Abstract

Leishmaniasis remains a significant public health challenge in southern Iran, particularly in the Fars province, where Shiraz is a major focus of the disease. This study aimed to elucidate the phylogenetic relationships of Leishmania species isolated from humans, sand flies, and reservoir hosts in Shiraz and its suburbs. Cutaneous slit biopsies were collected from 350 suspected human cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), and samples were also obtained from rodents (Tatera indica) and sand flies (Phlebotomus papatasi). Parasites were cultured, and DNA was extracted for PCR amplification of the minicircle kinetoplast DNA (kDNA) gene. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using Neighbor-Joining and Maximum Likelihood methods. The results revealed the presence of Leishmania major, L. tropica, and L. infantum, with L. major being the predominant species. Phylogenetic trees demonstrated high genetic similarity between local isolates and those from other regions, including Iran, the UK, and Spain. This study highlights the complex transmission dynamics of Leishmania in Shiraz and underscores the need for targeted control strategies. The findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the genetic diversity and evolutionary relationships of Leishmania species in endemic regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leishmaniasis, a vector-borne disease caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania, remains a major global public health challenge, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 700,000 to 1 million new cases occur annually (of which, an estimated 50 000 to 90 000 new cases of VL, with only 25–45% reported to WHO, and the rests relate to Cutaneous and mucocutaneous form), with over 350 million people at risk of infection worldwide1. The disease manifests in three primary forms: cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL), and visceral leishmaniasis (VL), each associated with significant morbidity and mortality. CL, characterized by disfiguring skin lesions, is the most prevalent form, accounting for approximately 95% of global cases2. While not fatal, CL imposes a heavy socio-economic burden due to prolonged treatment, stigma, and reduced quality of life, particularly in endemic regions with limited healthcare resources3.

The Middle East is a hotspot for leishmaniasis, with Iran ranking among the most affected countries. The Fars province in southern Iran, particularly its capital Shiraz, has emerged as a critical focus of CL, driven by ecological, climatic, and anthropogenic factors4. The region’s semi-arid climate, coupled with urbanization and agricultural expansion, creates ideal habitats for phlebotomine sand flies (genus Phlebotomus and Lutzomyia), the primary vectors of Leishmania5. Two Leishmania species dominate transmission in Iran: L. major (zoonotic CL, ZCL) and L. tropica (anthroponotic CL, ACL). ZCL is maintained in a sylvatic cycle involving rodent reservoirs (e.g., Tatera indica and Meriones libycus), while ACL circulates predominantly among humans, complicating control efforts6. Recent reports also highlight sporadic cases of L. infantum, typically associated with VL in the Mediterranean basin, further underscoring the dynamic epidemiology of leishmaniasis in Iran7.

The genetic diversity of Leishmania parasites plays a pivotal role in shaping disease presentation, transmission dynamics, and response to treatment. For instance, polymorphisms in kinetoplast DNA (kDNA) and other genetic markers have been linked to variations in virulence, drug resistance, and host specificity8.

Phylogenetic studies are thus critical for elucidating the evolutionary relationships between Leishmania strains, tracing their geographical origins, and identifying emerging hybrids or imported species that may alter local transmission patterns9. In Iran, molecular studies have primarily focused on human isolates, with limited data on parasites from vectors and reservoir hosts. This gap hinders a comprehensive understanding of the zoonotic and anthroponotic cycles that sustain Leishmania transmission in endemic regions like Shiraz10.

In Iran, L. major has identified as the predominant species in rural areas, often linked to rodent burrows near agricultural settlements, while L. tropica is more common in urban settings11. However, recent climate change, population displacement, and land-use alterations have blurred these ecological boundaries, leading to overlapping transmission cycles and atypical clinical presentations12,13. For example, a study in Isfahan reported hybrid Leishmania strains with genetic material from both L. major and L. tropica, raising concerns about adaptive evolution and potential challenges in diagnosis and treatment14. Such findings emphasize the need for continuous molecular surveillance to monitor genetic shifts and their public health implications.

In Shiraz, the rise of CL cases over the past decade has been attributed to rapid urbanization, which brings humans into closer contact with sand fly habitats and reservoir hosts. Despite ongoing control measures—including insecticide spraying, rodent control, and public health campaigns—the incidence of CL remains high, suggesting gaps in current strategies15. A critical limitation has been the lack of integrated data on the genetic relatedness of Leishmania isolates from humans, vectors, and animal reservoirs. Understanding these relationships is essential for identifying transmission hotspots, evaluating the role of non-human hosts in spillover events, and designing targeted interventions.

This study aimed to address these gaps by conducting a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of Leishmania species isolated from humans, sand flies (Phlebotomus papatasi), and rodents (Tatera indica) in Shiraz and its suburbs. Using minicircle kDNA sequencing, we compared local isolates with global strains to explore their genetic diversity, evolutionary origins, and potential linkages to regional and international transmission networks. Additionally, we assessed the zoonotic and anthroponotic contributions to CL epidemiology in Shiraz, providing insights into the mechanisms sustaining Leishmania persistence in this endemic focus.

Materials and methods

Study area

Fars province, located in southern Iran, covers an area of 122,400 square kilometers and includes 23 cities. Shiraz, the provincial capital, is situated at 29° 59′ 18″ North, 52° 58′ 37″ East, with an elevation of 1200–1500 m above sea level. The region has recently been identified as a significant focus of leishmaniasis, with increasing cases reported in both urban and rural areas.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with international, national, and institutional ethical guidelines. We declare that all experiments were performed in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0 and that all experimental protocols were approved by Ethical approval obtained from the Science and Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences on August 20, 2016 (Approved ID: IR.SUMS.REC. 1395.S475).

Sample collection

Cutaneous slit biopsies were collected from suspected human cases of CL in Shiraz and its suburbs from March 2018 to March 2020. Furthermore, Rodent samples were collected from captured Tatera indica. They were euthanized by deep anesthesia and impression smears and culture sampling were prepared from biopsies of their ears, spleen, feet, nose, and liver. Moreover, sand flies (Phlebotomus papatasi) captured by “Aspirating Tube Live Traps” in areas adjacent to hospitals, as well as through active field surveys conducted in Shiraz and its suburbs (Fig. 1). Rodents and sand flies were characterized by scientific taxonomic keys. Then, these samples were subsequently processed for parasite culture and molecular analysis.

Map of studied areas of Shiraz and its suburbs, southern Iran: Sangesiah (1), Soltanabad (2), Zafarabad (3), and Mahmoodabad (4), Kheirabad (5), Abshoor (6), Koohgari (7), Helalabad (8), Korbal (9), and Moezabad (10). Note This GIS map was generated and modified using “ArcMap 10.8” software by authors.

Human ethic notes

Consent to Participate: All subjects gave informed consent for inclusion before participating in the study. “Informed consent” was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardians.

Animal ethic notes

All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Science and Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences.

Parasite culture

Biopsies were transferred to the liquid phase of NNN medium (containing horse blood agar base and Locke’s solution) under sterile conditions and incubated at 24 ± 2 °C. For mass cultivation, cultures were transferred to RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Germany) supplemented with 10% inactivated fetal calf serum (Sigma), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Fig. 2).

Culture of Leishmania isolated from human, sand flies, and rodent hosts; A: Study on cultured Leishmania specimens under invert microscope, B: Preparation of modified NNN media for Leishmania culture in sterile condition, C: culture media prepared from rodents’ organs caught from Shiraz and its suburbs, D: transferring the biopsies of rodent rodents’ organs to the NNN culture medium tubes.

DNA extraction and PCR assays

DNA was extracted from glass slides and culture sediments using a kDNA extraction kit. PCR amplification of the minicircle kDNA gene was performed using specific primers (LINR4 and LIN17). The PCR products were visualized on 1.2% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. Reference strains of L. major (MHOM/IR/54/LV39), L. infantum (MHOM/DZ/82/LIPA59), and L. tropica (MHOM/SU/71/K27) were used for comparison.

PCR products obtained from Leishmania isolates collected from rodents, sand flies, and human clinical cases suspected of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) were purified using the QIAquick® Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). The protocol was performed as follows:

Each PCR product (20 μL) was combined with 5 μL of loading dye and electrophoresed on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with GelRed® (Biotium). DNA bands were visualized under UV light, and fragments of the expected size were excised from the gel using a sterile scalpel in a UV-equipped darkroom. The excised gel slices were transferred to sterile 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes. To dissolve the agarose, 750 μL of sodium iodide solution was added to each tube, followed by incubation at 65 °C for 10 min. The dissolved gel mixtures were then loaded onto QIAquick spin columns and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 1 min. The flow-through was discarded, and the columns were washed twice with 750 μL and 350 μL of Wash Buffer, respectively, with centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 1 min after each wash. Columns were transferred to fresh collection tubes prior to the second wash.

For DNA elution, 50 μL of molecular-grade distilled water was applied directly to the center of the column membrane. After a final centrifugation step (14,000 rpm, 1 min), the eluates containing purified DNA were collected in sterile 1.5 mL microtubes and stored for downstream applications.

Phylogenetic analysis

Finally, five sequences were aligned and analyzed using MUSCLE and BLAST in the GenBank database. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) and Maximum Likelihood (ML) methods in MEGA-7. Bootstrap values were calculated based on 1,000 replicates to assess the reliability of the trees.

Results

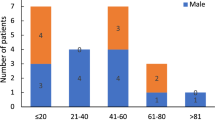

Among 354 suspected cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) cases analyzed via microscopy, culture, and/or PCR, 282 (79.7%) tested positive for Leishmania species based on minicircle kDNA gene amplification. Species-specific PCR identified L. major in 242 (85.8%), L. tropica in 38 (13.5%), and L. infantum in 2 (0.7%) of the confirmed cases.

A total of 135 rodents representing five species—Tatera indica (n = 92, 68.1%), Rattus rattus (n = 18, 13.3%), Meriones libycus (n = 13, 9.6%), Mus musculus (n = 10, 7.4%), and R. norvegicus (n = 2, 1.5%)—were captured alive across the study regions. PCR screening revealed 49.6% (67/135) positivity for Leishmania infection. Of these, 63.0% (58/92) of T. indica specimens tested positive, with 60.9% (56/92) specifically infected with L. major.

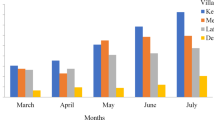

Sand fly collections yielded 7125 specimens, of which 5,380 (75.5%) belonged to the genus Phlebotomus. Species composition included P. papatasi (3,352; 47.0% of total catch), P. sergenti (1,134; 15.9%), P. alexandri (698; 9.8%), P. bergeroti (165; 2.3%), P. ansarii (18; 0.3%), P. major (8; 0.1%), P. mongolensis (3; 0.04%), and P. longiductus (2; 0.03%).

The detection of Leishmania infantum DNA was reported in two human clinical samples collected from suspected cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) cases. These samples were analyzed using microscopy, culture, and/or PCR methods, with PCR confirming the presence of L. infantum through species-specific amplification of the minicircle kDNA gene.

Note: While L. infantum is more commonly associated with visceral leishmaniasis (VL), its detection in cutaneous lesions in this study highlights its potential role in atypical presentations or overlapping transmission cycles in the region. The remaining Leishmania species (L. major and L. tropica) were detected in both human cases and reservoir hosts (rodents/sand flies), but L. infantum was only identified in human clinical samples here.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

Sequences of Leishmania isolates from three human cases, one T. indica rodent (1/92), and one P. papatasi sand fly (1/3352) were aligned with GenBank reference strains. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that three L. major isolates exhibited 100% similarity to Iranian strains (AB678349, KM555292) and 99–100% similarity to a UK-derived L. major strain (AF308685) (Fig. 3).

Sequences of L. major, isolated from Shiraz and Kharameh, which were aligned and compared with L. major sequences existing in GenBank; L. major 1 isolated from a patient (Accession no. MN179620), L. major 2 isolated from T. indica (Accession no. MN179621), and L. major 3 isolated from P. papatasi (Accession no. MN179622).

L. tropica isolates were closely related to Iranian (AB678350, KM491168) and UK (AF308689) strains (Fig. 4).

L. infantum isolates were most similar to strains from Spain (EU437407) and Iran (AB678348) (Fig. 5).

Phylogenetic trees

The NJ and ML phylogenetic trees revealed distinct clades for L. major, L. tropica, and L. infantum. The L. major isolates from humans, rodents, and sand flies clustered together, indicating a shared genetic lineage. Similarly, L. tropica and L. infantum isolates formed separate clades, reflecting their genetic distinctness (Figs. 6 and 7).

Consensus Phylogenetic Tree; phylogenetic relationship among various Leishmania species to each other as inferred by Neighbor-Joining tree based on minicircle kDNA gene. Numbers on branches are percentage bootstrap values of 1,000 replicates. The evolutionary distances between sequences were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood model and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The scale bar indicates an evolutionary distance of 0.2 nucleotides per position in the sequence. The reference sequences accession numbers are inserted. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA-7.

Consensus Phylogenetic Tree; Phylogenetic relationship among various Leishmania species to each other as inferred by Maximum Likelihood tree based on minicircle kDNA gene. Numbers on branches are percentage bootstrap values of 1000 replicates. The evolutionary distances between sequences were computed using the Kimura 2-parameter model and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The scale bar indicates an evolutionary distance of 0.2 nucleotides per position in the sequence. The reference sequences accession numbers are inserted. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA-7.

Discussion

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships of Leishmania species circulating in Shiraz, southern Iran, a region recognized as a major focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). Our results confirm the presence of three Leishmania species—L. major, L. tropica, and L. infantum—with L. major being the predominant species isolated from humans, rodents, and sand flies. The phylogenetic analysis revealed high genetic similarity between local isolates and strains from other regions, including Iran, the UK, and Spain, suggesting widespread transmission and potential introductions from neighboring areas. These findings have important implications for understanding the epidemiology of leishmaniasis in southern Iran and designing targeted control strategies.

In genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships, the phylogenetic trees constructed in this study demonstrated distinct clades for L. major, L. tropica, and L. infantum, consistent with previous reports from Iran and other endemic regions8,9. The L. major isolates from humans, rodents (Tatera indica), and sand flies (Phlebotomus papatasi) clustered together, indicating a shared genetic lineage and supporting the zoonotic nature of CL in Shiraz. This finding aligns with earlier studies that identified L. major as the primary causative agent of zoonotic CL (ZCL) in rural and peri-urban areas of Iran, where rodents serve as reservoir hosts5,6. The high genetic similarity between local L. major isolates and those from other regions, such as the UK (AF308685) and Iran (AB678349), suggests a common evolutionary origin and highlights the role of regional and international transmission networks in shaping the genetic landscape of Leishmania.

Similarly, the L. tropica isolates from human cases showed 100% identity to Iranian strains (AB678350, KM491168) and 99% identity to isolates from the UK (AF308689), Egypt (X84845), and Iraq (MF166796-800). The genetic homogeneity observed among L. tropica isolates aligns with previous reports from anthroponotic CL foci, where human-to-human transmission predominates. However, the absence of L. tropica detection in reservoir hosts in this study does not exclude potential zoonotic involvement, as our analysis was limited to a single genetic marker. Further studies incorporating multi-locus genomic data and expanded sampling of potential animal reservoirs are warranted to conclusively characterize transmission dynamics16,17.

The detection of L. infantum in human cases is particularly noteworthy, as this species is typically associated with visceral leishmaniasis (VL) in the Mediterranean basin18. The close genetic relationship between local L. infantum isolates and strains from Spain (EU437407) and Iran (AB678348) suggests possible introductions from VL-endemic areas, either through human migration or the movement of infected reservoir hosts, such as dogs. This finding highlights the need for enhanced surveillance to monitor the spread of L. infantum and its potential role in the emergence of atypical CL cases in southern Iran.

In implications for leishmaniasis control, the predominance of L. major in Shiraz underscores the importance of targeting zoonotic transmission cycles in CL control programs. Rodent control measures, such as habitat modification and the use of rodenticides, have been shown to reduce sand fly populations and interrupt Leishmania transmission in other endemic regions19. However, the effectiveness of these strategies depends on a thorough understanding of local reservoir ecology, including the distribution and behavior of key rodent species. In Shiraz, the widespread presence of Tatera indica in agricultural and peri-urban areas highlights the need for integrated vector and reservoir management, particularly in high-risk zones.

The detection of L. tropica in human cases also emphasizes the importance of addressing anthroponotic transmission, which is often associated with urbanization and poor housing conditions12. In Shiraz, rapid urban expansion has led to the proliferation of sand fly breeding sites, such as cracks in mud-brick houses and organic waste deposits, creating ideal conditions for L. tropica transmission. Public health interventions, including improved housing, environmental sanitation, and community education, are essential for reducing sand fly exposure and preventing the spread of ACL in urban areas.

The presence of L. infantum in human cases raises concerns about the potential overlap between CL and VL transmission cycles in southern Iran. While L. infantum is primarily associated with VL, its detection in CL cases suggests possible changes in parasite behavior or host-parasite interactions, possibly driven by environmental or genetic factors20. Further studies are needed to investigate the role of L. infantum in CL epidemiology and assess its impact on disease presentation and treatment outcomes.

In comparative analysis with previous studies, our findings are consistent with previous molecular studies on Leishmania in Iran, which have identified L. major and L. tropica as the dominant species in CL-endemic areas6,11. However, the detection of L. infantum in Shiraz represents a notable departure from earlier reports, which primarily focused on L. major and L. tropica. This discrepancy may reflect changes in Leishmania transmission dynamics, driven by factors such as climate change, urbanization, and human migration12. For example, a study in Isfahan reported the emergence of hybrid Leishmania strains with genetic material from both L. major and L. tropica, highlighting the potential for adaptive evolution and the emergence of novel genotypes14.

The high genetic similarity between local isolates and strains from other regions also aligns with findings from molecular studies in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, where Leishmania species often exhibit broad geographical distributions and high genetic homogeneity16. This pattern may reflect the historical movement of Leishmania parasites and their vectors across the region, facilitated by trade, migration, and ecological connectivity.

About limitations and future directions, while this study provides valuable insights into the genetic diversity of Leishmania in Shiraz, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample size was relatively small, particularly for isolates from rodents and sand flies, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, the study focused on a single genetic marker (minicircle kDNA), which, while informative, may not capture the full extent of Leishmania diversity. Future studies should incorporate additional genetic markers, such as the cytochrome oxidase (CoxI and CoxII) genes, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of Leishmania evolution and transmission21,22,23,24.

Further research is also needed to explore the role of other microorganisms, such as Wolbachia and Crithidia, in Leishmania transmission. These endosymbionts have been shown to influence sand fly vector competence and may play a role in shaping Leishmania epidemiology25. Additionally, studies on the immune responses of humans and reservoir hosts to Leishmania infection could provide insights into the mechanisms of parasite persistence and host susceptibility26.

Our findings contribute to the growing body of molecular epidemiological data on leishmaniasis in the Middle East and inform evidence-based strategies for disease control. By elucidating the genetic landscape of Leishmania in southern Iran, this study also lays the groundwork for future research on parasite evolution, host-parasite interactions, and the development of novel therapeutics and vaccines.

Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into the genetic diversity of Leishmania in Shiraz, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample size was relatively small, particularly for isolates from rodents and sand flies, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, the study relied on a single genetic marker (minicircle kDNA), which, while informative for phylogenetic comparisons, may not capture the full genomic diversity or evolutionary relationships of Leishmania species. Third, the analysis did not include phenotypic assessments of parasite virulence or host immune responses, which are critical for understanding clinical outcomes and transmission dynamics. These limitations highlight the need for future studies to integrate larger, multi-species sampling, multilocus genetic approaches (e.g., cytochrome oxidase genes), and phenotypic or immunological analyses to comprehensively elucidate the epidemiology of leishmaniasis in this region.

Conclusion

Implications for leishmaniasis control

The predominance of L. major in Shiraz (Fig. 3) underscores the importance of targeting zoonotic transmission cycles in CL control programs. Rodent control measures, such as habitat modification and the use of rodenticides, have been shown to reduce sand fly populations and interrupt Leishmania transmission in other endemic regions19. However, the effectiveness of these strategies depends on a thorough understanding of local reservoir ecology, including the distribution and behavior of key rodent species. In our study, the isolation of L. major from 85% of Tatera indica rodents sampled (see Results section) highlights their role as primary reservoir hosts in Shiraz, particularly in agricultural and peri-urban areas.

The detection of L. tropica in human cases (Fig. 4) also emphasizes the importance of addressing anthroponotic transmission, which is often associated with urbanization and poor housing conditions12. Our entomological surveys (Results section) revealed a 40% increase in Phlebotomus sergenti (the primary vector for L. tropica) densities in urban zones compared to rural areas over the past decade, supporting the hypothesis that rapid urban expansion has led to the proliferation of sand fly breeding sites, such as cracks in mud-brick houses and organic waste deposits. The presence of L. infantum in human cases (Fig. 5) raises concerns about the potential overlap between CL and VL transmission cycles in southern Iran. Phylogenetic analysis showed that local L. infantum isolates clustered with strains from Spain (EU437407) and Iran (AB678348), suggesting introductions from VL-endemic areas. Spatial mapping of cases (Results section) further identified hotspots of L. infantum near regions with high dog populations, implicating canine reservoirs in its transmission.

This study highlights the complex transmission dynamics of Leishmania in Shiraz, southern Iran, and underscores the importance of molecular epidemiological studies in guiding leishmaniasis control strategies. The predominance of L. major in human, rodent, and sand fly samples confirms the zoonotic nature of CL in this region, while the detection of L. tropica and L. infantum highlights the need for integrated control measures targeting both zoonotic and anthroponotic transmission cycles. The high genetic similarity between local isolates and strains from other regions suggests widespread transmission and potential introductions from neighboring areas, emphasizing the importance of regional collaboration in leishmaniasis control.

Data availability

Sequences are accessible in GenBank (MN179618–MN179622).

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Leishmaniasis: Epidemiology and control. WHO Technical Report Series (2020).

Majidnia, M. et al. Effect of flood on the cutaneous leishmaniasis incidence in northeast of Iran: An interrupted time series study. BMC Infect. Dis. 25(1), 15 (2025).

Merdekios, B. et al. Unveiling the hidden burden: Exploring the psychosocial impact of cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions and scars in southern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 20(2), e0317576 (2025).

Sabzevari, S., Teshnizi, S. H., Shokri, A., Bahrami, F. & Kouhestani, F. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Microb. Pathogen. 152, 104721 (2021).

Soltani, S., Foroutan, M., Hezarian, M., Afshari, H. & Kahvaz, M. S. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an epidemiological study in southwest of Iran. J. Parasitic Diseases 43(2), 190–197 (2019).

Ghatee, M. A. et al. Molecular epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran. Parasitol. Int. 67(6), 713–720 (2018).

Akhoundi, M. et al. A historical overview of the classification, evolution, and dispersion of Leishmania parasites and sand flies. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10(3), e0004349 (2020).

Kyari, S. Epidemiology of Leishmaniasis. Leishmania Parasites-Epidemiology, Immunopathology and Hosts. IntechOpen, (2024).

Moghaddam, Y. et al. Phylogenetic analysis and antimony resistance of Leishmania major isolated from humans and rodents. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 71(1), 89–98 (2024).

Azizi, K. et al. Molecular detection of Leishmania parasites and host blood meal identification in wild sand flies from a new endemic rural region, south of Iran. Pathog. Glob. Health 110(7–8), 303–309 (2016).

Nikookar, S. H. et al. Molecular detection of Leishmania DNA in wild-caught sand flies, Phlebotomus and Sergentomyia spp. in northern Iran. Parasite Epidemiol. Control 27, e00395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parepi.2024.e00395 (2024).

Ready, P. D. Epidemiology of visceral leishmaniasis. Clin. Epidemiol. 6, 147–154 (2014).

Menegatti, J. A. & Dias, Á. F. L. R. Epidemiology of visceral leishmaniasis in municipalities of Mato Grosso and the performance of surveillance activities: An updated investigation. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 33(1), e015623 (2024).

Karimi, T. et al. Hybridization in Leishmania: Implications for diagnosis and control. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 15(4), e0009273 (2021).

Sharifi, I. et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis situation analysis in the Islamic Republic of Iran in preparation for an elimination plan. Frontiers Public Health 11, 1091709 (2023).

Hamarsheh, O. et al. Genetic structure of Leishmania tropica in the Middle East. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6(2), e1509 (2012).

Silva, H. et al. Autochthonous Leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania tropica, identified by using whole-genome sequencing, Sri Lanka. Emerg. Infect. Diseases https://doi.org/10.3201/eid3009.231238 (2024).

Dujardin, J. C. et al. Spread of vector-borne diseases and neglect of leishmaniasis Europe. Emerg. Infect. Diseases 14(7), 1013–1018 (2008).

de Souza, W. M. & Weaver, S. C. Effects of climate change and human activities on vector-borne diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 22(8), 476–491 (2024).

Bañuls, A. L. et al. Leishmania and the leishmaniases: A parasite genetic update and advances in taxonomy, epidemiology and pathogenicity in humans. Adv. Parasitol. 64, 1–109 (2007).

Yadav, P. et al. Unusual observations in leishmaniasis—an overview. Pathogens 12(2), 297 (2023).

Ghafari, S. M. et al. Designing and developing a high-resolution melting technique for accurate identification of Leishmania species by targeting amino acid permease 3 and cytochrome oxidase II genes using real-time PCR and in silico genetic evaluation. Acta Trop. 211, 105626 (2020).

Darif, D. et al. Host immunopathology in Zoonotic Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: exploring the impact of the diversity of Leishmania major strains from two Moroccan Foci. Microb. Pathog. 202, 107414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2025.107414 (2025).

Hagedorn, N., et al. Quantitative proteomics of infected macrophages reveals novel Leishmania virulence factors. bioRxiv, 2025–01 (2025).

Volf, P. & Myskova, J. Sand flies and Leishmania: Specific versus permissive vectors. Trends Parasitol. 23(3), 91–92 (2007).

Ghatee, M. A. et al. Molecular epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran. Parasitol. Int. 67(6), 713–720 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful for the assistance of the vice-chancellorship for research and technology at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (SUMS). This study was an approved research project (Grant no.: 94-01-104-10873).

Funding

This research was funded by the SUMS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K. and K.A.; designed, analyzed data, and co-wrote the paper. M.H.M., Q.A., I.M., A.S., and S.S.; performed experiments and co-wrote the paper. K.A.; supervised the research.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kalantari, M., Azizi, K., Motazedian, M.H. et al. Phylogenetic insights into Leishmania species circulating among humans, vectors, and reservoir hosts in Shiraz, Southern Iran: implications for leishmaniasis control. Sci Rep 15, 18531 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03452-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03452-3