Abstract

The Swedish Registry for Cognitive/Dementia Disorders (SveDem) follows the quality and equity of dementia care across Sweden. In this study, we investigated temporal trends in sex-based differences in the provision of dementia care. Outcomes were diagnostic work-up, assessments performed by health care professionals, medication use, and social support (defined as initiating contact with a social worker and/or support to relatives). Revisions in dementia diagnosis between baseline and follow-up were evaluated as a marker of diagnostic stability. We included 100,534 individuals diagnosed with dementia between 2008 and 2021 (median age 80 years, 58% women). Dementia registrations rose from 2008 to 2014, then declined after 2015. Alzheimer’s dementia was more frequent in women than men (35% versus 17%), while vascular dementia was less frequent (17% versus 21%). Small differences were observed in dementia care outcomes between sexes. Where differences reached statistical significance, effect sizes were minimal. Dementia diagnosis was revised in 5% of men and 4% of women over a median period of 11 months between baseline and first follow-up. Our results revealed negligible temporal trends in sex-based differences in dementia care among individuals included in the SveDem. However, as SveDem covers only about one third of Sweden’s dementia population, findings may not fully represent national trends.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sex-based differences in dementia have garnered increasing attention in recent years, with women presenting higher rates of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis1. While longer life expectancy in women partially explains this disparity, it does not account for all observed differences2,3. Sex differences in the risk conferred by ApoE4, hormonal changes after menopause1 and structural and functional brain differences may predispose women to distinct trajectories of cognitive decline1,2,5.

Recognizing sex-based differences in the diagnostics and care of dementia is essential for ensuring equitable healthcare1. Dementia care, as defined in this study, refers to the set of healthcare practices and support services provided to individuals living with dementia6,7. This includes the diagnostic work-up (e.g., cognitive assessments and neuroimaging), assessments conducted by healthcare professionals, prescription of medications, and support services such as engagement of social workers or family member support6,7. Previous research has identified significant disparities in the management of dementia care between men and women, including differences in intervention intensities and the use of diagnostic procedures8,9; however, these variations appear to be more closely related to age than to sex. In Sweden, individuals who live alone have also been shown to receive their diagnoses later, where a higher proportion of women than men live alone10. We also examined changes in diagnoses between baseline and follow-up, we considered this an indirect measure of diagnostic accuracy or stability since in the Swedish Registry for Cognitive/Dementia Disorders (SveDem), revisions or changes in diagnoses are more frequent among patients with unspecified dementia disorders11.

Given the observed sex-based differences in age-adjusted dementia incidence that are underpinned by biological factors and potential disparities in care, it is crucial to investigate whether these differences are mirroring differences in diagnostic practices and treatment approaches. The primary aim of this study was to explore temporal trends in sex differences in dementia care among patients registered in SveDem. A secondary aim was to investigate sex-based differences in the revision of dementia diagnosis between baseline and the one-year follow-up.

Methods

This register-based and explorative study followed the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement12.

Ethics

This register-based study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (registration number: 2021-06246-01; amendment number: 2024-03367-02 [date: 2024-06-13]). The Swedish Ethical Review Authority has waived the need for written informed consent for this study. Patients and caregivers were notified of their registration in SveDem and were given the option to opt-out. Under the Personal Data Act (SFS 1998:204), informed consent was not required for retrieving data from quality registers. Researchers received pseudonymized data from the registries, which included record IDs. The key codes for these record IDs were stored securely at the National Board of Health and Welfare and statistics Sweden. The research was performed in accordance with the ethical guidelines and regulations.

Design and study population

In this nationwide, explorative and register-based cohort study, we retrieved real-world data from Swedish registries. SveDem, a quality registry for cognitive/dementia disorders, collects data at the time of dementia diagnosis and during annual follow-up13. Established in 2007, it has become one of the largest clinical dementia registries globally, capturing ~ 29% of Sweden’s dementia diagnoses by 202114. In addition to recording variables such as age, sex, diagnostic work-up, dementia diagnoses, treatment, and support, the registry also collects data aligned with the Swedish national quality indicators for dementia care15. We also used data from the Swedish National Patient Register, which includes diagnoses since 2001, to calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)16. We obtained civil status and country of birth data from the Longitudinal Integrated Database for Health Insurance and Labor Market17. The unique Swedish personal identification numbers facilitated data linkages across these sources.

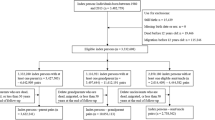

We included all individuals registered in SveDem who were diagnosed with dementia between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2021. Dementia diagnoses extracted from the registry included AD, mixed dementia, vascular dementia (VaD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), unspecified dementia, and other dementia types (Supplementary Table 1). Diagnoses were retrieved at baseline and the first follow-up. Individuals with missing data on diagnosis, or diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment were excluded.

Variables and definitions

All outcomes were binary. They reflected multiple aspects of dementia care. The outcomes were extracted from SveDem and categorized into four groups (Supplementary Table 2):

-

Dementia work-up—included the administration of one or more of the following tests:

-

o

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)18, the clock drawing test19, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)20, or the Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS)21. RUDAS and MoCA data were only included between 2018 and 2021, as these tests were not routinely administered before 2018.

-

o

Structural brain imaging was performed via computed tomography scan (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

-

o

Blood tests were part of the standard dementia workup.

-

o

In some cases, lumbar punctures were performed to analyze biomarkers in cerebrospinal fluid.

-

o

-

Assessments by an occupational therapist (OT), physiotherapist (PT), speech and language therapist, or neuropsychologist.

-

Medications included were cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine) or memantine in participants who had been diagnosed with either AD or mixed dementia. The use of antipsychotics was analyzed for all participants.

-

Support was defined as the initiation of contact with a social worker and/or the provision of support to relatives.

The CCI for each participant was calculated before their date of dementia diagnosis using a modified algorithm commonly applied in register-based research in Sweden22. Dementia diagnosis codes were excluded from the CCI calculations because all patients had a dementia diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

SveDem registrations per 100,000 inhabitants were calculated based on the number of dementia cases recorded in the database, including diagnoses from both primary and specialist care centers logged in 2008–2021. Population size by sex for each year (as of December 31, 2021) was obtained from Statistics Sweden, and the dementia registration rates were adjusted accordingly.

Binary logistic regression analysis was performed using generalized linear models with a logit link function to investigate sex-based differences in dementia care23. All outcomes were binary and corresponded to key components of dementia care, including diagnostic work-up, assessments by healthcare professionals, pharmacological treatment, and support services. Detailed definitions of these outcomes are provided in the “Variables and definitions” section.

One separate regression model was constructed for each outcome. All models included sex, year of diagnosis, age, and quadratic age (age2) as covariates to account for potential non-linear effects of age. These variables were selected based on the aims of the study and to account for age, a well-known and strong determinant of dementia progression and care needs. The inclusion of quadratic age allowed the models to capture more complex age-related patterns, recognizing that the relationship between age and diagnostic workup or treatment may not be strictly linear. To evaluate the significance of the interaction effect (sex × diagnosis year), we fitted a reduced model that excluded the interaction terms. A likelihood ratio test was used to compare the full model with the reduced one, assessing whether the interaction between sex and year of diagnosis significantly improved model fit. For all logistic regressions, we reported the proportions of men and women with corresponding 95% confidence intervals, p-values for sex-based differences, and year-wise differences.

In sensitivity analyses, we included the MMSE score and the CCI as additional covariates, as these represent key factors that are commonly used to determine the extent of diagnostic workups. MMSE was excluded from the primary models because it was also one of the outcomes of interest (i.e., whether MMSE was administered), and its inclusion could have introduced over-adjustment. However, to assess whether cognitive status might influence care practices, we explored its role in supplementary models. Similarly, CCI was not included in the primary models but was examined in sensitivity analyses to explore whether comorbidity burden may account for observed differences in dementia care. The models included sex, year of diagnosis, age, and quadratic age (age2).

Revisions to dementia diagnosis were analyzed by comparing baseline records with those from the first follow-up (median: 11 months; interquartile range [IQR]: 7 months) using cross-tabulation.

Data were analyzed using RStudio version 4.2.2 (R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with statistical significance set at 5%.

Results

Participant characteristics

The baseline SveDem sample included 101,071 registrations. After applying the inclusion criteria, 100,534 patients with dementia were retained (Supplementary Fig. 1). Median (IQR) age was 80 (10) years; 79 (10) years for men and 81 (10) years for women, 58% were women (Supplementary Table 3). Among both men and women, the number of dementia registrations in SveDem increased steadily between 2008 and 2014 before declining in 2015 (Fig. 1). Older age groups exhibited higher registration rates (Supplementary Fig. 2). Descriptive information stratified by sex for various aspects of dementia care, as well as the registration ratio, is presented in Table 1.

Dementia registrations in the Swedish Registry for Cognitive/Dementia Disorders (SvrDem) per 100,000 inhabitants in Sweden between 2008 and 2021, stratified by men, women, and total registrations. All participants with dementia registrations in SveDem were included. The gray box highlights the COVID-19 pandemic years in Sweden. The results were not standardized by age.

AD diagnosis was 25% more common among women than men, whereas VaD diagnosis was 19% more common in men than women, Table 1. Women had a relatively higher proportion of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnoses (Fig. 2), particularly in the older age groups (75–84 and ≥ 85 years), while men more frequently received diagnoses of vascular dementia (VaD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD), and other dementia types (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3). DLB and PDD were especially common among men aged 65–74 and 75–84. Additionally, unspecified and mixed dementia were more common among women in the oldest age group (≥ 85 years) (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Proportion of dementia diagnosis in the Swedish Registry for Cognitive/Dementia Disorders by type, sex, and year (2008–2021). The gray box highlights the COVID-19 pandemic years in Sweden. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; VaD, vascular dementia; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; PDD, Parkinson’s disease dementia; FTD, frontotemporal dementia.

Sex-based differences in dementia care

Multivariable binary logistic regression models, adjusted for the year of diagnosis, age, and quadratic age, revealed statistically significant sex-based differences across outcomes and changes in these differences over time (Table 2, Supplementary Figs. 4–7). However, the magnitude of these differences was generally small. The largest difference was found for performance of lumbar puncture (men 28.84% CI 28.66–29.01 versus women 25.56; CI 25.41–25.70). Between 2008 and 2021, statistically significant, but small changes were seen in the administration of MMSE, MRI/CT use, memantine and cholinesterase inhibitor prescriptions, and the initiation of contact with a social worker and/or the provision of support to relatives (Table 2). Sensitivity analyses adjusted for baseline MMSE score revealed similar patterns (Supplementary Table 4). Additional adjustments for CCI did not substantially change the overall pattern of sex-based differences in diagnosis and treatment (Supplementary Table 5). Both sensitivity analyses were adjusted for age.

Sex-based differences in changes to dementia diagnosis from baseline to first follow-up

A total of 48,433 patients had available baseline and first follow-up data, with a median interval of 11 months (IQR: 7 months) between assessments. Among these, 20,568 (43%) were men and 27,865 (57%) were women. Dementia diagnosis was revised in 5% of men (Table 3, Panel A) and 4% of women (Table 3, Panel B), resulting in an overall diagnostic revision rate of 4.5% (Supplementary Table 6).

Discussion

This nationwide cohort study in Sweden demonstrated a steady increase in dementia registrations between 2008 and 2014, followed by a decline after 2015. Women consistently exhibited higher registration rates than men, which may be attributed to several factors, including an overall higher incidence of dementia. Women had a higher proportion of AD, while men had higher proportions of VaD, DLB, PDD, and other dementia types. Comparisons between men and women revealed minimal differences in revised diagnosis. Slight variations were also observed regarding the use of dementia work up, assessments by health care professionals, medications, and support measures.

There may be several explanations for the overall decline in SveDem dementia registrations since 2015. First, it may be related to changes within the registry itself. The earlier increase in registrations was partially driven by a governmental initiative aimed at boosting primary care registrations through financial incentives between 2012 and 2014, followed by a return to pre-initiative levels once the program ended. It may also reflect reduced healthcare capacity24. Another sharp decline was observed between 2019 and 2020; however, this decline could be attributed to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which led to increased mortality among vulnerable individuals and closed memory clinics. We recently reported a decline in the average number of new dementia registrations across the pre-COVID-19, COVID-19, and post-COVID-19 periods25. The average nationwide monthly registrations decreased from 595 cases pre-COVID-19 to 415 cases during COVID-19, with a slight increase to 470 cases afterward. This downward trend was observed in both primary care and specialized memory clinics and persisted into the post-COVID-19 period25.

A true decline in the incidence of dementia between 2008 to 2021 may have occurred, as is supported by findings from several studies conducted in Europe and North America26,27. Those studies attributed the decrease in dementia incidence to improvements in cardiovascular health, education, and cognitive reserves over recent decades26,27,28. Better management of cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, as well as lifestyle improvements that include high levels of physical activity, have also been suggested to be major contributors26,29. Higher educational attainment and improved psychosocial working conditions over time may also have enhanced cognitive reserves, contributing to the observed decrease in dementia incidence26,27,30. However, the limited coverage of the SveDem registry makes it difficult to draw conclusions about the underlying dementia incidence in Sweden.

The decline in dementia registrations was similar across the sexes; however, the gap between women and men was greater in high-registration years (2013–2016). Although the gap narrowed slightly during the pandemic years, women remained more frequently registered in SveDem across all years. This difference may be attributed to the complex interplay of biological, social, and environmental factors2,10,31,32,33. The diagnostic rates of various dementia types remained stable over the study period, with notable sex-based differences in AD and VaD. The proportion of patients with AD was consistently higher for women than men, likely because of their longer average life expectancy. In contrast, VaD was slightly more common in men than women but remained generally stable over time. This may be because men have a higher incidence of stroke than women, particularly between the ages of 45 and 75 years34, which may increase their likelihood of developing vascular dementia later. A trend was observed in the diagnosis of unspecified dementia, with a noticeable increase beginning in 2012 followed by a decline starting in 2015. This pattern may be attributable to a governmental initiative implemented between 2012 and 2014 that used financial incentives to encourage primary care registrations.

Revisions to dementia diagnosis between baseline and the first follow-up were minimal. Both men and women most often experienced a shift from unspecified dementia at baseline to a diagnosis of AD at the first follow-up. This may be attributable to the diagnostic procedure for dementia. It is possible that initially, the patient received a “working” diagnosis in order to access social services or care while work-up was being conducted. For example, if patients were referred to specialist care or if more specialized tests (such as genetics, or PET) were required. As testing progressed, more information was gathered, discussions with relatives took place, and the diagnosis could be refined and specified. Another explanation for this shift may be that disease progression could lead to more pronounced and distinguishable clinical features over time, facilitating more definitive diagnoses35.

Our results partially align with those of Religa et al.8 in the early years of the SveDem registry, who first reported that men underwent more diagnostic tests, such as lumbar punctures and MRIs, than women. However, after adjusting for age, these differences disappeared, indicating that the disparities were age-related rather than sex-specific, with older women generally undergoing fewer tests8. Koikkalainen et al.36 highlighted the growing importance of imaging data in the differential diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases and the positive trend in MRI/CT usage can be interpreted as a marker of improved quality of dementia care. The observed differences in medication usage, particularly concerning the higher prescription rate of memantine in men than women, align with previous studies that reported sex-specific patterns regarding dementia treatment37. Although no differences have been reported between men and women concerning the cognitive and functional effectiveness of memantine38, the drug may be more commonly prescribed to men to better manage certain behavioral symptoms of AD, such as agitation1,39. The higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease in men than women may also influence the safety and prescribing patterns of cholinesterase inhibitors, which can have cardiac side effects40. Despite these concerns, several studies have demonstrated the beneficial outcomes associated with cholinesterase inhibitor use, including slower cognitive decline41, reduced stroke risk42, and lower all-cause mortality among patients with AD who have histories of myocardial infarction43. Our findings reinforce the complexity of sex and age influences on both diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in dementia care.

We found that caregivers of male participants diagnosed with dementia were more likely to receive support than those caring for female ones. This disparity may stem from societal and cultural factors that shape caregiving roles and support systems44. Moreover, we found significant temporal trends in family support which increased over time. The observed disparities in family support emphasize the need for tailored interventions to address the unique needs of individuals with dementia and their families throughout the diagnostic and treatment processes45.

This study had several strengths and limitations. One primary limitation is the potential for selection bias; SveDem covers ~ 30% of the expected dementia cases in Sweden11, and may not fully represent the national population with the disease. This limited coverage may have resulted in findings that do not accurately reflect the broader demographic and clinical characteristics of all patients with dementia in Sweden. This reduced coverage also makes it impossible to draw conclusions about the real incidence of dementia in Sweden or its changes over time. A second limitation is the retrospective nature of the analysis, which was inherent to the dataset used. A significant strength of this study is the large size and comprehensiveness of the SveDem registry, the largest clinical quality dementia registry of its kind. Nevertheless, the SveDem registry provides real-world data that reflect clinical practices in the diagnosis, treatment, and care of dementia, enhancing the likelihood of accurately capturing dementia management across both primary and specialized care facilities. The dataset spans 14 years, offering a comprehensive view of long-term trends in care practices between 2008 and 2021. A third limitation concerns the generalizability of our findings. Regional variations in registry participation and access to dementia care could limit the generalizability of the findings, as certain subgroups—such as individuals in rural areas or with lower socioeconomic status—may be underrepresented. This limited coverage may result in findings that do not fully capture the broader demographic and clinical characteristics of all individuals with dementia in Sweden. Moreover, Sweden’s tax-financed healthcare system ensures equitable access to healthcare services, suggesting that our findings may only apply to countries with similar healthcare systems.

In conclusion, our results revealed negligible temporal trends in sex-based differences in dementia care among individuals included in the SveDem. These results may indicate that Sweden’s gender-equality initiatives in healthcare have largely met their objective of delivering care that is both equitable and consistent. However, as SveDem covers only about one third of Sweden’s dementia population, findings may not fully represent national trends.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to Swedish and EU legislation as the datasets include sensitive health data. However, federated analyses are possible by contacting the senior researcher (sara.garcia-ptacek@ki.se).

References

Mielke, M. M. Sex and gender differences in Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Psychiatr. Times 35, 14–17 (2018).

Anstey, K. J. et al. Association of sex differences in dementia risk factors with sex differences in memory decline in a population-based cohort spanning 20–76 years. Sci. Rep. 11, 7710. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86397-7 (2021).

Levine, D. A. et al. Sex differences in cognitive decline among US adults. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e210169–e210169. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0169 (2021).

Altmann, A., Tian, L., Henderson, V. W., Greicius, M. D., Investigators, A. s. D. N. I. Sex modifies the APOE-related risk of developing Alzheimer disease. Ann. Neurol. 75, 563–573. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.24135 (2014).

Sindi, S. et al. Sex differences in dementia and response to a lifestyle intervention: Evidence from Nordic population-based studies and a prevention trial. Alzheimers Dement. 17, 1166–1178. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12279 (2021).

Murali, K. P., Carpenter, J. G., Kolanowski, A. & Bykovskyi, A. G. Comprehensive Dementia Care Models: State of the science and future directions. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 18, 7–16. https://doi.org/10.3928/19404921-20241211-02 (2025).

Warren, A. An integrative approach to dementia care. Front. Aging 4, 1143408. https://doi.org/10.3389/fragi.2023.1143408 (2023).

Religa, D. et al. Dementia diagnosis differs in men and women and depends on age and dementia severity: Data from SveDem, the Swedish Dementia Quality Registry. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 33, 90–95. https://doi.org/10.1159/000337038 (2012).

Sourial, N., Arsenault-Lapierre, G., Margo-Dermer, E., Henein, M. & Vedel, I. Sex differences in the management of persons with dementia following a subnational primary care policy intervention. Int. J. Equity Health 19, 175. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01285-2 (2020).

Ding, M. et al. Prevalence of dementia diagnosis in Sweden by geographical region and sociodemographic subgroups: a nationwide observational study. Lancet Reg. Health–Eur. 45 (2024).

SveDem. Svenska registret för kognitiva sjukdomar/demenssjukdomar - Årsrapport 2023 (2024).

Benchimol, E. I. et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 12, e1001885. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885 (2015).

Religa, D. et al. SveDem, the Swedish Dementia Registry—a tool for improving the quality of diagnostics, treatment and care of dementia patients in clinical practice. PLoS ONE 10, e0116538. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0116538 (2015).

SveDem. Svenska registret för kognitiva sjukdomar/demenssjukdomar, Årsrapport 2021., 1–124 (2022).

(Socialstyrelsen), T. N. B. o. H. a. W. Vård och omsorg vid demenssjukdom: Indikatorer 1–78 (Socialstyrelsen, 2020).

Ludvigsson, J. F. et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 11, 450. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-450 (2011).

Ludvigsson, J. F., Svedberg, P., Olén, O., Bruze, G. & Neovius, M. The longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA) and its use in medical research. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 34, 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00511-8 (2019).

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & McHugh, P. R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 12, 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 (1975).

Tuokko, H., Hadjistavropoulos, T., Miller, J. A. & Beattie, B. L. The Clock Test: A sensitive measure to differentiate normal elderly from those with Alzheimer disease. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 40, 579–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02106.x (1992).

Nasreddine, Z. S. et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53, 695–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x (2005).

Torkpoor, R., Frolich, K., Nielsen, T. R. & Londos, E. Diagnostic accuracy of the Swedish version of the Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS-S) for multicultural cognitive screening in Swedish memory clinics. J. Alzheimers Dis. 89, 865–876. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-220233 (2022).

Ludvigsson, J. F. et al. Adaptation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index for register-based research in Sweden. Clin. Epidemiol. 13, 21–41. https://doi.org/10.2147/clep.S282475 (2021).

Marschner, I., Donoghoe, M. W. & Donoghoe, M. M. W. Package ‘glm2’. Journal 3, 12–15 (2018).

Mattke, S. et al. Estimates of current capacity for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease in Sweden and the need to expand specialist numbers. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 11, 155–161 (2024).

Hoang, M. et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number of new dementia diagnoses and the quality of dementia diagnostics and treatment. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 1–9 (2024).

Ding, M., Qiu, C., Rizzuto, D., Grande, G. & Fratiglioni, L. Tracing temporal trends in dementia incidence over 25 years in central Stockholm, Sweden. Alzheimers Dement. 16, 770–778. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12073 (2020).

Wolters, F. J. et al. Twenty-seven-year time trends in dementia incidence in Europe and the United States. Neurology 95, e519–e531. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000010022 (2020).

Wu, J. et al. Can dementia risk be reduced by following the American Heart Association’s Life’s Simple 7? A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 83, 101788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2022.101788 (2023).

Rovio, S. et al. Leisure-time physical activity at midlife and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 4, 705–711. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(05)70198-8 (2005).

Hoang, M. T. et al. The impact of educational attainment and income on long-term care for persons with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: A Swedish Nationwide Study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 96, 789–800. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-230388 (2023).

Beam, C. R. et al. Differences between women and men in incidence rates of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 64, 1077–1083. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-180141 (2018).

Huque, H. et al. Could country-level factors explain sex differences in dementia incidence and prevalence? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. 91, 1231–1241. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-220724 (2023).

Geraets, A. F. J. & Leist, A. K. Sex/gender and socioeconomic differences in modifiable risk factors for dementia. Sci. Rep. 13, 80. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-27368-4 (2023).

Ospel, J., Singh, N., Ganesh, A. & Goyal, M. Sex and gender differences in stroke and their practical implications in acute care. J. Stroke 25, 16–25. https://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2022.04077 (2023).

Wetterberg, H., Najar, J., Rydberg Sterner, T., Kern, S. & Skoog, I. The effect of diagnostic criteria on dementia prevalence—a population-based study from Gothenburg, Sweden. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 32, 230–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2023.08.018 (2024).

Koikkalainen, J. et al. Differential diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases using structural MRI data. Neuroimage Clin. 11, 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2016.02.019 (2016).

Nebel, R. A. et al. Understanding the impact of sex and gender in Alzheimer’s disease: A call to action. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 1171–1183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.04.008 (2018).

Canevelli, M. et al. Sex and gender differences in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol. Res. 115, 218–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2016.11.035 (2017).

Tan, E. C. K. et al. Do acetylcholinesterase inhibitors prevent or delay psychotropic prescribing in people with dementia? Analyses of the Swedish Dementia Registry. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 28, 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2019.06.008 (2020).

Myers, K. D. et al. Effect of access to prescribed PCSK9 inhibitors on cardiovascular outcomes. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 12, e005404. https://doi.org/10.1161/circoutcomes.118.005404 (2019).

Xu, H. et al. Long-term effects of cholinesterase inhibitors on cognitive decline and mortality. Neurology 96, e2220–e2230. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000011832 (2021).

Tan, E. C. K. et al. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and risk of stroke and death in people with dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 14, 944–951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.011 (2018).

Shahim, B. et al. Cholinesterase inhibitors are associated with reduced mortality in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and previous myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 10, 128–136. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvad102 (2024).

Idorenyin Imoh, U. & Charity, T. Cultural and social factors in care delivery among African American caregivers of persons with dementia: A scoping review. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 9, 23337214231152000. https://doi.org/10.1177/23337214231152002 (2023).

Lindeza, P., Rodrigues, M., Costa, J., Guerreiro, M. & Rosa, M. M. Impact of dementia on informal care: A systematic review of family caregivers’ perceptions. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 14, e38–e49 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients, caregivers, reporting units, coordinators, and the steering committee of SveDem (https://www.ucr.uu.se/svedem/) for providing data for this study. The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

This work was supported by the Loo and Hans Osterman Foundation (#2023-01697), Karolinska Institutet’s Research Foundation Grants, Emil and Wera Cornell’s Foundation, the Swedish Research Council (VR Starting grant #2022-01425, Garcia-Ptacek), the Swedish state under the ALF agreement between the Swedish government and the county councils (ALFGBG-983604, FoUI-975207), the Swedish Dementia Foundation, Demensfonden, Alzheimerfonden, King Gustaf V and Queen Victoria’s Foundation, the Swedish Innovation Agency (Vinnova, grant #2021-02680), Lindhés Advokatbyrå AB, Innovative ways to fight Alzheimer´s disease - Leif Lundblad Family and others. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the preparation of the manuscript; or in the review or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: Abzhandadze, Religa, Garcia-Ptacek. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Abzhandadze, Hoang, Raaschou, Norgren, Mo, Molnar, Xu, Kananen, Åkerman, Religa, Eriksdotter, Garcia-Ptacek. Drafting of the manuscript: Abzhandadze. Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All co-authors. Statistical analysis: Abzhandadze, Norgren, Garcia-Ptacek, Mo. Obtained funding: Eriksdotter, Garcia-Ptacek, Abzhandadze, Norgren. Administrative, technical, or material support: Garcia-Ptacek, Eriksdotter, Åkerman. Supervision: Garcia-Ptacek.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abzhandadze, T., Hoang, M.T., Raaschou, P. et al. Temporal trends in sex differences in dementia care—results from the Swedish registry for cognitive/dementia disorders, SveDem. Sci Rep 15, 18890 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03055-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03055-y