Abstract

Our study aims to assess the moderating effect of self-esteem in the association between generalized anxiety disorder and disordered eating symptoms among a sample of Lebanese adults. The study engaged a cohort of 629 participants, who were recruited in May 2023, utilizing a snowball sampling technique. Data were collected via a questionnaire that included socio-demographic variables and the following scales: the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-5), the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-7), and the Single Item Self-Esteem Scale (SISE). Higher GAD-5 scores (Beta = 0.01; p = .004) were significantly associated with higher EAT-7 scores. The interaction generalized anxiety disorder by self-esteem was also significantly associated with EAT-7 scores (Beta = − 0.003; p = .019), indicating that self-esteem moderates the relationship between GAD and disordered eating symptoms. At low (Beta = 0.006; p = .001) and moderate (Beta = 0.003; p = .007) levels of self-esteem, higher GAD-5 scores were significantly associated with higher EAT-7 scores (more severe disordered eating symptoms). In contrast, at high levels of self-esteem, the association was not significant (Beta = 0.001; p = .812), indicating that higher self-esteem may act as a protective factor, reducing the impact of GAD on disordered eating symptoms. While an association between anxiety and disordered eating symptomatology has been reported, this study adds to the body of literature by indicating that the strength of this association may vary with an individual’s level of self-esteem, which underscores the importance of integrating self-esteem-building strategies into therapeutic interventions aimed at reducing disordered eating in individuals facing anxiety. Future studies would allow for a more dynamic and nuanced understanding of the causal pathways between anxiety, self-esteem, and eating behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Eating Disorders (EDs) are defined as psychiatric conditions that encompass a range of problematic eating behaviors, such as binge eating, bulimia nervosa, and anorexia nervosa, leading to impairments in physical health and psychosocial functioning1. A systematic review of data spanning from 2000 to 2018 reported that the prevalence of EDs rose from 3.5% during the 2000–2006 period to 7.8% between 2013 and 20182. A more recent review of studies conducted in the Arab world indicated that the estimates of individuals at high risk for EDs ranged from 2 to 54.8%3. Individuals with EDs have yearly healthcare costs that are 48% higher than those of the general population, along with increased risks for fertility problems and adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes4. Moreover, EDs are associated with a higher risk of premature mortality compared to other psychiatric disorders, mainly due to medical complications and suicide5,6,7,8.

However, EDs are often preceded by less severe and less frequent, yet risky, nonnormative eating behaviors. Notably, Disordered Eating (DE) refers to a spectrum of maladaptive, unhealthy eating (such as continuous concerns about controlling and losing weight, dieting, food restriction, and insufficient calorie intake) without meeting the diagnostic threshold for EDs9,10. DE are of particular concern due to their long-term negative impact on physical and mental health11 and their potential to escalate into clinically significant EDs such as anorexia nervosa, which has the highest mortality rates compared to other EDs12, underscoring the importance of exploring the underlying factors driving such DE. One of the most commonly used screening tools to assess DE, particularly atypical preoccupation with food and weight, in both clinical and non-clinical settings, is the Eating Attitudes Test in its original (EAT-40) or shortened (EAT-26, EAT-7) versions13.

A growing body of research suggests that both sociodemographic characteristics and mental health factors play critical roles in shaping DE behaviors. Demographic factors such as sex, marital status, education level, age, and socioeconomic background were shown to be associated with eating attitudes14. For instance, research indicates that gender is a key factor in determining eating habits, with societal pressures regarding body image frequently having a greater impact on women than on males15. In addition, as individuals age, their dietary habits undergo changes, leading to reduced food consumption and alterations in food preferences16. Similar to how living alone versus with a partner or family can affect eating habits, marital status also plays a role, with single or widowed individuals —especially men— being more likely to have restricted dietary variety, particularly with vegetables, while those cohabiting often demonstrating healthier eating patterns17. Furthermore, socioeconomic status (SES) affects dietary habits, with lower education and income resulting in unbalanced meals, while higher SES promoting healthier eating through better nutritional knowledge and financial affordability of higher-quality diets18.

Beyond sociodemographic variables, mental health has received substantial attention in the context of DE behaviors. Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) is characterized by persistent and excessive worry that could be multifaceted, including financial, family, health, and future concerns19,20. Positive associations between anxiety levels in everyday life and restrained eating have been reported. Restrained eating behaviors can operate as safety cognitions and behaviors offering a sense of control, such as controlling weight and body shape21. In terms of chronology appearance, anxiety disorders tend to precede the development of EDs22. In one prospective study, GAD was inversely correlated with overweight23. In another study, thin participants were more likely to meet the criteria of GAD24. Therefore, investigating the complex relationship between anxiety and eating patterns is essential for understanding etiological models and for developing preventive strategies, early intervention programs, and effective therapies.

While extensive research has been conducted to investigate the relationship between anxiety and eating behaviors, it is becoming increasingly obvious that numerous elements might influence the strength of this association; among these, self-esteem has recently come under scrutiny25. Self-esteem has a tremendous impact on how people perceive and respond to their bodies, behaviors, and self-concept26. The results of empirical studies on self-esteem’s moderating effect on the link between anxiety and eating behaviors are intriguing but not always consistent indicating the need for further investigation27. According to some studies, those who have high self-esteem may be more resilient and have a better satisfaction with life28,29, which would function as a buffer against the negative effects of anxiety on eating patterns. On the other hand, those with low self-esteem can be more vulnerable to the negative effects of worry, which could encourage attitudes and behaviors related to DE30.

The present study

Since 2019, the Lebanese population has faced an unrelenting economic collapse and political instability, with the Lebanese pound losing nearly 90% of its value, leading to acute shortages in essential goods25. The Economic crisis was followed by the COVID-19 pandemic and the Beirut port explosion on August 4, 2020. These adverse events were responsible for a mental health decline and heightened levels of anxiety among citizens31. The economic downturn causes food insecurity and price fluctuations25 and catalyzes changes in dietary choices and behaviors32. A 2017 published Lebanese study reported that bulimia nervosa was the most prevalent ED (46.1%), followed by anorexia nervosa (39.4%) and binge eating (14.4%)33. Previous studies conducted on Lebanese young adults showed a desire to become thin, avoidance of particular foods, an awareness of caloric content, and risky weight control measures3,34,35. These factors, coupled with the decline in mental health following multiple stressful events, could make the Lebanese population more vulnerable to an increased prevalence of EDs.

The main objective of the present study is to assess the moderating effect of self-esteem in the association between generalized anxiety disorder and DE symptoms among a sample of Lebanese adults. We hypothesize that individuals with higher levels of self-esteem will exhibit a weaker association between GAD and DE symptoms, suggesting that self-esteem may act as a protective factor against the influence of anxiety on eating behaviors. Ultimately, we aim to provide insights that could inform the development of targeted interventions and prevention strategies to mitigate the negative impact of GAD on eating behaviors.

Methods

Study design

Utilizing a snowball sampling technique, a survey was meticulously designed using Google forms and disseminated through various digital platforms, including messaging applications and social media networks (WhatsApp, Instagram, and Messenger). The study engaged a cohort of 629 participants, who were recruited in May 2023. The eligibility criteria for participation encompassed: (1) being a resident and citizen of Lebanon, (2) attaining the age of 18 years or older, (3) with no current diagnosed psychiatric illness or current or past diagnosis of an eating disorder, and (4) possessing internet access. Participants unwilling to complete the questionnaire were excluded. Upon granting digital informed consent, participants were prompted to undertake the instruments detailed below. The survey was conducted under the principles of anonymity, with participants engaging voluntarily and without any form of remuneration. On average, the completion of the survey spanned approximately 10 min29.

Minimal sample size calculation

Employing the formula proposed by Fritz and MacKinnon36 for sample size estimation, our study determined a minimal sample size of 411 participants. The formula utilized is \(\:n=\frac{L}{{f}^{2}}+k+1\), where f=0.14 represents a small effect size, L=7.85 corresponds to an α error of 5% and a power β of 80%, and k = 9 denotes the number of variables to be incorporated in the model.

Questionnaire

In our research, we held the principles of confidentiality in the highest regard. Our comprehensive study explored sociodemographic variables, including age, sex, educational background, marital status, and lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol consumption, and car ownership). The Household Crowding Index (HCI) was calculated to understand the living circumstances by dividing the total number of people in a household by the number of rooms, excluding the kitchen and bathrooms37. A household is considered uncrowded if the HCI was below 1, moderately crowded if between 1 and 2, and severely crowded if greater than 237. To measure the financial pressure felt by participants, we asked them to rate their financial situation on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 representing the lowest and 10 representing the highest level of pressure38. Moreover, participants were asked to self-report their height and weight, allowing us to calculate their Body Mass Index (BMI) using the formula: BMI = weight (kg) / height squared (m²) and group them according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification into four categories: ‘underweight’ (BMI < 18.5 kg/m²), ‘normal weight’ (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m²), ‘overweight’ (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m²), and ‘obesity’ (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m²)39. Additionally, they reported their physical activity through the Physical Activity Index (PAI): PAI = Intensity × Duration × Frequency40.

The survey also included the Arabic-validated version of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-5)41, which consists of 5 items evaluating anxiety symptoms experienced in the last two weeks (e.g., “I feel nervous, anxious, or about to burst”). Participants evaluated how well each statement described their recent experiences on a ten-point Likert scale (“0 = does not describe me and 10 = describes me exactly) (in this study, McDonald’s ω = 0.95 and Cronbach’s α = 0.95).

The Arabic-validated version of the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-7)13 was used to assess DE symptoms. This self-report measure is intended to screen eating disturbances in general, as a first step of two-step diagnostic procedure involving clinical interview42. Of note, this tool is not useful if one is screening for specific eating disorders42. Responses vary from 0 (never) to 3 (always) (e.g., “Avoid eating when I am hungry,”). Higher scores indicate more inappropriate eating attitudes (in this study, McDonald’s ω = 0.87 and Cronbach’s α = 0.87).

The Arabic version of the single item self-esteem scale (SISE) was used to measure self-esteem, through a single question on a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all true of me to 5 = very true of me)43.

Statistical analysis

The data analysis was conducted using SPSS software. The database contained no missing data. To assess the reliability of all scales, we calculated McDonald’s omega and Cronbach’s alpha values. Observing that the EAT-7 score distribution deviated from normality (skewness = 2.926, kurtosis = 9.895), we strategically applied a LOG transformation to the score. This adjustment yielded a distribution that conformed to normality, as confirmed by the calculated skewness (1.553) and kurtosis (1.325) values falling within the range of ± 244. For comparative analysis of two means, the Student t-test was employed, while Pearson’s correlation test was utilized to explore the relationship between two scores. To explore the intricacies of the relationship between GAD (independent variable) and eating attitudes (dependent variable), with self-esteem serving as the moderator, we engaged the Process Macro v.3.4 model 1 for SPSS45. Interaction terms were probed by examining the association of generalized anxiety disorder with disordered eating at the mean, 1 SD below the mean, and 1 SD above the mean of the moderator (self-esteem). Variables that exhibited a p < .25 in the bivariate analysis were judiciously selected for inclusion in the moderation analysis, considering them as confounding factors46. P < .05 was indicative of a statistically significant relationship.

Results

Sociodemographic and other characteristics of the sample

Six hundred twenty-nine individuals participated in this study, with a mean age of 29.11 ± 12.22 years (min = 18; max = 70) and 70.9% females. Most participants (73.1%) had attained university-level education, and a significant portion (65.3%) were single. In terms of lifestyle factors, 53.3% owned a car, 29.4% were smokers, and only 7.2% consumed alcohol. The mean household crowding index was 1.09 (SD = 0.52) suggesting that, on average, participants lived in moderately crowded conditions. Financial pressure averaged 4.93 (SD = 2.37), indicating a moderate level of perceived financial strain. Physical activity averaged 25.47 (SD = 20.16). The mean BMI was 24.16 (SD = 4.72), which falls within the normal weight range. Participants reported a mean score of 1.83 (SD = 3.44) for DE symptoms, a mean self-esteem score of 3.51 (SD = 0.98), and a mean GAD-5 score of 15.54 (SD = 12.19) (Table 1).

Bivariate analysis of factors associated with disordered eating symptoms

A lower mean EAT-7 scores was seen in alcohol drinkers compared to non-drinkers (0.12 vs. 0.20; p = .043) (Table 2). Additionally, higher physical activity (r = .15; p < .001) and GAD-5 scores (r = .08; p < .05) were significantly associated with higher EAT-7 scores (more severe DE symptoms) (Table 3).

Moderation analysis

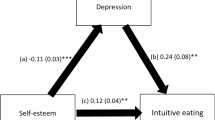

The results of the moderation analysis are summarized in Table 4; Fig. 1. Results were adjusted over the following variables: own a car, alcohol drinking, age, physical activity and financial pressure. Higher GAD-5 scores (Beta = 0.01; p = .004) were significantly associated with higher EAT-7 scores. The interaction generalized anxiety disorder by self-esteem was also significantly associated with EAT-7 scores (Beta = − 0.003; p = .019), indicating that self-esteem moderates the relationship between GAD and DE symptoms. As shown in Table 5, at low (Beta = 0.006; p = .001) and moderate (Beta = 0.003; p = .007) levels of self-esteem, higher GAD-5 scores were significantly associated with higher EAT-7 scores (more severe DE symptoms). In contrast, at high levels of self-esteem, the association was not significant (Beta = 0.001; p = .812), indicating that higher self-esteem may act as a protective factor, reducing the impact of GAD on DE symptoms.

Sensitivity analysis: Moderation analysis taking generalized anxiety disorder as the independent variable, self-esteem as the moderator and disordered eating as the dependent variable, without confounding variables

Higher GAD-5 scores (Beta = 0.01; p = .006) were significantly associated with higher EAT-7 scores. The interaction generalized anxiety disorder by self-esteem was also significantly associated with EAT-7 scores (Beta = − 0.003; p = .021), indicating that self-esteem moderates the relationship between GAD and DE symptoms. At low (Beta = 0.01; p = .002) and moderate (Beta = 0.002; p = .025) levels of self-esteem, higher GAD-5 scores were significantly associated with more severe DE symptoms. In contrast, at high levels of self-esteem, the association was not significant (Beta = 0.001; p = .926).

Discussion

Association between generalized anxiety disorder and disordered eating symptoms

The strong association between the scores from the GAD-5 scale and the EAT-7 that we observed in our research supports the idea that anxiety could be a critical factor associated with inappropriate eating behaviors. Our results are consistent with those of Dicker-Oren et al., who also highlighted an association between daily-life anxiety symptoms and restrained eating21. In a longitudinal study conducted by Lloyd et al., anxiety disorders were found to predict subsequent engagement in fasting for weight loss or to avoid weight gain, a behavior that commonly precedes and is characteristic of anorexia nervosa47. Anxiety, particularly social anxiety, relates to body image dissatisfaction and can intensify the fear of judgment by others48,49,50. Additionally, general anxiety has also been linked to body image concerns. Doumit et al. reported that when general anxiety symptomatology levels were high, body image dissatisfaction was strongly associated with restrained eating51. Individuals with generalized anxiety tend to display perfectionistic traits52, which have been shown to be associated with dietary restraint53. Body image concerns can contribute to unhealthful behaviors as a way to cope with perceived societal pressures. For instance, a study by Leal et al. found that individuals dissatisfied with their bodies and who perceived themselves as overweight were more likely to engage in DE behaviors, such as binge eating, fasting, strict dieting, and the use of diuretics, laxatives, or self-induced vomiting. They were also more prone to unhealthy weight control practices, including eating very little, skipping meals, using food substitutes, taking diet pills, or smoking54,55. In the bivariate analysis, we observed a positive association between physical activity and DE. In prior research, body image concerns have been associated with health-compromising physical activity and eating behaviors56. Another study indicated that compulsive exercise is often used as a strategy to control body weight and shape, particularly in individuals with restricting-type anorexia nervosa57.

Our study observed an inverse relationship between financial pressure and anxiety, contrasting with most existing research58,59,60. However, there are plausible explanations for this finding. Individuals may vary in how they respond to financial stress, and some responses are associated with better functioning. Those who experience sustained financial pressure may develop coping mechanisms (e.g., problem-solving, cognitive restructuring, positive thinking) that enhance resilience in times of difficulty61). Another factor could be social support; it has been reported that if provided, it might act as a moderator of the association between economic hardship and stress, anxiety, and depression62.

Moderation effect of self-esteem

Our study also examined self-esteem as a potential moderator in the relationship between generalized anxiety disorder and DE symptoms. The results indicated that self-esteem may act as a buffer in this association. In other words, while GAD may lead to DE symptoms, self-esteem influences the strength of this relationship. When self-esteem is low, GAD may have a stronger negative impact, increasing the likelihood of developing DE symptoms. Conversely, when self-esteem is high, the effect of GAD on DE may be weaker. Therefore, our findings confirm the initial hypothesis we formulated. They align with those of De Pasquale et al., who proposed and confirmed a similar hypothesis regarding the important role played by self-esteem in the relationship between anxiety and behavioral addictions (EDs and compulsive-buying behavior), which is able to reduce the effect of the former variable on the other variables49. The moderating effect can be explained through coping strategies linked to self-esteem levels. Individuals with high self-esteem tend to evaluate themselves positively and employ adaptive, problem-focused coping strategies. In contrast, those with low self-esteem are prone to negative self-perceptions and adopt maladaptive, emotion-focused coping strategies, often resorting to self-blame, social withdrawal, and avoidance63,64,65. According to Fairburn et al.’s transdiagnostic model of EDs, core low self-esteem contributes to a dysfunctional scheme for self-evaluation. This scheme is characterized by the over-evaluation of achieving perfectionism, which subsequently leads to the over-evaluation of eating, shape, weight and their control. This over-evaluation is hypothesized to lead to strict dieting and other weight control behaviors, which in turn results in either binge eating and compensatory behaviors or low weight and starvation syndrome66. While the correlation between self-esteem and DE did not reach statistical significance in our study, Pelc et al. reported that individuals with lower self-esteem were less content with their appearance and body weight and were at high risk to develop EDs related to dieting, bulimia and food preoccupation, and oral control. Low self-esteem was positively associated with substantial weight loss (over 10 kg) and an increased frequency of uncontrollable binge eating and excessive exercising (more than 60 min per day) to influence their appearance67. Additionally, MacNeil et al. examined whether avoidance coping and poor coping self-efficacy contribute to DE attitudes and behaviors among college students68. Their findings suggested that students with an avoidance coping style and low self-efficacy in coping might be more vulnerable to DE, especially when faced with associated stress. Thus, they proposed that educating students on active, problem-focused coping skills to manage daily challenges in college, along with offering repetitive practice to enhance self-efficacy, could be beneficial in preventing or reducing DE attitudes and behaviors68.

Clinical implications

The findings of this study offer valuable insights for clinical practice. First, the observed association between generalized anxiety disorder and DE symptoms underscores the importance of identifying GAD early to ensure timely interventions that may mitigate the risk of developing DE behaviors. Second, given the moderating role of self-esteem in this relationship, it may be beneficial for clinicians to prioritize the evaluation of self-esteem levels in patients with GAD and eating-related issues. Incorporating self-esteem-building strategies that promote positive coping styles in the face of difficulties may prove helpful in reducing the risk of DE behaviors among anxious individuals. Overall, our findings suggest that a comprehensive approach integrating anxiety management with self-esteem enhancement may be key to preventing or managing DE in vulnerable populations such as Lebanon.

Limitations

Due to the limitations of our study, one should interpret the results with caution. Our research carries the challenges associated with its cross-sectional approach, which, while providing insightful images of relationships at a particular moment, cannot establish causality or temporal sequences of events. Additionally, the low mean age of the participants 29.11 years, the high number of female respondents (70%), and the rate of college-educated respondents (73.1%) suggest that the sample does not reflect the general population of the country since young college-educated women are the demographic most likely to suffer from both anxiety and DE behaviors. It is of note, however, that this limitation is commonly reported with web-based respondent-driven sampling, which tends to over-represent active Internet users who are better educated and of the female gender, possibly leading to problems with representativeness (e.g69,70). , , which may also be exacerbated by the snowball sampling technique. Future studies should enroll an equal number of males and females and individuals from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. Moreover, collecting responses via the Internet relying solely on self-reported data introduces the risk of information bias, potentially resulting from dishonest reporting, memory inaccuracies, or misinterpretation of items. Finally, we did not ask participants whether they were enrolled in a special nutrition program/diet, which could affect DE. Future studies should consider addressing this limitation.

Conclusion

Our findings contribute to the limited literature on the triadic model delineating the moderating role of self-esteem in the association between GAD and DE symptomatology. In contrast to those with higher self-esteem, individuals with lower self-esteem may be more likely to engage in DE when anxiety is present, suggesting that interventions targeting self-esteem could help protect against developing these behaviors. Further studies are needed to support our findings, though our data provides a solid foundation for future investigation on this topic. Future research could gain from combining objective diagnostic methods (i.e., neuropsychological, physical, laboratory evaluations) and longitudinal methodologies, which enable temporal analysis and may provide a deeper comprehension of the causal interconnections among anxiety, self-esteem, and DE behaviors. Raising public awareness about these links can also facilitate early support, promoting mental and physical well-being. Future research should also explore how these relationships manifest in diverse cultural backgrounds, as they may be influenced by sociocultural factors such as Western vs. non-Western ideals of body image71,72. Moreover, future research could build on our findings by exploring factors associated with self-esteem in diverse populations (collectivist vs. individualist cultures)73. Understanding these factors could inform the development of tailored self-esteem enhancement programs that consider the specific cultural or contextual environment of different communities, which then could be integrated into treatment plans for individuals with GAD and DE behaviors, potentially improving therapeutic outcomes.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the ethics committee.

References

Balasundaram, P. & Santhanam, P. Eating Disorders. In: StatPearls. edn. Treasure Island (FL) with ineligible companies. Disclosure: Prathipa Santhanam declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.; (2024).

Galmiche, M., Déchelotte, P., Lambert, G. & Tavolacci, M. P. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 109(5), 1402–1413 (2019).

Melisse, B., de Beurs, E. & van Furth, E. F. Eating disorders in the Arab world: a literature review. J. Eat. Disorders. 8, 1–19 (2020).

van Hoeken, D. & Hoek, H. W. Review of the burden of eating disorders: mortality, disability, costs, quality of life, and family burden. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 33(6), 521–527 (2020).

Auger, N. et al. Anorexia nervosa and the long‐term risk of mortality in women. World Psychiatry 20(3), 448 (2021).

Duriez, P., Goueslard, K., Treasure, J., Quantin, C. & Jollant, F. Risk of non-fatal self‐harm and premature mortality in the three years following hospitalization in adolescents and young adults with an eating disorder: A nationwide population‐based study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 56(8), 1534–1543 (2023).

Auger, N. et al. Anorexia nervosa and the long-term risk of mortality in women. World Psychiatry. 20(3), 448–449 (2021).

Duriez, P., Goueslard, K., Treasure, J., Quantin, C. & Jollant, F. Risk of non-fatal self-harm and premature mortality in the three years following hospitalization in adolescents and young adults with an eating disorder: A nationwide population-based study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 56(8), 1534–1543 (2023).

McGowan, A. & Harer, K. N. Irritable bowel syndrome and eating disorders: a burgeoning concern in Gastrointestinal clinics. Gastroenterol. Clin. 50(3), 595–610 (2021).

McGowan, A. & Harer, K. N. Irritable bowel syndrome and eating disorders: A burgeoning concern in Gastrointestinal clinics. Gastroenterol. Clin. North. Am. 50(3), 595–610 (2021).

Habib, A., Ali, T., Nazir, Z. & Haque, M. A. Unintended consequences of dieting: how restrictive eating habits can harm your health. Int. J. Surg. Open. 60, 100703 (2023).

Krug, I. et al. A meta-analysis of mortality rates in eating disorders: an update of the literature from 2010 to 2024. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2025, 102547 (2025).

Fekih-Romdhane, F., Obeid, S., Malaeb, D., Hallit, R. & Hallit, S. Validation of a shortened version of the eating attitude test (EAT-7) in the Arabic Language. J. Eat. Disorders. 10(1), 1–127. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-022-00651-5 (2022).

Gerges, S., Obeid, S., Hallit, S. Pregnancy through the Looking-Glass: correlates of disordered eating attitudes among a sample of Lebanese pregnant women. BMC Psychiatry 23(1), 699. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05205-w (2023).

Lombardo, M. et al. Gender differences in taste and foods habits. Nutr. Food Sci. 50(1), 229–239 (2020).

Drewnowski, A. & Shultz, J. M. Impact of aging on eating behaviors, food choices, nutrition, and health status. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 5(2), 75 (2001).

Conklin, A. I. et al. Social relationships and healthful dietary behaviour: evidence from over-50s in the EPIC cohort, UK. Soc. Sci. Med. 100(100), 167–175 (2014).

Nishinakagawa, M. et al. Influence of education and subjective financial status on dietary habits among young, middle-aged, and older adults in Japan: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public. Health. 23(1), 1230 (2023).

Munir, S. & Takov, V. Generalized anxiety disorder. StatPearls [Internet] StatPearls Publishing (2022).

Munir, S. & Takov, V. Generalized Anxiety Disorder. In StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Veronica Takov declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies (2024).

Dicker-Oren, S., Gelkopf, M. & Greene, T. Anxiety and restrained eating in everyday life: an ecological momentary assessment study. J. Affect. Disord. 362, 543–551 (2024).

Godart, N. T., Flament, M. F., Lecrubier, Y. & Jeammet, P. Anxiety disorders in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: co-morbidity and chronology of appearance. Eur. Psychiatry. 15(1), 38–45 (2000).

Hasler, G. et al. The associations between psychopathology and being overweight: a 20-year prospective study. Psychol. Med. 34(6), 1047–1057 (2004).

Mazzeo, S. E., Slof, R. M., Tozzi, F., Kendler, K. S. & Bulik, C. M. Characteristics of men with persistent thinness. Obes. Res. 12(9), 1367–1369 (2004).

Dale, K. L. The relationship between eating attitudes, social anxiety, body-satisfaction and self-esteem in young women with and without disordered eating attitudes (1995).

Du, H., King, R. B. & Chi, P. Self-esteem and subjective well-being revisited: the roles of personal, relational, and collective self-esteem. PloS One. 12(8), e0183958–e0183958 (2017).

Mann, M., Hosman, C. M. H., Schaalma, H. P. & de Vries, N. K. Self-esteem in a broad-spectrum approach for mental health promotion. Health Educ. Res. 19(4), 357–372 (2004).

Fekih-Romdhane, F., Sawma, T., Obeid, S. & Hallit, S. Self-critical perfectionism mediates the relationship between self-esteem and satisfaction with life in Lebanese university students. BMC Psychol 11(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01040-6 (2023).

Awad, E., Hallit, S. & Obeid, S. Does self-esteem mediate the association between perfectionism and mindfulness among Lebanese university students? BMC Psychol. 10(1), 256 (2022).

Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I. & Vohs, K. D. Does high Self-Esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles?? Psychol. Sci. 4(1), 1–44 (2003).

Farran, N. Mental health in Lebanon: tomorrow’s silent epidemic. Mental Health Prev. 24, 200218 (2021).

Pescatori, A., Bogmans, C. & Prifti, E. Income Versus Prices: How Does the Business Cycle Affect Food (In)-Security? In. St (Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, 2021).

Zeeni, N., Safieddine, H. & Doumit, R. Eating disorders in Lebanon: directions for public health action. Community Ment Health J. 53(1), 117–125 (2017).

Afifi-Soweid, R. A., Najem Kteily, M. B. & Shediac-Rizkallah, M. C. Preoccupation with weight and disordered eating behaviors of entering students at a university in Lebanon. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 32(1), 52–57 (2002).

Tamim, H. et al. Risky weight control among university students. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 39(1), 80–83 (2006).

Fritz, M. S. & MacKinnon, D. P. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychol. Sci. 18(3), 233–239 (2007).

Melki, I. S., Beydoun, H. A., Khogali, M., Tamim, H. & Yunis, K. A. National collaborative perinatal neonatal N: household crowding index: a correlate of socioeconomic status and inter-pregnancy spacing in an urban setting. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 58(6), 476–480 (2004).

El Zouki, C-J. et al. Arabic validation of the incharge financial Distress/Well-being scale (IFDFW) and the new Single-Item financial stress scale (SIFiS). https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-5911447/v1 (2025).

Zierle-Ghosh, A. & Jan, A. Physiology, Body Mass Index. In: StatPearls. edn. Treasure Island (FL) ineligible companies. Disclosure: Arif Jan declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies (2025).

Assaf, M. et al. Arabic Translation and Psychometric Testing of the Physical Activity Index (PAI). https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-5945662/v1 (2025).

Sawma, T. et al. Psychometric properties of the Arabic generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-5) in a non-clinical sample of Arabic-speaking adults. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4984547/v1 (2024).

Garfinkel, P. E. & Newman, A. The eating attitudes test: Twenty-five years later. Eat. Weight Disorders - Stud. Anorexia Bulimia Obes. 6(1), 1–21 (2001).

Fekih-Romdhane, F. et al. Validity and reliability of the Arabic version of the self-report single-item self-esteem scale (A-SISE). BMC Psychiatry 23(1), 351. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04865-y (2023).

Hair, J. F. Jr et al. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook, 1st 2021;1st 2021; Edn (Springer International Pub, 2021).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction To Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach 3rd edn (Guilford, 2022).

Bursac, Z., Gauss, C. H., Williams, D. K. & Hosmer, D. W. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol. Med. 3, 17 (2008).

Lloyd, E. C., Haase, A. M., Zerwas, S. & Micali, N. Anxiety disorders predict fasting to control weight: a longitudinal large cohort study of adolescents. Eur. Eat. Disorders Rev. 28(3), 269–281 (2020).

Menatti, A. R., DeBoer, L. B. H., Weeks, J. W. & Heimberg, R. G. Social anxiety and associations with eating psychopathology: mediating effects of fears of evaluation. Body Image. 14, 20–28 (2015).

De Pasquale, C. et al. The roles of anxiety and self-esteem in the risk of eating disorders and compulsive buying behavior. Int J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 19(23) (2022).

Al-Musharaf, S. et al. Factors of body dissatisfaction among Lebanese adolescents: the indirect effect of self-esteem between mental health and body dissatisfaction. BMC Pediatr. 22(1), 302 (2022).

Doumit, R., Zeeni, N., Sanchez Ruiz, M. J. & Khazen, G. Anxiety as a moderator of the relationship between body image and restrained eating. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care. 52(4), 254–264 (2016).

Handley, A. K., Egan, S. J., Kane, R. T. & Rees, C. S. The relationships between perfectionism, pathological worry and generalised anxiety disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 14, 1–8 (2014).

McLaren, L., Gauvin, L. & White, D. The role of perfectionism and excessive commitment to exercise in explaining dietary restraint: replication and extension. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 29(3), 307–313 (2001).

Leal, G. V. S., Philippi, S. T. & Alvarenga, M. S. Unhealthy weight control behaviors, disordered eating, and body image dissatisfaction in adolescents from São Paulo, Brazil. Brazilian J. Psychiatry. 42(3), 264–270 (2020).

Leal, G., Philippi, S. T. & Alvarenga, M. D. S. Unhealthy weight control behaviors, disordered eating, and body image dissatisfaction in adolescents from Sao Paulo, Brazil. Braz J. Psychiatry. 42(3), 264–270 (2020).

Jankauskiene, R., Baceviciene, M., Pajaujiene, S. & Badau, D. Are adolescent body image concerns associated with health-compromising physical activity behaviours? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 16(7), 1225 (2019).

Dalle Grave, R., Calugi, S. & Marchesini, G. Compulsive exercise to control shape or weight in eating disorders: prevalence, associated features, and treatment outcome. Compr. Psychiatr. 49(4), 346–352 (2008).

Ryu, S. & Fan, L. The relationship between financial worries and psychological distress among US adults. J. Fam. Econ. Issues. 44(1), 16–33 (2023).

Chai, L. Financial strain and psychological distress among middle-aged and older adults: a moderated mediation model. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work. 66(8), 1120–1132 (2023).

Nasr, R. et al. Financial insecurity and mental well-being: experiences of parents amid the Lebanese economic crisis. BMC Public. Health. 24(1), 3017 (2024).

Perzow, S. E., Bray, B. C. & Wadsworth, M. E. Financial stress response profiles and psychosocial functioning in low-income parents. J. Fam. Psychol. 32(4), 517 (2018).

Viseu, J. et al. Relationship between economic stress factors and stress, anxiety, and depression: moderating role of social support. Psychiatry Res. 268, 102–107 (2018).

Doron, J., Thomas-Ollivier, V., Vachon, H. & Fortes-Bourbousson, M. Relationships between cognitive coping, self-esteem, anxiety and depression: A cluster-analysis approach. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 55(5), 515–520 (2013).

Li, W. et al. Reciprocal relationships between self-esteem, coping styles and anxiety symptoms among adolescents: between-person and within-person effects. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Mental Health. 17(1), 21 (2023).

Li, W. et al. Reciprocal relationships between self-esteem, coping styles and anxiety symptoms among adolescents: between-person and within-person effects. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment Health. 17(1), 21 (2023).

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z. & Shafran, R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a transdiagnostic theory and treatment. Behav. Res. Ther. 41(5), 509–528 (2003).

Pelc, A., Winiarska, M., Polak-Szczybylo, E., Godula, J. & Stepien, A. E. Low self-esteem and life satisfaction as a significant risk factor for eating disorders among adolescents. Nutrients 15(7) (2023).

MacNeil, L., Esposito-Smythers, C., Mehlenbeck, R. & Weismoore, J. The effects of avoidance coping and coping self-efficacy on eating disorder attitudes and behaviors: A stress-diathesis model. Eat. Behav. 13(4), 293–296 (2012).

Kelfve, S., Kivi, M., Johansson, B. & Lindwall, M. Going web or staying paper? The use of web-surveys among older people. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 20, 1–12 (2020).

Lehdonvirta, V., Oksanen, A., Räsänen, P. & Blank, G. Social media, web, and panel surveys: using non-probability samples in social and policy research. Policy Internet. 13(1), 134–155 (2021).

Hofmann, S. G. & Hinton, D. E. Cross-cultural aspects of anxiety disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 16(6), 450 (2014).

Zeeni, N., Gharibeh, N. & Katsounari, I. The influence of Sociocultural factors on the eating attitudes of Lebanese and Cypriot students: a cross-cultural study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 26(Suppl 1), 45–52 (2013).

Tafarodi, R. W. & Swann, W. B. Jr Individualism-collectivism and global self-esteem: evidence for a cultural trade-off. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 27(6), 651–672 (1996).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FFR, SO and SH designed the study; DM, FS and MD collected the data, RA and MA drafted the manuscript; SH carried out the analysis and interpreted the results; SEK reviewed the final manuscript; all authors gave their consent.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Psychiatric Hospital of the Cross Ethics and Research Committee approved this study protocol (HPC-032-2022). A written informed consent was considered obtained from each participant when submitting the online form. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdallah, R., Assaf, M., Malaeb, D. et al. The association between generalized anxiety disorder and disordered eating symptoms among Lebanese adults with the moderating effect of self esteem. Sci Rep 15, 17850 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02985-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-02985-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Bidirectional associations between anxiety and eating disorder symptoms in adolescence: the moderating role of childhood household dysfunction

Journal of Eating Disorders (2025)

-

Mediating effect of food disgust between depression/anxiety and avoidant restrictive eating

Journal of Eating Disorders (2025)