Abstract

Light is increasingly being used to drive soft robots and soft actuators. In this paper, a light-driven soft robot with compound motion patterns based on gas-liquid phase transition chamber is proposed, which inspired by the frog and the larvae of gall midges. When a light source with a power density of about 1.25 W/cm2 is illuminated on the upper surface of the auxiliary pneumatic chamber, the previously non-existent main pneumatic chamber can be expanded quickly within less than 3 s, and generate enormous thrust. This allows the soft robot (length: 3 cm; width: 0.7 cm; weight: 0.36 g) to quickly release from the magnet attractive field and perform a jump with a height of 50.8 cm in less than 1 s, approximately 16 times the body length of the entire soft robot. The proposed soft robot can also be combined with a photothermal bending film to achieve directional crawling. At the same time, by fixing the foot of the soft robot on the base and using light irradiate it, an object weighing about 5 times the overall weight can be ejected to a horizontal distance of 16.9 cm. This untethered pneumatic soft robot has broad prospects in soft jumping robots and wireless actuators, and the proposed pneumatic triggered chamber can also be further applied to other application fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nowadays, the ability of light to remotely and accurately transfer thermal energy has aroused increasing interest among researchers in light-driven soft robots. By combining a variety of soft film materials with different thermal expansion coefficients, soft robots can perform different types of motion behaviors, such as grasping1, crawling2, rolling3, jumping4,5,6, swimming7 and so on. Moreover, mechanical instability can be incorporated to enhance movement speed8. Researches on the combination of photothermal responsive film, humidity responsive film, and electroactive film, with detailed structural design, for the production of soft robots, which can achieve diverse motion behaviors and get excellent motion performance9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. However, due to their light weight and small size, these soft robots can only perform certain common movements, and it is challenging to move objects with masses many times larger than themselves. Some soft robots achieve jumping movements through the combination of soft film materials and magnets, but it is difficult for them to drive other objects to move together17,18. Large soft robots are usually manufactured by combining soft and rigid materials through mechanical design, which can effectively carry large objects, but their mobility is very poor. In order to enable pneumatic soft robots to jump, the size of them will be very large and they always require many pneumatic connection tubes and air pumps to assist in their movement19,20. This enables pneumatic robots to perform the task of grabbing and transporting objects to designated positions by precisely controlling the inflation and inhalation frequency of the air pump21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. Despite the fact that pneumatic soft robots can be manipulated in real-time through the trachea to display specific motion behaviors in various environments and have high sensitivity31,32,33, the overall size of such soft robots is large, and the trachea is bulky and complex. Consequently, pneumatic soft robots are developing towards connectionless wires direction. Researchers are exploring some convenient methods for removing the trachea and preparing soft robots. Recently, the combination of photothermal drive and gas-liquid drive is increasingly applied to the researches of soft robots and actuators34. For example, Wu et al.35 have made a light-driven soft robot that can complete some climbing motions by heating and cooling the internal liquid inside the pneumatic chamber. However, due to the large overall size and slow gas-liquid conversion, it is difficult to make these types of pneumatic soft robots driven by light carry out more kinds of movements.

In this paper, a light-driven untethered pneumatic soft robot with compound motion patterns is prepared, which can be used in the fields of bionic jumping soft robots, directional crawling soft robots, and long-distance throwing actuators. The soft robot is composed of a polyimide (PI) film, a silicone rubber chamber and two small magnets. The thickness of the PI film is 0.25 mm, which possesses high tensile strength, excellent thermal stability, chemical corrosion resistance and mechanical properties. It is the best flexible film for making the body of pneumatic soft robot. Furthermore, the laser engraving technology can be utilized on the 1 mm-thick silicone rubber film to minimize the thickness of the pneumatic chamber, with a magnet encapsulated within the chamber to reduce the overall weight and volume. This structural design method has been demonstrated to enhance the driving performance of pneumatic soft robots. The light-driven untethered pneumatic soft robot achieves a maximum jump height of 53.9 cm and a landing distance of approximately 30 cm following \(1.25\text { W/cm}^2\) of irradiation for a duration of less than 3 s. When a small magnet is employed to fix a thin photothermal film on the bottom of the main body, the soft robot achieves a crawling speed of 0.11 mm/s. When the main body of the soft robot is fixed on the substrate and an object of 2 times its own weight is placed on it, the object can be thrown directionally up to a distance of 49.6 cm, then an object of 5 times its own weight is placed, it can be thrown up to a distance of 16.9 cm. The light-driven pneumatic soft robot is distinguished by its simple processing, low cost and broad application prospects, which greatly promotes the development of the unbound pneumatic soft robot in the direction of high speed and miniaturization.

Experimental section

Materials

In this paper, we utilized 0.25 mm-thick and 0.05 mm-thick polyimide films purchased from Zhongshan Dawn Technology Co., Ltd. (China) for use in our experiments. 1 mm-thick and 0.1 mm-thick silicone rubber films were purchased from Xinghua Zhongjiu Rubber and Plastic Products Factory (China). Furthermore, organosilicon adhesive was purchased from Dongguan Taowei Construction Engineering Co., Ltd. (China). The 7100 e-fluoride liquid was purchased from Shanghai Tengyan Chemicals Trading Co., Ltd. (China) and nano carbon powder was purchased from Hebei Yuanying New Materials Co., Ltd. (China).

Preparation of the pneumatic soft robot

Firstly, a 0.25 mm-thick rectangular PI film is engraved by a 1064 nm laser to make soft robot body with specific structure. Secondly, a carbon dioxide (\(CO_2\)) laser is employed to incise a size of 80 mm*40 mm silicone rubber film to manufacture pneumatic chambers, they can be formed by engraving five times in succession. Then, a silicone adhesive is used to bond the chamber to the circular side of the PI film body, a small magnet is placed in the chamber and a 0.1 mm-thick silicone rubber film of the same size as the upper surface of the chamber is glued on top of it. The assembly of the pneumatic soft robot is completed by attaching a magnet of the same size to the other end of the PI film with a silicone adhesive. Finally, a 0.05 mm-thick polyimide tape is pasted above the side cavity. Use a syringe to plunge from the cavity wall to the inside of the side cavity, vacuum the inside, and then inject the mixed solution, a pneumatic soft robot was obtained.

Characterizations

The motion image and video of the soft robot are captured by the iPhone 13 pro in normal shooting mode and slow-motion mode respectively. The upward thrust of the main pneumatic chamber is measured with a digital push-pull gauge, which was purchased from Wenzhou Weidu Electronics Co., Ltd. (China). The temperature change of the upper surface during laser irradiation is measured by a thermal imager (RX-300, A-BF, China).

Results and discussion

Preparation and structure of a pneumatic soft robot

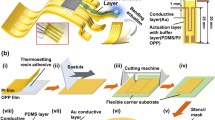

In this article, inspired by the jumping motion of frog and the larvae of gall midges (Asphondylia) (Fig. 1a), a light-driven pneumatic soft jumping robot is composed of a piece of PI film, two magnets, and a specially designed silicone rubber chamber. Figure 1b shows the preparing method of pneumatic soft robot. Firstly, a 0.1 mm-thick aluminum foil layer is positioned on the platform, with a 0.25 mm-thick rectangular PI film on it and then the PI film is engraved by a 1064 nm laser. The aluminum foil can conduct heat with greater efficiency during engraving and make the edges smooth. The 1064 nm laser has an output power of 1 W, an engraving depth of 60%, and an engraving accuracy of 4k. By importing a specific designed structure, the body of the soft robot can be produced. The 0.25 mm-thick PI film was selected to ensure optimal stiffness and excellent fatigue resistance. Moreover, PI film also has good high temperature resistance and insulation properties. Secondly, a carbon dioxide (\(CO_2\)) laser is employed to incise a silicone rubber pneumatic chamber. Here, we put a size of 80 mm*40 mm silicone rubber film on an aluminum metal plate. The power of the \(CO_2\) laser is set to 5.6 W, the engraving speed is 180 mm/s, the step size is 1 mm/s, and silicone rubber pneumatic chambers can be formed by engraving five times in succession. Then, the carved chamber is cleaned by immersing it in an anhydrous ethanol solution for five minutes. Finally, a silicone adhesive is used to bond the chamber to the circular side of the PI film body, a magnet is placed in the chamber and a 0.1 mm-thick silicone rubber film of the same size as the upper surface of the chamber is glued on top of it. After curing, an air chamber with a naturally flat upper surface is obtained. The assembly of the pneumatic soft robot is completed by attaching a magnet of the same size to the other end of the PI film with a silicone adhesive.

Compared with the method of passively exhausting the internal air with the help of atmospheric pressure in previous studies, the designed device can actively expel internal air by directly inserting a syringe. 3M \(Novec^{TM}\)7100 acts as a phase-changing liquid with non-flammability and a suitable boiling point (61 \(^\circ\)C). The rate of vaporization of the fluid can be increased by mixing 7100 e-fluoride and nano carbon powder in a 100:1 ratio. In addition, silicone rubber offers superior elasticity compared to soft materials such as silicone and PDMS. As a result, when the syringe is removed, the needle hole naturally compresses and occludes due to the inherent stress of the material, which greatly reduces the difficulty of manufacturing a photothermal pneumatic chamber. Considering that the silicone rubber retains some degree of permeability, if the internal solution gradually evaporates over an extended period of time during storage, the syringe can be re inserted into the chamber from the cavity wall, and the solution can be injected into the interior again, which makes the soft robot continuously respond to light and heat, greatly increasing the lifespan of the soft pneumatic robot. As shown in Fig. 1c, the overall length of the soft robot is 30 mm, the width is 7 mm, and the total thickness is 1.4 mm. A 0.05 mm-thick polyimide tape with a length and width of 7 mm*5 mm is pasted to the side cavity of the chamber to allow the gas converted from the liquid after illumination to expand above the magnet first. The remaining geometric parameters of the structure are as follows: \(L_{PI} = 30\, \text {mm}, H_{PI1} = 0.25\text { mm}, H_C = H_{Mag} = 1\text { mm}, H_E = 0.1\text { mm}\), \(H_{PI2} = 0.05\text { mm}, L_{IC} = 3\text { mm}, R_{IC} = 5\text { mm}, R_{OC} = 9.5\text { mm}, T_C = 1\text { mm}, L_C = 6\text { mm}, R_{Mag} = 4\text { mm}\).

Bioinspired design of the light-driven pneumatic soft robot based on gas-liquid phase transition chamber. (a) Schematic illustration of bioinspired jumping actuation combining frog-inspired and gall midge larva-like mechanisms. (b) Schematic of the fabrication process for the unconstrained pneumatic soft robot via laser engraving. (c) Structural parameters of the light-driven pneumatic soft robot.

Morphing mechanism and actuation performances of the pneumatic soft jumping robot

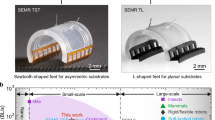

The preparation method of this soft robot is relatively easy. The soft robot needs to be manually bended in advance, the magnets on both sides attracted each other to keep body bent and store elastic potential energy inside. When the auxiliary chamber is irradiated by 808 nm laser, the phase-changing liquid rapidly vaporizes, causing the main chamber to rapidly expand. Concurrently, the distance between the initially attached magnets gradually increases, then the two magnets will detach abruptly. The elastic potential energy accumulated internally will be converted into the kinetic energy of the soft robot to execute the jumping motion (Fig. 2a). To demonstrate the gas movement between the main pneumatic chamber and the auxiliary pneumatic chamber, Fig. 2b shows the chamber variation of the auxiliary chamber under 808 nm laser irradiation with a power density of 1.25 W/cm2. As shown in Fig. 2c, the jumping image is taken with a relatively stable height. After 2.16 s of laser irradiation on the chamber of soft robot, the magnets on both sides detached, the soft robot started jumping at 2.17 s and performed multiple \(360^\circ\) rotations in the air and successfully landed at 3.89 s. In comparison to conventional pneumatic soft jumping robots, this soft robot possesses enhanced degrees of freedom and a faster response time.

As depicted in Fig. 2d, the stable take-off velocity, stable jumping height and stable jumping distance of the soft robot reached 1.68 m/s, 50.8 cm, and 30 cm, respectively. To ensure data accuracy, the jumping height of the soft robot was measured at the lowest point during the jumping process. The velocity of the soft robot was calculated by the vertical displacement (\(\Delta h = h_{2} - h_{1}\)) and corresponding time intervals (\(\Delta t = t_{2} - t_{1}\)) during jumping. The formula used is \(v = (h_{2} - h_{1}) / (t_{2} - t_{1})\), where \(h_{1}\) represents the height at the previous position, \(h_{2}\) represents the height at the current position, \(t_{1}\) represents the time taken to reach the previous position, and \(t_{2}\) represents the time taken to reach the current position. Based on its mass (m = 0.36 g) and stable jumping height, the work done to overcome gravity (\(W_G\) = mgh) of the pneumatic soft robot was calculated to be about 0.00179 J. So that the work efficiency of this soft robot is extremely high. The weight of the different magnet combinations has a significant impact on the jumping height of the soft robot. Consequently, when all other parameters remain constant, Fig. 2e illustrates the correlation between the magnet dimensions on both sides and the resultant jump height of the soft robot. The magnetic force exerted by a combination of a 3 mm*1 mm magnet and a 4 mm*1 mm magnet was insufficient to maintain the PI film in a bent state. Consequently, the experiment is conducted exclusively with 4 mm*1 mm magnets. The jumping heights of the soft robots made of different matching small magnets are different, and the jumping height changes during 20 times of heating and cooling are recorded. As shown in Table 1, we measured the weights of magnets with different sizes. Besides, a more detailed study was conducted on on magnets with diameters of 3 mm, 4 mm, and 5 mm, and thicknesses of 0.5 mm and 1 mm. Different combinations of magnets were attached to a 0.25 mm-thick, 30 mm-long, 7 mm-wide polyimide film, respectively. The activation time and jumping height of soft robots were recorded in Table 2. The findings indicate that the deployment of two 4 mm*1 mm magnets leads to a substantial augmentation in jumping height, exhibiting optimal efficiency. The 4 mm and 5 mm refer to the magnets’ diameter size, and the 1 mm refer to the magnets’ thickness.

Jump performance of the light-driven pneumatic soft robot based on gas-liquid phase transition chamber. (a) Schematic diagram used to analyze jumping mechanism of each step. (b) Schematic diagram of chamber expansion process after illumination. (c) Photographs showing the time-dependent jump behavior of the soft robot, recorded at 240 frames per second (scale bar = 10 cm). (d) Jumping height and velocity of the robot. (e) Jumping heights of the soft robot made with different magnets combinations. (f) Jumping heights of 30 mm-long and 7 mm-wide soft robot triggered by NIR laser with varied power densities (1.25, 2.50, and 3.75 W/cm2). (g) Jumping processes of 7 mm-wide soft robots with different lengths (L = 28, 30, 32, 34 mm) under 1.25 W/cm2 laser irradiation. (h) Jumping processes of 30 mm-long soft robots with different widths (W = 6, 7, 8 mm) under 1.25 W/cm2 laser irradiation. Both (f), (g) and (h) initiate laser irradiation at t = 0 s.

Figure 2f shows the effect of the power of the irradiating laser on the response time. A NIR laser with a power of 3.75 W/cm2 irradiates the auxiliary chamber for 0.6 s, which can propel the soft robot to jump. However, high power density lasers are likely to damage the pneumatic chamber and destroy the reusability of the soft robot. Therefore, a near-infrared laser with a power of 1.25 W/cm2 is used in this experiment. It is also noteworthy that a correlation exists between the overall length, width and thickness of the soft robot and its capacity for jumping height. As shown in Fig. 2g, soft robot made of 28 mm-long PI film can can be activated more quickly, but it exhibits limited long-term durability, its recovery time from excessive bending becomes longer due to flexural fatigue in the 0.25 mm-thick PI film. As shown in Fig. 2h, soft robots with larger widths exhibit significant challenges in achieving bilateral adhesion when using 4*1 mm magnets. Although the 8 mm-wide soft robot demonstrates superior jumping performance, it operates near the critical magnetic adhesion threshold on both sides, the two sides of the soft robot occasionally fail to maintain stable adhesion, resulting in inability to jump. Therefore, we conclude that the 7 mm-wide configuration represents the optimal design when considering jumping height stability. As shown in Table 3, we measured the upward force generated by polyimide films of different thicknesses bent to the same angle. The 0.1 mm-thick polyimide film exhibited minimal upward force, low rigidity, and excessive softness, making it unsuitable for jump-capable soft robots. In contrast, the 0.5 mm-thick film produced a significantly higher upward force but was overly rigid. If used in jumping soft robots, it would require larger magnets for adhesion, substantially increasing the robot’s weight and drastically degrading jumping performance. Therefore, 30 mm-long, 7 mm-wide and 0.25 mm-thick PI film and two 4*1 mm magnets are the best for making pneumatic soft jumping robot.

We conducted a more in-depth study on the forces acting on the soft robot, defining \(F = F_{\text {stress}} + F_{\text {upward expansion force of the chamber}}\). When \(F \le F_{\text {attraction}}\) (the attractive force between magnets), the soft robot remains stable and does not open automatically to jump. When \(F > F_{\text {attraction}}\), the magnets on both sides of the soft robot fail to attract together, causing the two sides of the soft robot to open and initiate a jump. As the length of the soft robot increases, the stress force decreases, requiring a greater upward expansion force of the chamber to make F exceed \(F_{\text {attraction}}\). Consequently, a longer heat accumulation time is needed. During jump initiation, the attractive force between magnets (\(F_{\text {attraction}}\)) decays rapidly to zero, enabling the foot segment to strike the substrate. The resultant ground reaction force \(F_{\text {sub}} = F_{\text {stress}} - G = ma\) (where \(F_{\text {stress}}\) denotes the prestress accumulated during magnetic coupling, \(G = mg\) is the gravitational force, and m is the mass of the soft robot) governs the acceleration and jumping height.

Expansion/recovery characteristics of the soft silicone rubber chamber

To minimize the size of the pneumatic chamber, a new design approach of the chamber has been proposed. The design of the chamber for storing liquid and the chamber for expansion should be undertaken in different positions, as shown in Fig. 3a. When the chamber is irradiated by the laser, the liquid inside vaporizes due to heating, causing the chamber to expand and transition from the state shown in the left image to the state shown in the right image. Similarly, when the laser is removed, the gas inside cools and liquefies, allowing the chamber to return to its initial flat state (Left). Due to a layer of 0.05 mm-thick PI tape attached to the upper side of the chamber for storing liquid, when the laser irradiates the liquid cavity, although the liquid will vaporize into gas, the gas will move towards the chamber for expansion. When the laser is removed, the gas will cool down again into liquid and flow back into the liquid cavity. As shown in the Fig. 3b, the pressure gauge is used to measure the upward thrust of the main chamber when the liquid chamber is illuminated. When the laser is turned on, the reading of the pressure gauge shows a significant upward trend. After the laser is removed, the reading of the pressure slowly returns to its initial reading. Before the measurement, the digital push-pull gauge is placed in parallel alignment with the upper surface of the chamber. Figure 3c shows changes of the surface temperature of the soft silicone rubber chamber. It has been demonstrated that, within 3 s of undergoing irradiation, the surface temperature of the chamber can reach \(108.5\) °C. Following a cooling period of 2 s, the surface temperature of the chamber can be restored to near its initial temperature.

Mechanisms of expansion and recovery of pneumatic chamber. (a) Silicone rubber chamber expansion/recovery state under irradiation and after irradiation cessation. (b) Relationship between the chamber thrust and the irradiation time during expansion/recovery. (c) Photo-thermal performance of the silicone rubber chamber under 1.25 W/cm2 laser irradiation.

Crawling motion of the pneumatic soft robot

Considering application scenarios that require jumping in different positions, a crawling soft robot used as the feet of the jumping soft robot can be added to the soft robot by using a tiny magnet to attach the feet to the tail of the curved soft robot. feet can be added to the soft robot and a tiny magnet is used to attach the feet to the bottom of the curved soft robot. The tiny magnet is in a cylindrical shape with a radius of 1.25 mm and a height of 0.5 mm. The feet of the soft robot are made of a layer of 50 micrometers-thick PI single-layer tape adhered to a 100 micrometers-thick black plastic film, then cut it into a specific shape, as shown in Fig. 4a. By illuminating the individual crawling feet and the soft robot combined with crawling feet with infrared light several times, the designed soft robot can move to a specific position (Fig. 4b,c). The soft robot combined with crawling feet crawls faster than the individual crawling feet. The soft robotic feet primarily leverage the friction between the soft robot and the contact surface. A heavier body increases the foot’s contact pressure with the ground, reducing slippage and improving crawling efficiency. The soft robot with feet is capable of directional crawling at a speed of 0.11 mm/s. It is continuously irradiated by an infrared lamp with a power density of 1.41 W/cm2 for 7 times. After 290 s, the soft robot can complete a significant crawling motion to the left. The surface shown in Fig. 4 is composed of A4 2-side multi-purpose paper, which was purchased from Hefei Yizheng Cultural Products Co., Ltd. (China). Compared with other soft robots used for crawling, the overall combination of soft foot and soft robot also provides ideas for future multifunctional soft pneumatic robots.

Projectile motion of the pneumatic soft robot

Remove the soft feet of the wireless pneumatic soft robot and secure the soft robot to the base using a magnet (4 mm*1 mm) glued to the substrate (Fig. 5a). To enable the soft robot to launch objects, one end (Tail) needs to be fixed to the substrate by the magnet. When an 808 nm laser is directed towards a pneumatic cavity, objects positioned diagonally above the soft robot are projected into the distance. By this method, a novel remote-controlled ejection device was fabricated. As shown in Fig. 5b, an object with a weight of 0.72 g is projected, which has two times the overall weight of the soft robot. Also, the weight of the object is an important factor to consider. Then a 1.8 g object five times the overall weight of the soft robot is projected. Figure 5c shows objects of different weights that can be thrown to different heights and horizontal positions by the soft robot. This also greatly improves the efficiency of soft robots for moving objects.

Discussion of light-driven projectile motion of the pneumatic soft robot. (a) Schematic of the specific setup of throwing object experiments. The basal magnet serves to anchor one side of the soft robot to the substrate. (b) Photographs showing the time-dependent throwing object behavior of the soft robot, recorded at 240 frames per second. (c) The projectile heights and distances achieved when throwing objects of varying weights.

Conclusions

The proposed light-driven untethered pneumatic soft robot does not need to be fabricated through complex processes such as solution preparation. Through fine structural design, the silicone rubber chamber, PI film and small magnets are combined together, which can be easily made in a short time. After adding the pneumatic mixed solution into the chamber, it can be controlled remotely through light, and the reaction speed is very fast, the pneumatic soft robot can jump to a height of 50.8 cm within 3 s. With the removal of the pneumatic tubes, a smaller pneumatic soft robot whose thickness is less than 1.5 mm can be designed through the reasonable internal structure design of the chamber, which can be used more conveniently in a narrow environment. At the same time, the robot can crawl by sticking the simple feet at the bottom of the pneumatic robot. By attaching one side of the pneumatic soft robot to the substrate, a simple ejector can be built, an object weighing five times its own weight can be quickly thrown to a distance of 16.9 cm. Therefore, the proposed pneumatic soft robots have broad prospects in miniaturization and multi motion modes.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Li, Q. & Jiao, Y. Ultrafast photothermal actuators with a large helical curvature based on ultrathin go and biaxially oriented pe films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 55828–55838. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.2c18478 (2022).

Wang, R., Han, L., Wu, C., Dong, Y. & Zhao, X. Localizable, identifiable, and perceptive untethered light-driven soft crawling robot. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 6138–6147. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c20539 (2022).

Luo, X.-J. et al. Multifunctional ti3c2t x mxene/low-density polyethylene soft robots with programmable configuration for amphibious motions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 45833–45842. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c11056 (2021).

Hu, J. et al. Springtail-inspired light-driven soft jumping robots based on liquid crystal elastomers with monolithic three-leaf panel fold structure. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218227. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202218227 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Dual-responsive jumping actuators by light and humidity. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 25337–25346 (2022).

Guo, H., Priimagi, A. & Zeng, H. Optically controlled latching and launching in soft actuators. Adv. Func. Mater. 32, 2108919 (2022).

Yin, C. et al. Visible light-driven jellyfish-like miniature swimming soft robot. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 47147–47154. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c13975 (2021).

Qing, H. et al. Spontaneous snapping-induced jet flows for fast, maneuverable surface and underwater soft flapping swimmer. Sci. Adv. 10, eadq4222. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adq4222 (2024).

Song, X., Qiu, X., Huang, X., Xu, M. & Zhang, L. Light-driven awn-footed soft robots. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 307, 2101003. https://doi.org/10.1002/mame.202101003 (2022).

Han, L. et al. A multidirectional locomotion light-driven soft crawling robot. Adv. Func. Mater. 33, 2305046. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202305046 (2023).

Da Cunha, M. P., Debije, M. G. & Schenning, A. P. Bioinspired light-driven soft robots based on liquid crystal polymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 6568–6578. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0CS00363H (2020).

Guo, Q. et al. An aquatic biomimetic butterfly soft robot driven by deformable photo-responsive hydrogel. Soft Matter 19, 7370–7378. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3SM01027A (2023).

Yu, Z. et al. Fast-response bioinspired near-infrared light-driven soft robot based on two-stage deformation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 16649–16657. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.2c01109 (2022).

Zhao, T. et al. Phototactic miniature soft robots with terrain adaptability. Adv. Mater. Technol. 7, 2101660. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.202101660 (2022).

Yang, Y., Li, D. & Shen, Y. Inchworm-inspired soft robot with light-actuated locomotion. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 4, 1647–1652. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2019.2896917 (2019).

Pan, X. et al. Self-perceptional soft robotics by a dielectric elastomer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 26797–26807. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.4c04700 (2024).

Ahn, C., Liang, X. & Cai, S. Bioinspired design of light-powered crawling, squeezing, and jumping untethered soft robot. Adv. Mater. Technol. 4, 1900185. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.201900185 (2019).

Jeon, G.-H. & Park, Y.-J. Soft jumping robot using soft morphing and the yield point of magnetic force. Appl. Sci. 11, 5891. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11135891 (2021).

He, W., Li, J., Yan, Z. & Chen, F. Bidirectional human-robot bimanual handover of big planar object with vertical posture. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 19, 1180–1191. https://doi.org/10.1109/TASE.2020.3043480 (2021).

Gorissen, B., Melancon, D., Vasios, N., Torbati, M. & Bertoldi, K. Inflatable soft jumper inspired by shell snapping. Sci. Robot. 5, eabb1967. https://doi.org/10.1126/scirobotics.abb1967 (2020).

Terryn, S., Brancart, J., Lefeber, D., Van Assche, G. & Vanderborght, B. Self-healing soft pneumatic robots. Sci. Robot. 2, eaan4268. https://doi.org/10.1126/scirobotics.aan4268 (2017).

He, Q. & Cai, S. Soft pumps for soft robots. Sci. Robot. 6, eabg6640. https://doi.org/10.1126/scirobotics.abg6640 (2021).

Huang, W., Xiao, J. & Xu, Z. A variable structure pneumatic soft robot. Sci. Rep. 10, 18778. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75346-5 (2020).

Diteesawat, R. S., Helps, T., Taghavi, M. & Rossiter, J. Electro-pneumatic pumps for soft robotics. Sci. Robot. 6, eabc3721. https://doi.org/10.1126/scirobotics.abc3721 (2021).

Rajappan, A., Jumet, B. & Preston, D. J. Pneumatic soft robots take a step toward autonomy. Sci. Robot. 6, eabg6994. https://doi.org/10.1126/scirobotics.abg6994 (2021).

Breitman, P., Matia, Y. & Gat, A. D. Fluid mechanics of pneumatic soft robots. Soft Rob. 8, 519–530. https://doi.org/10.1089/soro.2020.0037 (2021).

Sparrman, B. et al. Printed silicone pneumatic actuators for soft robotics. Addit. Manuf. 40, 101860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2021.101860 (2021).

Zhang, B. et al. Spring-reinforced pneumatic actuator and soft robotic applications. Smart Mater. Struct. 33, 105017. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-665X/ad74bf (2024).

Jiao, Z., Ji, C., Zou, J., Yang, H. & Pan, M. Vacuum-powered soft pneumatic twisting actuators to empower new capabilities for soft robots. Adv. Mater. Technol. 4, 1800429. https://doi.org/10.1002/admt.201800429 (2019).

Feng, M., Yang, D., Majidi, C. & Gu, G. High-speed and low-energy actuation for pneumatic soft robots with internal exhaust air recirculation. Adv. Intell. Syst. 5, 2200257. https://doi.org/10.1002/aisy.202200257 (2023).

Wharton, P. et al. Tetraflex: A multigait soft robot for object transportation in confined environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2023.3290409 (2023).

Fan, J. et al. Biologically inspired swimming robotic frog based on pneumatic soft actuators (vol 15, 046006, 2020). Bioinspiration Biomimetics https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-3190/ab835a (2022).

Qi, X., Shi, H., Pinto, T. & Tan, X. A novel pneumatic soft snake robot using traveling-wave locomotion in constrained environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 5, 1610–1617. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2020.2969923 (2020).

Fang, X., Wei, K. & Yang, R. Untethered soft pneumatic actuators with embedded multiple sensing capabilities. Soft Rob. 11, 382–391. https://doi.org/10.1089/soro.2023.0048 (2024).

Wu, J. et al. Light-driven soft climbing robot based on negative pressure adsorption. Chem. Eng. J. 466, 143131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.143131 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61205095). We also gratefully acknowledge Prof. B. Cai, G. J. Xu from USST for their help.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zheqi Zhou: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Visualization. Kejian Chen: Supervision, Methodology, Resources, Writing - review and editing. Yang Shen, Yifan Zhu, Qian Wang, Xiaofen Zeng, Yuke Qin: Methodology, Validation, Writing - review and editing, Visualization. Songlin Zhuang: Methodology, Resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Z., Chen, K., Shen, Y. et al. Light-driven soft robot with compound motion patterns based on gas–liquid phase transition chamber. Sci Rep 15, 18098 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03247-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03247-6