Abstract

The worldwide health crisis caused by obesity is not only a concern for individuals, but its impact may extend to future generations. Studies have indicated that parental obesity can influence offspring’s metabolic and reproductive health. However, the sex-specific contribution of parental obesity on the metabolic and reproductive health of their offspring is not fully explained. In the present study, we used a Cafeteria diet (Caf) to induce obesity and investigated the possible intergenerational implications of parental obesity on the offspring. Sprague-Dawley rats were fed either a rodent standard chow or a Caf diet, which included a variety of energy-dense human snacks, for 20 weeks. Offspring (F1 generation) were generated by breeding female rats from both diet groups with males of control and Caf diet groups. Parents on the Caf diet showed a marked increase in body weight and exhibited adverse changes in their cholesterol/HDL ratio, triglyceride/HDL ratio, and glucose tolerance. Notably, F0 males were more severely affected than females. Reproductive indices were affected by both maternal and paternal obesity with reduced fertility and increased stillbirth. Furthermore, altered levels of circulatory progesterone, testosterone, and estradiol showed the impaired hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and the disturbed onset of puberty. Both male and female offspring showed hyperglycemia and imbalances in lipid levels, particularly influenced by maternal obesity. The results indicate that obesity may have profound effects, potentially leading to metabolic and reproductive issues in future generations. This study highlights the importance of parental health and diet choices on the well-being of their children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity prevalence has been steadily increasing over the past few decades and is associated with various health risks, including an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancers, and other chronic conditions1. The rise in obesity is often attributed to factors such as sedentary lifestyles, unhealthy diets high in processed foods, and genetic predisposition. Childhood obesity is of particular concern as it leads to chronic health disorders in adulthood. Obesity can have significant effects on reproductive health in both men and women. In males, obesity is known to cause insulin resistance, hormonal imbalance, increased scrotal temperature, reduced quality and quantity of sperm, and erectile dysfunction2,3. Whereas, insulin resistance, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), menstrual irregularities, reduced fertility, low success rates in assisted reproductive technology (ART), complications in pregnancy, and risk of miscarriage are reported in obese female4,5.

Obesity during the perinatal period predisposes the foetus to various metabolic disturbances in utero that reflect on offspring health6,7,8. Studies have shown that maternal obesity increases the risk of obesity, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases in offspring9,10. A cross-sectional study of Chinese children and adolescents reported that maternal overweight has a stronger association with an increased risk of metabolic syndrome in offspring11. Additionally, paternal obesity has been reported to predispose offspring to obesity and other metabolic disorders12,13. The study of parental obesity and its impact on offspring is a critical area to explore, particularly, in understanding the effect of metabolic disorders on reproductive health.

Though obesity is considered multifactorial, diet and food habits play a major role in obesity development. Cafeteria (Caf) diet refers to a type of diet that includes energy-dense, highly palatable foods with poor nutritional quality14. Unlike other diet-induced obesity (DIO) models, the Caf diet model replicates the texture and flavour of food that promotes hyperphagia. Caf diet leads to obesity, metabolic dysregulation, liver disorders, cardiovascular disorders, and diabetes15,16. Maternal obesity induced by the Caf diet has been reported to increase body weight, triglyceride, and cholesterol in the blood and impair glucose tolerance in the offspring and Caf diet consumption during lactation is shown to exhibit thin outside fat inside phenotype where a normal BMI is observed with disproportionate fat deposition and increased risk of metabolic disorder in female offspring17,18.

The influence of parental obesity on the health of offspring is a significant concern, as it has been linked to an increased risk of metabolic disorders and reproductive health. These associations are thought to be mediated by epigenetic mechanisms of foetal programming, highlighting the importance of parental health at conception. The existing studies highlight the individual effects of maternal and paternal obesity on progeny, but there is a compelling need to investigate the combined effects when both parents are obese. Hence, this study was designed to explore the intergenerational effect of parental obesity on the metabolic and reproductive health of male and female offspring using a Caf diet-induced obese model.

Materials and methods

Animals, feeding procedures, and group separation

Sprague-Dawley rats (21 days old) were housed in polypropylene cages and maintained under optimal conditions (22–24 °C and 12 h light/dark cycles) in the Central Animal House Facility, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Madras, Chennai, India. All the experiments were approved by ‘The Institutional Animal Ethical Committee’, University of Madras, and were performed according to the guidelines of ‘The Committee for Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals’ (CCSEA), India (IAEC No.:02/04/2022). This study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. Euthanasia of animals was performed in compliance with CCSEA guidelines by administration of an overdose of sodium thiopentone (130 mg/kg, IV) which led to respiratory distress and death.

The rats were grouped as follows: control male (Con-M; n = 16), control female (Con-F; n = 18), Cafeteria diet male (Caf-M; n = 16), and Cafeteria diet female (Caf-F; n = 18). Control group rats were fed with rodent standard chow (RSC) and the rats in the Caf group were fed various energy-dense foods available in local supermarkets and Cafeterias along with RSC. The Caf diet’s nutritional details were outlined in our earlier research19. Three different types of human snacks were provided and the variety of snacks was changed daily to maintain the palatability. The animals received purified drinking water ad libitum and ensured that not more than 2 animals were housed in a cage (Con and Caf male − 8 cages/ group; Con and Caf female – 9 cages/group). The feed intake (RSC and Caf) was measured daily by weighing the difference in the initial feed provided and leftovers in the cage the next day. The feed regimen was followed for 20 weeks after which the animals in the Caf group were provided only with RSC.

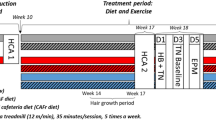

A batch of F0 female rats (n = 12) from both the groups (Con-F and Caf-F) were interbred with Con-M (n = 6) and Caf-M (n = 6) animals in the proestrus phase to generate F1 offspring and another set of F0 female rats (n = 6) were euthanized in the diestrus phase. The mating scheme among the groups is represented in Fig. 1. Briefly, Con-F X Con-M yielded F1 Con, Con-F X Caf-M yielded F1 PO, Caf-F X Con-M yielded F1 MO and Caf-F X Caf-M yielded F1 OO. The male rats in the Con-M and CAF-M groups were euthanized soon after the mating protocol. After weaning of the pups (21 days of age), the male and female rats were housed separately and grouped as F1 Con, F1 PO, F1 MO, and F1 OO. The number of pups per dam was culled to 7 irrespective of gender, to avoid inconsistency in feeding during the lactation period between control and obese groups. All the F1 rats were fed with RSC and the feed intake was recorded as mentioned earlier. In this study, the offspring were not given the Caf diet. This strategy aimed to distinguish the programmed effects of parental dietary habits from the offspring’s diet. This approach allows for a clearer analysis of the transgenerational impact of dietary choices, focusing on the potential epigenetic changes passed from the parents to their offspring, rather than the immediate dietary effects.

Experimental design-treatment protocol and mating scheme. Sprague-Dawley rats (21 days old) were grouped as control male (Con-M), control female (Con-F), cafeteria diet male (Caf-M), and cafeteria diet female (Caf-F). Control group rats were fed with rodent standard chow and the rats in Caf group were fed with ultra-processed human snacks for 20 weeks. A batch of F0 female rats from both the groups (Con-F and Caf-F) were interbred between the groups in the proestrus phase to generate F1 offspring. The offspring were maintained on standard chow and euthanized after three months. F1 CO—F1 Offspring born to Control mother and control father; F1 MO—F1 Maternal obese- F1 Offspring born to obese mother and control father; F1 PO—F1 Paternal obese—F1 Offspring born to control mother and obese father; F1 OO—F1 Parental obese- F1 Offspring born to obese father and obese mother.

Both male and female offspring rats were euthanized after three months. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture and glucose level was measured using CONTOUR ® PLUS blood glucose test strips (Ascensia diabetes care, India). The serum was separated by centrifugation and the fat depots (visceral and subcutaneous fat pads) were collected and weighed. Relative fat weight was calculated using the formula (Total fat pad weight / Body weight) x 100.

Analysis of metabolic parameters

Energy intake, body weight gain, Lee index, and Cholesterol: HDL, and Triglycerides: HDL were calculated in both F0 and F1 generations. Energy intake was calculated based on the nutritional composition of the RSC and Caf diet according to the manufacturer’s information. The body weight was recorded weekly and the body weight gain was calculated as the difference between final body weight and initial body weight. Lee index was calculated using the formula (cube root of body weight) / (naso-anal length) x 1000. The day of vaginal opening in the female rats and the day of preputial separation in the male rats were accounted as pubertal onset. Serum levels of total cholesterol (Oxidase/peroxidase method), HDL (direct clearance), and triglycerides (GPO/enzymatic method) were measured by spectrophotometry using a BA 400 biochemistry analyzer (Biosystems, Spain). Serum leptin was measured using an ELISA kit specific for rat samples procured from Raybiotech, GA, USA. An oral glucose tolerance test (GTT) was performed in the 20th week of the dietary period in F0 animals and after 80 days in F1 animals by following the method of Pedro et al.., and the area under the curve (AUC) was plotted20. Briefly, the rats were fasted overnight and fed with glucose solution (2 g/kg in distilled water) orally using a gavage needle. Blood was collected by tail prick and glucose levels were measured at 0-, 60-, 120-, and 180 min using glucose strips.

Analysis of reproductive parameters

Pubertal onset was recorded in both F0 and F1 rats. The day of vaginal opening in the female rats and the day of preputial separation in the male rats were accounted as pubertal onset. Three consecutive estrous cycles were checked by vaginal smear from the 19th week of the food exposure in F0 rats and at 90 days of age in F1 rats. Reproductive hormones such as progesterone, estradiol, and testosterone were measured in the serum by chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA) using Architect i1000sr (Abbott, Il, USA). The reproductive indices were calculated as mentioned in Table 1. The litter size, body weight of pups at birth, and stillbirth were recorded.

Statistical analyses

The data of F0 animals were analysed by Student’s t-test. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the inter-group differences in F1 animals. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc correction was used to compare the paternal and maternal effects (main effects) and interaction on the F1 generation. Analysis of repeated measures was carried out to check the difference in feed intake, energy intake and GTT between the groups. All the analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism, V.8.4.3, and the results are expressed as mean ± SEM with p < 0.05 compared with the respective control.

Results

Effect of cafeteria diet intake on feed intake and metabolic parameters in F0 rats

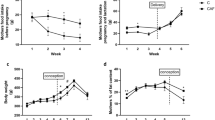

The feed (Fig. 2a) and calorie intake (Fig. 2b) significantly increased in both male and female Caf group animals from the first week. This is reflected in the increased body weight and Lee index in Caf males and females (Table 2). The relative fat weight, and the ratio of cholesterol: HDL and triglyceride: HDL was increased in rats fed with a Cafeteria diet (Table 2). GTT revealed that the rats in the Caf group were hyperglycaemic at all time points of measurement (Fig. 2c, e) with increased AUC in the Caf group (Fig. 2d, f; Table 2), indicating glucose intolerance.

Cafeteria diet intake alters feed intake and metabolic parameters in F0 rats. (a) Feed intake, (b) Calorie intake, (c) Glucose tolerance test—F0 Male, (d) Area under the curve (AUC)–GTT, F0 male, (e) Glucose tolerance test—F0 Female, (f) Area under the curve (AUC)–GTT, F0 female. Data are represented as mean ± SEM of 12 animals. *Significant difference at p < 0.05, compared with respective control.

Effect of cafeteria diet-induced obesity on serum hormones, pubertal onset, and estrous cycle in F0 rats

Both male and female rats in the Caf group were hyperleptinemic compared with the control group (Fig. 3a, b). However, the alterations in the serum levels of reproductive hormones were found to be sex-specific. In Caf males, hypoprogesteronemia (Fig. 3c), hypotestosteronemia (Fig. 3e), and hyperestrogenemia (Fig. 3g) were observed compared with the control. Whereas in Caf females, hyperprogesteronemia (Fig. 3d), hypertestosteronemia (Fig. 3f), and hypoestrogenemia (Fig. 3h) were detected. The preputial separation (Fig. 3i) and vaginal opening (Fig. 3j) were delayed in the Caf group rats. Estrous cycle was extended in the Caf female rats with significant lengthening of the metestrus phase (Fig. 3k).

Cafeteria diet-induced obesity alters serum hormones, pubertal onset, and estrous cycle in F0 rats. (a) Serum Leptin—F0 Male, (b) Serum Leptin—F0 Female, (c) Serum progesterone—F0 Male, (d) Serum progesterone—F0 Female, (e) Serum Testosterone—F0 Male, (f) Serum Testosterone- F0 Female, (g) Serum Estradiol—F0 Male, (h) Serum Estradiol—F0 Female, (i) Preputial separation—F0 Male, (j) Vaginal opening—F0 Female, (k) Estrous cycle—F0 Female. Data are represented as mean ± SEM of 12 animals. *Significant difference at p < 0.05 compared with respective control.

Effect of cafeteria diet-induced obesity on reproductive indices

In our study, obese rats showed a reduced fertility index, with scores of 75%, 67%, and 75% in the MO, PO, and OO groups, respectively (Table 3). The conception index also significantly decreased in the obese groups, with the OO group having the lowest rate at 23%, indicating a delay in the time to conceive, if both parents are obese (Table 3). Reduced litter size was observed in MO, PO, and OO groups, with a significant effect due to paternal obesity (p = 0.0004), maternal obesity (p = 0.0264), and parental obesity (p = 0.0264) (Table 4). The pups of obese parents were macrosomic (body weight above 90th percentile compared with control) when either of the parents was obese (p < 0.0001) and had a significant effect due to interaction (p = 0.0135) (Table 4). Stillbirths were observed in PO and OO groups at the rate of 52% and 48%, respectively (Table 4).

Effect of parental obesity on metabolic parameters and serum leptin of adult F1 female offspring

The body weight, Lee index, cholesterol: HDL, and triglyceride: HDL levels of female offspring increased significantly in MO, PO, and OO groups compared with CO animals. It was influenced by the main effects i.e., Maternal obesity and paternal obesity but not due to the interaction except Lee index (Table 5). The rats were hyperglycemic (Table 5) and GTT revealed that blood glucose level was increased at all time points in the MO, PO, and OO groups compared with control indicating glucose intolerance (Fig. 4b, d). Also, the rats were hyperleptinemic (Fig. 4f) indicating that parental obesity alters the metabolism of female offspring on RSC.

Parental obesity caused glucose intolerance and hyperleptinemia in adult F1 offspring rats. (a) Glucose tolerance test–F1 Male, (b) Glucose tolerance test–F1 Female. (c) Area under the curve (AUC)–GTT, F1 male, (d) Area under the curve (AUC)–GTT, F1 Female, (e) Serum Leptin- F1 Male, (f) Serum Leptin- F1 Female. Data are represented as mean ± SEM of 12 animals. *Significant difference at p < 0.05, compared with respective control.

Effect of parental obesity on metabolic parameters and serum hormones of adult F1 male offspring

The body weight and Lee index of the male offspring born to obese parents were significantly increased and influenced by the main effects (Table 6). The level of cholesterol: HDL was influenced by the paternal obesity and interaction, but not due to the maternal obesity. However, the intergroup comparison revealed a significant increase in the cholesterol: HDL level in MO, PO, and OO groups compared with the control animals. The rats born to obese parents were hypertriglyceridemic and hyperglycemic, and were influenced by the paternal effect, maternal effect, and interactive effect (Table 6). GTT results revealed an increase in the blood glucose at 60, 120, and 180 min (Table 6) and AUC in animals born to obese parents (Fig. 4c). However, the AUC was not influenced by the interaction (Table 6). Male offspring born to obese parents had a significant rise in the level of leptin in the serum (Fig. 4e).

Effect of parental obesity on pubertal onset and serum sex hormones of adult F1 offspring

In the male offspring born to obese parents, early separation of preputium was observed (Fig. 5a). Similarly, in the female offspring, early vaginal opening was observed (Fig. 5b). These results indicate precocious puberty. The male rats in the MO, PO, and OO groups exhibited hypoprogesteronemia, hypotestosteronemia, and hyperestrogenemia compared with the CO group (Fig. 5d–f). Though the estrous cycle increased in length in MO, PO, and OO groups, a significant difference was observed in the PO group animals compared to the control group (Fig. 5c). Hyperprogesteronemia, hypertestosteronemia, and hypoestrogenemia were observed in the F1 female offspring born to obese parents (Fig. 5g–i).

Parental obesity leads to precocious puberty and altered serum sex hormone levels in adult F1 offspring rats. (a) Preputial separation–F1 Male, (b) Vaginal opening—F1 Female, (c) Estrous cycle—F1 Female, (d) Serum progesterone–F1 Male, (e) Serum Testosterone- F1 Male, (f) Serum Estradiol- F1 Male, (g) Serum progesterone–F1 Female, (h) Serum Testosterone- F1 Female, (i) Serum Estradiol- F1 Female. Data are represented as mean ± SEM of 12 animals. *significant difference at p < 0.05 compared with respective control.

Discussion

With the prevalence of obesity globally having reached epidemic proportions, it affects health in several areas such as metabolism, cardiovascular health, and fertility. Diet is crucial in obesity development, with Caf diets being a significant source given its high-calorie content and palatability. This study aims to investigate the effects of Caf diet-induced obesity on sex-specific metabolic parameters and subsequent reproductive outcomes in the offspring rats.

Caf diet is attributed to its palatability and, the calorie-rich human foods caused a significant rise in both feed intake and energy intake compared to control diets. This is consistent with previous work19,21 demonstrating the hyperphagic response to palatable food, which in turn leads to body weight gain and a higher Lee index. In F0 rats, Caf diet consumption led to hyperlipidemia, glucose intolerance, and hyperleptinemia showcasing the hallmark responses of obesity.

To identify the contribution of maternal or paternal obesity on offspring’s reproductive health, Caf diet-induced obese F0 rats were crossed with either control or Caf rats, and the F1 offspring rats were used for further investigation. This approach can provide unique insight into the potential epigenetic and genetic factors that may influence the offspring’s reproductive health. The Developmental Origins of Health and Diseases (DoHaD) concept highlights the importance of maternal and paternal nutritional insults during the preconception or periconceptional period, which may permanently alter the offspring’s epigenome, leading to adult metabolic disorders. Epidemiological and experimental evidence links parental nutritional status to reproductive outcomes in offspring.

In our study, obese rats showed a reduced fertility index and conception index in the obese groups which was similar to previous studies22,23. Clinical studies reported that obese women are prone to recurrent miscarriages and the fetus has an increased risk of large to gestational age (LGA)24,25. The reduction in the litter size could be due to a decrease in the level of pre-gestational estradiol26. Maternal obesity induced by a cafeteria diet has been reported to result in macrosomic pups22,23,27,8. However, conflicting results are observed by a few other research groups where maternal obesity either decreased the neonatal birth weight or showed no significant changes in birth weight7,28,29. The results of the present study corroborate with the results in humans where parental obesity leads to macrosomia in offspring30,31,32.

Maternal obesity has been associated with an increased risk of stillbirth33,34,35. However, no stillbirths were observed in the MO group of our study. The absence of stillbirths in the MO group in our study is intriguing, especially considering the established impact of maternal obesity on the uterine environment and embryonic development. Research suggests that paternal obesity can affect fetal growth parameters and placental development, potentially leading to adverse pregnancy outcomes36. Our finding highlights the sex-specific effects of parental obesity on the well-being of the offspring. These insights are valuable for understanding the multifactorial nature of macrosomia and its inheritance patterns.

We further checked the metabolic parameters of offspring three months after weaning. The body weight and Lee index were significantly increased in both male and female rats born to obese parents, even when the offspring consumed a standard diet. This highlights the potential for parental health and nutrition to influence the well-being of the next generation. Though hyperglycemia and impaired glucose tolerance were recorded in both male and female offspring, maternal obesity had a greater impact on the glycaemic status of offspring male rats (p = 0.0024) compared to paternal obesity (p = 0.0311). Hyperleptinemia was observed in all the offspring animals compared to their respective control, irrespective of sex which could promote glucose intolerance37.

The profound effect of Caf diet-induced obesity and associated metabolic disruption often led to defective Hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. The decreased levels of serum progesterone in both F0 and F1 male rats compared with respective control groups was consistent with the previous studies revealing a negative correlation between male obesity and progesterone levels in circulation38,39. Decreased testosterone levels in obese male rats may be influenced by increased leptin, which is known to inhibit testosterone synthesis40,41. We suggest that decreased levels of progesterone could be the reason as it is the precursor for testosterone. Additionally, the increased levels of estradiol in the serum of F0 and F1 male rats could be attributed to peripheral conversion of testosterone in adipose tissues due to enhanced aromatase activity42,43. The observed hormonal changes in both parents and male offspring indicate a complex interplay between various factors. The increased estradiol further shunts the testosterone production via the HPG axis.

Female rats, on the contrary, were observed to exhibit hyperprogesteronemia, hypertestoteronemia, and hypoestrogenemia. Increased levels of testosterone in circulation in obesity and insulin resistance have been reported in female19,44,45. Our finding is similar to studies on obese patients and experimental diet-induced obesity models, where estradiol levels were decreased in obese condition19,46,47,48. These alterations in the HPG axis resulted in the extended estrous cycle in F0 and F1 PO group animals.

The onset of puberty is a complex process influenced by various factors, including hormonal balance and the HPG axis. Disruptions in this axis can lead to early or delayed pubertal onset. We found that the Caf diet delayed the onset of puberty in the F0 generation rats and conversely, the offspring of these F0 obese rats showed earlier pubertal onset. This finding highlights the complex interplay between genetics, parental health, and diet, which can have varying effects across generations. In females, precocious puberty is widely reported, influenced by maternal obesity and leptin levels. Ribeiro et al.. reported that childhood obesity leads to early sexual maturation in both males and females49. However, the reports on pubertal onset in obese males are conflicting. Busch et al.. reported earlier testicular enlargement in obese boys compared to those with normal weight50.

It is suggested that maternal obesity may confer a greater risk of obesity and metabolic disorders in offspring, through maternal nutritional and metabolic status during critical periods such as gestation and lactation. Hormonal imbalances stemming from maternal obesity could also adversely affect the reproductive health of the offspring. Paternal obesity, on the other hand, may influence offspring through genetic and possibly epigenetic mechanisms, altering the risk profile for various health outcomes. A comprehensive understanding of both genetic predisposition and the intrauterine environment is crucial for comprehending the maternal and paternal nutritional insults during the preconception period on the reproductive health of children born to obese parents.

This study investigates the intergenerational effects of parental obesity on metabolic and reproductive health in offspring, using a cafeteria diet model. It is the first to examine both the individual and combined impacts of paternal and maternal obesity on the health of male and female offspring. Our findings reveal that pre-conceptional obesity in both parents leads to adverse reproductive outcomes and metabolic disturbances in offspring, with these effects being more pronounced when both parents are obese. The impact of parental obesity on offspring is observed regardless of gender; however, suboptimal intrauterine conditions seem to amplify the effects of maternal obesity.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its Supplementary Information file.

Abbreviations

- Caf:

-

Cafeteria diet

- Con:

-

Control

- HDL:

-

High density lipoprotein

- RSC:

-

Rodent standard chow

- ART:

-

Assisted reproductive technology

- DIO:

-

Diet-induced obesity

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- SEM:

-

Standard error of mean

- GTT:

-

Glucose tolerance test

- AUC:

-

Area under curve

- GPO:

-

Glycerol-3-phosphate

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- MO:

-

Maternal obese

- PO:

-

Paternal obesity

- OO:

-

Parental obesity

- LGA:

-

Large to gestational age

- HPG:

-

Hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal axis

- PCOS:

-

Polycystic ovarian syndrome

References

Alkhatib, A. & Obita, G. Childhood obesity and its comorbidities in High-Risk minority populations: prevalence, prevention and lifestyle intervention guidelines. Nutrients 16, 1730 (2024).

Lenart-Lipińska, M., Łuniewski, M., Szydełko, J. & Matyjaszek-Matuszek, B. Clinical and therapeutic implications of male obesity. J. Clin. Med. 12, 5354 (2023).

Venigalla, G. et al. Male obesity: associated effects on fertility and the outcomes of offspring. Andrology https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.13552 (2023).

Maxwell, C. V. et al. Management of obesity across women’s life course: FIGO best practice advice. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 160, 35–49 (2023).

Gautam, D. et al. The challenges of obesity for fertility: a < scp > figo literature review. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 160, 50–55 (2023).

Buckley, A. J. et al. Altered body composition and metabolism in the male offspring of high fat–fed rats. Metabolism 54, 500–507 (2005).

Desai, M. et al. Maternal obesity and high-fat diet program offspring metabolic syndrome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 211, 237e1–237e13 (2014).

Samuelsson, A. M. et al. Diet-Induced obesity in female mice leads to offspring hyperphagia, adiposity, hypertension, and insulin resistance. Hypertension 51, 383–392 (2008).

Godfrey, K. M. et al. Influence of maternal obesity on the long-term health of offspring. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 5, 53–64 (2017).

Williams, C. B., Mackenzie, K. C. & Gahagan, S. The effect of maternal obesity on the offspring. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 57, 508–515 (2014).

Yang, Z. et al. Relationship between parental overweight and obesity and childhood metabolic syndrome in their offspring: result from a cross-sectional analysis of parent–offspring trios in China. BMJ Open. 10, e036332 (2020).

Freeman, E. et al. Preventing and treating childhood obesity: time to target fathers. Int. J. Obes. 36, 12–15 (2012).

Lecomte, V., Maloney, C. A., Wang, K. W. & Morris, M. J. Effects of paternal obesity on growth and adiposity of male rat offspring. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab.. 312, E117–E125 (2017).

Lalanza, J. F. & Snoeren, E. M. The cafeteria diet: A standardized protocol and its effects on behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 122, 92–119 (2021).

Sampey, B. P. et al. Cafeteria diet is a robust model of human metabolic syndrome with liver and adipose inflammation: comparison to High-Fat diet. Obesity 19, 1109–1117 (2011).

de la Garza, A. L. et al. Characterization of the cafeteria diet as simulation of the human Western diet and its impact on the lipidomic profile and gut microbiota in obese rats. Nutrients 15, 86 (2022).

Jacobs, S. et al. The impact of maternal consumption of cafeteria diet on reproductive function in the offspring. Physiol. Behav. 129, 280–286 (2014).

Pomar, C. A. et al. Maternal consumption of a cafeteria diet during lactation in rats leads the offspring to a thin-outside-fat-inside phenotype. Int. J. Obes. 41, 1279–1287 (2017).

Kannan, S., Srinivasan, D., Raghupathy, P. B. & Bhaskaran, R. S. Association between duration of obesity and severity of ovarian dysfunction in rat-cafeteria diet approach. J. Nutr. Biochem. 71, 132–143 (2019).

Pedro, P. F., Tsakmaki, A. & Bewick, G. A. The glucose tolerance test in mice. in 207–216 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-0385-7_14.

Cook, J. B. et al. Junk food diet-induced obesity increases D2 receptor autoinhibition in the ventral tegmental area and reduces ethanol drinking. PLoS One. 12, e0183685 (2017).

Kannan, S. & Bhaskaran, R. S. Sustained obesity reduces litter size by decreasing proteins regulating folliculogenesis and ovulation in rats - A cafeteria diet model. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 519, 475–480 (2019).

Bazzano, M. V., Paz, D. A. & Elia, E. M. Obesity alters the ovarian glucidic homeostasis disrupting the reproductive outcome of female rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 42, 194–202 (2017).

Ehrenberg, H. M., Mercer, B. M. & Catalano, P. M. The influence of obesity and diabetes on the prevalence of macrosomia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 191, 964–968 (2004).

Lashen, H. Obesity is associated with increased risk of first trimester and recurrent miscarriage: matched case-control study. Hum. Reprod. 19, 1644–1646 (2004).

Luo, H. Q. et al. Effect of prepregnancy obesity on litter size in primiparous minipigs. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 57, 115–123 (2018).

Jones, H. N. et al. High-fat diet before and during pregnancy causes marked up‐regulation of placental nutrient transport and fetal overgrowth in C57/BL6 mice. FASEB J. 23, 271–278 (2009).

George, G. et al. The impact of exposure to cafeteria diet during pregnancy or lactation on offspring growth and adiposity before weaning. Sci. Rep. 9, 14173 (2019).

Gupta, A., Srinivasan, M., Thamadilok, S. & Patel, M. S. Hypothalamic alterations in fetuses of high fat diet-fed obese female rats. J. Endocrinol. 200, 293–300 (2009).

Pereda, J., Bove, I. & Pineyro, M. M. Excessive maternal weight and diabetes are risk factors for macrosomia: A Cross-Sectional study of 42,663 pregnancies in Uruguay. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 11, (2020).

Gaudet, L., Ferraro, Z. M., Wen, S. W. & Walker, M. Maternal Obesity and Occurrence of Fetal Macrosomia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed. Res. Int. 1–22 (2014).

Lin, J., Gu, W. & Huang, H. Effects of paternal obesity on fetal development and pregnancy complications: A prospective clinical cohort study. Front Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 13, (2022).

Bodnar, L. M. et al. Maternal prepregnancy obesity and cause-specific stillbirth. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 102, 858–864 (2015).

Akselsson, A., Rossen, J., Storck-Lindholm, E. & Rådestad, I. Prolonged pregnancy and stillbirth among women with overweight or obesity – a population-based study in Sweden including 64,632 women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 23, 21 (2023).

Åmark, H. et al. Maternal obesity and stillbirth at term; placental pathology—A case control study. PLoS One. 16, e0250983 (2021).

Jazwiec, P. A. et al. Paternal obesity induces placental hypoxia and sex-specific impairments in placental vascularization and offspring metabolism. Biol. Reprod. 107, 574–589 (2022).

Pretz, D., Le Foll, C., Rizwan, M. Z., Lutz, T. A. & Tups, A. Hyperleptinemia as a contributing factor for the impairment of glucose intolerance in obesity. FASEB J. 35, (2021).

Martínez-Montoro, J. I. et al. Adiposity is associated with decreased serum 17-Hydroxyprogesterone levels in Non-Diabetic obese men aged 18–49: A Cross-Sectional study. J. Clin. Med. 9, 3873 (2020).

Blanchette, S., Marceau, P., Biron, S., Brochu, G. & Tchernof, A. Circulating progesterone and obesity in men. Horm. Metab. Res. 38, 330–335 (2006).

Isidori, A. M. et al. Leptin and androgens in male obesity: evidence for leptin contribution to reduced androgen levels**. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 84, 3673–3680 (1999).

Caprio, M. et al. Expression of functional leptin receptors in rodent Leydig Cells1. Endocrinology 140, 4939–4947 (1999).

Genchi, V. A. et al. Adipose tissue dysfunction and Obesity-Related male hypogonadism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 8194 (2022).

Khodamoradi, K. et al. Author correction: the role of leptin and low testosterone in obesity. Int. J. Impot. Res. 35, 499–499 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Sex differences in the effect of testosterone on adipose tissue insulin resistance from overweight to obese adults. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 106, 2252–2263 (2021).

Navarro, G., Allard, C., Xu, W. & Mauvais-Jarvis, F. The role of androgens in metabolism, obesity, and diabetes in males and females. Obesity 23, 713–719 (2015).

Ross, L. A. et al. Profound reduction of ovarian Estrogen by aromatase Inhibition in obese women. Obesity 22, 1464–1469 (2014).

Bazzano, M. V., Torelli, C., Pustovrh, M. C., Paz, D. A. & Elia, E. M. Obesity induced by cafeteria diet disrupts fertility in the rat by affecting multiple ovarian targets. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 31, 655–667 (2015).

Rochester, D. et al. Partial recovery of luteal function after bariatric surgery in obese women. Fertil. Steril. 92, 1410–1415 (2009).

Ribeiro, J., Santos, P., Duarte, J. & Mota, J. Association between overweight and early sexual maturation in Portuguese boys and girls. Ann. Hum. Biol. 33, 55–63 (2006).

Busch, A. S., Højgaard, B., Hagen, C. P. & Teilmann, G. Obesity is associated with earlier pubertal onset in boys. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105, e1667–e1672 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Serum hormone analysis carried out at ‘Prime Gen laboratories, Chennai, India’ is greatly acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RH and BRS designed and conceived the study. RH conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. SD assisted in animal maintenance and experiments. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raghavendhira, H., Srinivasan, D. & Bhaskaran, R.S. Intergenerational effects of cafeteria diet-induced obesity on metabolic and reproductive outcome in rats. Sci Rep 15, 18490 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03019-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03019-2