Abstract

Cancer is one of the most perilous diseases worldwide, often incurable if not diagnosed in its early stages. Among cancers, breast cancer ranks as the second most lethal, particularly affecting women and contributing to a significant number of fatalities. This work analyzes the breast cancer model in the fractional scenario by incorporating the therapy and prevention diagnosis. The model is subjected to theoretical and numerical investigations to explore the dynamics and predictions of the disease. Furthermore, optimal disease control is presented along with a sensitivity analysis of model parameters. Furthermore, the obtained results are compared with the real data with varying fractional orders, revealing that most of the data points coincide with the fractional order 0.98.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is characterized by the uncontrolled proliferation of abnormal cells within the tissues of breast that results in disrupting cell division1. Such increase disturb the genes which are responsible for the growth and division of cells that results in rising masses or lumps related to breast cancer2. Based on the data and findings proposed in “The Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration” breast cancer shows the top existence ratio amongst all the other types of cancers3,4.

According to the measurement by disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) among females around the world, breast cancer has major crucial impact in a negative way on women’s health in comparison to other types of cancer which demonstrates that due to disability, premature death and illness, breast cancer leads to loss of more time of healthy life5. Raising awareness of breast cancer risk factors among women globally is essential for promoting early detection and prevention strategies. Particular risk factors like age, family history, genetic mutation, lifestyle among others can escalate the risks of a woman’s chance of having breast cancer6. Though the existence of these risk elements do not guarantee suffering from breast cancer. In order to avoid the risks of breast cancer, awareness of modifiable risk factors may contribute to early detection and improved outcomes.

”Based on a survey conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO), breast cancer was ranked as the second most widespread cancer, presently breast cancers is considered as the most widespread cancer among women around the world. Based on the data collected in a survey by WHO, globally 8 to 9 percent of the females will be diagnosed with breast cancer at some stage in their life spans. Despite extensive research, the etiology of breast cancer remains only partially understood and is still a puzzle7. Based on the investigations carried out in7 and8, among all the cancers the most common cancer diagnosed in women worldwide is breast cancer that is reported in approximately 2.3 million novel cases in 2020 by WHO breast cancer. Breast cancer is marked as the major cause of death and resulted in deaths of 685,000 women around the world, diagnosed in 2.3 million women9.

In recent decades, significant progress has been made in understanding the development, diagnosis, metastasis, and treatment of breast cancer10. In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) breast cancer has emerged as the most frequently diagnosed cancer and a leading cause of cancer related deaths12. Several researchers have studied various dynamics of the breast cancer . For instance, Donahue et al., have presented their work in prevention as well as treatment of lymphedema related to breast cancer13.Zhang and colleagues developed a hybrid delivery system combining cancer-derived small extracellular vesicles with liposomes for targeted breast cancer treatment14. He et al. explored advancements in chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy for breast cancer treatment15.

Over the past decades, fractional operators are widely employed in disease analysis which can predict more accurately the risks of disease due to their non-local nature. For instance, Huanglongbing disease model with fractional operators is studied in16. Bifurcations, stability and other complex dybnamics of Cancer model is presented in17. Oscillatory and complex dynamics of HIV-1 are studeied in18. In similar way Rota virus disease with fractional operators is demonstrated in19.The transmission dynamics of water-borne diseases using nonlocal fractional operators is examined in20. A fractional-order model for viral infection with control strategies is analyzed in21. The study in22 explores the fractional dynamics of infectious diseases under preventive measures. Lymphatic filariasis dynamics using fractional calculus is presented in23. A fractional model incorporating vaccination and carrier effects for typhoid fever is discussed in24. Tuberculosis dynamics with various control strategies using real data is studied in25. An SIR-type fractional delay model using Mittag–Leffler kernels is explored in26. Brucellosis disease modeling under vaccination in a fractional context is covered in27. Similarly, a new fractional-order model for vaccination strategies is proposed in28.

Model formulation

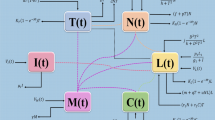

This work enhaces the study on the breast cancer disease by incorporating fractional Caputo’s operator, with an an effecient numerical scheme. The model considered in this work is presented by29, and can be observed as follows:

With initial values \(\mathcal {H}(0)\ge \mathcal {H}_{0}, ~\mathcal {P}(0)\ge \mathcal {P}_{0},~\mathcal {I}(0)\ge \mathcal {I}_{0},~\mathcal {F}(0)\ge \mathcal {F}_{0},~\mathcal {E} \ge \mathcal {E}_{0}\). The above model consists of five compartments, which are classified on the basis of the epidemiology of breast cancer. \(\mathcal {H}\) represents the population who are admitted to the hospital because of the cancer effects. \(\mathcal {P}\) contains the population who are suffering from stage 3. \(\mathcal {I}\) contains those individuals suffering from stage 4 cancer. \(\mathcal {F}\) contains disease free population after being undergone chemotheraphy. Finally, \(\mathcal {E}\) contains the individuals who are suffering from cancer and have cardiotoxicity. The parameters description is presented in Table 1.

In fractional form the model (1) can be expressed as:

Where \(\alpha _{1}\) is fractional order and lies in \(0<\alpha \le 1\) and C represents Caputo’s operator.

Preliminaries

Here we present the basic concept of nonlocal operators. Let \(\varpi\) and \(\beta _{2}\) represent denote the fractional and fractal order, respectively. For a continuous and fractal differentiable function \(\textrm{p}(\varvec{t})\) on \(\left( \text {m},\text {n}\right) ,\) we provide the following definitions of nonlocal operators in Caputo’s sense.

Definition 2.1

17 Let \(\varphi\) be a continuous function on \([0,\mathbb {T}]\). The Caputo fractional derivative may be expressed as:

where \(n=\lfloor {\alpha }_{1}\rfloor +1\) and \(\lfloor {\alpha }_{1}\rfloor\) represents the integers part of \({\alpha }_{1}\).

Definition 2.2

17 The Caputo fractional integral is defined as:

Theoretical examination of the fractional order system (2)

Here, we will explore all the required aspects( i-e Theoretical and Computational) of the system (2) under consideration. Let us consider \(\mathfrak {B}(\mathfrak {A})\) be a Banach-space with sub-norm, for \(\mathfrak {A}=[0,T].\) For our given model, suppose \(\mathscr {P}=\mathcal {P}(\mathfrak {A})\times \mathcal {P}(\mathfrak {A})\times \mathcal {P}(\mathfrak {A})\times \mathcal {P}(\mathfrak {A})\) assume the Banach-space equipped with a norm:

where \(\left\| \mathcal {H}\right\| =\sup _{t\in \mathbb {A}}\left| \mathcal {H}(t)\right| ,\left\| \mathcal {I}\right\| =\sup _{t\in \mathbb {A}}\left| \mathcal {I}(t)\right| ,\left\| \mathcal {P}\right\| =\sup _{t\in \mathbb {A}}\left| \mathcal {P}(t)\right| , \left\| \mathcal {F}\right\| =\sup _{t\in \mathbb {A}}\left| \mathcal {F}(t)\right| .\) and \(\left\| \mathcal {E}\right\| =\sup _{t\in \mathbb {A}}\left| \mathcal {E}(t)\right| .\)

The proposed model (2) can present as

where

The corresponding form of the Eq. (3) is

Furthermore, we need to prove that the given kernels satisfy Lipschitz conditions. For that lets take the 1st equation.

where \(c_{1}\) is a Lipschitz constant, such that \(c_{1}\ge 0\). Thus \(\left\| \mathfrak {D}_{1}(\nu ,\mathcal {H})-\mathfrak {D}_{1}(\nu ,\mathcal {H}_{1})\right\| \le c_{1}\left\| \mathcal {H}-\mathcal {H}_{1}\right\|\).

Similarly we can do the same for other equations in system (4): where \(c_{2}=(\phi _{2}+\beta _{1}+\tau _{1}+\mu _{1}),~c_{3}=(\phi _{3}+\tau _{2}+\mu _{2}),~c_{4}=(\psi _{1}+\psi _{2}+\tau _{3})\), and \(c_{5}=(\mu _{3})\) are Lipschitz constants.

Since \(c_{i}\in [0,1)\), for \(i=1,2,3,4,5.\) Therefore all the considered kernels \(\mathfrak {D}_{1},\mathfrak {D}_{2},\mathfrak {D}_{3},\mathfrak {D}_{4}\) and \(\mathfrak {D}_{5}\) fulfill the contraction condition. Now, the system can write (5) recursively as:

So the alteration between each pair of successive terms of system (6) is given as :

Taking norm of the 1st equation of (7), we get

Similarly, we can do the same for the remaining equations in (7) as

The above equation can be written as:

Next we have to prove the unique solution for our considered model. To prove the uniqueness of solution , suppose that \(\frac{\textrm{p}^{\varpi }\gamma _{i}}{\Gamma (\varpi )}<1,\) for \(t\in [0,\textrm{T}]\) and \(i=1,2,3,4,5.\) let (8) and (9) and by employing Lipschitz continuity property of the kernels and recursive technique, the result is:

By the use of triangle inequality and (11), we get:

where \({\kappa }_{i}=\left[ \frac{1}{\Gamma (\varpi )}\gamma _{i}\textrm{p}^{\varpi }\right] ^{l}<1,\,i=1,2,3,4.\) Hence Cauchy sequences \(\mathcal {H}_{l},\mathcal {I}_{l},\mathcal {P}_{l},\mathcal {F}_{l}\) are in the Banach-space \(\mathcal {P}(\mathfrak {A}).\) From Eq. (12) we conclude their convergency. So the proposed fractional order system has a unique solution.

Hyers-Ulam stability

In this portion, we Analyze the Hyers-Ulam and general Hyers-Ulam stability analysis32,33. Let us suppose \(\epsilon >0\) with,

for \(\epsilon =\max (\epsilon _{i})^T, i=1,2,3.\)

Definition 3.1

Equation (4) is supposed to be Hyers-Ulam stable such that \(\exists , \mathfrak {H}_{\mathfrak {P}}>0,\) for any \(\epsilon >0\) and for all solution \(\mathfrak {S}\in \mathcal {Y}\) of (4) and (13), has unique solution \(\widetilde{\mathfrak {S}}\in \textbf{Y}\) which satisfy

where \(\mathfrak {H}_{\mathfrak {P}}=\max (\mathfrak {H}_{\mathfrak {P}_i})^T,\ i=1,2,3.\)

Now for the generalized Hyers-Ulam stability we have,

Definition 3.2

Equation (4) is generalized Hyers-Ulam stable if for a continuous function \(\varphi :\mathbb {R}^+\rightarrow \mathbb {R}^+\) with \(\varphi (0)=0\), such that for all solution \(\mathfrak {S}\in \mathcal {Y}\) of (4), there is one solution \(\widetilde{\mathfrak {S}}\in \mathcal {Y}\) which holds the given relation

where \(\varphi _{\mathcal {P}}=\max (\varphi _{\mathcal {P}_i})^T,\ ,\ i=1,2,3.\)

Remark 1

An independent function \(\varphi\) of \(\mathfrak {S}\in \mathcal {Y}\), one has

-

(I)

\(|\varphi (t)|\le \epsilon ,\ ~ \varphi =\max (\varphi _i), ~ t\in \textrm{J}, \ i=1,2,3.\)

-

(II)

\(^{\mathcal {C}}\textbf{D}_{t}^{\alpha _{1}}\mathfrak {S}(t)=\mathcal {P}(t, \mathfrak {S}(t))+\varphi (t), ~ t\in \textrm{J}.\)

Lemma 3.2.1

The solution of unsettled problem

holds the inequality

Proof

Utilizing Lemma 3.2.1, the solution of (16), become

From the helpful Remark 1, the result (17) give in

\(\square\)

Theorem 1

From supposition \((\mathbf {\mathfrak {C}_1})\) and if \(1-\Psi \mathcal {L}_{\mathfrak {P}}>0\), then form Lemma 3.2.1, the result of (4) is Hyers-Ulam and generalized Hyers-Ulam stable as well.

Proof

Assume that \(\mathfrak {S} \in \mathcal {Y}\) be any arbitrary solution and \(\widetilde{\mathfrak {S}}\in \mathcal {Y}\) is one solution of (4), then using \((\textbf{C}_1)\) one has

After simplifying (19),

From the above Eq. (20), may be written as

Hence, using \(\varphi _{\mathfrak {P}}(\epsilon )=\mathfrak {H}_{\mathfrak {P}}\epsilon\) with \(\varphi _{\mathfrak {P}}(0)=0\), we summarize that the result of the proposed model (4) is Hyers-Ulam stable and generalized Hyers-Ulam. \(\square\)

Computational investigation of the system (2)

Here we prove the numerical-scheme for the proposed model (2). Our proposed model is non linear, and it is difficult to solve analytically therefore we use numerical approaches of Newton polynomial. Now, consider

At \(t_{{\mu }+1}=({\mu }+1)\nu t,\) the aforementioned system can be presented as:

Then, we get:

For the approximation of the kernels \(\mathfrak {D}_{1}(\nu ,\mathcal {H}),\mathfrak {D}_{2}(\nu ,\mathcal {H}),\mathfrak {D}_{3}(\nu ,\mathcal {H}),\mathfrak {D}_{4}(\nu ,\mathcal {H}),\) we will use the Newton polynomial as:

Upon putting the Newton polynomials in the system (22), we get:

Now, we focusing on the first equation from (23), we have

Now, we evaluate the integrals of system (24).

Using the above values of in Eq.(24), we get

Likewise, for the remaining classes of Eq.(23), we get

Equations (25)–(28) are the solutions of the proposed model. To evaluate the accuracy of the derived scheme, we demonstrate that

Consider the first equation of considered model as:

After some steps, one can get

The error term \(\mathcal {T}_{1}^{\varpi }\)can be written as

Now

where \(\epsilon _{l}\) represent a constant which would be derive through using Taylor series approximation. Now, we assess the integral:

Now

therefore

using \(t_{{\mu }+1}>\nu .\) We have

Thus

Then

and

Using above equations, we have

Thus, Eq.(34) becomes

In the same way, we can derive the last three inequalities of Eq.(34).

Optimal control analysis of the proposed model

This part presents the optimal control analysis of the breast cancer model which is considered with Caputo fractional derivative of order \(0 < \alpha _1 \le 1\) to incorporate the memory effects inherent in cancer progression and treatment response. The system of equations is considered earlier is given by:

Control objectives and admissible set

The goal is to determine optimal time-dependent control strategies \(u_1(t)\) (therapy intensity) and \(u_2(t)\) (early diagnosis and prevention), that minimize the cost functional:

where \(A_i\) and \(B_i\) are positive constants representing weights for health outcomes and control efforts respectively. The control functions must satisfy:

Let the admissible control set be:

Hamiltonian and Pontryagin’s maximum principle

To apply the Pontryagin Maximum Principle (PMP), we define the Hamiltonian \(\mathcal {H}\):

The adjoint system is given by:

For example, the equation for \(\lambda _1(t)\) becomes:

Characterization of optimal controls

The optimal controls that minimize the Hamiltonian are characterized by:

where

Existence of optimal control

Theorem 2

(34,35) Suppose the admissible control set \(\mathcal {U}\) is non-empty, convex, and closed in \(L^2(0,T)^2\), the integrand of the cost functional \(J(u_1, u_2)\) is convex with respect to the control variables \((u_1, u_2)\), and the right-hand side of the fractional state system is linearly bounded (or Lipschitz continuous) in \((u_1, u_2)\). Then, there exists at least one optimal control pair \((u_1^*, u_2^*) \in \mathcal {U}\) that minimizes the cost functional \(J(u_1, u_2)\) over the time interval [0, T].

Proof

The proof relies on a direct method in the calculus of variations and is adapted from classical results in optimal control theory [?], extended to systems involving Caputo fractional derivatives.

We verify the following conditions that guarantee the existence of an optimal control:

-

1.

Convexity and Closedness of the Control Set. The admissible set

$$\begin{aligned} \mathcal {U} = \left\{ (u_1, u_2) \in L^2(0,T)^2 \mid 0 \le u_i(t) \le u_{i,\max } \text { a.e. on } [0,T],\ i = 1,2 \right\} \end{aligned}$$is convex, closed, and bounded in \(L^2\). Since \(\mathcal {U}\) is defined by pointwise bounds on measurable functions, it is also weakly sequentially compact.

-

2.

Lipschitz Continuity of the State Equations. The right-hand side of the state system is affine in \(u_1(t)\) and \(u_2(t)\). Terms such as

$$\begin{aligned} -(1 + u_2(t))(\phi _1 + \beta _1) H(t) \end{aligned}$$and similar expressions for P(t), I(t), F(t) demonstrate that the system is Lipschitz in the controls. This ensures the continuity of the state trajectory with respect to control variations.

-

3.

Well-Posedness of the State System. Under the assumptions made earlier in the paper, the fractional-order Caputo system has a unique solution for any admissible control pair \((u_1, u_2) \in \mathcal {U}\).

-

4.

Convexity of the Cost Integrand. The running cost

$$\begin{aligned} L(x(t), u(t)) = A_1 H(t) + A_2 P(t) + A_3 I(t) + A_4 E(t) + B_1 u_1^2(t) + B_2 u_2^2(t) \end{aligned}$$is convex in the controls due to the quadratic terms \(u_1^2\) and \(u_2^2\), and linear in the state variables.

-

5.

Lower Semi-Continuity. The cost functional \(J(u_1, u_2)\) is weakly lower semi-continuous in \(L^2\) as it is the integral of a convex and continuous function in \(u_1\) and \(u_2\).

By invoking the Filippov-Cesari theorem for optimal control34, which ensures the existence of optimal controls under these structural assumptions, we conclude that there exists an optimal pair \((u_1^*, u_2^*) \in \mathcal {U}\) such that

\(\square\)

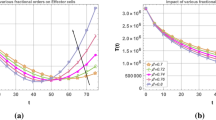

Figure 1 shows the temporal evolution of the individuals in system state (\(\mathcal {P}\)) and (\(\mathcal {I}\)) under two scenarios: with and without control. The fractional-order is considered as \(\alpha _1 = 0.97\), which we know accounts for memory effects in the progression of disease, an important consideration for chronic illnesses such as cancer. The parameters used during simulation are in the form \(A_1 = 1\), \(A_2 = 0.9\), \(A_3 = 1\), \(A_4 = 1\), \(B_1 = 1\), \(B_2 = 1\), \(u_1 = 0.9\), and \(u_2 = 0.9\).

In left panel (a), the evolution of \(\mathcal {P}\), representing those diagnosed with stage 3 breast cancer, is demonstrated. With no control intervention, we see that the number of individuals in grows steadily, reaching peak of over \(8 \times 10^4\) by \(t = 100\). On the other hand, with control, the growth of \(\mathcal {P}\) slows considerably. The population reaches maximum number around \(t = 80\) and then begins to decline. This shows that the interventions are effective in either reversing the condition or preventing further progression.

The right panel (b) demonstrates the progression of \(\mathcal {I}\). In the absence of control mechanisms, the population having stage 4 cancer increases sharply, approaching \(1.8 \times 10^5\) by time \(t = 100\). Contrary to this, the use of control reduces the number significantly, which maintains it below \(1.3 \times 10^5\) over the same time period. This indicates that the control not only decreases the number of individuals transitioning from earlier stages but also possibly slows the worsening of the disease once individuals reach stage 3. The effectiveness of control in managing late-stage cancer progression is crucial for enhancing survival rates and reducing the long-term burden on healthcare systems.

Sensitivity analysis of model parameters

To quantify the influence of key parameters on the progression of breast cancer in our fractional-order model, we conduct a local sensitivity analysis. This method helps identify which parameters most significantly affect critical clinical outcomes such as the population in stage 3 (\(P(t)\)), stage 4 (\(I(t)\)), and cardiotoxicity-affected class (\(E(t)\)).

Let \(O(t)\) denote a model output of interest (e.g., the peak value of \(P(t)\) over a simulation period). For a parameter \(p_i\), the normalized sensitivity index is defined as:

This derivative is approximated numerically using the centered difference formula:

where \(\Delta p = \epsilon p_i\), and \(\epsilon = 0.01\) represents a 1% perturbation.

We apply this procedure to each of the following parameters: \(\beta _1, \beta _2, \phi _1, \phi _2, \phi _3, \tau _1, \tau _2, \tau _3, \mu _1, \mu _2, \mu _3\). The outputs \(P(t)\), \(I(t)\), and \(E(t)\) are tracked over the simulation horizon, and their peak values are recorded for each parameter perturbation.

Figure 2 shows normalized sensitivity indices for peak values of \(\mathcal {P}(t)\), \(\mathcal {I}(t)\), and \(\mathcal {E}(t)\). These indices give insight into how small perturbations in parameters of the considered model influence the peak burden, which is also visualized in the next section separately. The fractional-order is considered as 0.97, and perturbation parameter as \(\epsilon = 0.01\). From the figure, it is obvious that some of the parameters have more pronounced effect on specific populations. For example, \(\phi _3\) and \(\mu _2\) shows strong negative sensitivity for all the states under consideration, particularly impacting \(\mathcal {I}(t)\) and \(\mathcal {E}(t)\). This in turn shows that, small increase in these parameters considerably reduce the number of individuals in these categories. Biologically, this indicates that parameters linked to treatment efficiency or natural recovery are critical in controlling disease progression and associated complications.

The parameter \(\tau _3\), also depicts considerable negative impact on \(\mathcal {I}(t)\) and \(\mathcal {E}(t)\), but to a lesser extent on \(\mathcal {P}(t)\). In contrast, \(\psi _1\) and \(\psi _2\), shows relatively high positive effect for \(\mathcal {P}(t)\) and \(\mathcal {E}(t)\), suggesting that minor increase could elevate the burden of disease. Interestingly, \(\beta _1\) and \(\beta _2\) exhibit mixed response. \(\beta _1\) positively affects \(\mathcal {P}(t)\) but has subdued effect on \(\mathcal {I}(t)\) and \(\mathcal {E}(t)\).

Overall, the sensitivity analysis highlights the differential influence of model parameters on each disease compartment, reinforcing the need for targeted intervention strategies.

Numerical illustrations of fractional order system (2)

This part is responsible for the visualization of the obtained numerical results with the proposed scheme of the suggested model (2), with a variety of fractional orders as with varying the important parameters. The time interval is considered to be [0-120] with the step size \(dt=0.01\). The initial values are considered to be of the form \(\mathcal {H}(0)=30{,}000,~\mathcal {P}(0)=12{,}300,~\mathcal {I}(0)=738,~\mathcal {F}(0)=334,~\mathcal {E}(0)=10\). The parameters presented in Table 1 are used during the simulations, while some important parameters are varied which are mentioned in the captions of the figures. Figure 3 shows the behavior of \(\mathcal {H}\) and \(\mathcal {P}\), Fig. 4 shows the behavior of \(\mathcal {I}\) and \(\mathcal {F}\), and finally Fig. 5 presents the behavior of \(\mathcal {E}\) with various fractional orders. The dynamics of the state variable \(\mathcal {H}\) are presented in Fig. 3a. Where it can be observed that the number of individuals hospitalized and are diagnosed to be cancer patients is increasing then after \(t=120\) becomes stable, while at lower fractional orders the number of individuals in \(\mathcal {H}\) becomes stable as soon as \(t=25\). The evolution of the state variable \(\mathcal {P}\), is demonstrated in the Fig. 3b, with a variety of fractional orders. We see in Fig. 3b, that those people suffering from the cancer with stages \(3\mathcal {H}\) and \(3\mathcal {P}\) are decresing sharply at the beginning, while increase in number is observed as the time passes and become stable at \(t=25\) with fractional order 0.70. Furthermore figures 4a and 4b, depict the evolution of the individuals in classes \(\mathcal {I}\) and \(\mathcal {F}\), respectively. From Fig. 4a, it is revealed that individuals suffering from stage 4 cancer are increasing with time and then turn towards stability faster with small values of \(\alpha _1\). Furthermore, Fig. 4b shows that the people becoming disease free with chemotherapy increases with time. Similarly, Fig. 5 shows the dynamics of the state variable \(\mathcal {E}\), where it can be seen that the number of people cardiotoxic patients increases with time. The lower fractional orders are responsible for the system state variables to get to the stable points soon as compared to higher values of \(\alpha _1\).

The population dynamics of \(\mathcal {H}\) and \(\mathcal {P}\) of the system (2) with various fractional orders assumed as [(blue,0.99),(green,0.90),(red,0.80),(cyan,0.70)].

The population dynamics of \(\mathcal {I}\) and \(\mathcal {F}\) of the system (2) with various fractional orders assumed as [(blue,0.99),(green,0.90),(red,0.80),(cyan,0.70)].

The population dynamics of \(\mathcal {E}\) of the system (2) with various fractional orders assumed as [(blue,0.99),(green,0.90),(red,0.80),(cyan,0.70)].

Disease dynamics with varying parameters in different stages

This part of the present work is devoted to observe the influence of different parameters on different state variables of the system, to observe whether by increasing certain parameter increases the number of population in a specific class or it influence otherwise. The fractional order is considered to be \(\alpha _{1}=0.90\) for the following simulations. Therefore, first we consider a variety of values for the recovery rate at stages (1 and 2) due to the chemotheraphy represented with \(\phi _{1}\) demonstrated in Fig. 6. We considered the values to be 0.03, 0.06, 0.09, 0.12 and observed from the figure that when the more people are recovered at stages 1 and 2, then there the number of patients decreases which is very important and useful. Figures 6a,b, show that the number of the individuals in \(\mathcal {H}\) and \(\mathcal {P}\) decreases as the chemotherapy is increased. Furthermore, Fig. 6c–e, visualize that the number of individuals in \(\mathcal {I}\), \(\mathcal {F}\) and \(\mathcal {E}\) increases as the value of the \(\phi _{1}\) increases. In these figures, we see that increasing the \(\phi _{1}\) increases the individuals suffering from stage 4, but at the same time it can be seen that it increases the number of those who are recovered from the disease. Next, we observe the influence of the rate of recovery at stage 4 with chemotheraphy. The values for the parameter \(\phi _{3}\), are considered as 0.01, 0.03, 0.05, 0.07. From the Fig. 7, we see that there is decrease in the number of the individuals suffering from stage 4 cancer as the chemotheraphy at stage 4 is increased such that when the value of \(\phi _{3}\) is high as can be observed in Fig. 7a. Further, we see that the more population is recovered as the chemotheraphy increases at stage 4. Figure 8a, shows the dynamics of the influence of the cardiotoxicity caused by intensive chemotheraphy \(\tau _{1}\) on \(\mathcal {P}\), \(\mathcal {I}\) and \(\mathcal {F}\). From the Fig. 8, it can be seen that with increase in \(\tau _{1}\), directly decreases the population in the presented state variables. The influence of increased cardiotxicity in patients at stage 4 chemotheraphy \(\tau _{2}\), is demonstrated in the Fig. 9 with values considered as 0.05, 0.10, 0.15, 0.20. Figure 9 shows that increasing \(\tau _{2}\), increases the number of individuals in \(\mathcal {E}\), while a decrease is observed in the populations of \(\mathcal {I}\) and \(\mathcal {F}\), showing that less people will recovered from the disease.

The population dynamics of the influence of \(\phi _{1}\) on different state variables of the system (2) with values of \(\phi _{1}\) assumed to be [(blue,0.03),(green,0.06),(red,0.09),(cyan,0.12)].

The population dynamics of the influence of \(\phi _{3}\) on different state variables of the system (2) with values of \(\phi _{3}\) assumed to be [(blue,0.01),(green,0.03),(red,0.05),(cyan,0.07)].

The population dynamics of the influence of \(\tau _{1}\) on different state variables of the system (2) with values of \(\tau _{1}\) assumed to be [(blue,0.03),(green,0.06),(red,0.09),(cyan,0.12)].

The population dynamics of the influence of \(\tau _{2}\) on different state variables of the system (2) with values of \(\tau _{2}\) assumed to be [(blue,0.05),(green,0.10),(red,0.15),(cyan,0.20)].

The comparison of the real cases with the simulated results for the time period of 2004-2016 in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia of the system (2) with values of \(\alpha _{1}\) assumed to be [(blue,0.99),(green,0.98),(red,0.97),(cyan,0.96)].

The comparison of the real and the simulated results with various fractional orders is visualized in the Fig. 10 considered from31. The time considered here is in [0, 12] with step size 0.01. The data is for the period of 12 years such that from 2004-2016. From the comparison it is revealed that most of the data points coincides with that of the simulated results with fractional order \(\alpha _{1}=0.98\), which shows that these operators have the property to better predict the cancer disease. The closeness of the fit at this particular fractional order highlights the predictive capability and practical relevance of the proposed model. This also supports the use of fractional calculus in modeling long-term dynamics of complex diseases such as cancer, where non-local effects behavior play a crucial role.

Conclusion

Breast cancer, the second most lethal disease according to WHO which affects women and is the main of mortality of many individuals. This work successfully analyzed the breast cancer model with fractional operator subjected to the therapy and prevention diagnosis. The theoretical and numerical investigations are carried out and the dynamics and predictions of the disease are analyzed and discussed. Furthermore, the optimal control analysis and sensitivity analysis of the parameters are presented. Similarly, the results are simulated with a various fractional orders and the influence of several useful parameters is also studied. Moreover, the obtained results are compared with the real data, where good agreements are obtained. Finally, we have properly discussed the obtained results. From the results we observed that, escalating chemotherapy levels during early stages exhibit a dual effect: a decline in patient numbers alongside an increase in recoveries. Conversely, heightened chemotherapy at stage 4 showcases a promising reduction in stage 4 patients, coupled with notable improvements in recovery rates.

The study uncovers the nuanced impact of cardiotoxicity on affected classes within the population. Elevated levels of cardiotoxicity, particularly in intensive chemotherapy scenarios, demonstrate a significant decrease in population counts within the relevant classes. Interestingly, when examining intensified cardiotoxicity at stage 4, the findings reveal a concerning trend, while there is an uptick in individuals within the class denoted as \(\mathcal {E}\), indicative of a more advanced disease stage, there is a simultaneous decrease in populations within classes \(\mathcal {I}\) and \(\mathcal {F}\), hinting at compromised recovery prospects for affected patients.

Future work could focus on optimizing chemotherapy protocols by incorporating personalized approaches and integrating novel treatment modalities like targeted therapies or immunotherapies. Longitudinal studies tracking patient outcomes over time could provide insights into the long-term efficacy and sustainability of current treatment strategies. Collaborations across disciplines and leveraging advanced technologies can further refine cancer care for improved patient outcomes.

Data availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/basic_info/what-is-breastcancer.html.

Basic Information About Breast Cancer. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/basic_info/index.html.

Fitzmaurice, C. et al. The global burden of cancer 2013. JAMA Oncol. 1, 505–527 (2015).

Fathoni, M. I. A., Gunardi; Kusumo, F. A., & Hutajulu, S. H. Mathematical model analysis of breast cancer stages with side effects on heart in chemotherapy patients. AIP Conf. Proc. 2192, 060007 (2019).

Ganz, P. A., Greendale, G. A., Petersen, L., Kahn, B. & Bower, J. E. Breast cancer in younger women: reproductive and late health effects of treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 21(22), 4184–4193 (2003).

Bodai, B. I. & Tuso, P. Breast cancer survivorship: a comprehensive review of long-term medical issues and lifestyle recommendations. Permanente J. 19(2), 48 (2015).

Breast Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer (accessed on 13 April 2023).

DeSantis, C. E. et al. International variation in female breast cancer incidence and mortality ratesinternational variation in female breast cancer rates. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 24, 1495–1506 (2015).

Arnold, M., Morgan, E., Rumgay, H., Mafra, A., Singh, D., Laversanne, M., Vignat, J., et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. The Breast66, 15–23 (2022).

Chavda, V. P., Nalla, L. V., Balar, P., Bezbaruah, R., Apostolopoulos, V., Singla, R. K., Khadela, A., Vora, L., & Uversky, V. N. Advanced phytochemical-based nanocarrier systems for the treatment of breast cancer. Cancers15(4), 1023 (2023).

Houghton, S. C. & Hankinson, S. E. Cancer progress and priorities: breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 30, 822–844 (2021).

Alqahtani, W. S. et al. Epidemiology of cancer in Saudi Arabia thru 2010–2019: A systematic review with constrained meta-analysis. AIMS Public Health 7, 679 (2020).

Donahue, P., MacKenzie, A., Filipovic, A. & Koelmeyer, L. Advances in the prevention and treatment of breast cancer-related lymphedema. Breast Cancer Res. Treatm. 200(1), 1–14 (2023).

Zhang, W., Ngo, L., Tsao, S.C.-H., Liu, D. & Wang, Y. Engineered cancer-derived small extracellular vesicle-liposome hybrid delivery system for targeted treatment of breast cancer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15(13), 16420–16433 (2023).

He, Q. et al. Advances in chimeric antigen receptor T cells therapy in the treatment of breast cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 162, 114609 (2023).

Xu, C. et al. Analysis of Huanglongbing disease model with a novel fractional piecewise approach. Chaos Solitons Fract. 161, 112316 (2022).

Xuan, L. et al. Bifurcations, stability analysis and complex dynamics of Caputo fractal-fractional cancer model. Chaos Solitons Fract. 159, 112113 (2022).

Ahmad, S., Ullah, A., Partohaghighi, M., Saifullah, S., Akgül, A., & Jarad, F. Oscillatory and complex behaviour of Caputo-Fabrizio fractional order HIV-1 infection model. (2022).

Naowarat, S., Ahmad, S., Saifullah, S., De la Sen, M. & Akgül, A. Crossover dynamics of Rotavirus disease under fractional piecewise derivative with vaccination effects: Simulations with real data from Thailand, West Africa, and the US. Symmetry 14(12), 2641 (2022).

Deebani, W., Jan, R., Shah, Z., Vrinceanu, N. & Racheriu, M. Modeling the transmission phenomena of water-borne disease with non-singular and non-local kernel. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 26(11), 1294–1307 (2023).

Jan, R., Razak, N. N. A., Boulaaras, S., Rehman, Z. U. & Bahramand, S. Mathematical analysis of the transmission dynamics of viral infection with effective control policies via fractional derivative. Nonlinear Eng. 12(1), 20220342 (2023).

Alyobi, S. & Jan, R. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of fractional dynamics of infectious diseases with control measures. Fractal Fraction. 7(5), 400 (2023).

Alshehri, A., Shah, Z. & Jan, R. Mathematical study of the dynamics of lymphatic filariasis infection via fractional-calculus. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 138(3), 1–15 (2023).

Jan, R., Boulaaras, S., Alnegga, M. & Abdullah, F. A. Fractional-calculus analysis of the dynamics of typhoid fever with the effect of vaccination and carriers. Int. J. Numer. Model. Electronic Netw. Dev. Fields 37(2), e3184 (2024).

Al-Hdaibat, B., DarAssi, M. H., Ahmad, I., Khan, M. A. & Algethamie, R. Investigating tuberculosis dynamics under various control strategies: A comprehensive analysis using real statistical data. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 1, 1 (2025).

Al-Hdaibat, B. et al. Numerical investigation of an SIR fractional order delay epidemic model in the framework of Mittag-Leffler kernel. Nonlinear Dyn. 1, 1–21 (2025).

Al-Hdaibat, B., Khan, M. A., Ahmad, I., Alzahrani, E. & Akgul, A. Modeling and analyzing the dynamics of brucellosis disease with vaccination in the fractional derivative under real cases. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 1, 1–22 (2025).

Asma, M. Y. et al. A mathematical model of vaccinations using new fractional order derivative. Vaccines 10(12), 1980 (2022).

Alzahrani, E., El-Dessoky, M. M. & Khan, M. A. Mathematical model to understand the dynamics of cancer, prevention diagnosis and therapy. Mathematics 11(9), 1975 (2023).

Key Statistics for Breast Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/about/how-common-is-breastcancer.html.

Albeshan, S. M. & Alashban, Y. I. Incidence trends of breast cancer in Saudi Arabia: A joinpoint regression analysis (2004–2016). J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 33(7), 101578 (2021).

Ulam, S. M.Vol. 29 (New York, 1960).

Ulam, S. M. Problems in modern mathematics. Courier Corporation, 2004.

Filippov, A. F. Differential Equations with Discontinuous Righthand Sides (Springer, Dordrecht, 1988).

Cesari, L. Optimization Theory and Applications: Problems with Ordinary Differential Equations (Springer-Verlag, New York, 1983).

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number WE-44-0043.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SA: Formal analysis, supervision, review and editing, software implementation and editing. HA: Reviewed, supervision, formal analysis and editing, writing the original draft. SS: Conceptualization, formal analysis, review.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdelmohsen, S.A.M., Alyousef, H.A. & Saifullah, S. Fractional order breast cancer model with therapy, prevention diagnosis and optimal control based on real data. Sci Rep 15, 26369 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03357-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03357-1