Abstract

Newcastle disease virus (NDV) is a highly contagious poultry disease that affects the respiratory, nervous, and digestive systems, causing significant losses to the poultry industry. Pyrazole-based scaffolds had significant potential as antiviral agents targeting various pathogens. Thus, a series of 4-substituted pyrazole derivatives were synthesized by reacting 5-chloro-4-formyl-3-methyl-1-phenylpyrazole with some nitrogen and carbon-based nucleophiles. The antiviral efficacy of these compounds was evaluated against NDV by assessing their ability to inhibit virus-induced haemagglutination. Notably, hydrazone 6 and thiazolidinedione derivative 9 achieved complete (100%) protection against NDV with 0% mortality, while the pyrazolopyrimidine derivative 7 provided 95% protection. Additionally, tetrazine 4 and chalcone 11 conferred 85% and 80% protection, respectively. Molecular docking simulation targeting immune receptor TLR4 protein (PDB ID: 3MU3) revealed that compound 6 achieved the highest docking score, surpassing both the reference drug (amantadine) and the co-crystallized ligand (LP4), primarily through hydrophobic interactions with PHE 46 residue. Compound 9 formed two hydrogen bonds with THR 122 and exhibited hydrophobic interaction with TYR 117, whereas compound 7 interacted hydrophobically with THR 122. Pharmacokinetic modeling using the BOILED-Egg model indicated that some compounds are likely to cross the blood-brain barrier (yellow region), while others remain in the white area. Impressively, the compounds also demonstrated desirable drug-likeness profiles. These findings suggest that the synthesized compounds hold promise as potent antiviral candidates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Newcastle disease (ND) is an acute highly contagious viral disease of poultry that affects the respiratory, nervous, and digestive systems, causing significant losses to the poultry industry1. Newcastle disease virus (NDV) is a viral pathogen capable of infecting more than 200 species of wild birds and domestic poultry2. Over the last decade, ND has caused continuous devastating effects on the global poultry industry; therefore, the world organization for animal health (WOAH) listed it as a notifiable terrestrial animal disease, emphasizing its international economic significance3. The incidence of ND has increased because of improper vaccination programs with vaccination failure, the presence of immunosuppressive diseases, and the genetic mutations of the virus, which lead to changes in biological characteristics and pathogenicity, even in vaccinated flocks4.

Poultry flocks encountered by ND are responsible for high rates of economic losses5,6. The disease is characterized by respiratory, neurological, and gastrointestinal symptoms, leading to losses including high mortality rate up to 100% in unvaccinated flocks, a drop in egg production (quantity and quality), weight loss, and growth retardation7. The symptoms of NDV usually appear within two to fifteen days after a bird gets infected, but sometimes it can rise to four weeks. In countries with large poultry industries, outbreaks of NDV resulted in millions of dollars in losses per outbreak. Based on their pathogenicity for chickens, NDV strains are classified into highly pathogenic (velogenic), intermediate (mesogenic), and apathogenic (lentogenic) strains8,9.

The global poultry industry plays a pivotal role in providing eggs and meat for human consumption. However, outbreaks of viral disease, especially NDV, within poultry farms have detrimental effects on various zootechnical parameters, such as body weight gain, feed intake, feed conversion ratio, as well as the quality of egg and meat production. Cases of vaccine failure have been reported in regions where highly pathogenic strains of NDV are prevalent. The disease is well-documented, with 20 genotypes and more than 236 susceptible avian species reported worldwide10,11,12. It spreads when infected birds release the virus through their mouth and rear opening, and other birds can catch it by breathing it in or eating it13. The presentation of NDV symptoms can vary based on the specific virus strain and the species of bird affected.

The ongoing challenge in the development of NDV vaccines lies in the ever-changing nature of genetically varied genotypes that are widely dispersed across different regions14. Understanding the structure and properties of NDV is crucial for developing effective antiviral strategies. Because the number of NDV cases is increasing and viruses are changing upon time, it is crucial to have effective ways of applying new chemicals as antivirals to control and prevent disease2. Commonly, vaccines including live attenuated and inactivated formulations are employed to protect poultry from NDV15. Considerable research efforts have been devoted to the detection of potent antiviral agents16,17,18,19,20.

The viral genome is around 15,200 base pairs (bp) in length and encodes six different proteins: nucleocapsid protein (NP); phosphoprotein (P); matrix protein (M); large RNA polymerase (L); fusion protein (F); and haemagglutinin-neuraminidase (HN). Two other proteins (V and W) could also be coded through P protein mRNA editing21,22. The phylogenetic analysis of F gene sequences of NDVs divided them into two classes (I and II): class I includes avirulent viruses, with a natural reservoir of aquatic wild birds, but one virulent isolate has been included23; whereas class II contains viruses that have higher genetic and virulence variability with 20 genotypes (I–XXI, except the recombinant sequence genotype XV) and are known to infect a wide range of domestic and wild birds21,22,24. NDV genotype VII is a highly pathogenic orthoavulavirus that has caused multiple outbreaks among poultry in Egypt since 2011.

Pyrazole compounds are a significant class of heterocyclic organic compounds imparting distinct chemical properties and biological activities, making pyrazoles a focal point of research in medicinal chemistry, agricultural chemistry, and material sciences25,26,27,28,29,30,31. The pyrazole ring system is a planar structure with considerable electron density around the nitrogen atoms. This configuration allows pyrazoles to engage in various chemical reactions, enabling the synthesis of wide derivatives with tailored properties. Pyrazole derivatives exhibit a wide spectrum of biological properties, making them valuable in the pharmaceutical industry. They are known for their antiviral, antitumor, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and insecticidal properties32,33,34,35,36,37,38.

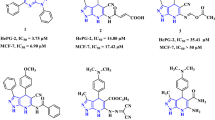

For instance, diverse pyrazole-containing systems exhibited potent antiviral therapeutics against targets like HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), HCV (hepatitis C virus), HSV-1 (Herpes simplex virus), NNRTI (Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors), H1N1 (a swine-origin influenza A), and H5N1 (Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A)16,29,33,39. Recently, antiviral research was primarily focused on the development of nucleoside and nonnucleoside analogues16,40. For example, pyrazole (A) exhibited a high antiviral potency against hepatitis A virus, HCV, and HSV (Fig. 1)40,41. Their unique chemical structure allows for extensive modification, leading to the development of compounds with specific and enhanced properties. Thus, substituted pyrazoles represent important key intermediates for the synthesis of therapeutically active drugs.

Outstanding research into pyrazole derivatives continues to discover new potential uses and benefits, solidifying their importance in science and industry. The design and incorporation of other pharmacophores with a pyrazole in the molecule might lead to innovative potent therapeutic agents. It was also reported that 1,3-diphenylpyrazole derivatives exhibited 95–100% protection of chicks against NDV42. Also, the pyrazole-including agent, BPR1P003443 has potent activity (sub-micromolar) against the influenza virus (cf. Figure 1), which implies an opportunity for developing new effective antiviral agents. In this research and prompted by our strategy44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53, this work attempted to develop new nonnucleoside antiviral agents by synthesizing 4-substituted pyrazole candidates with potential antiviral activity against ND virus in specific pathogen free (SPF) chicken embryos and immune boosting properties of these substances in SPF chicks. supported by molecular docking simulation and modeling pharmacokinetics studies.

Rationale and design

Our rationale and design were based on a structural diversification through conserving the pyrazole core and incorporation of certain side chains or heterocyclic moieties, to attain potential antiviral efficacy. Pyrazole has been described as a crucial scaffold due to its presence in many pharmacologically active compounds. In our search to develop prospective antiviral compounds, insight was drawn from pyrazole’s pharmacophoric features, which have shown antiviral efficacy (cf. Figure 2). To design and produce a new series of 4-substituted pyrazole derivatives, the fundamental pharmacophoric features of pyrazole were kept while heterocyclic and linker side chain moieties were integrated, which are as follows: (i) A pyrazole core (chromophore), which was linked with antiviral activity, was retained in the design, (ii) The linker was modified by incorporating hydrazonyl or α,β-unsaturated carbonyl scaffolds in order to establish more hydrogen bonds during interaction with virus proteins, (iii) To increase the antiviral activity of these candidates, cores of thiophene, tetrazine, pyrazole, thiazolidine, and coumarin were incorporated to the design, which were found to have promising effects in this view. By linking these features, this work intended to produce some 4-substituted pyrazole derivatives with improved antiviral effects (Fig. 2).

Results and discussion

Chemistry

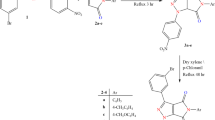

The key aldehyde, 5-chloro-4-formyl-3-methyl-1-phenylpyrazole 154 was allowed to react with various nitrogen and carbon-centered nucleophiles to obtain diverse pyrazole-based candidates (cf. Figures 3 and 4). First, condensation of aldehyde 1 with thiophene-2-carbohydrazide and 2-hydroxybenzohydrazide afforded the corresponding hydrazone candidates 2 and 3, respectively. Absorption bands for NH, C = O, and C = N groups appeared in IR of hydrazone 2, while in hydrazone 3, an extra band for OH group appeared. 1H NMR of hydrazone 2 displayed three characteristic singlet signals as follows: the first is integrated for three protons in the upfield region corresponding to methyl proton, the second is integrated for one proton in the downfield region corresponding to methine proton (CH = N), the third is an exchangeable signal in the downfield corresponding to NH proton.

Hydrazinolysis of hydrazone 2 with hydrazine hydrate in refluxing ethanol produced a mixture of tetrazine 4 and bis-pyrazolylhydrazine 5 derivatives. The 1H NMR of tetrazine derivative 4 displayed two singlet signals corresponding to CH and NH of tetrazine moiety, in addition to a singlet signal of methyl protons. Otherwise, hydrazinolysis of 3 under the same conditions afforded the bis-pyrazolylhydrazine derivative 5. The later compound was confirmed by comparison with an authentic sample prepared from refluxing an ethanolic solution of aldehyde 1 with hydrazine hydrate55.

Noteworthy, treating aldehyde 1 with 4-aminobenzohydrazide in refluxing ethanol under acid catalyzed media achieved the formation of bi-condensation product 6. The IR of 6 lacked NH2 absorption and displayed carbonyl absorption. Further, its 1H NMR disclosed two singlet signals for two methine protons (2 CH = N) in addition to an exchangeable singlet signal for NH proton. In turn, refluxing aldehyde 1 with thiourea under basic conditions produced the heteroannulated product, pyrazolopyrimidine derivative 7 56 (cf. Figure 4). Its 1H NMR showed a singlet signal for a methine proton (CH = N) in the downfield region and an exchangeable singlet signal corresponding to NH proton. The mass spectra of the compounds strongly supported the proposed structures.

On the other hand, treating aldehyde 1 with pyrazole-cyanoacetohydrazone57 in 1,4-dioxane and piperidine at room temperature produced α,β-unsaturated nitrile 8 as yellow crystals. In its IR chart, the absorption band of nitrile functionality appeared at relatively lower value (ν 2206 cm− 1), which was attributed to the conjugation with C = C moiety. Its 1H NMR displayed an exchangeable singlet for NH proton and a singlet signal for C5-H of pyrazolyl moiety. The space models of the isomeric structures of compound 8 confirmed the Z-configuration for the new olefinic double bond, which was probably due to the steric and field effects between the nitrile and pyrazole moieties (cf. Table S1 in S1_file).

Likewise, condensation of aldehyde 1 with 2,4-dioxo-3-phenylthiazolidine in refluxing acetic acid and fused sodium acetate afforded α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compound 9. The space models of the isomeric structures of compound 9 confirmed the E-configuration for the new olefinic double bond, which was probably due to the steric effect of the pyrazole moiety (cf. Table S1).

From the biological and synthetic point of view, chalcones are known to be crucial intermediates in organic synthesis serving as building blocks for many heterocyclic systems with pharmacological importance30,46. Also, based on the biological potential of coumarin and thiophene derivatives58,59,60, chalcone derivatives bearing a moiety of coumarin 10 and thiophene 11 were efficiently synthesized upon treating the aldehyde 1 with 3-acetylcoumarin and 2-acetylthiophene, respectively (cf. Figure 5). The carbonyl of coumarin moiety (in compound 10) appeared in its IR spectrum at ν 1721 cm− 1. Also, in its 1H NMR spectrum, a singlet signal for C4-H of coumarin moiety was displayed at δ 8.59 ppm. Their mass spectra provided the molecular ion peaks besides M + 2 isotopic peaks. The space models of the isomeric structures of chalcones 10 and 11 confirmed the E-configurations for the olefinic double bond, which were probably due to the steric effects of the pyrazole moiety with carbonyl group (cf. Table S1).

Antiviral activity evaluation

Aiming to treat Newcastle disease, many vaccines have been appointed against NDV based on inactivated and attenuated viruses but suited useless due to the genetic changes in the virus. NDV genotype VII is a highly pathogenic Orthoavulavirus that has caused multiple outbreaks among poultry in Egypt since 2011. Haemagglutination is the aggregation of RBCs (red blood cells) in suspension with the presence of certain haemagglutinating virus particles. This phenomenon is a result of the attachment of specific outer viral peplomeres (haemagglutinins) with specific receptors present on the surface of RBCs. This characteristic feature can be used in the detection of viruses. The inhibition of haemagglutination caused by these viruses is the detection of their activity’s inhibition.

Amantadine was selected as the antiviral reference drug due to its well-established mechanism of action as a viral M2 ion channel blocker, primarily used against influenza A virus. Its ability to interfere with viral uncoating and replication makes it a valuable tool for studying early stages of the viral life cycle. Additionally, Amantadine has been reported to exhibit broader antiviral and neuroprotective properties, including modulatory effects on host cellular pathways such as autophagy and ion channel function. These characteristics make it an appropriate reference compound for evaluating antiviral efficacy and potential host-virus interactions in the present study.

Toxicity assays conducted on embryonated chicken SPF eggs revealed that the 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of the tested compounds ranged from 200 to 800 µL per egg (cf. Table 1). The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was determined as the concentration required to completely inhibit viral effects in 50% of the eggs. The selectivity index (SI) for each compound was calculated as a ratio of CC50 to IC5057. The tested compounds demonstrated promising antiviral activity against NDV. When embryonated eggs were inoculated with a mixture of NDV and each compound individually, virus replication was notably impacted. Serial 12-fold dilutions (101 to 1012) of the mixtures were applied, and the allantoic fluid from each group received varying concentrations. The results showed a reduction in virus titer (cf. Table 2).

Bioassay of immune boosting properties of different compounds in SPF chicks

Using amantadine as a reference, the tested compounds were screened for their mortality and protection percentages using day post challenge (DPC) against NDV with vaccinated group (20 chicks). The mortality percentage was calculated from 1st to 6th DPC as (the number of dead birds / total number of birds) × 100. Thus, the protection percent of the vaccine was calculated from 1st to 6th DPC as (the number of live birds / total number of birds) × 100. Also, the protection percent can be calculated as (100 – Mortality). The results revealed that hydrazone 6 and thiazolidinedione derivative 9 exhibited 0% mortality and 100% protection against NDV while pyrazolopyrimidine 7 showed 95% protection (5% mortality). In turn, tetrazine derivative 4 disclosed 85% protection (15% mortality) and chalcone 11 exhibited 80% protection (20% mortality) (Table 3).

Blood samples were collected individually from jugular vein at 28 days post vaccination for potency test by calculation of the HI antibody titer in serum of vaccinated chicks (20 chicks). Haemagglutination inhibition (HI) titer values62 of the tested compounds with respect to amantadine as a standard compound were displayed in Table 4. On the other hand, an immunostimulant is any substance that enhances or stimulates the body’s immune response. Immunostimulants can be natural (like certain bacterial components) or synthetic (like specific drugs or compounds), and they work by activating various components of the immune system.

Comparison of humeral response of the vaccinated group (first group vaccinated only) and other vaccinated groups, which separately received the tested compounds as immunostimulant, revealed that hydrazone 6 has special immune boosting properties as it elevates the antibody titer in the serum of vaccinated chicks. Accordingly, hydrazone and thiazolidinedione derivatives would be considered promising antiviral candidates and can be added to NDV vaccines to raise the treatment percentage and then decrease the mortalities and the economics losses. Also, this prevents disease introduction, reduces susceptibility over time, and facilitates the export of poultry products.

Molecular Docking simulation

A molecular docking approach was applied to offer the possible antiviral mechanism of action through displaying the interaction of a compound with active pockets of the proper target63,64. The immunostimulant property refers to the ability of LPS (lipopolysaccharide) to prompt a strong immune response. LPS is a component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and is recognized by the innate immune system as a pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP). LPS exerts the immunostimulant effect through:

-

(i)

Recognition by Immune Receptors: LPS binds to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on immune cells, specifically in complex with MD-2, a co-receptor that helps in LPS recognition.

-

(ii)

Signal Transduction: Upon binding, this complex initiates a signaling cascade inside the immune cell, leading to the activation of transcription factors such as NF-κB.

-

(iii)

Cytokine Production: This signaling results in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) that help combat infections by recruiting and activating more immune cells.

-

(iv)

Innate Immune Activation: LPS acts rapidly, stimulating the innate immune system, which serves as the first line of defense against pathogens.

Because of this ability to potently activate immune responses, LPS is often used experimentally to mimic infection or to test the immune-stimulating capacity of compounds. However, excessive stimulation by LPS can also lead to hyperinflammation or sepsis, so its effects must be carefully studied. The host immune response against LPS is prompted by myeloid differentiation factor 2 (MD-2) in association with Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on the cell surface65. The MD-2/TLR4-mediated LPS response is regulated by the evolutionarily correlated complex of MD-1 and Toll-like receptor homolog RP105 through a hydrophobic cavity between the two beta-sheets. A lipid-like moiety was observed inside the cavity, proposing the possibility of a direct MD-1/LPS interaction.

In molecular docking or drug design studies, compounds interacting with TLR4 or LPS-binding pathways are evaluated for their potential immunomodulatory or antiviral effects by influencing these immune activation pathways. The immune receptor TLR4 was chosen for molecular docking due to its critical role in innate immunity and its ability to recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns including LPS. As a key receptor in mediating inflammatory responses, TLR4 activation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of various infections. Targeting TLR4 through docking studies allows the exploration of potential interactions that may modulate it signaling pathway, offering insight into therapeutic strategies aimed at controlling excessive immune dysregulation.

Thus, molecular docking analysis of the promising pyrazole-based compounds 6, 7, and 9 was investigated against target immune receptor TLR4 (PDB ID: 3MU3) active sites, aiming to account for LPS-induced responses. The binding affinity was measured by the binding energy (S-score, kcal/mol) and hydrogen bonds. For better understanding, the reference drug (amantadine) was also docked into the TLR4 active pockets. All complexes were docked in the same groove of binding pocket of the native co-crystallized ligand (LP4) (Tables 5 and 6). Table 6 displays the amino acids involved in binding interactions between compounds and active sites of protein including hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions. Also, Table 6 offers 2D and 3D representation interactions of the promising compounds with the target TLR4 enzyme.

The docking results showed that the amino acid residues PHE 46, THR 122, and TYR 117 were implicated in receptor binding through hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions. Herein, the key amino acid THR 122 was common in the interactions with the reference (amantadine) and co-crystallized ligands (LP4) as depicted in Table 5. Thus, compound 6 exhibited the best docking score (-7.2322 kcal/mol) compared to amantadine (-4.1456 kcal/mol) and co-crystallized ligand (-9.7099 kcal/mol). The interaction of 6 with target TLR4 was through hydrophobic interaction with PHE 46 amino acid. Next, compound 9 exhibited binding energy of -6.1678 kcal/mol through two hydrogen bonding with the key amino acid THR 122 and hydrophobic interaction with TYR 117. Otherwise, compound 7 showed hydrophobic interaction with THR 122.

Modeling pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetics properties of the prepared candidates 1–11 were assessed utilizing the SwissADME free web tool compared to the reference, Amantadine (cf. Figures S1-S11 in S1_file and Table S2 in S3_file). A thorough analysis of ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) profiles and key physicochemical properties of compounds in addition to their drug-likeness evaluations offered a comprehensive recognizing of their pharmacological properties66,67. ADME analysis is also worthy insights into the biological behavior of compounds. All compounds are assessed as non-inhibitors of CYP2D6, and hence side effects (i.e., liver dysfunction) are not anticipated upon their administration. Recognizing the absorption properties, compounds 2, 3, 4, 8, and 9 uncovered gastrointestinal tract (GIT) absorption upon its being in the BOILED-Egg white area chart as shown in Fig. 6. Whilst compounds 1, 7, 10, and 11 were presented in the chart yellow area and predicted to penetrate the blood-brain barrier. They are not potential substances for permeability glycoprotein (PGP), indicated by red. Thus, these compounds revealed desirable drug-likeness.

The pharmacokinetics and antiviral assessment of the examined compounds, compared to Amantadine, showed crucial factors affecting their potential activity. These key factors include TPSA (topological polar surface area), lipophilicity (Consensus Log Po/w), and GI (gastrointestinal) absorption, which affect their bioavailability at the target place. The comparison of these key factors and antiviral SI values of the examined compounds was depicted in Table 7. Typically, lower TPSA values are associated with better membrane permeability, enhancing compound’s antiviral activity. Compared to Amantadine, all compounds exhibited favorite TPSA values (< 140 Å2. The slightly higher TPSA values of some compounds than Amantadine suggested other factors like lipophilicity or specific interactions with receptors, may reinforce any potential decrease in permeability. Also, all compounds showed Consensus Log Po/w values higher than Amantadine. For example, compound 6 exhibited TPSA value of 89.46 Å2 and low GI absorption but it had the highest Consensus Log Po/w value (5.64), improving its lipophilic interactions and antiviral activity.

Conclusion

A series of pyrazole-based candidates was prepared upon treatment of 5-chloro-4-formyl-3-methyl-1-phenylpyrazole with certain nitrogen and carbon-centered nucleophiles. The antiviral activity of the prepared compounds was examined against NDV, which revealed that hydrazone 6 and thiazolidinedione derivative 9 exhibited 0% mortality and 100% protection against NDV while pyrazolopyrimidine derivative 7 displayed 95% protection. In turn, tetrazine derivative 4 showed 85% and chalcone 11 exhibited 80% protection. These results were supported by molecular docking simulation with TLR4 enzyme. The docking results showed that compound 6 exhibited the best docking score (-7.2322 kcal/mol) compared to the reference agent, amantadine (-8.1456 kcal/mol) and co-crystallized ligand, LP4 (-9.7099 kcal/mol), through hydrophobic interaction with PHE 46 amino acid. While compound 9 exhibited binding energy of -6.1678 kcal/mol through two hydrogen bonding with THR 122 and hydrophobic interaction with TYR 117. Otherwise, compound 7 showed hydrophobic interaction with THR 122. Regarding modeling pharmacokinetics, all compounds exhibited favorite TPSA values and compounds 1, 7, 10, and 11 were presented in the BOILED-Egg chart yellow area and predicted to penetrate the blood-brain barrier, exhibiting desirable drug-likeness and oral bioavailability properties. Thus, hydrazone and thiazolidinedione derivatives would be considered promising antiviral candidates and can be added to NDV vaccines to raise the treatment percent and then decrease the mortality percent and the economics losses.

Materials and methods

Melting points were measured in open capillary tubes on a MEL-TEMP II electrothermal melting point apparatus. The elemental analyses were performed on a Perkin-Elmer 2400 CHN elemental analyzer (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA) at Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University. Infrared spectra (ν, cm−1) were recorded utilizing KBr wafer technique on Fourier Transform Infrared Thermo Electron Nicolet iS10 Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. Waltham, MA) at Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University. Electron impact mass spectra (EIMS) were run on direct probe controller inlet part to single quadrupole mass analyzer in Thermo Scientific GC-MS MODEL (ISQ LT) using Thermo X-CALIBUR software at regional center for mycology and biotechnology (RCMB), Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt. 1H NMR spectra (δ, ppm) were recorded on BRUKER 400 MHz Spectrometer at Faculty of Pharmacy, Ain Shams University, with tetramethyl silane as an internal standard, using DMSO-d6 as a solvent (Figures S12-S50). Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was run utilizing TLC aluminum sheets silica gel 60 F254 (Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ).

N’-((5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)thiophene-2-carbohydrazide (2)

A solution of aldehyde 1 54 (0.01 mol) and thiophene-2-carbohydrazide (0.01 mol) in absolute ethyl alcohol (25 mL) and glacial acetic acid (0.2 mL) was refluxed for 4 h. The formed precipitate was filtered and recrystallized from ethyl alcohol to produce yellow crystals; mp. 178–180 oC; yield 91%. IR (KBr, ν, cm−1): 3274 (NH), 3075, 3063 (CH aromatic), 2929 (CH aliphatic), 1657 (C = O), 1608 (C = N). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 2.50 (s, 3 H, CH3), 7.22 (t, 1 H, CH, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.52–7.62 (m, 5 H, Ar-H), 7.89 (d, 1 H, CH, J = 7.8 Hz), 8.13 (d, 1 H. CH, J = 8.4 Hz), 8.45 (s, 1 H, CH = N), 11.81 (br.s, 1 H, NH). EIMS (70 eV, m/z, %): 346.40 (M + 2, 5), 344.36 (M+., 17), 340.39 (73), 313.47 (47), 262.22 (100), 248.32 (68), 234.45 (63), 100.27 (49), 77.22 (74), 56.17 (61). Anal. Calcd for C16H13ClN4OS (344.82): C, 55.73; H, 3.80; N, 16.25; Found: C, 55.60; H, 3.74; N, 16.27%.

N’-((5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)-2-hydroxybenzohydrazide (3)

A solution of aldehyde 1 (0.01 mol) and 2-hydroxybenzohydrazide (0.01 mol) in absolute ethyl alcohol (25 mL) and glacial acetic acid (0.2 mL) was refluxed for 4 h. The formed precipitate was filtered and recrystallized from ethyl alcohol to give yellow crystals; mp. 198–200 oC; yield 78%. IR (KBr, ν, cm−1): 3350 (br. OH), 3209 (NH), 3073 (CH aromatic), 2926 (CH aliphatic), 1638 (C = O), 1605 (C = N). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 2.51 (s, 3 H, CH3), 6.97 (d, 1 H, Ar-H, J = 7.4 Hz), 7.44–7.61 (m, 7 H, Ar-H), 7.89 (d, 1 H, Ar-H, J = 7.2 Hz), 8.49 (s, 1 H, CH = N), 11.83 (br.s, 1 H, NH), 11.97 (br.s, 1 H, OH). EIMS (70 eV, m/z, %): 356.13 (M + 2, 4), 354.15 (M+., 14), 351.24 (33), 348.46 (38), 305.11 (41), 283.89 (79), 272.68 (42), 269.42 (100), 160.23 (53), 111.51 (39), 78.79 (37), 69.08 (35). Anal. Calcd for C18H15ClN4O2 (354.79): C, 60.94; H, 4.26; N, 15.79; Found: C, 60.82; H, 4.20; N, 15.80%.

Hydrazinolysis of hydrazone 2

A mixture of hydrazone 2 (0.01 mol) and hydrazine hydrate (0.015 mol, 80%) in absolute ethyl alcohol (25 mL) was refluxed for 4 h. The formed precipitate while heating was filtered and recrystallized from ethyl alcohol to afford 1,2-bis((5-chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1 H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)hydrazine (5) as beige crystals, mp. 249–251 °C [Lit55 mp, 250–252 oC] (Identity: mp., mixed mp., TLC, and IR). The mother liquor was concentrated and then left to stand at room temperature. The precipitated solid was filtered and recrystallized from petroleum ether (60–80) to give tetrazine derivative 4.

6-(5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-3-(thiophen-2-yl)-1,6-dihydro-1,2,4,5-tetrazine (4)

Yellow crystals; mp. 200–202 °C; yield 38%. IR (KBr, ν, cm− 1): 3177 (NH), 3062, 3027 (CH aromatic), 2955, 2922 (CH aliphatic), 1625 (C = N). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 2.51 (s, 3 H, CH3), 4.26 (s, 1 H, CH), 7.14 (t, 1 H, Ar-H, J = 7.2 Hz), 7.26 (m, 1 H, Ar-H), 7.53–7.74 (m, 6 H, Ar-H), 8.59 (br.s, 1 H, NH). EIMS (70 eV, m/z, %): 358.02 (M + 2, 12), 356.07 (M+., 38), 341.21 (49), 306.33 (37), 283.93 (100), 228.17 (41), 200.33 (31), 132.35 (21), 98.13 (17), 95.51 (35), 83.23 (51). Anal. Calcd for C16H13ClN6S (356.83): C, 53.86; H, 3.67; N, 23.55; Found: C, 53.72; H, 3.59; N, 23.58%.

(E/Z)-N’-((5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)-4-(((5-chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1 H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)amino)benzohydrazide (6)

A solution of aldehyde 1 (0.01 mol) and 4-aminobenzohydrazide (0.01 mol) in absolute ethyl alcohol (25 mL) and glacial acetic acid (0.2 mL) was refluxed for 4 h. The formed precipitate was filtered and recrystallized from ethanol to give yellow crystals; mp. 226–228 °C; yield 77%. IR (KBr, ν, cm−1): 3210 (NH), 3059 (CH aromatic), 2970 (CH aliphatic), 1669 (C = O). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 2.32 (s, 6 H, 2 CH3), 7.40–8.02 (m, 14 H, Ar-H), 8.49 (s, 1 H, CH = N-NH), 8.67 (s, 1 H, CH = N), 11.78 (br.s, 1 H, NH). EIMS (70 eV, m/z, %): 560.21 (M + 4, 15), 558.34 (M + 2, 7), 556.78 (M+., 22), 467.06 (39), 451.01 (63), 445.21 (36), 443.11 (43), 422.97 (57), 419.14 (95), 408.18 (43), 385.84 (55), 344.15 (57), 211.16 (100), 121.13 (88), 58.93 (75). Anal. Calcd for C29H23Cl2N7O (556.45): C, 62.60; H, 4.17; N, 17.62; Found: C, 62.51; H, 4.11; N, 17.65%.

3-Methyl-1-phenyl-1,7-dihydro-6H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine-6-thione (7)

A solution of aldehyde 1 (0.01 mol) and thiourea (0.01 mol) in alcoholic sodium hydroxide (20 mL, 20%) was refluxed for 8 h. The reaction mixture was allowed to stand at room temperature and then poured onto ice/water and acidified with diluted hydrochloric acid (10%). The solid obtained was filtered, washed with water, dried, and recrystallized from ethanol to give yellow crystals; mp. 181–183 °C [Lit56 mp. 182–184 °C]; yield 65%. IR (KBr, ν, cm− 1): 3361 (NH), 3073 (CH aromatic), 2924 (CH aliphatic), 1629 (C = N), 1262 (C = S). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 2.34 (s, 3 H, CH3), 7.29 (t, 1 H, Ar-H, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.45–7.87 (m, 2 H, Ar-H), 8.11 (d, 2 H, Ar-H, J = 7.4 Hz), 9.57 (s, 1 H, CH pyrimidine), 13.8 (br.s, 1 H, NH). EIMS (70 eV, m/z, %): 242.45 (M+., 7), 222.75 (72), 220.54 (62), 202.05 (49.6), 193.99 (43), 181.67 (54), 176.06 (94), 144.99 (66), 137.08 (59), 131.56 (41), 108.14 (46), 104.17 (73), 101.7 (100), 83.67 (49), 77.99 (57). Anal. Calcd. for C12H10N4S (242.30): C, 59.48; H, 4.16; N, 23.12; Found: C, 59.40; H, 4.12; N, 23.14%.

3-(5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-2-cyano-N’-((1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)acrylohydrazide (8)

A solution of aldehyde 1 (0.01 mol) with 2-cyano-N’-((1,3-diphenylpyrazol-4-yl)methylene)-acetohydrazide57 (0.01 mol) in 1,4-dioxane and piperidine (0.1 mL) was stirred for 8 h at room temperature. The solid product was formed, filtered, and recrystallized from 1,4-dioxane to give yellow crystals; mp. 188–191 °C; yield 63%. IR (KBr, ν, cm− 1): 3242 (NH), 3052 (CH aromatic), 2930 (CH aliphatic), 2206 (C ≡ N), 1678 (C = O), 1614 (C = N). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 2.51 (s, 3 H, CH3), 7.18–8.14 (m, 15 H, Ar-H), 8.39 (s, 1 H, CH=), 8.69 (s, 1 H, C5-H pyrazole), 9.21 (s, 1 H, CH = N), 11.68 (br.s, 1 H, NH). EIMS (70 eV, m/z, %): 534.08 (M + 2, 4), 532.01 (M+., 13), 505.10 (48), 493.67 (37), 422.44 (47), 413.57 (31), 410.3 (52), 366.44 (32), 354.53 (43), 269.06 (50), 219.84 (37), 208.5 (38), 180.93 (37), 138.34 (49), 112.08 (35), 85.21 (100). Anal. Calcd for C30H22ClN7O (532.00): C, 67.73; H, 4.17; N, 18.43; Found: C, 67.60; H, 4.10; N, 18.46%.

5-((5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylene)-3-phenylthiazolidine-2,4-dione (9)

A mixture of aldehyde 1 (0.01 mol) and 3-phenylthiazolidine-2,4-dione (0.01 mol) in glacial acetic acid and anhydrous sodium acetate (0.01 mol) was refluxed for 10 h. The formed precipitate was filtered and recrystallized from ethanol to give brown crystals; mp. 160–162 °C; yield 58%. IR (KBr, ν, cm− 1): 3140, 3062 (CH aromatic), 2987, 2854 (CH aliphatic), 1720, 1677 (C = O vibrational coupling). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 2.45 (s, 3 H, CH3), 7.54–7.62 (m, 10 H, Ar-H), 9.91 (s, 1 H, CH=). EIMS (70 eV, m/z, %): 397.31 (M + 2, 4), 395.45 (M+., 11), 378.32 (20), 377.23 (22), 336.23 (48), 159.13 (30), 157.55 (22), 131.29 (21), 93.07 (100), 92.16 (27), 78.05 (32), 77.15 (55), 76.29 (21), 66.13 (33), 65.26 (25), 63.29 (21). Anal. Calcd. for C20H14ClN3O2S (395.86): C, 60.68; H, 3.56; N, 10.62; Found: C, 60.57; H, 3.49; N, 10.59%.

3-(3-(5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)acryloyl)-2H-chromen-2-one (10)

A mixture of aldehyde 1 (0.01 mol) and 3-acetylchromen-2-one (0.01 mol) in absolute ethanol (20 mL) containing piperidine (0.1 mL) was refluxed for 3 h. The formed precipitate was filtered and recrystallized from butanol to get yellow crystals; mp. 260–262 oC; yield 43%. IR (KBr, ν, cm− 1): 3064 (CH aromatic), 2977, 2958 (CH aliphatic), 1721 (C = O coumarin), 1656 (C = O ketone). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 2.54 (s, 3 H, CH3), 7.45–7.62 (m, 11 H, Ar-H + CH = CH), 8.59 (s, 1 H, C4-H coumarin). EIMS (70 eV, m/z, %): 392.80 (M + 2, 8), 390.41 (M+., 24), 367.45 (55), 313.13 (28), 252.17 (33), 227.21 (35), 185.10 (45), 157.83 (34), 123.40 (81), 107.05 (64), 97.85 (100), 95.08 (98). Anal. Calcd for C22H15ClN2O3 (390.82): C, 67.61; H, 3.87; N, 7.17; Found: C, 67.53; H, 3.80; N, 7.20%.

3-(5-Chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-1-(thiophen-2-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (11)

A mixture of aldehyde 1 (0.01 mol) and 2-acetylthiophene (0.01 mol) in ethanolic sodium hydroxide (10 mL, 20%) was stirred for 3 h at an ambient temperature. The formed precipitate was filtered and recrystallized from ethyl alcohol to furnish yellow crystals, mp. > 300 °C, yield 56%. IR (KBr, ν, cm−1): 3065 (CH aromatic), 2983, 2922 (CH aliphatic), 1649 (C = O). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ (ppm): 2.53 (s, 3 H, CH3), 7.32 (t, 1 H, CH, J = 7.4 Hz), 7.50–7.56 (m, 2 H, Ar-H), 7.59–7.63 (m, 5 H, Ar-H), 8.08 (d, 1 H, CH=, J = 6.5 Hz), 8.17 (d, 1 H. CH=, J = 6.5 Hz). EIMS (70 eV, m/z, %): 330.20 (M + 2, 20), 328.48 (M+., 51), 296.54 (30), 242.35 (45), 205.51 (100), 195.02 (48), 88.99 (58), 85.48 (73). Anal. Calcd for C17H13ClN2OS (328.81): C, 62.10; H, 3.99; N, 8.52; Found: C, 62.01; H, 3.93; N, 8.54%.

Antiviral activity

Materials

NDV Genotype 7D antigen accession No. KM288609 of 1010 EID50/mL was obtained from Central Laboratory for Evaluation of veterinary Biologics (CLEVB), Cairo, Egypt. Eight compounds were checked (2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 11). Embryonated SPF chicken eggs (ECES) one day old SPF come from the National Project for production of SPF eggs, Kom Oshim, Fayoum, Egypt. It was kept in the egg incubator at 37 °C with humidity 60–80% till the age of 9–11 days old. Freshly collected chicken erythrocytes (1 and 10%) were prepared in saline solution after several washes in HA assay.

Methods

Cytotoxicity

Groups of nine days SPF embryonated chicken eggs were inoculated with different concentrations of each tested compound for the calculation of cytotoxicity concentration 50% (CC50). Uninoculated SPF eggs were always included as control of embryo. The eggs were inoculated via allantoic cavity and were incubated for six days post inoculation at 37 °C with humidity 70%. CC50 of each test compound was determined as the concentration of compound that induced any embryos mortalities or any deviation than normal control embryos in 50% of embryonated chicken eggs.

Inhibition concentration

Other groups of SPF embryonated chicken eggs were inoculated with a mixture of minimal cytotoxic concentration of different tested compounds with 1010 EID50/mL of NDV (0.2 mL per egg) for calculation of the antiviral inhibitory concentration 50% (IC50). Uninoculated SPF eggs were always included as control of embryo. The eggs were inoculated via allantoic cavity and were incubated for six days PI at 37 °C with humidity 70%. IC50 of tested compounds was assayed as the concentration of the compound that fully inhibited virus effect in 50% of embryonated chicken eggs.

CC50/IC50 assay

Pharmaceutical safety is an essential factor in the development of every medicament. It is essential to establish that an investigational product has antiviral activity at concentrations that can be achieved in vivo without inducing toxic effects to cells. Furthermore, in a cell culture model, the apparent antiviral activity of an investigational product can be the result of host cell death after exposure to the product. Thus, it is crucial to determine the cytotoxic potential of the formulation on the cell line used in the antiviral assays.

CC50 is the concentration of test compounds required to reduce cell viability by 50%. The cytotoxicity of the test compounds is best determined concurrently with uninfected cells to obtain CC50 values. Cytotoxicity tests use a series of increasing concentrations of the antiviral product to determine what concentration results in the death of 50% of the host cells. This value is the median cellular cytotoxicity concentration and is identified by CC50.

We recommend determining CC50 values in both stationary and dividing cells from multiple relevant human cell types and tissues to ascertain the potential for cell-cycle, species, or tissue-specific toxicities. In-vitro susceptibility of viruses to antiviral agents is typically measured as IC50, which is the concentration of antiviral that lowers 50% of the virus-induced cytopathic effect (CPE) and the number of plaques formed. The relative effectiveness of the investigational product in inhibiting viral replication compared to inducing cell death is defined as the therapeutic or selectivity index.

Selectivity index (SI)

SI of the tested compound was expressed as CC50/IC50 was calculated using the method described61.

Antiviral assay

Screening of antiviral activity of different compounds was performed using their non-cytotoxic concentration. Therefore, the investigation of different compounds as inhibitory agents against NDV replication (12-fold serial dilutions were performed) in SPF chicken embryos and their cytotoxicity was recorded. Nontoxic concentrations of tested compounds (lower than CC50) were checked for antiviral properties against NDV replication in SPF chicken embryos as follows:

(1) Mixing 0.2 mL of the NDV and 0.2 mL of each compound separately and incubation for 1 h at an ambient temperature.

(2) 12-fold serial dilutions of the mixtures were prepared.

(3) Eight groups (480 eggs) of 9 days old SPF were inoculated by varying serial dilutions (from 1st dilution to 12th dilution, each dilution in five eggs) of each mixture (0.2 mL per egg) were inoculated via allantoic route.

(4) Daily examination of the inoculated eggs, deaths through 24 h post inoculation (PI) were discarded, and mortality between 2nd day and 6th day recognized as specific death.

(5) The NDV infectivity in ECE was determined by haemagglutinating activity of the allantoic fluid of the inoculating eggs as measured by the micro technique of the haemagglutinating (HA) test62.

(6) Virus titer was calculated using method62 and comparison of the known NDV titer with the antiviral activity.

Immune response of different compounds in SPF chicks

Evaluation of immune boosting properties of different compounds (4, 6, 7, 9, and 11) was examined in one day old SPF chicks. A total of 160 SPF chicks were divided into eight groups each contains 20 chicks (each group isolated in biosafety isolator). At seven days old, samples from each group were assessed for ND antibodies by HI test to detect maternal antibodies. All chicks were proved to be free from ND antibodies by HI test.

First group (vaccinated NDV ‘Lasota’ only): consist of 20 experimental chicks were vaccinated with inactivated NDV vaccine. The vaccine was injected with 0.5 mL/bird subcutaneously in the dorsal region of the neck, each group consists of 20 chicks were vaccinated with inactivated NDV vaccine. Six milliliters from diluted nontoxic concentration of each tested compound (4, 6, 7, 9, and 11), respectively (each group separated in biosafety isolator) was added to the drinking water for five groups and another three groups every day for 28 day post vaccination. Eighth group (20 chicks) was kept in separate isolator as non-vaccinated negative control.

Blood samples were collected separately from groups from jugular vein for estimation of the HI antibody titer in serum of vaccinated chicks at 28-day post vaccination by HA inhibition technique described68 using standard ND antigen (for HA) with the comparison of humeral response of vaccinated group and other vaccinated groups mixed with the tested compound as immunostimulant. After collection of blood samples vaccinated groups and control group were challenged with a local isolated strain of NDV (Genotype 7D NDV antigen accession No. KM288609) containing at least 1010 EID50/bird69.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Alexander, D. J., Aldous, E. W. & Fuller, C. M. The long view: a selective review of 40 years of Newcastle disease research. Avian Pathol. 41, 329–335 (2012).

Miller, P. & Koch, G. Newcastle disease, other avian paramyxoviruses and avian metapneumovirus infections (Chap. 3). Dis. Poult. 112, 29 (2020).

Afonso, C. L., Miller, P. J., Roth, J. A. & Richt Newcastle Disease: Progress and Gaps in the Development of Vaccines and Diagnostic Tools, Vaccines and Diagnostics for Transboundary Animal Diseases: International Symposium, Ames, Iowa, September 2012: Proceedings,J.A. I.A. Morozov (2013).

Elfatah, K. S. A. et al. Molecular characterization of velogenic Newcastle disease virus (Sub-genotype VII.1.1) from wild birds, with assessment of its pathogenicity in susceptible chickens. Animals 11, 505 (2021).

Siddique, A. B., Rahman, S. U., Hussain, I. & Muhammad, G. Frequency distribution of opportunistic avian pathogens in respiratory distress cases of poultry. Pak Vet. J. 32, 386 (2012).

Cheema, B. F., Siddique, M., Sharif, A., Mansoor, M. K. & Iqbal, Z. Sero-Prevalence of avian influenza in broiler flocks in district Gujranwala (Pakistan). Internat J. Agri Boil. 13, 850 (2011).

Ratih, D., Handharyani, E. & Setiyaningsih, S. Pathology and immunohistochemistry study of Newcastle disease field case in chicken in Indonesia. Vet. World. 10, 1066 (2017).

Aamir, S., Tanveer, A., Muhammad, U., Abdul, R. & Zahid, H. Prevention and control of Newcastle disease. Internat J. Agri Innov. Res. 3, 2319 (2014).

Miller, P. J. Newcastle disease in poultry (Avian pneumoencephalitis, exotic or velogenic Newcastle disease). Veterinary Manual. 11th edn., United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, USA, 50–56. (2016).

Czifra, G., Meszaros, J., Horvath, E., Moving, V. & Engström, B. Detection of NDV-specific antibodies and the level of protection provided by a single vaccination in young chickens. Avian Pathol. 27, 562–565 (1998).

Dewidar, A. A., El-Sawah, A., Shany, S. A., Dahshan, A. H. M. & Ali, A. Genetic characterization of genotype VII. 1.1 Newcastle disease viruses from commercial and backyard broiler chickens in Egypt. Ger. J. Vet. Res. 1, 11–17 (2021).

Dimitrov, K. M., Afonso, C. L., Yu, Q. & Miller, P. J. Newcastle disease vaccines-A solved problem or a continuous challenge? Vet. Microbiol. 206, 126–136 (2017).

Dimitrov, K. M. et al. Newcastle disease viruses causing recent outbreaks worldwide show unexpectedly high genetic similarity to historical virulent isolates from the 1940s. J. Clin. Microbiol. 54, 1228–1235 (2016).

Ravikumar, R., Chan, J. & Prabakaran, M. Vaccines against major poultry viral diseases: strategies to improve the breadth and protective efficacy. Viruses 14, 1195 (2022).

Senne, D. & King, D. Kapczynski°, by vaccination. Dev. Biol. Basel. 119, 165–170 (2004).

Hashem, A. I., Youssef, A. S. A., Kandeel, K. A. & Abou-Elmagd, W. S. I. Conversion of some 2(3H)-furanones bearing a Pyrazolyl group into other heterocyclic systems with a study of their antiviral activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 42, 934–939 (2007).

Morsy, A. R. et al. Antiviral activity of pyrazole derivatives bearing a hydroxyquinoline scaffold against SARS-CoV-2, HCoV-229E, MERS-CoV, and IBV propagation. RSC Adv. 14(38), 27935–27947 (2024).

Watanabe, K., Rahmasari, R., Matsunaga, A., Haruyama, T. & Kobayashia, N. Anti-influenza viral effects of honey in vitro: potent high activity of Manuka honey. Arch. Med. Res. 45, 359 (2014).

Riyadh, S. M., Farghaly, T. A., Abdallah, M. A. & Abdalla, M. M. Abd El-Aziz. New pyrazoles incorporating pyrazolylpyrazole moiety: synthesis, anti-HCV and antitumor activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 45(3), 1042 (2010).

Abou-Elmagd, W. S. I., Nassif, S. A., Morsy, A. R., El-Kousy, S. M. & Hashem, A. I. Synthesis and anti H5N1 activities of some Pyrazolyl substituted N-heterocycles. Nat. Sci. 14(9), 115 (2016).

Diel, D. G. et al. Genetic diversity of avian paramyxovirus type 1: proposal for a unified nomenclature and classification system of Newcastle disease virus genotypes. Infect. Genet. Evol. 12, 1770–1779 (2012).

Dimitrov, K. M. et al. Updated unified phylogenetic classification system and revised nomenclature for Newcastle disease virus. Infect. Genet. Evol. 74, 103917 (2019).

Liu, X. et al. Surveillance for avirulent Newcastle disease viruses in domestic ducks (Anas Platyrhynchos and Cairina moschata) at live bird markets in Eastern China and characterization of the viruses isolated. Avian Pathol. 38, 377–391 (2009).

Snoeck, C. J. et al. Muller C.P. High genetic diversity of Newcastle disease virus in poultry in West and central Africa: cocirculation of genotype XIV and newly defined genotypes XVII and XVIII. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51, 2250–2260 (2013).

Abdelhamid, A. O. et al. Utility of 5–(furan–2-yl)–3–(p–tolyl)–4,5–dihydro–1H–pyrazole–1–carbothioamide in the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds with antimicrobial activity. BMC Chem. 13, 48 (2019).

Rashad, A. E., Hegab, M. I., Abdel-Megeid, R. E., Micky, J. A. & Abdel-Megeid, F. M. Synthesis and antiviral evaluation of some new pyrazole and fused pyrazolopyrimidine derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 16, 7102–7106 (2008).

El-Helw, E. A. E., Alzahrani, A. Y. & Ramadan, S. K. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of thiophene-based heterocycles derived from thiophene-2-carbohydrazide. Future Med. Chem. 16(5), 439–451 (2024).

Youssef, Y. M. et al. Synthesis and antioxidant, antimicrobial, and antiviral activity of some pyrazole-based heterocycles using a 2(3H)-furanone derivative. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 20(9), 2203–2216 (2023).

Ramadan, S. K. & Abou-Elmagd, W. S. I. Synthesis and anti H5N1 activities of some novel fused heterocycles bearing Pyrazolyl moiety. Synth. Commun. 48(18), 2409–2419 (2018).

Kaddah, M. M., Fahmi, A. A., Kamel, M. M., Ramadan, S. K. & Rizk, S. A. Synthesis, characterization, computational chemical studies and antiproliferative activity of some heterocyclic systems derived from 3-(3-(1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)acryloyl)-2H-chromen-2-one. Synth. Commun. 51(12), 1798–1813 (2021).

Ghareeb, E. A., Mahmoud, N. F. H., El-Bordany, E. A. & El-Helw, E. A. E. Synthesis, DFT, and eco-friendly insecticidal activity of some N-heterocycles derived from 4-((2-oxo-1,2-dihydroquinolin-3-yl)methylene)-2-phenyloxazol-5(4H)-one. Bioorg. Chem. 112, 104945 (2021).

El-Helw, E. A. E., Hosni, E. M., Kamal, M., Hashem, A. I. & Ramadan, S. K. Synthesis, insecticidal activity, and molecular Docking analysis of some benzo[h]quinoline derivatives against Culex pipiens L. Larvae. Bioorg. Chem. 150, 107591 (2024).

Dawood, K. M., Abdel-Gawad, H., Mohamed, H. A. & Badria, F. A. Synthesis, anti-HSV-1, and cytotoxic activities of some new pyrazole-and isoxazole-based heterocycles. Med. Chem. Res. 20, 912–919 (2011).

El-Helw, E. A., Derbala, H. A., El-Shahawi, M. M., Salem, M. S. & Ali, M. M. Synthesis and in vitro antitumor activity of novel Chromenones bearing benzothiazole moiety. Russ J. Bioorg. Chem. 45, 42–53 (2019).

Elsayed, G. A., Mahmoud, N. F. H. & Rizk, S. A. Solvent free synthesis and antimicrobial properties of some novel furanone and spiropyrimidone derivatives. Curr. Org. Synth. 15, 413 (2018).

Kaddah, M. M., Fahmi, A. A., Kamel, M. M., Rizk, S. A. & Ramadan, S. K. Rodenticidal activity of some Quinoline-Based heterocycles derived from Hydrazide-Hydrazone derivative. Polycycl. Aromat. Compds. 43(5), 4231–4241 (2023).

Abdelrahman, A. M., Fahmi, A. A., Rizk, S. A. & El-Helw, E. A. E. Synthesis, DFT and antitumor activity screening of some new heterocycles derived from 2,2’-(2-(1,3-Diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)ethene-1,1-diyl)bis(4H-benzo[d][1,3]oxazin-4-one). Polycycl. Aromat. Compds. 43(1), 721–739 (2023).

El-Helw, E. A. E. et al. Synthesis and in Silico studies of certain benzo[f]quinoline-based heterocycles as antitumor agents. Sci. Rep. 14, 15522 (2024).

Ouyang, G. et al. Synthesis and antiviral activity of novel pyrazole derivatives containing oxime esters group. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 16, 9699–9707 (2008).

Zeng, L. et al. Efficient synthesis and utilization of phenyl-substituted heteroaromatic carboxylic acids as Aryl diketo acid isosteres in the design of novel HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 18, 4521–4524 (2008).

Ding, Y. et al. Synthesis of thiazolone-based sulfonamides as inhibitors of HCV NS5B polymerase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 17, 2665 (2007).

Morsy, A. R., Ramadan, S. K. & Elsafty, M. M. Synthesis and antiviral activity of some pyrrolonyl substituted heterocycles as additives to enhance inactivated Newcastle disease vaccine. Med. Chem. Res. 29, 979–988 (2020).

Shih, S. R. et al. Pyrazole compound BPR1P0034 with potent and selective anti-influenza virus activity. J. Biomed. Sci. 17, 13 (2010).

Mahmoud, N. F. H., El-Bordany, E. A. & Elsayed, G. A. Synthesis and Pharmacological activities of Pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidine and Pyrano[2,3‐d]pyrimidine‐5‐one derivatives as new fused heterocyclic systems. J. Chem. 2017(1), 5373049 (2017).

Kaddah, M. M. et al. Synthesis and biological activity on IBD virus of diverse heterocyclic systems derived from 2-cyano-N’-((2-oxo-1,2-dihydroquinolin-3-yl)methylene)acetohydrazide. Synth. Commun. 51(22), 3366–3378 (2021).

Mahmoud, N. F. H. & El-Sewedy, A. Facile synthesis of novel heterocyclic compounds based on pyridine moiety with pharmaceutical activities. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 57(4), 1559–1572 (2020).

Mahmoud, N. F. H. & Ghareeb, E. A. Synthesis of novel substituted tetrahydropyrimidine derivatives and evaluation of their Pharmacological and antimicrobial activities. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 56(1), 81–91 (2019).

Ramadan, S. K. et al. Synthesis, SAR studies, and insecticidal activities of certain N-heterocycles derived from 3-((2-chloroquinolin-3-yl)methylene)-5-phenylfuran-2(3H)-one against Culex pipiens L. Larvae. RSC Adv. 12(22), 13628–13638 (2022).

Mahmoud, N. F. H. & Balamon, M. G. Synthesis of various fused heterocyclic rings from thiazolopyridine and their Pharmacological and antimicrobial evaluations. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 57(8), 3056–3070 (2020).

Ramadan, S. K., Abd-Rabboh, H. S., Gad, N. M., Abou-Elmagd, W. S. I. & Haneen, D. S. Synthesis and characterization of some chitosan-quinoline nanocomposites as potential insecticidal agents. Polycycl. Aromat. Compds. 43(8), 7013–7026 (2023).

El-Helw, E. A. E., Asran, M., Azab, M. E., Helal, M. H. & Ramadan, S. K. Synthesis, cytotoxic, and antioxidant activity of some Benzoquinoline-Based heterocycles. Polycycl. Aromat. Compds. 44(9), 5938–5950 (2024).

Hassaballah, A. I., Ramadan, S. K., Rizk, S. A., El-Helw, E. A. E. & Abdelwahab, S. Ultrasonic promoted regioselective reactions of the novel Spiro 3,1-benzoxazon-isobenzofuranone dye toward some organic base reagents. Polycycl. Aromat. Compds. 43(4), 2973–2989 (2023).

Gouda, M. A., Salem, M. A. & Mahmoud, N. F. H. 3D-pharmacophore study molecular Docking and synthesis of pyrido[2,3‐d]pyrimidine‐4(1H)-dione derivatives with in vitro potential anticancer and antioxidant activities. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 57, 3988–4006 (2020).

Cun-Jin, Y. Q. Shi J. Chem. Crystalloger 41, 1816. (2011).

Abd El-Latif, F. M., Barsy, M. A., Elrady, E. A. & Hassan, M. J. Chem. Res. (S) 12, 696. (1999).

Abd El-Latif, F. M. A study on 1-Phenyl-3-methyl-5-chloropyrazole-4-carboxaldehyde: synthesis of fused pyrazole, isoxazole, pyrimidine and Pyridine-[2,3-d]pyrazoline derivatives. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 71, 631–634 (1994).

Ramadan, S. K., El-Helw, E. A. E. & Azab, M. E. 2-Cyano-N′-[(1,3-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)methylidene]acetohydrazide in the synthesis of nitrogen heterocycles. Russ J. Org. Chem. 55(12), 1940–1945 (2019).

Gouda, M. A., Salem, M. A., Marzouk, M. I., Mahmoud, N. F. & Ismail, M. F. Synthesis, antioxidant and antiproliferative evaluation, molecular Docking and DFT studies of some novel coumarin and fused coumarin derivatives. Chem. Biodiv 20(7), e202300706 (2023).

Elgubbi, A. S., El-Helw, E. A. E., Alzahrani, A. & Ramadan, S. K. Synthesis, computational chemical study, antiproliferative activity screening, and molecular Docking of some thiophene-based Oxadiazole, Triazole, and Thiazolidinone derivatives. RSC Adv. 14(9), 5926–5940 (2024).

Elgubbi, A. S., El-Helw, E. A. E., Abousiksaka, M. S. & Alzahrani, A. Y. Ramadan, β-Enaminonitrile in the synthesis of tetrahydrobenzo[b]thiophene candidates with DFT simulation, in vitro antiproliferative assessment, molecular docking, and modeling pharmacokinetics. RSC Adv. 14(26), 18417–18430 (2024).

Reed, L. J. & Muench, H. A simple method of estimating 50% end point. Amer J. Hyg. 27, 493 (1938).

Takasty, G. X. The use of spiral loops in serological and virological method. Acta Microb. Hung. 3, 191 (1966).

Ramadan, S. K., Abd-Rabboh, H. S., Hafez, A. A. & Abou-Elmagd, W. S. I. Some pyrimidohexahydroquinoline candidates: synthesis, DFT, cytotoxic activity evaluation, molecular docking, and in Silico studies. RSC Adv. 14(23), 16584–16599 (2024).

El-Sewedy, A., El-Bordany, E. A., Mahmoud, N. F. H., Ali, K. A. & Ramadan, S. K. One-pot synthesis, computational chemical study, molecular docking, biological study, and in Silico prediction ADME/pharmacokinetics properties of 5-substituted 1H-tetrazole derivatives. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 17869 (2023).

RCSB PDB ID web page. https://www.rcsb.org/structure/3MU3

Badran, A. S. & Ibrahim, M. A. Synthesis, spectral characterization, DFT and in Silico ADME studies of the novel pyrido[1,2-a]benzimidazoles and pyrazolo[3,4-b] pyridines. J. Mol. Struct. 1274, 134454 (2023).

Ramadan, S. K. et al. Synthesis, in vivo evaluation, and in Silico molecular Docking of benzo[h]quinoline derivatives as potential Culex pipiens L. larvicides. Bioorg. Chem. 154, 108090 (2025).

Allan, W. H. & Gough, R. A standard hemagglutination Inhibition test for Newcastle disease (2) vaccination and challenge. Vet. Rec. 95(7), 147 (1974).

Code of American Federal Regulations National Archives and Records Administration. Chapter I-Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, Subchapter F-Biologics. Biological products: general title 21, 7 (part 600–799) (2012).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AE did the chemical experiments. EAE, NFHM, and SKR conceptualized and supervised the work. ARIM and SZM did the biological assay and interpretation. SKR characterized the prepared compounds and wrote the main manuscript. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Agricultural Research Center (Approval code: ARC, CLEVB, 161, 24) and was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institute of Health (NIH). All methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. Euthanasia was performed using carbon dioxide inhalation in accordance with AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of animals. The animals were monitored for cessation of vital signs, including heartbeat and respiratory effort, to confirm death before disposal.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Sewedy, A., Morsy, A.R.I., El-Bordany, E.A. et al. Antiviral activity of newly synthesized pyrazole derivatives against Newcastle disease virus. Sci Rep 15, 18745 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03495-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03495-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Recent advances in carbonyl infused bis-pyrazoles: relevance, synthetic developments and biological significance

Molecular Diversity (2026)

-

Synthesis and insecticidal activity of some pyrazole, pyridine, and pyrimidine candidates against Culex pipiens L. larvae

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Synthesis, antiproliferative screening, and molecular docking of some heterocycles derived from N-(1-(5-chloro-3-methyl-1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-3-hydrazineyl-3-oxoprop-1-en-2-yl)benzamide

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Exploring the potential of coumarin-indole hybrid scaffold as promising pharmacological agents: a review

Discover Chemistry (2025)