Abstract

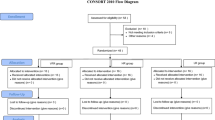

To use microcomputed tomography (micro-CT) to evaluate the porosity (%) of 3 M Pink Cavit (PC) and Riva Light Cure resin-reinforced glass ionomer (Riva RRGI) dental restoration when used over two types of spacers in Class II endodontically accessed premolars and investigate the effect of thermocycling on the porosity of the two biomaterials. Forty-four single-rooted human premolars were endodontically accessed, and a class II mesial box was prepared. Four experimental groups (n = 9) were defined based on the type of spacer and restoration used: PC and cotton pellet, PC and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), Riva RRGI and cotton pellet, and Riva RRGI and PTFE. In two control groups (n = 4), PC or Riva RRGI was used alone. All the groups underwent thermocycling. The porosity was measured before and after thermocycling using micro-ct. The results were analyzed using t-tests and one-way ANOVA with significance set at P < 0.05. Both PC and Riva RRGI exhibited inherent porosity, with porosity increasing after thermocycling (P = 0.015 and P < 0.001, respectively). Cotton pellets increased the percentage of the gap between the restoration and dental walls with both restoration materials before and after thermocycling. Thermocycling increased the porosity of both PC and Riva RRGI restorations. In Class II endodontic access cavities, spacer choice influenced gap formation, with PTFE proving to be a better alternative to cotton pellets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dental restoration quality is an important predictor of the success of non-surgical root canal treatment1. A quality restoration is essential to inhibit the re-entry of oral micro-organisms1. Additionally, it contributes to the objective of root canal obturation by entombing the remaining bacteria of the root canal system1. Temporary restorations are indicated for multiple-visit root canal treatments2. Multiple-visit root canal treatments are considered in several circumstances, including traumatic dental injuries, regenerative endodontic procedures, internal bleaching, treatment of complex endodontic anatomy, and long-standing periodontic and endodontic infection2. Poor quality temporary restoration is a major risk factor for persistent pain after endodontic treatment3. It permits secondary re-infection, which is a risk factor for flare-ups in multiple-visit endodontic procedures2,4. Accordingly, the quality of a temporary restoration can impact the success of non-surgical root canal treatment2,3.

Cavit and glass ionomer restorations have been recommended for temporizing endodontically accessed teeth2. However, a high percentage of clinicians detected temporary restoration deterioration or complete loss on the second endodontic treatment visit5. Temporary restoration fractures in endodontically accessed teeth were the most common adverse event that required urgent intervention during the COVID-19 pandemic6. These findings suggest the need to improve current standards for temporary materials. Since poor marginal sealing and mechanical properties of temporary restoration can compromise treatment outcomes3. In-vitro studies suggested that the Cavit had adequate micro-leakage resistance but displayed poor mechanical properties and retention2,7. In contrast, resin-reinforced glass ionomer restoration (RRGI) can be described as an exceptional temporary restoration2. Compared with Cavit, it shows comparable leakage resistance, good mechanical properties, acceptable aesthetic quality, and satisfactory retention2,8,9.

Riva’s Light Cured Resin Reinforced Glass Ionomer (Riva RRGI) (SDI Limited, Victoria, Australia) has exceptional aesthetic, chemical, and physical properties10. The material is indicated for long-term and temporary restorations10. Riva RRGI is composed of bioactive glass containing a blend of highly reactive glass particles of varying sizes combined with fluoride and strontium ions10. Clinical findings suggest that Riva RRGI is highly durable, with retention and marginal adaptation comparable to those of resin-based composites11. However, 3M Pink Cavit (PC) (3M, Minnesota, USA) is easy to handle and suitable for temporizing accessed root canal systems12. PC is composed mainly of zinc oxide mixed with calcium salts that provide a bacterial tight seal through fluid expansion. Recent microleakage studies showed that Cavit’s performance can be material dependent13,14. These studies assessed fluid infiltration or bacterial penetration in vitro models13,14 but never compared PC to RRGI using micro-CT scanning. Moreover, thermocycling simulates temperature changes in the oral environment, which can affect the evaluation of dental restoration7,15,16. Therefore, thermocycling is an important factor in the evaluation of longevity and durability of temporary dental restorations, especially in class II dental restoration7,15,16.

Posterior teeth with Class II cavities represent a clinical challenge in restorative dentistry17,18,19. The gingival floor of class II cavity preparation is situated close to the gingival crevice17,18. The gingival floor area is marked by its humidity and the difficulty of isolation and manipulation17,18. The area also lacks sufficient enamel for satisfactory bonding with resin-based restorations17,18. Moreover, gingival crevicular fluid is populated with oral bacteria and their by-products, risking the re-contamination of the accessed root canal system20,21. The canal orifices in endodontically accessed teeth with Class II cavities are often located adjacent to or below the gingival floor, although this may vary depending on the tooth’s anatomy. Cotton fibers were trapped under a Cavit restoration in a Class II preparation when a cotton pellet was used as a spacer22. However, another study found that a well-situated cotton pellet might not affect restoration sealability19. Cotton pellets and Cavit are the most common spacer and temporary restoration combinations for multiple-visit endodontic treatment5,23.

Spacer materials are used to prevent iatrogenic accidents in endodontic re-entry and facilitate the removal of temporary restorations5,5,23,23. Spacer materials are indicated primarily for in between dental visits to prevent dislodgement of the temporary filling material placed over the empty root canal5. Although the cotton pellet is the most widely used spacer material, it has several disadvantages5,23. Cotton pellets can act as a reservoir for bacteria in the event of microleakage and may also function as a cushion beneath the temporary restoration, potentially compromising the seal and leading to dislodgement or breakdown of the temporization material24,25,26. Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) has been recommended as an alternative to cotton pellets for temporary restorations24,25. One key advantage is that PTFE is an inert material that does not support bacterial growth25,26. Additionally, unlike cotton pellets, PTFE is not spongy in consistency, which may contribute to a more stable temporization seal25. In previous research, when cotton pellets were compared to PTFE in Class I preparations restored with Cavit, restoration gaps were observed more frequently in the PTFE samples25. This study aims to further explore the role of spacers in maintaining the internal marginal seal of Class II endodontically accessed teeth. We define Class II endodontically accessed teeth as those where the Class II cavity extends into the endodontic access, creating a configuration that combines both the proximal cavity and the access preparation27,28,29.

Additionally, the study aimed to explore how spacer materials might influence different restorations after thermocycling. These new parameters will enhance our understanding of the relationship between the choice of restorative material, the type of spacer used, and the impact of thermocycling on the porosity of temporary restorations. Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) allows non-invasive evaluation of the quality and porosity of dental restorations25,30. Porosity consists of voids within the restoration and gaps between the restoration and dental walls25,30. High porosity can compromise the durability and integrity of a dental restoration31. Porosity shapes the microstructure of materials by affecting their mechanical properties and influences their interaction with external factors such as sorption, diffusion, and thermal exchange32. Thus, investigating the porosity of dental materials is essential to understanding their mechanical behavior, especially when they are exposed to oral fluids32,33,34,35. The porosity of temporary restorations when placed over two different types of spacers in Class II endoscopically accessed cavities has yet to be thoroughly studied.

This study aimed to compare the percentage of porosity of PC and Riva RRGI restorations placed over a cotton pellet or polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) spacer in Class II endodontic access cavities. Micro-CT was used to evaluate the porosity of both dental materials before and after thermocycling. The null hypotheses were (1) there is no significant difference in the porosity of PC and Riva RRGI, (2) the type of spacer material does not influence the porosity, and (3) thermocycling does not affect the porosity of these restorations as assessed by micro-CT imaging.

Material and methods

The study was registered in the dental school of Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University (PNU). The experiment was approved by PNU’s institutional review board (IRB: 23-0118) and all methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations. The experiment involved the use of extracted natural human teeth. All of the patients or their legal guardians signed general informed consent forms allowing all of their dental records to be anonymously used for education or research purposes. All the patients or their legal guardians also provided informed consent to oral surgery treatment before dental extraction for orthodontic and periodontic reasons. The PNU IRB waived the need for informed consent for collecting the teeth after extraction provided that these teeth were collected anonymously and otherwise would be discarded.

Sample size calculation

The appropriate sample size was calculated to determine the statistical power of this in vitro study, utilizing the comparison of two independent means based on prior studies36. These studies investigated the porosity in RIVA glass ionomer and PC restorations using micro-CT25,37. The Riva glass ionomer restoration exhibited a mean porosity of 0.42%, with a standard deviation of 0.4%37. In contrast, the mean porosity for the PC restoration was 2%25. The desired power was 95%, and significance levels were set at a 95% confidence interval and 0.5 significance level. Accordingly, the experimental subgroup comprised 9 teeth. To establish a baseline for comparison with the experimental groups, two control groups were incorporated, each consisting of 4 teeth. The total sample size was 44 teeth.

Teeth selection and allocation

Teeth that were extracted for orthodontic or periodontic reasons were collected anonymously, providing that the patient consented to such treatment. The collected teeth were cleaned using an ultrasonic scaler and water spray and then stored in a sealed container in a 1% sodium hypochlorite solution. Forty-four extracted, human, single-rooted premolars were selected after they were visually and radiographically examined under 10.0× magnification using a dental microscope (Global microscope, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and a periapical radiograph.

Only intact, single-rooted teeth and minimally carious teeth with no restorative defects or detectable cracks were included. The average tooth length and buccolingual and mesiodistal dimensions were estimated, and the distances from the buccal cusp to the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) and from the mesial marginal ridge to the CEJ were measured. The exclusion criteria were teeth that were smaller or larger than the calculated averages and teeth that had an abnormal morphology, open apex, or calcified pulp chambers or root canals. The appropriateness of the selection was further confirmed after the initial micro-CT scan.

Subsequently, the teeth were randomly divided into six main groups: four experimental groups with nine teeth each (group 1: cotton pellet and PC; group 2: PTFE pellet and PC; group 3: cotton pellet and Riva RRGI; group 4: PTFE pellet and Riva RRGI) and two control groups with four teeth each (group 5: PC alone; group 6: Riva RRGI alone).

The access cavity and root canal preparation

One operator prepared a standard endodontic access cavity on the occlusal surface. The access burs were an ISO size 014 round Carbide bur for occlusal entry, followed by a long shank Endo Z bur for de-roofing38. The entry point was 1 mm buccal to the central fossa, and the occlusal opening was lingually extended to the central groove to establish straight-line access to the root canal38. After complete de-roofing of the pulp chamber, the canal was located, and measurements were taken from the entry point to determine access length. The occlusal cusp was reduced to standardize the length of the access cavity to 6 mm from the point of entry to ensure standardization of the procedure. This also provided the recommended 3.5 mm minimum space needed for temporary restoration following the placement of spacer material39. Afterward, a standardized Class II OM cavity was prepared with diamond burs following the protocol and dimensions used in Atalay et al.40 The subgingival floor was situated 1 mm above the cementoenamel junction, and the measurements of the internal walls were prepared based on the distance between the external walls (Fig. 1)40. The access burs were replaced after the fourth cavity preparation throughout the process40.

The figures illustrate the prepared endodontic access and Class II configuration in single-rooted premolars, as well as the location and size of the spacers used: (a) Occlusal view showing the endodontic access and Class II configuration. (b) Mesial view of the same preparation. (c) The guide was used to standardize the size of the PTFE spacer, ensuring it matched the size of a size 4 cotton pellet. The guide is a cotton-pellet-shaped resin mold. (d) PTFE is used as a spacer in the accessed endodontic cavity.

The root canals were shaped to working length using the sequence and technique recommended for ProTaper Gold rotary files (Dentsply Sirona, Charlotte, North Carolina, USA). After estimating the working length in the radiograph, the canals were negotiated with size 10 and 15 K files to the working length to create the glide path for the rotary files. The X-SMART Endo Motor was adjusted to the desired manufacturer-recommended settings in continuous rotation motion (Dentsply Maillefer, Switzerland). Then the canals were shaped using shaper S1 and shaper S2, and the shaping was completed with finisher F1. Following the manufacturer’s recommendations, the rotary files were replaced after the shaping of every four canals to avoid fatigue and fracture. The canals were irrigated during the shaping procedure using 2.5% sodium hypochlorite (Prime Dental Products, India). Finally, the root canals were dried using F1 paper points (Dentsply Sirona, Charlotte, North Carolina, USA).

Preparation of PTFE pellets

A previously published approach was followed25. The PTFE pellets were created using a size 4, cotton-pellet-shaped resin mold (PTFE thread seal tape, ACE, Illinois, USA). To make size 4 pellets, PTFE tape was cut into 2 cm pieces that were placed in the mold and adjusted. Thus, the spacers would have a standard thickness of around 2 mm and allow for a temporary restoration thickness of at least 3.5 mm.

Temporization

The spacers were inserted in the four experimental groups (1, 2, 3, and 4) over the canal orifices. The manufacturer’s instructions were followed for material preparation and manipulation (Table 1).

A Glick 1 instrument was used to perfectly situate the spacer over the canal orifice and push the spacer below the mesial gingival floor (Premier Dental Group, Minnesota, USA). The Glick was also used to carry a small amount of PC to place it over the spacer in two increments and gently condense it until the access cavity was filled. The excess was removed using a plastic instrument or probe to ensure that the filled cavity was homogenous with the external dental walls. A moist cotton pellet was gently applied to the external surface of the Pink Cavit (PC) to aid the initial setting. The teeth in Groups 1 and 2, restored with PC, were then stored for two to four hours in a semi-wet environment using a moist piece of gauze with a few drops of distilled water. This step was essential to allow sufficient setting and hardening of PC, as the material sets through water sorption and requires several hours to harden completely (Table 1)41.

Riva RRGI was used in this experiment, and the manufacturer’s instructions were followed. The dental walls in groups 3 and 4 were conditioned using RIVA conditioner for ten seconds and then washed with water and air-dried to remove the excess water. Dry spacers were inserted after the excess water was removed. Then the Riva RRGI capsule was pressed down and mixed in an SDS Kerr 4000 triturator for ten seconds (KaVo Kerr, California, USA). The Riva RRGI capsule was placed in the capsule applicator, which was triggered to extrude the Riva RRGI. The Riva RRGI was placed directly over the slightly moist conditioned dentin surface in 2-mm increments and light-cured for 20 s after each increment using a Translux Wave (Kulzer, Mitsui Chemical Group, Hanau, Germany). The power density of the light cure device was less 1200 mW/cm2, and the wave length was set to 440–480 nm. All of the teeth in the experiment needed only two 2-mm applications to fill the prepared cavity. The Riva RRGI excess was removed using a plastic instrument or explorer to ensure that the filled cavity was homogenous with the external walls before the final light cure.

The control groups were directly restored with PC and Riva RRGI using the same techniques but without spacers. Finally, in all groups, the apex of each tooth was covered with a double layer of transparent nail polish to prevent water leakage through the apical foramen. The teeth were placed in colored and number-coded containers to track their progress throughout the experiment. The teeth were stored in a semi-wet environment using a moist piece of gauze with a few drops of distilled water to simulate oral conditions.

Micro-CT evaluation and calculation of the percentage volume of gaps and voids

Each tooth underwent three micro-CT scans during the experiment. The first scan assessed the suitability of the teeth for the study design. The second scan was performed post-temporization, and the third scan took place after thermocycling.

For each scan, the teeth were placed in Eppendorf tubes. A few drops of distilled water were added to prevent excessive dryness and overheating during the process. The tubes were then secured on foam to ensure they remained stable throughout the scanning. The teeth were scanned using the Bruker SkyScan 1176 micro-CT scanner (Bruker Corporation, Massachusetts, USA) set to the following parameters: 80 kV, 124 mA, 15.57 µm pixel size, 360° rotation, 0.5° rotation steps, and a 250-ms exposure time.

The Bruker SkyScan software package was utilized for data analysis, including NRecon for image reconstruction, DataViewer for 3D inspection, CTAN (v.1.22.3.1) for 3D image analysis, and CTVOX (v.3.3.1) and CTVOL (v.2.32.2) for 3D visualization. NRecon v.1.7.5.9 was used to reconstruct the raw images; we applied a 15% beam hardening correction, a five-ring artifact correction, and a − 4.5 misalignment adjustment. Next, CTAN was employed to segment the restorative material within the access preparation and assess any associated porosity. The software quantified the restoration’s volume (in mm3) and porosity and analyzed the percentage of radiopacity and radiolucency within the 3D volume.

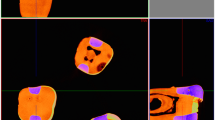

The region of interest (ROI) was defined from the beginning of the restoration within the mesial box of the Class II cavity to the termination of the mesial marginal ridge and identified in the axial plane for each scan. Figure 2a, d illustrates the axial plane raw images within the ROI. The restoration in the Class II access cavity was outlined using a polygonal shape in each 2D image, capturing the gap around the restoration and any voids in the material (Fig. 2b and e). The outline was adjusted across multiple axial images to account for changes in the material’s geometry, resulting in a comprehensive 3D outline of the restoration and any marginal gaps in the cavity space.

The process of outlining and analyzing the selected area of interest. (a and d) Are raw images of two teeth at different levels (the yellow arrows point to the gap at the restoration periphery and the green arrow points to the void in the restoration). (b and e) Outline the restoration with the gap to calculate the porosity percentage. (c and f) Outline the restoration alone to calculate the percentage of voids (the yellow arrows point at the gap that was excluded from the outline). (g) Compares the number and sizes of the pores in the binary image of the outlined area with those seen in the raw image of the restoration to confirm the suitability of the threshold at different levels.

Thresholding of the binary image was established by comparing it with the raw image, considering both the number and size of the voids in the restoration (Fig. 2, g). The thresholding values ranged from 85 to 160, with an average of 113. The despeckle option was applied to distinguish voids from minor radiographic artifacts in the 3D reconstruction. The software automatically calculated the percentage of radiopaque mass within the outlined ROI, while the porosity percentage was defined as the total volume of gaps and voids in the restoration.

The term “gap” was used to refer to the space between the restoration and the cavity wall, while “void” referred to areas lacking material in the restoration itself. The porosity was defined as the percentage of void and gaps, therefore the restoration with a surrounding gap was initially outlined and the percentage of porosity was analyzed (Fig. 2b and e). To calculate the percentage of voids, the restoration was redrawn, excluding the surrounding gap (Fig. 2c and f). This allowed for a void percentage calculation using the same threshold. The percentage of gaps was then calculated by subtracting the void percentage from the total porosity.

Each tooth’s scan was coded to track progress across all three scanning phases. A blinded, trained micro-CT analyst, unaware of the study objectives, conducted all scans and analyzed the images under dim lighting conditions. Finally, CTVol was used to create realistic 3D models. CT Vox enabled volume rendering, adding depth and clarity to the 3D images (Fig. 3).

Direct comparison of the experimental and control groups using three-dimensional imaging and modeling before and after thermocycling. The three-dimensional imaging shows the coronal plane between the spacer and restoration, as well as the large voids in the PC restoration that resemble cracks and their concentration in the mesial box. The three-dimensional modeling shows the structure of the restoration, focusing on the concentration of voids before and after thermocycling (the restoration is gray-white, and the gap and void are green). The voids appear to be concentrated on the external surface of the tooth or above the gap between the restoration and spacer. In the absence of a spacer, the voids appeared to be concentrated only on the external surface.

Thermocycling evaluation

The teeth underwent aging by thermocycling through the application of 5000 cycles at 5 °C and 55 °C, with a 20-s dwell time and 3 s transfer time between baths42,43. All specimens underwent thermocycling within the same time frame. Immediately afterward, they were tracked, recorded, and prepared for rescanning using micro-CT. All teeth were rescanned within a one-week period to maintain consistency in data acquisition.

Statistical analysis

The results were analyzed using IBM SPSS 29 (SPSS Inc., Illinois, USA). The dataset was evaluated to ensure the suitability of parametric tests. Lavene’s test was used to determine the equality of variance. Subsequently, a t-test was employed to compare mean values between independent groups, focusing on the Riva RRGI and PC restorations across the three criteria: the percentages of porosity, voids, and gaps. The comparison of experimental and control subgroups was conducted using one-way ANOVA, followed by a post-hoc test to pinpoint between-group differences. The significance level for all tests was set at 0.05.

Results

The Riva RRGI and PC dental restoration subgroups were compared before thermocycling and the findings are summarized in Table 1. Their values were similar, with few exceptions. However, when PTFE was used as a spacer, the Riva RRGI restorations were significantly less porous and contained a significantly lower percentage of voids than the PC restorations (P = 0.037 and P = 0.033, respectively).

When the PC experimental subgroups were compared to the control PC group before thermocycling (Table 2), the percentage of the gap in the cotton subgroup was significantly more than in the control groups (P = 0.012). However, the percentages of void and gap in the PTFE subgroup were comparable to the PC control group (P = 0.218 and P = 0.131 respectively). Overall porosity was significantly greater in the PTFE subgroup than in the PC control groups (P = 0.040).

The Riva RRGI experimental subgroups were compared to the control Riva RRGI group before thermocycling (Table 2). The porosity and gap percentage in the cotton subgroup were significantly greater than in the control groups (P = 0.039 and P = 0.007). However, the porosity and void and gap percentages in the PTFE subgroup were comparable to those in the glass ionomer control group (Table 2).

After the thermocycling, the experimental groups of Riva RRGI and PC had comparable values for porosity, gaps, and voids when used over cotton pellets or PTFE. The results were compared using a t-test and summarized in Table 3. When the cotton subgroups were compared to control groups using the same restoration material, there was a significant increase in the percentage of the gap in the PC groups (P = 0.048). Additionally, a significant increase in the percentages of voids and gap was noted in Riva RRGI (P = 0.006 and P = 0.011, respectively) (Table 3). However, when the PTFE subgroups were compared to control the subgroups that received the same restoration without PTFE, there was no significant increase in the percentage of porosity, voids, and gaps in PC and Riva RRGI.

When the control groups were directly compared before and after thermocycling, both materials had similar percentages of porosity, voids, and gaps. The PC control group had slightly higher mean values than the experimental group before thermocycling, while the Riva RRGI control group had slightly increased mean values compared to PC after thermocycling (Tables 2, and 3).

Finally, the percentage porosity of PC and Riva RRGI were compared before and after thermocycling using an independent sample t-test. Interestingly, the porosity of PC and Riva RRGI increased after thermocycling (P = 0.015, P < 0.001 respectively). Additionally, the percentage of voids increased after thermocycling in PC (P = 0.21) and Riva RRGI (P < 0.001). In contrast, the gap percentage was less affected in both PC (P = 0.512) and Riva RRGI (P = 0.743). The findings of experimental and control groups for PC and Riva RRGI are shown in Figs. 4 and 5.

Discussion

The voids or closed pores encapsulated within the material matrix were attributed to insufficient gas evolution during the chemical reaction44. Zdravok and colleagues consider that voids affect the mechanical properties of the materials44. However, they exclude the effect of voids on material permeability44. They consider gaps or open pores that are accessible to the surrounding material to be responsible for the exchange of ions and molecules with the environment44. However, these assumptions are speculative and need to be confirmed in further research before they can be generalized to different materials and environments. Pores were also classified based on their porosity geometry, and certain geometrical shapes were associated with certain materials44. The RRGI had spherical, evenly distributed pores that were disconnected from each other. In contrast, the pores in the PC were irregular in shape, with many large pores exemplifying cracks in the restorations. These cracks were mainly located near the missing mesial wall of the Class II configuration. Such cracks represent a weak point because they can propagate, leading the restoration to fracture. The connections between the irregular pores could reflect the heterogeneity of the material and its exposure to ion exchange with the external environment44.

In our comparative analysis, the percentage of voids in Riva RRGI and PC increased after thermocycling, but the percentage of gaps remained similar. Both Riva RRGI and PC are intended to be susceptible to water sorption for different reasons. Riva RRGI is designed to release fluoride when interacting with the humid oral environment45,46. The fluoride release and ion exchange in the oral environment is expected to last for weeks to months with a possibility of fluoride recharge45,46. The manufacturer of Riva RRGI claims that the cumulative effect of fluoride release reaches its peak in the sixth week. The setting process undergone by Riva RRGI consists of an acid–base reaction with auxiliary photo-polymerization46. The acid–base reaction results in the early, rapid release of fluoride and micro-mechanical adhesion to enamel and dentin. The early release of fluoride is followed by a steady, low-level release of fluoride through the process of diffusion46. The fluoride ions trapped in the material matrix diffuse to the oral fluid through the pores and cracks46. The presence of HEMA in RRGI improves the micromechanical interlocking between the glass ionomer and the dental walls8. The fluoride release of Riva RRGI was found to be similar to that from conventional glass ionomer, with the ability to reabsorb fluoride from the oral environment45,46.

However, Pink Cavit (PC), a type of Cavit restoration, is a hygroscopic material that absorbs water until it reaches equilibrium, where the amount of absorbed moisture equals the amount of moisture lost41. The hydration induces the setting reaction, which involves the zinc oxide and accelerators in the material matrix41. A state of polymerization and hardening with a process of linear expansion follows41. The setting of the material takes a few hours, and the material relies on mechanical retention to hold onto the tooth structure41. The linear expansion process further adapts the material to the dental undercuts or irregularities and improves the sealing of interfacial gaps between the material and dentin41,41. However, it induces crack formation and propagation in the Cavit and the surrounding dental structure47,48. Furthermore, the mechanical properties of Cavit restoration are unsatisfactory41. Thermocycling and mechanical loading cause Cavit to collapse in endodontically accessed cavities7.

Water sorption may allow bacteria and their toxins to pass through restorative materials21 .It also weakens their mechanical properties and negatively affects their wear resistance and aesthetics49,50,51. In this study, Riva RRGI appeared to be sensitive to thermocycling; clinically, however, secondary or recurrent caries are rarely frequent around RMGI restorations9. One explanation is that water sorption causes linear expansion that improves the marginal seal of dental polymers such as composites, compomers, and RMGI52. Hygroscopic expansion relieves shrinkage stress, which could further explain why the gap percentage was not affected by thermocycling52. In addition to permeability, it is important to consider the hospitability of the restorative environment to oral bacteria53. Riva RRGI appeared to hold antibacterial properties, while the antibacterial properties of the Cavit need to be investigated53. Cavit restorations are known for fast deterioration and poor retention, especially in Class II cavity preparation5,7,48. PC, the type of Cavit tested in this study, maintained its integrity, as none of the PC subgroups experienced restoration loss after thermocycling. However, cracks were visible in the restorations, especially in the mesial box of the class II access cavities. PTFE appears to allow better adaptation of temporary restorations; this will be especially helpful with materials such as Cavit restorations that rely on mechanical retention. Moreover, reducing the gap between the material and the spacer is a wise objective to decrease the risk of micro-leakage around the restoration.

The experiment included thermocycling to simulate the thermal conditions of the oral cavity on the restorative materials being tested. Temperature fluctuations in the mouth cause restorative materials to expand and contract, potentially leading to their aging and shrinkage54. Thermocycling can promote defects along the restorative margin by inducing crack propagation or altering gap dimensions54. In this study, micro-CT was used to noninvasively assess the marginal gap of two temporization materials in Class II restorations. No significant increase in gap size was observed after thermocycling. Riva RRGI and PC demonstrated acceptable marginal adaptation after being subjected to 5000 thermocycles to simulate 6 to 12 months of oral function16.

Although Cavit is intended for short-term use, subjecting it to 5000 cycles provided valuable insights into its behavior under exaggerated thermal stress, making the results comparable to findings from other studies13,16. Notably, a recent 2023 publication recommended the use of extended thermocycling and micro-CT analysis to assess the performance of temporary restorations under simulated clinical conditions13. Interestingly, Cavit G was the least soluble temporary restorative material and demonstrated the highest microhardness compared to other temporary materials55. This durability could be attributed to the high coefficient of thermal expansion in zinc oxide-eugenol materials55,56. Additionally, there appears to be a correlation between ease of handling and sealing ability55,56. PC, being premixed and hydrophilic, allows for easy placement in endodontic access cavities, reducing manipulation errors55,56.

In this study, Riva RRGI showed comparable porosity to PC, despite their different setting reactions. While RRGI generally exceeds the physical properties of zinc oxide-based materials, its setting reaction increases the risk of debonding due to adhesive failure or polymerization shrinkage56. Cavit’s premixed nature and its setting reaction resulted in exceptional marginal seals in dye filtration studies56. However, another study that used the filtration method with 99mTcNaO₄ and nuclear medicine imaging found that Cavit, compared to Ketak Silver and IRM, had the highest infiltration even though only 500 thermocycles were used13. Interestingly, that study recommended that future studies use extended thermocycles and micro-CT for better resolution and accuracy13. The filtration method primarily detects fluid micro-movement, which may overemphasize surface-level penetration. In contrast, micro-CT captures voids and gaps within and around the restorative material. Nonetheless, testing temporary materials under various conditions and experimental designs will enhance the understanding of their properties and clinical performance.

Although Cavit demonstrated an acceptable marginal seal, it requires sufficient thickness to withstand occlusal forces55. Occlusal stress poses a significant threat to Cavit’s stability, especially when the material is placed over a cotton pellet7,55. Therefore, the spacer beneath Cavit should be solid and thin enough to adequately support the material while still allowing for a proper marginal seal between it and the Class II proximal box55.

PTFE significantly reduced the space available to the dental spacer and possibly decreased the gap between the spacer and dental material. With both PC and Riva RRGI, the gap percentage when PTFE was used was comparable to that in the control groups that lacked a spacer, and this was the case before and after thermocycling. The gap percentages in the cotton subgroups were greater than those in the control groups in both situations. A similar finding was reported in our earlier study on Class I Cavit restorations, in which the gap was influenced by the type of spacer used25. The voids in Cavit restoration were less affected by the type of spacer25. As gaps are open pores that are regarded as responsible for ion exchange and micro-leakage of bacteria or their toxins, the choice of spacer appears to be an important factor that influences the adaptability of the materials and perhaps their mechanical retention44. This is especially true for Cavit material that relies on mechanical retention rather than the chemical and micro-mechanical bonding that occurs in RRGI restorations.

Interestingly, PTFE appears to reduce porosity and voids in Riva RRGI before thermocycling, compared to cotton pellets. However, porosity and voids increased after thermocycling in the same subgroup. A possible explanation is that as the amount of Riva RRGI restoration increased, fluoride release and exchange increased, causing increased voids and porosity. Since the gap percentage in the same subgroups was not affected by thermocycling, it seems that these spherical voids are primarily responsible for the ion release and exchange in the RRGI.

The gaps in this study were mainly located in the cervical area beside the mesial box. Thus the porosity values were influenced by the study design and cannot be compared to those obtained in studies with different designs. The porosity of the Cavit restoration appears to have been lower than that reported in a previous study of Class I access cavities25. When the percentage of pores was studied in Riva glass ionomer discs, porosity in those studies approached the percentage of voids in this study because the latter focused on the material, ignoring the gap surrounding it within the access cavity37,57. For example, discs of Riva RRGI appeared porous, with a lower porosity percentage than recorded in this study but approaching the level of the percentage of voids in the Riva RRGI control group before thermocycling37. Another study investigated the porosity of Riva RRGI under a scanning electron microscope57. The percentage of pores was the same as the percentage of voids in the Riva RRGI control group before thermocycling57. Porosity appears to be extremely low in porcelain and ceramic materials, reflecting their mechanical, physical, and aesthetic properties32.

Micro-CT is a non-invasive method for comparing PC and Riva RRGI over different spacers and assessing the porosity of dental restorations, including internal and external voids30,32,58. It offers a reliable way to measure porosity by analyzing X-ray attenuation in 3D images25,44. However, micro-CT study has several limitations, including the inability to differentiate between pores and cracks within the restoration. Cracks within Cavit restoration after setting are reported in the literature and were observed in this study48. One study suggested differentiating between cracks and voids based on the size of the pores in micro-CT imaging37.

Another limitation of this study is that micro-CT cannot differentiate between a space that is occupied by a spacer and the gap between a restoration and a spacer. We attempted to solve this problem by ensuring that the spacer was well placed below the gingival floor before applying the restoration. Additionally, the area of interest was selected to start at the beginning of the gingival floor in the Class II mesial box to exclude the area occupied by the spacer from consideration in the image analysis. Micro-CT imaging software will quantify the gaps and voids within and surrounding the temporary material or any further input requiring quantitative data30,58. Qualitative data can be obtained indirectly through image scrutinizing47. Interestingly, the correlation between the porosity and the physical and mechanical properties of dental restorations is yet to be explored. Moreover, the clinical relevance and impact of using highly porous restoration materials on the development or persistence of periapical lesions have not been fully examined.

Future research could combine microbial analysis with micro-CT imaging to provide a more comprehensive understanding of micro-CT findings. Previous studies have shown that PTFE performs better than cotton pellets as a spacer material in preventing microbial contamination24,26. Incorporating microbial analysis would further enhance the clinical relevance of voids, gaps, and overall porosity in temporary restorations. Micro-CT analysis indicates that total porosity is the sum of gap and void percentages, which explains how similar overall porosity can be observed between groups despite variations in gap and void distribution25. Integrating microbial analysis could also help determine whether overall porosity, voids, or gaps play the most critical role in influencing microleakage.

The major limitation of in-vitro studies is their clinical validity because they are performed in controlled and simplified environments59. However, they allow researchers to control variables and compare different materials’ properties59,60. Thus in vitro experiments can suggest the presence of a cause-and-effect relationship between independent and dependent variables60. The findings of this study provide valuable insights that can be correlated with clinical conditions. The observed increase in porosity and gap formation after thermocycling highlights the potential for compromised marginal adaptation in temporary restorations over time, which may increase the risk of bacterial infiltration and endodontic failure. Additionally, the impact of spacer selection on gap formation suggests that the choice of spacer material can influence the marginal seal. An attempt was made to simulate clinical conditions through thermocycling; however, mechanical loading was not performed due to a previous study reporting Cavit collapse after loading7.

Since the primary objective was to assess the porosity of both materials, mechanical loading was excluded. Future studies can explore Cavit retention after mechanical loading and thermocycling in various cavity preparations. Differentiating between the cracks and voids in the dental restoration based on their size and shapes in micro-CT is also advised, given that the literature suggests that porosity could affect the mechanical and physical properties of dental restorative material, particularly when studied in simulated oral conditions49,51,52. Moreover, the influence of materials commonly placed beneath spacers, such as calcium hydroxide used as intracanal medication or sodium perborate in internal bleaching procedures, was not evaluated. These materials may alter the restorative material’s properties or impact porosity and gap formation. Furthermore, mechanical behavior assessments, such as fatigue survival and brushing tests, were not conducted61. These factors could affect the long-term performance of temporary restorations under clinical conditions61. Future studies incorporating these variables would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the behavior of temporary materials and spacer interactions. Finally, the investigation can be further replicated in vivo and in clinical studies to confirm the clinical relevance of the findings and their contribution to the literature59.

Conclusion

Considering the study’s limitations and the parameters of this experimental design, the first null hypothesis, which stated that there is no significant difference in the porosity of PC and Riva RRGI, was accepted. However, the second and third null hypotheses, which proposed that the type of spacer material and thermocycling do not influence porosity and gap percentages, were rejected.

The following conclusions were drawn:

-

1.

Both PC and Riva RRGI dental restorations exhibited inherent porosity, with thermocycling intensifying their porous nature. Notably, the voids within the restorations increased after thermocycling, while the gaps were relatively less affected.

-

2.

Before thermocycling, when PTFE was used as a spacer, Riva RRGI demonstrated lower porosity and a smaller percentage of voids compared to PC. However, these values increased post-thermocycling, aligning with those of the PTFE and PC subgroups.

-

3.

The choice of spacers had a notable influence on the percentages of gaps in both restorations. The use of cotton pellets beneath both restorations led to the largest gap percentages and the absence of a spacer, the smallest. Gap percentages when PTFE was used were comparable to those in the no-spacer groups

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gillen, B. M. et al. Impact of the quality of coronal restoration versus the quality of root canal fillings on success of root canal treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Endod. 37, 895–902. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2011.04.002 (2011).

Naoum, H. J. & Chandler, N. P. Temporization for endodontics. Int. Endod. J. 35, 964–978 (2002).

Abbott, P. V. Factors associated with continuing pain in endodontics. Aust. Dent. J. 39, 157–161 (1994).

Siqueira, J. F. Microbial causes of endodontic flare-ups. Int. Endod. J. 36, 453–463 (2003).

Algahtani, F. N. et al. Common temporization techniques practiced in Saudi Arabia and stability of temporary restoration. Int. J. Dent. 2021, 4965500 (2021).

Patel, B., Eskander, M. A. & Ruparel, N. B. To drill or not to drill: Management of endodontic emergencies and in-process patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Endod. 46, 1559–1569 (2020).

Mayer, T. & Eickholz, P. Microleakage of temporary restorations after thermocycling and mechanical loading. J. Endod. 23, 320–322 (1997).

Almuhaiza, M. Glass-ionomer cements in restorative dentistry: A critical appraisal. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 17, 331–336 (2016).

Sidhu, S. K. Clinical evaluations of resin-modified glass-ionomer restorations. Dent. Mater. 26, 7–12 (2010).

SDI Limited. riva light cure / riva light cure HV - SDI. SDI website https://www.sdi.com.au/en-eu/product/riva-light-cure/ (2017).

Koç-Vural, U., Kerimova-Köse, L. & Kiremitci, A. Long-term clinical comparison of a resin-based composite and resin modified glass ionomer in the treatment of cervical caries lesions. Odontology https://doi.org/10.1007/S10266-024-00958-6/METRICS (2024).

3MTM CavitTM Temporary Filling Material Refill Jar (28g) (Red), 44030 | 3M Saudi Arabia. https://www.3m.com.sa/3M/en_SA/p/d/v000075974/.

Paulo, S. et al. Microleakage evaluation of temporary restorations used in endodontic treatment—An ex vivo study. J. Funct. Biomater. 14, 264 (2023).

Wuersching, S. N., Moser, L., Obermeier, K. T. & Kollmuss, M. Microleakage of restorative materials used for temporization of endodontic access cavities. J. Clin. Med. 12, 4762 (2023).

Gilles, J. A., Huget, E. F. & Stone, R. C. Dimensional stability of temporary restoratives. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 40, 796–800 (1975).

Morresi, A. L. et al. Thermal cycling for restorative materials: Does a standardized protocol exist in laboratory testing? A literature review. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 29, 295–308 (2014).

Christensen, G. J. Overcoming the challenges of class II resin-based composites. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 137, 1021–1023 (2006).

Dablanca-Blanco, A. B. et al. Management of large class II lesions in molars: How to restore and when to perform surgical crown lengthening?. Restor. Dent. Endod. 42, 240–252 (2017).

Weston, C. H. et al. Comparison of preparation design and material thickness on microbial leakage through cavit using a tooth model system. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 105, 530–535 (2008).

Asikainen, S. et al. Specified species in gingival crevicular fluid predict bacterial diversity. PLoS ONE 5, e13589 (2010).

Mortier, E., Gerdolle, D. A., Jacquot, B. & Panighi, M. M. Importance of water sorption and solubility studies for couple bonding agent–resin-based filling material. Oper. Dent. 29, 669–679 (2004).

Newcomb, B. E. Degradation of the sealing properties of a zinc oxide-calcium sulfate-based temporary filling material by entrapped cotton fibers. J. Endod. 27, 789–790 (2001).

Vail, M. M. & Steffel, C. L. Preference of temporary restorations and spacers: A survey of diplomates of the American Board of endodontists. J. Endod. 32, 513–515 (2006).

Alkadi, M. & Alsalleeh, F. Ex vivo microbial leakage analysis of polytetrafluoroethylene tape and cotton pellet as endodontic access cavity spacers. J. Conserv. Dent. 22, 381–386 (2019).

Alkadi, M., Algahtani, F. N., Barakat, R., Almohareb, R. & Alsaqat, R. Assessment of the effect of spacer material on gap and void formation in an endodontic temporary restoration using micro-computed tomography. Sci. Rep. 13, 1–8 (2023).

Olsson, T., Chan, D., Johnson, J. D. & Paranjpe, A. In-vivo microbiologic evaluation of polytetrafluoroethylene and cotton as endodontic spacer materials. Quintessence Int. https://doi.org/10.3290/J.QI.A38679 (2017).

Assalman, A. S. et al. Influence of endodontic cavity design on interfacial voids, class II resin composites sealing ability and tooth fracture resistance: An in vitro study. J. Clin. Med. 13, 6024 (2024).

Yun, S.-M. et al. Coronal microleakage of four temporary restorative materials in class II-type endodontic access preparations. Restor. Dent. Endod. 37, 29–33 (2012).

Shanmugam, S. et al. Coronal bacterial penetration after 7 days in class II endodontic access cavities restored with two temporary restorations: A randomised clinical trial. Aust. Endod. J. 46, 358–364 (2020).

Tosco, V. et al. Micro-computed tomography for assessing the internal and external voids of bulk-fill composite restorations: A technical report. Imaging Sci. Dent. 52, 303–308 (2022).

Rodrigues, D. S. et al. Mechanical strength and wear of dental glass-ionomer and resin composites affected by porosity and chemical composition. J. Bio Tribo Corros. 1, 1–9 (2015).

Sarna-Boś, K., Skic, K., Sobieszczański, J., Boguta, P. & Chałas, R. Contemporary approach to the porosity of dental materials and methods of its measurement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 8903 (2021).

Iranmanesh, P. et al. Application of 3D bioprinters for dental pulp regeneration and tissue engineering (porous architecture). Transp. Porous Media 142, 265–293 (2021).

Roberts, H., Fuentealba, R. & Brewster, J. Microtomographic analysis of resin composite core material porosity. J. Prosthodont. 29, 623–630 (2020).

Elleuch, S., Jrad, H., Wali, M. & Dammak, F. Finite element analysis of the effect of porosity on biomechanical behaviour of functionally graded dental implant. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 55, 99. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544089231197857 (2023).

Gogtay, N. Principles of sample size calculation. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 58, 517 (2010).

de Neves, A. B. et al. Porosity and pore size distribution in high-viscosity and conventional glass ionomer cements: a micro-computed tomography study. Restor. Dent. Endod. 46, e57 (2021).

Wilcox, L. R. & Walton, R. E. The shape and location of mandibular premolar access openings. Int. Endod. J. 20, 223–227 (1987).

Webber, R. T., del Rio, C. E., Brady, J. M. & Segall, R. O. Sealing quality of a temporary filling material. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 46, 123–130 (1978).

Atalay, C. et al. Fracture resistance of endodontically treated teeth restored with bulk fill, bulk fill flowable, fiber-reinforced, and conventional resin composite. Oper. Dent. 41, E131–E140 (2016).

Widerman, F. H., Eames, W. B. & Serene, T. P. The physical and biologic properties of cavit. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 82, 378–382 (1971).

Eliasson, S. T. & Dahl, J. E. Effect of thermal cycling on temperature changes and bond strength in different test specimens. Biomater. Investig. Dent. 7, 16–24 (2020).

Little, P. A. G. et al. Thermal conductivity through various restorative lining materials. J. Dent. 33, 585–591 (2005).

Zdravkov, B. D., Čermák, J. J., Šefara, M. & Janků, J. Pore classification in the characterization of porous materials: A perspective. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 5, 385–395 (2007).

Nagi, S. M., Moharam, L. M. & El Hoshy, A. Z. Fluoride release and recharge of enhanced resin modified glass ionomer at different time intervals. Future Dent. J. 4, 221–224 (2018).

Nicholson, J. & Czarnecka, B. Resin-modified glass-ionomer cements. In Materials for the Direct Restoration of Teeth (eds Nicholson, J. & Czarnecka, B.) 137–159 (Woodhead Publishing, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100491-3.00007-6.

Jamleh, A., Mansour, A., Taqi, D., Moussa, H. & Tamimi, F. Microcomputed tomography assessment of microcracks following temporary filling placement. Clin. Oral Investig. 24, 1387–1393 (2020).

Djouiai, B. & Wolf, T. G. Tooth and temporary filling material fractures caused by Cavit, Cavit W and Coltosol F: An in vitro study. BMC Oral Health 21, 1–8 (2021).

Musanje, L. & Darvell, B. W. Aspects of water sorption from the air, water and artificial saliva in resin composite restorative materials. Dent. Mater. 19, 414–422 (2003).

Øysæd, H. & Ruyter, I. E. Composites for use in posterior teeth: Mechanical properties tested under dry and wet conditions. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 20, 261–271 (1986).

Söderholm, K. J. Degradation of glass filler in experimental composites. J. Dent. Res. 60, 1867–1875 (1981).

Huang, C. et al. Hygroscopic expansion of a compomer and a composite on artificial gap reduction. J. Dent. 30, 11–19 (2002).

Tarasingh, P., Sharada Reddy, J., Suhasini, K. & Hemachandrika, I. Comparative evaluation of antimicrobial efficacy of resin-modified glass ionomers, compomers and giomers—An invitro study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 9, ZC85 (2015).

Gale, M. S. & Darvell, B. W. Thermal cycling procedures for laboratory testing of dental restorations. J. Dent. 27, 89–99 (1999).

Jani, K., Bagda, K., Jani, D. & Patel, P. Effect of storage in water on solubility and effect of thermocycling effect of storage in water on solubility and effect of thermocycling on microhardness of four different temporary restorative materials. NJIRM 6, 76–79 (2015).

Alamin, M. H. et al. Comparative analysis of coronal sealing materials in endodontics: Exploring non-eugenol zinc oxide-based versus glass-ionomer cement systems. Eur. J. Dent. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-0044-1782695/ID/JR2393112-29/BIB (2024).

Cabello Malagón, I. et al. Analysis of the porosity and microhardness of glass ionomer cements. Mater. Sci. 28, 113–119 (2021).

Ghavami-Lahiji, M., Davalloo, R. T., Tajziehchi, G. & Shams, P. Micro-computed tomography in preventive and restorative dental research: A review. Imaging Sci. Dent. 51, 341 (2021).

Kelly, J. R., Benetti, P., Rungruanganunt, P. & Della Bona, A. The slippery slope—Critical perspectives on in vitro research methodologies. Dent. Mater. 28, 41–51 (2012).

Ellis, T. G. & Levy, Y. Research methadology: Review and proposed methods. In Growing Information: Part I (ed. Cohen, E. B.) 323–326 (Informing Science, 2009).

Molnár, J. et al. Fatigue performance of endodontically treated molars restored with different dentin replacement materials. Dent. Mater. 38, e83–e93 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University for supporting this research through sabbatical leave program. The authors want to also thank Meshal M. Al-Sharafa from the research department of Health Science Research Center in Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University for his kind guidance and support in Microcomputed Tomography scanning and imaging, and analysis.

Funding

The authors are grateful for Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University for supporting this research through sabbatical leave program. The funder has no role in designing the experiment or interpreting the findings of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FA: Conceptualization, project administration, methodology, writing original draft, and funding acquisition. MA: Conceptualization, methodology, writing-review and editing.HT & SA: Investigation. LA: Data curationRB: Formal analysis.RH & SE: Methodology. RA: Writing-review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The present study was registered and ethically approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (reference no. 23-0118). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Algahtani, F.N., Alkadi, M., Talic, H.R. et al. Impact of spacers and thermocycling on porosity and gaps in class II endodontic temporary restorations evaluated by microcomputed tomography. Sci Rep 15, 19874 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03458-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03458-x