Abstract

Astrovirus (AstV) is an RNA virus that causes gastroenteritis in humans and various mammal species, including dogs and cats. In this study, we conducted a survey of canine and feline astroviruses in domestic dogs and cats in Bangkok and its vicinity in Thailand. From January 2022 to December 2023, we collected a total of 1,498 rectal swab samples from domestic dogs (n = 862) and cats (n = 636) at private small animal hospitals in Bangkok, Nonthaburi, and Samut Prakran, Thailand. The positive rate for canine astrovirus (CaAstV) was 4.2% (36/862), while that of feline astrovirus (FeAstV) in cats was 10.8% (69/636). We performed complete genome sequencing of Thai-CaAstVs (n = 11) and Thai-FeAstVs (n = 12). Phylogenetic analysis revealed that Thai-CaAstVs were clustered into lineages 1, 3, and 4, while Thai-FeAstVs were grouped within FeAstV group 1. This study identifies novel CaAstV lineages in domestic dogs and represents the first molecular detection of FeAstV in cats in Thailand. Our findings provide detailed information on the genetic characteristics of CaAstVs and FeAstVs currently circulating in Thailand, highlighting challenges for potential diagnostics and future control strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Astrovirus (AstV) is a non-enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus that causes gastroenteritis in both humans and animals worldwide1,2,3. Astrovirus (AstV) was officially classified by the International Committee for Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) in 1995. It belongs to the Astrovirus genus of the family Astroviridae. This classification has been modified several times since then. In 2004, two genera were established: Mamastrovirus (MAstV) and Avastrovirus (AAstV), which infect mammalian and avian species, respectively4. Currently, there are 19 species within the Mamastrovirus genus (MAstV1-19) and 3 species within Avastrovirus (AAstV1-3). Additionally, numerous strains are awaiting classification, some of which are considered tentative new species5,6. The genome size of AstV ranges from about 6.4 to 7.9 kb and consists of three open reading frames (ORFs). These are ORF1a, encoding a non-structural polyprotein; ORF1b, encoding the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase; and ORF2, encoding the viral capsid protein7. The capsid protein plays a crucial role in virus infection. It contains three distinct domains: an N-terminal domain, a hypervariable domain, and a C-terminal domain8. The N-terminal domain is highly conserved, while the other domains show high variability7,9. The hypervariable region is vital for virus attachment to target cells and viral neutralization10.

Canine astrovirus (CaAstV), known as Mamastrovirus 5 (MAstV-5), was first identified in dogs in the 1980s11. CaAstV is an enteric pathogen in dogs and can be found in both healthy and diarrhea dogs. It is widespread in canine populations worldwide12. The first complete genome sequences of CaAstV were reported from the United Kingdom (UK) in 2015 13, followed by complete genome sequences of CaAstV in Hungary and Australia14,15. Some previous studies reported of CaAstV with high genetic diversity12,16,17. Due to its high genetic diversity and recombination in nature of the viruses, it makes CaAstV a potential zoonotic pathogen. For instance, a human astrovirus, genetically similar to CaAstV, was discovered in children with severe diarrhea in Nigeria, suggesting the potential for zoonotic transmission18,19.

Feline Astrovirus (FeAstV), also known as Mamastrovirus 2 (MAstV-2), was first identified in cats with diarrhea in 1981 20. FeAstV can be found in both diarrheic and non-diarrheic cats21. Recently, FeAstV was classified into two different genotypes. FeAstV group 1 includes the representative strain, Bristol, which was detected in the UK in 1998, while FeAstV group 2 contains the representative strain, 1637 F, which was identified in Hong Kong in 2013 22. A previous study reported antibodies against FeAstV in human serum in Australia24. Another study reported genetic similarities between FeAstV and other mammalian astroviruses, such as human AstV and tiger AstV25. A novel FeAstV from an asymptomatic cat in Hong Kong had genetic similarities to human AstV genotype 6 26. Another study also reported that the FeAstV strain Viseu from Portugal and FeAstV strain Bristol from the UK were closely related to the human AstV, Mamastrovirus-1 23. These raise a concern about potential cross-species transmission of the virus. Due to limited information about canine and feline astroviruses, this study aimed to detect and determine the genetic characteristics of CaAstV and FeAstV in domestic dogs and cats circulating in Thailand.

Result

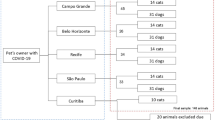

From January 2022 to December 2023, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of canine and feline astrovirus in domestic dogs and cats. Rectal swab samples were collected from domestic dogs (n = 862) and cats (n = 636) from 8 small animal hospitals in Bangkok, Nonthaburi, and Samut Prakran. The samples underwent RT-PCR testing for CaAstV and FeAstV using specific primers for the ORF1b-ORF2 and ORF1a, respectively. In this study, the positive rate was 4.2% (36/862) of CaAstV in dogs and 10.8% (69/636) of FeAstV in cats (Table 1). We analyzed the association between AstV positivity and various parameters, including location, age of animals, sex of animals, clinical status, and season of sample collection. There is a significant association between AstV in dogs and cats and the age of the animals, with younger dogs and cats (up to 6 months old) showing higher positivity (P < 0.05). Additionally, there was high AstV positivity in dogs but not cats during the rainy season, with statistical significance (Supplement Table 3). Meanwhile, the occurrence of FeAstV was significantly associated with the clinical status (P < 0.05), but no significance was observed in CaAstV. On the other hand, there is no significant association between AstV positivity and the locations, breed, and sex. In this study, all AstV-positive samples were also tested for other canine and feline enteric viruses. Our results showed co-infection among AstV and other enteric viruses. For example, we identified CaAstV/CECoV in two samples and CaAstV/CECoV/CRoA in one sample. Additionally, co-infection of FeAstV/FCoV was found in twelve samples (Supplementary Table 4). In this study, we successfully sequenced the whole genome of CaAstV (n = 11) and FeAstV (n = 12). The nucleotide sequences of the whole genome of CaAstV and FeAstV were deposited into the GenBank Database under the accession numbers # PQ 423910-20 and PQ435237-48.

Phylogenetic and genetic analysis of canine astrovirus and feline astrovirus

In this study, we selected 11 CaAstV for whole genome sequencing (Table 2). We successfully sequenced the Thai-CaAstVs and found that the genome size ranged from 6,446 to 6,486, corresponding to its lineages. The complete ORF2 gene sizes of Thai-CaAstVs are 2,475 and 2,496 in lineage 4, 2,505 in lineage 3, and 2,474 in lineage 1. Interestingly, CaAstV of lineages 1 and 3 have not previously been documented in dogs in Thailand. Based on the phylogenetic analysis of the whole genome sequences and complete ORF2 gene, our result showed that all Thai-CaAstVs (n = 11) were grouped with the CaAstVs but in separate clusters from other AstVs found in cats, pigs, sea lions, and humans (Fig. 1). The results of the phylogenetic analysis indicated a genetic diversity of Thai-CaAstVs, with at least 3 lineages circulating in the country. The majority of Thai-CaAstVs (8 out of 11) (CU30305, CU30489, CU30651, CU32040, CU32425, CU33872, CH34591, and CU34596) belonged to lineage 4 of the CaAstV. Among them, seven strains were closely related to Chinese-CaAstV, and one strain was closely related to CaAstV from Hungary. It is noted that this observation suggested that CaAstV of lineage 4 is the predominant lineage circulating in Thailand, similar to the predominant lineage in China. Two Thai-CaAstVs (CU33044 and CU33886) belonged to lineage 3 and were closely related to Australian and UK-CaAstVs, while one Thai-CaAstV (CU29459) clustered with lineage 1 and was closely related to CaAstV from Hungary (Fig. 2).

Phylogenetic analysis of whole genome sequences of Thai-CaAstV and Thai-FeAstV. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA v.7.0 with a neighbor-joining algorithm with a Kimura-2 parameter model with 1,000 replications of bootstrap analysis. Tree visualization was performed by iTol version 6.0 (https://itol.embl.de/). Thai-CaAstVs were indicated as bold text in the blue circle. Thai-FeAstVs were indicated as bold text in the red circle.

For FeAstV, we have successfully sequenced the whole genome of Thai-FeAstVs (n = 12), and the genome size of Thai-FeAstVs was 6,675 bp (Table 2). It is noted that FeAstV has never been documented in cats in Thailand. Phylogenetic analysis of the whole genome and complete ORF2 gene showed that all Thai-FeAstVs (n = 12) were grouped with the FeAstVs group 1 but in separate clusters from AstVs in dogs, pigs, sea lions, and humans. In detail, most Thai-FeAstVs (n = 10) were closely related to Chinese-FeAstVs of group 1. Two Thai-FeAstVs (CU28799 and CU34594) were clustered with FeAstVs group 1 from Australia (Figs. 1 and 3).

Pairwise comparison of the complete genome of Thai-CaAstVs (CU34591) revealed high nucleotide and amino acid identities among Thai-CaAstV of lineage 4 (93.3–93.8% nt identities; 93.6–94.2% aa identities). Similarly, the Thai-CaAstV of lineage 4 showed high nucleotide and amino acid identities with reference CaAStVs of lineage 4 from Hungary (Hun/2/2012), China (China/ZJ/19), the UK (UK/Lincoln/12), and Thailand (S76TH2021) (Supplement Table 5). The genetic analysis of the ORF2 gene involved comparing amino acid changes between Thai-CaAstVs and reference CaAstVs from each lineage. Most Thai-CaAstVs of lineage 4 had identical amino acids to those of CaAstVs lineage 4 at the hypervariable region (Table 3 and Supplement Fig. 2). However, one Thai-CaAstV (CU34591) showed a deletion of seven amino acids (PTIEEEQ) at positions 733–739, which was similar to the CaAstVs from the UK (UK/Lincoln/12), Hungary (Hun/2/12), and Thailand (G21TH2021). For Thai-CaAstV of lineage 1 (CU29459), we observed seven amino acid deletions at positions 729–735, identical to the reference CaAstVs (Hun/126/12 and Ita/GLE/10). For Thai-CaAstVs of lineage 3 (CU33044, CU33886), most amino acid determinants were identical to the CaAstV from the UK (UK/Gillingham/12), except for one unique amino acid residue (V/T → I) observed at position 729, which is in an acidic region of the ORF2 gene (Table 3).

Pairwise comparison of the complete genome of Thai-FeAstV (CU28799) showed high nucleotide and amino acid identities among Thai-FeAstVs (90.9–96.3% nt identities; 91.3–96.6% aa identities). CU28799 also exhibited high genetic identities with the reference FeAstV group 1, with 92.1–93.4% nt identities and 92.5–94.9% aa identities. However, Thai-FeAstV (CU28799) showed low nucleotide and amino acid identities compared to FeAstVs of group 2. It is noted that the complete genome of Thai-FeAstV could not be compared with the FeAstV from the UK (Bristol strain) due to its unavailability in the GenBank database (Supplementary Table 6). The genetic analysis of the deduced among acids in ORF2 of Thai-FeAstVs and reference FeAstV groups 1 and 2 revealed significant differences in the hypervariable region. These differences can be used to distinguish between FeAstV groups 1 and 2. For instance, FeAstVs group 1 contained amino acid deletion at positions 450, 471, 472, and 649, while FeAstVs group 2 had amino acid deletions at positions 525, 549, and 594–597 (Table 4 and Supplement Fig. 3).

Discussion

Canine Astrovirus (CaAstV) and Feline Astrovirus (FeAstV) cause gastroenteritis in domestic dogs and cats. The viruses are spread worldwide in the canine and feline populations16. In this study, the positive rate of AstVs was 4.2% (36/862) for CaAstVs in dogs, which was lower compared with other countries such as China, France, Korea, Thailand, and Vietnam, where the prevalence ranged from 20.9 to 42% 12,16,17,27–29. It is important to note that there are some discrepancies due to the different geographical locations and the criteria used for sample collections, including clinical status (diarrhea or non-diarrhea), age group (puppies or adults), and sampling site (shelters or hospitals). For Feline Astrovirus (FeAstV), this study is the first to report the molecular detection of FeAstV in domestic cats in Thailand at a positive rate of 10.8% (69 out of 636 cats). This positivity rate was lower compared to other Asian countries such as China (23.4%), Japan (21.1%), and South Korea (17.7%)21,22,30. However, the prevalence of FeAst in Thailand was comparable to studies in Eastern China (6.1%) and the US (10.0%)31,32. The difference in positivity rate was attributed to varying geographic locations and the age groups of the animals. The findings of this study provided critical data on the prevalence of CaAstV and FeAstV in dog and cat populations in Thailand, particularly in urbanized areas, aiding in the understanding of virus distribution.

There was a significant association between AstVs in dogs and cats and the age of the animals. Younger dogs and cats (up to 6 months old) show higher positivity rates (P < 0.05). This result was in line with several previous studies in China12, France27, Japan30,33, Greece34, and Canada35. By season, it was observed that AstV infection in dogs and cats was most common during the rainy season, especially in dogs (with statistical significance). This could be due to the suitable environment created during the rainy season, which may facilitate the transmission of viruses. The association between the season and virus prevalence will aid in better managing future outbreaks effectively12. The results of this study did not definitively conclude the association between AstV and clinical signs in animals. The positivity rates of CaAstV and FeAstV were higher in symptomatic animals (statistical significance in FeAstV). Similarly, the previous studies conducted in various countries, such as China, Hungary, and Italy, reported a high prevalence of CaAstV in symptomatic dogs12,16,36,37. Additionally, cats with gastroenteritis had shown a higher detection rate of FeAstV than asymptomatic cases22,32.

The phylogenetic analysis of the whole genome and complete ORF2 gene revealed a high genetic diversity of Thai-CaAstVs. At least three lineages (lineages 1, 3, and 4) were identified. Most Thai-CaAstVs were closely related to CaAstV of lineage 4 from China and Hungary, indicating the predominant presence of lineage 4 in the country. This finding was consistent with a previous study in Thailand29. It is important to note that this study was the first to report the novel CaAstV lineages (lineage 1 and 3) circulating in Thailand. Additionally, the Thai-CaAstV lineage 1 was not only first reported in Thailand but also in other Asian countries, although lineage 1 and 3 have already been reported in European countries, including Hungary36 and Italy37. The phylogenetic analysis of whole genome sequences and complete ORF2 gene showed that all Thai-FeAstVs were grouped with FeAstV group 1. Thai-FeAstV were closely related and clustered with FeAstV from the UK (Bristol) and China (17JL0318, 17HRB0511). It is noted that this study is the first report on the detection and genetic characterization of FeAstVs in Thailand. Our findings supported that the circulation of various CaAstV lineages indicated a high genetic diversity of CaAstV as well as the first report on the detection of FeAstV in Thailand, which will be beneficial for future preventive and control measures for CaAstV and FeAstV infection in the dog and cat populations.

In the genetic analysis of the hypervariable region of the ORF2 gene, Thai-CaAstV of lineage 4 did not contain seven amino acid deletions (PTIEEEQ) (positions 733–739), except one CaAstV (CU34591), similar to the CaAstV from China (China/ZJ/19) and Thailand (S76TH2021)16,29. In contrast, in Thai-CaAstV of lineage 1 (CU29459), seven amino acid deletions at positions 729–735 were observed, identical to the reference CaAstVs (Hun/126/12 and Ita/GLE/10). In comparison, in Thai-CaAstVs of lineage 3 (CU33044, CU33886), one unique amino acid residue (V/T → I) was observed at position 729. This observation revealed distinct amino acid patterns in each CaAstV lineage and aligned with a previous study in Thailand and Vietnam29. For Thai-FeAstV, our result revealed significant differences in the hypervariable region between FeAstV groups 1 and 2. FeAstVs group 1 contained amino acid deletion at positions 450, 471, 472, and 649, while FeAstVs group 2 had amino acid deletions at positions 525, 549, and 594–597. Our results indicated that some amino acid insertions and deletions can be used to distinguish FeAstV group 1 and group 2. This result was consistent with the previous study in China, which indicated the classification of the FeAstV group based on the ORF2 hypervariable region31. It also noted that the variable C-terminal of the capsid protein is mainly associated with the virus antigenicity38,39.

In this study, only FeAstVs group 1 was found to have identical amino acids and are closely related to HAstV (Mamastrovirus 1; HAstV 1). Thus, as previously reported, the zoonotic potential from interspecies transmission should not be ignored23. Notably, the properties of capsid proteins of AstV from dogs and cats were similar to those of HAstV, in which mutations in capsid protein and structure of the viruses can also lead to changes in the virus’s ability to bind, enter, and uncoated in host cells10,40. The speculation regarding potential zoonotic transmission emphasizes the importance of monitoring the virus to prevent possible cross-species infections41 Our findings further highlight the need for routine surveillance for CaAstV and FeAstV, which will be important for human and animal health.

In conclusion, our study enhanced our understanding of Astrovirus infection in domestic dogs and cats in Thailand. Our findings revealed a significant prevalence of CaAstV and FeAstV and its association with the age of the animals and season. Phylogenetic and genetic analysis showed a high genetic diversity of CaAstV, including the identification of novel CaAstV lineages 1 and 3. The study also marked the first report on the detection and genetic characterization of FeAstV. It is essential to conduct routine surveillance and monitoring to comprehend the molecular epidemiology and genetic variations of CaAstV and FeAstV in Thailand. This information will be valuable for potential diagnostics and future prevention and control strategies.

Materials and methods

Samples collection

From January 2022 to December 2023, we conducted a cross-sectional sample collection from 8 animal hospitals in Bangkok, Nonthaburi, and Samut Prakan. In total 1,498 rectal swab samples were collected from 862 dogs and 636 cats with asymptomatic and symptomatic conditions, including vomiting and diarrhea. The samples were taken from dogs of all ages, sex, breed, and clinical signs and the animal demographic data were recorded. This study was conducted under the Chulalongkorn University Animal Care and Uses Protocol (CU-VET IACUC#2331098) guidelines and regulations.

Detection of canine and feline astrovirus

The RNA extraction was conducted using the GeneAll® GENTiTM Viral DNA/RNA Extraction Kit (GeneAll®; Lisbon, Portugal) on a GENTiTM 32 (GeneAll®; Lisbon, Portugal), following the manufacturer’s instructions. For CaAstV detection, we used nested RT-PCR with specific primers targeting the ORF1b-ORF2 region. The nested RT-PCR was performed using SuperScript™ III RT-PCR with Platinum™ Taq Mix (Invitrogen, Thermofisher, USA). The specific primers for the ORF1b-ORF2 region are as follows: the forward primer dAV2(F) TGGAATGTGGGTYAAGCC and the reverse primers, dAV3(R1) GAGTTGGAAGCTGTTGATTCT and dAV4 (R2) GCAAGTTCCAGCTCTACTGC18,23. In brief, a nested RT-PCR was conducted in a 50 µl final volume. This consisted of 3 µl of template RNA, 1X Reaction Mix, 0.24 µM of each forward and reverse primer, 400 units of SuperScript III RT (Invitrogen, Thermofisher, USA), and distilled water to get a final volume of 50 µl. The nested RT-PCR was performed under the following conditions: The first round of PCR with the primers dAV2 and dAV3 involves 55 °C for 15 min, 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 68 °C for 1 min, and a final extension for at 68 °C for 5 min. For the second round of PCR, the primers dAV2 and dAV4 were used. The PCR conditions consist of the following steps: an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 15 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were then run on a 1.5% agarose gel containing RedSafeTM (iNtRON Biotechnology, Inc., Korea) at 100 volts for 45 min. The expected PCR product of the CaAstV was 660 bp (Supplement Fig. 1).

For FeAstV, one-step RT-PCR was conducted using SuperScript™ III RT-PCR with Platinum™ Taq Mix (Invitrogen, Thermofisher, USA). The specific primers targeting the ORF1a gene were the forward primer FeAstV (AF) GAAATGGACTGGACACGTTATGA and the reverse primer FeAstV (BF) GGCTTGACCCACATGCCGAA. Briefly, a one-step RT-PCR was performed using a 50 µl final volume, including 3 µl of template RNA, 1X Reaction Mix, 0.24 µM of each forward and reverse primer, 400 units of SuperScript III RT (Invitrogen, Thermofisher, USA), and distilled water to get a final volume of 50 µl. The RT-PCR assay involved steps: an initial step at 55 °C for 30 min, an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and extension at 68 °C for 1 min, and final extension step at 68 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were then run on a 1.5% agarose gel mixed with RedSafeTM (iNtRON Biotechnology, Inc., Korea) at 100 volts for 45 min. The expected size of the FeAstV-positive product was 418 bp (Supplement Fig. 1). In addition, all positive samples were examined for co-infection with other enteric viruses in dogs and cats, such as canine coronaviruses (CECoV), feline coronavirus (FCoV), Canine Rota A virus (CaRoV), and Feline Rota A virus (FeRoA).

Genetic characterization of canine and feline astrovirus

In this study, we conducted whole genome sequencing of CaAstV (n = 11) and FeAstV (n = 12) for genetic characterization. The representative CaAstV and FeAstV samples were selected based on epidemiological and demographic data, including age, collection date, and clinical history. Whole genome sequencing was conducted by amplification of each ORF using newly designed primers by the primer 3 plus program and primer sets previously described31,42 (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The PCR amplification of ORFs was carried out in a final total volume of 50 µl. The mixture consisted of 3 µl of template RNA, 1X Reaction Mix, 0.24 µM of each forward and reverse primer, 400 units of SuperScript III RT (Invitrogen, CA), and distilled water. The PCR condition included an initial step at 55 °C for 30 min, an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 45 °C for 30 s, and extension at 68 °C for 1 min, as well as a final extension step at 68 °C for 5 min. PCR products were purified using NucleoSpin® Gel and PCR Clean-up (MACHEREY-NAGELTM, Germany) and then subjected to Sanger Sequencing at Bionic Company, Korea. The nucleotide sequences were edited, validated, and assembled using SeqMan software v.5.03 (DNASTAR Inc.; Wisconsin, USA).

Phylogenetic and genetic analysis of CaAstV and FeAstV

Phylogenetic analysis of CaAstV and FeAstV was conducted by comparing the nucleotide sequences of CaAstV reference strains in each lineage and FeAstV reference strains in each group, as well as other reference strains of the Astroviruses available from the GenBank database, including humans (MAstV 1 & 6), pigs (MAstV 3) and Sea lions (MAstV 4). Phylogenetic trees of whole genome sequences and ORF2 gene of CaAstV and FeAstV were constructed using MEGA v.11.0 (Tempe, AZ, USA) with the neighbor-joining method applying the Kimura 2-parameter and 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Nucleotide and amino acid similarities of Thai-CaAstV and FeAstV were performed by comparing Thai-CaAstV and FeAstV with each CaAstV and FeAstV reference lineage from the GenBank database. For genetic analysis, deduced amino acids of ORF2 of Thai-CaAstV and FeAstV were aligned with those of CaAstV reference lineages and FeAstV reference groups using MegAlign software v.5.03 (DNASTAR Inc.; Wisconsin, USA). The hypervariable region related to receptor binding of the viruses and host preferences were evaluated.

Statistical analysis

The association between the prevalence of CaAstV and FeAstV in domestic dogs and cats and the demographic data, including the age of animals, date of collection, clinical history, and locations, were analyzed using the chi-square test (SPSS Statistics, version 29.0.1.0). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The nucleotide sequence data are available in the GenBank database under accession numbers # PQ 423910-20 and PQ435237-48.

References

Donato, C. & Vijaykrishna, D. The broad host range and genetic diversity of mammalian and avian astroviruses. Viruses 9, 102 (2017).

Mischenko, V. А., Mischenko, A. V. & Nikeshina, T. B. & Petrova, O. N. Astrovirus infection in animals. VETERINARY Sci. TODAY, 322 (2024).

Vu, D. L., Bosch, A., Pintó, R. M. & Guix, S. Epidemiology of classic and novel human astrovirus: gastroenteritis and beyond. Viruses 9, 33 (2017).

Krishnan, T. Novel human astroviruses: challenges for developing countries. Virusdisease 25, 208–214 (2014).

Woo, P. C. et al. A novel astrovirus from dromedaries in the middle East. J. Gen. Virol. 96, 2697–2707 (2015).

Karlsson, E. A. et al. Non-human primates harbor diverse mammalian and avian astroviruses including those associated with human infections. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005225 (2015).

Arias, C. F. & DuBois, R. M. The astrovirus capsid: a review. Viruses 9, 15 (2017).

Dong, J., Dong, L., Méndez, E. & Tao, Y. Crystal structure of the human astrovirus capsid Spike. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 108, 12681–12686 (2011).

Mendez, E. & Astroviruses Fields Virol. 981–1000 (2007).

Krishna, N. K. Identification of structural domains involved in astrovirus capsid biology. Viral Immunol. 18, 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1089/vim.2005.18.17 (2005).

Williams, F. P. Astrovirus-like, coronavirus-like, and parvovirus-like particles detected in the diarrheal stools of beagle pups. Arch. Virol. 66, 215–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01314735 (1980).

Zhou, H. et al. Detection and genetic characterization of canine astroviruses in pet dogs in Guangxi, China. Virol. J. 14, 1–6 (2017).

Caddy, S. L. & Goodfellow, I. Complete genome sequence of canine astrovirus with molecular and epidemiological characterisation of UK strains. Vet. Microbiol. 177, 206–213 (2015).

Mihalov-Kovács, E. et al. Genome analysis of canine astroviruses reveals genetic heterogeneity and suggests possible inter-species transmission. Virus Res. 232, 162–170 (2017).

Moreno, P. S. et al. Characterisation of the canine faecal Virome in healthy dogs and dogs with acute diarrhoea using shotgun metagenomics. PloS One. 12, e0178433 (2017).

Zhang, W. et al. Epidemiology, genetic diversity and evolution of canine astrovirus. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 67, 2901–2910. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.13663 (2020).

Choi, S. et al. Phylogenetic analysis of astrovirus and kobuvirus in Korean dogs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 76, 1141–1145 (2014).

Japhet, M. O. et al. Viral gastroenteritis among children of 0–5 years in Nigeria: characterization of the first Nigerian Aichivirus, Recombinant Noroviruses and detection of a zoonotic astrovirus. J. Clin. Virol. 111:, 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2018.12.004 (2019).

De Benedictis, P., Schultz-Cherry, S., Burnham, A. & Cattoli, G. Astrovirus infections in humans and animals - molecular biology, genetic diversity, and interspecies transmissions. Infect. Genet. Evol. 11, 1529–1544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2011.07.024 (2011).

Hoshino, Y., Zimmer, J., Moise, N. & Scott, F. Detection of astroviruses in feces of a Cat with diarrhea. Arch. Virol. 70, 373–376 (1981).

Cho, Y. Y. et al. Molecular characterisation and phylogenetic analysis of feline astrovirus in Korean cats. J. Feline. Med. Surg. 16, 679–683 (2014).

Yi, S. et al. Molecular characterization of feline astrovirus in domestic cats from Northeast China. PLoS One. 13, e0205441 (2018).

Ng, T. F. F. et al. Feline fecal Virome reveals novel and prevalent enteric viruses. Vet. Microbiol. 171, 102–111 (2014).

Marshall, J. A. et al. Virus and virus-like particles in the faeces of cats with and without diarrhoea. Aust Vet. J. 64, 100–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-0813.1987.tb09638.x (1987).

Zhang, H. H. et al. Genomic characterization of a novel astrovirus identified in Amur Tigers from a zoo in China. Arch. Virol. 164, 3151–3155 (2019).

Lau, S. K. et al. Complete genome sequence of a novel feline astrovirus from a domestic Cat in Hong Kong. Genome Announc. 1, 708–713 (2013).

Grellet, A. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of astrovirus infection in puppies from French breeding kennels. Vet. Microbiol. 157, 214–219 (2012).

Castro, T. et al. Molecular characterisation of calicivirus and astrovirus in puppies with enteritis. (2013).

Nguyen, T. V., Piewbang, C. & Techangamsuwan, S. Genetic characterization of canine astrovirus in non-diarrhea dogs and diarrhea dogs in Vietnam and Thailand reveals the presence of a unique lineage. Front. Vet. Sci. 10, 1278417. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2023.1278417 (2023).

Soma, T., Ogata, M., Ohta, K., Yamashita, R. & Sasai, K. Prevalence of astrovirus and parvovirus in Japanese domestic cats. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 82, 1243–1246. https://doi.org/10.1292/jvms.20-0205 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Genetic characterization and phylogenetic analysis of feline astrovirus from Anhui Province in Eastern China. 3 Biotech. 10, 1–10 (2020).

Sabshin, S. J. et al. Enteropathogens identified in cats entering a Florida animal shelter with normal feces or diarrhea. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 241, 331–337. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.241.3.331 (2012).

Takano, T., Takashina, M., Doki, T. & Hohdatsu, T. Detection of canine astrovirus in dogs with diarrhea in Japan. Arch. Virol. 160, 1549–1553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-015-2405-3 (2015).

Stamelou, E. et al. First report of canine astrovirus and Sapovirus in Greece, hosting both asymptomatic and gastroenteritis symptomatic dogs. Virol. J. 19, 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-022-01787-1 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Astrovirus outbreak in an animal shelter associated with feline vomiting. Front. Vet. Sci. 8, 628082. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.628082 (2021).

Mihalov-Kovács, E. et al. Genome analysis of canine astroviruses reveals genetic heterogeneity and suggests possible inter-species transmission. Virus Res. 232, 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2016.12.005 (2017).

Martella, V. et al. Enteric disease in dogs naturally infected by a novel canine astrovirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 1066–1069 (2012).

Bass, D. M. & Qiu, S. Proteolytic processing of the astrovirus capsid. J. Virol. 74, 1810–1814. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.74.4.1810-1814.2000 (2000).

Geigenmuller, U., Ginzton, N. H. & Matsui, S. M. Studies on intracellular processing of the capsid protein of human astrovirus serotype 1 in infected cells. J. Gen. Virol. 83, 1691–1695. https://doi.org/10.1099/0022-1317-83-7-1691 (2002).

Ykema, M. & Tao, Y. J. Structural insights into the human astrovirus capsid. Viruses 13 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/v13050821

Martella, V. et al. Detection and characterization of canine astroviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 92, 1880–1887 (2011).

Li, M. et al. Prevalence and genome characteristics of canine astrovirus in Southwest China. J. Gen. Virol. 99, 880–889. https://doi.org/10.1099/jgv.0.001077 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank Chulalongkorn University’s Graduate Scholarship Programme for ASEAN or Non-ASEAN Countries for supporting the first author of the Ph.D. scholarship (YNT). Chulalongkorn University financially supports the Center of Excellence for Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases in Animals (CUEIDAs). The Thailand Science Research and Innovation Fund Chulalongkorn University, FF68; HEAF68310011 supported this research. This project was also partially funded by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT Senior Scholar 2022 #N42A650553) and the Faculty of Veterinary Science, Chulalongkorn University (Veterinary Science Research Fund, #RI 1/2566).

Funding

Chulalongkorn University supported the first author’s Ph.D. scholarship, “the Graduate Scholarship Programme for ASEAN or Non-ASEAN Countries”. Chulalongkorn University financially supports the Center of Excellence for Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases in Animals (CUEIDAs). The Thailand Science Research and Innovation Fund Chulalongkorn University, FF68: HEAF68310011 supported this research. This project was partially funded by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT Senior Scholar 2022 #N42A650553) and the Faculty of Veterinary Science, Chulalongkorn University (Veterinary Science Research Fund, #RI 1/2566).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YNT drafted the manuscript. YNT, EMP, and HWP performed sample collection. YNT, KC, CN, EC, WJ, and SC performed virus detection, whole genome characterization, and phylogenetic analysis. YNT, KC, CN, and SC participated in phylogenetic and genetic analysis. AA designed the study, performed data analysis, drafted, revised, and approved the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted under the approval of the Institute for Animal Care and Use Protocol of the CU-VET, Chulalongkorn University (IACUC #2331076). Verbal informed consent was obtained from all pet owners for sample collection in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thaw, Y.N., Charoenkul, K., Nasamran, C. et al. Monitoring and characterization of canine and feline astroviruses in domestic dogs and cats in Thailand. Sci Rep 15, 18293 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03037-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03037-0