Abstract

Well-designed guidance of the magnetic field through electric steel sheets forming the rotor of electrical motors and generators is of utmost importance with regards to efficiency. Typically, this is achieved through tailored cutouts in the sheets. While fulfilling the magnetic guidance needs this strategy structurally weakens the rotor and ultimately limits the possible rotation speeds due to the mechanical forces these imply. Recently an alternative approach has been reported, in which the material is embossed in respective regions. The, thus, induced stresses act, based on the inverse magnetostrictive effect, as flux barriers without, unlike traditional cutouts, weakening the structure significantly. Here we propose to replace the embossing through laser shock peening, which can be controlled digitally and hence be applied flexibly, without the need for mechanical changes in the production lines, like in the case of a punch.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

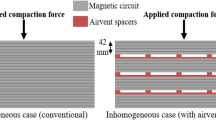

The current trend and environmental relevance of electric vehicles create a growing demand for highly efficient electromobility and electric machinery in general. Efficiency for rotating electrical machines implies foremost to optimize magnetic flux and avoid stray flux related losses. This can be achieved by well-designed magnetic flux guidance which thus is of utmost importance for e.g. synchronous reluctance machines and permanent magnet synchronous machines1,2. To date such flux guidance is achieved through specifically designed holes in the rotor fabricated of non-grain oriented electric steel sheets3. This means the electric steel sheets are cut into the desired shapes before assembling the rotor from the sheet material. While the cutouts function as flux barriers, they weaken the structure of the rotor which has to withstand high centrifugal forces during high frequency rotation. This in turn limits the maximum rotation speed that can be reached and therefore decreases the best energy density and efficiency that can be achieved4,5. Recently a novel approach has been demonstrated aiming to overcome these competing influences on the efficiency of electric engines. In this approach the cutouts are replaced by corresponding embossing patterns, which imply compressive stresses in treated areas. According to the magneto-mechanical Villari effect6,7 these stresses pin the magnetic domains, which leads to a reduced magnetic permeability in the worked area of the NGO sheet material8,9,10. This way flux barriers of desired shapes can be created without the detrimental weakening effect on the rotor, which is implied by cutouts. This consequently has a significant potential to further increase the efficiency of electric machinery.

Here we present an alternative approach towards generating flux barriers based on the inverse magnetostrictive effect, namely through applying laser shock peening (LSP) instead of a mechanical punch. This process can be fully controlled digitally and can be integrated with laser cutting11, laser scribing12 and laser healing13 in a future advanced digital manufacturing process of high efficiency electric machinery. In addition, it can also be applied to the thin side of the electric steel laminates, with the aim to reduce magnetic conductivity in the leakage web between the tooth tips in induction machines with closed rotor slots. In order to demonstrate the effect of laser shock peening and thus the feasibility of the approach we apply neutron grating interferometry to visualize the local effect of the process. This approach is in accordance with earlier works on the effect of different cutting and laser techniques on the local magnetic domain structure and permeability of electric steels11,12,13 but also the works on embossing to create magnetic flux barriers10,14.

Experimental

Samples and sample treatment

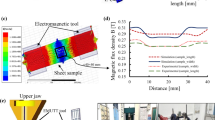

The samples are 300 micrometer thick non-grain oriented (NGO) electric steel (280-30AP) lamination sheets. These sheets are coated with glassy magnesium silicate. From the as received 30 mm x 300 mm sheets pieces of 30 mm x 60 mm were cut for LSP treatments. Rectangular central regions of about 15 mm x 15 mm of nine 30 mm x 60 mm pieces were LSP treated with different parameters, including laser energies from 0.5 to 1.5 J, at pulse frequencies of 5–10 Hz and with or without the use of a protective sacrificial aluminum layer. The spot overlap of the LSP procedure was 40%. Some selected samples (#2,#3,#5,#8 and #9) were additionally treated from the side, i.e. on the 300 micrometer thick edge. These treatments were done with 1.5 J and 10 Hz. A list of the samples as well as corresponding images are shown in Table 1; Fig. 1, respectively.

Measurements

Dark-field contrast measurements15,16,17 were performed at the BOA beamline at the SINQ neutron source of the Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland18. Dark-field contrast imaging is sensitive to small angle neutron scattering in the ultra-small and very-small angle regime, i.e. for scattering from structures in a size range from some 10 nm to some 10 micrometers, depending on the applied set-up and parameters. A symmetric Talbot Lau grating interferometer19 was employed for the measurements and the samples where mounted in an electromagnetic yoke with tunable applied field. Dark-field contrast is generated by the effect of magnetic domains on the refractive index of neutrons, respective by their contribution to the scattering length density contrast. These contributions are opposite for spin-up and spin-down neutrons16. Thus, the neutron dark-field contrast is sensitive to the domain wall density in the material and the respective magnetisation. According to the magnetomechanical effect the induced stress in the material increases the magnetic anisotropy and domain wall density. This directly affects the magnetic permeability and the dark-field contrast, which increases correspondingly as the permeability is decreasing. This has been used in numerous studies to investigate the local effect of stress on the magnetic permeability10,11,12,13,14,20, e.g. at cutting edges with respect to different cutting processes, but also with regards to the creation of artificial flux barriers through intentionally induced stresses.

(A) photograph of NGO electric steel sheet samples #1 - #9 after LSP treatment; note that the red frames mark LSP treatments done in TD onto the slim side of the sheets; sample #2 features a hole due to high energy laser LSP treatment, sample #7 has three different treatments, of which only two are considered successful and the treatment of sample #8 conveys a smaller area; (B) corresponding dark-field contrast neutron images displaying most treated regions; note also the visibility of the side treatments in areas corresponding to the red frames in (A).

Samples have been measured in two configurations, with the magnetic field applied in vertical direction, i.e. perpendicular to the scattering sensitivity of the Talbot Lau grating interferometer, and with the magnetic field applied horizontally, perpendicular to the grating lines. As the samples were rotated together with the magnetic yoke, the field was always applied in the same direction with respect to the NGO steel sheet, i.e. in rolling direction (RD).

This implies that when the sample is oriented with RD vertical, domain density in transversal direction (TD) is probed, and when RD is horizontal, domain density along RD is probed. While all samples have been screened with dark-field contrast imaging (Fig. 1) some selected samples, namely samples #5 and #7 (a, b) as well as an untreated reference have been exposed to step-wise hysteretic magnetization. This was done in the neutron imaging instrument with a yoke installed in the sample position and enabled to record corresponding dark-field contrast image series in analogy to other similar reported investigations of stress-affected NGO steel sheets14. The applied magnetic fields correspond to 0, 1500, 3000 and 4500 A/m.

Results

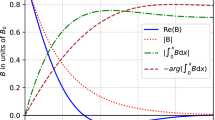

The measurement of the untreated reference sample reveals an anisotropy in the magnetic domain structure, and thus of the material. This is typically found in NGO steels due to anisotropic production conditions21,22. The results (Fig. 2) suggest that the domain wall density is higher in TD of the NGO strip (Fig. 2A & B), than in RD, i.e. the longer direction (Fig. 2C & D). The relative response to the applied field is, however, comparable and is showing a decrease in dark field contrast (increasing dark-field values) of about 20% in both cases for an applied field of 4500 A/m.

The measurement of sample #5 clearly displays the effect of the LSP with considerably increased dark field contrast in the treated area, as is expected from domain pinning due to residual stresses and deformation (Fig. 3). Note that the green rectangles in Fig. 3A and C denote the region of the line profile impacted by the side treatments with LSP, which are all clearly visible in the dark-field images (Fig. 3E & F). The red rectangles on the other hand mark an area where the electric steel sheet is not fully contacted with the yoke for geometrical reasons. This artefact can be ignored to a first approximation and impacts the results insofar as a certain asymmetry can be observed in the dark-field profiles and in particular under the applied magnetic field condition.

Sample #5: A and B show the transverse (TD) dark-field profiles across the electric steel sheet #5 for the vertical and horizontal RD/field orientation measurement, respectively, and respective reference profiles of the untreated steel sheet sample. C and D show respective profiles along the RD of the steel strip for the two field orientations, respectively, and E and F show the corresponding dark-field contrast images.

A comparison of the 4 types of dark-field contrast profiles presented in Fig. 3 alongside with the reference profiles of the untreated sample under the respective same conditions reveal some remarkable details. When first comparing the TD profiles for the vertical and horizontal sample RD/field orientation given in Fig. 3A and B, respectively, significant differences are observed. This is in particular the case for the region adjacent to the treated area. While both cases reveal a nearly constant dark-field contrast with respect to measurements with and without applied field in the treated area, the adjacent regions differ significantly. These seem to be unaffected with regards to the TD domain wall density (Fig. 3A), where these regions behave very similar to the untreated sample, but appear strongly affected with regards to the RD domain wall density, i.e. along the field direction (Fig. 3B). In the latter case the dark-field signal reaches values comparable to the 4500 A/m applied field case already without applied field, in particular where the sample is additionally affected by the side treatment. At the applied field of 4500 A/m the values reach those of the untreated sample in both cases. Notably a similar effect is observed for the opposite direction, where the regions in front and behind the treated area with respect to the field direction (Fig. 3C). Here the domain wall density across the strip (TD), i.e. perpendicular to the field direction appears to be reduced already before applying an external magnetic field.

Along the strip (RD) it is seen (Fig. 3D), on the other hand, that at maximum applied field of 4500 A/m the dark field values do not reach the level of that of the reference sample, implying a remaining higher domain wall density in RD and, thus, field direction in this case as compared to the untreated reference. This appears again to be related to the flux barrier, which reduces the magnetic flux in this direction in that area, as is part of the desired effect of the treatment. Comparable trends to those described here for sample #5 can be found for treated areas in other samples of the measurement series, and these align well with dark-field imaging results for embossing treatments23.

Sample #7 features two LSP treated areas that differ in the laser power used, which was 1.5 J for the area #7a and 1 J for the area 7b (Fig. 4). In Fig. 4A we compare the response of the treated areas to increasing applied external fields. It becomes obvious, that the treatment with the higher laser power (#7a) is more sustainable in resisting the applied field than the area (#7b) treated with two thirds of the laser power, i.e. 1 J. When comparing with sample #5 which has been treated with only 0.5 J but 10 Hz, in contrast to 5 Hz in the sample #7 treatments, one finds sample 5 would range between sample #7a and #7b.

Sample#7: (A) Neutron dark-field contrast in the two treated areas, as indicated in (B), for increasing applied external magnetic fields; (B) dark-field contrast image of the sheet and a detail including the signature of two side treatments; (C) dark-field contrast line profiles at the position indicated in (B) for different applied external magnetic fields in a hysteresis scan;

Sample#7 also features treatments from the side which are clearly visible in Fig. 4B at the right side of the #7b treatment area at the edge of the NGO electric steel sheet. These treatments leave traces of their effect in the dark-field contrast image for at least 5 mm into the sheet area. The enlarged detail in Fig. 4B reveals a complex pattern around needle like straight and fading signatures. To the sides a V-shaped region of less dark-field contrast, comparable to a non-affected sheet are found, and subsequently in the triangular regions next/below the V darker, i.e. more affected areas. Figure 4C displays slight differences between the two side treatments in line profiles indicated in the detail in Fig. 4B by a black line. The upper treatment appears to have a stronger and more sustainable effect. At this stage it cannot be concluded whether this is due to the accuracy of the treatments, which were in principle done with the same parameters, or whether the relation to the treated areas on the surface have an impact.

Discussion

We applied laser shock peening to NGO electric steel sheets and could demonstrate, utilizing neutron dark-field contrast imaging, the effect and success of the treatments. Neutron dark-field contrast imaging has been established in recent years for corresponding spatially resolved observations of magnetisation, domain structure and domain pinning. Here it clearly shows that the induced stresses through the laser treatment deteriorate the domain structure similar to mechanical punching treatments and, thus affects the local magnetic permeability. In contrast we found through EBSD that the microstructure of the electric steel sheets is not affected, i.e. not noticeable altered, by the successful treatments. In addition we find that sheets treated with same parameters display coinciding results, which implies repeatability. In analogy to the mechanical punching approach the LSP treatment, thus, appears promising in guiding magnetic flux around such treated areas, which can replace the currently dominating approach of material cut-outs in laminates of electrical machinery. In contrast to such, the here demonstrated treatments can avoid the mechanical weakening of the material, as no cut-outs are necessary. Therefore, the approach can be a promising route for processing aiming at high performance electric motors. One can envision a laser-based manufacturing line, where lasers cut the required shapes, repair unwanted domain deterioration e.g. from cutting and induce stressed areas for magnetic field guidance, as proposed here etc. The advantage is a flexible programable digitally controlled process.

We acknowledge that the presented work is a mere individual first attempt in this direction, and many issues have to be addressed still. In the context of the here proposed laser shock peening treatments a prevailing issue appears to be the obvious damage to the isolating coating of the electric steel material. This might be avoided in an optimized laser shock peening process, which is beyond the scope of the current work introducing the mere potential of such treatments and a method to characterize its effects with the required spatial image resolution.

Methods

Dark-Field contrast imaging

Dark-field contrast imaging was performed at the BOA beamline18 at the SINQ neutron source of the Laboratory of Neutron Scattering and Imaging at the Paul Scherrer Institut in Switzerland. The utilized symmetric Talbot Lau interferometer consisted of three gratings. A source grating (G0), a phase grating (G1) and an analyser grating (G2). All gratings have a period of 25 μm. G0 and G1 are absorption gratings consisting of Gd lines with a thickness of 20 μm on a quartz waver with 100 mm diameter. G1 is a Si phase grating inducing a π/2 phase shift through a line height of 43.8 μm. This implies that the grating interferometer is optimised for a wavelength of 3.5 Å, while a cold neutron spectrum with a Maxwellian distribution with a peak at 2.8 Å and a weighted mean at 3.8 Å was applied. The distance between gratings is about 44.6 cm, which corresponds for G1 to G2 to the first fractional Talbot distance, considering a magnification factor M = 2. Dark-field measurements consist of phase stepping scans15 and 13 phase steps over one period were accounted for. Every step was recorded taking three images which were subsequently reduced through median filtering to single images per step. From these images the dark-field contrast image was calculated. The dark-field contrast image evaluates the modulation amplitude in each pixel with regards to the phase scan normalized to the modulation offset, i.e. the transmission image. These images V(x, y) are normalised to the open beam visibility V0(x, y) which ranges on pixel average at about 28%.

A PSI midibox detector24 was utilized featuring a LiFZnS(Ag) scintillator screen (from RC Tritec AG, Switzerland) with a thickness of 100 μm from RC Tritec, a Zeiss MAKRO-PLANAR 2/100 mm ZF.2 objective lens and an ANDOR-iKon-M CCD camera. The instrument pinhole was set to 20 × 20 mm2 and was 6.5 m upstream of the sample position. The exposure time per image was 30 s, leading to a total exposure per dark-field contrast image of about 20 min. All images were background and dose corrected.

Data availability

Raw data files used to produce the figures and tables in this report is available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Trancho, E. et al. PM-assisted synchronousreluctance machine flux weakening control for EV and HEV applications. IEEE Trans. Indus Electron. 65 (4), 2986–2995 (2018).

Juergens, J. et al. Innovative design of an air cooled ferritepermanent magnet assisted synchronous reluctance machine for automotive traction application. In: 2016 XXII InternationalConference on Electrical Machines (ICEM), pp. 803–810 2. (2016).

Jung, J. W. et al. Mechanical stress reduction of rotor core ofinterior permanent magnet synchronous motor. IEEE Trans. Magn. 48 (2), 911–914 (2012).

Gerada, D. et al. High-speed electrical machines: Technolo-gies, trends, and developments. IEEE Trans. Indus Electron. 61 (6), 2946–2959 (2013).

Chiodetto, N., Mecrow, B., Wrobel, R. & Lisle, T. Electro-mechanical challenges in the design of a high-speed-high-power-PMSM rotor for an aerospace application. In: 2019 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), pp. 3944–3951 (2019).

Villari, E. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 126, 87 (1865).

Salach, J., Szewczyk, R., Bienkowski, A. & Frydrych, P. Methodology of testing the magnetoelastic characteristics of ring-shaped cores under uniform compressive and tensile stresses (PDF). J. Electr. Eng. 61 (7), 93 (2010).

Bordin, G., Buttino, Cecchetti, A. & Poppi, M. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 150, 363 ; (1995).

Szewczyk, R., Bienkowski, A. & Salach, J. Fazakas, L. K. Varga. J. Optoelectron. Adv. M. 5, 705 (2003).

Schauerte, B. et al. The influence of residual stress on flux-barriers of non-oriented electrical steel. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 504, 166659 (2020).

Baumann, R., Siebert, R., Herwig, P., Wetzig, A. & Beyer, E. : Laser remote cutting and surface treatment in manufacturing electrical machines—High productivity, flexibility, and perfect magnetic performance. Journal of Laser Applications 27 (S2), S28002. (2015). https://doi.org/10.2351/1.4906383

Rauscher, P. et al. The influence of laser scribing on magnetic domain formation in grain oriented electrical steel visualized by directional neutron dark-field imaging. Sci. Rep. 6, 38307 (2016).

Siebert, R. et al. : Laser manufacturing of electrical machines. In: 2014. 2014 4th International Electric Drives Production Conference (EDPC). Nuremberg, Germany, 30.09.2014–01.10.2014: IEEE, S. 1–5; Siebert, Rene: Verfahren zur lokal gezielten Beeinflussung des magnetischen Flusses an Bauteilen aus einem weichmagnetischen Werkstoff und ein mit dem Verfahren hergestelltes Bauteil. DE102013002976 B4 (2014)–2014.

Vogt, S. et al. Extent of embossing-related residual stress on the magnetic properties evaluated using neutron grating interferometry and single sheet test. Prod. Eng. 13 (2), 211–217 (2019).

Strobl, M. et al. Neutron dark-field tomography. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 123902 (2008).

Valsecchi, J. et al. Decomposing magnetic dark-field contrast in spin analyzed Talbot-Lau interferometry - a Stern-Gerlach experiment without Spatial beam splitting. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 070401 (2021).

Strobl, M., Harti, R. P., Grünzweig, C., Woracek, R. & Plomp, J. Small Angle Scattering Neutron Imaging—A Rev. J. Imaging 3 64 (2018).

Morgano, M. et al. Neutron imaging options at the BOA beamline at Paul Scherrer Institut. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment, 2014. 754: pp. 46–56.

Kim, Y., Valsecchi, J., Kim, J., Wook Lee, S. & Strobl, M. Symmetric Talbot-Lau neutron grating interferometry and incoherent scattering correction for quantitative dark-field imaging. Sci. Rep. 9, 18973 (2019).

René & Siebert Bestimmung der magnetischen Flussdichteverteilung in nichtkornorientiertem Elektroblech nach dem Laserschneiden mittels Neutronen-Dunkelfeld-Bildgebung, Berichte aus der Lasertechnik, Shaker Verlag, Aachen, : 9783844039566, (2015). ISBN https://doi.org/10.2370/9783844039566

Kurosaki, M. S. Y. Anisotropy of magnetic properties in Non-oriented electrical steel sheets. Texture Stress Microstruct. 11 (2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1155/TSM.11.159 (1989).

Chwastek, K. Anisotropic properties of non-oriented steel sheets. IET Electr. Power Appl. 7, 575–579. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-epa.2013.0087 (2013).

Neuwirth, T. et al. A high visibility Talbot-Lau neutron grating interferometer to investigate stress-induced magnetic degradation in electrical steel. Sci. Rep. 10, 1764. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58504-7 (2020).

Lehmann, E., Trtik, P. & Ridikas, D. Status and perspectives of neutron imaging facilities. Phys. Procedia. 88, 140–114 (2017).

Acknowledgements

JZ and MS acknowledge the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) for funding this research under grant agreement No. 200021_197048. The authors thank R. Loge and N. Kalentics at the Thermomechanical Metallurgy Lab – PX Group Chair, Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland, for their support with the laser shock peening.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JZ and MS conceived the experiments. MS conceived the methodical approach. JZ, MB and MS analysed the data. JZ, JV, M.B. and GN conducted the experiments. PR provided the material and supported the experiments and analyses. JZ and MS wrote the initial manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shen, J., Busi, M., Rauscher, P. et al. A neutron dark-field imaging study towards guiding magnetic flux in electric steel sheets through laser shock peening. Sci Rep 15, 18438 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02806-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02806-1