Abstract

Solid state reaction method is most commonly used to synthesize Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ phosphors. In order to avoid the energy waste caused by high sintering temperature, we systematically studied and optimized the preparation process of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ long afterglow phosphors by increasing the Si/Sr ratio in the raw materials. The appropriate addition of silica not only facilitates the preparation of single phase Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ phosphor but also enhances the rate of solid state reaction, so as to achieve the purpose of reducing the sintering temperature. The photoluminescence performance of the sample with a Si/Sr ratio of 1.1 sintered at 1350 °C is the highest, followed by that of the sample sintered at 1400 °C with a Si/Sr ratio of 1.0. Notably, the photoluminescence properties of the Si/Sr ratio of 1.3 sample sintered at 1300 °C are comparable to those of the Si/Sr ratio of 1.0 sample sintered at 1400 °C. However, in terms of afterglow properties, the former exhibits an enhancement by a factor of 3.5 compared to the latter. This finding suggests that strategically increasing the Si/Sr ratio can reduce the sintering temperature by 100 °C while maintaining or even enhancing the luminescence and afterglow properties of the samples. Additionally, the electronic structures of the Sr2MgSi2O7 host, the doped luminescence center Eu, the oxygen vacancies and the co-doped activator Dy have been methodically investigated through first-principles calculations. By integrating the findings on the distribution of the dopants and defects levels, we predict and propose the photoluminescence and afterglow mechanisms of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+. These studies suggest an efficient, cheap and energy-saving strategy for the preparation of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ long afterglow phosphor, and reveal the roles of oxygen vacancies and co-doped Dy in the afterglow luminescence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Long afterglow phosphors are a special kind of environment-friendly light source materials, ones not only have excellent photoluminescence performance, but also can store luminous energy from UV light, lamplight or sunlight and then release the energy slowly. The development of afterglow phosphors has been experienced from sulfides to aluminates to silicates. Long lasting phosphorescent silicates have been widely investigated for their excellent water resistance and good chemical stability1,2, among them Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ is presumably the best known persistent luminescent silicate, and its brightness and lifetime of the afterglow overshadows that of most silicates3,4,5.

Different methods were investigated to obtain Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ phosphor, such as solid state reactions6, sol-gel technique7 and microwave8. Photoluminescence and afterglow properties are also depended on the synthetic methods. The high temperature solid state reaction process, which is a conventional preparation technique, is commonly used in industrial production because of its simple technology, perfect crystalline quality, less surface defects, high luminescence brightness and long persistent duration. But some problems still exist such as high calcination temperature, long maintaining time and impurity phases. Solid state reaction often requires high sintering temperature. This is because atoms in the solid need enough energy to diffuse and migrate. The atoms are constantly vibrating around their equilibrium positions in solids, and the amplitude of this vibration will increase as the temperature rises. The energy obtained from the external environment will induce the release of atoms, thereby facilitating their diffusion and migration within the solid. The higher the temperature, the greater the proportion of diffuse atoms, thus promoting solid state reactions. In our research, we have found that a sintering temperature of at least 1400 °C is required to synthesize Sr2MgSi2O7 with good performance without adding flux. In addition, the Sr3MgSi2O8 phase is commonly observed as an impurity phase in the Sr2MgSi2O7 sample9,10,11, which will adversely affect the investigation of the performance of Sr2MgSi2O7. According to coordination polyhedron regulation of anion, silicium-oxygen tetrahedron [SiO4]4− is basic structural unit of silicate crystals. Therefore, the formation of Sr3MgSi2O8 phase with isolated orthosilicate anions [SiO4]4− is more readily achieved than Sr2MgSi2O7 phase with isolated double tetrahedra [Si2O7]6−. Consequently, the conventional solid state reaction synthesis of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ phosphors faces two critical challenges that limit their industrial implementation: (1) the excessively high sintering temperatures required for phase formation result in substantial energy consumption, and (2) the formation of impurity phases can significantly deteriorate the luminescence and afterglow performance of the material.

Silica, as a crucial raw material for solid state reaction of silicate phosphors, significantly influences the crystalline structure, luminescence and afterglow properties of the resulting materials. Y. Li et al. systematically investigated the effects of non-stoichiometry on photoluminescence and afterglow properties of Sr2MgSinO3 + 2n: Eu2+, Dy3+ (1.8 ≤ n ≤ 2.2) by solid-state reaction12. Their findings demonstrate that the samples with SiO2 excess possess better crystallinity and larger, and both photoluminescence intensity and afterglow performance have also improved. H. Y. Jiao et al. synthesized phosphors of Ca1.86Al2Si1+yO7 + 2y: 0.14Eu3+ (0 ≤ y ≤ 0.3) with excess SiO2, and confirmed that the photoluminescence intensity of the obtained phosphors is fairly enhanced by excessive SiO213. C. Deng et al. reported that bridging oxygen can be formed relatively easily in the Ca2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ phosphors with the increase of silicon-calcium stoichiometric ratio. This increases the formation of the Ca2MgSi2O7 and CaMgSi2O6 phases while inhibiting the generation of impurity phase Ca3MgSi2O814. In summary, the addition of an appropriate amount of silica during the high-temperature solid-state reaction process for synthesizing silicate phosphors containing double tetrahedra ([Si2O7]6−) not only enhances the luminescence and afterglow properties of the phosphors but also effectively prevents the formation of impurity phases with isolated orthosilicate anions ([SiO4]4−), such as Ca3MgSi2O8. However, the effects of excessive silica on the synthesis process of silicate phosphors, as well as the underlying mechanisms responsible for the observed improvements in luminescence and afterglow properties, still require further investigation and discussion.

In the present work, Sr1.94MgSi2O7: Eu2 + 0.01, Dy3 + 0.05 phosphors with different Si/Sr ratios were successfully prepared by solid state reaction method at different sintering temperature. Through a systematic investigation of the effects of varying the Si/Sr ratio at different sintering temperatures on the phases, crystallinity, grain size, solid state diffusion, reaction process, photoluminescence and afterglow properties of the Sr1.94MgSi2O7: Eu2 + 0.01, Dy3 + 0.05 phosphors, it was confirmed that increasing the Si/Sr ratio in the Sr2MgSi2O7 host effectively enhances the rate of solid state reaction, which has the same effect as increasing the sintering temperature. Therefore, the Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ phosphors with excellent photoluminescence and afterglow properties can be obtained by optimizing the Si/Sr ratio, and the sintering temperature can be reduced. In addition, despite numerous studies on the mechanism15,16,17, the afterglow mechanism of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ remains a subject of controversy. The electronic structures of Sr2MgSi2O7 host, dopants and oxygen vacancies (VO and VO2+) were obtained based on first-principles calculation. This theoretical investigation provides valuable support for elucidating the roles of dopant Dy and oxygen vacancies in long afterglow luminescence. The research results offer a valuable reference for the prediction of the afterglow luminescence mechanism of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+. These studies may have contribution to decrease the production cost, promote energy saving and improve industrial production efficiency.

Methods

Experimental methods

The samples Sr1.94MgSi2O7: Eu2 + 0.01, Dy3 + 0.05 with different SiO2 addition amount were synthesized by solid state reaction method at different temperature (1250 °C, 1300 °C, 1350 °C and 1400 °C), and the different amounts of SiO2 are measured by molar ratios of Si/Sr = 1, 1.1, 1.2, 1.3 and 1.4, respectively. solid powders SrCO3 (AR), MgO (AR), SiO2 (3 N), Eu2O3 (4 N) and Dy2O3 (3 N) were raw materials. The raw materials weighed according to stoichiometric ratio were mixed thoroughly in an agate mortar and pre-sintered at 800 °C for 2 h in air. The pre-sintering powders were ground again, pressed into tablets and sintered at different temperature (1250 °C, 1300 °C, 1350 °C and 1400 °C) for 4 h under a reducing atmosphere of carbon monoxide. However, the samples sintered at 1400 °C with Si/Sr ratios greater than 1 melted completely, thus only the sample Si/Sr = 1 (sintered at 1400 °C) was retained.

To determine the crystalline phases of all samples, a Rigaku Smartlab X-ray diffractometer (XRD) with Cu Kα radiation was utilized. The scan range (2θ) was from 10 to 80°. The morphologies and microstructures of samples were observed by Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). Room temperature emission and excitation spectra were measured on a HORIBA FluoroMax®-4 spectrofluorometer. Afterglow decay curves were recorded on the same spectrofluorometer, and all samples were irradiated by a 365 nm ultraviolet lamp for 30 min before the afterglow performance measurements.

Computational details and modeling

In order to thoroughly investigate the afterglow mechanism of long afterglow phosphors Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+, the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)18,19 was employed for the first-principles calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) to study the electronic properties of Sr2MgSi2O7 and the dopants and defects in it. The exchange-correlation functional is described by the generalized gradient approximation (GGA)20 with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE). The valence electron configurations in the calculation are Sr(4s24p65s2), Mg(2p63s2), Si(3s23p2), O(2s22p4), Eu(4f75d06s2), Dy(4f105d06s2), and the projector augmented wave (PAW) is used to describe the interaction between valence electrons and their respective nuclei. The modified Becke Johnson (mBJ) exchange-correlation potential is employed to modify the issue of underestimation in band gap21, thereby enhancing the congruity between calculated results and experimental data.

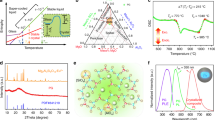

The crystal structure of Sr2MgSi2O7 is depicted in Fig. 1a. When constructing the doping and defect calculation models, the unit cell of Sr2MgSi2O7 was initially expanded into a 1 × 1 × 2 supercell. The oxygen vacancy model of Sr2MgSi2O7 was obtained by removing an O atom from the supercell, as shown in Fig. 1b. Since the ionic radii of Eu2+ (0.125 nm) and Dy3+ (0.1027 nm) are similar to the ionic radii of Sr2+ (0.126 nm) in Sr2MgSi2O7 crystal, the doped Eu2+ or Dy3+ ions enter the host to replace the lattice sites of Sr2+ ions. By substituting one Sr atom in the supercell with a Eu or Dy atom, the doping models of Sr1.875Eu0.125MgSi2O7 and Sr1.875Dy0.125MgSi2O7 were obtained, as illustrated in Fig. 1c and d, respectively.

Results and discussion

Phase identification and morphology

The XRD patterns of samples (Si/Sr = 1, 1.1, 1.2, 1.3 and 1.4) sintered at 1250 °C, 1300 °C and 1350 °C are shown in Fig. 2a, b and c, respectively. Figure 2d shows the XRD pattern of Si/Sr = 1 sample sintered at 1400 °C. The major diffraction peaks of all samples can be indexed to a tetragonal Sr2MgSi2O7 phase according to JCPDS Cards 75-1736. Sr2MgSi2O7 is the melilite-type crystal structure, which belongs to tetragonal crystallography with space group P-421m, and the corresponding lattice parameters are a = b = 7.9957 Å, c = 5.1521 Å, α = β = γ = 90°. In the XRD patterns of all Si/Sr = 1 samples sintered at 1250 °C to 1400 °C and Si/Sr = 1.1 sample sintered at 1250 °C, two diffraction peaks located approximately at 31.4° and 32.2° (indicated by “•”) are not attributed to Sr2MgSi2O7 phase. Based on the phase analysis, these two diffraction peaks matched well with the standard card of Sr3MgSi2O8 (JCPDS Cards 10–0075), which is consistent with the reports in literatures22,23,24. Thus, the impurity phase Sr3MgSi2O8 exists in these samples. With the continuous increase of Si/Sr ratio, Sr2MgSi2O7 phase (JCPDS Cards 75-1736) containing a small amount of excessive SiO2 (JCPDS Cards 85–0459, indicated by “♦”) is obtained, as shown in Fig. 2a, b and c.

(a–d) XRD patterns of Sr1.94MgSi2O7: Eu2 + 0.01, Dy3 + 0.05 phosphors with different silicium-strontium ratios (Si/Sr = 1, 1.1, 1.2, 1.3 and 1.4), and the sintering temperatures are (a) 1250 °C, (b) 1300 °C, (c) 1350 °C and (d) 1400 °C, respectively. (e–f), (b–d) Rietveld refinement of the Sr1.94MgSi2O7: Eu2 + 0.01, Dy3 + 0.05 (Si/Sr = 1) phosphors sintered at 1350 °C and 1400 °C, respectively.

As depicted in the XRD patterns of samples with Si/Sr = 1 (Fig. 2), it can be observed that impurity phase Sr3MgSi2O8 does not disappear as the sintering temperature rises. In the crystal structure of Sr3MgSi2O8, the ratio of silicon atoms to oxygen atoms is 1:4, so silicon-oxygen tetrahedron occurs as isolated [SiO4]4− center (Fig. 3 a). Figure 3b shows the crystal structure of Sr2MgSi2O7. Two tetrahedra are joined together by a bridging oxygen, and a double tetrahedra structure [Si2O7]6− is formed in the Sr2MgSi2O7 crystal structure. To eliminate the impurity phase Sr3MgSi2O8, it is imperative to facilitate the formation of bridge oxygen. In a reducing atmosphere, the Si/O ratio is enhanced as the silicon contents increase, which is beneficial to the formation of bridging oxygen in the Sr2MgSi2O7. Consequently, the impurity phase Sr3MgSi2O8 is eliminated with the increase of Si/Sr ratio.

The lattice parameters of all samples and Sr2MgSi2O7 calculation model by structure optimization are listed in Table 1. The lattice parameters basically expand first and then reduce with the increase of sintering temperature or Si/Sr ratio. The expansion of the lattice parameters caused by sintering temperature or Si/Sr ratio may be related to the high temperature lattice expansion and the introduction of excess Si atoms in the interstitial positions, respectively. However, as the sintering temperature or Si/Sr ratio continues to increase, the smaller lattice parameters may be caused by the increase of vacancies in the samples which will affect the afterglow performances. The lattice parameters of Sr2MgSi2O7 calculation model after structure optimization closely resemble those of the experimental samples, indicating that the geometrically optimized crystal structure is highly consistent with the experimental samples.

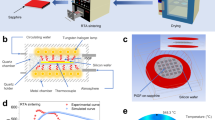

The SEM images of Si/Sr = 1, 1.1, 1.3 and 1.4 samples sintered at 1350 °C are shown in Fig. 4a, b, c and d, respectively, and the diagrammatic sketch of sintering process are shown in Fig. 4e–h. The particles in the unsintered tablets are only in point contact or not in contact at all, as depicted in Fig. 4e. At the initial sintering stage (Fig. 4f), the gas is expelled from the tablets, particles begin to rearrange and gather, and the particles of diffusion phases SrO and MgO are likely to surround SiO2. There is still point contact between the particles, but the number of contact points increases. Mass transfer is happened at the contact point with the increasing sintering temperature or holding time. The contact surface is gradually expanding and the grain boundary is formed. As the mass transfer continues, the area of grain boundary increases, porosity decreases, volume shrinks, and the new crystal phase is formed gradually (Fig. 4g). After that, the grains grow unceasingly, and the pores are expelled gradually with the movement of the grain boundary. Ultimately, the dense polycrystals are synthesized as shown in Fig. 4h.

The SEM image of Si/Sr = 1 sample sintered at 1350 °C shows a comparatively looser structure. There are many independent or connected pores in the Si/Sr = 1 sample. The loose porous crystal structure in Fig. 4a is similar to Fig. 4g, which illustrates the sample with many lattice defects is still in the stage of grain growth. This indicates that at Si/Sr = 1, a sintering temperature of 1350 °C only leads to the formation of Sr2MgSi2O7 crystal phase, while the reaction conditions fail to expel pores and achieve dense crystal. As shown in Fig. 4b, the SEM image of Si/Sr = 1.1 sample sintered at 1350 °C is similar to Fig. 4h. The sample has tetragonal crystal grains with uniform distribution, regular morphology and high denseness. When sintering temperature, holding time and atmosphere remain unchanged, the product can be changed from a loose porous crystal structure (Fig. 4a, representing the stage of grain growth) to the ideal dense polycrystals (Fig. 4b) by solely increasing the Si/Sr ratio. It is shown that the increase of Si/Sr ratio can effectively promote the diffusion mass transfer during solid state reaction and improve the rate of solid state reaction, which achieves the similar effect as raising the sintering temperature or prolonging the holding time.

In addition, the abnormal growth of grains with larger size caused by secondary recrystallization can be observed in the SEM image of Si/Sr = 1.3 sample (Fig. 4c), which is typically attributed to the rapid movement of grain boundaries resulting from excessive diffusion coefficient in solid state reaction. As depicted in Fig. 4d, when the Si/Sr ratio rises to 1.4, along with the abnormal grain growth phenomenon, an abundance of pores is also observed. The formation of this porous structure is caused by the over-rapid diffusion rate. Since the rate movement of grain boundary is obviously higher than that of pores during the secondary recrystallization, the grain boundaries may over the pores and these pores are hard to be expelled by bulk diffusion. The secondary recrystallization of samples Si/Sr = 1.3 and Si/Sr = 1.4 sintered at 1350 °C also reveals that the grain growth rate escalates with the Si/Sr ratio. This finding further substantiates the conclusion that an increased Si/Sr ratio can effectively enhance the rate of solid state reaction, and its effect is similar to the increase of sintering temperature. The melting of all samples with excess Si content at 1400 °C also illustrates that increasing both the Si/Sr ratio and the sintering temperature results in similar enhancements of solid state reaction rate.

The solid state reaction rate is accelerated with the increase of the Si/Sr ratio, which can also be explained by solid state diffusion and reaction process. In the multicomponent reaction system for synthesizing Sr2MgSi2O7, the solid state reaction rate depends on the slower diffusion particles. The highly charged ions such as Si4+ are less free to migrate than divalent ions25. Thus, the cations Sr2+ and Mg2+ are the migrating ions, and the reaction rate depends very much on the diffusion of Si4+ ions. The concentration of Si4+ increases with the augmentation of silicon content in raw materials, which is beneficial to improving the contact opportunity of reactants and promoting the diffusion of Si4+ ions, thereby leading to an increased rate of solid state reaction. Based on principles of solid state reaction and crystallography of silicates, the reaction process is depicted in equations in Fig. 5. In the solid state reaction of Sr2MgSi2O7, the synthesis of both the initial products and the crucial intermediate product necessitate SiO2 participation. Therefore, enhancing the quantity of SiO2 addition in the raw material can effectively enhance the areas of reaction interface, thereby significantly augmenting the rate of solid state reaction.

Photoluminescence properties

Figure 6a shows the photoluminescence excitation spectra of all samples, and all excitation spectra are monitored by 467 nm. A broad excitation band is exhibited in each excitation spectrum and the excitation peak is located at about 397 nm. However, two other excitation bands centered at about 358 nm and 370 nm are shown in excitation spectra of all Si/Sr = 1 samples and Si/Sr = 1.1 sample sintered at 1250 °C, which corresponds to the excitation spectrum of Sr3MgSi2O8: Eu2+ reported in literature26. According to the results of phase analysis, the diffraction peaks corresponding to the Sr3MgSi2O8 phase of these samples were also identified in the XRD patterns. Consequently, the abnormal excitation peaks observed in these samples are attributed to the excitation of impurity phase Sr3MgSi2O8: Eu2+.

Emission spectra (λex = 397 nm) for all samples are shown in Fig. 6b. There is only one 467 nm emission band in the emission spectrum of each sample. All emission bands are attributed to the 4f7-4f65d1 typical transition of Eu2+27. No special emission peaks of Dy3+ and Eu3+ are observed in the emission spectra28,29. The emission peak of Sr3MgSi2O8: Eu2+ is located near 457 nm26, which is close to the position of the emission peak of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+. Therefore, no obvious emission peak of impurity phase Sr3MgSi2O8: Eu2+ is found in the emission spectra of all Si/Sr = 1 samples and Si/Sr = 1.1 sample sintered at 1250 °C. Additionally, since the impurity phase SiO2 does not exhibit a remarkable emission, it does not influence the position of the emission peak of the major phase Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+. However, it may have a slight impact on the photoluminescent intensity of the samples30.

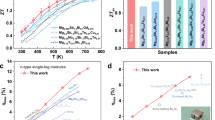

Figure 7 exhibits the dependence of the photoluminescence intensity on sintering temperature. As shown in Figs. 6b and 7, at the same sintering temperature, the photoluminescence intensity of all samples changes regularly with the Si/Sr ratio. With the increase of Si/Sr ratio, the photoluminescence intensity of samples gradually increases at 1250 °C, when sintering temperature is raised to 1300–1350 °C, the photoluminescence intensity first increases and then decreases. When the sintering temperatures are set at 1250 °C, 1300 °C and 1350 °C, the samples with the optimum photoluminescence performance are Si/Sr = 1.4, Si/Sr = 1.3 and Si/Sr = 1.1, respectively. The property of Si/Sr = 1.4 sample sintered at 1250 °C is almost twice that of Si/Sr = 1 sample sintered at 1300 °C, and is similar to the performance of Si/Sr = 1 sample sintered at 1350 °C. The photoluminescence intensity of Si/Sr = 1.3 sample sintered at 1300 °C is almost the same as Si/Sr = 1 sample sintered at 1400 °C, and the photoluminescence performance of Si/Sr = 1.1 sample sintered at 1350 °C is the best of all. These descriptions of photoluminescence properties provide three results: (1) The appropriate increase of Si/Sr ratio can improve the photoluminescence property at the same sintering temperature. (2) Properly enhancing the Si/Sr ratio can reduce the sintering temperature by 100 °C and maintain good photoluminescence performance. (3) To obtain samples with excellent photoluminescence performances, the higher the sintering temperature is, the smaller the required Si/Sr ratio is.

The relationship between photoluminescence intensity and sintering temperature of samples with different Si/Sr ratios is shown on the right side of Fig. 7. The photoluminescence intensities of Si/Sr = 1, 1.1 and 1.2 samples increase steadily as sintering temperature increases, but the variation curve of Si/Sr = 1.2 tends to be gentle when the temperature rises from 1300 °C to 1350 °C. Nevertheless, the intensity of Si/Sr = 1.3 sample reaches the peak at 1300 °C and then starts to fall, and the intensity of Si/Sr = 1.4 sample falls off precipitously with the increase of sintering temperature. The regularity of the above trend graph further proves that the photoluminescence performance deteriorates when the temperature and the Si/Sr ratio increase simultaneously.

The photoluminescence properties of samples are improved by increasing sintering temperature or adding Si/Sr ratio within an appropriate range. However, a higher Si/Sr ratio leads to a decrease in the required sintering temperature. On the one hand, sintering temperature is an important factor for the solid state reaction. Diffusion is often the only way of mass transfer in solids. Generally, the higher the sintering temperature is, the faster the rate of atom diffusion is. The enhanced diffusion rate can facilitate activator and auxiliary activator entering into the appropriate lattice sites and be beneficial to expelling the pores in the materials, so the effective density of doped ions and sintered density are improved by raising sintering temperature. On the other hand, raising the proportion of silica in reactants facilitates the sufficient dispersion of SrO and MgO particles around SiO2 at the rearrangement stage, which enlarges the areas of reaction interface and diffusion boundary. Therefore, the increase of Si/Sr ratio can also enhance the rate of solid state reaction and facilitate the activator entering the crystal lattice. In conclusion, whether sintering temperature or Si/Sr ratio increases, the rate of solid state reaction can be improved. Obviously, increasing the Si/Sr ratio yields a similar effect to raising the sintering temperature, thereby enhancing the Si/Sr ratio can reduce the sintering temperature.

In addition, the photoluminescence performances of the samples are also affected by the crystallization properties. As the result of SEM analysis, Si/Sr = 1.1 sample sintered at 1350 °C has very regular hexahedron crystal morphology with well crystallization, so it has the best photoluminescence performance. The large grains caused by abnormal grain growth appear in SEM image of Si/Sr = 1.3 sample sintered at 1350 °C and result in poor photoluminescence performance. The poor crystallinity and looser structure also lead to the poor photoluminescence property of Si/Sr = 1.4 sample sintered at 1350 °C. Thus, the optimization of sintering temperature and Si/Sr ratio is crucial for controlling normal grain growth in order to achieve ideal polycrystalline materials, thereby enhancing the photoluminescence performance.

Afterglow characteristics

The decay curves in Fig. 8a–d exhibit variations corresponding to the Si/Sr ratio, and the dependence of the initial brightness of the afterglow on sintering temperature is illustrated in Fig. 8e. As shown in Fig. 8a–d, afterglow properties of samples exhibit enhancement with the increasing of Si/Sr ratio. The afterglow properties of Si/Sr = 1.4 samples sintered at 1250 °C, 1300 °C and 1350 °C are enhanced about 42, 27 and 13 times, respectively when compared to the Si/Sr = 1 samples sintered at the same temperature. Although the photoluminescence properties of Si/Sr = 1.3 sample sintered at 1300 °C and Si/Sr = 1 sample sintered at 1400 °C are similar, the former demonstrates the afterglow performance approximately 3.5 times greater than that of the latter. Therefore, the good photoluminescence and afterglow properties Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ phosphors can be obtained through adjustment of Si/Sr ratio, and the sintering temperature can be reduced by at least 100 °C. This is attributed to the fact that a high concentration of traps can enhance the afterglow performance, while the incorporation of excess SiO2 is beneficial for improving trap density12. In previous literatures, both Dy3+ ions and oxygen vacancies are important electron traps31,32,33,34,35,36. The doped Dy3+ ions not only introduce deeper electron traps but also act as electron donors. The higher Si/Sr ratio is conducive to raising the rate of atom diffusion and doping Dy3+ ions into the lattice, so the effective density of Dy3+ ions is improved by increasing Si/Sr ratio. Furthermore, when the samples were synthesized under a high temperature reducing atmosphere, the addition of excess SiO2 resulted in an imbalanced Si/O ratio (oxygen deficiency), which favored the formation of oxygen vacancies. In consequence, the afterglow performance is ameliorated as the effective trap density increases.

As shown in Fig. 8a–e, afterglow properties of Si/Sr = 1 and Si/Sr = 1.1 samples are also improved as the sintering temperature increases. When the Si/Sr ratio is relatively low, the high sintering temperature can improve the crystallization capacity, facilitate Eu2+ and Dy3+ ions entering the crystal lattice and promote the formation of oxygen vacancies, thereby enhancing photoluminescence and afterglow properties. However, as the Si/Sr ratio increases (≥ 1.2), the differences in afterglow properties among samples sintered at different temperatures become less pronounced. This can be attributed to the fact that the effective trap density tends to be constant with the increased rate of solid state reaction. The afterglow properties of all Si/Sr = 1.4 samples are almost identical, surpassing the performance of Si/Sr = 1 sample sintered at 1400 °C by nearly 4 times. If only the afterglow performance is taken into consideration, the Si/Sr = 1.4 sample sintered at 1250 °C emerges as the optimal choice. This indicates that by increasing the Si/Sr ratio within an appropriate range, the Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ phosphors with excellent afterglow performances can be synthesized at a lower sintering temperature. In addition, the afterglow properties of Si/Sr = 1.4 samples are hardly influenced by the crystallization as the sintering temperature rises, suggesting that the afterglow performance of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ sample is primarily determined by the trap levels.

Electronic structures

The computed energy band structure and total and partial density of states are shown in Fig. 9. As shown in Fig. 9a, The conduction band minimum (CBM) of host Sr2MgSi2O7 is located at the high symmetry point G, while the valence band maximum (VBM) is situated at the point Z, which belongs to indirect band gap. The calculation results reveal that Sr2MgSi2O7 is an insulator with band gap width of 6.88 eV, which closely matches the experimental value of 7.1 eV obtained by Tuomas Aitasalo et al. using UV-VUV synchrotron radiation37. Figure 9b illustrates the calculated energy band structure and density of states of Eu-doped Sr2MgSi2O7. The Fermi level is positioned above the 4f levels of Eu within the band gap, indicating that the 4f levels within the band gap are occupied by electrons. The empty 5d levels of Eu are situated within the energy range of 0.61–4.42 eV above the bottom of the conduction band. Consequently, under the excitation of ultraviolet light, the electron occupied the 4f levels of Eu absorb energy and transition to the unoccupied 5d levels. Subsequently, when the electrons in the 5d levels move back to the 4f levels, the characteristic emission of Eu occurs. Due to the fact that the 5d levels of Eu are located in the conduction band, the electrons excited to the 5d levels have the potential to enter the conduction band as free electrons. which may be captured by the defect energy levels in the crystal, and thus forming the phenomenon of afterglow.

We calculated the electronic structure of the oxygen vacancy (VO) and the oxygen vacancy with two charges (VO2+) in Sr2MgSi2O7, respectively. The corresponding energy band structures and density of states diagrams are presented in Fig. 9c and d, respectively. The defect energy levels of VO and VO2+ are located at 1.19–1.34 eV and 0.85–1.22 eV below the conduction band minimum, respectively, which are close to the bottom of the conductive band and easy to capture free electrons in the conductive band. Moreover, the electrons can easily escape from the trap levels by thermal activation and re-enter the conductive band. If they return to the 5d levels of Eu and transition back to the 4f levels, the afterglow is generated. Therefore, both oxygen vacancy (VO) and charged oxygen vacancy (VO2+) are effective electron capture traps, playing a crucial role in the afterglow emission of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu, respectively.

In order to clarify the contribution of Dy in afterglow luminescence, the electronic structure of Sr2MgSi2O7 doped with Dy was calculated. The obtained energy band structures and density of states are illustrated in Fig. 9e. The 4f levels of Dy within the forbidden band is distributed in the energy range of 2.72–4.51 eV below the conduction band, which is deeper than the trap levels generated by the oxygen vacancy, so the captured electrons are not easy to escape from the trap and return directly to the conduction band. The trapped electrons can undergo movements within the 4f levels of Dy until they reach the top of 4f trap level, or move to a nearby defect levels created by oxygen vacancy, and then move back to the conduction band. When they revert to the 5d levels of Eu, the afterglow may occur. Therefore, the trap levels generated by Dy play a key role in reducing the decay rate of afterglow and prolonging the luminescence time of afterglow.

Mechanism of afterglow luminescence

The schematic diagram illustrating the afterglow luminescence mechanism of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu, Dy is shown in Fig. 10. The emission spectrum of Eu in Sr2MgSi2O7 is attributed to the characteristic emission of Eu2+ resulting from the transition between the 4f65d1 excited state and the 4f7 ground state. The calculation results reveal that the 5d energy level of Eu is situated within the conduction band. When 4f electrons of Eu are excited and transition to the empty 5d levels, it is easy for them to enter the conduction band and become free electrons. These free electrons in the conduction band may be captured by the trap levels such as oxygen vacancies or the 4f levels of Dy if they move near them. The trap levels generated by oxygen vacancies are close to the conduction band bottom and belong to shallow trap levels. The electrons captured by them can easily overcome the potential energy of the trap through thermal activation and return to the conduction band. Since the 5d levels of Eu is distributed above 0.61 eV from the conduction band bottom and has a small energy difference with the conduction band minimum. Free electrons, upon returning to the conduction band and approaching Eu, can re-enter the 5d levels of Eu, and then transition back to the 4f levels, thereby inducing the afterglow luminescence. The trap levels of Dy are relatively deep, so the captured electrons are not easy to return to the conduction band directly through thermally excitation. The electrons can be continuously transferred to the nearby 4f levels of Dy through thermal vibration until they reach the top of trap level, or move to the nearby trap levels of oxygen vacancy, and then they may further return to the conduction band, resulting in afterglow emission. The electrons captured by Dy 4f levels requires a relatively long process to return to the conduction band. Hence, the doping of Dy not only enhances the number of electron traps and captured electrons, but also effectively reduces the afterglow decay rate, prolongs the afterglow luminescence time and improve the afterglow performance.

Conclusions

In the process of solid state reaction to synthesize Sr2MgSi2O7, increasing Si/Sr ratio can enhance the reaction rate, which is beneficial to the elimination of impurity phase Sr3MgSi2O8 and promotes the formation of Sr2MgSi2O7 phase. Additionally, it facilitates the growth of crystalline grain and the substitution of activator into the crystal lattice, exhibiting a similar effect to that achieved by raising sintering temperature. The photoluminescence performance of Si/Sr = 1.1 sample sintered at 1350 °C is the best of all. The photoluminescence intensity of Si/Sr = 1.3 sample sintered at 1300 °C is almost the same as Si/Sr = 1 sample sintered at 1400 °C, which is the second highest following the Si/Sr = 1.1 sample sintered at 1350 °C. Even with a reduction of 100 °C in the sintering temperature, the excellent luminescence properties can still be maintained. Therefore, the sample with good photoluminescence performance resulting from well crystallization and effective density of activators can be obtained through controlling Si/Sr ratio and sintering temperature within an appropriate range. However, the photoluminescence property may deteriorate due to the secondary crystallization when the sample has a large Si/Sr ratio and the sintering temperature is too high. The afterglow property of Sr1.94MgSi2O7: Eu2 + 0.01, Dy3 + 0.05 mainly depends on the trap levels rather than the crystallization. The increase of the Si/Sr ratio is beneficial for improving trap density, resulting in significant improvements in the afterglow brightness, decay rate and luminescence time of Sr1.94MgSi2O7: Eu2 + 0.01, Dy3 + 0.05. The calculation results reveal that the oxygen vacancies (VO and VO2+) and Dy 4f levels introduce trap levels of different depths in the host of Sr2MgSi2O7, which can effectively capture the electrons of Eu entering the conduction band. The addition of excess SiO2 not only promotes the incorporation of Dy3+ into the lattice but also facilitates the formation of oxygen vacancies, thereby enhancing the effective trap density and improving the afterglow properties of the samples. In short, the research results of this work provide technical and theoretical guidance for optimizing the preparation process of Sr1.94MgSi2O7: Eu2 + 0.01, Dy3 + 0.05, improving luminescence and afterglow performance, thus effectively promoting energy conservation and reducing production costs.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from thecorresponding author on reasonablerequest.

References

Hai, O. et al. Exploration of long afterglow luminescence materials work as round-the-clock photocatalysts. J. Alloys Compd. 866, 158752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom (2021).

Zhang, J., Jin, Y., Wu, H., Chen, L. & Hu, Y. Giant enhancement of a long afterglow and optically stimulated luminescence phosphor BaCaSiO4: Eu2+ via Pr3+ codoping for optical data storage. J. Lumin. 263, 119971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2023.119971 (2023).

Zou, L. et al. Enhanced long afterglow luminescence of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ by NH4Cl. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 146, 110151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2022.110151 (2022).

Van den Eeckhout, K., Smet, P. F. & Poelman, D. Persistent luminescence in Eu2+-doped compounds: a review. Materials 3, 2536–2566. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma3042536 (2010).

Yang, E. et al. Improved trap capability of shallow traps of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ through depositing Au nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 858, 157705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.157705 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. A new method for preparing cubic-shaped Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ phosphors and the effect of sintering temperature. Ceram. Int. 48, 5397–5403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.11.083 (2022).

Homayoni, H. et al. X-ray excited luminescence and persistent luminescence of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ and their associations with synthesis conditions. J. Lumin. 198, 132–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2018.02.042 (2018).

Pan, L. et al. Optimization method for blue Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ phosphors produced by microwave synthesis route. J. Alloys Compd. 737, 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.11.343 (2018).

Zhang, C., Gong, X. Y. & Deng, C. Y. The phase transition of color-tunable long afterglow phosphors Sr1.94–xBaxMgSi2O7: Eu2 + 0.01, Dy3 + 0.05. J. Alloys Compd. 657, 436–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.10.093 (2016).

Zhou, Z. et al. New viewpoint about the effects of boric acid on luminous intensity of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu, dy. Mater. Res. Express 6, 086205. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/ab1dd0 (2019).

Wu, H., Hu, Y., Wang, Y., Kang, F. & Mou, Z. Investigation on Eu3+ doped Sr2MgSi2O7 red-emitting phosphors for white-light-emitting diodes. Opt. Laser Technol. 43, 1104–1110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2011.02.006 (2011).

Li, Y., Wang, Y., Xu, X. & Gong, Y. Effects of non-stoichiometry on crystallinity, photoluminescence and afterglow properties of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ phosphors. J. Lumin. 129, 1230–1234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2009.06.014 (2009).

Jiao, H. Y., LiMao, C. R., Chen, Q., Wang, P. Y. & Cai, R. C. Enhancement of red emission intensity of Ca2Al2SiO7: Eu3+ phosphor by MoO3 doping or excess SiO2 addition for application to white leds. Mater. Sci. Eng. 292, 012058. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/292/1/012058 (2018). IOP Conf. Ser.

Zhang, C., Gong, X. Y., Cui, R. R. & Deng, C. Y. Improvable luminescent properties by adjusting silicium-calcium stoichiometric ratio in long afterglow phosphors Ca1.94MgSi2O7: Eu2 + 0.01, Dy3 + 0.05. J. Alloys Compd. 658, 898–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.10.209 (2016).

Yang, L. et al. Recent progress in inorganic afterglow materials: Mechanisms, persistent luminescent properties, modulating methods, and bioimaging applications. Adv. Opt. Mater.. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.202202382 (2023).

Zeng, P., Wei, X., Yin, M. & Chen, Y. Investigation of the long afterglow mechanism in SrAl2O4: Eu2+/Dy3+ by optically stimulated luminescence and thermoluminescence. J. Lumin. 199, 400–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2018.03.088 (2018).

Yang, X., Waterhouse, G. I. N. & Lu, S. Yu. Recent advances in the design of afterglow materials: Mechanisms, structural regulation strategies and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 8005–8058. https://doi.org/10.1039/D2CS00993E (2023).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B. 47, 558. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.47.558 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for Ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.54.11169 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77 3865–3868. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865 (1996).

Tran, F. & Blaha, P. Accurate band gaps of semiconductors and insulators with a semilocal exchange-correlation potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 226401. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.226401 (2009).

Pan, W. & Ning, G. Synthesis and luminescence properties of Sr3MgSi2O8: Eu2+, Dy3+ by a novel silica-nanocoating method. Sens. Actuat A Phys. 139, 318–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2006.12.021 (2007).

Yu, H. et al. Green light emission by Ce3+ and Tb3+ co-doped Sr3MgSi2O8 phosphors for potential application in ultraviolet whitelight-emitting diodes. Opt. Laser Technol. 44, 2306–2311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2012.02.005 (2012).

Chen, Y., Zhou, B., Sun, Q., Wang, Y. & Yan, B. Synthesis and luminescence properties of Sr3MgSi2O8: Ce3+, Tb3+ for application in near ultraviolet excitable white light-emitting-diodes. Superlattice Microstruct. 100, 158–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spmi.2016.09.017 (2016).

Brindley, G. W. & Hayami, R. Kinetics and mechanism of formation of forsterite (Mg2SiO4) by solid state reaction of MgO and SiO2. Philos. Mag. 12, 505–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786436508218896 (1965).

Gong, Y. et al. The persistent energy transfer of Eu2+ and Mn2+ and the thermoluminescence properties of long-lasting phosphor Sr3MgSi2O8: Eu2+, Mn2+, Dy3+. Opt. Mater. 33, 1781–1785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optmat.2011.06.015 (2011).

Hai, O. et al. Effect of cooling rate on the microstructure and luminescence properties of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+ materials. Luminescence 32, 1442–1447. https://doi.org/10.1002/bio.3343 (2017).

Reddy, L. A review of the efficiency of white light (or Other) emissions in singly and Co-Doped Dy3+ ions in different host (Phosphate, silicate, aluminate. Mater. J. Fluoresc. 33, 2181–2192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10895-023-03250-y (2023).

Li, M. et al. Tunable luminescence in Sr2MgSi2O7: Tb3+, Eu3+ phosphors based on energy transfer. Materials 10, 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10030227 (2017).

Kunimoto, T., Honma, T., Ohmi, K., Okubo, S. & Ohta, H. Detailed impurity phase investigation by X-ray absorption fine structure and Electron spin resonance analyses in synthesis of CaMgSi2O6: Eu phosphor. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 042402. https://doi.org/10.7567/JJAP.52.042402 (2013).

Li, Z. et al. Mechanism of long afterglow in SrAl2O4: Eu phosphors. Ceram. Int.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.08.193 (2021).

Hai, O. et al. Insights into the element gradient in the grain and luminescence mechanism of the long afterglow material Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+. J. Alloys Compd. 779, 892–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.11.163 (2019).

Qu, B. Y., Zhang, B., Wang, L., Zhou, R. L. & Zeng, X. C. Mechanistic study of the persistent luminescence of CaAl2O4: Eu, Nd. Chem. Mater. 27, 2195–2202. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b00288 (2015).

Yang, X., Tang, B. & Cao, X. The roles of Dopant concentration and defect States in the optical properties of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, Dy3+. J. Alloys Compd. 949, 169841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.169841 (2023).

Sahu, I. P., Bisen, D. P., Brahme, N. & Ganjir, M. Enhancement of the photoluminescence and long afterglow properties of Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+ phosphor by Dy3+ co-doping. Luminescence 30, 1318–1325. https://doi.org/10.1002/bio.2900 (2015).

Chang, C. et al. Photoluminescence and afterglow behavior of Eu2+, Dy3+ and Eu3+, Dy3+ in Sr3Al2O6 matrix. J. Lumin. 130, 347–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jlumin.2009.09.016 (2010).

Aitasalo, T. et al. Synchrotron radiation investigations of the Sr2MgSi2O7: Eu2+, R3+ persistent luminescence materials. J. Rare Earth 27, 529–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1002-0721(08)60283-5 (2009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Z.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. L.W.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. R.C.: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Q.L.: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. C.D.: Software, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. J.L.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, C., Wei, L., Liu, Q. et al. Improving preparation and luminescence properties of Eu and dy doped Sr2MgSi2O7 phosphors by adding excess silica. Sci Rep 15, 18367 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02948-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02948-2