silva, R. et al. Effect of Copperoxide nanoadditives on the performance and emissions characteristics of a CI engine. Energy Power. 7 (4), 99–104 (2017).

Surendrababu, K. et al. Performance, emission, and study of DI diesel engine running on pumpkin seed oil Methyl ester with the effect of copper oxide nanoparticles as an additive. J. Nanomater. 2022, 1–9 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.P, S.P—Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing Original Draft, Visualization and Data Curation, P.D, E.P.V, F.X—Visualization and Supported for data interpretation, N.H, M.P Writing Original Draft, Visualization and Data Curation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Prabhahar, M., Prakash, S., Dharsan, P. et al. Optimization of thermal barrier coating with induced copper oxide nanoparticles in CI engine using algae methyl ester as fuel. Sci Rep 15, 21221 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02711-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02711-7