Abstract

Spiking neural networks drawing inspiration from biological constraints of the brain promise an energy-efficient paradigm for artificial intelligence. However, challenges exist in identifying guiding principles to train these networks in a robust fashion. In addition, training becomes an even more difficult problem when incorporating biological constraints of excitatory and inhibitory connections. In this work, we identify several key factors, such as low initial firing rates and diverse inhibitory spiking patterns, that determine the overall ability to train in the context of spiking networks with various ratios of excitatory to inhibitory neurons. The results indicate networks with biologically-realistic excitatory:inhibitory ratios can reliably train at low activity levels and in noisy environments. Additionally, the Van Rossum distance, a measure of spike train synchrony, provides insight into the importance of inhibitory neurons to increase network robustness to noise. This work supports further biologically-informed large-scale networks and energy efficient hardware implementations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Current advances in artificial intelligence (AI) have led to increasingly power intensive training of large network models that is unsustainable in the long-term. These models are computed on farms of processor units and graphics cards, limited by inefficient data exchange between processing and memory storage1. Due to these constraints, new methodologies are needed to fundamentally change the paradigm and envision efficient computation. The brain provides significant inspiration, due to its ultra-efficient capabilities of performing a wide range of tasks in an adaptive and robust fashion. Spiking neural networks (SNNs) inspired by the spiking behavior of the brain could therefore provide an energy efficient paradigm in machine learning2,3. Moreover, neuromorphic implementations of these spiking neural networks could support novel hardware accelerators, although more research is needed to understand how to train and map such biologically-realistic networks effectively.

To further the understanding of training SNNs with progressively more biological realism, this work looks directly into the ratios of excitatory and inhibitory neurons and corresponding activity within a network being trained. In various regions of the mammalian brain, the ratio between excitatory and inhibitory neurons varies between approximately 10:90 to 90:10 with 80:20 being the approximate excitatory:inhibitory (E:I) ratio across the adult mouse brain as a whole4. Our work investigates networks within this range relevant to rodent brain regions5 and analyzes their spiking activity. Additionally, a variety of network initial conditions were trained on two AI-relevant datasets, namely the Fashion-MNIST (Modified National Institute of Standards and Technology) image dataset6 and Spiking Heidelberg Digits (SHD) audio dataset7. Overall, the analysis here provides a deeper look at the relationship between spiking behavior and network training performance. While previous work has relied on a mathematical derivation for optimal initialization, in this work we look for a more general activity-based solution that is potentially applicable beyond leaky-integrate-and-fire (LIF) models8. This solution provides some guidelines for increased training robustness and efficiency of relevance to spiking neural networks towards biologically realistic implementations.

Our work focuses on the utilization of the most fundamental SNN architecture (a feedforward network with a single hidden layer) and provides a key starting point towards large-scale biologically-realistic models by incorporating and analyzing excitatory and inhibitory activity. We lay initial steps in understanding the potential of utilizing artificial intelligence-based learning rules as a comparison point for future biologically-realistic training and the parallels that already exist in these two systems. Additionally, we take the analysis here and give potential implications for the current state-of-the-art models. Specifically, recent advancements in memristive neuromorphic hardware are promising for implementations of neural networks9 but come with two challenges (1) That network weights are bound based on the always positive conductance of the memristive devices and can be considered positive or negative weight by adding or subtracting the corresponding current through the device9,10. (2) Memristive devices have an inherent level of noise, during both reading and writing, which needs to be addressed when designing and analyzing algorithms11,12. In this work, we investigate potential applicability by requiring the weights to be either excitatory or inhibitory, which we address in our E:I ratio analysis with inherent noisy training.

This work aims to understand the importance and benefits of biologically-informed SNN design and analysis. To this end, the following key points summarize the contributions of this work:

-

Networks with sparser initial spiking activity, correlating to increased energy efficiency, successfully train more often than inefficient networks with higher initial firing rate.

-

Networks with biologically realistic E:I ratios, e.g. 80:20 , train to higher accuracy in noisy training environments across different datasets.

-

Analyzing SNNs with neuroscience-based metrics, e.g. the Van Rossum distance13, provides insight into how different populations of neurons are statistically different from one another across training.

-

In successfully trained, higher performing networks, and consistent with neurobiological evidence, inhibitory neurons display a greater diversity of spiking patterns than excitatory neurons, offering insight into how biologically-informed E:I ratios perform well in noisy environments.

Methods

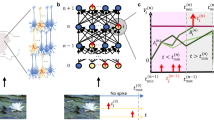

The goal of this work is to understand the interplay of excitatory and inhibitory activity in networks trained on AI tasks. To investigate this, we trained network architectures consisting of a spike generator input layer, a LIF neuron hidden layer with various E:I ratios, and a leaky-integrator output layer (Fig. 1a–b). The network architectures were feedforward networks since this architecture is the fundamental artificial neural network architecture. The size of the network was dependent on the dataset with the Fashion-MNIST dataset having sizes of 784-100-10 for the input-hidden-output layers. The SHD dataset training utilized networks of size 700-200-20. Each layer was fully connected to the following layer and initialized with normally distributed weights. Simulations used a 1 ms time steps and lasted for 100 ms for the Fashion-MNIST data and 200 ms for the SHD data and calculated using the forward Euler method (see Fig. 1). The following equations describe the synaptic current and LIF model used:

Where \(I_{syn}[t]\) is the synaptic current that decays with a \(\tau _{syn}\) = 5 ms. Each time step the current spikes, denoted with \(S_i[t]\) from each of the i neurons in the previous layer were multiplied by their connecting weight, \(W_i\), which generated an increase in synaptic current. The voltage of each hidden layer neuron, V[t], had an exponential decay with \(\tau _{mem}\) = 10 ms. Finally, if the voltage was greater than 1 mV, the neuron would fire and reset to 0 mV. A negative log-likelihood loss function was calculated at each time step and used with an exponential surrogate gradient function to calculate weight updates for training14.

Where the loss of a given network parameterization (\(l(\theta )\)) is determined to be a logarithmic relationship across n classes where the predicted value \(\hat{y_{\theta ,i}}\) is compared to the actual value \(y_i\).Simulations were repeated with a batch size of 256 for 30 epochs of training on the Fashion-MNIST dataset and 200 epochs of training on the SHD dataset to allow for direct comparison to the literature14. All hyperparameters are listed in Table 1.

Fashion-MNIST and SHD datasets were used with two different processes for generating spiking data. Fashion-MNIST is a typical small-scale benchmark in artificial neural networks and contains 60,000 grey-scale clothing images labeled for 10 different classes. Current state-of-the-art non-spiking multilayer perceptron’s (MLPs) achieve over 99% accuracy, but we note that non-spiking MLPs of a similar architecture (100 neuron hidden layer) achieve 87% accuracy6,15. To translate to a spiking domain, we utilize a latency encoding from the literature to translate each individual pixel (of the 28x28 pixels) to a single spike time based on the pixel intensity14. Higher intensity pixels correspond to a neuron firing at an earlier time, while lower intensity pixels correspond to later firing times (with an exponential translation function). Additionally, pixels with an intensity below the minimum threshold translate to a neuron that does not fire. In contrast, the SHD dataset utilizes a biologically realistic model of the inner ear to generate 700 spike trains (with an average of 7 spikes per neuron across the entire dataset)7. The 10,420 recordings represent 20 different classes corresponding to the spoken numbers “zero” through “nine” in English and German.

The hidden layer was constructed of excitatory and inhibitory neurons. Excitatory and inhibitory neurons were implemented with weights that were bounded after each update using a rectified linear unit function. This caused all weights that changed sign after an update to be set to 0, and all other weights left unaffected. Initialization of connections were randomized using the absolute value of a normal distribution for weights coming from an excitatory neuron, and the negative absolute value of a normal distribution for weights coming from an inhibitory neuron. The input layer consisted entirely of excitatory neurons to create activity in the subsequent layer of the network

To analyze the network activity, a range of input to hidden network connections was tested. The input to hidden connections were generated using the absolute value of a normal distribution using a range of standard deviations (changing the initial hidden layer firing rate). Each standard deviation was applied on four E:I ratios: 50:50, 80:20, 95:5 and 100:0 with eight repeat trials and trained on a spike-latency encoded Fashion-MNIST dataset using the surrogate gradient training algorithm6,14.

Furthermore, additional tests were conducted utilizing a dataset designed specifically for the spiking domain, the SHD dataset7. This dataset creates biologically-realistic spiking patterns by processing audio recordings through a cochlear model to create 700 spike trains for each individual audio recording. In total, there are 20 different classes corresponding to audio recordings of the numbers “zero” through “nine” in English and German (Supplemental Fig. S1). Again, a range of weight initializations was used to simulate a range of initial hidden layer firing rates. All simulation code and the corresponding analysis code is available at https://github.com/ADAM-Lab-GW/E-I-SNN.

Noisy training

Neuromorphic hardware, particularly based on emerging memristive devices, are known to have noisy weight updates11,12. While significant progress in algorithmic solutions has been made to support highly precise programmability16,17 these come at the cost of additional hardware overhead. Utilizing the most successful weight initialization from earlier trials, \(\sigma _{init}=0.001\), additional trials were performed with a noisy weight update. The noise levels investigated ranged from 1% to 100% of \(\sigma _{init}\) which mirrored the experimental range of noise within oxide-based resistive switches18. While other work has proposed randomizations to STDP methods19, we add noise to the backpropagation updates. At each batch weight update, a Gaussian noise was added to the ideal weight update (Fig. 2a). The noise level was determined by the standard deviation of the distribution. A range of noise levels were used to span a wide enough range to visualize progressive decline in accuracy across all networks. The noise levels are calculated as a ratio of the weight initialization from the input to hidden layer. Additionally, each parameter configuration was repeated 16 times. Each repetition used a different random seed to generate the initial weights, and the random noise generated for each update.

Network protocol overview and training results. (a) The spiking networks consist of three unique fully connected layers. The input layer consists of excitatory spike generators. The hidden layer consists of LIF neurons that have either excitatory or inhibitory weight connections to the output layer of leaky-integrators. (b) Sample Fashion-MNIST activity of the network starting with the input layer. Spikes of the hidden layer are indicated with a raster plot inset. Hidden layer activity is then propagated to the output where the highest voltage trace corresponds to the networks chosen class (drawn in black). (c) Network ability to train on the Fashion-MNIST dataset relative to their initial hidden layer firing rate. The different activity levels correspond to the different initial weight distributions. Every trial corresponds to an individual point on its respective graph. Training consisted of 4 different E:I ratios (left to right 50:50, 80:20, 95:5, 100:0). The black line at 86% accuracy shows the best single trial accuracy of previous training of a network of the same size and training but with unbounded weights14 (d) Network ability to train on the SHD dataset across a range of initial hidden layer firing rates. From left to right 4 E:I ratios: 50:50, 80:20, 95:5, 100:0. The black line at 48% accuracy represents a network of the same size but with unbounded weights.

Metrics and analysis

Neuroscience has produced a variety of metrics to analyze the spiking behavior of neurons at the population, pair, and individual level20,21. Taking inspiration from neuroscience, we analyzed our networks using a few metrics suggested in the neuroscience literature and applied them in this artificial intelligence training environment. These neuroscience methods are further broken into two categories, temporal and frequency-based analysis influenced by the temporal and frequency encoding of the datasets. Additionally, we included standard metrics from machine learning analysis to provide a wider analysis of the network behavior. See Table 2 for an overview of the metrics.

Temporal metrics

The temporal analysis of the network focused on the relative timing of the hidden layer neurons22,23. This was done by binning the number of spikes temporally across each simulation which corresponds to a single test case. Binning was done on a time step basis (1 ms). Across multiple simulations, we averaged the activity of the hidden layer across each training case. Activity was then compared across data classes and compared between excitatory and inhibitory neurons of the hidden layer.

To further analyze the relationship between neurons and their firing patterns we utilize the Van Rossum distance13. This calculation is a single metric to compare spike trains between any neuron pairs using the previously marked spike times. Previously, the metric was used as a basis for other training methods24, but we will use it here as a method of analysis of the network dynamics within the surrogate gradient training. The Van Rossum distance was calculated and averaged across the entire training data. Distance was calculated using an exponential decay kernel function, which mirrors the leaky-integrator output neurons and functions using the following equations.

In these equations, the spike train of neuron a is given by \(f_a(t)\) and is convolved with the exponential decay function to give \(g_a(t)\) using \(\tau _d\) = 1 ms. The distance is then the integral of the difference squared calculated as dist(a, b). Based on this, the Van Rossum distance provides a numerical distance between neurons that mirrors the error calculation used for the network training.

Frequency metrics

Frequency analysis methods focus on the inter-spike intervals (ISIs) of the networks22,25. ISIs measure the time difference between successive spikes from any given neuron. While temporally encoded Fashion-MNIST doesn’t provide ISIs within the input layer due to the single spike per neuron, the hidden layer does have the ability to produce multiple spikes from a single neuron. ISIs were measured by simulating each training case and collecting the list of all hidden layer neuron ISIs across the entire dataset. This can be subdivided based on ISIs from excitatory or inhibitory neurons and based on dataset class. From the list of ISIs we can create a distribution and compare distributions relative to network architectures and across training.

The inverse of the ISIs was also computed to find the firing frequency and analyzed over the network training23,26. Firing frequency provides the rate of firing at a given time throughout the simulation. Additionally, a similar metric of firing rate, which is averaged over a duration of time, can provide a higher level of analysis.

Training metrics

Finally, the network itself can be analyzed in terms of its ability to train, and the weight modifications needed for the network to train8. Weights are the only parameter being updated by the training rule, and thus are fundamental in analyzing how the network is training. Additionally, weight analysis can allow us to see what features the network is learning throughout training. To compare network abilities in the classification task, the accuracy and loss values were calculated throughout the training indicating the speed and peak abilities of the network with both datasets2. This metric allowed us to see the stability in network accuracy during the end of training, as well as the rate at which different networks reached their final accuracy.

Results

Network accuracy versus initial firing rate

Non-noisy networks using the range of initial conditions, i.e. weight distributions and random seeds, trained on Fashion-MNIST were able to train to over 80% accuracy, which is similar to networks of the same size with unbounded weights14 (Fig. 1c). Accuracy is shown as peak accuracy measured across the 30 epochs of training and we observed no overfitting in the trials we have measured. For networks with E:I ratios 80:20, 95:5, and 100:0, the best performing networks were initialized with weights distributions generating initial firing rates within the biologically-realistic bounds between 0.01 Hz and 25.6 Hz27, leading to an energy-efficient implementation28 while still retaining a high accuracy performance. Networks with a high percentage of inhibitory neurons, e.g. 50:50, were only able to train at the lowest end of the tested activity range, but the accuracy performance was not robust across the 8 repeat trials with different random seeds for the same distributions. In contrast, 100:0 networks exhibited high accuracy (over 80%) at initial firing rates over 50Hz. However, these upper activity levels would not be energy efficient due to unnecessarily high spiking activity levels, nor do they confer additional accuracy benefits. Therefore, we focused on the lower activity spectrum for further analysis.

The SHD accuracy results mirror a similar trend with respect to activity levels and accuracy (Fig. 1d). Lower activity levels correspond to higher accuracy across all E:I ratios. Accuracies reached 45%, which was comparable to the accuracy of the unbounded hidden layer for this network architecture7. An interesting result is that the purely excitatory network trained on SHD show poor accuracy, probably because of the intrinsic high level of input noise in this dataset. The networks with inhibitory neurons train to higher accuracy, which is an indication of the importance of proper ratios of excitatory:inhibitory activity in noisy environment. Compared to Fashion-MNIST the SHD has significantly less immediate separation between classes based on the input spike trains (which are noisier and higher activity). As an example, spike trains differ significantly between the pullover class and sandal class of the Fashion-MNIST dataset (where pullover cases have activity in pixels that are never activated by the sandal cases). Alternatively, SHD does not have this level of separation between classes, combined with the noise from the initial data, resulting in minimal to no immediately decipherable difference between classes. Taken together, networks with biologically-realistic E:I of 80:20 maximized accuracy on both datasets when initialized with low levels of activity.

E:I ratio versus robustness to noisy weight updates

To test the potential for mapping such excitatory:inhibitory networks to noisy hardware, noisy weight updates were implemented by adding a normal distribution of varying standard deviations at every weight update. Each update included a calculated gradient and random noise (defined by \(\sigma _{noise}\)) that were added as a percentage of the initial weight distribution (defined by \(\sigma _{init}\)), which was then bounded to the excitatory or inhibitory values (Fig. 2a). Emerging device technologies, such as oxide-based resistive switches, experience high levels of stochasticity in the weight updates particularly in the high resistance state, therefore we have modeled a broad range \(\sigma _{noise}\) from 0% to 100% of \(\sigma _{init}\)29. Experimental results18 support this range which corresponds to the experimental stochasticity of oxide-based resistive switches in the range of 1% to 100% of the initial resistive states \(10^3 \Omega\) to \(10^6 \Omega\). Training was conducted over a range of E:I ratios initialized with low activity and trained on the Fashion-MNIST dataset. As the noise level increased, the accuracy decreased linearly for higher E:I ratios. Comparing the accuracy across ratios, the lower ratios (e.g. 70:30) performed at higher than 100:0 accuracy until higher noise levels where accuracy dropped off to near random chance (10%) (Fig. 2b). For example, the 50:50 network performance dropped at \(\sigma _{noise}\) equal to 30% of \(\sigma _{init}\), (\(\sigma _{noise} =0.3 \sigma _{init}\)) while other networks performed at 60% accuracy.

To understand the appropriate level of inhibitory activity to train in a noisy weight environment, such as those in neuromorphic hardware, the 100:0, purely excitatory network, provides the baseline for this analysis. Unlike an unconstrained network, the 100:0 network and the remaining E:I ratios provide a separation between the excitatory, glutamatergic, and inhibitory, GABAergic, activity which allows for further potential comparisons to the biology30. This also serves as an insightful investigation for future hardware mapping in memristive neural networks. In a memristive neural network an individual device can physically only carry a positive conductance and has an inherent level of noise. The simplest and most direct translation to hardware is a purely excitatory (positive weight) network. This is in line with prior work done in the literature on nonnegative weight constraints31. We assessed average accuracies across E:I ratios at three different noise levels (Fig. 2c–e). At the lower noise range, \(\sigma _{noise} =0.2 \sigma _{init}\), networks performed near 70% accuracy (Fig. 2c). Comparing the 16 repeat trials with a t-test at each E:I ratio, the 75:25 network performed at a higher accuracy than the 100:0 network at \(\sigma _{noise} =0.2 \sigma _{init}\) (\(p < 0.01\)). As the noise level increased, the 80:20 and 90:10 networks were the highest performing networks (Fig. 2d–e). While previous noiseless Fashion-MNIST results observed the 100:0 network was robust over a larger range of initial activity, these results indicate a biologically realistic ratios of excitatory and inhibitory activity provided optimal performance in the presence of noise.

Accuracy of networks with noisy weight updates. (a) Weight updates where the pre-update distribution determined the gradient for the update. The gradient and noise distributions were then combined with the weight distribution (this example was an \(\sigma _{noise}=0.2\sigma _{init}\)) and bounded to get the post-update weight distribution. (b) Average accuracy of the final 10 of 30 epochs of training with 16 repeat trials for each E:I ratio and noise level combinations. The average across repeat trials is represented with corresponding lines. Each trial is represented with individual points. Average accuracy across trials compared to the 100:0 E:I with positive accuracy differences indicating an improvement over the 100:0 networks at three different \(\sigma _{noise}\) levels: (c) \(0.2\sigma _{init}\), (d) \(0.4\sigma _{init}\), and (e) \(0.6\sigma _{init}\). T-tests were performed to calculate the difference between each E:I ratio and the baseline 100:0 network with * indicating p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, and *** for p < 0.001.

Successful versus unsuccessful training

To further understand the network training, the excitatory vs. inhibitory spiking activity can be observed by epoch for all classes to observe any differences between successful and unsuccessful networks. Activity levels before, during, and after training were visualized for the Fashion-MNIST dataset (Fig. 3 and animated in Supplemental Fig. S4). Initial activity spans from less than one hidden layer spike per image on average to over 1000 spikes per image. The initial activity falls along the ratio of the initial networks, in this case 80%. After a single epoch of training, the separation between class accuracy in successful networks (overall accuracy over 50%) was visible across the activity levels (Fig. 3a transition from column 2 to column 3). In this transition, class accuracy sharply divided between high accuracy classes and multiple classes remaining near baseline (observed as points being either green or grey with few points between the two). This gives indication to the clustering of accuracies in Fig. 1c because of repeatedly having few classes training very well as opposed to many classes all training to a moderate level. Additionally, the networks that increased in accuracy have a wider range of percent excitatory activity.

By comparison, networks that failed to train remain close to their original ratios of excitatory and inhibitory activity (Fig. 3b). While some individual classes of a network increased in accuracy (with an increased percent of excitatory activity), other classes sustained low accuracy (with a decreased percent of excitatory activity). The networks that have high initial activity were unable to train regardless of the excitatory activity percentage. While the overall network accuracy remained low, there were a few classes that did train. These few classes follow the same trend of a reduction of activity and an increase in the percent of excitatory activity, similar to the first epoch for successful networks, but occuring later in the training sessions. While this may indicate that the high activity networks may require longer training to reach high accuracy, this likely is not the case given that nearly all classes of the unsuccessful training have an initial decrease in percent excitatory activity, which goes against the typical trend for class accuracy improvements. Overall, this provides further insight on why some networks successfully train on Fashion-MNIST while others do not. In addition, the best training occurs when the percent of excitatory activity increases from baseline, as seen in both the successful networks, and the few classes that trained in the failed networks.

Fashion-MNIST class accuracy relative to the amount of activity and percent of activity that is excitatory across training. Separation is observed between (a) high accuracy networks (>50% maximum overall accuracy) at lower activity levels, and (b) low accuracy networks at high activity levels. (First column) Accuracy convergence curves for all trials colored by E:I ratio. (Second to fifth column) The initial network, after a single epoch of training, after ten epochs of training, and after training is complete (thirty epochs). Each network is represented by 10 points (for the 10 classes of the dataset) and all networks tested from Fig. 1 with E:I ratio of 80:20. Arrows denote the trend of successfully trained classes which exhibit an initial increase in the percent excitatory activity, and then a decline for the remainder of training (indicated with green arrows). Conversely, classes that fail to train are observed to see an initial reduction in the percent excitatory activity (indicated with a grey arrow). Across the successful and unsuccessful networks, successfully trained classes tend toward a lower activity level and higher percent excitatory activity, which is not observed occurring in the unsuccessful networks.

Evolution of E:I activity during training

The interplay of excitatory and inhibitory activity across Fashion-MNIST training classes was further analyzed for three representative trials of low, moderate, and high initial activity, all of which can train to over 50% accuracy (Fig. 4). Although even higher initial activity trials exist, those do not successfully train (see Fig. 1 and 3 for the full activity range). In the low initial activity networks, the first epoch was categorized by a large increase in activity (Fig. 4a). Additionally, the increased activity was disproportionately increased toward excitation, shown in the increased percent of excitatory activity in the first epoch of training. The moderate initial activity trials also displayed initial increased excitation, even though the overall activity remained relatively constant (Fig. 4b). The remainder of training for the low and moderate activity had a continuous incremental increase in inhibitory activity while the excitatory activity remained constant or slowly declined.

This trend was also consistent among classes within the dataset. Due to the conversion process from pixels to the spiking domain, objects that took up larger portions of the 28x28 pixel space generated more network activity. This was observed with the pullover class (labeled 2) having generated over 10 times the hidden layer activity at the end of training compared to the sandal class (labeled 5). The ratio of excitatory and inhibitory activity of lower activity classes tended to be higher than that of higher activity classes.

The example high initial activity shows an initial reduction in the percent of excitatory activity (Fig. 4c). The accuracy also does not increase until near epoch 10, at which time the proportion of excitatory activity for some classes increases. In this case, the classes that increased in proportional activity were the lower activity sandal and sneaker classes, labeled classes 5 and 7, respectively. Progressively as the training continued, similar to the other initial conditions, the excitatory activity decreased, but so did the inhibitory activity.

These general trends for low, moderate, and high initial activity are consistent throughout different E:I ratios. It should be noted that for higher initial ratios, the initial boost in percentage of excitatory activity was not visible since the activity was already at a percentage higher than that seen in the increases observed in the 50:50 trials. Therefore, the 50:50 trials were included here, as the other trends seen in the other E:I ratios are also seen in the 50:50 example. Additional examples for the 80:20 and 95:5 ratios are provided in Supplemental Fig. S2 and S3. Overall, this analysis confers with the previous section that networks train toward a low activity level (approximately one spike per neuron Fig. 4) with an initial increase in the percent excitatory activity that then decreases across training. Here, only the successful networks are analyzed and compared to see trends of an individual network across training. Particularly, specific classes of the dataset train differently in terms of excitatory and inhibitory activity and should be noted for further use of the Fashion-MNIST dataset.

Representative activity of three 50:50 Fashion-MNIST trials. The examples cover (a) low initial activity, (b) moderate initial activity, and (c) higher initial activity. The average number of excitatory (first row) and inhibitory (second row) spikes per image denoting the number of spikes generated by the hidden layer on average given any input image in the Fashion-MNIST dataset. Each line represents a different class with the black line noting the average across all classes. The percentage of excitatory spikes across training (third row) indicates the initial increase in proportional excitatory activity, followed by a decrease for the remainder of training in the low and moderate initial activity conditions. The adjustment of activity from the network training perspective, derived from the weight distributions before (fourth row) and after (fifth row) training. The accuracy convergence curve of each individual trial is included as the inset of the post-training weights.

Distances between neuronal pairs

To further contrast successfully and unsuccessfully trained networks, the Van Rossum distance, a measure of dissimilarity between spike trains, was calculated between pairs of excitatory-excitatory (E-E), excitatory-inhibitory (E-I), and inhibitory-inhibitory (I-I) hidden layer neurons for the Fashion-MNIST and SHD datasets (Fig. 5). By taking the average distance between all pairs across the entire dataset, all trials can be analyzed to compare between the three pair categories. Initially, the distribution of distances was the same regardless of initial excitatory and inhibitory ratio or pair category. The post-training trials are again divided between successful and failed networks. Fashion-MNIST success was defined as peak accuracy being greater than 50%. SHD success was defined as the average accuracy of the last 25 epochs being greater than 30%.

For the Fashion-MNIST distance, successful networks have a lower range of distances compared to the failed networks, corresponding with the overall activity level of the networks since higher activity levels correspond to higher distances (Fig. 5a-c). Successful 80:20 networks had an E-E median distance of 0.890 while failed networks were significantly higher at 1.532 median E-E distance. Additionally, we observed that the categories of distances in successful 50:50 networks were significantly different (p = 0.0091 Kruskal-Wallis, Supplementary Table 1). Interestingly, increased E:I ratios of 80:20 and 95:5 displayed further disparity in distances between the three different categories for successful networks (p < 0.0001, Kruskal-Wallis, Supplemental Table T1). The median Van Rossum distance between E-E neuron pairs was less than that of the I-I neuron pairs for all E:I ratios , with the 50:50 network showing the greatest increase of 39.6% between E-E and I-I median distance. This indicates the activity of inhibitory neurons are further differentiated compared to the excitatory neurons. This parallels the variation in inhibitory neuron types within subregions like the hippocampus, which exhibit a range of subtypes and firing behaviors32,33.

The trend across pair categories within measurements from the SHD dataset remains the same as the Fashion-MNIST dataset with E-E distances being the lowest average distance (Fig. 5d-f). Additionally, the I-I distances have a higher median compared to the E-E pairs (see Supplemental Table T2 for the Kruskal-Wallis statistical analysis). This further indicates the importance of differentiation of inhibitory neural activity in successful networks. In contrast, the range of distances of successful networks after being trained was higher than the initial range of distances, showing a greater increase in distances between initial and final networks on the SHD dataset. Furthermore, the range of distances from successful SHD dataset training were above 1.5, while Fashion-MNIST distances ranged below 1.5, indicating increased complexity of the SHD dataset and the increased need for differentiation of neurons to classify more complex data.

Average Van Rossum distances between hidden layer neuron pairs trained on the Fashion-MNIST (a–c) and SHD (d–f) datasets. Rows correspond to different E:I ratios 50:50 (a,d), 80:20 (b,e), 95:5 (c,f). The average distances between neuron pairs: excitatory-excitatory (E-E), excitatory-inhibitory (E-I), and the inhibitory-inhibitory (I-I) pairs. The distance is averaged across all cases. Each network tested in Fig. 1 is represented by a single average value for each of the three categories and make the distributions in each subfigure. The initial networks spread a range of distances based on their varied weight initializations but show equal distributions across the three categories. The successfully trained networks from the Fashion-MNIST trials are defined as networks with peak overall accuracy >50%, and have a lower distribution of distances, while the networks that fail to reach 50% accuracy are typically in a higher range of activity, with the difference between failure and success being stronger in higher E:I ratios. Successfully trained networks from the SHD trials are defined as networks with average accuracy >30% for the last 25 epochs. Using the Kruskal-Wallis test, the three categories are calculated to be statistically significantly different with p-values <0.0001 for the successful 80:20 and 95:5 networks, with I-I distances being the largest, and E-E distances being the lowest with * indicating p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, and *** for p < 0.001.

Discussion

Overall, our results demonstrate that within a mixed-sign constrained network a biologically realistic range of E:I ratios between 80:20 and 95:5 in the hidden layer works best for hardware-aware applications with energy efficient activity as well as being robust in noisy environments. In all four E:I ratios, we observed trials successfully training to >80% accuracy on the Fashion-MNIST dataset, and >40% accuracy on the SHD dataset. Both results are near the benchmark accuracy level of an equivalent network with unbounded weights. We observed that the accuracy of networks at low activity is similar across E:I ratios for the Fashion-MNIST image dataset, but the inclusion of inhibitory neurons in our networks provide significant accuracy benefits on the noisy SHD audio dataset. Additionally, the inclusion of noise within weights in the Fashion-MNIST training finds that the inclusion of inhibitory neurons is important for network robustness. Future work will investigate the potential of transmodal training for these networks using audio-visual datasets.

Our results also indicate that as network activity increases, the overall peak performance of the network decreases, eventually leading to 10% accuracy (the baseline accuracy of the Fashion-MNIST dataset). Based on this data, we hypothesize that the increased initial activity was too high to provide any substantial differentiation between classes, and thus reduces the ability for the network to train. When the minimal spiking activity occurs, we hypothesize the activity is at an optimal point of differentiability and trains to a higher degree of accuracy. This trend remains across all E:I ratios, though the rate at which accuracy decreases as activity increases varies across E:I ratios. Additional analysis with statistical methods such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) may provide a deeper understanding into the level of separation occurring at the hidden layer for each class34,35,36.

To determine the E:I ratio optimal for potential translation to a neuromorphic hardware implementation, we utilized a noisy environment with comparable noise levels in the weight updates to compare the networks in the low activity range. From these trials, we see that networks within the biologically realistic E:I ratios (80:20 to 95:5) allow for the best performance in terms of accuracy within the noisy environment with \(\sigma _{noise}\) between 20% to 60% of the \(\sigma _{init}\). This indicates that the biologically realistic range of E:I ratios also provides the most benefits in combination with the biologically realistic firing range in hardware realizations.

On a macroscopic level, lower activity while being the most energy efficient is optimal for maximizing accuracy. The three representative activity levels see the trends toward a central activity level (approximately 50-100 hidden layer spikes). This appears counterintuitive given that the propagation of spikes should be indicative of the propagation of information, thus more activity should be better. These results oppose this presupposition, and we hypothesize that the lower levels of activity provide a starting point with greater pattern separation between classes than a high activity network. Based on Fig. 3b, high activity networks lack the initial increase in percent excitatory activity which typically corresponded to an increase in accuracy in the successful networks. Instead, these high activity networks mainly trend toward and increase in inhibitory activity . As an example, this would correspond with the network needing excitatory activity to create a general picture of each class, and then the progressive increase in excitatory activity helps specify that image (which follows the continuous increase in inhibitory activity after excitatory activity flattens, Fig 4 row 1, 2, and 3). This is reflected in the Van Rossum distances with successful networks having a low E-E distance, indicating the similarity between the spike trains of excitatory neurons (Fig. 5).

Conversely, the inhibitory neurons had the greatest average distance between pairs, noting their differentiation of activity. In terms of pattern recognition and pattern separation, the higher distance corresponds to inhibitory neurons providing a significantly higher separation compared to the excitatory neurons. This result is in line with experimental results from neuroscience, where biological networks are known to have greater physiological diversity across interneurons. Inhibitory interneurons exhibit differentiation in their connectivity37, spiking behavior33, and down to the genetics of each interneuron type38. In our network after training, even though the LIF models themselves are identical, the weights of the network support an emergent diversity in inhibitory activity. Additionally, the LIF models were connected with exponential decay functions for synaptic transmission. Together this lacks deep biological realism that many other models provide39, and thus the exact conclusions of this work may not perfectly map to those contexts. However, our focus on spiking activity allows for the conclusions here to be tested and adjusted accordingly on future work that incorporates biologically-realistic neuronal models. These would likely provide even more spiking diversity across training furthering the need for biologically-informed E:I ratios and an understanding of the impact of E:I ratios on network training capability. To this end, additional comparisons to the unconstrained network, such as training in noisy weight update environments, may provide further insight into the importance of biologically-informed E:I ratios.

Previously, other work has expressed methods for network initialization using a mathematical approach8. Our work separates from the traditional mathematics of artificial SNNs in favor of an analysis utilizing metrics from neuroscience. This biologically-inspired approach could also more readily provide insight into other networks beyond the LIF models, and potentially towards more complex models40,41,42. It should also be noted that this work separates from the traditional neuroscience, where prior works have focused the stability of large biologically-realistic models in terms of spiking activity43,44, ours focuses on the actual use of network variants in AI-relevant classification tasks. From the AI perspective, previous work has sought to simplify the initialization of large-scale artificial neural networks45. Additionally, we note that the learning rule, surrogate gradient error backpropagation through time, lacks direct biological realism46. This learning rule does provide an effective solution for network tuning and provides a comparison point between artificial intelligence training and future work with biologically realistic learning rules. While the LIF models used in this work provide a basis for future analysis, other models such as the Izhikevich, Morris-Lecar, Hodgkin-Huxley, among many others, may provide greater insight to underlying biological parallels47,48,49. Additionally, analysis of metrics noted but not included here, such as comparing inter-spike intervals, firing frequency, and weight analysis of the underlying trained patterns, could provide additional insight for hardware-aware training and network architectures. Overall, we find key guiding principles, such as biologically-informed E:I ratios, that can be applicable to SNNs. In these comparisons, our work seeks to bridge the gap between artificial intelligence and neuroscience.

Conclusion

In this work, we investigated the network conditions conducive to successful training via surrogate gradient backpropagation. Our results demonstrate that the minimal spiking activity produces networks that train successfully. We also observe that the optimal ratios of stability in noisy datasets and noisy training environments are best met in a biologically realistic E:I ratio, thus indicating that both excitatory and inhibitory activity would likely be required for successful neuromorphic hardware based on imperfect devices. Potentially, large biologically realistic networks can be initialized based on this minimal activity principle and biologically-informed parameters to avoid an exhaustive and computationally expensive parameter search.Furthermore, these results allows for future work to continue towards biological realism with modified detailed neuron models and data-driven structural diversity32,39 as well as providing insight for hardware implementations.

Data availability

Code used for the simulation and analysis is available at https://github.com/ADAM-Lab-GW/E-I-SNN

References

Efnusheva, D., Cholakoska, A. & Tentov, A. A survey of different approaches for overcoming the processor-memory bottleneck. Int. J. Inform. Technol. Comput. Sci. 9, 151–163. https://doi.org/10.5121/ijcsit.2017.9214 (2017).

Pfeiffer, M. & Pfeil, T. Deep Learning With Spiking Neurons: Opportunities and Challenges. Frontiers in Neuroscience12 (2018).

The new NeuroAI. Nature Machine Intel. 6, 245–245. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-024-00826-6 (2024).

Rodarie, D. et al. A method to estimate the cellular composition of the mouse brain from heterogeneous datasets. PLoS Comput. Biol. 18, e1010739. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010739 (2022).

Alreja, A., Nemenman, I. & Rozell, C. J. Constrained brain volume in an efficient coding model explains the fraction of excitatory and inhibitory neurons in sensory cortices. PLoS Comput. Biol. 18, e1009642. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009642 (2022).

Xiao, H., Rasul, K. & Vollgraf, R. Fashion-MNIST: A Novel Image Dataset for Benchmarking Machine Learning Algorithms, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1708.07747 (2017). arXiv:1708.07747.

Cramer, B., Stradmann, Y., Schemmel, J. & Zenke, F. The Heidelberg spiking data sets for the systematic evaluation of spiking neural networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learning Syst. 33, 2744–2757. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2020.3044364 (2022).

Rossbroich, J., Gygax, J. & Zenke, F. Fluctuation-driven initialization for spiking neural network training. Neuromorphic Comput. Eng. 2, 044016. https://doi.org/10.1088/2634-4386/ac97bb (2022).

Yousuf, O. et al. Layer ensemble averaging for fault tolerance in memristive neural networks. Nat. Commun. 16, 1250. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56319-6 (2025).

Wan, W. et al. A Voltage-Mode Sensing Scheme with Differential-Row Weight Mapping for Energy-Efficient RRAM-Based In-Memory Computing. In 2020 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology, 1–2, https://doi.org/10.1109/VLSITechnology18217.2020.9265066 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Resistive switching materials for information processing. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 173–195. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-019-0159-3 (2020).

Adam, G. C., Khiat, A. & Prodromakis, T. Challenges hindering memristive neuromorphic hardware from going mainstream. Nat. Commun. 9, 5267. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07565-4 (2018).

van Rossum, M. C. W. A Novel Spike Distance. Neural Comput. 13, 751–763. https://doi.org/10.1162/089976601300014321 (2001).

Neftci, E. O., Mostafa, H. & Zenke, F. Surrogate gradient learning in spiking neural networks: Bringing the power of gradient-based optimization to spiking neural networks. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 36, 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2019.2931595 (2019).

Mukhamediev, R. I. State-of-the-art results with the fashion-MNIST dataset. Mathematics 12, 3174. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12203174 (2024).

Song, W. et al. Programming memristor arrays with arbitrarily high precision for analog computing. Science 383, 903–910. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adi9405 (2024).

Alibart, F., Gao, L., Hoskins, B. D. & Strukov, D. B. High precision tuning of state for memristive devices by adaptable variation-tolerant algorithm. Nanotechnology 23, 075201. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/23/7/075201 (2012).

Garbin, D. A Variability Study of PCM and OxRAM Technologies for Use as Synapses in Neuromorphic Systems. Ph.D. thesis, Université Grenoble Alpes (2015).

Wang, R., Thakur, C. S., Hamilton, T. J., Tapson, J. & Van Schaik, A. A stochastic approach to STDP. In 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), 2082–2085, https://doi.org/10.1109/ISCAS.2016.7538989 (IEEE, Montréal, QC, Canada, 2016).

Kass, R. E., Eden, U. T. & Brown, E. N. Analysis of Neural Data. Springer Series in Statistics (2014), 1 edn.

Gerstner, W., Kistler, W. M., Naud, R. & Paninski, L. Neuronal Dynamics: From Single Neurons to Networks and Models of Cognition (University Press, Cambridge, 2014).

Cariani, P. Temporal coding of periodicity pitch in the auditory system: An overview. Neural Plast. 6, 147–172. https://doi.org/10.1155/NP.1999.147 (1999).

Cariani, P. Temporal codes and computations for sensory representation and scene analysis. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 15, 1100–1111. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNN.2004.833305 (2004).

Zenke, F. & Ganguli, S. SuperSpike: supervised learning in multilayer spiking neural networks. Neural Comput. 30, 1514–1541. https://doi.org/10.1162/neco_a_01086 (2018).

Kreuz, T., Haas, J. S., Morelli, A., Abarbanel, H. D. I. & Politi, A. Measuring spike train synchrony. J. Neurosci. Methods 165, 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.05.031 (2007).

Dayan, P. & Abbott, L. F. Theoretical neuroscience: Computational and mathematical modeling of neural systems (Computational Neuroscience (Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, Cambridge, Mass, 2001).

Sanchez-Aguilera, A. et al. An update to Hippocampome.org by integrating single-cell phenotypes with circuit function in vivo. PLoS Biol. 19, e3001213. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001213 (2021).

Harris, J. J., Jolivet, R. & Attwell, D. Synaptic Energy Use and Supply. Neuron 75, 762–777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.019 (2012).

Grossi, A. et al. Fundamental variability limits of filament-based RRAM. In 2016 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), 4.7.1–4.7.4, https://doi.org/10.1109/IEDM.2016.7838348 (IEEE, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016).

Chapman, C. A., Nuwer, J. L. & Jacob, T. C. The Yin and Yang of GABAergic and glutamatergic synaptic plasticity: Opposites in balance by crosstalking mechanisms. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 14, 911020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsyn.2022.911020 (2022).

Chorowski, J. & Zurada, J. M. Learning understandable neural networks with nonnegative weight constraints. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learning Syst. 26, 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2014.2310059 (2015).

Wheeler, D. W. et al. Hippocampome.org 2.0 is a knowledge base enabling data-driven spiking neural network simulations of rodent hippocampal circuits. eLife12, RP90597, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.90597 (2024).

Komendantov, A. O. et al. Quantitative firing pattern phenotyping of hippocampal neuron types. Sci. Rep. 9, 17915. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52611-w (2019).

Kobak, D. et al. Demixed principal component analysis of neural population data. eLife5, e10989, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.10989 (2016).

McInnes, L., Healy, J., Saul, N. & Großberger, L. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection. Journal of Open Source Software3, 861, https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00861 (2018).

Lazarevich, I., Prokin, I., Gutkin, B. & Kazantsev, V. Spikebench: An open benchmark for spike train time-series classification. PLoS Comput. Biol. 19, e1010792. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1010792 (2023).

Fishell, G. & Kepecs, A. Interneuron types as attractors and controllers. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 43, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-neuro-070918-050421 (2020).

Wamsley, B. & Fishell, G. Genetic and activity-dependent mechanisms underlying interneuron diversity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2017.30 (2017).

Kopsick, J. D. et al. Robust resting-state dynamics in a large-scale spiking neural network model of area CA3 in the mouse hippocampus. Cogn. Comput. 15, 1190–1210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12559-021-09954-2 (2023).

Izhikevich, E. M. Dynamical Systems in Neuroscience: The Geometry of Excitability and Bursting (Computational Neuroscience (MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass, 2007).

Venkadesh, S., Komendantov, A. O., Wheeler, D. W., Hamilton, D. J. & Ascoli, G. A. Simple models of quantitative firing phenotypes in hippocampal neurons: Comprehensive coverage of intrinsic diversity. PLoS Comput. Biol. 15, e1007462. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007462 (2019).

Teeter, C. et al. Generalized leaky integrate-and-fire models classify multiple neuron types. Nat. Commun. 9, 709. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02717-4 (2018).

Gast, R., Solla, S. A. & Kennedy, A. Neural heterogeneity controls computations in spiking neural networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2311885121. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2311885121 (2024).

Denève, S. & Machens, C. K. Efficient codes and balanced networks. Nat. Neurosci. 19, 375–382. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4243 (2016).

Ding, N. et al. Parameter-efficient fine-tuning of large-scale pre-trained language models. Nature Machine Intell. 5, 220–235. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-023-00626-4 (2023).

Lillicrap, T. P., Santoro, A., Marris, L., Akerman, C. J. & Hinton, G. Backpropagation and the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 21, 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-020-0277-3 (2020).

Izhikevich, E. M. Dynamical Systems in Neuroscience (MIT Press, 2007).

Morris, C. & Lecar, H. Voltage oscillations in the barnacle giant muscle fiber. Biophys. J . 35, 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84782-0 (1981).

Hodgkin, A. L. & Huxley, A. F. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J. Physiol. 117, 500–544 (1952).

Wu, G., Liang, D., Luan, S. & Wang, J. Training Spiking Neural Networks for Reinforcement Learning Tasks With Temporal Coding Method. Frontiers in Neuroscience16, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.877701 (2022).

Bittar, A. & Garner, P. N. A surrogate gradient spiking baseline for speech command recognition. Front. Neurosci.16, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.865897 (2022).

Yin, B., Corradi, F. & Bohté, S. M. Accurate and efficient time-domain classification with adaptive spiking recurrent neural networks. Nature Mach. Intel. 3, 905–913. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-021-00397-w (2021).

Narkhede, M. V., Bartakke, P. P. & Sutaone, M. S. A review on weight initialization strategies for neural networks. Artif. Intell. Rev. 55, 291–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-021-10033-z (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the use of high-performance computing clusters, advanced support from the research technology services, and IT support at The George Washington University.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Energy Office of Science, CRCNS collaborative effort under grant numbers DE-SC00023000 (GWU) and DE-SC0022998 (GMU).

Additional support was provided by the National Institute of Health under grant number R01NS39600 and Air Force Office of Scientific Research under grant number FA9550-23-1-0173.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JAK and GCA conceived the experiments, JAK conducted the simulations, JAK generated initial analysis, JDK, GAA, and GCA provided additional analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors do not have any competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information 5.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kilgore, J.A., Kopsick, J.D., Ascoli, G.A. et al. Biologically-informed excitatory and inhibitory ratio for robust spiking neural network training. Sci Rep 15, 24798 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03408-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03408-7