Abstract

This study investigates the use of magnesium phosphate cement (MPC), synthesised using waste refractory magnesia bricks (WRMB) and potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KDP), as a surface modifier to enhance recycled concrete aggregate (RA) performance. In India and China, WRMB recycling rates remain low at only 20%. The treatment involved blending of synthesised MPC powder and slurry with RA at a ratio of 1:8 by weight under both saturated and non-saturated conditions. The RA treated with slurry-saturated blend (MRA-IV) increased specific gravity by 17% and reduced water absorption, aggregate crushing value, and impact value by 34%, 14%, and 16%, respectively. MRA exhibited a 37% reduction in porosity and surface cracks. A concrete mix for M40 with 50% replacement of natural aggregate (NA) by RA and MRA was prepared. MRA-IV in concrete compressive strength improved by 58%, abrasion resistance by 19%, and tensile strength by 26%. A 50% replacement of NA significantly contributes to natural resource conservation while enabling waste reuse without compromising desirable properties. RA is a major component of construction and demolition (C&D) waste, but its high porosity and surface cracks limit its application. This study demonstrates the potential of MPC treatment in enhancing RA for sustainable concrete applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

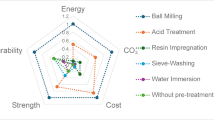

Recently, there has been a growing emphasis on the treatment of construction and demolition (C&D) waste due to its significant environmental impact1,2. Poor management and underutilization of C&D waste result in landfilling and resource wastage3,4. An estimated 27 billion tons of C&D waste are projected to be generated globally by 2050, making its scientific management a pressing concern5. Current sustainable strategies often struggle to encourage the reuse of C&D waste6,7. This is because C&D waste is often considered inferior to virgin building materials and classified as lower potential building material8,9,10. This classification limits the recycling potential and creates challenges for sustainable construction practices. C&D waste comprises of recycled concrete, with aggregates constituting 55–65% of the total waste11. These are referred to as recycled concrete aggregates (RA), and are further classified by size into coarse and fine recycled aggregates. RA has a residual parent mortar layer, known as adhered mortar, which leads to excessive water absorption, higher impact and crushing values, and a lower specific gravity. It hampers the performance of RA12,13, rendering it unsuitable for use in standard grade concrete applications14. The global substitution limit of RA viz. 20–35%15 is primarily due to its high-water absorption, lower density, and weaker ITZ, which affect concrete durability and strength16,17. Concrete is a three-phase material composed of cement paste, aggregate, and the interfacial transition zone (ITZ)18. Previous research has demonstrated that the ITZ has a primary influence on the characteristics of concrete19. The use of RA in new concrete poses challenges in achieving the targeted strength and quality of concrete owing to the presence of an older ITZ. Several treatment methods have been explored to improve the physical, mechanical and microstructural properties of RA, which can be classified as ; (1) techniques for removing adhered mortar from RA, such as ball milling20, microwave heating21, ultrasonic cleaning , chemical treatments , mechanical rubbing, and pre-soaking in water followed by rubbing; and (2) methods for improving the adhered mortar, including nano-silica treatments22, bio-cementitious material intrusion23, and cementitious coatings24. Table 1 gives the comparison between the existing methods of the RA treatment.

Conventional treatments, such as polymer-based modification, primarily reduce water absorption and enhance the ITZ but have limited impact on strength and durability under extreme conditions31. As shown in Table 1, various methods including washing, mechanical abrasion, thermal and chemical treatments have been studied to improve RA properties. However, these methods are energy intensive, requires additional setup, and degrade aggregates. Moreover, conventional methods fail to significantly enhance the durability and strength of RA, which limit the use to higher-grade concrete applications. Given the limitations of conventional RA treatment methods, alternative approaches such as coating with cementations material has gained attentions. Magnesia bricks are used in the refractory, furnace, and metallurgical industries as heat resistor. However, the waste refractory magnesia bricks (WRMB) generated during industrial production is often disposed of in landfills or recycled into low-value products like masonry bricks. In China and India, the annual recovery rate is below 25%32. The magnesia content in WRMB ranges from 60 to 80%, but only the reactive magnesium oxide (MgO) contributes to magnesium phosphate cement (MPC) formation, as confirmed by XRD analysis showing struvite-K formation33. MPC can be synthesised by blending finely crushed WRMB with potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KDP), where the reactive MgO in WRMB reacts with KDP to form struvite-k34. Studies indicate that MPC achieves 60–70% of its ultimate strength within 24 h35. Hydrated products of MPC penetrate the mortar surface and act as connections between the existing and new mortar 33,36,37. While using cementitious material as a doping/coating material for RA, mix design and mixing procedure play a crucial role. Tam et al.38 introduced two-stage mixing approach for producing recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) and concluded improvement in the compressive strength, reduced water permeability, and improved chloride ion resistance of the concrete39,40.

Methodology

In the present study C&D waste was collected from the recycling unit. RA of size 10 and 20 mm is used41. A detailed laboratory analysis was conducted to assess its physical and mechanical properties including sieve analysis, water absorption, specific gravity, aggregate impact value and aggregate crushing value. Additionally microstructural analysis such as X-ray diffraction (XRD), Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry (MIP) were performed. In the laboratory MPC was synthesised using WRMB and KDP as an activator. In the preliminary trial MPC and RA were mixed in weight ratios of 1:6, 1:8 and 1:10. Visual observation confirmed a non-uniform coating of RA at a 1:10 ratio, thus the ratio 1:8 was selected for further processing. Although 1:6 also provided uniform coating it is uneconomical as compared to 1:8. Modified RA (MRA) was prepared in four different ways; MRA-I (non saturated powder blending soaking 5 min), MRA-II (non saturated slurry blending, soaking 30 min), MRA-III (saturated powder blending soaking 5 min), and MRA-IV (saturated slurry blending, soaking 30 min), Since MPC is a fast-setting binder, the water-to-dry MPC ratio in slurry blending was set at 0.5. Consequently, the prepared slurry required additional setting time, leading to a soaking duration of 30 min. In contrast, for powder blending, the water-to-dry MPC ratio was 0.16, which did not require additional setting time, making its blending period only 5 min. MRA were then immersed for three days to ensure uniform hydration and stabilization of the surface modifications, as insufficient hydration may prolong the setting time. These MRA was used in M-40 grade concrete mixture using a two-step mixing procedure. The mechanical performance of the resulting concrete was evaluated in terms of compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, abrasion resistance, and flexural strength. Figure 1 depicts the methodology used to modify RA with MPC.

Experimental program

Materials

MPC

MPC was synthesised in laboratory in sufficient quantity, detailed methodology for the MPC synthesis is displayed in Fig. 2. For this WRMB powder were mixed with and without calcination with KDP in a weight ratio of 1:3, 1:4 and 1:542. Table 2 lists the chemical compositions of raw material used in the synthesis. Setting time and compressive strength of synthesised MPC was tested and found to be 29 min and 45 MPa. This mixture is classified as a rapid-curing cementitious material43,44.

Constituents of concrete

Portland cement conforming to ASTM C15045, was used in this study; the properties are given in Table 3. Natural coarse aggregate (NA) and river sand (RS) were procured locally and tested according to ASTM C136, C127 and ASTM C12846,47,48. C&D waste was collected from a recycling plant situated in study region. Table 4 shows the properties of the aggregates used.

Sample preparation

To investigate the effect of MPC treatment on RA and its further impact on RAC. Concrete samples were casted with a 50% replacement of NA to test the compressive strength, flexural tensile strength, splitting tensile strength, and abrasion resistance. As shown in Fig. 3, a two-stage mix design approach was adopted. The target compressive strength was M40, since globally it is most adopted grade of concrete. The mix proportions are given in Table 5.

Result and discussion

Analysis of synthesised MPC

The desirable properties of MPC as a treatment material include quick setting and early strength gain. The MPC was analysed for these properties. Figure 4 shows an SEM image of the WRMB, where surface texture is rough and irregular, at normal temperature. Figures 5 and 6 illustrate the variations in consistency, final setting time, and compressive strength at 1, 3, 7 and 28 days after mixing as a function of the calcination temperature where the calcination temperature was in the range of 100–300 °C, which is represented by the blue circles. Since it is observed that the mixture gives best results without calcination, as approximately 60–70% of the ultimate compressive strength is attained within 72 h of normal water curing, where the pH of curing water was in the range of 5.5–7.5. As the WRMB/KDP ratio increases, the setting time consistently increases. This occurs because, with an insufficient WRMB/KDP ratio, the gel formed during the hydration reaction coats the MgO particles, leading to a lower relative concentration of MgO and consequently prolonging the setting time49, In the context MPC the gel formed during the hydration reaction is primarily composed of magnesium phosphate hydrates, specifically struvite (MgNH4PO4·6H2O) and other related phases, as shown in Fig. 14. The WRMB/KDP ratio is a critical factor that influences the compressive strength of MPC; During the experimentation, the water to mix ratio were varied from 0.13, 0.16 and 0.19, but 0.16 gives maximum strength, as 0.13 is observed as insufficient ration and 0.19 is beyond optimum limit49. A higher WRMB/KDP ratio typically enhances the compressive strength owing to the increased Mg content, which promotes better hydration reactions and strengthens the cement matrix50,51,52. However, in the present experimental analysis, 1:4 was identified as the best combination with desired properties.

Variation of compressive strength of MPC ASTM C10953.

Physical properties of aggregates

Literature suggests that the physical and mechanical properties of recycled aggregate (RA) vary, with water absorption ranging from 3.16 to 7% and specific gravity ranging from 2.21 to 2.6554. The treatment to be effective the treated aggregates must exhibit an improvement in these properties. The effect of the MPC treatment on the RA was analysed by comparing the physical, mechanical, and microstructural properties before and after the treatment, such as water absorption, specific gravity, aggregate crushing value, aggregate impact value, SEM, and MIP of the NA with respect to the RA and MRA. Water absorption, a measure of porosity, decreased by 34%, because the pores and surface cracks are filled with MPC binder layer. The specific gravity, which indicates the relative weight, increased by 17.45%, indicating improved aggregate performance. The 16% decrease in the ACV and 14% decrease in the AIV indicated enhancements in strength, toughness, and impact resistance. Figures 7, 8, 9 and 10 show the RA, SEM image of RA, MRA-IV, and SEM of MRA-IV, respectively. An initial trial was conducted at a 1:10 proportion, and the physical and mechanical properties of the aggregates were evaluated. The results showed only minor performance enhancements for RA. Specific gravity increased by 7%, whereas reductions of 12%, 4%, and 9% were observed in water absorption, aggregate crushing value, and aggregate impact value, respectively.

As shown in Fig. 8, the untreated RA has plenty of voids and surface cracks a major drawback for quality reduction, but Fig. 10 displays the deposition of MPC voids and surface cracks are marginally reduced. To prove the deposition of MPC EDS analysis were conducted. Figures 11 and 12 illustrate the EDS analysis of RA and MRA-IV, revealing significant differences in the elemental compositions of RA and MRA-IV. RA displayed higher levels of calcium (Ca) and silicon (Si), indicative of adhered mortar on the aggregate surface. After treatment, the EDS spectra demonstrated the presence of magnesium (Mg) and phosphorus (P), confirming the deposition of MPC on the aggregate. Additionally, a notable reduction in the silicon content was observed, suggesting a deposition of newer surface layer. These compositional changes were consistent with the improved mechanical properties of the treated RA.

MIP was conducted to evaluate the pore structure modifications in aggregate samples pre and post treatment. The cumulative pore volume as a function of pore diameter is presented in Fig. 13. The results indicate a significant reduction in cumulative pore volume for all treated aggregates, with MRA-IV exhibiting the lowest pore volume. The untreated RA exhibited a higher cumulative pore volume, suggesting the presence of a more porous and heterogeneous structure, which negatively impact the mechanical and durability properties of concrete. Treated aggregates showed a progressive decrease in macropores (> 1000 nm) and an increase in mesopores (2–50 nm), leading to a more compact and refined pore structure. The reduction in interconnected pores is particularly beneficial as it minimises water absorption. Among the treated samples, MRA-IV demonstrated a 37% reduction in total porosity, confirming the effectiveness of the applied surface modification technique.

Figure 14 shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of MRA-IV. The analysis revealed the presence of key minerals: quartz, indicated by peaks at 26.5°, 50.0°, 59.9°, and 67.6°; sepiolite at 27.4° and 27.8°; and magnesia and struvite (MgNH4PO4·6H2O) at 29.3°, 36.5°, and 21.0°, respectively. The main components of the MPC coatings were struvite, sepiolite, and magnesia. These hydration products effectively filled the pores and cracks in RA, enhancing its structural integrity. Struvite acts as a gel that significantly contributes to the bond between MPC coating to the RA. In the context of MPC, the gel formed during the hydration reaction is primarily composed of magnesium phosphate hydrates, specifically struvite (MgNH4PO4·6H2O) and other related phases, as shown in Fig. 14. The prolonged initiated final setting times observed with MRA as a replacement for NA can be attributed to water competition between the MPC hydration products (struvite, M–S–H, etc.) and the hydration of Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC). The MPC coating consumes some of the available water for its own hydration, and the higher water absorption of RA exacerbates this effect. Additionally, the chemical reactions involved in struvite and magnesium silicate hydrate (MSH) formation further consume water. Making it unavailable for proper hydration. This result in delay in the setting time.

This suggests that the treatment effectively reduced the porosity. The results highlight the influence of the treatment on pore structure modification. Figures 15, 16, 17 and 18 show the improvement in the aggregate properties.

Mechanical properties of RAC

Compressive strength

MRA when used in concrete exhibit improvement in properties compared to untreated RA. The impact of MPC treatment on the compressive strength development of concrete at 7th and 28th days are shown in Fig. 19; the test was conducted in accordance with ASTM C3955. When 50% of the NA was replaced with RA, the compressive strength of the concrete was 30% lower compared to control mix. In contrast, the compressive strength of MRA-IV experienced a significant increase of 59%, clearly demonstrating that surface modifications positively impact the strength of RA. Figure 20 shows the adhered layer between the MRA and new Portland cement mortar. The image reveals a yellow coating, which corresponds to the hardened MPC paste. This coating plays a key role in strength compared to the untreated RA.

Splitting tensile strength

The splitting tensile strength was conducted in accordance with ASTM C49656 and results are shown in Fig. 21. The test results indicate that the addition of RA leads to a greater decline in splitting tensile strength compared to controlled mix, due to lesser strength of untreated RA. In contrast, the replacement of MRA enhanced the splitting tensile strength of concrete. A few studies have explored MPC as a surface modifier, but its effect on concrete properties remains underexplored. Verifying data accuracy is crucial, as multiple factors influence MPC-treated aggregates. To assess these interdependencies, linear regression analysis was conducted, with compressive strength as the primary independent parameter. Figure 22 illustrates the linear relationship between the splitting tensile strength and compressive strength of the concrete samples at 7th and 28th days. The coefficients of determination (R2) were 0.9032 and 0.885 respectively, demonstrating a strong correlation between two properties.

Abrasion resistance test

The abrasion resistance was conducted in accordance with ASTM C102757 and the results are shown in Fig. 23. These findings indicate a reduction in abrasion resistance loss when compared with RA. MRA-IV demonstrated an abrasion resistance loss like that of the control mix concrete, highlighting a significant improvement in its wear resistance and durability. Also, MRA-I, II and III exhibits greater abrasion resistance.

Flexural tensile strength

The results of the flexural tensile strength of the concrete mix trials are shown in Fig. 24, where test was conducted in accordance with58. The results indicate that adding 50% RA causes a 10% reduction in the flexural tensile strength compared to NA concrete. The incorporation of MRA enhanced the flexural tensile strength of concrete by 5, 10, and 18%. Figure 25 illustrates the linear relationship between the flexural tensile strength and compressive strength at the 7th and 28th days respectively. The coefficients of determination (R2) were 0.9988 and 0.9982, respectively, demonstrating a strong correlation between compressive strength and flexural tensile strength, it matches with several past studies59,60.

To analyse the maximum replacement level of MRA, a further study was conducted using only MRA-IV as a replacement for NA. Where the replacement ranges from 60 to 100% and 70% replacement is found as the maximum permissible replacement. Tables 6 and 7 illustrate the results obtained on 7th and 28th days of the testing.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA at a 5% confidence level to determine whether the variation in observed properties was due to mix composition or random chance. The results showed that all p-values were below 5%, indicating that the observed variations were caused by differences in mix composition rather than random chance. Table 8 gives the clear comparison of properties.

From the above results, MRA is ideal for M-40 grade concrete applications, including paver blocks for medium-density traffic and precast concrete panels. Additionally, MPC coating is easy to apply, does not require a separate setup, and offers a sustainable solution for industrial scaling.

Conclusions

The present study adopted non-saturated and saturated surface modification as the main approaches to modify RA, and systematically evaluated the mechanical, physical, and microstructural properties of MRA to further illustrate the impact of surface modification treatments on concrete mix. Experimental investigation reveals that final setting time of MPC is largely affected by the M/P ratio, higher ratio results in the decreased final setting time of the MPC matrix. The compressive strength of the MPC paste is also affected by the WRMB/KDP ratio as lower ratio of mix results in the comparative lower strength of MPC matrix, also the water requirement of the mix is also affected by the M/P ratio. As the disposal of WRMB is a major challenge in the refractory industry, the synthesis of MPC offers a scientific approach to waste management, preventing landfilling and potential groundwater contamination. This process enables the utilization of 70–75% of the waste, converting it into a valuable product, also the present showcase the opportunity to directly coat the RA with MPC without alternation in the concrete mix. Compared with MRA-I and MRA-II, MRA-III and MRA-IV demonstrated superior improvements in physical, mechanical, and microstructural properties. MRA-IV demonstrated a 34% reduction in water absorption, a 17% improvement in specific gravity, and reductions of 16% and 17% in aggregate crushing value and aggregate impact value, respectively. M-6 concrete outperforms in terms of compressive, flexural, and splitting tensile strengths. The compressive strength of M-6 concrete is 58% greater than that of M-2 concrete. Overall, saturation of RA followed by MPC slurry blending was superior to non-saturation RA treatment. This study overcome the limitation of RA utilization beyond 25%, as present study shows up to 50% of NA can be replaced with saturation powder and slurry blending method, but in the present study curing period was observed as major constraint for the treatment, on the findings of the present study it is suggested to conduct the research progress regarding the curing period optimization. Life cycle analysis of industrial replicable model is future scope of the present study.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References:

Ferreira, R. L. S. et al. Long-term analysis of the physical properties of the mixed recycled aggregate and their effect on the properties of mortars. Constr Build Mater 274, 121796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121796 (2021).

Shi, C. et al. Performance enhancement of recycled concrete aggregate—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 112, 466–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.08.057 (2016).

Kabirifar, K., Mojtahedi, M., Wang, C. & Tam, V. W. Y. Construction and demolition waste management contributing factors coupled with reduce, reuse, and recycle strategies for effective waste management: A review. J. Clean. Prod 263, 121265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121265 (2020).

Yang, W. S., Park, J. K., Park, S. W. & Seo, Y. C. Past, present and future of waste management in Korea. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 17, 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-014-0301-7 (2015).

Ram, V. G. & Kalidindi, S. N. Estimation of construction and demolition waste using waste generation rates in Chennai, India. Waste Manag. Res. 35(6), 610–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X17693297 (2017).

Nunes, K. R. A. & Mahler, C. F. Comparison of construction and demolition waste management between Brazil, European Union and USA. Waste Manag. Res. 38(4), 415–422. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X20902814 (2020).

Verghese Ittyeipe, A., Thomas, A. V. & Ramaswamy, K. P. C&D waste management in India: A case study on the estimation of demolition waste generation rate. Mater. Today Proc. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2023.02.410 (2023).

Dimitriou, G., Savva, P. & Petrou, M. F. Enhancing mechanical and durability properties of recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 158, 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.09.137 (2018).

Chakradhara Rao, M., Bhattacharyya, S. K. & Barai, S. V. Influence of field recycled coarse aggregate on properties of concrete. Mater. Struct. Mater. Construct. 44(1), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-010-9620-x (2011).

Padmini, A. K., Ramamurthy, K. & Mathews, M. S. Influence of parent concrete on the properties of recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 23(2), 829–836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2008.03.006 (2009).

Neupane, R. P. et al. Use of recycled aggregate concrete in structural members: a review focused on Southeast Asia. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2023.2270029 (2023).

Duan, Z., Zhao, W., Ye, T., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, C. Measurement of water absorption of recycled aggregate. Materials 15, 5141. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15155141 (2022).

Al-Waked, Q., Bai, J., Kinuthia, J. & Davies, P. Enhancing the aggregate impact value and water absorption of demolition waste coarse aggregates with various treatment methods. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 17, e01267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01267 (2022).

Maduabuchukwu Nwakaire, C., Poh Yap, S., Chuen Onn, C., Wah Yuen, C. & Adebayo Ibrahim, H. Utilisation of recycled concrete aggregates for sustainable highway pavement applications: A review. Construct. Build. Mater. 235, 117444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117444 (2020).

“IS383-2016”.

Forero, J. A., de Brito, J., Evangelista, L. & Pereira, C. Improvement of the quality of recycled concrete aggregate subjected to chemical treatments: A review. Materials 15, 2740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15082740 (2022).

Saravanakumar, P., Abhiram, K. & Manoj, B. Properties of treated recycled aggregates and its influence on concrete strength characteristics. Constr. Build. Mater. 111, 611–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.02.064 (2016).

Elsharief, A., Cohen, M. D. & Olek, J. Influence of aggregate size, water cement ratio and age on the microstructure of the interfacial transition zone. Cem. Concr. Res. 33(11), 1837–1849. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0008-8846(03)00205-9 (2003).

Kong, D. et al. Effect and mechanism of surface-coating pozzalanics materials around aggregate on properties and ITZ microstructure of recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 24(5), 701–708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2009.10.038 (2010).

Huang, R. et al. Enhancing quality and strength of recycled coarse and fine aggregates through high-temperature and ball milling treatments: mechanisms and cost-effective solutions. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-024-02109-z (2024).

Zhang, H., Wei, W., Shao, Z. & Qiao, R. The investigation of concrete damage and recycled aggregate properties under microwave and conventional heating. Constr. Build. Mater. 341, 127859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127859 (2022).

Li, L. et al. Development of nano-silica treatment methods to enhance recycled aggregate concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 118, 103963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2021.103963 (2021).

Mistri, A. et al. Environmental implications of the use of bio-cement treated recycled aggregate in concrete. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 167, 105436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105436 (2021).

Vengadesh Marshall Raman, J. & Ramasamy, V. Various treatment techniques involved to enhance the recycled coarse aggregate in concrete: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 45, 6356–6363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.10.935 (2020).

Zega, C. J., Villagrán-Zaccardi, Y. A. & Di Maio, A. A. Effect of natural coarse aggregate type on the physical and mechanical properties of recycled coarse aggregates. Mater. Struct./Mater. Construct. 43(1–2), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-009-9480-4 (2010).

Kazmi, S. M. S. et al. Influence of different treatment methods on the mechanical behavior of recycled aggregate concrete: A comparative study. Cem Concr Compos 104, 103398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2019.103398 (2019).

Beytekin, H. E., Şahin, H. G. & Mardani, A. Effect of recycled concrete aggregate utilization ratio on thermal properties of self-cleaning lightweight concrete facades. Sustainability 16(14), 6056. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16146056 (2024).

Al-Bayati, H. K. A., Das, P. K., Tighe, S. L. & Baaj, H. Evaluation of various treatment methods for enhancing the physical and morphological properties of coarse recycled concrete aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 112, 284–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.02.176 (2016).

Wu, H. et al. Utilizing heat treatment for making low-quality recycled aggregate into enhanced recycled aggregate, recycled cement and their fully recycled concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 394, 132126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132126 (2023).

Wu, C. R., Zhu, Y. G., Zhang, X. T. & Kou, S. C. Improving the properties of recycled concrete aggregate with bio-deposition approach. Cem. Concr. Compos. 94, 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2018.09.012 (2018).

Ahmad, I., Shokouhian, M., Cheng, H. & Radlińska, A. Enhancement of mechanical properties and freeze-thaw durability of recycled aggregate concrete using aggregate pretreatment. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40996-024-01672-7 (2024).

Dai, X., Lian, L., Jia, X., Qin, J. & Qian, J. Preparation and properties of magnesium phosphate cement with recycled magnesia from waste magnesia refractory bricks. J. Build. Eng. 63, 105491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105491 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Effect of magnesium phosphate cement on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled aggregate and recycled aggregate concrete. J. Build. Eng. 46, 103611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103611 (2022).

Li, Y., Sun, J. & Chen, B. Experimental study of magnesia and M/P ratio influencing properties of magnesium phosphate cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 65, 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.04.136 (2014).

Wang, X., Li, X., Lian, L., Jia, X. & Qian, J. Recycling of waste magnesia refractory brick powder in preparing magnesium phosphate cement mortar: Hydration activity, mechanical properties and long-term performance. Constr Build Mater 402, 133019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133019 (2023).

Li, Y., Bai, W. & Shi, T. A study of the bonding performance of magnesium phosphate cement on mortar and concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 142, 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.03.090 (2017).

Formosa, J. et al. Magnesium phosphate cements formulated with a low-grade MgO by-product: physico-mechanical and durability aspects. Constr. Build. Mater. 91, 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.05.071 (2015).

Tam, V. W. Y., Tam, C. M. & Wang, Y. Optimization on proportion for recycled aggregate in concrete using two-stage mixing approach. Constr. Build. Mater. 21(10), 1928–1939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2006.05.040 (2007).

Tam, V. W. Y. & Tam, C. M. Assessment of durability of recycled aggregate concrete produced by two-stage mixing approach. J. Mater. Sci. 42, 3592–3602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-006-0379-y (2007).

Tam, V. W. Y., Gao, X. F. & Tam, C. M. Microstructural analysis of recycled aggregate concrete produced from two-stage mixing approach. Cem. Concr. Res. 35(6), 1195–1203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.10.025 (2005).

Huang, Y., Wang, J., Ying, M., Ni, J. & Li, M. Effect of particle-size gradation on cyclic shear properties of recycled concrete aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 301, 124143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124143 (2021).

Park, J. W., Kim, K. H. & Ann, K. Y. Fundamental properties of magnesium phosphate cement mortar for rapid repair of concrete. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 7179403. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7179403 (2016).

B. of Indian Standards, IS 8041 (1990): Specification for rapid hardening Portland cement.

B. of Indian Standards, IS 4031-5 (1988): Methods of physical tests for hydraulic cement, Part 5: determination of initial and final setting times (2002).

Designation: C 150-07 Standard Specification for Portland Cement 1. Available: www.astm.org.

Designación: ASTM C 136-01 Método de Ensayo Normalizado para determinar el Análisis Granulométrico de los Áridos Finos y Gruesos.

Standard Test Method for Specific Gravity and Absorption of Coarse Aggregate 1.

Test Method for Relative Density (Specific Gravity) and Absorption of Fine Aggregate (ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1520/C0128-15.

Li, Y. & Chen, B. Factors that affect the properties of magnesium phosphate cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 47, 977–983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.05.103 (2013).

Fang, B. et al. Research progress on the properties and applications of magnesium phosphate cement. Ceram. Int. 49, 4001–14016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.11.078 (2023).

Gelli, R. et al. Effect of borax on the hydration and setting of magnesium phosphate cements. Constr Build Mater 348, 128686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128686 (2022).

Zheng, Y., Zhou, Y., Huang, X. & Luo, H. Effect of raw materials and proportion on mechanical properties of magnesium phosphate cement. J. Road Eng. 2, 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jreng.2022.06.001 (2022).

310037688-ASTM-C109.

Patil, Y. R., Dakwale, V. A. & Ralegaonkar, R. V. Recycling construction and demolition waste in the sector of construction. Adv. Civ. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1155/2024/6234010 (2024).

Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens (ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2009) https://doi.org/10.1520/C0039_C0039M-09A.

Splitting Tensile Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens 1. Available: www.astm.org.

778039133-ASTM-C1027.

Test Method for Flexural Strength of Concrete (Using Simple Beam with Third-Point Loading) (ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1520/C0078_C0078M-18.

Cabral, A. E. B., Schalch, V., Molin, D. C. C. D. & Ribeiro, J. L. D. Mechanical properties modelling of recycled aggregate concrete. Construct. Build. Mater. 24, 421–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2009.10.011 (2010).

Shaban, W. M. et al. Effect of pozzolan slurries on recycled aggregate concrete: Mechanical and durability performance. Constr Build Mater 276, 121940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121940 (2021).

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yuvraj Rajesh Patil: Manuscript writing and reviewing, methodology, conceptualization Vaidehi A. Dakwale: Editing and reviewing the manuscript, supervision Rahul V. Ralegaonkar: Editing and reviewing the manuscript, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Patil, Y.R., Dakwale, V.A. & Ralegaonkar, R.V. Treatment of recycled concrete aggregate with magnesium phosphate cement. Sci Rep 15, 40669 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03328-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03328-6