Abstract

To investigate the relationship between respiratory sarcopenia with physical tests and a set of inflammatory biomarkers, seventy-one older women from the community with age 75 ± 7 years and BMI 26 ± 4 kg/m² were evaluated for appendicular lean mass using Dual X-ray Absorptiometry, respiratory muscle strength using an analog manuvacuometer, physical tests using handgrip strength, timed up and go and sit to stand in chair tests, and a panel of inflammatory biomarkers was measured, containing Adiponectin, BNDF, IFN, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, Leptin, Resistin, TNF and their soluble receptors sTNFr-1 and sTNFr-2. The analyzes suggest that older women with respiratory sarcopenia also had significantly low physical function and higher concentrations of sTNFr-2 (> 2241pg/ml), additionally respiratory muscle strength was inversely associated with sTNFr-2 concentrations (MIP: β = -0.48; R² = 0.24; p < 0.001; MEP: β = -0.35; R² = 0.12; p = 0.003). These results contribute to the discussion about the pathophysiology and to the strategies for diagnosing and monitoring respiratory sarcopenia in community-dwelling older women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Respiratory Sarcopenia (RS) is defined as the coexistence of respiratory muscle weakness and decreased respiratory muscle mass1. In addition to the known physical consequences of sarcopenia RS is accompanied by respiratory impairment, therefore more reduced physical capacity, and greater functional impairment2, also predictor of all-cause of mortality in community-dwelling older adults3.

The Japanese Society of Respiratory Care and Rehabilitation, with the Japanese Association of Sarcopenia and Frailty, Japanese Society of Respiratory Therapy, and Japanese Association of Rehabilitation Nutrition, published together the guidelines with recommendations for the assessment and classification of RS in the older1. According to the guidelines, the RS has stages, the possible RS is considered the first stage and diagnosed when only respiratory muscle strength is reduced without changes in muscle mass, while the probable RS, the second stage, occurs when respiratory muscle weakness is observed concomitantly with a decrease in muscle mass1,2.

To assess respiratory muscle mass, the gold standard is ultrasound or computed tomography are required, when these are not available, Dual X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA) can be used as an alternative. In this case, low respiratory muscle strength and low appendicular lean mass (ALM) are considered for the diagnosis of possible and probable RS1,2.

Regarding classic sarcopenia, there are already better-established diagnostic criteria4, with specific recommendations and ongoing studies on diagnostic biomarkers and related to pathophysiology5,6. However, for RS, the studies are relatively recent, specific recommendations are scarce, and screening strategies remain unexplored. Inflammatory biomarkers have been researched as a screening and diagnostic strategy for a variety of disorders, and they can point to potential pathophysiological pathways attached with the clinical result under investigation7.

There are few clinical studies and the results are initial, but there is evidence that older individuals with RS have worse muscular aspects when compared to whole-body sarcopenia. However, studies investigating inflammatory aspects remain unexplored. Inflammatory mediators related to sarcopenia have already been proposed, particularly when they are related to muscle mass and physical function reduction5,6,8,9,10,11. Biomarkers of frailty12, dementia13 and osteosarcopenia14,15 have also been recently investigated focusing on preventive, diagnostic and therapeutic actions. Nonetheless, research on sarcopenia that coexists with respiratory muscle weakness, i.e., respiratory sarcopenia, is still relatively new3. Therefore, research that investigate inflammatory pathways and indication to a possible early detection strategy is necessary, especially in respiratory sarcopenia where preventive interventions are unknow16.

Thus, this study aimed to investigate a potential inflammatory biomarker, and physical tests associated with the RS in community-dwelling older women. Additionally, to verify the diagnostic accuracy of these strategies in detecting RS. Contributing to screening measures and early detection of RS, as well as identifying potential pathophysiological mechanisms implicated.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional secondary and complementary analysis of the previously published study on sarcopenia and biomarkers5, was approved by the Institutional Ethics and Research Committee of Federal University of Jequitinhonha and Mucuri Valleys (nº protocol 1.461.306). The present study was edited following the guidelines of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)17 and conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sample

Participants were selected from the registries of all basic health units (BHU) in Diamantina, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Telephone calls, invites, and announcements were used to recruit participants at Diamantina’s basic health facilities, public spaces, and geriatric clinics. The inclusion criteria for participation were as follows: female subjects, over 65 years of age, functionally independent in the community and capable of performing evaluation procedures.

Exclusion criteria were individuals who demonstrated cognitive impairment, as measured by scores on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)18, with neurological sequelae, recent hospitalization (within the past three months), fractures in the upper or lower limbs (within the past six months), acute musculoskeletal disorders that could interfere with the proposed physical assessments, acute respiratory or cardiovascular diseases that would prevent the performance of respiratory measurements maneuvers, acute-phase inflammatory diseases, active neoplasms within the last five years, individuals under palliative care, and those using anti-inflammatory medications or drugs that affect the immune system.

Procedures

The assessments were conducted at the Laboratório de Fisiologia do Exercício (LAFIEX) and Laboratório de Inflamação e Metabolismo (LIM) at UFVJM, between June 2016 and June 2017. The evaluations were completed on three days, the first of which the eligibility criteria were met, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. On the second day, in the laboratory, the body composition, % of fat, trunk lean mass and ALM was assessed using Dual X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA)1,2,4.

Muscle strength was assessed using the handgrip strength test, in which the individual remains seated with support and positioned with the elbow flexed at 90 degrees and the wrist in neutral, applying a maximum isometric force on the Jamar dynamometer19,20. Physical performance was assessed using the timed up and go (TUG) test, in which the individual must get up from the chair, walk 3 m, go around the obstacle, return and sit down, while the time is recorded21. The 5x sit and stand (SGChair) test was also used, in which the individual must perform the task of sitting and standing from a chair for 5 repetitions while the time is recorded22.

Respiratory muscle strength was assessed by measuring the maximum inspiratory pressure (MIP) and the maximum expiratory pressure (MEP) using a manuvacuometer (model MV-150/300, Ger-Ar Comércio e Equipamentos Ltda.®)23. The participants were seated, with their feet flat on the floor, without support for the upper limbs, and using a nose clip. MIP was measured from the residual volume and MEP from total lung capacity. Acceptable measurements were those without air leaks and that obtained a variation of ≤ 10% of the maximum value found after tree measures. Between each measurement, a minimum interval of one minute was established for the volunteer to recover20.

Classification of respiratory sarcopenia

Following the classification recommendations of guidelines and cut-off points establishment for our population for respiratory muscle strength20, the sample was classified into 3 groups:1 – without RS; 2 – possible RS = low respiratory muscle strength: MEP < 77.5cmH2O; and 3 – probable RS = low respiratory muscle strength plus low ALM < 15 kg1,2.

Assessment of inflammatory biomarkers

On the third day, blood samples were collected at 8 a.m. from the antecubital fossa of the upper limb using disposable materials. Participants were required to fast for 10 h, refraining from consuming food, beverages, and medications during this period. The collection was performed using vacutainer bottles containing heparin in a sterile environment. Immediately after collection, the blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Following centrifugation, plasma samples were carefully extracted and stored at -80 °C for a duration of six months before analyzed.

The levels of adiponectin, brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), interleukin (IL) IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, tumoral necrosis factor (TNF), leptin, resistin, and soluble receptors of TNF (sTNFr)-1 and sTNFr-2 were analyzed using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent technique (ELISA) with the Duo-Set kit from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, USA. The plasma levels of interferon (IFN), IL-6 and IL-8 were measured using a cytometric bead array kit from BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The samples were acquired using a FACSCanto flow cytometer from BD Bioscience and analyzed using the FCAP array v1.0.1 software from Soft Flow24.

Statistical analyses

Sample size determination was carried out using the Openepi software. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 22.0 (SPSS Statistics; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and MedCalc Statistical Software (version 13.1, Ostend, Belgium) were used to perform statistical analyses. Considering a population of 2522 older women (> 65 years old) in the municipality of Diamantina, Minas Gerais, as registered in the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE—ibge.gov.br), and considering a sarcopenia prevalence of 16%25, an effect size of 0.80, a significance level of 5%, and a confidence interval of 80%, a sample size of 71 older women were estimated.

Data normality was verified by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and continuous variables were expressed as the mean and standard deviation (± SD) when parametric distribution, when non-parametric 95%CI. The ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallys-test for were used to compare the mean differences of continuous variables among subjects without and with possible and probable RS. Spearman correlations analysis was used to investigate the relationship between respiratory variables with physical tests and biomarkers.

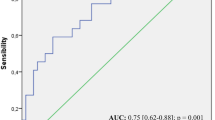

Binary logistic regression was conducted to verify the association between RS with physical tests and biomarkers, with percentage (%) of body fat serving as a model adjustment variable. Supplementary linear regression analysis was performed to verify the association between respiratory muscle strength and biomarker concentrations. Four assumptions were used in the linear regression analysis: linearity, residual distribution, homoscedasticity, and the absence of multicollinearity. Scatter plots were used to assess the behavior of the independent variables and residuals, and a histogram was used to look at the distribution of residuals. The variance inflation factor (VIF) values below 10.0 were used to define the absence of multicollinearity. Additionally, the autocorrelation of the variables was verified by the Durbin–Watson test and the values between 1.5 and 2.5 showed that there was no autocorrelation in the data. Data behavior analyzes were also carried out through the analysis of estimation curves. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were checked to test the sensitivity and specificity of the physical tests and biomarkers in discriminating individuals with respiratory sarcopenia. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) and the 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated for all tests and the optimal cut-off points were determined by the Youden Index. Statistical significance was set at 5%.

Results

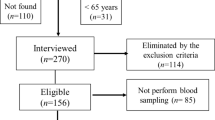

A total sample of 411 older women were initially identified based on their registration at the public health centers. However, 110 addresses were not located, and 31 individuals were found to be below the age requirement of 65 years. Subsequently, 270 older women were interviewed in their homes, but 114 of them did not attend the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Therefore, 156 community-dwelling older women remained eligible for the evaluation procedures, and 85 did not undergo blood sampling (Fig. 1).

Finally, in 71 community-dwelling older women the main of age was 75 ± 7 years, 24 ± 3 points on the MMSE, weight 59 ± 11 kg, height 1.50 ± 0.05 m, BMI 26 ± 4 kg/m², appendicular lean muscle mass of 15 ± 2 kg, trunk lean mass 16,7 ± 2 kg, HGS 19 ± 6 kg, SGchair 14,5 ± 4 s, TUG 11,5 ± 4 and respiratory muscle strength: MIP 72 ± 52 cmH20 and MEP 68 ± 32 cmH20. The possible RS was diagnosed in 16.9%, and probable RS in 57% of the participants.

Comparing the groups, it is possible to observe that the group with probable RS had lower weight, height, BMI, ALM, LTM, MIP, MEP, HGS, and physical performance, with the differences demonstrated in Table 1.

Regarding the analysis of panel of biomarkers, there was no variation in levels of IFN, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, Leptin, Resistin, TNF and sTNFr-1. As RS progresses, participants showed higher concentrations of Adiponectin, BDNF, IL-6 and IL-8, but the significant differences were found in plasma concentrations of sTNFr-2 between the groups without the condition (1847.4 ± 378.6pg/mL) and with probable RS (2241.2 ± 526.92pg/mL), as shown in Fig. 2:

Considering that possible RS is identified from the measurement of respiratory muscle strength, an additional exploratory analysis to evaluate the relationship between respiratory variables and HGS, SGChair, TUG and plasma concentrations of sTNFr-2 was conducted. Spearman’s correlation analysis showed that there was a significant correlation between MIP and HGS (r = 0.55; p<0.001), SGChair (r = -0.59; p<0.001) and TUG test (r = -0.51; p<0.001), and between MEP and HGS (r = 0.42; p<0.001), SGChair (r = -0.46; p<0.001) and TUG test (r = -0.51; p<0.001).

Regarding the biomarkers analyses, there was a significant correlation between MEP (r = -0.421; p <0.001) and MIP (r = -0.365; p = 0.002) with the sTNFr-2 concentrations. No other marker showed a significant correlation with respiratory muscle strength. So, estimation curve and linear regression analyzes were conducted to verify the relationship between the MIP and MEP with sTNFr-2 levels. The inverse association curve was the model best adjusted to MEP and MIP with the sTNFr-2 (Figure 3ab).

A proportional inverse relationship was observed between the MEP (Fig. 3a) and MIP (Fig. 3b) with sTNFr-2. Thus, a linear model could be applied to explain how MEP (Fig. 3c) and MIP (Fig. 3d) is a function of the inverse of the sTNFr-2 concentration. With evidence that MEP is a measure more effective predictor of Sarcopenia than MIP20,26, we conducted a linear regression analysis, adjusted by BMI, with MEP acting as dependent variable and the biomarker panel as independent variables, the best values found were only sTNFr-2 remaining in the model, explaining 21% of the MEP variations [R = 0.46; R² = 0.21; β = -0.46; (95%CI = -0.48 – -0.18) p < 0.001].

To verify the association between the probable RS with physical test and inflammatory biomarkers, a univariate logistic regression analysis was performed, and the results demonstrated a significant association between RS and BMI, LTM, HGS, TUG and sTNFr-2 concentrations, as summarized in Table 2:

Applying the Youden index, we find that the appropriate cutoff point for detecting RS, with 70% sensitivity and 70% positive predictive power, 10.2 s was the cutoff point for detecting RS using the TUG as an assessment instrument. Using plasma levels of sTNFr-2, with 70% specificity and 74% positive predictive value, the cutoff point found was 2034 pg/ml. Suggesting that both methods can be applied in screening or diagnostic strategies for RS in community-dwelling older women.

Discussion

Our results demonstrated that, as RS progresses, older women exhibit lower weight, height, BMI, muscle mass, hand grip strength, respiratory muscle strength, performance on the SGChair, increased time on the TUG test, and higher plasma levels of sTNFr-2. RS was found to be significantly associated with BMI, TLM, HGS, TUG performance, and sTNFr-2 concentrations. Both TUG performance and sTNFr-2 levels, demonstrated acceptable diagnostic accuracy for identifying RS in this sample. No significant differences were observed between groups in age and cognitive function, allowing us to speculate that RS may affect community-dwelling older women regardless of advanced age or cognitive impairment

Since RS was described, the recommended gold standard for assessing respiratory muscle mass has involved the use of technological equipment, which is often high-cost and has limited availability3. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is an alternative for multicompartmental body composition assessment device that provides TLM, expressed in kilograms. Because RS is characterized by the loss of respiratory muscle mass, it is reasonable to suggest that the reduction in TLM is associated with this condition. In our results, although TLM was found to be associated with RS, it did not demonstrate acceptable diagnostic accuracy for screening probable RS. Advances in research are needed to investigate whether TLM can be useful in the diagnosis and understanding of RS.

he HGS is a test widely used as a representative measure of global muscular strength27. TUG test21 and SGChair4 for evaluated lower limb performance in older people, both in the clinic and in research for the screening and diagnosis of sarcopenia in older adults4,20,28. As expected, our analyses demonstrated that older women with probable RS also presented lower muscle strength and physical performance, as in whole-body sarcopenia20,23,29. Association analyses showed that RS was associated with HGS and performance on the TUG test, with the latter demonstrating acceptable accuracy for screening RS when the TUG test duration exceeded 10.2 s. It is important to highlight that the cutoff point identified in our study differs substantially from the recommendations of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2)4, which suggests a cutoff point of 20 s on the TUG test for screening or diagnosing whole-body sarcopenia.

The suggested mechanisms for reduced physical performance in RS involve the weakening and loss of respiratory muscle mass, which lead to increased fatigue in these muscles and compromised respiratory dynamics2,16. These alterations reduce the efficiency of oxygen uptake, distribution, and utilization, directly impacting the ability to sustain physical activity30,31. The cumulative effect includes a decline in exercise tolerance and a progressive reduction in overall muscle mass, strength, and physical performance30. Furthermore, chronic respiratory muscle fatigue may exacerbate systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, which are known contributors to RS30. Reduced pulmonary function can also result in insufficient oxygen delivery to peripheral tissues, further impairing muscle metabolism and functional capacity16,30,32. These interrelated mechanisms underline the multifactorial characteristic of RS and its significant impact on the health and quality of life of older adults.

In this panel of biomarkers, the only associated with probable RS was sTNFr-2, and the inverse proportionality relationship demonstrates that the sTNFr-2 concentrations increase proportionally to the reduction in respiratory muscle strength. Indicating that there may be an inflammatory component in RS, and older women with probable RS has a greater inflammatory response characterized by significantly higher concentrations of sTNFr-2. The diagnostic accuracy analysis showed that 2034pg/ml may be a value capable of indicating the presence of RS.

STNFr-2 is an inflammatory mediator, which also has been associated with chronic and inflammatory respiratory conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease24, and the high blood concentration of sTNFr-2 is related to other respiratory conditions such as to greater susceptibility to pneumococcal infection, and to fungal infection in cystic fibrosis33,34. In the context of chronic inflammation, the literature shows a dichotomous and complex role of sTNFr-235. There is evidence that this cytokine promotes the accumulation of natural killer (NK) cells and controls the action of TNF in controlling and exacerbating inflammation, compromising the regeneration of muscle tissue35,36. Studies investigating its therapeutic action have shown that suppression of sTNFr-2 contributes to an inflammatory environment that hinders the occurrence of cancer metastasis36. Based on these results presented, we can speculate that sTNFr-2 may be an inflammatory mediator that is increased in inflammatory chronic conditions, including when occurs with respiratory component24,33,34,37.

As with other studies on RS, the results should be analyzed with caution, as it is still unclear whether RS is a consequence of whole-body sarcopenia or if they are distinct conditions. Morisawa et al. (2021) speculate on the possibility of RS occurring before full-body sarcopenia32, but there is currently no evidence supporting that RS is independent of full-body sarcopenia1. It is established that full-body sarcopenia can cause RS, but whether RS can lead to full-body sarcopenia remains hypothetical1. This suggests different outcomes, either sarcopenia and RS are distinct and have similar clinical implications, or it is just a reflection or consequence of classic sarcopenia.

It has been speculated that age-related decline in respiratory function precedes a decline in skeletal muscle mass30,31. This theory suggests that the decrease in respiratory muscle mass and strength occurs before a reduction in exercise tolerance, mainly due to reduced oxygen carrying capacity, skeletal muscle fatigue in the extremities, and general muscle weakness30,31. In this line, Umehara et al. 2024, compared older individuals with RS sarcopenia with older with sarcopenia without a respiratory component, and found that in the probable RS group, the older individuals had lower HGS, lower lean muscle mass index, greater frailty, and poorer muscle quality30. Kera et al. (2023) demonstrated that RS was a predictor of all-cause mortality in community-dwelling older adults. However, they acknowledged that 5-year mortality rates appeared to be strongly influenced by whole-body sarcopenia3. Therefore, even the studies are initial, differences between older individuals with sarcopenia and RS have already been reported and new studies are needed to clarify more profound the similarities and differences between these conditions.

Based on our findings, we hypothesize that subtle differences may exist in inflammatory aspects, given that RS is not characterized by significantly elevated concentrations of the same inflammatory mediators6,38,39,40,41. This may indicate differences in inflammatory pathological pathways or distinct interactions between inflammatory cells8,42,43. Therefore, further studies are required to clarify the gaps regarding the potential differences between whole-body sarcopenia and RS, especially in inflammatory terms.

As sTNFr-2 is a cytokine with dichotomous characteristics in the inflammatory environment36, is reasonable to suspect that subjects with probable RS have an increased systemic inflammatory response, contributes to concomitant losses in respiratory muscle strength and muscle mass. Research advances are needed to clarify the mechanisms, specific pathways and role of sTNFr-2 in RS.

Additionally, the results presented should be considered preliminary, and several limitations must be acknowledged. The modest sample size, consisting solely of older women from the community, limits the generalizability of the findings to men, institutionalized individuals, or hospitalized patients. The research design does not permit the establishment of a cause-and-effect relationship. The inclusion of only women may be considered both a limitation and a strength, as inflammatory conditions are known to vary by gender, particularly with advancing age. Another limitation is the absence of a gold-standard evaluation of respiratory muscle mass, as the sample was not assessed using technologically advanced instruments with objective accuracy to measuring respiratory mass and confirm the presence of RS, in accordance with current guidelines. New studies with larger samples, which explore multimorbidity patterns, including populations with cardiovascular or respiratory disease, and explored diet and level of physical activity are necessary to confirm the present findings, since these are aspects that can influence systemic inflammation, especially in aging. Despite these limitations, the study provides information that may be useful in the clinical context, in exploring the pathophysiology of RS, and in guiding future research on inflammation and RS.

Conclusion

Probable respiratory sarcopenia was associated with poor TUG test performance and higher plasma levels of sTNFr-2. These strategies also demonstrated reasonable diagnostic accuracy for indicate this condition, presenting a simple test and promising biomarker for use as an alternative for early diagnosis and contributing to the development of knowledge about inflammation and pathophysiology of chronic respiratory conditions in older people.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the privacy guarantee of the data collected individually.

References

Sato, S. et al. Respiratory sarcopenia: A position paper by four professional organizations. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.14519 (2023).

Nagano, A. et al. Respiratory sarcopenia and sarcopenic respiratory disability: concepts, diagnosis, and treatment. J. Nutr. Health Aging. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-021-1587-5 (2021).

Kera, T. et al. Respiratory sarcopenia is a predictor of all-cause mortality in community-dwelling older adults—The Otassha study. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13266 (2023).

Cruz-Jentoft, A. J. et al. 2019 Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis European working group on sarcopenia in older people 2 (ewgsop2), and the extended group for ewgsop2. Age Ageing 48 16–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy169

da Costa Teixeira, L. A. et al. Inflammatory biomarkers at different stages of sarcopenia in older women. Sci. Rep. 13 10367. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-37229-3 (2023).

Jones, R. L., Paul, L., Steultjens, M. P. M. & Smith, S. L. Biomarkers associated with lower limb muscle function in individuals with sarcopenia: a systematic review. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13064 (2022).

Aronson, J. K. & Ferner, R. E. Biomarkers—a general review. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpph.19 (2017).

Curcio, F. et al. Biomarkers in sarcopenia: A multifactorial approach. Exp. Gerontol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2016.09.007 (2016).

Kalinkovich, A. & Livshits, G. Sarcopenia 2015 the search for emerging biomarkers. Ageing Res. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2015.05.001

Pan, L. et al. Inflammation and sarcopenia: A focus on circulating inflammatory cytokines. Exp. Gerontol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2021.111544 (2021).

Ladang, A. et al. Biochemical markers of musculoskeletal health and aging to be assessed in clinical trials of drugs aiming at the treatment of sarcopenia: consensus paper from an expert group meeting organized by the European society for clinical. Calcif Tissue Int. 112, 197–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-022-01054-z (2023).

ÖztorunHS et al. Attention to osteosarcopenia in older people! It May cause cognitive impairment, frailty, and mortality: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Geriatr. Gerontol. https://doi.org/10.4274/ejgg.galenos.2021.2021-6-2 (2022).

Farr, O. M., Tsoukas, M. A. & Mantzoros, C. S. Leptin and the brain: influences on brain development, cognitive functioning and psychiatric disorders. Metabolism. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2014.07.004 (2015).

Inoue, T. et al. Exploring biomarkers of osteosarcopenia in older adults attending a frailty clinic. Exp. Gerontol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2022.112047 (2023).

Fathi, M. et al. Association between biomarkers of bone health and osteosarcopenia among Iranian older people: the Bushehr elderly health (BEH) program. BMC Geriatr. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02608-w (2021).

Miyazaki, S., Tamaki, A., Wakabayashi, H. & Arai, H. Definition, diagnosis, and treatment of respiratory sarcopenia. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0000000000001003 (2024).

Inacio Bastos, F. Maria Ferreira Magnanini Cosme Marcelo Furtado Passos da Silva II MI, Oswaldo Cruz Rio de Janeiro F, Malta M. Monica Malta I Leticia Oliveira Cardoso II STROBE initiative: guidelines on reporting observational studies. (2010).

Bertolucci, P. H. F., Brucki, S. M. D., Campacci, S. R. & Juliano, Y. O Mini-Exame do Estado mental Em uma população geral: impacto Da escolaridade. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0004-282x1994000100001 (1994).

de Souza Vasconcelos, K. S. et al. Handgrip strength cutoff points to identify mobility limitation in community-dwelling older people and associated factors. J. Nutr. Health Aging https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-015-0584-y (2016).

Soares, L. A. et al. Accuracy of handgrip and respiratory muscle strength in identifying sarcopenia in older, community-dwelling, Brazilian women. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-28549-5 (2023).

Filippin, L. I., Miraglia, F., Teixeira, V. N. & de Boniatti, O. MM. Timed Up and Go Test No Rastreamento Da Sarcopenia Em Idosos Residentes Na Comunidade (Revista Brasileira de Geriatria e Gerontologia, 2017).

Bohannon, R. W., Bubela, D. J., Magasi, S. R., Wang, Y. C. & Gershon, R. C. Sit-to-stand test: performance and determinants across the age-span. Isokinet. Exerc. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3233/IES-2010-0389 (2010).

PedreiraRBS et al. Are maximum respiratory pressures predictors of sarcopenia in the elderly? Jornal Brasileiro De Pneumologia. https://doi.org/10.36416/1806-3756/e20210335 (2022).

Neves, C. D. C. et al. Inflammatory and oxidative biomarkers as determinants of functional capacity in patients with COPD assessed by 6-min walk test-derived outcomes. Exp. Gerontol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2021.111456 (2021).

DizJBM et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia in older Brazilians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12720 (2017).

Sawaya, Y. et al. Sarcopenia is not associated with inspiratory muscle strength but with expiratory muscle strength among older adults requiring long-term care/support. PeerJ https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.12958 (2022).

de Souza Moreira, B. et al. Nationwide handgrip strength values and factors associated with muscle weakness in older adults: findings from the Brazilian longitudinal study of aging (ELSI-Brazil). BMC Geriatr. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03721-0 (2022).

Kim, C. R., Jeon, Y. J. & Jeong, T. Risk factors associated with low handgrip strength in the older Korean population. PLoS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214612 (2019).

Marcon, L., de Melo, F., de Pontes, R. C. & FL Relationship between respiratory muscle strength and grip strength in institutionalized and community-dwelling older adults. Geriatr. Gerontol. Aging. https://doi.org/10.5327/z2447-212320212000148 (2021).

Umehara, T., Kaneguchi, A., Yamasaki, T. & Kito, N. Exploratory study of factors associated with probable respiratory sarcopenia in elderly subjects. Respir Investig. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESINV.2024.06.009 (2024).

OcanaPD et al. Age-related declines in muscle and respiratory function are proportionate to declines in performance in master track cyclists. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-021-04803-4 (2021).

Morisawa, T. et al. The relationship between sarcopenia and respiratory muscle weakness in community-dwelling older adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413257 (2021).

Patel, D., Dacanay, K. C., Pashley, C. H. & Gaillard, E. A. Comparative analysis of clinical parameters and sputum biomarkers in Establishing the relevance of filamentous Fungi in cystic fibrosis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2020.605241 (2021).

Xu, R. et al. TNFR2 + regulatory T cells protect against bacteremic peumococcal pneumonia by suppressing IL-17A-producing Γδ T cells in the lung. Cell. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112054 (2023).

McCulloch, T. R. et al. Dichotomous outcomes of TNFR1 and TNFR2 signaling in NK cell-mediated immune responses during inflammation. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54232-y (2024).

Williams, R. O., Clanchy, F. I. L., Huang, Y. S., Tseng, W. Y. & Stone, T. W. TNFR2 signalling in inflammatory diseases. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BERH.2024.101941 (2024).

Ahmad, S. et al. The key role of TNF-TNFR2 interactions in the modulation of allergic inflammation: A review. Front. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02572 (2018).

Augusto Costa Teixeira, L. et al. Clinical medicine adiponectin is a contributing factor of low appendicular lean mass in older community-dwelling women: A cross-sectional study. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11237175 (2022).

Komici, K. et al. Adiponectin and sarcopenia: A systematic review with Meta-Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.576619 (2021).

Lustosa, L. P. et al. Comparison between parameters of muscle performance and inflammatory biomarkers of non-sarcopenic and sarcopenic elderly women. Clin. Interv Aging. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S139579 (2017).

Bian, A. L. et al. A study on relationship between elderly sarcopenia and inflammatory factors IL-6 and TNF-α. Eur. J. Med. Res. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-017-0266-9 (2017).

Park, M. J. & Choi, K. M. Interplay of skeletal muscle and adipose tissue: sarcopenic obesity. Metabolism. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2023.155577 (2023).

Severinsen, M. C. K. & Pedersen, B. K. Muscle–Organ crosstalk: the emerging roles of myokines. Endocr. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1210/ENDREV/BNAA016 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the old woman participants as study volunteers, to the evaluation team and the Health Department and the Basic Health Units of the municipality of Diamantina.

Funding

We would like to thank the support provided by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG APQ-00277-24, APQ-04955-23, APQ-01328-18), the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq-402574/2021-4 and CNPq-151412/2024-3) and the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de nível Superior – Brazil (CAPES PROEXT-PG 88881.926996/2023-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors know and meet the criteria for authorship, as stated in the uniform requirements for manuscripts sent to biomedical journals (ICMJE). L.A.C.T. was responsible to conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; resources; software; supervision; validation; visualization; roles/writing - original draft; and writing - review & editing. A.C.B. contribution to conceptualization; methodology; visualization; and critical review.L.A.S. contribution to conceptualization; formal analysis; methodology; visualization; and writing - review & editing. M.F.S.M. with design, execution, interpretation of the study and critical review.J.N.P.N. contribution to design, execution, draft, interpretation of the study and critical review. A.A.V. with design, execution, interpretation of the study and critical review.A.N.P. collaborated with conceptualization, data curation; investigation; methodology; project administration; supervision; validation; visualization; roles/writing - original draft; and writing - review & editing.P.H.S.F. contributing to design, interpretation of the study and critical review.R.T. contributing to design, interpretation of the study and critical review.V.A.M. with conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; resources; software; supervision; validation; visualization; roles/writing - original draft; and writing - review & editing; and A.C.R.L. was responsible to conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; software; supervision; validation; visualization; roles/writing - original draft; and writing - review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

da Costa Teixeira, L.A., de Carvalho Bastone, A., Soares, L.A. et al. Physical and inflammatory aspects associated to respiratory sarcopenia in community-dwelling older women. Sci Rep 15, 18310 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03137-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03137-x