Abstract

Healthcare professionals play a vital role in managing and containing disease outbreaks. This study evaluated the level of readiness, knowledge, and attitudes of healthcare professionals in Jordan towards Monkeypox (Mpox) disease and explored factors associated with poor level of readiness, poor level of knowledge, and negative attitude toward Mpox. A pre-validated cross-sectional survey was carried out on healthcare professionals (physicians, pharmacists and nurses) actively involved in patient care in Jordan from 15 July to 30 September 2024. After being pilot-tested on 30 healthcare professionals, the 48-item questionnaire, collected information on participant’s demographics, and readiness, knowledge, and attitudes towards Mpox. Multivariable logistic regression identified factors associated with poor readiness, poor knowledge, and negative attitude. A total of 1093 healthcare professionals participated in the survey, including 329 physicians (30.1%), 346 pharmacists (31.7%), and 418 nurses (38.2%). Among participants, 58.0% demonstrated high levels of readiness, and 53.9% showed high levels of knowledge regarding Mpox. However, one-third (33.6%) were unaware of the availability of an effective vaccine, and only 30.7% recognized the lack of an effective treatment for Mpox. Nurses had higher readiness scores (median: 5, IQR: 5) compared to physicians (median: 4, IQR: 6) and pharmacists (median: 4, IQR: 6), while physicians scored highest in knowledge (median: 8, IQR: 4), followed by nurses (median: 7, IQR: 4) and pharmacists (median: 5, IQR: 4). No prior pandemic response experience was positively associated with increased likelihood of poor Mpox readiness (AOR: 2.11, 95% CI: 1.60–2.78) and poor knowledge (AOR: 1.40, 95% CI: 1.08–1.81). Poor knowledge was also linked to relying on workshops as the main information source (AOR: 2.55, 95% CI: 1.50–4.32). Negative attitudes were associated with lack of prior response experience (AOR: 1.36, 95% CI: 1.04–1.77), not using digital health records (AOR: 1.56, 95% CI: 1.18–2.05), and depending on colleagues for information (AOR: 1.73, 95% CI: 1.00–3.00) while attending workshop was protective against having negative attitude (AOR: 0.32, 95% CI: 0.17–0.60). While over half of healthcare professionals in Jordan demonstrated high readiness and knowledge regarding Mpox, significant gaps remain, particularly in vaccine and treatment awareness. Nurses showed higher readiness, whereas physicians had better knowledge levels. Targeted training and improved information dissemination strategies are needed to enhance Mpox response capacity among healthcare professionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Monkeypox (Mpox) is a viral disease caused by a double-stranded DNA virus. The virus is primarily transmitted via close contact with an infected individual or animal, or through exposure to materials contaminated with the virus1. Mpox is categorized into two main types: clade I and clade II. Human-to-human transmission of Mpox clade IIb primarily occurs through direct physical contact with the skin, saliva, or mucous membranes of an infected individual2. Additionally, sexual and intimate contacts have been identified as major transmission routes. The incubation period of Mpox can range from 3 to 17 days and symptoms can last 2 to 4 weeks2.

On July 23, 2022, The World Health Organization (WHO) declared Mpox a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC)3. As of 03 November 2024, there have been 109,699 confirmed Mpox cases and 236 deaths reported worldwide across 123 countries4. In Africa, the outbreak is trending upward, mostly due to surges in Uganda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. With 8662 confirmed cases and 43 confirmed fatalities, the Democratic Republic of the Congo continues to be the most impacted nation4. These emerging global trends underscore the critical need for all countries to maintain vigilance and readiness. Although Jordan has reported fewer Mpox cases compared to highly affected regions5, it has not remained entirely unaffected by the outbreak.

During public health emergencies, such as the recent COVID-19 pandemic and Mpox outbreaks, it is imperative for all nations to implement immediate and comprehensive response plans to ensure timely and effective disease prevention and control. Healthcare professionals play a critical role in public health emergency response plans, bearing significant responsibility for disease control and outbreak management6. Their readiness, including practical and technical readiness, is crucial for effective response. An integral component of an effective public health strategy is ensuring that healthcare professionals possess comprehensive knowledge about the disease, its transmission, and prevention strategies, as well as maintaining positive attitudes towards outbreak management7. An effective public health response relies not only on robust disease surveillance systems, the sufficient availability and proper use of personal protective equipment, and the provision of pharmaceutical preventive measures, such as vaccines, but also on the readiness and proactive attitudes of healthcare professionals. Their level of knowledge and attitude directly influence their ability to manage cases and control the spread of the disease8. Existing literature predominantly focuses on assessing healthcare professionals’ common knowledge and attitudes towards Mpox9,10, without addressing their practical and technical readiness to handle the outbreak. A study from Saudi Arabia evaluated doctors’ readiness regarding Mpox and found that almost two-thirds of the participants were not confident that they could diagnose or manage the monkeypox11. In Ethiopia, less than half of healthcare professionals surveyed (28.1%) demonstrated good knowledge and favorable attitudes toward the Mpox12. In the United Arab Emirates, Iraq, and Egypt, a quarter of the students sampled had poor knowledge of Mpox and more than half (57.2%) reported moderate anxiety13.In Kurdistan Region of Iraq, the mean knowledge and attitude towards Mpox among healthcare workers were 8.2 (standard deviation: 3.2) out of 16 and 3.4 (SD: 1.4) out of 5, respectively14. A Lebanese study found that one-third of the healthcare professionals surveyed demonstrated high-level of knowledge related toMpox, scoring above the 75th percentile (n = 218, 33.7%). Additionally, fewer than one-third showed positive attitudes towards Mpox, with scores exceeding the 75th percentile (n = 198, 30.7%)15. However, the conflicting results in previous studies and small sample size necessitate further research, which is needed to comprehensively evaluate the practical and technical readiness of healthcare professionals across different settings to effectively respond to Mpox outbreaks.

In Jordan, poor awareness among medical professionals has been documented in two studies. Nonetheless, information about their level of readiness to deal with Mpox is lacking15,16. The first confirmed Mpox case was documented on September 8, 2022, involving a citizen who had returned from Europe. The second case was spotted on September 2, 2024, in a 33-year-old non-Jordanian resident5. In response, a national Mpox preparation and response strategy has been released by the Jordanian Ministry of Health in cooperation with the National Centre for Security and Crisis Management5. Increased monitoring at entrance points, timely diagnostic testing, isolation of confirmed cases, and incorporation of Mpox surveillance into the Jordan Integrated Electronic Reporting System (JIERS) are all part of this approach5. Despite these efforts, there remains a significant gap in understanding the readiness of healthcare professionals to effectively respond to Mpox outbreaks. To address this gap, this study comprehensively evaluates the level of readiness, knowledge, and attitudes of healthcare professionals in Jordan toward Mpox and identifies factors associated poor level of readiness, poor level of knowledge, and negative attitudes towards Mpox, providing valuable insights to inform future public health strategies.

Materials and methods

Study design, participants, and sampling

A cross-sectional survey was carried out among healthcare professionals in Jordan from July 15, 2024, to September 30, 2024. Physicians, pharmacists and nurses with active jobs in Jordan’s public and private sectors and directly involved in patient care irrespective of their gender and length of professional service were eligible to be included in the study. Healthcare professionals were deemed ineligible to participate in the survey if they were not employed in healthcare settings or held medical-related degrees but were working outside the medical field, such as in medical sales or as representatives.

In this study, a combination of convenience and snowball sampling methods were adopted. The convenience sampling technique was used to recruit the main participants from readily available healthcare institutions in major urban centers, including clinics and hospitals. The key respondents consisted of healthcare professionals who satisfied our inclusion criteria and were easily accessible for participation. Then, snowball sampling was implemented by asking main responders to recommend peers within their professional networks who also satisfied the study’s inclusion criteria. This dual sampling strategy not only expedited data collection but also broadened the representativeness of the sample in accordance with recommendations for enhancing methodological rigor17.

Sample size calculation

The total number of healthcare professionals in Jordan is 92,416 including 36,437 (39.4%) physicians, 32,984 (35.7%) nurses, and 22,995 (24.9%) pharmacists.

To calculate the sample size, we used the following equation8 considering that there is an unknown information regarding the level of readiness, knowledge, and attitude towards Mpox in Jordan.

Where: n = required sample size, Z = Z-value (Z statistics) corresponding to the desired confidence level, P = estimated proportion of the population possessing the attribute of interest, and d = margin of error (desired level of precision).

To account for an anticipated 50% response rate, a target sample size of 770 healthcare professionals was determined. This included a minimum of 303 physicians (39.4% of the sample), 275 nurses (35.7%), and 192 pharmacists (24.9%) to ensure adequate representation across key professional groups.

Study tools and measures

The data collection tool utilized in this study was adapted from validated questionnaires designed for healthcare professionals18,15,19. A set of questions assessing readiness, knowledge, and attitudes towards Mpox was selected and modified to align with the Jordanian context. The developed questionnaire included 48 questions, divided into four sections. The first section gathers professional and demographic data including age, sex, occupation, work setting and location of the workplace, medical experience, involvement in prior epidemics, use of digital health records, and primary source of information regarding Mpox. The second section included ten (yes or no) items to collect information on the preparedness to deal with Mpox, with regard to resource availability and the capacity-building of healthcare professionals. The third section included 14 (yes or no) items to collect data about the level of knowledge towards Mpox. The Mpox-specific knowledge items collected information on the signs, symptoms, therapies, and features of infection with Mpox as well as its modes of transmission. The fourth section inquired about the attitudes of study participants towards Mpox infection. This section included six Likert scale items. The potential item-specific response ranged from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. These items, for example, inquired about adequacy and effectiveness of the existing infection control protocols in managing Mpox, need for more training and resources, and willingness to receive smallpox vaccine to prevent Mpox. Based on methodological considerations to support binary analysis, responses marked as “Neutral” were grouped with “Disagree” and “Strongly Disagree.” Neutral responses often indicate indecision, lack of strong opinion, or passive disagreement rather than true neutrality. Grouping them with disagreement categories allows for a more conservative and rigorous classification of positive attitudes.

Following data collection and cleaning, a binary scoring system was applied. A score of ‘1’ was assigned to indicate the presence of readiness, and ‘0’ to indicate its absence. For the knowledge section, correct responses were scored as ‘1’, while incorrect responses were assigned a score of ‘0’. In the attitudes section, a positive attitude was coded as ‘1’, and a negative attitude as ‘0’. The total score for each category was calculated, with maximum possible scores of ten for readiness, 14 for knowledge, and six for attitudes. Participants who achieved scores less than the median score in each category were classified as demonstrating poor readiness, poor knowledge, or a negative attitude. These were the three outcome categories of interest.

Pilot test and content validity

To ensure relevance, readability and understandability, and content validity of the three scales seeking information about readiness, knowledge, and attitudes towards Mpox, 30 healthcare professionals (ten physicians, ten pharmacists, and ten nurses) were asked to review and complete the questionnaire. The surveyed healthcare professionals indicated that the questionnaire was clear, comprehensible, and effectively captured the necessary information to address the study objectives. Additionally, feedback from the pilot test highlighted minor suggestions for improving clarity, which were incorporated to enhance readability and ensure precise interpretation of the questions.

To align the study questionnaire with the Jordanian context, minor modifications were made without altering its core items. During the pilot test, participants requested more clarity on Mpox-related training and exercises, specifically whether “training” included formal workshops, on-the-job sessions, or peer-led discussions, and if “simulation exercises” referred to comprehensive outbreak drills or smaller-scale scenario-based practices. To address these requests, we added brief explanations and examples within the questionnaire (e.g., “Have you participated in any formal or informal training sessions on Monkeypox identification?” and “Have you taken part in any tabletop or full-scale simulation exercises for infectious disease outbreaks, including Monkeypox?”). Additionally, attitude-related questions that were not relevant to the Jordanian context were removed, and some knowledge-based questions were slightly adjusted. Furthermore, we cross-checked the knowledge items with the latest guidelines and information released by the WHO and US CDC on Mpox to ensure accuracy and relevance. These minor yet necessary modifications are not expected to affect comparability with previous studies. The internal consistency of each scale content assessment among the healthcare professionals was measured using Cronbach’s alpha test. The test yielded a coefficient of 0.78 for knowledge, 0.83 for readiness, and 0.76 for attitude, indicating acceptable reliability.

Data collection procedure

Data collection was conducted using two complementary approaches to ensure a broad and representative sample of healthcare professionals. First, sixty-three senior undergraduate pharmacy students (data collectors) completing their clinical rotations in community pharmacies and hospitals across Jordan were assigned to collect data. The data collection phase took place from July 15, 2024, to September 30, 2024. Before data collection phase commences, data collectors underwent extensive training covering research ethics, data collection techniques, and professional communication techniques for interacting and engaging with healthcare providers. Their ability to appropriately communicate the objectives and methods of the study while upholding professional standards was examined and ensured. The trained students conducted face-to-face surveys by distributing the self-administered questionnaires directly to healthcare professionals in their respective clinical sites.

Second, faculty members of the Department of Pharmacy Practice also provided the department heads of five large hospitals with the survey link. These department heads were requested to disseminate the online self-administered questionnaire among their medical and nursing staff. This strategy made it feasible to reach more eligible participants across departments and shifts and let healthcare workers engage whenever it was most convenient for them.

Statistical analysis

Normality assumption of the continuous variables was explored utilizing the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The non-normally distributed continuous variables were described as medians with their corresponding interquartile range (IQR), while categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. The median score utilized as the threshold to categorize knowledge and readiness levels into two groups: ‘high level’ (≥ median score) and ‘poor level’ (< median score). The Kruskal-Wallis test was employed to identify statistically significant differences in readiness, knowledge, and attitude ratings across groups, followed by the Mann-Whitney U test for pairwise comparisons when appropriate. The degree and direction of relationships between scores were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

A univariate logistic regression analysis was conducted for each relevant outcome variable to identify factors associated with poor readiness (scored < median score), poor knowledge (scored < median score), and negative attitudes (scored < median score) toward Mpox among the study population. Variables with a p-value < 0.20 in the univariate analyses were considered eligible for inclusion in the multivariable logistic regression models. This threshold was intentionally set above the conventional level of 0.05 to avoid prematurely excluding variables that may not show individual significance but could have an important effect in a multivariate context. Based on the univariate analysis, age, sex, years of experience, and place of work did not meet the inclusion criterion and were therefore excluded from the multivariable regression analysis.

A statistically significant p-value was defined as one that was less than 0.05.IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), was used to analyze the data.

Results

Of the 1220 participants who were approached and consented to participate, 127 were excluded due to either incomplete survey responses (failing to complete more than 50% of the survey) or not fulfilling eligibility criteria, primarily due to unemployment.

Profile of the participated healthcare professionals

Approximately, three-quarters of the participants (71.0%) were less than 35 years old. 616 (56.4%) of participants were females, 329 (30.1%) were physicians, 346 (31.7%) were pharmacists, and 418 (38.2%) were nurses. The majority of participants (78.7%) were employed in healthcare facilities located in major cities, while 21.3% working in rural areas. Of the participants, 16.1% had less than one year of medical experience, while 60.1% reported one to ten years of experience. The reported most common primary sources of information about Mpox were social media and health officials, by 29.8% and 26.7% of the participants, respectively (Table 1).

Readiness towards controlling Mpox

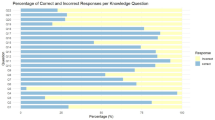

The readiness score ranged from 0 to 10 with an overall median score of 4 (IQR: 6). Notably, 58.0% of the participants demonstrated a high level (scored: ≥ median score) of readiness toward Mpox (Table 1). Among the ten items assessing readiness toward Mpox, the highest proportion of participants (68.3%) reported never received specific training on Mpox identification and management. This was followed by 63.9% expressing no confidence in their ability to manage Mpox cases, 58.6% reported never participated in simulation exercises for infectious disease outbreaks, including Mpox, and 54.1% reported never received training on how to use telemedicine/telepharmacy for patient consultation (Fig. 1).

Within each of the three healthcare occupational groups, a statistically significant difference in readiness scores was observed based on prior participation in pandemics (Fig. 2a). Nurses with prior experience had a higher median readiness score (8, IQR: 4) compared to those without experience (4, IQR: 4). Similarly, pharmacists with prior experience reported a median score of 8 (IQR: 4), whereas those without experience scored a median of 2 (IQR: 3). Physicians showed a median readiness score of 5 (IQR: 5.7) for those with prior experience, compared to 2 (IQR: 4) for those without. Notably, nurses with prior experience in previous pandemics demonstrated higher median readiness scores compared to pharmacists and physicians (Fig. 2). However, within each occupational group, there were no statistically significant differences in readiness scores between healthcare workers in rural and urban settings (p > 0.05) (Fig. 3).

Knowledge about Mpox

The knowledge score about Mpox ranged from 0 to 14 with an overall median score of 8 (IQR: 5). Overall, 53.9% of participants demonstrated a high level of knowledge about Mpox (scoring ≥ median) (Table 1). However, only 30.7% of participants were aware that there is no effective treatment for Mpox, 33.6% were aware of the availability of a vaccine, and 35.6% recognized that Mpox is not a newly emerging disease from 2024 (Table 2).

Attitude towards Mpox

Approximately 80.0% of participants highlighted the need for enhanced training and additional resources related to Mpox. Furthermore, 65.7% “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the existing infection control protocols in their healthcare settings were effective for managing Mpox, and 62.0% expressed willingness to receive the Mpox vaccine if available. Additionally, 60.6% of participants were satisfied with how health authorities managed information and communicated updates regarding Mpox outbreaks (Table 3).

Associations of participants’ profile with readiness and knowledge score towards Mpox

Among the measured characteristics, occupational group and experience in previous pandemics were significantly associated with readiness and knowledge scores toward Mpox. Nurses demonstrated a higher median readiness score (5, IQR: 5) compared to pharmacists (4, IQR: 6) and physicians (4, IQR: 6). Conversely, physicians had a significantly higher median knowledge score (8, IQR: 4) compared to pharmacists (5, IQR: 4) and nurses (7, IQR: 4). Healthcare professionals who had participated in previous pandemic responses exhibited significantly higher readiness (6, IQR: 5) and knowledge scores (8, IQR: 4) compared to non-participants, who recorded lower readiness (3, IQR: 5) and knowledge (7, IQR: 6) scores (Table 1).

Correlation between readiness and knowledge scores

No significant correlation was found between readiness and knowledge scores (r coefficient: 0.097, p > 0.05) (Table 4).

Factors associated with poor readiness, poor knowledge, and negative attitude

Lack of participation in containment of pandemics (AOR: 2.11, 95% CI : 1.60–2.78), not using digital health records at work (AOR: 3.14, 95% CI: 2.35–4.18), or relying mainly on social media (AOR: 2.39, 95% CI: 1.61–3.53) or online health portals (AOR: 2.21, 95% CI: 1.35–3.62) as primary Mpox information sources, were significantly associated with increased likelihood of exhibiting poor readiness towards Mpox. Those who obtain information through workshops were at reduced likelihood of having poor readiness (AOR: 0.36, 95% CI: 0.19–0.70). An increased likelihood of having poor was significantly associated with absence of previous-response experience (AOR: 1.40, 95% CI: 1.08–1.81) and using workshops as the chief information source (AOR: 2.55, 95% CI: 1.50–4.33).

No prior response involvement (AOR: 1.36, 95% CI: 1.04–1.78), not using digital health records (AOR: 1.56, 95% CI: 1.19–2.05), and relying primarily on colleagues for Mpox information (AOR: 1.73, 95% CI: 1.00–2.99) were significantly associated with increased likelihood of negative attitude while obtaining information from workshops was inversely associated with negative attitude (AOR: 0.32, 95% CI: 0.17–0.60) (Table 5).

Discussion

The present study evaluated the level of readiness, knowledge, and attitudes toward Mpox among healthcare professionals in Jordan, including physicians, nurses, and pharmacists. While participants generally demonstrated moderate knowledge and positive attitudes toward Mpox, their readiness to manage Mpox cases was found to be insufficient. This suggests that despite healthcare professionals being aware of the disease and motivated to treat it, they may not possess the necessary skills and readiness to respond effectively.

Several factors, both systemic and individual, likely contributed to this gap in readiness. On an individual level, inadequate training and limited opportunities to apply theoretical knowledge in real-world situations may play a significant role.

Psychological factors, including stress and uncertainty, play a critical role in determining readiness levels. Our study provides evidence of this relationship, as participants experiencing higher stress levels reported lower perceived readiness. Prior research20 has demonstrated a strong correlation between psychological resilience and vaccine acceptance, particularly among healthcare professionals such as nurses and physicians in Jordan. These findings underscore the importance of integrating targeted crisis-management training and stress-reduction strategies to enhance psychological preparedness. Strengthening resilience in this manner may bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and effective outbreak response, ultimately improving healthcare professionals’ ability to manage public health emergencies. At the systemic level, issues such as insufficient resources, limited strategic planning, and gaps in infectious disease infrastructure further hinder readiness. These findings align with a local study from Jordan15.

However, our findings diverge from the global literature, which often reports even poorer levels of knowledge and more negative attitudes toward Mpox among healthcare professionals21. Similarly, a cross-sectional survey in Southern Italy demonstrated that healthcare workers had an unsatisfactory level of knowledge about Mpox, and only nearly half showed positive attitudes toward the disease10. Moreover, a study conducted in Egypt also found that nurses’ readiness for Mpox was inadequate, pointing to a potential regional or even global crisis in healthcare workers’ readiness to manage the disease22. Furthermore, a study at a Specialized Referral Hospital in Ethiopia revealed that only about half of healthcare workers demonstrated good knowledge of Mpox, and fewer than half expressed a positive attitude toward the disease23. Jordan’s historical emphasis on communicable disease control, periodic infection-control training in certain hospitals, and professional development opportunities aimed at enhancing emergency response could all be contributing factors to the country’s relatively higher reported knowledge and attitudes, particularly among nurses. Still, as Martin Faye and colleagues24 suggest, prompt international collaboration is essential to contain the spread of Mpox and improve overall readiness. Despite these broader concerns, in this study, nurses in Jordan demonstrated higher readiness to face Mpox than physicians and pharmacists, which may be linked to the structured role that nurses play in Jordan’s healthcare system. Nurses often serve on the front lines, providing direct patient care and functioning as the first point of contact for screening and triage. Physicians, though often possessing greater theoretical knowledge, appeared less practically prepared. This discrepancy echoes observations from Yemen, where nurses were found to be more prepared than physicians, even though the latter had more comprehensive formal training. These findings are consistent with other research suggesting that practical exposure to crisis management protocols, emergency response systems, and guidelines improves readiness. Healthcare professionals with prior pandemic experience likely develop a procedural memory of useful tactics and actions, which they can readily apply when faced with similar challenges in the future25,26.

A significant proportion of participants reported a lack of specific training on Mpox identification and management, which is both alarming and expected. The low confidence in managing the condition, as reported by 63.9% of participants, can likely be attributed to this training gap. A systematic review has emphasized that well-structured training programs significantly enhance healthcare personnel’s ability to effectively manage disease outbreaks27. Such training not only improves professionals’ practical skills, such as the correct use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and critical care management but also bolsters their theoretical knowledge and confidence.

The study’s participants exhibited relatively a lack of substantial knowledge about the history of Mpox, available treatments, and vaccination options. In contrast, studies conducted in Egypt28 and China29 have shown that healthcare personnel in these countries possess a relatively acceptable level of knowledge regarding Mpox, which highlights a significant discrepancy compared to the findings in Jordan. Several contextual factors could explain this difference. First, healthcare professionals’ awareness is likely influenced by the frequency with which they encounter Mpox patients and their familiarity with the disease in different regions. For example, China has reported over 1,500 confirmed Mpox cases30, which may have prompted increased educational efforts and hands-on exposure to the disease among healthcare workers. Additionally, Egypt’s healthcare personnel may have a higher level of awareness due to its geographical proximity to the Democratic Republic of Congo, where Mpox is endemic, coupled with political and socio-economic ties that might foster more knowledge-sharing and readiness efforts. In Jordan, the comparatively lower number of confirmed Mpox cases may have resulted in fewer real-world encounters and a slower adoption of specialized training curricula. However, this also implies that healthcare professionals have less firsthand experience to develop preparation from.

The findings of this study indicate a positive attitude among healthcare professionals in Jordan towards identifying Mpox and how health authorities are managing the disease. This aligns with previous reports from Jordan15. In contrast, a study conducted in Lebanon found that less than a third of healthcare workers exhibited a satisfactory attitude towards Mpox18. These differences in attitudes, alongside disparities in knowledge, may be attributed to variations in organizational support, training opportunities, and exposure to infectious disease management in healthcare settings.

The findings of this study show that healthcare professionals who lack prior outbreak-response experience, do not use electronic health records, or depend mainly on social media, online portals, or colleagues for information are generally less prepared for Mpox, know less about the disease, and hold more negative attitudes toward it. In contrast, engaging with structured workshops tends to bolster readiness and foster more positive attitudes. This echoes broader observations that pandemic exposure boosts readiness: for example, Bangladeshi doctors showed a very positive preventive attitude toward Mpox31. The authors justified this finding that the physicians are already worn down by their experiences with COVID-19 and are aware of the repercussions of a pandemic31. Wei Zhu et al., found that healthcare workers with prior exposure to infectious disease outbreaks are better prepared for future emergencies. J. Odiase and colleagues32 explained these findings by reporting that healthcare professionals with prior experience in pandemic response are more adept at navigating the challenges presented by new outbreaks; they have quicker response times and more efficient use of resources. The findings of this study align with several studies during the COVID-19 pandemic that have shown that digital records can significantly enhance the management of infectious diseases33,34.

Study limitations and strengths

Potential limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings, including, first, the use of convenience and snowball sampling may have introduced selection bias, as participants who are more accessible or motivated could have been overrepresented, limiting the generalizability of the results to all healthcare professionals in Jordan. Second, despite efforts to standardize the questionnaire’s administration and content, the use of both online and in-person data collection methods may have introduced variability or potential biases between participant groups. Specifically, the online survey may have disproportionately attracted younger or more technologically proficient respondents, potentially skewing the results toward higher self-reported levels of knowledge and readiness compared to those who completed the survey in person. This methodological distinction underscores the need for cautious interpretation of findings and consideration of potential selection biases in future research. Third, the reliance on self-reported questionnaires introduces potential response biases, such as recall and social desirability bias. Fourth, conducting the survey in English may have created language barriers, though this was mitigated by the fact that medical degrees in Jordan are typically offered in English. Fifth, the cross-sectional design did not allow for the assessment of changes in attitudes, knowledge, or readiness over time, making it difficult to establish causality or evaluate long-term trends. Finally, the actual response rate could not be monitored, which limits the ability to assess non-response bias.

Despite these limitations, the study also has notable strengths. First, it provides valuable insights into the readiness, knowledge, and attitudes of healthcare professionals towards Mpox in Jordan, which can inform future interventions. Second, the inclusion of multiple healthcare professions (physicians, nurses, and pharmacists) strengthens the study’s ability to capture a broad spectrum of perspectives within the healthcare system. Another key strength of this study is its focus on a timely and relevant public health issue, the Mpox, during a period of heightened global concern. This allows the findings to contribute to ongoing efforts in improving readiness and response strategies for emerging infectious diseases in Jordan and similar contexts.

Conclusion

Healthcare professionals in this study demonstrated positive attitudes and moderate knowledge about Mpox, but their readiness was insufficient. A key finding was the widespread lack of specific training on Mpox, coupled with low confidence in managing the disease, which highlights a crucial gap in current healthcare training programs. Lack of prior experience in pandemic response, do not use electronic health records, or rely primarily on social media were more likely to be less prepared, have poor knowledge, and have more unfavorable attitude towards mpox. In contrast, engaging with structured workshops tends to bolster preparedness and foster more positive attitudes. These findings underscore the urgent need for comprehensive educational initiatives, enhanced training programs, and increased resources to strengthen healthcare professionals’ readiness and response to emerging infectious diseases like Mpox. Health authorities and key stakeholders must prioritize the implementation of structured educational interventions, including simulation-based training, to equip healthcare professionals with the practical skills, clinical competence, and confidence necessary for effective outbreak response and disease control.

Data availability

Upon official and justifiable request, data will be available from the corresponding author after obtaining all necessary approvals from the ethical review committee.

References

Duarte, P. M. et al. Unveiling the global surge of Mpox (Monkeypox): a comprehensive review of current evidence. Microbe 4, 100141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microb.2024.100141 (2024).

Araf, Y. et al. Insights into the transmission, host range, genomics, vaccination, and current epidemiology of the Monkeypox virus. Vet. Med. Int. 2024 (1), 8839830. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/8839830 (2024).

The World Health Orgnisation. WHO Director-General Declares the Ongoing Monkeypox Outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. Published 2022. Accessed October 8. (2024). https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/23-07-2022-who-director-general-declares-the-ongoing-monkeypox-outbreak-a-public-health-event-of-international-concern

The World Health Orgnisation. Multi-country Outbreak of Mpox, External Situation Report #42 – 9. Published 2024. Accessed December 5, 2024. November (2024). https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/multi-country-outbreak-of-mpox--external-situation-report--42--9-november-2024

Zayed, D., Momani, S., Banat, M. & Al-Tammemi, A. B. Unveiling the first case of Mpox in Jordan 2024: a look at the national preparedness and response measures. New. Microbes New. Infect. 62, 101488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2024.101488 (2024).

Jacob, R., McLean, D. O., Jason, E. & Zucker, M. Prevention and Treatment of Mpox. (2024). https://www.hivguidelines.org/guideline/sti-mpox/#:~:text=Primary prevention through immunization is,the global smallpox eradication effort.

Rincón Uribe, F. A., Godinho, R. C. & de Machado, S. Health knowledge, health behaviors and attitudes during pandemic emergencies: a systematic review. PLoS One. 16 (9), e0256731. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256731 (2021).

Amro, F. M., Rayan, A. H., Eshah, N. F. & ALBashtawy, M. S. Knowledge, attitude, and practices concerning Covid-19 preventive measures among healthcare providers in Jordan. SAGE Open. Nurs. 8, 23779608221106424. https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608221106422 (2022).

Nka, A. D. et al. Current knowledge of human Mpox viral infection among healthcare workers in Cameroon calls for capacity-strengthening for pandemic preparedness. Front. Public. Heal. 12, 1288139. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1288139 (2024).

Del Miraglia, G., Della Polla, G., Folcarelli, L., Napoli, A. & Angelillo, I. F. Knowledge and attitudes of health care workers about Monkeypox virus infection in Southern Italy. Front. Public. Heal. 11, 1091267. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1091267 (2023).

Shafei, A. M. et al. Resident physicians’ knowledge and preparedness regarding human Monkeypox: a cross-sectional study from Saudi Arabia. Pathogens 12 (7). https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12070872 (2023).

Kiros, T. et al. Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and associated factors of Mpox among healthcare professionals at Debre Tabor comprehensive specialized hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2024: a cross-sectional study. Heal Sci. Rep. 8 (1), e70371. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.70371 (2025).

Mohamed, M. G. et al. Assessment of knowledge, attitude, anxiety level and perceived mental healthcare needs toward Mpox infection among nursing students: a multi-center cross-sectional study. Glob Transitions. 6, 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.glt.2024.10.001 (2024).

Ahmed, S. K. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and willingness of healthcare workers in Iraq’s Kurdistan region to vaccinate against human Monkeypox: a nationwide Cross-Sectional study. Vaccines 11 (12). https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11121734 (2023).

Al Balas, S. et al. Assessing Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) towards Monkeypox among Healthcare Workers in JORDAN: A Cross-Sectional Survey. (2023).

Swed, S. et al. Knowledge of Mpox and its determinants among the healthcare personnel in Arabic regions: a multi-country cross-sectional study. New. Microbes New. Infect. 54, 101146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2023.101146 (2023).

Ahmed, S. K. How to choose a sampling technique and determine sample size for research: a simplified guide for researchers. Oral Oncol. Rep. 12, 100662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oor.2024.100662 (2024).

Malaeb, D. et al. Knowledge, attitude and conspiracy beliefs of healthcare workers in Lebanon towards Monkeypox. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 8 (2). https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8020081 (2023).

Yeshiwas, A. G. et al. Assessing healthcare workers confidence level in diagnosing and managing emerging infectious virus of human Mpox in hospitals in Amhara region, Northwest Ethiopia: multicentre institution-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 14 (7). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-080791 (2024).

Mahameed, H. et al. Previous vaccination history and psychological factors as significant predictors of willingness to receive Mpox vaccination and a favorable attitude towards compulsory vaccination. Vaccines 11 (5). https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11050897 (2023).

Jahromi, A. S. et al. Global knowledge and attitudes towards Mpox (monkeypox) among healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Health. 16 (5), 487–498. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihad094 (2023).

Sadek, B. N. et al. Are pediatric nurses prepared to respond to Monkeypox outbreak? PLoS One. 19 (4), e0300225. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0300225 (2024).

Beyna, A. T. et al. Assessment of healthcare workers knowledge and attitudes towards Mpox infection at university of Gondar comprehensive specialized referral hospital, Ethiopia. Front. Public. Heal. 13, 1527315. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1527315 (2025).

Faye, M. et al. Enhancing readiness in managing Mpox outbreaks in Africa. Lancet 403 (10446), 2779. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01022-5 (2024).

Blitstein-Mishor, E., Vigoda-Gadot, E. & Mizrahi, S. Navigating emergencies: A theoretical model of civic engagement and wellbeing during emergencies. Sustainability 15 (19). https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914118 (2023).

Doumi, R. et al. The effectiveness and benefits of disaster simulation training for undergraduate medical students in Saudi Arabia. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 15, 707–714. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S453879 (2024).

Nayahangan, L. J., Konge, L., Russell, L. & Andersen, S. Training and education of healthcare workers during viral epidemics: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 11 (5). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044111 (2021).

Amer, F. A. et al. Grasping knowledge, attitude, and perception towards Monkeypox among healthcare workers and medical students: an Egyptian cross-sectional study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 14, 1339352. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2024.1339352 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Mpox knowledge and vaccination hesitancy among healthcare workers in Beijing, China: a cross-sectional survey. Vaccine X. 16, 100434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvacx.2024.100434 (2024).

Ren, R. et al. The epidemiological characteristics of Mpox Cases - China, 2023. China CDC Wkly. 6 (26), 619–623. https://doi.org/10.46234/ccdcw2024.118 (2024).

Hasan, M. et al. Human Monkeypox and preparedness of Bangladesh: a knowledge and attitude assessment study among medical Doctors. J. Infect. Public. Health. 16 (1), 90–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2022.11.032 (2023).

Odiase, O. J. et al. Factors influencing healthcare workers’ and health system preparedness for the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study in Ghana. PLOS Glob Public. Heal. 4 (7), e0003356. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003356 (2024).

Satterfield BA, Dikilitas, O. & Kullo IJ. Leveraging the electronic health record to address the COVID-19 pandemic. Mayo Clin. Proc. 96 (6), 1592–1608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.04.008 (2021).

Ezenwaji, C. O., Alum, E. U. & Ugwu, O. P. C. The role of digital health in pandemic preparedness and response: securing global health? Glob Health Action. 17 (1), 2419694. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2024.2419694 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the students, faculty members, and health professionals who contributed to the data collection process.

Funding

This work did not receive any specific funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA and DA conceptualized and designed the study, oversaw the data collection process, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. RHA critically revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to revising and approving the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Al-Balqa Applied University (No. 2025/2024/1/112). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from each participant consented to voluntarily participate in the study.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

The authors used Quillbot tool ( https://quillbot.com/) for proofreading purposes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al Meslamani, A.Z., Abu-Naser, D. & Al-Rifai, R.H. Readiness, knowledge, and attitudes of healthcare professionals in Jordan toward Monkeypox: a cross-sectional survey. Sci Rep 15, 18178 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03051-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03051-2