Abstract

The hierarchical analysis of user needs, function mapping, and the intelligent extraction and matching of related product patent technical features are crucial for seeking innovative design solutions and improving design efficiency. Patent documents contain rich technical features that provide valuable technical references and innovative inspiration for product development. However, the complexity of patent documents and the variability in their textual descriptions make it difficult for designers to utilize patents for technological innovation. To address this issue, this research proposes an integrated method for requirement mining and classification, requirement-function mapping, and intelligent matching of functions with patent technical features, thereby achieving effective mappings between requirements, functions, and technical features. The method consists of four main steps: First, based on the Kano model, this research proposes a G-HOQ method for requirement mining, classification, and function mapping, integrating Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) and the House of Quality (HOQ). This method addresses the issue of reducing decision subjectivity and accurately mining user needs under small sample conditions. Second, based on the characteristics of patent texts, an N-V-N structure (noun-verb-noun) is constructed, and Natural Language Processing (NLP) technology is used to extract patent technical features. Third, the BERT model and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) are applied for vector transformation and dimensionality reduction of feature texts, completing the digital characterization. Fourth, the cosine similarity algorithm is used to identify the required functional needs from patent technical documents and to reorganize solutions based on actual requirements, thereby promoting design innovation. Finally, an innovative design for an earthquake experience platform was used as an example, and four design schemes were developed. The satisfaction of the schemes was evaluated using the fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method, revealing that Scheme A, derived from the proposed method, had the shortest time and the highest overall score of 3.287, thus validating the feasibility and effectiveness of the method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Accurately understanding user needs, effectively utilizing technical knowledge, and efficiently outputting design solutions are key factors in the competitive landscape of modern product innovation1,2. In the design innovation process, from the exploration of emotional needs to the generation of technical solutions, it typically relies on designers’ initial understanding of the task and their re-integration and application of knowledge within their own cognitive scope3. Due to differences in individual knowledge and experience, designers face issues of subjectivity, inefficiency, and limitations when understanding and selecting from vast technical documentation4. The introduction of an intelligent design method, from requirement mining to function mapping and technical feature matching, is of significant importance for design models that derive and acquire technological innovation solutions based on users’ emotional needs5. Therefore, to obtain innovative design solutions in a more objective and efficient manner, many scholars have explored areas such as user needs, function mapping, intelligent design, text mining, and digitization. For instance, Fu et al. proposed a product concept design method driven by the Function-Behavior-Structure (FBS) model. This method optimizes concept design solutions by establishing a mapping matrix and integrating evaluation criteria, thereby improving design efficiency and solution quality6. Lou et al. developed a memory-heuristic reinforcement learning framework based on Function-Behavior (F-B) mapping. By employing Markov decision processes and motivation-driven learning, they formalized the F-B mapping and learned knowledge from historical design cases, enabling self-learning and self-evolution of design knowledge, thus enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of concept design7. The above achievements aim to utilize a hierarchical mapping approach to transform vague conceptual design problems from abstract to concrete structures, establishing a mapping mechanism between design concepts and product structures. Furthermore, in terms of understanding requirement intentions, Hao et al. proposed a product modularization method based on requirement analysis, design mapping, and solution implementation to accommodate the diversification of user needs and cognitive differences8. Sun et al. proposed the CM-Kano model for the dynamic analysis of customer and manufacturer opinions9. Lee et al. introduced a Kano requirement analysis method that integrates industry context10. Many scholars have also integrated theoretical methods such as Kano, QFD, and TRIZ into requirement mining, function mapping, and design innovation11,12,13,14. These methods effectively address the issues of mapping requirements to functional structures and resolving conflicts between functions. However, they still face limitations in terms of design efficiency, intelligence, and the innovative use of existing technical knowledge, lacking systematic approaches.

In recent years, with the rapid development of artificial intelligence technologies, intelligent design methods have gradually been applied in design innovation activities, such as those driven by experience and review data15,16, knowledge graphs, and graph neural networks17,18. In the field of knowledge text mining, extracting technical features from patent documents is crucial for design innovation and the analysis of technological development trends. Patent databases contain over 90% of the world’s technical features, covering functional knowledge across various fields19,20. Leveraging natural language processing (NLP) technologies, scholars have developed methods to support intelligent innovation design. For instance, Zhang et al. proposed an intelligent innovation design model that integrates function coding, patent text feature extraction, digital representation, and image similarity matching. This method significantly improves the efficiency of design innovation and facilitates the effective use of technical knowledge21. Furthermore, research on technological knowledge mining often focuses on analyzing and predicting technological development trends and opportunities within specific fields. For example, Yun et al. employed patent semantic mining to identify the technological evolution patterns in target fields, aiding in the identification of new technological opportunities22.Han et al., based on the Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) model and using patent texts as data, proposed a method for industry-level research and development trend analysis23. Yuan et al. utilized natural language processing (NLP) technologies to analyze patent literature, revealing the development progress and opportunities in solid-state battery technology through the construction of a Patent Information Relationship Matrix (IRM)24.

Although the aforementioned studies utilized artificial intelligence technologies to extract and analyze text features, there is still a lack of research on the intelligent mining, visualization, and adaptation of technical features in innovative design. Existing design methods lack systematization, with most studies focusing on only specific stages of the design process, leading to issues such as disconnected data and processes in design analysis. In modern product design innovation practices, designers still rely on experience and subjective judgment to sift through large volumes of technical literature, which is inefficient and limited in scope. Therefore, this research combines tools such as the Kano model25, Quality Function Deployment (QFD)26, Grey Relational Analysis (GRA)27, Natural Language Processing (NLP), and image similarity matching algorithms28, proposing an innovative design method based on requirement analysis, integrating function mapping and coding, and technical feature mining and digital matching. This method provides a more systematic and intelligent solution to the design process, aiming to enhance both the efficiency and quality of design.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows.

-

This research proposes an innovative product design method that integrates user requirement analysis, function mapping, function coding, patent technical feature extraction and visualization, and similarity matching. Compared to traditional design methods, this approach offers a more comprehensive process, covering the critical stages of product innovation design, from requirements to functions to technical solutions, thereby improving the efficiency and intelligence of design and R&D.

-

This research integrates the Kano model, Grey Relational Analysis (GRA), and the House of Quality (HOQ), proposing a G-HOQ functional requirement analysis method that associates and ranks the importance of requirements and technical features. The integrated method reduces the interference of subjective factors in small-sample studies and offers the advantages of accurately and quickly understanding user needs and forming product technical solutions.

-

The research constructs an N-V-N structure and, based on Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques, the BERT model, Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and cosine similarity algorithms, proposes an innovative design method for intelligent extraction, visualization, and matching of patent technical features. This method enables the rapid and efficient identification of technical features from patent documents that meet product functional requirements. The method effectively reduces issues such as the reliance on designers’ personal experience for subjective judgment, limited coverage in technical document screening, and low efficiency, enhancing the efficiency of design innovation and the intelligent level of product technical solution design.

The overall structure of this paper is as follows.

The second section systematically introduces the method for digital representation and matching of functional requirements to technical features for product innovation design. The third section provides a step-by-step analysis and validation of the proposed method through a case study of the innovative design of an earthquake experience platform. The fourth section implements the design schemes based on the experimental results from the third section and evaluates the design outcomes. The fifth section discusses the research findings and provides an outlook for future work. The sixth section summarizes the entire paper.

Methods

Participants

This study collected data through interviews and questionnaires, focusing on four main aspects: (1) During the initial stage of collecting user requirements for the earthquake experience platform, a total of 92 questionnaires were collected, with participants aged between 18 and 45, and a gender distribution of 53.3% male and 46.7% female. (2) In the requirement classification phase, 112 Kano questionnaires were distributed. After excluding invalid or incomplete responses, 100 valid questionnaires were returned, yielding a response rate of 89.3%. Among the valid responses, 53 were from males and 47 from females, with ages also ranging from 18 to 45. (3) In the phase of analyzing the correlation between technical features and requirements and determining their implementation importance, 15 design professionals were invited to conduct technical feature analysis and importance assessment. The experts had an average of 9 years of professional experience and came from 8 companies and 2 universities. Their ages ranged from 38 to 56, with 9 males and 6 females. (4) In the solution evaluation phase, 63 participants were invited, including 26 design professionals (9 frontline designers and 17 university faculty members and students), and 46 users. Participants’ ages ranged from 20 to 55, with 34 males and 29 females. All experimental procedures adhered to relevant ethical guidelines and regulations. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Mechanical and Precision Instrument Engineering at Xi’an University of Technology.

This section will systematically introduce the theoretical methods related to requirement mining and functional mapping, functional feature encoding and digital representation, as well as the matching of functional requirements with patent technical features.

Method flow overview

To address the issues of inconsistent hierarchical mapping of design knowledge, irregular expression of functional knowledge, and low design efficiency in product innovation design based on user requirements and patent technology, a method for the digital representation and identification of functions in intelligent product design is proposed. Using this method, designers can classify and filter affective requirements, map functions, retrieve relevant patent literature based on functional needs, and perform digital representation. By using an image similarity algorithm to identify similar functional knowledge, this method not only enhances design efficiency but also reduces the workload of designers, achieving intelligent and innovative product design.

The process flow of the method for the digital representation and identification of functional features based on user requirements and patent technology is shown in Fig. 1.

The method flow steps are summarized as follows.

Step 1: Requirement Analysis and Function Mapping. Product requirements are extensively collected through surveys, interviews, market research, and other methods. Kano is used for requirement classification and filtering, QFD is employed to map requirements to functional needs, and a Grey Relational Matrix is constructed. This ensures that the product design functions accurately meet user needs. The specific process and methods are detailed in Sect. 2.2.

Step 2: Construct the G-HOQ (House of Quality) for functional requirements. The importance of functional features is calculated and ranked to comprehensively assess and identify the functional characteristics that have the greatest impact on customer satisfaction and product performance.

Step 3: Function Feature Encoding and Extraction. An N-V-N encoding rule is established to retrieve relevant patent literature in the field. NLP techniques are then used for function feature extraction, creating an N-V-N database containing both patent technologies and functional requirement features. The specific process is detailed in Sect. 2.3. This approach creates a database that not only deepens the understanding of existing technologies but also supports functional innovation in new product designs, enabling design teams to effectively utilize existing technical data and accelerate the product development process.

Step 4: Digital Representation of Function Features. Following the method outlined in Sect. 2.4, the digital representation of functional requirements and patent technology features is completed, providing the foundation for the subsequent step of similarity-based intelligent matching between functions and technical features.

Step 5: Similarity Matching of Function and Technical Features. This step enables the design team to quickly identify the best technical solutions that meet product requirements, thereby enhancing both design efficiency and innovation. Moreover, similarity matching promotes the integration of cross-domain technologies, bringing more innovative possibilities to product development. The specific process is detailed in Sect. 2.5.

Step 6: Function Feature Reorganization and Innovative Design. Based on the matched technical features and incorporating practical design considerations, designers reorganize function features to create feasible and innovative solutions, thus achieving flexibility and personalization in design innovation.

Requirement analysis and function mapping

User requirements determine the goals of design innovation29. Due to the subjective nature of user needs, failure to properly distinguish and analyze them may lead to design failure30. Therefore, it is crucial to scientifically classify, filter, and map these requirements into functions. The Kano model, proposed by Japanese scholar Noriaki Kano, identifies and classifies user needs by investigating the impact of product attributes on customer satisfaction31. It categorizes a wide range of raw needs into basic (M), expected (O), excitement (A), and indifferent (I) needs. The Kano model helps designers prioritize satisfying users’ fundamental needs while uncovering their expectations and excitements, thus enhancing the product’s competitiveness. This section will apply the Kano model to analyze user needs, and use QFD in combination with GRA to perform functional mapping and importance ranking of the needs.

The basic steps of the user needs and functional mapping method are as follows:

-

1

Requirement acquisition and analysis. User needs are extensively collected through user interviews and market feedback, and KANO questionnaires are created and distributed. The Better-Worse coefficients are calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2), where Better (satisfaction impact) and Worse (dissatisfaction impact) are used to determine the sensitivity of user needs. The Better coefficient ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater sensitivity and higher priority, while the Worse coefficient ranges from − 1 to 0, with lower values indicating greater sensitivity and higher priority. Where: A represents Excitement needs, M represents Basic needs, O represents Expectation needs, and I represents Indifferent needs.

-

2

Demand Classification and Selection. A Better-Worse coefficient chart is drawn to classify the demands. Basic needs (M) are the minimum requirements of users and must be prioritized. Expectation needs (O) are key factors that influence user satisfaction and should be fulfilled as much as possible. Excitement needs (A) provide additional value beyond user expectations, which can enhance user loyalty. Indifferent needs (I) are those that do not affect user satisfaction, whether present or absent, and should be eliminated. In the Better-Worse coefficient diagram, the first quadrant indicates that when the product offers this feature, user satisfaction will increase; when this feature is not provided, user satisfaction will decrease. The second quadrant indicates that when the feature is not provided, user satisfaction will not decrease, but when the feature is provided, user satisfaction will significantly improve. The third quadrant represents features where user satisfaction will not change whether the feature is provided or not; these are features that users do not care about. The fourth quadrant indicates that when the product offers this feature, user satisfaction will not improve; however, when this feature is not provided, user satisfaction will decrease significantly. This suggests that features in this quadrant are the most basic requirements. Therefore, in the demand selection process, it is necessary to eliminate indifferent needs in the third quadrant. Efforts should be focused on meeting the basic user needs, which are the essential factors represented in the fourth quadrant, followed by addressing the user’s expected needs, which are the expected factors represented in the first quadrant. These are competitive quality factors that differentiate the product and service from competitors. Finally, aim to fulfill the user’s excitement needs, which are the excitement factors represented in the second quadrant, to enhance user loyalty.

-

3

Construct the Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) matrix between user requirements and functional features. Use the House of Quality (HOQ) in Quality Function Deployment (QFD) to convert customer needs into specific functional characteristics.Apply GRA to construct the importance correlation matrix between user requirements and functional features.Invite relevant professional designers to score user requirements and technical features separately, using a 1–9 scale for importance evaluation, where 1 is the least important and 9 is the most important, to obtain the user requirements and functional features evaluation table.

Let \(\:{\text{X}}_{0}=\left({\text{x}}_{\text{i}}\right(1),{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}(2),\cdots\:,{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}(\text{n}\left)\right)(\text{i}=\text{1,2},\cdots\:,\text{m})\) be the user requirement reference sequence, and \(\:{\text{X}}_{\text{i}}=\left({\text{x}}_{\text{i}}\right(1),{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}(2),\cdots\:,{\text{x}}_{\text{i}}(\text{n}\left)\right)(\text{i}=\text{1,2},\cdots\:,\text{m})\)the comparison sequence of technical features. Calculate the grey relational degree \(\:{{\upepsilon\:}}_{\text{i}}\left(\text{k}\right)\) between \(\:{\text{X}}_{0}\) and \(\:{\text{X}}_{\text{i}}\) using formula (3), thereby obtaining the grey relational matrix \(\:\text{G}\).

The grey relational degree between \(\:{X}_{0}\) and \(\:{X}_{i}\) is:

Where \(\:\rho\:\) is the distinguishing coefficient, with a value between \(\:0\le\:\rho\:\le\:1\), taken as 0.5;

(4) Construct the House of Quality (HOQ) for requirements and functional features. Fill the gray relational degree matrix into the HOQ, and use the traditional HOQ method32 combined with the gray relational degree matrix to calculate and rank the importance of technical features according to formula (5). Based on the ranking results, the focus of the design and the priority of functions are determined, providing a scientific basis for resource allocation, evaluation decisions, and meeting user needs.

Where: \(h_j\) is the importance of the \(\:j\)-th technical feature;

\(\:m\) is the total number of demand features;

\(\:{\epsilon}_{kj}\) is the gray relational degree between demand features and technical features (from the gray relational matrix);

\(\:{\text{X}}_{\text{k}}\) is the importance of the \(\:\text{k}\)-th demand feature;

\(\:\text{j}\) is the identifier of the technical feature;

\(\:\text{k}\) is the identifier of the demand feature.

Functional feature coding and extraction

Patent literature contains abundant technical knowledge. By identifying and matching the functional requirements in design with patents from the relevant research field, design teams can be provided with technical solutions, inspire innovation, facilitate the commercialization of patents33, and significantly enhance design efficiency. To address this, this section proposes a method for encoding and extracting functional features using natural language processing (NLP) technology, based on an N(Noun)-V(Verb)-N(Noun) structure. This method encodes functional features to clarify the expression of functional requirements, reduce textual ambiguity, and promote the standardized processing and classification of functional features, thereby providing a unified foundation for the subsequent automatic extraction and matching of functional features.

N-V-N functional feature coding

In the process of patent functional feature extraction, constructing structured and standardized coding rules can effectively capture the core semantic relationships of functional features. The study employs the N-V-N (Noun-Verb-Noun) structure for encoding, which consists of a noun-verb-noun sequence. In this structure, N (noun) represents the entity performing the action, typically the subject; V (verb) denotes the specific action or behavior executed by the subject, serving as the predicate; and the second N (noun) represents the object of the action, which is the target, or the object of the verb. This structure captures the relationship between the technical action and its subject and object through syntactic relationships, facilitating subsequent digital representation and matching of functions. For example, “slider (noun) pushes (verb) linkage (noun).”

In functional feature extraction, the dependency parsing module of the natural language processing tool spaCy is used to automatically locate the core verb and its dependency relations in the sentence, extracting the N-V-N structure. The specific implementation method is detailed in Sect. 2.3.2. This method efficiently extracts functional features from patent literature, providing high-quality input for subsequent digital representation and intelligent matching.

Patent technical feature extraction method

The process of automatically extracting functional components from patent corpus using NLP technology and constructing a functional feature set is as follows.

(1) Patent Text Acquisition and Organization. Use keyword search strategies combined with logical terms like “AND” and “OR” to retrieve patent sets from the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) database34. In patent technical documents, the invention content includes complete relationships between components and their actions35, which can serve as the raw corpus (\(\:T\)) for extracting N-V-N structural functional features. \(\:T\) serves as the input text, consisting of a series of sentences \(\:S=\{{S}_{1},{S}_{1},\cdots\:{S}_{n}\}\) each sentence \(\:{S}_{i}\) is composed of several words \(\:W=\{{w}_{1},{w}_{1},\cdots\:{w}_{m}\}\). Provide technical corpus support for subsequent analysis.

(2) Data preprocessing. The Chinese stop word list from Harbin Institute of Technology (HIT) is used to remove meaningless words from the input text. Additionally, regular expressions are employed to eliminate common ineffective phrases (e.g., “although,” “in conclusion”) and symbols (e.g., parentheses and numbers), resulting in a more standardized text input, denoted as \(\:T\). Use the spaCy tool for word segmentation and part-of-speech tagging to identify all verbs \(\:{V}_{i}\) in each sentence \(\:{S}_{i}\), forming a verb set \(\:{V}_{i}=\{{V}_{i1},{V}_{i2},\cdots\:{V}_{ik}\}\). For each verb \(\:{V}_{ik}\), identify the noun on its left as the subject \(\:{N}_{subj}\) and the noun on its right as the object \(\:{N}_{obj}\), resulting in noun pairs (\(\:{N}_{subj},{N}_{obj}\)).

(3) Dependency pParsing and N-V-N structure extraction. The spaCy dependency parsing model is used to identify the dependency relationships between words in a sentence and construct a syntactic dependency tree. The following rules are applied to extract the N-V-N structure: First, verbs (V) are located within the dependency tree; then, the subject (N) on the left side of the verb and the object (N) on the right side are matched. If both the subject and object exist, an N-V-N (Noun-Verb-Noun) phrase set is generated \(\:\text{N}\text{V}\text{N}\left(\text{T}\right)\). The N-V-N structure is represented as (\(\:{\text{N}}_{\text{s}\text{u}\text{b}\text{j}},{\text{V}}_{\text{i}\text{j}}\)), identifying the subject (Noun), action (Verb), and object (Noun) of the functional feature, resulting in an N-V-N structure set as shown in Eq. (5).

For the entire text \(\:\text{T}\), all its N-V-N structures are represented as \(\:NVN\left(T\right)\):

Where \(\:NVN\left(T\right)\) is the set of all N-V-N structures extracted from sentences \(\:{\text{S}}_{\text{i}}\):\(\:\:\:\:\:\:\:\;\;NVN\left( {{S_i}} \right) = \{ \left( {{N_{subj}}{V_{ij}}{N_{obj}}} \right)|{V_{ij}} \in {V_i}{N_{subj}} \in lefts\left( {{V_{ij}}} \right),{N_{obj}} \in rights\left( {{V_{ij}}} \right)\} \; \in \:rights\left( {{V_{ij}}} \right)\}\)

Where \(\:lefts\left({V}_{ij}\right)\) represents the noun dependent on the left side of the verb\(\:{V}_{ij}\), usually the subject; and \(\:\text{r}\text{i}\text{g}\text{h}\text{t}\text{s}\left({V}_{ij}\right)\) represents the noun dependent on the right side of the verb \(\:{V}_{ij}\), usually the object.

(4) Feature filtering and optimization. Since Chinese patent technical documents contain many specific terms such as “claim,” “described,” “a kind of,” “patent number,” etc., which have no substantive meaning in expressing functional features, regular expressions are used to filter out irrelevant or improperly formatted features to improve the quality and accuracy of \(\:NVN\left(T\right)\), forming the optimized technical feature set \(\:\text{F}\), as shown in formula (6).

Where \(\:\text{U}\)is the set of features to be filtered out,U={claim, described, a kind of, patent number, \(\:\cdots\:\)}.

\(\:f\) represents a single functional feature

Finally, the extracted standardized and structured functional features are stored in a new Word document, providing the foundation for subsequent feature matching.

Digital representation of functional features

Using NLP and machine learning techniques, unstructured patent texts are transformed into structured, digital feature vectors, enabling automatic matching of patent technologies and providing intelligent support for design innovation. The specific implementation methods and steps are as follows:

Vectorization of functional features in patent texts. The BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) model, developed by the Google AI Language team, is a pre-trained language model. The extracted functional feature \(\:f\) from the patent text is converted into a 768-dimensional feature vector. The BERT model is pre-trained on large-scale corpora, with its core component being the self-attention mechanism, which captures contextual information of words and generates vector representations36.

The vectorization process using the BERT model is as follows:

First, tokenize the input patent functional feature text \(\:f\) and add the \(\:\left[CLS\right]\) and \(\:\left[SEP\right]\) tokens to form the input sequence.

Next, use the BERT model to encode the input sequence \(\:\text{f}\), obtaining the hidden state matrix \(\:X\):

Where \(\:X\in\:{R}^{n\times\:d}\), \(\:\text{n}\) represents the length of the input sequence, and \(\:\text{d}\) is the dimension of the feature vector, \(\:d=768\), which is the dimension of the BERT model’s hidden layer. \(\:\text{B}\text{E}\text{R}\text{T}\left(\text{s}\right)\) denotes the encoding process of the input text \(\:\text{f}\) by the pre-trained BERT model.

Finally, extract the vector at the \(\:\left[GLS\right]\) token position from the hidden state matrix \(\:X\) as the feature vector of the input text \(\:{x}_{CLS}^{bert}\):

Where,\(\:{x}_{CLS}^{bert}\in\:{R}^{768}\)

(2) Dimensionality Reduction of Functional Feature Vectors. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is applied to reduce the dimensionality of the data, providing a foundation for subsequent digital representation. PCA projects high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space through linear transformation, minimizing information loss. The study uses a Cumulative Explained Variance Plot to determine the number of principal components, ensuring that the selected components explain more than 95% of the variance while retaining as much information as possible. The dimensionality-reduced feature vectors not only reduce computational complexity but also enhance model efficiency.

Perform PCA dimensionality reduction on the feature vector matrix \(\:X\):

Where \(\:{X}_{r}\) is the feature vector after dimensionality reduction, and \(\:W\) is the transformation matrix of PCA.

The dimensionality reduction operation projects the original 768-dimensional feature vector into a lower-dimensional space (e.g., 50 dimensions) to reduce redundant information and enhance the efficiency of subsequent matching calculations.

(3) Digital Characterization of Functional Features. First, use formula (10) to standardize the feature vector \(\:{X}_{r}\) after dimensionality reduction, normalizing the data to a range of 0–1 to obtain the standardized matrix \(\:{X}_{s}\).

Next, reshape the standardized feature vector \(\:{X}_{s}\) into a matrix \(\:M\in\:{R}^{m\times\:n}\) and visualize it using a heatmap.

Similarity matching of functional and technical features

To address the low efficiency of intelligent matching between product functional requirements and existing patent technical feature knowledge, which hinders the effective application of patent technologies in innovation, this paper proposes an intelligent patent technical feature matching method for product design functional requirements. The method achieves efficient and intelligent matching between functional requirements and patent technical features through feature vectorization, dimensionality reduction, and similarity calculation, providing technical knowledge support for design innovation. Using this method, designers can digitally represent functional requirements and related patent technical features, and apply image similarity algorithms to identify and match similar technical features, providing technical knowledge and inspiration for product design innovation. This method enables intelligent product innovation design and significantly improves the efficiency and approaches of design innovation.

The similarity matching method between functional requirements and patent technical features is as follows.

-

(1) The image after digital representation of the functional features in Sect. 2.4 is used as input, and feature vectors are extracted using the ResNet-50 (Residual Neural Network) model, followed by normalization37. ResNet-50 has advantages in image feature extraction, including deep feature extraction capabilities, the introduction of residual blocks to address the vanishing gradient problem, and the use of pre-trained models to save training time and enhance feature representation quality38. This model provides a solid foundation for subsequent similarity calculations when extracting functional requirements and patent technical features.

-

(2) The cosine angle between feature vectors is calculated using Formula (11) to measure the similarity between images. The cosine similarity value ranges from [−1, 1], with values closer to 1 indicating greater similarity between the two feature vectors, which intuitively reflects the degree of matching between functional requirements and patent technical features.

Where \(\:{V}_{r}^{{\prime\:}}\) is the standardized feature vector of the functional requirement;

\(\:{V}_{p}^{{\prime\:}}\)is the standardized feature vector of the patent technical feature.

Fuzzy comprehensive evaluation of solutions

The fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method is a multi-criteria decision-making approach based on fuzzy mathematics theory, widely applied to handle evaluation problems with uncertainty, fuzziness, and diversity. It is particularly suitable for scenarios such as design decisions and solution selection. The aim of this method is to provide a comprehensive evaluation of multiple solutions across different criteria to derive the final score for each solution, thereby assisting decision-makers in making optimal choices.

The process of fuzzy comprehensive evaluation involves the following steps:

First, the indicator weights \(\:{\text{w}}_{\text{i}}\) are calculated using formula (12).

Next, experts are invited to evaluate the satisfaction level of each solution, and the membership degree \(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{\text{i}\text{j}}\) of each solution under various evaluation criteria is obtained using formula (13), constructing the membership degree matrix.

Finally, the comprehensive membership degree \(\:{\text{b}}_{\text{j}}\) for each evaluation level is calculated using formula (14). The comprehensive evaluation score \(\:\text{S}\) of each solution is then calculated using formula (15).

Calculation of indicator weights:

Where \(\:{w}_{i}\) represents the weight of the \(\:i\)-th indicator;

\(h_j\) represents the importance of the technical feature for the \(\:i\)-th indicator;

\(\:\sum\:_{j=1}^{n}h_j\) is the total sum of the importance values of all technical features.

Calculation of membership degree:

Where \(\:{\mu\:}_{ij}\) is the membership degree of the \(\:i\)-th indicator at the \(\:j\)-th evaluation level;

\(\:{n}_{ij}\) is the number of evaluations for the \(\:i\)-th indicator at the \(\:j\)-th evaluation level;

\(\:\sum\:_{\text{k}=1}^{\text{m}}{\text{n}}_{\text{i}\text{k}}\) is the total number of evaluations for the \(\:\text{i}\)-th indicator.

Calculation of the comprehensive membership degree:

Where \(\:{\text{b}}_{\text{j}}\) is the comprehensive membership degree of the \(\:\text{j}\)-th evaluation level;

\(\:{\text{w}}_{\text{i}}\) is the weight of the \(\:\text{i}\)-th indicator;

\(\:{{\upmu\:}}_{\text{i}\text{j}}\) is the membership degree of the \(\:\text{i}\)-th indicator at the \(\:\text{j}\)-th evaluation level.

Calculation of the overall score for the scheme:

Where \(\:\text{S}\) is the overall score;

\(\:{\text{b}}_{\text{j}}\) is the comprehensive degree of membership for the \(\:\text{j}\)-th evaluation level;

\(\:{\text{v}}_{\text{j}}\) is the corresponding score for the \(\:\text{j}\)-th evaluation level.

Case study

This chapter uses an earthquake experience platform as a case for design innovation, providing a comprehensive introduction to the implementation process of the method, covering areas such as requirements analysis, functional mapping, functional requirement encoding, and patent technology feature extraction. The case overview is as follows.

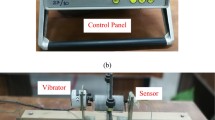

The earthquake experience platform is a simulation device designed to educate the public on how to take appropriate measures during an earthquake by simulating different earthquake scenarios. These platforms are typically equipped with vibration simulators and interactive scenes, allowing participants to experience an earthquake in a safe environment, thereby enhancing public awareness of earthquake disaster prevention and practicing emergency evacuation, hiding, and other survival techniques.

The earthquake experience platform consists of a high-precision vibration simulation system that uses electric or hydraulic mechanisms to generate vibrations of different intensities and frequencies, simulating real earthquake scenarios. Safety features, including safety belts, emergency stop buttons, and monitoring systems, ensure participants learn in a safe environment. The platform’s educational content is displayed through interactive devices, including earthquake knowledge, emergency sheltering techniques, and self-rescue and mutual aid methods. Additionally, the platform is equipped with a data collection system to analyze participants’ reactions and optimize educational programs. The operation interface allows for personalized adjustment of simulation parameters, enabling educators and learners to adjust the experience intensity according to different needs.

Requirement acquisition and classification for the earthquake experience platform

First, a needs survey was conducted through field research and interviews to comprehensively collect the original requirements for the earthquake experience platform, providing the foundation for subsequent needs classification and prioritization. The survey participants, aged between 18 and 45, included 92 individuals (8 of whom were earthquake experience equipment managers), all of whom had experience with earthquake simulation products and had an interest in earthquake experiences. The gender distribution was 53.3% male and 46.7% female. Subsequently, through focus group discussions, similar or related needs were summarized and integrated, ultimately forming the original requirements list, as shown in Table 1. From the collected requirements, it can be observed that, in addition to meeting the basic earthquake simulation functionality, the earthquake experience platform also involves safety, generalization, multi-sensory, and multi-scenario experiences.

Based on the original functional requirements of the earthquake experience platform in Table 1, a Kano questionnaire was developed, using a five-point Likert scale for measurement. The survey was conducted both online and offline, with the questionnaire design shown in Table 2.

The questionnaire included both positive and negative questions. Positive questions were designed to assess users’ satisfaction with specific features, such as “How would you feel if the collapse of objects could be simulated?” Negative questions aimed to evaluate users’ tolerance for the absence of specific features, such as “How would you feel if the collapse of objects could not be simulated?”

A total of 112 questionnaires were distributed. After excluding incomplete or contradictory responses, 100 valid questionnaires were collected, with a response rate of 89.3%. Among the respondents, 53 were male and 47 were female, aged between 18 and 45 years. The Better-Worse coefficient is calculated based on formulas (1) and (2), and a quadrant coordinate scatter plot is drawn. The survey and analysis results are shown in Table 3, and the Better-Worse quadrant coordinate distribution is shown in Fig. 2.

From the results, it can be seen that the functional requirements N1, N3, N8, and N12 for the earthquake experience platform are located in the fourth quadrant, which are Must-be requirements that must be met. N2, N4, and N16 are located in the first quadrant, which are One-dimensional requirements. These are competitive factors for the quality of the earthquake experience platform. If these functional requirements are met, making it superior and different from competitors, it will strengthen users’ good impression of this product. Therefore, these functional requirements need special attention. N5, N7, N11, and N15 are located in the second quadrant, which are Attractive requirements. These are surprise product functions that exceed user expectations and often bring higher loyalty. N6, N9, N10, N13, and N14 are located in the third quadrant, which are Indifferent requirements. These functional requirements can be ignored in the design.

G-HOQ correlation analysis of requirements and technical features

In order to map the requirement features into technical features and analyze the correlation between technical features and requirements as well as the engineering implementation importance, 15 design professionals were invited to analyze and evaluate the technical features of the essential, expected, and exciting requirements for the earthquake experience platform. These evaluators have extensive experience in product design, experience design, and user requirement analysis, with an average of 9 years in the industry. They are from 8 companies and 2 universities. The corresponding technical features were finally distilled, and the results are shown in Table 4.

Step 1. Importance scores for the requirement features Ni and technical features Yj are assigned based on four main criteria: the relevance between the requirement and technical features, implementation cost, technical feasibility, and potential impact on user experience. A 1–3–5–7−9 scoring scale is used to assess the relationship degree, with scores increasing from least important to most important, namely: “least important,” “not important,” “moderately important,” “important,” and “most important.” The requirement and technical feature evaluation table is then obtained, and the average score for each requirement feature is calculated.

Step 2. Set the earthquake experience platform user requirement features,,,,,,,,,, and N16 as reference sequences, and the technical features,,,,,,,,,, and Y16 as comparison sequences. Calculate the grey relational matrix between the requirements and technical features using formulas (3) and (4).

Step 3. The technical feature correlation matrix is filled into the HOQ, and the importance hj of the key technical features Yj for the earthquake experience platform is calculated and ranked according to Eq. (5). The positive and negative correlations between technical features are established. This completes the construction of the G-HOQ (Quality Function Deployment) house of quality, as shown in Fig. 3.

From Fig. 3, the ranking of technical feature importance is: Y1 Vibration, Y8 Sound Effects, Y16 Physiological Monitoring, Y7 Multi-Scenario Configuration, Y11 Wind and Rain Simulator, Y5 Virtual Reality, Y15 Portable and Mobile, Y12 Temperature Control, Y4 Multilingual Instruction, Y3 Accessibility, and Y2 Emergency Braking. Therefore, the design of the earthquake experience platform should focus on the following five main aspects:

(1) Multi-modal earthquake experience, where the equipment should be capable of switching between multiple scene modules and simulating corresponding sound effects and natural phenomena (e.g., wind, rain, temperature changes) based on the scene. (2) During the user experience, virtual reality should be integrated to provide an immersive experience. Additionally, the system should collect physiological data to assess the user’s condition in emergencies and provide recommended strategies. (3) The equipment should be portable for easy transport and installation, with accessible auxiliary facilities. (4) A comprehensive multi-language instructional unit for the device’s operation should be provided to meet the needs of users from different regions. (5) In case of an emergency or discomfort during the experience, the user should be able to activate the emergency brake.

Where Nk is the requirement feature, X0 is the requirement importance, and hj is the technical feature importance

Functional requirement coding and patent technical feature extraction

This section outlines the main steps of patent technical feature extraction, as shown in the flowchart in Fig. 4. First, patent search keywords and scope are defined based on functional requirements, followed by patent document retrieval to form the initial dataset. Next, the patent documents are read and preprocessed, including the removal of stopwords, tokenization, part-of-speech tagging, and dependency analysis. Finally, Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques are employed to extract N-V-N structures, and irrelevant features are filtered out using regular expressions, completing the extraction of patent technical features. The extracted valid features are then saved into a new document for subsequent visualization and analysis.

The specific implementation process for the functional requirement encoding and patent technical feature extraction of the earthquake experience platform is as follows:

Step 1: Encode the functional requirements of the earthquake experience platform using the N-V-N functional feature coding method described in Sect. 2.3.1. The results are shown in Table 5. During the coding conversion process, user requirements should be broken down into independent, singular functional requirements as much as possible to be consistent with the form of subsequent patent technical feature NLP extraction.

Step 2: Understand the functional features of the earthquake experience platform and construct patent search terms: earthquake, experience facilities. Then, search for relevant patents from the past five years on the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) platform, retrieving a total of 163 patent records, including 58 invention patents, 99 utility model patents, and 6 design patents. This study focuses on invention and utility model patents as the main technical documents, obtaining 157 patents. After screening out 7 patents with weak relevance, 150 patents were retained. Finally, extract the text of the claims and invention descriptions from the patent technical documents to serve as the corpus for the next step of NLP-based patent technical feature extraction.

Step 3: Extract patent technical features according to the method described in Sect. 2.3.2, forming a set of technical features \(\:F\). This task is implemented in a Python 3 environment within Jupyter Notebook, and the process includes data preprocessing, tokenization, part-of-speech tagging, dependency analysis, extraction of N-V-N structures, regular expression filtering, and saving and outputting the technical features. The specific process is as follows:

-

(1)

Use the HIT Chinese stop words list for data preprocessing.

-

(2)

Utilize the Chinese natural language processing model spaCy for word segmentation and part-of-speech tagging. Additionally, perform dependency analysis on the preprocessed text to extract technical features in the Noun-Verb-Noun (N-V-N) structure.

-

(3)

Use regular expressions to clean and filter out feature text (e.g., claim, described, including, comprises, a kind of, patent number) to make the extracted technical features more precise and concise. In this experiment, a total of 1766 technical features were extracted from 150 patents.

-

(4)

Store the extracted and filtered technical features in Word documents by patent name.

Digital characterization of functional and technical features

Digitize the extracted patent technical features and earthquake experience platform functional requirement features according to the method described in Sect. 2.4. The key processes include: text feature vectorization, dimensionality reduction and principal component extraction, and feature digital characterization.

Step 1: Text Feature Vectorization. Use the BERT pre-trained model to tokenize, label, and vectorize the earthquake experience platform functional requirements and patent technical features, ultimately representing each technical feature with a 768-dimensional vector.

Step 2: Dimensionality Reduction and Principal Component Extraction. Perform principal component analysis (PCA) using the PCA method to reduce the dimensionality of the feature vectors according to formula (9). Simultaneously, plot the cumulative explained variance graph to identify the number of principal components that can explain over 95% of the variance, as shown in Fig. 5. The analysis results indicate that with 292 dimensions, the cumulative explained variance is 95%. To standardize the shape of the images during digital characterization, 300 dimensions were selected as the digital characterization dimension.

Step 3: Digital Characterization of Features. Normalize the dimensionally reduced vectors according to formula (10). Use the heatmap function in the Seaborn tool to reshape the dimensionally reduced vectors into a 10 × 30 shape and generate a heatmap, completing the digital characterization of the earthquake experience platform’s functional requirements and patent technical features. The digital characterization process of functional requirements is shown in Fig. 6, and the digital characterization process of patent technical features is shown in Fig. 7.

Feature matching and filtering

First, extract features from the digital images of the earthquake experience platform’s functional requirements and patent technical features using the method described in Sect. 2.5. Calculate the cosine similarity between the features using formula (11), and the results are shown in Table 6.

Next, select the functional requirements and patent technical features with the highest similarity values as the best matching results, as shown in Table 7.

Construction of the functional model for the earthquake experience platform

Based on the matching results in Sect. 3.5 and the understanding of the original product requirements, construct the functional model of the earthquake experience platform, as shown in Fig. 8. The process and explanation of the functional model construction are as follows.

First, according to the classification results of functional requirements in Sect. 3.1 and 3.3, R1-R2, R6-R7, R16, and R19 are Must-be requirements, which are essential functions. Based on the best matching results in Table 6, select an earthquake simulation experience system and method using VR technology (CN202311629779.9)39 and a six-degree-of-freedom platform for earthquake simulation experience equipment (CN202221992770.5)40 to achieve R1 simulating the intensity of earthquakes and R2 different types of earthquakes. Choose a tilted component from an earthquake escape simulation drill device (CN202122920277.4)41 as the basic structure for R6 and R7 auxiliary facility wheelchair access. Select the virtual earthquake disaster scenario optimization method from a virtual earthquake rescue drill system patent (CN202111246012.9)42 combined with a temperature control device to achieve R19’s function of simulating temperature changes based on the scenario.

Secondly, construct functional prototypes for the One-dimensional requirements R3-R5, R8-R9, and R22-R25. R3, R4, and R5 belong to the equipment safety protection devices, including emergency stop functions and safety protection facilities. Based on the matching results, select the protective devices proposed in the patents for an experiential comprehensive safety training facility (CN202021278885.9)43 and a VR real earthquake experience device for earthquake museums (CN202120986637.8)44 as the foundation. Choose the interface form from a neural network and virtual reality-based multi-scenario earthquake escape drill system for campuses (CN202311396237.1)45 as the prototype for R8 and R9 multilingual selection and output. R22-R25 involve monitoring the physiological indicators of participants. Since the earthquake experience platform focuses on the experiential aspect, precise monitoring of participants’ physiological indicators is unnecessary and can be done through the use of smart wristbands.

Finally, construct functional prototypes for the Attractive requirements R10-R15, R17-R18, and R20-R21. R10-R15 involve the simulation of virtual earthquake scenarios, which can be achieved by using the methods described in a virtual simulation-based earthquake scenario simulation and risk avoidance training device (CN202321665823.7)46 and an earthquake simulation experience system and method using VR technology (CN202311629779.9)38 for scene modeling and simulation. R17-R18, the simulation of wind and rain environments, can be achieved by configuring water tanks, fans, and atomizers. R20-R21 can be realized through modularization and built-in mobile wheels for easy assembly, disassembly, and mobility of the equipment.

Design and evaluation

Design plan and explanation

To verify the effectiveness of the method, the design scheme was divided into two groups, A and B, which completed the design independently. Group A consisted of one designer who used the methods and processes described in the paper. Group B served as the control group, composed of three designers who employed traditional design processes and methods. The design process for groups A and B was documented, including the time taken, sources of information, and product feature settings, for comparative analysis.

The design scheme of Group A is based on the matched patent technical features from Sect. 3.5 and the summarized functional architecture of the earthquake experience platform in Sect. 3.6. The design scheme is shown in Fig. 9, with the key design points explained as follows:

-

(1)

To provide a more realistic experience and accommodate a wider range of people, the earthquake experience platform uses a standing experience mode. A six-degree-of-freedom platform is used to simulate different types and intensities of earthquakes.

-

(2)

The earthquake experience platform is equipped with temperature control and fan atomization devices. The top and sides of the equipment have air vents to simulate changes in environmental temperature and weather under different scenarios, providing a multi-modal earthquake experience.

-

(3)

Foam drop simulation blocks are set at the top of the equipment to simulate debris falling during an earthquake.

-

(4)

A prominent emergency stop button is located on the left side of the equipment, and semi-enclosed protective panels and guardrails surround it to provide comprehensive safety protection for participants. Lights are set around the top and bottom to simulate environmental changes and create ambiance.

-

(5)

The equipment is equipped with VR glasses, scene simulation screens, and speakers to provide a multi-scenario, immersive earthquake experience. The control interactive screen is used for equipment control, language selection, and instructions.

-

(6)

The equipment is equipped with wristbands to monitor the physiological indicators of participants, providing assessments and suggestions for psychological responses.

-

(7)

The equipment can be accessed via steps or an accessible ramp, accommodating the needs of special groups.

-

(8)

An adjustable mobile base is set at the bottom of the equipment, making it easy to level and move the equipment.

Group B includes three designs. Designers developed these based on their own experience and understanding of the product. The designs are shown in Fig. 10. Design a uses a three-degree-of-freedom platform, a standing experience mode, and a step-in entry. It is equipped with VR glasses, and semi-enclosed side panels provide safety protection for participants. Design b uses a six-degree-of-freedom platform, a sitting experience mode, and is equipped with VR glasses. The low platform design facilitates easy entry and exit for participants. Design c uses a low-position vibration platform, making it easy for participants to enter. It provides a standing experience mode and is equipped with an LCD screen for playing and switching earthquake scenarios.

Scheme comparison and analysis

By recording and comparing the differences between Group A and Group B design schemes in terms of time taken, functional features, and sources of design reference materials (as shown in Table 8), we found that Group A completed their design in the shortest time of 18.4 h, while Group B took an average of 24.1 h, significantly longer than Group A. The time statistics here cover the period from requirement analysis to the completion of the design scheme, but do not include the earlier stages of basic research (case collection, literature review). Meanwhile, in the three critical stages of patent NLP feature extraction, digital representation of functional features, and image similarity matching, Group A’s solution utilized the pre-set model code described in this paper, requiring no complex training or re-modeling. In the comparison of functional features for the earthquake experience platform, Group A’s solution exhibited richer features, more closely aligning with user needs, and achieved a 23.65% improvement in design efficiency.

In contrast, Group B’s schemes were limited by the designers’ personal understanding and existing product cases, resulting in more basic functional designs that lacked One-dimensional and Attractive features.In terms of sources of design reference materials, Group A not only referred to existing cases but also covered 150 related patent documents, while Group B mainly relied on case references. The reason for this difference lies in the difficulty of reading and understanding patent documents, and in traditional design practice, the method of using patent documents to obtain innovative technology is not yet mature. Most designers have not developed the habit of using patents in the early stages of design to seek technical innovation. Typically, in traditional design processes, designers encounter patent documents mainly after the technical scheme is completed, to draft patent application documents, rather than utilizing patents for innovation at the beginning of the design process.

Scheme evaluation

The fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method47 is used to assess the requirement satisfaction for the four solutions from Groups A and B. The evaluation criteria are based on the 11 requirement features of the earthquake experience platform proposed in Sect. 3.2. The weight of each criterion is derived from the importance of the technical features, and the weights are normalized by summing and applying Formula (12). The evaluation criteria consist of four categories (Very Satisfied, Satisfied, Neutral, and Dissatisfied), with corresponding scores of 4, 3, 2, and 1, respectively. A total of 63 participants were invited for the evaluation, including 26 designers (9 frontline designers and 17 university faculty members and students with backgrounds in industrial design and mechanical design) and 46 users. The evaluation criteria system and the evaluation results are presented in Table 9.

The overall membership degree is calculated using the fuzzy weighted average method (via formulas 13–14), and the comprehensive score of each scheme is obtained using formula (15) and ranked accordingly. The results of the comprehensive evaluation are shown in Table 10. According to the maximum membership degree rule, the overall evaluation of Scheme A is “Very Satisfied” with a membership degree of 0.457 and a comprehensive score of 3.287. The overall evaluation of the three schemes in Group B is “Average.” The evaluation results clearly show that the demand satisfaction for Scheme A is significantly higher than that of Group B, thus validating the effectiveness and practicality of the design innovation method proposed in this study.

Discussion

Research value

This research proposes a systematic product design method from requirement analysis to design innovation, aiming to achieve effective mapping between requirements, functions, and technical knowledge. Based on the Kano model combined with grey relational analysis and the House of Quality, the study introduces the G-HOQ model for requirement mining, classification, and functional mapping. This method can accurately mine user requirements in small sample conditions and reduce subjectivity in decision-making.

Furthermore, to enhance the efficiency and methods for designers in seeking functional and technical knowledge during the innovation process, this paper proposes a method based on NLP, digital characterization technology, and image similarity algorithms to identify and match technical features from patent literature according to requirements. Utilizing the rich resources of patent knowledge for design innovation activities not only broadens the sources of innovative knowledge for designers and enriches their design inspiration but also allows for the recombination and utilization of the latest technical knowledge in related fields.

Traditional product design methods mostly focus on only part of the design process. In contrast, a systematic product design approach ensures that design knowledge is coherent, well-founded, and traceable, reducing randomness, uncertainty, and fragmentation of knowledge in the design process. This makes the product design process more efficient and purposeful, enhancing design efficiency and innovation levels, thus filling a gap in this field.

Limitations of the study

Some limitations of this study and directions for future work are as follows.

-

(1)

The patent technical features extracted from the N-V-N structure using the method have certain accuracy limitations, and some results fail to accurately and completely describe the relationships and action properties between components. The accuracy of technical feature extraction is a key factor affecting the quality of subsequent matching and the effectiveness of design innovation. In the experiment, we used the N-V-N structure for patent technical feature extraction, but some of the extracted technical features from certain patent documents, such as those from the patent “Transverse and Longitudinal Seismic Experience Platform” (CN202220214452.X), include N-V-N features like: feature2 = “when switching to seismic isolation” and feature6 = “directional transverse wave electric cylinder”. From these outputs, it is clear that they fail to fully describe the relationships and action properties between components. There are three main reasons for this issue: first, the complexity of Chinese patent corpora, where long sentences, ambiguity, and industry-specific terms may cause key information to be lost during the word segmentation and sentence splitting stages. Second, the limitations of the text preprocessing strategy, which may be influenced by the rules of word segmentation, sentence splitting, and regular expression filtering during text preprocessing, leading to the omission of certain key verbs or nouns. Third, the insufficient contextual understanding of semantic models. Currently, the N-V-N extraction method only focuses on sentence-level semantics and fails to fully capture the implicit logic within technical features. Additionally, the complexity of the Chinese patent corpus structure and the aim for simplified expression of the patent technical feature recognition results in the experiment are also direct contributing factors.

To assess the accuracy of technical feature extraction, we extracted 1,766 technical features from 150 patents, of which 1,525 were valid features, 241 were inaccurate, resulting in a usability rate of 86.35%. This indicates that, although the extraction of technical features is not completely accurate, it still holds significant academic and practical value overall.

Therefore, future research should expand the contextual relationships within the N-V-N structure and develop patent technical feature mining techniques that are more aligned with cognitive understanding, in order to improve the accuracy and reliability of feature extraction.

-

(2)

Experimental results indicate that the proposed method achieves the matching of requirement features with patent technical features, significantly improving the efficiency of designers in reviewing and understanding patent technical documents, and gaining insights into the technical status and innovations in relevant fields. Additionally, it stimulates design innovation through external design knowledge. However, the matching results should not be directly used as the sole standard for technical innovation. Currently, the method requires designers’ experience for technical selection, evaluation, and reorganization based on the identified matching results. Future research will incorporate AI tools to provide design scheme suggestions based on matching results, enhancing design efficiency and innovation.

-

(3)

The functional requirement coding process involves subjective elements influenced by the coder’s design experience and understanding of the coding implications. Different coders may have varying interpretations of the same task, affecting subsequent technical feature matching results. However, considering design diversity and the non-uniqueness of innovation, this difference preserves the diversity of design schemes, enriching the technological routes for design innovation.

-

(4)

The patent technical feature recognition method proposed in this paper is primarily aimed at Chinese patent literature and has not yet been validated for its applicability to international patent literature. Due to differences in language, structure, and expression conventions between domestic and international patent literature, the effectiveness of this method in international patent documents has not been evaluated. Therefore, the generalizability of the method still needs further validation. In future research, we will conduct an in-depth exploration of this limitation and assess the applicability of this method in international patent literature, specifically focusing on aspects such as the accuracy and usability of technical feature extraction. Although the method has not been validated in international patent literature, it still possesses potential cross-lingual applicability from a theoretical perspective for the following reasons:

Firstly, the BERT model used in this paper has a multilingual version that supports semantic representation in multiple languages, making it applicable to international patent literature. Secondly, the N-V-N structure is highly universal as a functional description framework, with its core logic (noun-verb-noun relationships) independent of any specific language, thereby offering strong cross-lingual applicability. Thirdly, the universality of text preprocessing, such as tokenization, stopword filtering, and normalization rules, can be adapted for different languages (e.g., English tokenization tools and stopword lists can be used for English), making the method adaptable to patent literature in different languages.

Therefore, although the effectiveness of the method has not yet been validated in international patent literature, its core logic demonstrates good scalability and lays a foundation for future research on adapting the method to international patent literature.

Conclusion

This study proposes a method that combines Kano, GRA, QFD, PCA, and NLP for the digital characterization and intelligent identification and matching of functional requirements and patent technical features. This method achieves effective mapping between requirements, functions, and technical knowledge, providing a practical and systematic approach for product design innovation.

Firstly, this study integrates GRA to improve the QFD method and proposes the G-HOQ functional mapping and technical feature correlation analysis method. This approach avoids subjective interference in small sample scenarios and provides weights and indicators for design evaluation. Secondly, the study constructs an N-V-N technical feature extraction structure and applies NLP, the BERT model, PCA, and cosine similarity algorithms to propose a design innovation method for intelligent extraction, visualization, and matching of patent technical features. This method enables the rapid and effective identification of technical features that meet product functional requirements from patent documents, thereby enhancing design innovation efficiency and the intelligent design level of product technical solutions. Finally, the feasibility and effectiveness of the method were comprehensively validated through the design and evaluation of the earthquake experience platform. The results indicate that this method significantly reduces the difficulty for designers in reviewing and understanding patent technical documents, expands the sources of design knowledge, and provides ample inspiration for design innovation. Additionally, the proposed method can offer designers intelligent means for technical innovation and access to technical resources, thus facilitating efficient, scientific, and high-quality design innovation activities.

Data availability

Data availability statement Data associated with the study has not been deposited into a publicly available repository and data will be made available on request. For research inquiries, please contact the author Jianwei Yang at 1230211018@stu.xaut.edu.cn.

Change history

23 July 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the Acknowledgements section. It now reads: “We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the editor, Dr. Balaji Devarajan, and the three anonymous reviewers for their meticulous review and valuable suggestions on this research. We also thank all the participants in this experiment for their active involvement and valuable time, which provided essential experimental data for this study. Your contributions are greatly appreciated in advancing scientific research. Our thanks also go to all the scholars whose theoretical foundations have supported this study. Their research outcomes have provided important references and insights for the development and implementation of this paper. Furthermore, this paper was supported by the Shaanxi Provincial Art Science Planning Project in 2023 (Project No. 2023HZ1777), the Shaanxi Provincial Art Science Planning Project in 2023 (Project No. 2023HZ1758), and the Shaanxi Provincial Science and Technology Plan Project in 2024 (Project No. 2024GX-YBXM-529).”

References

Kang, B. et al. Prototyping to elicit user requirements for product development: using head-mounted augmented reality when designing interactive devices. Des. Stud. 84, 101147 (2023).

Xu, X. Q. et al. Quality improvement method for high-end equipment’s functional requirements based on user stories. Adv. Eng. Inf. 56, 102017 (2023).

Xie, X. Y. The cognitive process of creative design: A perspective of divergent thinking. Think. Skills Creat. 48, 101266 (2023).

Li, M. D. et al. A cognitive analysis-based key concepts derivation approach for product design. Expert Syst. Appl. 236, 121289 (2024).

Ebrahimi, B., Bataleblu, A. A. & Roshanian, J. Developing an intelligent systems design framework based on multidisciplinary design analysis and multi-agent thinking integration. Expert Syst. Appl. 248, 123363 (2024).

Fu, X. Y. et al. A constraint-driven conceptual design approach for product based on function-behavior-structure design process. Comput. Ind. Eng. 189, 109994 (2024).

Lou, S. H. et al. A function-behavior mapping approach for product conceptual design inspired by memory mechanism. Adv. Eng. Inf. 58, 102236 (2023).

Hao, J. et al. Module division method of complex products for responding to user’s requirements. Alex Eng. J. 82, 404–413 (2023).

Sun, H. et al. An analysis method of dynamic requirement change in product design. Comput. Ind. Eng. 171, 108477 (2022).

Lee, C. H. et al. Requirement-driven evolution and strategy-enabled service design for new customized quick-response product order fulfillment process. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 176, 121464 (2022).

Yazdani, M. et al. A fuzzy multi attribute decision framework with integration of QFD and grey relational analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 115, 474–485 (2019).

Fargnoli, M. & Haber, N. A practical ANP-QFD methodology for dealing with requirements’ inner dependency in PSS development. Comput. Ind. Eng. 127, 536–548 (2019).

Wu, X. L. et al. A function combined baby stroller design method developed by fusing Kano, QFD and FAST methodologies. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 75, 102867 (2020).

Wu, C. J. et al. Innovative design of bamboo chair furniture based on KANO model and TRIZ theory. J. Eng. 9, 177–183 (2024).

Yang, B., Liu, Y. & Chen, W. A twin data-driven approach for user-experience based design innovation. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 68, 102595 (2023).

Lu, W. et al. User review Data-Driven product optimization design method. J. Comput. -Aided Des. Comput. Graph. 34, 482–490 (2022).

Wu, J. M. et al. Intelligent design method of mine tunnel portal driven by knowledge graph. Comput. Geotech. 173, 106431 (2024).

Deng, J. X. et al. Intelligent optimization design of squeeze casting process parameters based on neural network and improved sparrow search algorithm. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 39, 100600 (2024).

Geum, Y. & Kim, M. How to identify promising chances for technological innovation: Keygraph-based patent analysis. Adv. Eng. Inf. 46, 101155 (2020).

Noh, H., Jo, Y. & Lee, S. Keyword selection and processing strategy for applying text mining to patent analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 42, 4348–4360 (2015).

Zhang, P. et al. Research on digital characterization and identification process model of functional genes for intelligent innovative design. Adv. Eng. Inf. 56, 101983 (2023).

Yun, S., Cho, W., Kim, C. & Lee, S. Technological trend mining: identifying new technology opportunities using patent semantic analysis. Inf. Process. Manage. 59, 102993 (2022).

Han, X. D., Zhu, D. H., Lei, M. & Daim, T. R&D trend analysis based on patent mining: an integrated use of patent applications and invalidation data. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 167, 120691 (2021).

Yuan, Y. X. & Yuan, X. D. The advances and opportunities of developing solid-state battery technology: based on the patent information relation matrix. Energy 296, 131178 (2024).

Wang, T. et al. A novel user-generated content-driven and Kano model focused framework to explore the impact mechanism of continuance intention to use mobile apps. Comput. Hum. Behav. 157, 108252 (2024).

Karasan, A., Ilbahar, E., Cebi, S. & Kahraman, C. Customer-oriented product design using an integrated neutrosophic AHP & DEMATEL & QFD methodology. Appl. Soft Comput. 118, 108445 (2022).

Liu, P. D., Fu, Y. X., Wang, P. & Wu, X. Grey relational analysis- and clustering-based opinion dynamics model in social network group decision making. Inf. Sci. 647, 119545 (2023).

Long, Y. C., Zhao, W. & Chen, L. A multi-objective tool selection method using FAHP and cosine similarity. Procedia CIRP. 104, 1843–1848 (2021).

Tian, Y. et al. An individual-based spatio-temporal travel demand mining method and its application in improving rebalancing for free-floating bike-sharing system. Adv. Eng. Inf. 50, 101365 (2021).

Babaei, M. et al. A data-mining based optimal demand response program for smart home with energy storages and electric vehicles. J. Energy Storage. 36, 102407 (2021).

Chen, J. et al. Integrated method of concept design of intelligent cockpit flexible testbench based on user requirement orientation. J. Mach. Des. 41, 170–176 (2024).

Xiong, T. T., Lin, Y. X. & An, X. Q. Crawler mobile crusher based on AHP-QFD theory. J. Mach. Des. 40, 27–32 (2023).

Chen, L., Chen, L. L. & Xu, H. Y. A global literature review in recent advancement of patent mining. Libr. Inf. Serv. 40, 84–89 (2020).

Yu, F. et al. Yang, an approach for radical innovative design based on cross-domain technology mining in patents. Int. J. Prod. Res. (2022).

Sun, Y. D. et al. Effective design knowledge abstraction from Chinese patents based on a meta-model of the patent design knowledge graph. Comput. Ind. 142, 103749 (2022).

Nasreen, G. et al. Email spam detection by deep learning models using novel feature selection technique and BERT. Egypt. Inf. J. 26, 100473 (2024).

Xu, J. W. et al. A fish behavior recognition model based on multi-level fusion of sound and vision U-fusionNet-ResNet50 + SENet. J. Dalian Ocean. Univ. 38, 348–356 (2023).

Liu, Y. B. et al. Apple phenological period identification in natural environment based on improved ResNet50 model. Smart Agric. 5, 13–22 (2023).

Ga, Y. Q. A VR technology-based earthquake simulation experience system and method. China patent CN202311629779.9 (2024).

Bian, F. A six-degree-of-freedom platform-based simulated earthquake experience device. China patent CN202221992770.5 (2022).