Abstract

This study aimed to calculate stratified normative scores of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in an adult population in Singapore, accounting for key demographic influences. Demographic data and MoCA scores of 1,103 healthy adults (aged 21 to 97) were obtained from a community health study conducted in central Singapore. Factors associated with MoCA scores were identified using multiple linear regression and β coefficients were used to estimate normative MoCA scores across strata. Model performance was assessed using five-fold cross-validation. Normative reference scores were calculated and stratified by age group, education level, and ethnicity to reflect typical MoCA performance across demographic groups. The final regression model had an adjusted R2 of 0.284 (p < 0.001), with age group (β = -0.325 to -2.312) and education level (β = 1.783 to 4.206) accounting for the majority of the explained variance (R2 = 0.271). Ethnicity also remained a significant factor in the model, with lower scores observed among Malay (β = -1.248) and Indian (β =-0.795) participants compared to Chinese. Among the 64 demographic combinations of age group, education level and ethnicity, the lowest normative score (20.0) was derived for Malay individuals aged ≥ 75 years with no formal education. MoCA scores varied systematically with age, education level, and ethnicity in the study population. The resulting stratified reference scores provide clinicians and researchers a useful context for interpreting individual MoCA performance relative to demographically similar peers in Singapore’s adult population. However, these reference scores are not diagnostic thresholds and should be interpreted with caution until validated against clinically diagnosed cognitive impairment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dementia is a prevalent neurocognitive disorder that represents a significant public health challenge, particularly as populations age worldwide. Its prevalence among adults aged 60 years and above varies notably depending on diagnostic criteria. According to a recent study in Singapore, while 4.6% met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) classification criteria, this figure rose to 10% when using the more comprehensive 10/66 dementia diagnosis protocol1. The condition’s economic impact is substantial, with annual costs reaching 532 million Singapore dollars2.

The urgency of addressing dementia is underscored by Singapore’s demographic shifts. The proportion of elderly residents aged 65 and above increased significantly from 12.4% in 2014 to 19.9% in 20243. This aging trend highlights the critical importance of early detection, particularly at the prodromal stage, when targeted interventions may help slow cognitive decline.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) serves as a crucial warning sign, representing an intermediary state between normal cognition and dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease. Studies of both clinical and community samples have demonstrated significant rates of conversion from MCI to dementia4. To identify cognitive impairment early, researchers have developed various screening tools, with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) emerging as one of the newest and most promising instruments.

The MoCA is a brief single page inventory specifically developed to differentiate MCI from normal age-related cognitive decline. Developed by Nasreddine et al.5 as an alternative to the widely-used Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), the MoCA’s comparative effectiveness has yielded mixed results in the literature. While some studies found comparable performance between the two instruments6 or similar efficacy among educated subjects7, the majority of research indicates that MoCA demonstrates superior screening capabilities across various settings6,8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

Given the MoCA’s development in a Canadian context, researchers worldwide have undertaken validation studies to enhance its cross-cultural applicability, including translations and adjustment of cut-off scores for different populations15,16. The Singapore version of MoCA (mocatest.org) was culturally adapted from the original version and has been translated into Chinese and Malay for local use10. A local study conducted by Dong et al.6 established the discriminant validity of MoCA in a Singapore clinical sample and demonstrated MoCA’s superior ability to detect multiple-domain MCI compared to the MMSE. However, two studies suggested varying optimal cut-off scores for MCI screening − 24/25 by Liew and colleagues17 versus 28/29 by Ng and colleagues7 in clinical samples, and 22/23 in mixed clinical-community samples. These disparities may reflect differences in sample sizes, demographic characteristics, and the varying severity of cognitive impairment between clinical and community populations.

Prior literature suggests many socio-demographic factors influence an individual’s cognitive test performance, with age and education being the most prominently reported factors18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. One study even found age and education explained 49% of the variance in MoCA performance19. Other demographic factors, such as ethnicity, marital status, and lifestyle factors (e.g. smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity), and psychosocial factors (e.g., social isolation, loneliness, depression) have been less systematically examined, particularly in multi-ethnic populations like Singapore.

A study conducted in China established age-specific MoCA cut-off scores for older adults, highlighting a gradual declines in cognitive performance across age brackets26. Locally, Lim et al. reported unexplained ethnic differences in MMSE performance among older adults with lower-education levels, suggesting the need for ethnicity-specific adjustments when interpreting cognitive screening results27. Similar ethnic variations may apply to MoCA performance; however, no large-scale normative study in Singapore has stratified MoCA scores by ethnicity, despite the country’s ethnically diverse population comprising Chinese, Malay, Indian, and other ethnic groups. Notably, research from Malaysia - a neighboring country with similar ethnic compositions - also reported ethnic disparities in cognitive test performance28, reinforcing the need for ethnicity-tailored normative data. In addition, prior studies have documented that social isolation is associated with cognitive decline or poorer cognitive performance29,30, while healthy lifestyle serve as protective factors for cognitive deterioration31,32,33.

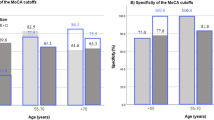

Currently, the MoCA’s screening protocol only adjusts for education, adding one point for individuals with limited formal education. Specifically, Nasreddine et al. recommended adding one-point to the total MoCA scores (if < 30) for individuals with ≤ 12 years of formal education5. In Singapore, this adjustment has been applied to those with ≤ 10 years of formal education34. However, evidence by Gagnon et al.35 suggests that while this adjustment may improve specificity, it risks reducing sensitivity, potentially leading to increased false negatives. This limitation highlights the necessity of multifactorial normative data that specific to discrete combinations of age, education, ethnicity, and other relevant factors.

To the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive normative study in Singapore or elsewhere has provided normative MoCA scores stratified by discrete combinations of key demographic factors such as age, education, and ethnicity. Furthermore, most existing studies have focused primarily on adjusting for education alone, despite growing evidence suggesting that other variables such as age, ethnicity, lifestyle, and social factors substantially influence cognitive testing scores. To address these gaps, this study applies a regression-based approach to derive stratified normative MoCA scores from a community-based sample representative of Singapore’s multi-ethnic adult population. This approach enables more precise modeling of how cognitive performance varies across demographic subgroups, offering clinicians and researchers contextually relevant benchmarks for initial cognitive screening. Additionally, we investigate the contributions of lifestyle and social factors to MoCA performance to explore their potential relevance for normative interpretation and future research.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Our study sample was drawn from a larger, population-representative health study comprising 1,942 community-dwelling residents aged 21 and above, who were randomly selected from households in central Singapore using a two-step stratified proportional sampling approach. The detailed sampling methodology has been previously described elsewhere36,37. To establish normative data of the cognitively unimpaired general population, we applied several exclusion criteria to the initial sample. We excluded participants who had missing data in MoCA items (n = 77) and reported any physician-diagnosed chronic conditions or psychiatric conditions that could impact cognitive performance, including:

-

Metabolic disorders (diabetes).

-

Cardiovascular conditions (heart attack/failure, stroke/transient ischemic attack).

-

Respiratory diseases (asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease).

-

Psychiatric disorders (depression, anxiety disorder, dementia, schizophrenia).

-

Neurological conditions (Parkinson’s disease).

-

Other chronic conditions (chronic kidney disease, cancer, osteoarthritis/gout/rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis).

To identify undiagnosed depression, we screened participants using the Patient Health Questionnaire and excluded those with depressive symptom scores of 5 or higher. We also excluded participants with visual or auditory difficulties, as well as those with functional impairments identified through the Modified Barthel Index and Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living assessment, as these conditions could directly affect MoCA performance.

Consistent with previous normative studies18,25, we retained participants with hypertension or hyperlipidemia in the sample. This decision avoided creating an unrepresentative “super-normal” sample, given the high prevalence of these conditions in the general population. After excluding participants with incomplete MoCA data and those meeting exclusion criteria, our final normative sample comprised 1,105 “healthy” adults. Figure 1 illustrates the sequential exclusion process.

Measures

Montreal cognitive assessment

The MoCA evaluates global cognitive function across six domains, with total scores ranging from 0 to 30 (higher scores indicating better cognitive function). The seven domains are as follows:

-

Visuospatial / executive function: evaluated using trail making, cube copying and clock drawing tasks.

-

Naming: measured via identifying three animals in the pictures.

-

Short term memory recall: assessed through delayed recall of five words presented earlier.

-

Attention: assessed through digit span tasks (forward and backward), vigilance, and serial subtraction.

-

Language: assessed via sentence repetition and phonemic fluency.

-

Abstraction: evaluated via explaining similarities between two objects or concepts.

-

Orientation: tested through stating the date, month, year, day of the week, place and city.

We administered the validated Singapore version of the MoCA through face-to-face interviews conducted by trained interviewers in each participant’s preferred language. All interviewers completed standardized training and supervised mock assessments conducted in strict accordance with official MoCA administration protocols to ensure inter-rater reliability and consistency in test administration. For Chinese dialect speakers, the Chinese version of the MoCA was used while conducting the assessment in their preferred dialect, as the written text materials remain consistent across all Chinese language variants.

MoCA scores were computed by summing the individual item scores across all cognitive domains, resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 30, where higher scores indicate better cognitive performance. The standard one-point adjustment for education was not applied, as education level was included as an independent variable in the regression models.

Independent variables

Socio-demographic factors were included as independent variables, encompassing age group (21–39, 40–59, 60–74, ≥ 75 years), sex (male, female), education level (no formal education, primary, lower-secondary, secondary, post-secondary & vocational/technical training, bachelor’s degree or higher), employment status (employed full-time, employed part-time, unemployed, homemaker, retired), ethnicity (Chinese, Malay, Indian, others), marital status (single, married, widowed/divorced/separated), living arrangement (living alone, with spouse only, with spouse and children/grandchildren, with children/grandchildren but not spouse, with others), and housing type (public 1–2 room flat, public 3 room flat, public 4–5 room flat or larger, private/ landed property).

Lifestyle factors including the frequency of recreational and social activities (1 = Never to 5 = Very often), smoking status (0 = Never smoked, 1 = Current smoker, 2 = Past smoker), and alcohol misuse (six or more alcoholic drinks on one occasion) as well as social factors, such as social isolation (assessed using the Lubben Social Network Scale-6) and loneliness (measured by the UCLA 3-item scale), were included as covariates for model adjustment.

Statistical analysis

Socio-demographic characteristics of the normative sample, being categorical variables, were summarized using frequencies and percentages.

We used multiple linear regression model (enter method) to assess the associations between individual independent variables and MoCA scores (the dependent variable), computing overall p-values for categorical variables. Although a broader range of variables was initially entered, lifestyle, social and demographic factors including living arrangement, employment status, and housing type were ultimately excluded from the subsequent models due to their limited explanatory power and lack of statistical significance (all p-values > 0.1 except social isolation p = 0.059; see Supplementary Table S1). This stepwise refinement allowed us to retain a model that balanced explanatory power with parsimony, ensuring robustness and practical relevance for generating normative scores. Accordingly, the following four models were developed to systematically assess the impact of various independent variables that were statistically significant. Results are presented as β coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

-

Model 1: Included all identified significant factors including age group, education level, and ethnic group (all p values < 0.05).

-

Model 2: Incorporated continuous age instead of age groups for comparison.

-

Model 3: Collapsed education levels into four categories (no formal education, primary, secondary, and post-secondary or higher) based on: (1) empirical similarity of β coefficients between primary and lower secondary and between post-secondary, vocational/technical training and bachelor’s degree or higher in Model 1; (2) preserved predictive validity with enhanced clinical interpretability; and (3) consistency with prior findings by Ng et al.7.

In Models 1 and 3, individuals aged 21–39 years were selected as the reference group due to their cognitive stability and low prevalence of age-related cognitive decline, providing an appropriate baseline for comparative analysis. We assessed multicollinearity among independent variables using the variance inflation factor, with all values falling below the acceptable cut-off of 2.5. Model assumptions were verified through visual inspection of models’ residual plots and Cook’s distance values to identify potential violations or influential observations. Additionally, we also tested for interaction terms (e.g., age group × education level, age group × ethnicity group), which were not statistically significant (overall p > 0.05) and were excluded to maintain model parsimony. We validated the robustness of the final model (Model 3) via five-fold cross-validation using Stata’s crossfold command.

Normative (predicted mean MoCA scores) and cut-off scores (derived by subtracting 1SD [Root Mean Squared Error in the final equation] from predicted mean MoCA scores) for all demographic combination groups were derived following the methodology outlined by Van Breukelen and Vlaeyen38. By employing regression model coefficients to generate normative scores, this approach facilitated the identification of characteristics relevant to the norming process (validity) and enhanced the continuity and stability of the scores across defined subgroups, thereby improving their reliability38.

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata/SE 17.0 (StataCorp LLC with a two-side alpha level of 0.05 for statistical significance.

Results

The normative sample consisted of 1,105 participants (mean age = 47.3 ± 15.1 years; 56.8% female), with 80.5% being of Chinese ethnicity. Participants aged 40–59 years constituted the largest group (41.8%). Most participants had completed secondary education or higher (74.4%), were employed full-time (64.8%), and married (61.7%). In terms of housing and living arrangement, 55.3% resided in public 4–5 room flats and 42.8% lived with their spouse and children/grandchildren (Table 1).

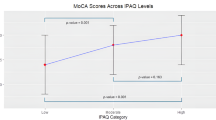

Multiple regression analysis results in Table 2 revealed significant associations between MoCA scores and age, education level and ethnicity (all overall p < 0.001). In Model 1, age demonstrated a negative linear relationship with cognitive performance, with β coefficients ranging from − 0.304 (95% CI: -0.693, 0.084) for those aged 40–59 to -2.278 (95%CI: -0.3220, -1.336) for those aged ≥ 75 compared to the reference group (those aged 21–39). Education level showed strong positive association with MoCA scores, with increasing coefficients from primary education (β = 1.973, 95%CI: 1.210, 2.736) to bachelor’s degree & above (β = 4.390, 95%CI: 3.658, 5.123) relative to no formal education. The minimal differences in β coefficients between (1) primary and lower-secondary education and (2) post-secondary & vocational/technical training and bachelor’s degree or higher groups support collapsing these categories for greater parsimony without substantive loss of information. Ethnic differences were also observed, with Malay (β = -1.168) and Indian participants (β = -0.801) scoring lower than Chinese participants. Overall, Model 1 explained 28.5% of the variance in MoCA scores (adjusted R2 = 0.285).

To explore model parsimony and the relative contribution of variables, alternative specifications were tested. Replacing categorical age groups with a continuous age variable (Model 2) yielded an adjusted R2 of 0.278, suggesting no improvement in model performance. When education level was collapsed into four categories (no formal education, primary, secondary, and post-secondary or higher) rather than the original six categories, the simplified model (Model 3) maintained the similar explanatory power (adjusted R2 = 0.284, Table 2) as Model 1. In this model, all three demographic factors – age group, education level and ethnicity - remained associated with MoCA scores. Age group and education level were the primary contributors to the model (adjusted R2 = 0.271), whereas ethnicity showed a relatively weaker but still statistically significant association with MoCA scores (adjusted R2 = 0.013).

Model 3 was ultimately chosen as the final model for generating normative scores, as it provided comparable explanatory power to Model 1 while using fewer predictors. This increased parsimony enhances interpretability and practical usability, particularly in healthcare settings where simplicity is essential. Furthermore, the reduced number of variables minimizes the risk of overfitting and improves the model’s generalizability across populations.

The MoCA total scores for all existing participants, as well as potential individuals representing combinations of age group, education level and ethnicity with zero observed data in the study, were predicted using the following full linear regression equation:

Together, these findings highlight the importance of applying demographic-specific adjustments when interpreting MoCA scores. Without such adjustments, there is a risk of misclassifying cognitive status in certain groups, particularly older adults and individuals with lower educational attainment or from minority ethnic backgrounds.

Table 3 presents the normative MoCA scores and screening cut-offs stratified by age group, education level, and ethnicity based on the β coefficients derived from Model 3. Consistent patterns emerged across demographic groups. Specifically, MoCA scores decreased with advancing age in all ethnic groups, with the highest scores observed in the 21–39 age group (range: 22.3–27.8) and the lowest in the ≥ 75 age group (range: 20.0-25.5). Educational attainment was positively associated with cognitive performance, with individuals having post-secondary or higher education achieving the highest scores across all age and ethnic groups. Chinese participants generally scored higher than individuals from other ethnic groups within comparable age and education strata. Screening cut-offs, set at one SD (2.648) below the normative scores, were provided for each demographic combination to facilitate clinical interpretation.

Discussion

This study provides normative data for the MoCA in a sample of 1,103 healthy community-dwelling adults in Singapore. The results highlight the significant impact of age, education level, and ethnicity on MoCA scores, offering a more comprehensive understanding of cognitive performance across different demographic groups. Our findings align with existing literature and support the refinement of MoCA scoring systems by accounting for demographic factors that influence cognitive performance.

In our study, age had a strong negative association with MoCA scores, consistent with previous studies showing that cognitive performance typically declines with age19,39. This finding emphasizes the necessity of using age-adjusted normative scores for cognitive screening, particularly for older populations where cognitive decline is more pronounced. The age-related decline in MoCA scores was consistent across all ethnic groups, reinforcing the need for age-stratified screening cut-offs, which can improve the sensitivity of cognitive screening in detecting MCI and early dementia. Although using age as a categorical variable may slightly reduce model precision38, this approach maintained good model fit and enabled the creation of clinically interpretable reference tables.

Educational attainment demonstrated a strong positive association with MoCA scores, with performance gains plateauing at post-secondary or higher levels. The observed score difference - substantial four-point difference between no formal education and post-secondary or higher education and 2.5-point between primary and post-secondary or higher - highlight the substantial impact of education on cognitive performance and support the necessity of education-adjusted scoring protocols. This finding aligns with previous findings that link higher education to greater cognitive reserve7,40,41,42.

Our study revealed modest but significant ethnic differences in cognitive performance, with Malay and Indian participants scoring lower MoCA scores than their Chinese counterparts. This pattern is consistent with previous findings in multi-ethnic populations, locally and internationally, where similar ethnic variations have been documented using MoCA43 or other cognitive screening tools such as the MMSE27,43,44. Notably, these differences persisted even after adjusting for education and other demographic factors, suggesting the potential influence of additional unmeasured factors. These may include occupational complexity, actual literacy levels, linguistic nuances, or cultural differences in test familiarity and cognitive framing45,46,47. Although the MoCA was administered in the participant’s preferred language, subtle language-related differences, particularly in tasks involving verbal fluency or abstract reasoning, may still have affected performance30. Cultural norms surrounding test-taking strategies and cognitive engagement could also contribute to variation in scores across ethnic groups48. While our study did not directly assess these factors, future research could explore how cultural and linguistic context, along with broader socioeconomic indicators, may shape cognitive test outcomes in multi-ethnic populations.

Importantly, we found no interaction between education and ethnicity, which contrasting with previous MMSE findings27. By including participants from all the major ethnic groups in Singapore, our study extends previous work which included only Chinese participants7 and provides normative data that are more representative of the nation’s diverse population, enhancing the generalizability and equity of cognitive assessment within Singapore’s multicultural context.

Our use of regression modeling addresses key limitations of previous studies that relied on conventional subgroup analysis. By retaining a larger sample size, our approach yields more stable and generalizable estimates, while empirically identifying the demographic factors that significantly influence MoCA performance. This regression-based norming has gained considerable popularity due to its flexibility, which allows for the development of more individualized and potentially realistic normative scores. Additionally, it offers greater efficiency, often requiring smaller sample sizes to achieve comparable levels of precision to traditional norming methods49. The normative scores generated from our final model, stratified by age, education, and ethnicity groups, with cut-offs defined at one standard deviation below predicted mean scores, offer a more refined and inclusive identification of cognitive impairment across diverse population subgroups, particularly in multi-ethnic settings like Singapore. These scores enable clinicians to more appropriately interpretate MoCA results based on an individual’s demographic background, thereby enhancing the accuracy of cognitive screening. This supports earlier and more accurate identification of cognitive decline and promotes timely intervention in routine clinical practice.

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design prevents conclusions about cognitive decline progression or the predictive validity of the normative scores. Longitudinal studies are needed to assess the utility of these scores in detecting early cognitive changes and predicting the onset of MCI and dementia in settings such as annual cognitive screening for older adults, ongoing monitoring of individuals with subjective cognitive concerns, or at-risk populations with comorbidities like hypertension or diabetes. Such scenarios would allow researchers and clinicians to assess whether individuals classified below normative thresholds are more likely to experience cognitive decline over time, thereby strengthening the clinical relevance and predictive accuracy of the proposed norms. Second, despite sample diversity, Chinese participants predominated, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Future studies with larger and more ethnically diverse samples—including deliberate oversampling of underrepresented groups such as Malay and Indian participants—would be beneficial for refining and validating these normative scores. This would ensure greater representativeness and support more equitable application of cognitive screening tools in multi-ethnic populations.

Third, while we controlled for multiple demographic and health factors, residual confounding may persist due to: (1) undiagnosed cognitive impairment in our ostensibly healthy sample, which could attenuate normative score accuracy; (2) undiagnosed chronic health conditions - such as diabetes or hypertension - that are prevalent and known to influence cognitive performance50; (3) unmeasured biological or environmental factors influencing cognitive performance; and (4) potential interactions between controlled variables that were not modelled. These factors may collectively impact on the predictive precision of our models.

Lastly, it is also important to note the potential risk of misclassification, particularly within subgroups without observation data or with smaller sample sizes—such as Indian individuals aged 75 and older and individuals of other ethnicities aged 60–74—where wider score variability may reduce the stability and generalizability of the reference scores derived. Generating valid and stable normative reference scores typically requires adequately powered samples, and subgroup analyses based on insufficient data may mislead clinical interpretation. This limitation should be carefully considered when applying the scores in clinical practice and highlights the need for cautious interpretation in underrepresented groups. Future studies should prioritize oversampling these subgroups to the development of more robust, age-specific reference values for these populations.

Future research should seek to validate the proposed demographic-specific screening reference scores against clinically diagnosed cohorts of MCI and dementia. Such validation is essential for evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of these reference scores for determining their appropriateness in identifying individuals at risk of cognitive impairment. This step would also help refine stratified cut-offs to improve the accuracy of cognitive screening across diverse populations. In addition, transforming raw MoCA scores into percentiles may support a more comprehensive approach to evaluating neurocognitive performance, facilitating assessment, diagnosis, and rehabilitation planning51.

The primary aim of this study was to establish normative data based on the total MoCA score, which remains the most widely validated and clinically practical index for global cognitive screening. Accordingly, our analysis focused on total score performance. Nonetheless, we acknowledge the potential value of MoCA subdomain scores (e.g., memory, executive function) in identifying domain-specific cognitive deficits. Future studies should explore whether integrating subdomain profiles with total scores improves screening accuracy for specific neurodegenerative conditions. Such efforts would enhance the MoCA’s clinical interpretability and address current limitations of brief subdomain measures.

It is also important to note that different versions of the MoCA were used in this study, including English, Chinese, and Malay adaptations. While these versions were designed to accommodate language and cultural differences, subtle variations in item phrasing, cultural relevance, or linguistic complexity may have influenced participant performance. These version-specific differences may partially confound observed ethnic differences in MoCA scores and should be considered when interpreting findings. Future studies should explore the impact of language version on test performance more systematically.

Implications for clinical practice

This study offers demographically stratified normative MoCA scores across age, education, and ethnicity groups in Singapore’s adult population. These reference scores have practical utility in supporting clinicians during the early stages of cognitive screening by allowing more demographically appropriate comparisons. In particular, demographic-specific norms may help mitigate under- or over-identification of cognitive impairment in populations that have historically been underrepresented in normative datasets—such as ethnic minorities or individuals with lower educational attainment.

In clinical practice, these norms can assist in contextualizing a patient’s MoCA score relative to peers with similar sociodemographic characteristics. For example, if an individual scores more than one standard deviation below their subgroup mean, this may prompt clinicians to consider further neuropsychological testing or diagnostic referral. These findings could therefore help streamline triaging decisions, enable earlier identification of at-risk individuals, and reduce false positives or negatives stemming from uniform cut-offs.

However, it is important to emphasize that these reference scores are not diagnostic cut-offs. They should be interpreted as descriptive tools to guide—but not replace—clinical decision-making. Especially in subgroups with smaller sample sizes and greater variability (e.g., Malay participants aged ≥ 75), caution is warranted. Future research should validate these screening reference scores in clinically diagnosed cohorts to strengthen their application in real-world diagnostic workflows.

Moreover, given that participants completed different language versions of the MoCA (English, Chinese, and Malay), clinicians should be mindful that linguistic and cultural modifications may influence test performance. These factors may affect comparability across ethnic groups and should be considered when interpreting low scores, particularly in multilingual, multicultural settings like Singapore.

Conclusions

This study establishes baseline MoCA performance patterns across demographic groups in Singapore’s multi-ethnic population. The findings underscore the influence of age, education, and ethnicity on cognitive screening outcomes, offering important context for clinical interpretation. The resulting stratified reference scores provide clinicians and researchers with a practical framework for comparing individual MoCA performance against demographically similar peers. While these demographic-specific reference scores may help identify individuals warrant further cognitive evaluation, they should be used cautiously and in conjunction with other clinical information, rather than as standalone diagnostic criteria.

Data availability

According to the Data Protection Act Commission Singapore -Advisory Guidelines for the Healthcare Sector, the personal health data collected for the Population Health Index study are not publicly available due to legal and ethical restrictions related to data privacy protection. However, the minimal dataset underlying the findings in the manuscript are available upon request to interested researchers after authorization of the institutional ethical committee. Interested researchers may contact Dr Chun Wei Yap (Chun_Wei_Yap@nhg.com.sg) for data requests.

References

Subramaniam, M. et al. Prevalence of dementia in people aged 60 years and above: results from the wise study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD. 45, 1127–1138 (2015).

Abdin, E. et al. The societal cost of dementia in Singapore: results from the wise study. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD. 51, 439–449 (2016).

National Population and Talent Division, Stratey Group. Prime Minister’s Office. Population in Brief 2024. (2024). https://www.strategygroup.gov.sg/files/media-centre/publications/Population_in_Brief_2024.pdf

Farias, S. T., Mungas, D., Reed, B. R., Harvey, D. & DeCarli, C. Progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia in clinic-vs community-based cohorts. Arch. Neurol. 66, 1151–1157 (2009).

Nasreddine, Z. S. et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 53, 695–699 (2005).

Dong, Y. et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment is superior to the Mini–Mental state examination in detecting patients at higher risk of dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 24, 1749–1755 (2012).

Ng, T. P. et al. Montreal cognitive assessment for screening mild cognitive impairment: variations in test performance and scores by education in Singapore. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 39, 176–185 (2015).

Aggarwal, A. & Kean, E. Comparison of the folstein Mini mental state examination (MMSE) to the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) as a cognitive screening tool in an inpatient rehabilitation setting. Neurosci. Med. 1, 39–42 (2010).

Alagiakrishnan, K., Zhao, N., Mereu, L., Senior, P. & Senthilselvan, A. Montreal Cognitive Assessment is superior to Standardized Mini-Mental Status Exam in detecting mild cognitive impairment in the middle-aged and elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. BioMed Res. Int. 186106 (2013). (2013).

Dong, Y. et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) is superior to the Mini-Mental state examination (MMSE) for the detection of vascular cognitive impairment after acute stroke. J. Neurol. Sci. 299, 15–18 (2010).

Hoops, S. et al. Validity of the MoCA and MMSE in the detection of MCI and dementia in Parkinson disease. Neurology 73, 1738–1745 (2009).

Jia, X. et al. A comparison of the Mini-Mental state examination (MMSE) with the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) for mild cognitive impairment screening in Chinese middle-aged and older population: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 21, 485 (2021).

Pendlebury, S. T., Cuthbertson, F. C., Welch, S. J. V., Mehta, Z. & Rothwell, P. M. Underestimation of cognitive impairment by Mini-Mental state examination versus the Montreal cognitive assessment in patients with transient ischemic attack and stroke. Stroke 41, 1290–1293 (2010).

Zadikoff, C. et al. A comparison of the mini mental state exam to the Montreal cognitive assessment in identifying cognitive deficits in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 23, 297–299 (2008).

Freitas, S., Simões, M. R., Martins, C., Vilar, M. & Santana, I. Estudos de Adaptação do Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) Para a população Portuguesa. Aval Psicológica. 9, 345–357 (2010).

Fujiwara, Y. et al. Brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment in older Japanese: validation of the Japanese version of the Montreal cognitive assessment. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 10, 225–232 (2010).

Liew, T. M., Feng, L., Gao, Q., Ng, T. P. & Yap, P. Diagnostic utility of Montreal cognitive assessment in the fifth edition of diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: major and mild neurocognitive disorders. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 16, 144–148 (2015).

Conti, S., Bonazzi, S., Laiacona, M., Masina, M. & Coralli, M. V. Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA)-Italian version: regression based norms and equivalent scores. Neurol. Sci. Off J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol. 36, 209–214 (2015).

Freitas, S., Simões, M. R., Alves, L. & Santana, I. Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA): normative study for the Portuguese population. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 33, 989–996 (2011).

Freitas, S., Simoes, M. R., Alves, L. & Santana, I. Montreal cognitive assessment: influence of sociodemographic and health variables. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 27, 165–175 (2012).

Kenny, R. A. et al. Normative values of cognitive and physical function in older adults: findings from the Irish longitudinal study on ageing. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 61, 279–290 (2013).

Larouche, E. et al. Normative data for the Montreal cognitive assessment in Middle-Aged and elderly Quebec-French people. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 31, 819–826 (2016).

Lee, Y. J. et al. Factors associated for mild cognitive impairment in older Korean adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. J. 38, 150–157 (2014).

Narazaki, K. et al. Normative data for the Montreal cognitive assessment in a Japanese Community-Dwelling older population. Neuroepidemiology 40, 23–29 (2013).

Santangelo, G. et al. Normative data for the Montreal cognitive assessment in an Italian population sample. Neurol. Sci. 36, 585–591 (2015).

Tan, J. et al. Optimal cutoff scores for dementia and mild cognitive impairment of the Montreal cognitive assessment among elderly and oldest-old Chinese population. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD. 43, 1403–1412 (2015).

Ng, T. P., Niti, M., Chiam, P. C. & Kua, E. H. Ethnic and educational differences in cognitive test performance on Mini-Mental state examination in Asians. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 15, 130–139 (2007).

Asmuje, N. F., Mat, S., Myint, P. K. & Tan, M. P. Ethnic-Specific sociodemographic factors as determinants of cognitive performance: Cross-Sectional analysis of the Malaysian elders longitudinal research study. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 51, 396–404 (2022).

Delerue Matos, A., Barbosa, F., Cunha, C., Voss, G. & Correia, F. Social isolation, physical inactivity and inadequate diet among European middle-aged and older adults. BMC Public. Health. 21, 924 (2021).

Luo, M. & Li, L. Social isolation trajectories in midlife and later-life: patterns and associations with health. Int J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 37, (2022).

Adherence to a healthy. Lifestyle and its association with cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults in Shanghai. Front. Public. Health. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1291458 (2023).

Huang, Z. et al. Associations of lifestyle factors with cognition in Community-Dwelling adults aged 50 and older: A longitudinal cohort study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 601487 (2020).

Lifestyle factors that. Affect cognitive function–a longitudinal objective analysis. Front Public. Health 11, (2023).

Ng, A., Chew, I., Narasimhalu, K. & Kandiah, N. Effectiveness of Montreal cognitive assessment for the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s disease in Singapore. Singap. Med. J. 54, 616–619 (2013).

Gagnon, G. et al. Correcting the MoCA for education: effect on sensitivity. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 40, 678–683 (2013).

Ge, L., Yap, C. W., Ong, R. & Heng, B. H. Social isolation, loneliness and their relationships with depressive symptoms: A population-based study. PLOS ONE. 12, e0182145 (2017).

Yap, C. W., Ge, L., Ong, R., Li, R. & Heng, B. H. Development of a scalable and extendable multi-dimensional health index to measure the health of individuals. PLOS ONE. 15, e0240302 (2020).

Breukelen, G. J. P. & Vlaeyen, J. W. S. Norming clinical questionnaires with multiple regression: the pain cognition list. Psychol. Assess. 17, 336–344 (2005).

Nasreddine, Z. S. et al. Normative data for the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) in a population-based sample. Neurology 78, 765–766 (2012).

Apolinario, D. et al. Normative data for the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) and the memory index score (MoCA-MIS) in Brazil: adjusting the nonlinear effects of education with fractional polynomials. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 33, 893–899 (2018).

Hayek, M., Tarabey, L., Abou-Mrad, T., Fadel, P. & Abou-Mrad, F. Normative data for the Montreal cognitive assessment in a Lebanese older adult population. J. Clin. Neurosci. Off J. Neurosurg. Soc. Australas. 74, 81–86 (2020).

Impacts of education level on Montreal Cognitive. Assessment and saccades in community residents from Western China. Clin. Neurophysiol. 161, 27–39 (2024).

Wong, L. C. K. et al. Interethnic differences in neuroimaging markers and cognition in Asians, a population-based study. Sci. Rep. 10, 2655 (2020).

Rossetti, H. C., Lacritz, L. H., Cullum, C. M. & Weiner, M. F. Normative data for the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) in a population-based sample. Neurology 77, 1272–1275 (2011).

Culture and Cognitive Testing. SciSpace - Paper 135–159 https://scispace.com/papers/culture-and-cognitive-testing-3otsgn6ubz (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6887-4_7

Screening for cognitive. Impairment among older people in black and minority ethnic groups. Age Ageing. 33, 447–452 (2004).

The influences of linguistic demand and cultural loading on Cognitive Test Scores. J. Psychoeduc Assess. 32, 610–623 (2014).

Cultural Effects on the Performance of Older Haitian. Immigrants on timed cognitive tests. Med Res. Arch 12, (2024).

Timmerman, M. E., Voncken, L. & Albers, C. J. A tutorial on regression-based norming of psychological tests with GAMLSS. Psychol. Methods. 26, 357–373 (2021).

de Oliveira, M. F. B., Yassuda, M. S., Aprahamian, I., Neri, A. L. & Guariento, M. E. Hypertension, diabetes and obesity are associated with lower cognitive performance in community-dwelling elderly: data from the FIBRA study. Dement. Neuropsychol. 11, 398–405 (2017).

Gaete, M. et al. Standardised results of the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) for neurocognitive screening in a Chilean population. Neurol. Engl. Ed. 38, 246–255 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Healthcare Group in the form of salaries for all authors. The funder had no role in the design, data collection, data analysis, and reporting of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RO, LG, and CWY conceptualized and designed the study; LG and RO analyzed and interpreted the data, prepared the tables, and drafted the manuscript. LG critically revised the manuscript. CWY supervised the PHI study, verified data analyses and result interpretation. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The PHI study was reviewed and approved by the ethics review committee of the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (Reference Number: 2015/00269). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants after they were informed about the study objectives and the safeguards put in place so that confidentiality of the collected data is maintained.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ong, R., Yap, C.W. & Ge, L. Regression-based normative scores for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in an Asian population. Sci Rep 15, 17895 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03167-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03167-5