Abstract

A crucial step in the engineering of bioactive materials from sugarcane by-products is understanding their physical, chemical, and biological characteristics, particularly their molecular composition and biological activities. This study aimed to characterize the physicochemical properties of methanolic and aqueous extracts from sugarcane molasses and vinasses, determine their antioxidant capacity, and identify key compounds of biological interest; specifically phenolic compounds (PCs) and heat-induced compounds (HICs). Through non-targeted analytical approaches, we identified a diverse range of PCs and HICs in the extracts. In vitro tests revealed significant antioxidant effects in both aqueous and methanolic fractions, with the methanolic extracts showing superior free radical scavenging capacity. This bioactivity was linked to PCs such as p-coumaric acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde, chlorogenic acid, and schaftoside, as well as HICs like 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one (DDMP); 4-hydroxy-2,5-dimethyl-3(2H)-furanone (HDMF); 2,6-dimethoxyphenol; and 1,6-anhydro-β-D-glucopyranose. These findings underscore the potential of sugarcane molasses and vinasses as sources of bioactive compounds, which can be engineered into new materials with promising biological properties for health, pharmacological, and food industry applications. Furthermore, our research highlights the integration of bioengineering, material science, and sustainable practices within the sugarcane industry by promoting the valorization of by-products, contributing to resource efficiency and industrial innovation under circular economy principles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In an era increasingly focused on sustainable development, resource optimization, and minimizing environmental impacts, applied research has made substantial strides in addressing challenges related to the industrial transformation of raw materials and the inevitable generation of waste1,2. The agro-industrial sector, particularly the sugarcane industry, generates significant amounts of by-products, including molasses and vinasses, which, if not properly managed, can pose considerable economic and environmental concerns3,4,5. Molasses, a viscous by-product produced during the crystallization of sugarcane juice, and vinasses, a liquid residue from ethanol production, have been traditionally used in animal feed and soil fertilization6,7. However, these uses do not fully exploit their real value, especially considering that these by-products contain a wide variety of compounds that could be repurposed as bioactive materials for health, pharmacology, and food industry applications8,9,10.

One of the most extensively studied groups of compounds in this context is phenolic compounds (PCs), a class of secondary metabolites naturally synthesized by plants during growth. PCs play crucial physiological roles in the adaptive response to various stress factors11. Many of these phytochemicals have been found in sugarcane extracts and are associated with medicinal properties, demonstrating positive relationships with several cellular effects, including anti-inflammatory, cytoprotective, immunomodulatory, antimicrobial, and antiproliferative activities8,12,13,14. In addition, industrial transformation processes applied to plant-based or agricultural products, such as sugarcane, can lead to the formation of additional compounds, specifically heat-induced compounds (HICs), resulting from interactions among naturally occurring components during thermal treatments. Among the most studied HICs are Maillard reaction products (MRPs), formed through reactions between reducing sugars and free amino groups of peptides and proteins15. Particularly for sugarcane, MRPs can be generated throughout its industrial processing, beginning at harvest, but they are primarily formed during juice clarification and evaporation8. While many of these compounds have been widely described for their contribution to the flavor, color, and aroma of various food products15,16, some studies have also explored the bioactive potential of certain HICs formed during heat treatment, highlighting their antioxidant capacity and other biological activities17,18,19,20, thus making them promising candidates for use in engineering bioactive materials.

In processed materials derived from agricultural products, such as sugarcane, it is essential to consider not only the presence of plant secondary metabolites but also their potential coexistence with processing-induced compounds, as both may influence the capacity of these materials to exert specific biological effects. Although processing can alter the composition and structure of certain PCs, this does not necessarily lead to a reduction in the overall bioactive potential of the materials. On the contrary, thermal treatments may promote the formation of new compounds, such as HICs, that can retain or even enhance biological activity, either through additive, synergistic, or protective interactions21,22,23. Despite the biological relevance of both compound classes, few studies have addressed their independent characterization23,24,25. This study contributes to filling that gap by evaluating PCs and HICs separately, providing insight into their individual presence and bioactive capacity in sugarcane molasses and vinasses.

In the specific context of sugarcane-derived products, the potential of some products, by-products, and waste materials as sources of bioactive compounds has been documented26,27,28. However, this potential has mainly been attributed to secondary metabolites such as terpenes and phenolic compounds, with less attention given to compounds formed during the manufacturing process. By evaluating the physicochemical characteristics, antioxidant properties, and chemical profiles of separately obtained extracts, this study provides insights into the presence, diversity, and potential bioactivity of PCs and HICs in sugarcane molasses and vinasses, thereby contributing to a deeper understanding of these compounds in such by-products. Consequently, the main objective of this research was to independently characterize both PCs and HICs in sugarcane molasses and vinasses using non-targeted analytical approaches. This comprehensive analysis could open new avenues for the valorization of these two by-products and support sustainable innovation in the sugarcane industry. It also aims to identify key molecules that could serve as the basis for developing novel bioactive materials, potentially applicable as functional ingredients or prototypes for nutraceutical and pharmaceutical uses. A simplified visual summary of the study’s experimental strategy and main findings is presented in Fig. 1.

Materials and methods

Materials and reagents

Folin–Ciocalteu reagent; 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical (DPPH); 2,2-azino-bis-[3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid] (ABTS); 2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine (TPTZ); and the standards of gallic acid and Trolox were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich. HPLC-grade solvents like methanol and acetonitrile were purchased from VWR Chemicals. Ultrapure water was obtained from a Millipore system. All other chemicals and reagents utilized were of analytical grade.

Sample preparation

For this study, two by-products of the sugarcane industry were used: molasses and vinasses. The molasses samples were obtained from Ingenio San Carlos, and the vinasses from Ingenio Mayagüez, both located in the Valle del Cauca region in Colombia. These facilities operate under continuous and standardized industrial processes and were selected to ensure consistency across the analyzed samples. Once received, all the samples were refrigerated (approx. 4 °C) until use. Before each test, the samples were diluted in distilled water to appropriate concentrations to facilitate processing and data collection. The respective dilution factor was considered for each analysis, and the results were expressed in dry matter. All diluted samples were homogenized and filtered through a filtering aid (Celite® 545—Merck Millipore) to remove any interfering agents.

General characterization of by-products

The molasses and vinasses were characterized regarding dry matter content (DMC—%), total soluble solids (TSS—°Brix), pH, and density. DMC was determined using a gravimetric method with vacuum drying for 24 h (65 °C ± 2 °C, 13 kPa)29.TSS were quantified by measuring the refractive index at 20 °C using a refractometer with electronic temperature control and converting the values to °Brix. pH readings were taken using a digital pH-meter. The density was calculated based on the ratio of mass to volume of the samples, both measured at the time of performing the dilutions required to facilitate data collection.

Extraction of compounds of biological interest

Two main groups of molecules were considered as compounds of biological interest in this study: PCs, mostly originated during the secondary metabolism of sugarcane; and HICs, formed during the thermal processing applied in the industrial transformation of sugarcane. HICs included MRPs and other volatile and low molecular weight compounds. The extracts were obtained following a solid-phase extraction (SPE) procedure implemented by Caderby et al.24 with some adaptations30,31. The molasses and vinasse samples were diluted in acidified water (pH 2.0 ± 0.2 with 37% HCl) at a 1:10 ratio. These solutions were shaken in an ultrasonic bath for 15 min and then centrifuged at 10,000×g for 10 min. The resulting supernatants were vacuum filtered through a 0.45 µm cellulose nitrate membrane to remove solid particles. The recovered filtrates were injected into cartridges packed with reverse-phase polymeric sorbent (Oasis® HLB, 3 mL, 60 mg—Waters) previously conditioned by sequentially passing 3 mL each of methanol and acidified water (pH 2.0). In this step, the PCs were retained on the sorbent while the HICs passed through and remained in the filtrate. To maximize the extraction of the HICs, the cartridges were washed with 3 mL of acidified water at a drop-wise flow rate (approx. 0.1 mL min−1), obtaining an aqueous filtrate presumably rich in HICs (extracts A). Subsequently, the PCs retained on the cartridges were eluted with methanol in two applications of 3 mL each at slow flow rate, generating a methanolic fraction potentially rich in PCs (extracts B). Once extracts A and B were obtained for both the molasses samples (EMA and EMB) and the vinasse samples (EVA and EVB), they were neutralized to pH 7.0 ± 0.2 and subjected to ultrafiltration using regenerated cellulose centrifuge filters with a nominal molecular size cutoff of 3 kDa (Amicon® Ultra 2 mL, 3 K—Merck Millipore). The manufacturer’s recommendations regarding time and relative centrifugation force were followed for this process. The filtered fractions were recovered for each type of sample and stored under refrigeration (approx. 4 °C) in dark conditions until further analysis.

Quantification of total antioxidant compounds (TAC)

The TAC content of both the molasses and vinasse samples, as well as their respective extracts, was quantified spectrophotometrically using the Folin-Ciocalteu test, following the protocol of Singleton et al.32 with some modifications33. Gallic acid (GA) was used as the standard, and distilled water as the blank sample. In a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube, 600 µL of distilled water were mixed with 10 µL of the standard solution, the blank sample, or the sample to be analyzed. Immediately, 50 µL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was added, the solution was shaken and allowed to react for 1 min. After this time, 150 µL of a 20% (w/v) Na2CO3 solution was added, the mixture was stirred, and 190 µL of distilled water were added to complete a volume of 1 mL. After 120 min of incubation in the dark and at room temperature (approx. 23 °C), 300 μL of the mixture were transferred into a 96-well microplate spectrophotometer reader, and the absorbance at 760 nm was measured. Based on the absorbance values of the standard solution at five different concentrations, a calibration curve was constructed, allowing the calculation of the total concentration of antioxidant compounds in the analyzed samples. The TAC content was expressed as mg equivalents of GA per g of dry matter (mg GAE g−1).

Determination of antioxidant capacity

The antioxidant capacity of the extracts was evaluated based on their potential for free radical scavenging. Three in vitro assays were applied: DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP (Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power).

DPPH assay

The procedure proposed by Brand-Williams et al.34 was applied with some modifications35,36, using Trolox as the standard and methanol as the blank sample. Briefly, 300 μL of a 0.1 mM DPPH radical methanolic solution were transferred to a 96-well plate and mixed with 15 μL of the standard solution, the blank sample, or the extract to be analyzed. The plate was kept in the dark for 30 min at room temperature, after which the solution absorbance was measured at 517 nm. The antioxidant activity was expressed as the inhibition percentage (I) according to Eq. (1):

where A0 and A are the absorbance values of the blank sample and the extracts studied, respectively. Based on the inhibition percentages of the standard solution at five different concentrations, a calibration curve was constructed to calculate the Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC) of the extracts, which was expressed in micromoles of Trolox Equivalents (TE) per gram of dry matter (μmol TE g−1). Additionally, the results were expressed in terms of the IC50 value, which refers to the concentration of the extract required to achieve a 50% inhibition of the radical. This parameter was calculated from the function that relates the percentages of inhibition reached by the extracts at different concentrations35,37.

ABTS assay

The ABTS assay was performed following the method described by Re et al.38 with specific modifications27,39,40. Trolox served as the standard, and ethanol was used as the blank sample. The ABTS radical cation (ABTS·+) was generated by mixing a 2.45 mM solution of K2S2O8 and a 7 mM solution of the ABTS reagent in a 1:1 volumetric ratio. This mixture was allowed to react in the dark at room temperature for 16 h to form the ABTS·+. The resulting radical solution was then diluted with ethanol to achieve an absorbance of 0.7 ± 0.02 at 753 nm. For the assay, 300 μL of the diluted ABTS·+ solution were transferred into a 96-well plate, followed by 4 μL of the standard solution, the blank sample, or the extract to be analyzed. The plate was incubated in the dark at room temperature for 6 min. After incubation, the absorbance was measured at 753 nm. In the same way as in the DPPH assay, the results of this test were expressed as TEAC (µmol TE g−1) and IC50.

FRAP assay

The adaptations of the Benzie & Strain method41,42 suggested by Pulido et al.43 and other authors44,45 were followed. Trolox and FeSO4 were used as standards, and distilled water was used as the blank sample. Prior to each test, the FRAP reagent was prepared and kept in a water bath at 37 °C throughout the process. The FRAP reagent was made by mixing the following solutions in a 10:1:1 volume ratio: 300 mM acetate buffer (pH 3.6), 20 mM FeCl3, and 10 mM 2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine (TPTZ) dissolved in 40 mM HCl. In a 96-well plate, 285 μL of freshly prepared FRAP reagent were mixed with 15 μL of the standard solution, the blank sample, or the extract to be analyzed. This mixture was incubated at room temperature for 30 min in the dark, after which the absorbance was measured at 593 nm. Calibration curves were constructed based on the absorbance values of Trolox and FeSO4 standard solutions at five different concentrations. These curves were used to calculate the FRAP value of the extracts by interpolating from their absorbance values. The antioxidant capacity was expressed as FRAP value in equivalent micromoles of Trolox and ferrous sulfate per gram of dry matter (μmol TE g−1 and μmol FeSO4 g−1, respectively).

Identification of PCs and HICs present in the extracts

The profile of main compounds present in the molasses and vinasse extracts was obtained. PCs contained in the methanolic fractions (extracts B) were analyzed by liquid chromatography (LC), while HICs in aqueous fractions (extracts A) underwent analysis using gas chromatography (GC). In both cases, these separation techniques were coupled to high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS).

Characterization of the phenolic profile of extracts by LC–MS analysis

The methanolic extracts of molasses and vinasses (EMB and EVB) were analyzed using an ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography system (Agilent 1290—Agilent Technologies) coupled to a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Agilent 6540—Agilent Technologies) equipped with an electrospray ionization source (Agilent Jet Stream—Agilent Technologies) (UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS). The protocol suggested by Ballesteros-Vivas et al.46 was followed. For chromatographic separation, a Zorbax® Eclipse Plus C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 µm particle diameter—Agilent Technologies) was used. The separation was performed at 40 °C with a gradient elution program. The mobile phases consisted of 0.01% (v/v) formic acid in water (eluent A) and 0.01% (v/v) formic acid in acetonitrile (eluent B). The injection volume of the samples was fixed at 2 µL with a flow rate of 0.5 mL min−1. The gradient elution was applied as follows: 0–30% B in 0–7 min, 30–80% B in 7–9 min, 80–100% B in 9–11 min, 100% B in 11–13 min, 0% B in 13–14 min, followed by a 3-min conditioning cycle under the same conditions for the next analysis. To obtain the MS and MS/MS spectra, the mass spectrometer was operated in negative ion mode. The parameters for MS analysis were as follows: capillary voltage of 3000 V, nebulizer pressure of 40 psi, drying gas flow rate of 8 L min−1, gas temperature of 300 °C, skimmer voltage of 45 V, and fragmentor voltage of 110 V. The MS and auto MS/MS modes were set to acquire m/z values ranging between 50–1100 and 50–800, respectively; at a scan rate of 5 spectra per second. Agilent MassHunter Workstation Qualitative analysis software (version 10.0) was used for post-acquisition data processing. Accurate mass data, isotopic patterns, MS/MS fragmentation patterns, MS databases search, and bibliographic search were employed for the tentative identification of PCs present in the analyzed extracts.

Characterization of the volatile profile of extracts by GC–MS analysis

The aqueous extracts of molasses and vinasses (EMA and EVA) were analyzed using a gas chromatography system (Agilent 7890B—Agilent Technologies) coupled to a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Agilent 7200—Agilent Technologies) equipped with an electronic ionization interface (GC-EI-QTOF-MS). The protocol suggested by Ballesteros-Vivas et al.46 was followed with some modifications. For chromatographic separation, a DuraGuard capillary column (DB-5 ms, 30 m + 10 m, 250 µm internal diameter, 0.25 µm film thickness—J&W Scientific, Agilent Technologies) was used. Helium served as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 0.8 mL min−1. The splitless mode was used for injecting 1 µL of the extract, with the injection temperature maintained at 250 °C. The GC oven temperature program was initially set at 60 °C for 1 min, then increased gradually at a rate of 10 °C min−1 to 325 °C, and held at this temperature for 10 min. The MS detector was operated in full-scan acquisition mode over a mass range of 50–600 Da, with a scan rate of 5 spectra per second. The MS parameters were as follows: electron impact ionization at 70 eV, transfer line temperature of 290 °C, mass analyzer temperature of 150 °C, and ionization source temperature of 250 °C. Tentative identification of the compounds was performed by systematic deconvolution of the mass spectra from the chromatographic signals using the Agilent MassHunter Unknowns Analysis tool (version 10.2) linked to the NIST MS database (version 20).

Statistical analysis

All measurements were performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as mean values ± standard deviation. Statistical validation was conducted using a completely randomized analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post hoc analysis to identify specific differences among groups. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to examine the relationships between the studied variables. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (PASW Statistics 18, version 18.0.0).

Results and discussion

Physicochemical characterization of sugarcane molasses and vinasses and their extracts

Table 1 presents the physicochemical characterization of the molasses and vinasses samples analyzed in this study. The pH and density values for both materials fall within the typical ranges documented in literature47,48,49. Specifically, the DMC and TSS values found in the molasses comply with the limits defined by the Colombian Technical Standard NTC 587/199450. In contrast, the DMC and TSS values for vinasse were lower than those reported in previous studies49,51,52. This variability is not unusual, as the composition of organic and inorganic matter in vinasse can fluctuate based on variables such as the type of raw material used and the specific processing conditions applied during its generation24,47.

Regarding TAC, these were measured using the Folin-Ciocalteu test. Although this test is typically used to estimate total PCs, it is well known that the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent reacts with any reducing molecule. Therefore, this test quantifies the total antioxidant agents present in a sample26,39,53. Based on this, the analyzed vinasses revealed a significantly higher concentration of TAC compared to molasses (p < 0.05). This result is consistent with previous findings28. However, a discrepancy was observed between the TAC content of the vinasse samples in this study and the values reported in the literature24,28.

Even recognizing these differences, sugarcane molasses and vinasses have been highlighted as by-products of special interest due to their content of molecules with bioactive properties derived from their antioxidant power. Evidence suggests that the concentration of these compounds can increase in some of the products and by-products obtained from sugarcane during the industrial processing26,28,54. Considering that various HICs with antioxidant activity (e.g., MRPs) are synthesized during sugarcane processing, it is likely that their presence adds to that of compounds from the plant’s secondary metabolism (including PCs), potentially contributing to the increase in the overall concentration of TAC in some factory by-products, particularly molasses and vinasses55,56. Additionally, since these types of compounds are not consumed by yeasts during fermentation and are not degraded in the distillation processes involved in ethanol production, their concentration is expected to be higher in vinasses24,28.

From the SPE process applied to the molasses and vinasse samples, two extracts were obtained for each by-product: one aqueous (EMA and EVA) and one methanolic (EMB and EVB). Figure 2 illustrates the TAC concentration of the extracts relative to that of the initial samples. For both by-products, the aqueous fractions exhibited a significantly lower TAC concentration compared to the methanolic fractions (p < 0.05). Specifically, the EMA and EVA extracts contributed 47% and 30%, respectively, of the TAC relative to the initial samples, whereas the EMB and EVB extracts showed higher TAC contributions of 96% and 70%. Additionally, statistical analysis indicated that the type of by-product from which each fraction was derived did not significantly affect the TAC values (p > 0.05), as the TAC levels for each type of fraction remained within relatively similar ranges.

A review of the published literature about TAC in sugarcane molasses and vinasses extracts, revealed some limitations that complicate direct comparisons of results. These limitations include variability in sample origin and differences in extraction and measurement protocols. Despite these challenges, this study highlights the potential of sugarcane by-products as significant sources of antioxidant molecules. The TAC values observed in this study are comparable to those reported for other agro-industrial waste, such as grape pomace (ranging from 21.4 to 11.6 mg GAE g-1)57, litchi seeds (17.9 mg GAE g−1)58, cauliflower waste (9.2 mg GAE g−1)59, and garlic waste (6.91 mg GAE g−1)60. Additionally, sugarcane by-products exhibit higher TAC values than other by-products, such as potato peels (5.40 mg GAE g−1)59, banana peels (3.8 mg GAE g−1)58, and Kinnow seed (3.68 mg GAE g−1)58.

Antioxidant capacity of the extracts

Table 2 presents the results corresponding to the ability of the extracts to scavenge free radicals, assessed by three in vitro tests: DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP. From the results obtained, it was evident that the antioxidant capacity values expressed in TE were generally higher with the ABTS method, while the DPPH method yielded the lowest values. These findings align with expectations, as the DPPH method is more selective in scavenging free radicals via hydrogen atom transfer (HAT mechanism), given that the radical does not react with aromatic acids containing only one hydroxyl group61. In contrast, the ABTS method generates a higher antioxidant response due to a synergistic effect, where molecules with low-volume aromatic ring systems have better access to the radical site, reacting quickly by single-electron transfer (SET mechanism), while antioxidants with more complex structures react more slowly via HAT53,62. The FRAP method, unlike the previous two, exclusively measures active compounds through SET, resulting in similar outcomes to the ABTS method. However, due to the acidic conditions required during the test to protect iron solubility, FRAP values in TE are usually lower than those from the ABTS assay28,53.

As shown in Table 2, regardless of the test applied, the molasses extracts (EMA and EMB) demonstrated higher antioxidant activity compared to the vinasse extracts (EVA and EVB), as indicated by significantly higher TEAC and FRAP values (p < 0.05) and lower IC50 values. Additionally, when comparing the two fractions extracted from each sample, it was found that, for both molasses and vinasse, the methanolic extracts (EMB and EVB) exhibited superior free radical scavenging performance compared to the aqueous extracts (EMA and EVA). These results are consistent with the findings from TAC quantification, indicating a strong correlation between these two variables (0.863 < r < 0.949; p < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

Although the potential of certain products, by-products, and waste from the sugarcane industry as sources of antioxidant compounds has been documented26,27,28,39, the separation of PCs and HICs from these materials as independent fractions has not been widely explored. In fact, only one study has been known in which sugarcane vinasse samples revealed a behavior opposite to that previously described, where sugarcane vinasse samples demonstrated that the contribution to the overall antioxidant activity was more significant in the HIC-rich fractions (specifically MRPs) than in the PC-rich fractions24. Considering that these two types of compounds present in sugarcane by-products have notable antioxidant potential but originate from different processes (PCs from the plant’s secondary metabolism and HICs generated during thermal industrial processes), these differences are interesting, since they provide an opportunity to continue exploring the separation of these fractions and their characteristics.

Characterization of the extracts in terms of their compounds of biological interest

The extracts obtained from molasses and vinasse samples were subjected to chromatographic separation and MS/MS analysis. Tentative identification of the compounds was achieved by comparing MS data (exact mass, isotopic distribution, and fragmentation pattern) with information from the literature and specialized databases (e.g., Metlin, HMDB, and NIST). For LC–MS, acceptance criteria included a maximum difference of 5 ppm between theoretical and experimentally measured molecular ions and an ion abundance threshold of 1000 counts. For GC–MS, compounds were accepted based on a coincidence factor greater than 70%. Profiles of the tentatively identified compounds in each extract are described below.

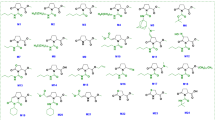

Profile of PCs identified in methanolic extracts of molasses and vinasses (EMB and EVB)

The UHPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS analysis of EMB and EVB extracts identified a total of 18 compounds in the EMB extract and 19 in the EVB, predominantly phenolic acids, and some flavonoids, both in free and conjugated forms. Detailed information about these compounds is provided in Table 3. Some compounds showed multiple correspondences, indicating the presence of different isomers with the same exact mass.

Comparing the PCs profiles, 15 compounds were identified in both extracts, of which 67% exhibited similar relative abundance values with no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05). Among these, compounds such as an isomer of feruloylquinic acid (B10), p-coumaric acid (B17), and schaftoside (B18) were particularly relevant. Specifically, p-coumaric acid was the most abundant PC in the EMB extract and the second most abundant in EVB, accounting for 14.9% and 17.6% in each case. On the other hand, the remaining compounds showed a different pattern, displaying significant differences in relative abundance between the two extracts (p < 0.05). In this category, compounds B01, B04, B05, B07, B13, B14, B16, and B19 were more abundant in the EMB extract. Explicitly, 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde (B13); one isomer of chlorogenic acid (B04); 2,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid (B14); and 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (B05) had relative abundances of 13.9%, 8.5%, 8.0%, and 7.6%, respectively. In contrast, the EVB extract exhibited higher relative abundances of compounds B03, B04, B05, B07, B09, B11, B13, B14, and B22, with 2,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid (B14); 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (B05); 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde (B13); and one isomer of chlorogenic acid (B04) being the most prominent, with respective abundances of 22.4%, 11.9%, 4.6%, and 4.4%. To be precise, B14 was the most predominant compound in the EVB extract.

Multiple studies have cataloged sugarcane and its derivatives as significant sources of various phenolic acids and flavonoids, primarily in glycoside forms26,54,63,64. It is well-established that the phenolic structures in sugarcane stalks are progressively released during industrial processing, leading to higher concentrations of PCs in the by-products28,55,56. This phenomenon is attributed to milling processes that induce enzymatic reactions, promoting the methylation of caffeic acid to ferulic acid and facilitating the hydrolysis of lignin and hemicellulose in the cell wall, thereby releasing PCs such as vanillin and p-coumaric acid26,54,56. According to the above, the obtained results align with previous reports on molasses, which have documented the presence of these and other PCs identified in this study. Specifically, p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde, schaftoside, and several quinic acid derivatives have been identified as significant components26,35,54,63,65. Regarding vinasses, although their phenolic profile has not been extensively studied, several of the compounds identified here align closely with those previously reported for this by-product24.

After examining the PCs profile of the extracts, the similarity in TAC observed between EMB and EVB (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2) can be attributed to the common presence of conjugated double bonds and multiple hydroxyl groups in the identified compounds, which confer optimal chemical properties for free radical scavenging28,66,67. Many of these compounds are well-documented for their antioxidant activity. Nonetheless, the specific characteristics of certain compounds in each extract may account for the observed differences in antioxidant responses (p < 0.05) (Table 2), since as is known, antioxidant activity increases with the degree of hydroxylation66,67. Accordingly, the molecular structures of compounds such as dihydroferulic acid 4-sulfate (B01), chlorogenic acid (B04), and apigenin-6,8-C-diglucoside (B19) may enhance the antioxidant capacity of the EMB extract due to a higher hydroxyl content. In contrast, the simpler structures of the compounds identified in EVB might contribute to the lower antioxidant performance observed in this extract across the in vitro assays conducted in this study (Fig. 4).

Profile of HICs identified in aqueous extracts of molasses and vinasses (EMA and EVA)

GC–MS analysis of the EMA and EVA extracts revealed several volatile compounds, including some phenols, acids, pyranones, furanones, and alcohols. Following the established acceptance criteria, 17 compounds were tentatively identified in the EMA extract and 19 in the EVA extract. Among the identified molecules, only six compounds were common to both extracts, indicating significant differences in the volatile profiles of EMA and EVA. Table 4 summarizes the compounds tentatively identified in sugarcane molasses and vinasses extracts via GC–MS. To provide a more comprehensive evaluation of the results, the relative abundance of each compound was analyzed based on the percentages of their respective chromatographic peak areas.

Six compounds were identified in both extracts (A07, A11, A22, A24, A25, and A30). Among these, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one (DDMP) (A07) was the predominant compound in EMA (22.94%) and the third most abundant in EVA (7.60%). Another notable compound in the EMA extract is 4-methylcatechol (A10), which has been associated with inducing apoptosis in various cancer cells68,69,70. Interestingly, the EVA extract was more outstanding in terms of molecules with relevant biological activities. For instance, 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol (A09) is a recognized aromatic compound with proven anti-inflammatory properties71,72,73,74. Additionally, compounds such as the 2,6-dimethoxyphenol (A13); 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (A17); and 1,6-anhydro-β-D-glucopyranose (A18) have been previously described as molecules with antioxidant functionality75,76,77,78.

Comparing the results of this study with existing literature reveals that several compounds tentatively identified in the EMA and EVA extracts have also been detected in various sugarcane industry derivatives. Notable examples include 4-hydroxy-2,5-dimethyl-3(2H)-furanone (HDMF) (A03); DDMP (A07); 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol (A09); 2,6-dimethoxyphenol (A13); 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (A17); and 3,4-dimethoxyphenol (A29). These compounds have been documented in the volatile profiles of sugarcane derivatives such as clarified juices, brown sugar, and non-centrifugal sugarcane (NCS)39,79,80,81,82, as well as in by-products like molasses and vinasses83,84,85. These findings align with established expectations, as the specialized literature indicates that these types of compounds are commonly produced during the thermal processing of sugarcane juices79. Given that sugarcane is rich in reducing sugars and free amino acids, the temperature and pH conditions prevalent in juice clarification and evaporation processes are conducive to Maillard reactions, which are known to generate a range of volatile compounds, including those identified in this study8. Among the molecules found in the analyzed extracts, HDMF (A03); DDMP (A07); and 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (A17) are recognized MRPs17,18,86,87. These compounds not only contribute to the sensory attributes of thermally processed products (such as aromas, flavors, and colors), but also exhibit significant biological properties, particularly as antioxidants17,18,87,88,89. While the Maillard reaction is complex and generates a diverse range of products, the understanding of factors influencing the biological effects of MRPs remains limited. However, in vitro studies suggest that some MRPs exert their bioactive effects by reducing oxidative damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS), acting as reducing agents and metal chelators15,90.

Other molecules identified that could be considered HICs are 2,6-dimethoxyphenol (A13) and 1,6-anhydro-β-D-glucopyranose (A18). These compounds, found in the EVA extract, have been studied for their antioxidant potential77,78. They are thought to result from the thermal decomposition of polymers like lignin and cellulose and are commonly used as distinctive markers of intensive biomass heating91,92.

Despite the statistically similar TAC contents of the EMA and EVA extracts (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2), the differential composition of HICs may partially account for the observed differences in their antioxidant responses (p < 0.05) (Table 2). However, the superior in vitro free radical scavenging activity of the EMA extract compared to EVA cannot be solely attributed to their number of molecules, as the EMA extract contained fewer compounds than EVA. This suggests that the bioactive potential of the extracts is not exclusively dependent on the quantity or concentration of identified compounds but also on their chemical nature93. Structural factors, such as molecular size and the types of active functional groups in the identified compounds in each extract (Fig. 5), likely play a significant role in the observed differences in antioxidant activities between EMA and EVA90,94.

Given that the characterization of EMA and EVA extracts was conducted tentatively, the precise identification of some compounds detected in the chromatographic analysis remains unresolved. Thus, further studies using different methodological approaches are necessary to accurately identify all compounds present in each extract. Additionally, due to the complexity of the analyzed samples, isolating, purifying, and evaluating each compound individually to identify specific antioxidants presents significant challenges. Therefore, the pragmatic approach adopted in this study confirmed the antioxidant and bioactive potential of the aqueous extracts of molasses and vinasses by associating it with the combined presence of various volatile molecules. Despite these limitations, our results are consistent with existing evidence, as they highlight the presence of HICs also found in other diverse sources such as roasted mustard seed oil76, maple syrup extracts95, dehydrated tamarind pulp77, heated potato fiber96, and dark malt extracts90. These sources, like sugarcane molasses and vinasses, share the common characteristic of undergoing industrial transformation processes involving similar thermal treatments.

Discussion

To explore the potential of sugarcane molasses and vinasses as viable bioactive materials, this research focused on studying the in vitro antioxidant properties of two specific groups of compounds extracted from these sources: PCs, as products of the secondary metabolism of the sugarcane, and the HICs formed during thermal processing. Both groups of compounds were selectively recovered from the sugarcane molasses and vinasses in methanolic and aqueous fractions and were then evaluated comparatively in terms of chemical composition and antioxidant capacity.

The results indicated that both TAC and antioxidant activity were significantly higher in the methanolic extracts (EMB and EVB) compared to the aqueous extracts (EMA and EVA) (p < 0.05), regardless of the by-product analyzed. This disparity can be attributed to the differential composition of each fraction. As expected, the methanolic extracts contained a higher abundance of PCs, including various phenolic acids and flavonoids, while the aqueous fractions comprised a diverse mixture of molecules, including some MRPs. In this sense, these differences in chemical composition are likely responsible for the observed variations in radical scavenging capacities between the extracts.

It is well-established that the antioxidant properties of a substance are influenced by specific structural factors, such as the degree of unsaturation, the presence and positioning of functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, methoxyl, and sulfhydryl), and the substance’s ability to restore itself after neutralizing free radicals66,93,94,97. Although the volatile compounds identified in the aqueous extracts have molecular structures with antioxidant-active groups, the PCs found in the methanolic extracts have more extensive polyunsaturated conjugated systems and high degrees of hydroxylation. These structural features make them more prone to neutralizing free radicals through electron or hydrogen transfer mechanisms98,99.

Although the antioxidant activity of PCs and HICs present in molasses and vinasses was assessed in separate extracts, both compound groups were obtained from the same sugarcane-derived matrices. This coexistence reflects the compositional complexity of these by-products and suggests that the combined presence of PCs and HICs may enhance their bioactive properties through complementary mechanisms. Molecules with diverse functional groups and physicochemical characteristics may act at multiple levels of radical neutralization, potentially broadening the overall bioactive effect99. PCs typically exert their antioxidant effects by donating hydrogen atoms or electrons to neutralize free radicals and by chelating metal ions53,93,94. In turn, HICs, such as MRPs, can also scavenge radicals and chelate metals through distinct functional groups, including heterocyclic nitrogens and reductones15,25,100. This functional complementarity reinforces the value of sugarcane by-products as promising sources for antioxidant recovery.

While bioactive potential is often investigated by evaluating one analyte at a time, the non-targeted approach applied in this study provided a more comprehensive view of the bioactive properties of sugarcane by-products. This approach not only enabled the identification of molecules previously reported for their significant biological activities but also revealed unnoticed compounds that, while requiring further validation, could broaden the spectrum of biologically relevant molecules and help address unresolved phenomena. This perspective enhances our understanding of how sugarcane by-products can be harnessed as sources for engineering of bioactive materials, offering new possibilities for future applications.

Beyond the findings presented in this study, it is important to consider that, as with most agricultural-origin products, the composition and bioactivity of sugarcane molasses and vinasses may be influenced by factors such as variety, cultivation conditions, or industrial processing parameters47,101,102. Although these aspects were not the focus of the present study, they represent relevant directions for future research. Still, the results obtained here under controlled conditions offer a solid basis for understanding the contribution of PCs and HICs to the antioxidant potential of sugarcane by-products.

The antioxidant effects observed between the methanolic and aqueous extracts underscore the value of sugarcane molasses and vinasses as notable sources of bioactive compounds. Given that antioxidant activity is often correlated with other bioactive properties99, these findings provide a solid foundation for further research into broader bioactivities that could be harnessed across multiple application fronts. Future work should include evaluating additional biological properties of these extracts, such as their antiproliferative potential in specific cellular contexts, and assessing their suitability for integration into functional systems. Potential applications could include functional food development, nutraceutical formulation, pharmacological prototypes, and bio-based materials design; particularly in strategies where oxidative stress modulation plays a central role. These perspectives further support the role of sugarcane by-products in the development of sustainable bioactive materials, with relevance across multiple sectors such as healthcare, nutrition, and materials science.

Conclusions and future work

The results of this study confirm the potential of sugarcane molasses and vinasses as sources of bioactive compounds. Both methanolic and aqueous extracts showed similar TAC contents, suggesting that the type of by-product did not significantly influence their TAC levels. Notably, the methanolic fractions (EMB and EVB) demonstrated superior free radical scavenging activity across various in vitro mechanisms, which is closely related to their higher TAC concentrations. Chromatographic separation followed by MS analysis revealed common features in the molasses and vinasses samples, including a significant presence of PCs such as p-coumaric acid, schaftoside, chlorogenic acid, and feruloylquinic acid in the methanolic extracts (EMB and EVB); whereas the aqueous extracts (EMA and EVA) prominently featured DDMP as one of the most prevalent HICs.

Overall, the results of this study suggest that the antioxidant responses observed in molasses and vinasses extracts are related to the diverse natural compounds derived from the secondary metabolism of sugarcane, as well as various compounds formed during its industrial processing. The coexistence of PCs and HICs in these by-products may enhance their antioxidant properties due to the contribution of distinct but complementary mechanisms, potentially leading to additive or even synergistic biological responses. This functional interaction reinforces the value of sugarcane molasses and vinasses as promising materials for obtaining bioactive compounds that could support innovation in the development of bioactive materials. Such relevance aligns with current trends in waste valorization, indicating that these by-products may serve as sources of effective agents with notable potential in sustainable bioproduct design. Accordingly, it is crucial to explore whether these antioxidant properties are associated with additional biological activities related to oxidative stress regulation, such as cell proliferation inhibition. Investigating these connections could open new avenues for future health-related and pharmacological applications, including the development of targeted therapies for chronic diseases like cancer. Future studies should aim to elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which these compounds exert their bioactivity, particularly those associated with oxidative stress pathways and the regulation of cell proliferation. Gaining such insights is essential for translating the antioxidant potential of sugarcane molasses and vinasses into practical and therapeutically relevant applications, and fully leveraging their value in the development of bioactive materials. These research directions are currently being pursued in complementary studies derived from this investigation.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sarker, A. et al. A comprehensive review of food waste valorization for the sustainable management of global food waste. Sustain. Food Technol. 2, 48–69 (2024).

Roy, P., Mohanty, A. K., Dick, P. & Misra, M. A review on the challenges and choices for food waste valorization: Environmental and economic impacts. ACS Environ. Au 3, 58–75 (2023).

da Silva Souza, E. G. & Rebelato, M. G. Assessment of the environmental performance of sugarcane companies based on waste disposed of on the soil. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 22, 123–137 (2023).

Raza, Q. U. A. et al. Sugarcane industrial byproducts as challenges to environmental safety and their remedies: A review. Water (Basel) 13, 3495 (2021).

Stephen, G. S., Shitindi, M. J., Bura, M. D., Kahangwa, C. A. & Nassary, E. K. Harnessing the potential of sugarcane-based liquid byproducts: Molasses and spentwash (vinasse) for enhanced soil health and environmental quality. A systematic review. Front. Agron. 6, 1358076 (2024).

Mordenti, A. L., Giaretta, E., Campidonico, L., Parazza, P. & Formigoni, A. A review regarding the use of molasses in animal nutrition. Animals 11, 115 (2021).

Moran-Salazar, R. G. et al. Utilization of vinasses as soil amendment: Consequences and perspectives. Springerplus 5, 1007 (2016).

Molina-Cortés, A., Quimbaya, M., Toro-Gomez, A. & Tobar-Tosse, F. Bioactive compounds as an alternative for the sugarcane industry: Towards an integrative approach. Heliyon 9, e13276 (2023).

Ungureanu, N., Vlăduț, V. & Biriș, S. Ș. Sustainable valorization of waste and by-products from sugarcane processing. Sustainability 14, 11089 (2022).

Eggleston, G. & Lima, I. Sustainability issues and opportunities in the sugar and sugar-bioproduct industries. Sustainability 7, 12209–12235 (2015).

Kumar, K., Debnath, P., Singh, S. & Kumar, N. An overview of plant phenolics and their involvement in abiotic stress tolerance. Stresses 3, 570–585 (2023).

Karthikeyam, J. & Samipillai, S. S. Sugarcane in therapeutics. J. Herb. Med. Toxicol. 4, 9–14 (2010).

Singh, A. et al. Phytochemical profile of sugarcane and its potential health aspects. Pharmacog. Rev. 9, 45 (2015).

Khare, C. P. Indian Medicinal Plants. An Illustrated Dictionary (Springer, 2007).

Liu, X. et al. Maillard conjugates and their potential in food and nutritional industries: A review. Food Front. 1, 382–397 (2020).

Kathuria, D., Gautam, S. & Thakur, A. Maillard reaction in different food products: Effect on product quality, human health and mitigation strategies. Food Control 153, 109911 (2023).

Yu, X., Zhao, M., Liu, F., Zeng, S. & Hu, J. Identification of 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one as a strong antioxidant in glucose-histidine Maillard reaction products. Food Res. Int. 51, 397–403 (2013).

Yu, X., Zhao, M., Liu, F., Zeng, S. & Hu, J. Antioxidants in volatile Maillard reaction products: Identification and interaction. LWT 53, 22–28 (2013).

Hwang, I. G., Kim, H. Y., Woo, K. S., Lee, J. & Jeong, H. S. Biological activities of Maillard reaction products (MRPs) in a sugar-amino acid model system. Food Chem. 126, 221–227 (2011).

Hwang, I. G. et al. Isolation and identification of an antioxidant substance from heated garlic (Allium sativum L.). Food Sci. Biotechnol. 16, 963–966 (2007).

Liu, H. et al. Influence of canning and storage on physicochemical properties, antioxidant properties, and bioactive compounds of apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) wholes, halves, and pulp. Front. Nutr. 1, 850730 (2022).

Martini, S., Conte, A., Cattivelli, A. & Tagliazucchi, D. Domestic cooking methods affect the stability and bioaccessibility of dark purple eggplant (Solanum melongena) phenolic compounds. Food Chem. 341, 128298 (2021).

Madrau, M. A., Sanguinetti, A. M., Del Caro, A., Fadda, C. & Piga, A. Contribution of melanoidins to the antioxidant activity of prunes. J. Food Qual. 33, 155–170 (2010).

Caderby, E. et al. Sugar cane stillage: A potential source of natural antioxidants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 61, 11494–11501 (2013).

Martinez-Gomez, A., Caballero, I. & Blanco, C. A. Phenols and melanoidins as natural antioxidants in beer. Structure, reactivity and antioxidant activity. Biomolecules 10, 400 (2020).

Payet, B., Sing, A. S. C. & Smadja, J. Comparison of the concentrations of phenolic constituents in cane sugar manufacturing products with their antioxidant activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 54, 7270–7276 (2006).

Guimarães, C. M. et al. Antioxidant activity of sugar molasses, including protective effect against DNA oxidative damage. J. Food Sci. 72, 39–43 (2007).

Molina-Cortés, A., Sánchez-Motta, T., Tobar-Tosse, F. & Quimbaya, M. Spectrophotometric estimation of total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of molasses and vinasses generated from the sugarcane industry. Waste Biomass Valor. 11, 3453–3463 (2020).

Centro de Investigación de la Caña de Azúcar de Colombia (Cenicaña). Estandarización de Los Sistemas de Medición En Los Ingenios Azucareros de Colombia. Manual de Laboratorio - Volumen 1: Procedimientos Analíticos. (Cali, Colombia, 1996).

Michalkiewicz, A., Biesaga, M. & Pyrzynska, K. Solid-phase extraction procedure for determination of phenolic acids and some flavonols in honey. J. Chromatogr. A 1187, 18–24 (2008).

Pascual-Maté, A., Osés, S. M., Fernández-Muiño, M. A. & Sancho, M. T. Analysis of polyphenols in honey: Extraction, separation and quantification procedures. Sep. Purif. Rev. 47, 142–158 (2018).

Singleton, V. L., Orthofer, R. & Lamuela-Raventós, R. M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol 299, 152–178 (1999).

del Sánchez-Camargo, A. P. et al. Microwave-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds with antioxidant and anti-proliferative activities from supercritical CO2 pre-extracted mango peel as valorization strategy. LWT 137, 110414 (2021).

Brand-Williams, W., Cuvelier, M. E. & Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT 28, 25–30 (1995).

Valli, V. et al. Sugar cane and sugar beet molasses, antioxidant-rich alternatives to refined sugar. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60, 12508–12515 (2012).

Sonkawade, S. D. & Naik, G. R. In vitro evaluation of antioxidant properties of sugarcane extracts rich in dietary nucleotides. Int. J. Adv. Biol. Res. 5, 243–250 (2015).

Abbas, S. R., Sabir, S. M., Ahmad, S. D., Boligon, A. A. & Athayde, M. L. Phenolic profile, antioxidant potential and DNA damage protecting activity of sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum). Food Chem. 147, 10–16 (2014).

Re, R. et al. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 26, 1231–1237 (1999).

Payet, B., Sing, A. S. C. & Smadja, J. Assessment of antioxidant activity of cane brown sugars by ABTS and DPPH radical scavenging assays: Determination of their polyphenolic and volatile constituents. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 10074–10079 (2005).

Dong, J. W., Cai, L., Xing, Y., Yu, J. & Ding, Z. T. Re-evaluation of ABTS·+ assay for total antioxidant capacity of natural products. Nat. Prod. Commun. 10, 2169–2172 (2015).

Benzie, I. F. F. & Strain, J. J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of ‘antioxidant power’: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 239, 70–76 (1996).

Benzie, I. F. F. & Strain, J. J. Ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay: Direct measure of total antioxidant activity of biological fluids and modified version for simultaneous measurement of total antioxidant power and ascorbic acid concentration. Methods Enzymol. 299, 15–27 (1999).

Pulido, R., Bravo, L. & Saura-Calixto, F. Antioxidant activity of dietary polyphenols as determined by a modified ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48, 3396–3402 (2000).

Rajurkar, N. S. & Hande, S. M. Estimation of phytochemical content and antioxidant activity of some selected traditional Indian medicinal plants. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 73, 146 (2011).

Kong, F., Yu, S., Zeng, F. & Wu, X. Preparation of antioxidant and evaluation of the antioxidant activities of antioxidants extracted from sugarcane products. J. Food Nutr. Res. 3, 458–463 (2015).

Ballesteros-Vivas, D., Alvarez-Rivera, G., Ibánez, E., Parada-Alfonso, F. & Cifuentes, A. Integrated strategy for the extraction and profiling of bioactive metabolites from Passiflora mollissima seeds combining pressurized-liquid extraction and gas/liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 1595, 144–157 (2019).

Rodrigues Reis, C. E. & Hu, B. Vinasse from sugarcane ethanol production: Better treatment or better utilization?. Front. Energy Res. 5, 1–7 (2017).

Acosta-Cárdenas, A., Alcaraz-Zapata, W. & Cardona-Betancur, M. Sugarcane molasses and vinasse as a substrate for polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) production. Dyna (Medellin) 85, 220–225 (2018).

Ahmed, O., Sulieman, A. M. E. & Elhardallou, S. B. Physicochemical, chemical and microbiological characteristics of vinasse, a by-product from ethanol industry. Am. J. Biochem. 3, 80–83 (2013).

Instituto Colombiano de Normas Técnicas y Certificación (ICONTEC). Norma Técnica Colombiana NTC 587 - Industrias Alimentarias e Industrias de Bebidas. Melaza de Caña. (Instituto Colombiano de Normas Técnicas y Certificación (ICONTEC), Bogotá (Colombia), 1994).

Aristizábal, C. Caracterización físico-química de una vinaza resultante de la producción de alcohol de una industria licorera, a partir del aprovechamiento de la caña de azúcar. Revista de Ingenierías USBMED 6, 36–41 (2015).

Quintero-Dallos, V. et al. Vinasse as a sustainable medium for the production of Chlorella vulgaris UTEX 1803. Water (Basel) 11, 1526 (2019).

Bunzel, M. & Schenderl, R. R. Determination of (total) phenolics and antioxidant capacity in food and ingredients. in Food Analysis 455–468 (Springer, 2017).

Duarte-Almeida, J. M., Salatino, A., Genovese, M. I. & Lajolo, F. M. Phenolic composition and antioxidant activity of culms and sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) products. Food Chem. 125, 660–664 (2011).

Takara, K., Matsui, D., Wada, K., Ichiba, T. & Nakasone, Y. New antioxidative phenolic glycosides isolated from Kokuto non-centrifuged cane sugar. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 66, 29–35 (2002).

Jaffé, W. R. Nutritional and functional components of non centrifugal cane sugar: A compilation of the data from the analytical literature. J. Food Compos. Anal. 43, 194–202 (2015).

Deng, Q., Penner, M. H. & Zhao, Y. Chemical composition of dietary fiber and polyphenols of five different varieties of wine grape pomace skins. Food Res. Int. 44, 2712–2720 (2011).

Babbar, N., Oberoi, H. S., Uppal, D. S. & Patil, R. T. Total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of extracts obtained from six important fruit residues. Food Res. Int. 44, 391–396 (2011).

Babbar, N., SinghOberoi, H., KaurSandhu, S. & KumarBhargav, V. Influence of different solvents in extraction of phenolic compounds from vegetable residues and their evaluation as natural sources of antioxidants. J. Food Sci. Technol. 51, 2568–2575 (2014).

Munir, A. et al. Evaluation of antioxidant potential of vegetables waste. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 27, 947–952 (2018).

Cerretani, L. & Bendini, A. Rapid assays to evaluate the antioxidant capacity of phenols in virgin olive oil. in Olives and Olive Oil in Health and Disease Prevention (Elsevier, 2010).

Lee, K. J., Oh, Y. C., Cho, W. K. & Ma, J. Y. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity determination of one hundred kinds of pure chemical compounds using offline and online screening HPLC assay. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015, 1–13 (2015).

Ali, S., El Gedaily, R., Mocan, A., Farag, M. & El-Seedi, H. Profiling metabolites and biological activities of sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum Linn.) juice and its product molasses via a multiplex metabolomics approach. Molecules 24, 934 (2019).

Colombo, R., Yariwake, J. H., Queiroz, E. F., Ndjoko, K. & Hostettmann, K. On-line identification of further flavone C- and O-glycosides from sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L., Gramineae) by HPLC-UV-MS. Phytochem. Anal. 17, 337–343 (2006).

Deseo, M. A., Elkins, A., Rochfort, S. & Kitchen, B. Antioxidant activity and polyphenol composition of sugarcane molasses extract. Food Chem. 314, 126180 (2020).

Chen, J. et al. Structure-antioxidant activity relationship of methoxy, phenolic hydroxyl, and carboxylic acid groups of phenolic acids. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–9 (2020).

Balasundram, N., Sundram, K. & Samman, S. Phenolic compounds in plants and agri-industrial by-products: Antioxidant activity, occurrence, and potential uses. Food Chem. 99, 191–203 (2006).

Morita, K., Arimochi, H. & Ohnishi, Y. In vitro cytotoxicity of 4-methylcatechol in murine tumor cells: Induction of apoptotic cell death by extracellular pro-oxidant action. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 306, 317–323 (2003).

Li, C. J. et al. 4-Methylcatechol inhibits cell growth and testosterone production in TM3 Leydig cells by reducing mitochondrial activity. Andrologia 49, e12581 (2017).

Payton, F., Bose, R., Alworth, W. L., Kumar, A. P. & Ghosh, R. 4-Methylcatechol-induced oxidative stress induces intrinsic apoptotic pathway in metastatic melanoma cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 81, 1211–1218 (2011).

Jeong, J. B., Hong, S. C., Jeong, H. J. & Koo, J. S. Anti-inflammatory effect of 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol via the suppression of NF-κB and MAPK activation, and acetylation of histone H3. Arch. Pharm. Res. 34, 2109–2116 (2011).

Kim, D. H. et al. 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol attenuates migration of human pancreatic cancer cells via blockade of FAK and AKT signaling. Anticancer Res. 39, 6685–6691 (2019).

Jeong, J. B. & Jeong, J. 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol can induce cell cycle arrest by blocking the hyper-phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein in benzo[a]pyrene-treated NIH3T3 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 400, 752–757 (2010).

Asami, E., Kitami, M., Ida, T., Kobayashi, T. & Saeki, M. Anti-inflammatory activity of 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol involves inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced inducible nitric oxidase synthase by heme oxygenase-1. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 45(5), 589–596 (2023).

Kuwahara, H. et al. Antioxidative and antimutagenic activities of 4-vinyl-2,6-dimethoxyphenol (canolol) isolated from canola oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 52, 4380–4387 (2004).

Shrestha, K., Stevens, C. V. & De Meulenaer, B. Isolation and identification of a potent radical scavenger (canolol) from roasted high erucic mustard seed oil from nepal and its formation during roasting. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60, 7506–7512 (2012).

Fagbemi, K. O. et al. Bioactive compounds, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of methanol extract of Tamarindus indica Linn. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–12 (2022).

Kjällstrand, J. & Petersson, G. Phenolic antioxidants in wood smoke. Sci. Total Environ. 277, 69–75 (2001).

Wang, L. et al. Comparative analyses of three sterilization processes on volatile compounds in sugarcane juice. Trans. ASABE 62, 1689–1696 (2019).

Chen, E. et al. Comparison of odor compounds of brown sugar, muscovado sugar, and brown granulated sugar using GC-O-MS. LWT 142, 111002 (2021).

Ge, Y. et al. Formation of volatile and aroma compounds during the dehydration of membrane-clarified sugarcane juice to non-centrifugal sugar. Foods 10, 1561 (2021).

Okutsu, K. et al. Characterization of aroma profiles of kokuto-shochu prepared from three different cultivars of sugarcane. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 135, 458–465 (2023).

Silva, P., Freitas, J., Nunes, F. M. & Câmara, J. S. Effect of processing and storage on the volatile profile of sugarcane honey: A 4-year study. Food Chem. 365, 130457 (2021).

Kaushik, A., Basu, S., Batra, V. S. & Balakrishnan, M. Fractionation of sugarcane molasses distillery wastewater and evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial characteristics. Ind. Crops Prod. 118, 73–80 (2018).

Fagier, M. A., Elmugdad, A. A., Aziz, M. E. A. & Gabra, N. M. Identification of some organic compounds in sugarcane vinasse by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and prediction of their toxicity using TEST method. J. Chem. Pharm. Sci. 8, 899–905 (2015).

Yang, X. Z. & Yu, A. N. Aroma compounds generated from L-ascorbic acid and L-methionine during the Maillard reaction. Adv. Mat. Res. 781–784, 1811–1817 (2013).

Osada, Y. & Shibamoto, T. Antioxidative activity of volatile extracts from Maillard model systems. Food Chem. 98, 522–528 (2006).

Kitts, D. D., Chen, X. M. & Jing, H. Demonstration of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory bioactivities from sugar-amino acid Maillard reaction products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60, 6718–6727 (2012).

Mu, K., Wang, S. & Kitts, D. D. Evidence to indicate that Maillard reaction products can provide selective antimicrobial activity. Integr. Food Nutr. Metab. 3, 330–335 (2016).

Coghe, S., Derdelinckx, G. & Delvaux, F. R. Effect of non-enzymatic browning on flavour, colour and antioxidative activity of dark specialty malts - A review. Monatsschr. Brauwiss. 57, 25–38 (2004).

Lakshmanan, C. M. & Hoelscher, H. E. Production of levoglucosan by pyrolysis of carbohydrates. Ind. Eng. Chem. Prod. Res. Develop. 9, 57–59 (1970).

Effendi, A., Gerhauser, H. & Bridgwater, A. V. Production of renewable phenolic resins by thermochemical conversion of biomass: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 12, 2092–2116 (2008).

Santos-Sánchez, N. F., Salas-Coronado, R., Villanueva-Cañongo, C. & Hernández-Carlos, B. Antioxidant compounds and their antioxidant mechanism. in Antioxidants (IntechOpen, 2019).

Al-Mamary, M. A., Moussa, Z., Al-Mamary, M. A. & Moussa, Z. Antioxidant activity: The presence and impact of hydroxyl groups in small molecules of natural and synthetic origin. in Antioxidants (IntechOpen, 2021).

Nahar, P. P., Driscoll, M. V., Li, L., Slitt, A. L. & Seeram, N. P. Phenolic mediated anti-inflammatory properties of a maple syrup extract in RAW 264.7 murine macrophages. J. Funct. Foods 6, 126–136 (2014).

Langner, E. et al. Melanoidins isolated from heated potato fiber (Potex) affect human colon cancer cells growth via modulation of cell cycle and proliferation regulatory proteins. Food Chem. Toxicol. 57, 246–255 (2013).

Swaran, J. S. & Structural, F. chemical and biological aspects of antioxidants for strategies against metal and metalloid exposure. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2, 191–206 (2009).

Dai, J. & Mumper, R. J. Plant phenolics: Extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules 15, 7313 (2010).

Parcheta, M. et al. Recent developments in effective antioxidants: The structure and antioxidant properties. Materials 14, 1984 (2021).

Nooshkam, M. & Varidi, M. Antioxidant and antibrowning properties of Maillard reaction products in food and biological systems. Vitam. Horm. 125, 367–399 (2024).

Toydemir, G. et al. Effect of food processing on antioxidants, their bioavailability and potential relevance to human health. Food Chem. X 14, 100334 (2022).

Cezarotto, V. S. et al. Influence of harvest season and cultivar on the variation of phenolic compounds composition and antioxidant properties in Vaccinium ashei leaves. Molecules 22, 1603 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Colombian Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MINCIENCIAS) through the Research Grant 808—Project ID: 125180864199, and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MICINN/AEI, Spain) through the projects PID2020-113050RB-I00, PDC2021-120814-I00, and EQC2021-007112-P. The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript. The authors express their gratitude to the Sugarcane Research Center of Colombia (Centro de Investigación de la Caña de Azúcar de Colombia—Cenicaña) for their assistance in obtaining the molasses and vinasse samples analyzed in this study. G. Alvarez-Rivera would like to acknowledge MICINN/AEI for the IJC2019-041482-I and RYC2022-037949-I postdoctoral contracts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A. Molina-Cortés: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—Original draft. F. Tobar-Tosse: Supervision, Project administration, Writing—Review and editing. M. Quimbaya: Supervision, Project administration, Writing—Review and editing. G. Álvarez-Rivera: Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—Review and editing. A. Cifuentes: Supervision, Resources, Writing—Review and editing. A. Jaramillo-Botero: Supervision, Writing—Review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Molina-Cortés, A., Tobar-Tosse, F., Quimbaya, M. et al. Study of two sugarcane by-products as source of secondary metabolites and heat-induced compounds with potential bioactive applications. Sci Rep 15, 19788 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03262-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03262-7