Abstract

Malaria is a major public health problem, with nearly half of the world’s population at risk. In Ethiopia, despite prevention efforts, malaria continues to be a significant issue, particularly in the post-war Tigray region. Insecticide-treated net (ITN) is a key preventive tool, but data on its distribution and usage in this region are limited. A community-based, cross-sectional study was conducted from January to February 2024 across 24 randomly selected districts, involving 2,338 households. Data were collected using Open Data Kit and analyzed with SPSS version 21, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05. The findings revealed that 58.1% (95% CI 56.1–59.9) of households owned at least one ITN, and 61.6% (95% CI 59.1–64.2) reported using it the previous night. Multivariable logistic regression identified that being single was associated with lower ITN use (AOR = 0.5; 95% CI 0.3–0.7), while households with 3–4 members (AOR = 1.8; 95% CI 1.2–2.6) and those with sufficient ITNs (AOR = 1.4; 95% CI 1.1–1.8) had higher usage rates. These findings highlight the need for tailored malaria prevention strategies, including sustained ITN distribution, ongoing health education, and targeted interventions to improve ITN utilization, to contribute to malaria elimination and achieve universal health coverage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria is a preventable and treatable disease that continues to have a dire impact on people’s health, and nearly 50% of the world’s population is at risk1,2. It causes unacceptably high morbidity and mortality, including cerebral malaria, severe anemia, and respiratory distress. In 2020, global malaria cases reached around 241 million, 627 thousand deaths, and in 2023 it has increased by around 11 million cases1,3,4. An estimated 249 million malaria cases have been documented in 85 malaria endemic countries in 2022. Ninety-four percent of these cases and 95% of all malaria deaths occur in Africa, and the continent has faced threats to eliminate it by 20303,5,6.

Infants, children under 5 years, pregnant women, and People Living with Human Immune Deficiency Virus (PLWHIV) are at higher risk of severe infection. Children under five years of age suffer with around 80% of all malaria deaths, and severe forms of malaria is terrible to every home in Africa7,8,9. Long-Lasting Insecticidal Treated Net (LLIN) is cost-effective and one of the three strategic pillars (ensure universal access to malaria prevention, diagnosis and treatment; accelerate efforts towards elimination and attainment of malaria-free status; and transform malaria surveillance into a core intervention) of Global Technical Strategy (GTS) to significantly reduce morbidity and mortality due to malaria10,11.

Ethiopian national health policy provides attention to prevention and control of communicable diseases, including malaria. To ensure universal access to Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs) and prevent malaria, one ITN for every two persons in a household is recommended12,13. Consequently, Ethiopia has been distributed ITNs free of charge to the community. Despite dramatic improvements in prevention, diagnosis and treatment of malaria cases in the last two decades, around 69% of Ethiopians are still at risk of malaria13,14.

Tigray, one of the regions found in the northern part of Ethiopia has faced a disastrous armed conflict since November 2020, and the health system has collapsed15,16. In October 2022, malaria had increased by 80% compared to the previous year and was documented to be the highest cause of morbidity in the region17. Moreover, Tigray was under complete siege and blockade; maternal mortality ratio reached around 840 per 100,000 live births during the wartime18. Therefore, the study was conducted to assess the status of ITNs ownership and utilization in Tigray, northern Ethiopia.

Methods and materials

Study setting and period

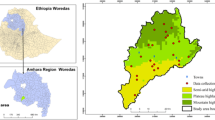

The study was conducted in six zones of Tigray regional state, northern Ethiopia. Western zone and some areas were not included for security reasons. Tigray is bordered by Afar in the east, Amhara in the south, Eritrea in the north, and Sudan in the west. The elevation of Tigray ranges from 600 to 2700 m above sea level, with annual rainfall ranging from 450 to 980 mm19. It is one of the highest malaria affected regions in Ethiopia. Tigray is administratively divided into seven zones and 93 districts, with only 78 accessible districts during the study period. The data were collected from January to February 2024 in 24 randomly selected districts.

Study design

The study employed a community based cross-sectional study design among randomly selected households.

Study population

All households except western zone and inaccessible households of Tigray were the source population, and randomly selected households were the study population.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All randomly selected households were included in the study; the western zone of Tigray and households that were not accessible during the study period were excluded for security reasons.

Sample size determination, sampling technique and procedure

A multi-stage clustered sampling technique was employed to recruit a total of 2340 households. In the first stage, six zones except the western Tigray were included. From the six zones, a representative of 30% districts (n = 24) with 78 Tabias (the lowest administrative unit) were included randomly. Finally, 30 households from each Tabia using systematic sampling techniques were surveyed. Urban to rural ratio of districts (16 rural versus 8 urban) and households were also considered, with 70% rural and 30% urban, i.e. 78 Tabia*30 = 2340 households20. As shown in Fig. 1.

Variables and operational definition

Dependent variable Insecticide-treated net ownership and utilization were the dependent variables.

Independent variables Were categorized in to sociodemographic characteristics (marital status, age, religion, ethnicity, educational status, residence, participant type, availability of TV/radio and family size), and vector prevention and control related variables (perceived presence of mosquito, knowledge on preventive mechanisms of malaria, health education provision, adequacy of ITNs, perceived malaria attack and community engagement practices).

ITNs ownership Was determined by the response provided through the interviewer-administered question “yes” for household that had at least one ITNs and “No” for households which didn’t have at least one ITNs; coded “1” and “0”, respectively.

Utilization ITNs utilization was measured as the proportion of a given population group that slept with an ITN the night before the survey who had at least one ITN in their household.

Adequacy Refers to the availability of one ITNs per two persons in the household.

Data collection methods

The questionnaire was designed to collect information on sociodemographic characteristics of the household, net ownership, family size, educational status, age, residence, listening to radio/television, presence of vectors around their households, vector prevention and control related questions, health-seeking behavior related, number of ITNs, participation in environmental management towards mosquito prevention, seeking treatment for malaria, and ITNs utilization. Data were collected using an interviewer-administered questionnaire. The study employed 13 B.Sc. degree holders as data collectors and 6 masters’ degree supervisors.

To ensure consistency and improve the accuracy of the data collection instruments, the questionnaire was first prepared in English, translated into Tigrigna, and then translated back into English. Intensive training was given for five days to supervisors and data collectors on the objectives of the study and data collection techniques in order to ensure the uniformity and clarity of the questionnaire. The questionnaire was pretested at Adigrat to estimate the time required and to make adjustments needed before the actual survey began. Randomly selected household mothers or any member of the household over 18 years who could provide credible information were interviewed. Moreover, the data were collected with the Open Data Kit (ODK), monitored from the center, and followed on the spot for consistency and completeness.

Data analysis

Data were exported to SPSS version 21, cleaned, coded and checked for consistency. Descriptive statistical analysis was undertaken and expressed in frequency and proportion. Cross-tabulation was performed to determine the distribution of the independent variables in relation to the dependent variable. Marital status, age, residence, TV/radio availability, educational status, family size, health education provision, adequacy of ITNs and perceived malaria attack within the family entered into bivariate logistic regression to examine the association between the independent and the dependent variable (ITNs utilization). Variables with P ≤ 0.25 at the bivariate regression were exported to the multivariable logistic regression model to control confounding factors and to determine the independent predictor of ITNs utilization. Model fitness was checked using Hosmer and Lemeshow test (P = 0.326), which is greater than 0.05. An Odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval was used to measure the strength of the association. Statistical significance was determined with P < 0.05.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

A total of 2338 study participants with a 99.9% response rate were included in the study. The mean age (± SD) of the study participants was 28.7 ± 6.2 years. Most of the participants were married (89.4%) and almost three-fourths (72.6%) of them were rural residents. Nearly half (50.2%) of the respondents were in the age range of 25–34 years with a median of five, and approximately 42% of the households had 3–4 family sizes as shown in Table 1.

Knowledge and community practice on vector prevention and control measures

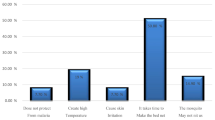

Approximately 63.6% (95% CI 61.5–65.5) of the study participants perceived the existence of mosquitoes around their household. Nearly eighty-eight percent (87.9%) of study participants knew that environmental management was a mosquito bite preventive mechanism. Besides, community practice on vector prevention and control activities were conducted, as shown in (Table 2).

ITNs ownership

Out of the 2338 households assessed, 58.1% (95% CI 56.1–59.9) of them had at least a single ITNs with a mean score of 1.4. Approximately one-third and 0.3% of the surveyed households had one and five ITNs, respectively. In the surveyed households, a total of 11,960 people live and own a total of, 2728 ITNs. Out of these households that possessed ITNs, approximately 42% of them had adequate ITNs as shown in (Fig. 2).

Health seeking behavior

Of the surveyed households’, 905 (38.7%) reported malaria-attack has been occurred among their family members six months prior to data collection, and 64.1% of them sought treatment. Some of the reasons mentioned for not seeking treatment were lack of drugs in the health facilities, physical inaccessibility of health facilities, absence of healthcare providers in the health facilities, and cost of drugs in private clinics. In addition, some respondents mentioned that they used drugs borrowed from peers or neighborhoods, as shown in (Table 3).

ITNs utilization and associated factors

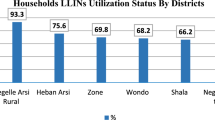

As the analysis of ITNs use was on households that had access to ITNs, households without any ITNs were excluded from the analysis and left 1358. The prevalence of ITNs utilization in the households that owned at least one ITNs (837/1358) was 61.6% (95%Cl, 59.1–64.2). Furthermore, potential determinant factors for ITNs utilization were explored, and being single (AOR = 0.5, 95% CI 0.3–0.7), family size (AOR = 1.8, 95% CI 1.2–2.6) and adequacy of ITNs (AOR = 1.4, 95% CI 1.1–1.8) were significantly associated with utilization of ITNs, as shown below in (Table 4).

Discussion

Ethiopia envisioned being a malaria-free country by 2030 through the adoption of appropriate malaria prevention and control strategies. Among these strategies, vector control is a vital component, as it is highly effective in preventing infection and reducing disease transmissions12,21. ITNs is cost-effective, pivotal to halting the transmission of malaria, and play a vital role in the achievement of Universal Health Coverage (UHC)11.

The ownership of at least one ITNs in the surveyed households was found to be 58.1% (95% CI 56.1–59.9). This finding was consistent with studies conducted in Southwest Ethiopia (56.6%)22, and Harari (57.9%)23, but lower compared to studies conducted in Afar (86.1%)24, and SNNPR (67.5%)25. The discrepancy might be explained due to sociodemographic variation, study population, study design, political instability and access to healthcare14,16,17.

Furthermore, the current study found that one ITNs is distributed per every five persons, which is lower compared to the national plan aiming at covering 100% of the population at risk of malaria12,13,26.

The proportion of households utilizing ITNs was 61.6% (95% CI 59.1–64.2). This result aligns with surveys conducted in Gojam (59.1%)27 and Uganda (56.8%)28. However, it is lower than findings from Gonder (91.9%)29 and Oromia (72.2%)30, yet higher than results from Ghana (41.7%)31. This variation may result from differences in ITN accessibility, perceptions of malaria transmission, characteristics of the study population, cultural norms, environmental factors, and sociodemographic aspects of the participants. Additionally, research suggests that conflict poses significant challenges to the effective implementation of healthcare services, including malaria control efforts, and the Tigray region had been experiencing intense conflict, under a full siege and blockade3,32. Furthermore, the difference might be explained by the varying operational definitions of ITN utilization. Most prior studies defined proper utilization of ITNs as “households possessing ITNs with one or more members sleeping under a net,” which was verified through enumerators’ observation. However, the current study assessed the use of ITNs by relying on respondents’ self-reports. Another possible reason for the differences in findings could be the variance in study populations; most previous research on ITN usage has concentrated on high-risk demographics such as pregnant women, school-age children, and children under five, while this study included all individuals residing in the study area.

Malaria transmission in Ethiopia is characterized by its high seasonality and instability, exacerbated by factors such as poverty, humanitarian crises, drought, food scarcity, climate change, population movements, and ongoing conflicts that can lead to significant outbreaks of the diseases which could result in unprecedented surge of epidemic malaria2,17,33,34,35. Research has also indicated that malaria transmission can occur during the dry seasons in Ethiopia36,37, underscoring consistent use of malaria prevention strategies is vital to stay protected from the disease.

Among the various factors investigated, respondents who identified as single were 50% less likely to use ITNs than those who were married. This may be attributed to the notion that when ITNs are in limited supply, usage may be influenced by the priority assigned to families with children, access to healthcare services, and the greater responsibility that married women often have towards the health of their families. Additionally, study participants who had sufficient ITNs were 1.4 times more inclined to use them compared to those without adequate access. Furthermore, households consisting of 3–4 members were 1.8 times more likely to use ITNs than those with 7 or more members, which aligns with findings from a study conducted in Ethiopia38. Likewise, evidence has shown that inadequate distribution of ITNs is a significant barrier to their usage39. Furthermore, the findings should be interpreted thoroughly. First, ITNs utilization was assessed based on the respondents self-report. Consequently, social desirability and recall bias could be introduced. Second, the study was cross-sectional and it didn’t show temporal relationship. Additionally, we didn’t assess any miscellaneous usage or the misuse of ITNs in this study.

Conclusions

Overall, ITNs ownership and utilization were low compared to the national plan. Efforts to eliminate malaria could be a challenge to achieve the UHC and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Therefore, it is recommended that distribution, continuous healthcare awareness creation and use of ITNs for malaria prevention and elimination should be strengthened.

Data availability

Data supporting the results of the study are available in the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ITNs:

-

Insecticidal treated nets

- COR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- SDG:

-

Sustainable development goals

- UHC:

-

Universal health coverage

- HHs:

-

Households

References

Longley, R. J. et al. MAM 2024: Malaria in a changing world. Trends Parasitol. 40(5), 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2024.03.007 (2024).

Kolawole, E. O. et al. Malaria endemicity in sub-Saharan Africa: Past and present issues in public health. Microbes Infect. Dis. 4(1), 242–251 (2023).

Venkatesan, P. The 2023 WHO world malaria report. Lancet Microbe 5(3), e214. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-5247(24)00016-8 (2024).

Venkatesan, P. WHO world malaria report 2024. Lancet Microbe 6(4), 101073 (2025).

Tavares, J., Cordeiro-Da-Silva, A. & Calderón, F. Ending malaria: Where are we? ACS Infect. Dis., 1429–1430 (2024).

AU-ALMA. AU Malaria Progress Report 2023 (2023).

Mirzohreh, S. T. et al. Malaria prevalence in HIV-positive children, pregnant women, and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasites Vectors 15(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05432-2 (2022).

Release P. Africa-Europe partnership launches study to evaluate emergency response tools for severe malaria in highly isolated rural settings (2023).

WHO. World malaria report (2019). https://www.mmv.org/newsroom/news-resources-search/world-malaria-report-2019

Stebbins, R. C., Emch, M. & Meshnick, S. R. The effectiveness of community bed net use on malaria parasitemia among children less than 5 years old in Liberia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 98(3), 660 (2018).

Malaria Consortium. Malaria prevention through insecticide treated nets, 1–5. https://www.malariaconsortium.org/media-downloads/802/Malaria prevention through insecticide treated nets (2016).

Malaria Policy Advisory Committee Meeting. Universal access to core malaria interventions in high-burden countries (2018).

Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health. National Malaria Guidelines. FMoH (2022).

FMoH. National malaria elimination strategic plan (2024/25–2026/27). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (2023).

Plaut, M. The International community struggles to address the Ethiopian conflict. RUSI Newsbrief RUSI (2021).

Gesesew, H. et al. The impact of war on the health system of the Tigray region in Ethiopia: An assessment. BMJ Glob. Heal. 6(11), e007328 (2021).

WHO. Malaria surging in Tigray. Geneva; 2022; https://medicalxpress.com/news/2022-10-malaria-surging-tigray.html

Legesse, A. Y. et al. Maternal mortality during war time in Tigray, Ethiopia: A community-based study. BJOG An. Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 131(6), 786–794 (2024).

Tekulu, F. B. Urbanization level and tempo (speed) in Tigray Regional State, Ethiopia. Res Sq. 1–9 (2023).

Bennett, S. & Iiyanagec, W. M. 15; simplified general method for cluster-sample surveys ofHealth in developing countries (1988)

FMoH. Ethiopia Malaria Profile. CdC, 2(Fy 2022), 1–20 (2022).

Sena, L. D., Deressa, W. A. & Ali, A. A. Predictors of long-lasting insecticide-treated bed net ownership and utilization: Evidence from community-based cross-sectional comparative study, Southwest Ethiopia. 1–9 (2013).

Teklemariam, Z., Awoke, A., Dessie, Y. & Weldegebreal, F. Ownership and utilization of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) for malaria control in Harari National Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 21, 1–9 (2015).

Negash, K., Haileselassie, B., Tasew, A., Ahmed, Y. & Getachew, M. Ownership and utilization of long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets in Afar, northeast Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. 13(Supp 1), 1–5 (2012).

Batisso, E. et al. A stitch in time: A cross-sectional survey looking at long lasting insecticide-treated bed net ownership, utilization and attrition. 1–7.

World Health Organization. Global technical strategy for malaria 2016–2030. WHO 135 (2016). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream

Woreda, D., Zone, E. G., Kassie, A., Wale, M. & Fekensa, T. Assessment of insecticide treated bed net possession, proper utilization and the prevalence of malaria. 5(7), 92–103 (2014).

Akello, A. R., Byagamy, J. P., Etajak, S., Okadhi, C. S. & Yeka, A. Factors influencing consistent use of bed nets for the control of malaria among children under 5 years in Soroti District, North Eastern Uganda. Malar. J. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-022 (2022).

Alemu, M. B., Asnake, M. A., Lemma, M. Y., Melak, M. F. & Yenit, M. K. Utilization of insecticide treated bed net and associated factors among households of Kola Diba town, North Gondar, Amhara region, Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 11(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3697-7 (2018).

Mekuria, M. et al. Insecticide-treated bed net utilization and associated factors among households in Ilu Galan District, Oromia (2022).

Konlan, K. D. et al. Utilization of insecticide treated bed nets (ITNs) among caregivers of children under five years in the Ho Municipality. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. (2019).

Weldemichel, T. G. Inventing hell: How the Ethiopian and Eritrean regimes produced famine in Tigray. Hum. Geogr. 15(3), 290–294 (2022).

FMoH. Ethiopia malaria profile. 2:1–20 (2022).

Haile, M., Lemma, H. & Weldu, Y. Population movement as a risk factor for malaria infection in high-altitude villages of Tahtay-Maychew District, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: A case-control study. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 97(3), 726–732 (2017).

Gonahasa, S. et al. LLIN evaluation in Uganda project (LLINEUP): Factors associated with ownership and use of long-lasting insecticidal nets in Uganda—A cross-sectional survey of 48 districts ISRCTN17516395 ISRCTN. Malar. J. 17(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-018-2571-3 (2018).

Amare, A., Eshetu, T. & Lemma, W. Dry-season transmission and determinants of Plasmodium infections in Jawi district, Northwest Ethiopia. Malar. J. 21(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-022-04068-y (2022).

Tefera, S., Bekele, T. & Ketema, T. Effect of seasonal variability on the increased malaria positivity rate in drought—prone malaria endemic areas of Ethiopia. J. Parasit. Dis. 48(4), 860–871. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12639-024-01720-z (2024).

Policy H. Insecticide-treated net ownership and utilization and factors that influence their use in Itang, Gambella region, Ethiopia: Cross-sectional study. 101–112 (2016).

Linn, S. Y. et al. Barriers in distribution, ownership and utilization of insecticide-treated mosquito nets among migrant population in Myanmar, 2016: A mixed methods study. Malar. J. 18(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-019-2800-4 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Tigray Health Bureau, study participants, data collectors, supervisors, district health office, and local administrators for their cooperation during the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GBG: conceptualization, drafting the manuscript, supervision, analysis, investigation, editing and data curation. HDH, HGW and MHT: conceptualization, drafting the manuscript, supervision and analysis. TB, GHR, MME, GGM, AKB, YBT, and MGB: Supervision, analysis, editing and data curation. GGG, HG, MGW, WGH and AGG: Drafting manuscript, supervision, investigation and editing. MHG, RE, AAA and MT: Conceptualization, supervision, investigation, editing and data curation. Finally, all authors gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was carried out according to Helsinki Ethical Declaration. Administrative approval was obtained from Tigray Health Bureau and respective districts. Ethical approval for the study was secured from the Institutional Review Board of Tigray Health Research Institute (THRI) with Ref. No. THRI/4031/0503/16. All participants provide informed consent before participating in the study and their anonymity, privacy and confidentiality were respected. Oral consent was appropriate and acceptable for the context and approved by the relevant ethics committee of the THRI.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gebrekidan, G.B., Hidru, H.D., Woldearegay, H.G. et al. The status of ownership and utilization of long-lasting insecticidal treated nets in war-torn Tigray, Ethiopia. Sci Rep 15, 27847 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03180-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03180-8