Abstract

The aim of this study was to translate and adapt the MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI) questionnaire into Finnish and validate it in patients with head and neck cancer (HNC). A total of 94 participants were included: 64 dysphagic HNC patients and 30 non-dysphagic age- and gender-matched controls. The MDADI was formally translated using the forward-backward method and feasibility, test-retest reliability, internal consistency, score distribution, known-group validity, and patient feedback and were analyzed. Criterion and convergent validities were tested against the previously validated dysphagia questionnaire F-EAT-10. The results showed good variability and no floor or ceiling effects in the dysphagic group (age range 31 to 85 years, mean 67.8, SD 11.2). In all MDADI subscales, the internal consistency reliability was high (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.8). Moreover, the intraclass correlation in test-retest (n = 55) was high (> 0.9) in all subscales. The MDADI was able to discriminate between dysphagic and non-dysphagic participants: the mean total score was 73.6 for the dysphagic group and 99.9 for the control group (p > 0.001). The correlations between the MDADI and the F-EAT-10 were strong demonstrating criterion and convergent validities. Patient feedback of the MDADI was positive. In conclusion, the Finnish MDADI is a valid instrument to assess dysphagia-related quality of life in patients with HNC, offering enhanced clinical and research utility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) is the seventh most common malignancy worldwide, accounting for more than 900,000 cases annually1. At diagnosis, up to 28% of all HNC patients report swallowing difficulties (dysphagia)2. Moreover, dysphagia is a common side effect of HNC treatments, thus ultimately affecting up to 45% of HNC survivors3. It is also shown to highly correlate with worse overall quality of life in oropharyngeal cancer patients4.

At present, there are no disease-specific validated Finnish swallowing questionnaires developed for HNC patients. To date, the only validated Finnish swallowing questionnaire is the Finnish version of the Eating Assessment Tool (F-EAT-10)5. The F-EAT-10 is a generic 10-item tool validated in patients with dysphagia of various etiology: in the validation study, the most common causes for dysphagia were functional (26.5%), neurological (12.8%), esophageal (12.0%), and age-related dysphagia (10.3%). Furthermore, the etiology of dysphagia was HNC or esophageal cancer in 13.7% of the patients. The sensitivity of the F-EAT-10 may be insufficient for HNC patients because of the small number of questions6.

In HNC patients, MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI) has shown high internal consistency and reliability7. It has been successfully validated in various cultures and languages in Europe8,9,10,11,12,13, Asia14,15,16,17,18,19, and Latin America20. A preliminary Finnish translation of MDADI has already been used in published research, although it is yet to be validated21,22,23.

This study aimed to translate, adapt, and validate the Finnish version of the MDADI in HNC patients with dysphagia, and contrast it to an age- and gender-matched control group without dysphagia. Following validation guidelines, we aimed to evaluate its psychometric properties by analyzing the internal consistency, the test-retest reliability, the feasibility, the construct validity, and ceiling and floor effects24.

Materials and methods

Patients

A list of survivors with head and neck cancer diagnosed between January 2010 and December 2021 who had received radiation therapy in Turku University Hospital was collected from Auria Clinical Informatics (n = 146). According to the evaluation of the clinician recorded in the patient charts, 138 of these patients had permanent symptoms of dysphagia. These patients were recruited by phone. Patients who reported significant dysphagia that affects their daily life in the phone interview and who gave written informed consent to participate were included in the study.

In addition, we recruited a sample of age- and gender-matched non-dysphagic controls (n = 30) from the local community. The control group included nonhospitalized participants who also gave written informed consent. For non-dysphagic controls, the inclusion criteria were specified as follows: Finnish as native language, no previous HNC, no self-reported dysphagia, and no previous head and neck radiation therapy.

A mail-out/mail-back procedure was used: the MDADI and the F-EAT-10 questionnaires were mailed to all participants. Moreover, the dysphagic participants were asked to give written feedback about the MDADI questionnaire: whether the questions were easy to understand, and other comments. Furthermore, all dysphagic participants were asked to complete the MDADI questionnaire again on a second occasion one week after the time of enrollment. Patients who did not return the questionnaires were not reminded.

The study plan was reviewed by the Regional Ethics Committee (26/1801/2022) at Turku University Hospital. The Ethics Committee decided that since this study does not involve an intervention, the Medical Research Act (Finlex No. 488/1999) does not apply to this study. Hence, no ethical approval was required, and that the study could be performed without further ethical review. The research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient-Reported outcome measures

The MDADI

The MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI) was developed in the United States in 2001. It is a self-administered questionnaire designed specifically for evaluating the impact of dysphagia on the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients with head and neck cancer. The questionnaire consists of six subscales: global (one question), emotional (6 questions), functional (5 questions), physical (8 questions), composite (19 questions), and total (all 20 questions). The global assessment question demonstrates how swallowing limits the patient’s overall QoL. The other subscales have multiple questions relating to the same domain. The emotional subscale consists of affective responses to dysphagia. The functional subscale represents the impact of dysphagia on daily activities. The physical subscale demonstrates self-perceptions of dysphagia. In an individual’s within-subject MDADI scores, a change of 20 points is interpreted meaningful25, whereas between groups of HNC patients, a 10-point difference in composite MDADI scores is associated with clinically meaningful between-group differences in swallowing function26.

In the original English MDADI, two of the items (E7 and F2) included a negation, and thus were scored as 5 points for strongly agree and 1 point for strongly disagree. All other items were scored as 1 point for strongly agree and 5 points for strongly disagree. Therefore, a higher MDADI score indicated better QoL. However, in the validation process of the Swedish MDADI, a systematic error was noted in the two reversed items (E7 and F2)27. Several participants systematically misinterpreted the negation and answered in the same way as to all other items. This systematic error was confirmed by interviews. Therefore, the Swedish version of MDADI was revised so that all items are scored as 1 point for strongly agree and 5 points for strongly disagree28. We decided to follow the Swedish example to avoid this systematic error.

The F-EAT-10

The Finnish version of the Eating Assessment Tool (F-EAT-10) is the only previously validated dysphagia questionnaire for Finnish speakers. In Europe, it has also been validated in Spain29, Italy30, Portugal31, Sweden27, Türkiye32, Greece33, the Netherlands34, and France35. The original EAT-10 was developed in the United States in 2008 to provide a rapid dysphagia instrument. It consists of ten items related to main aspects of dysphagia. All items are scored from no difficulty (0 points) to severe difficulty (4 points). A sum score of > 2 points is regarded suggestive of dysphagia. The MDADI was referenced against the F-EAT-10 to establish criterion validity. We hypothesized that MDADI scores correlate well with F-EAT-10 scores, as both questionnaires measure the same concept of swallowing-related QoL. Written consent to include the F-EAT-10 in this article was requested from Janet Skates, Nestlé Health Science Consultant.

Translation of the MDADI into Finnish

We translated the MDADI using the formal forward-backward method according to Wild et al.36 Initially, our group of native Finnish-speaking medical professionals developed two independent forward translations of the MDADI questionnaire from English to Finnish. Of these preliminary translations, our group developed a single forward translation. Thereafter, a back translation was performed by a native English-speaking professional translator. Finally, two independent otolaryngologists, an independent speech therapist, and an independent nutritionist evaluated the original and the back-translation. In comparison of these questionnaires, the main difference was the removal of the negation in the items E7 and F2, as explained above. No critical differences were found.

Statistics

IBM SPSS Statistics version 29 was used in the statistical analyses. For testing between two groups, the Mann-Whitney test was used, and for testing between > 2 groups, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Correlations were tested with Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r), where a correlation coefficient < 0.3 was considered a weak correlation, 0.3–0.7 moderate correlation, and > 0.7 a strong correlation37. Internal consistency reliability was tested with Cronbach’s α coefficient. Test-retest reliability was analyzed with intraclass correlation (ICC) by longitudinally comparing the questionnaire at the time of enrollment and 7 days after. Known-group validity was calculated between the dysphagic group and the non-dysphagic control group. Floor and ceiling effects were considered present if more than 15% of respondents achieved the extreme summary score38. Our hypothesis was that the non-dysphagic control group would include the most highly functioning participants and represent the highest possible score (ceiling).

Results

Recruitment of participants

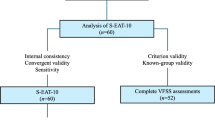

Of the 65 eligible HNC patients, 64 returned written consent to participate (Fig. 1). The response rate was 98.5%. Thus, a total of 94 participants were included in this study: 64 patients with HNC in the dysphagic study group, and 30 age- and gender-matched non-dysphagic controls. The clinical characteristics of all the participants are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Feasibility

All participants had completely finished the questionnaires they returned. There were no missing values. Therefore, the survey had 100% feasibility within the studied population.

Test-Retest reliability

All participants with HNC were asked to fill in a second administration of the MDADI, mailed seven days after the first administration. It was returned by 55 (85.9%) of the participants. The test-retest reliability was good39 for each subscale (intraclass correlation coefficient ICC > 0.80), Table 3.

Internal consistency

For each subscale, the internal consistency was high regarding the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (> 0.80) in the dysphagic group, Table 3. The global subscale consists of only one item, and thus its Cronbach’s alpha coefficient could not be calculated.

Features of score distribution

In all subscales, the full range (20 to 100) of the score distribution was observed in the dysphagic HNC group (Table 4). However, in the non-dysphagic control group, the ranges were small with ceiling effects in all subscales, as expected, Table 4.

Criterion and convergent validities

Criterion and convergent validities were assessed in the dysphagic group by correlations between the MDADI and the previously validated F-EAT-10, Table 5. We hypothesized high negative correlations between the MDADI total and composite subscales and the F-EAT-10 total score (higher QoL with lower symptom burden).

As expected, a strong negative correlation (Spearman’s correlation coefficient r<−0.70) was found between F-EAT-10 total score and the MDADI total, composite, emotional, functional, and physical subscales. Moreover, a strong negative correlation was found between the F-EAT-10 RP (reduced pleasure of eating) and the MDADI total, composite, emotional, functional, and physical subscales. Furthermore, the F-EAT-10 SSD (swallowing solids disorder) had strong negative correlation with the MDADI total, composite, emotional, and physical subscales. A single weak correlation was found between the F-EAT-10 CD (cough during eating) and the MDADI global subscale (r=−0.213). All other correlations between the MDADI and the F-EAT-10 were moderate (r=−0.7–(−0.3)).

Known-Group validity

The MDADI was able to distinguish between dysphagic HNC patients and non-dysphagic control group, Table 6. There was a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001) between the dysphagic and the non-dysphagic group in all subscales: total, composite, global, emotional, functional, and physical. The mean composite score was 74.3 for the dysphagic group and 99.9 for the non-dysphagic control group (p < 0.001).

Patient feedback

All 64 HNC patients were asked to give written feedback about the MDADI. Most of the patients did not submit feedback. Seven patients wrote that the questions were easy to understand. One patient stated that the F-EAT-10 was easier and quicker to fill in than the MDADI.

Discussion

To optimize the treatment of HNC patients, understanding swallowing-related QoL is essential. However, no Finnish dysphagia-specific questionnaires designed for HNC patients have yet been validated. This study translated and cross-culturally adapted the original English MDADI into a Finnish version, and evaluated its validity and reliability among dysphagic patients with HNC compared to an age- and gender-matched non-dysphagic control group.

The Finnish MDADI showed good psychometric properties. It was also able to discriminate between dysphagic and non-dysphagic participants with statistically significant differences in all subscales (p < 0.001). The composite score between-group difference between the dysphagic and the non-dysphagic group was 25.6 points, which means it is also interpreted as clinically meaningful (≥ 10 points)26.

Although all dysphagic participants were asked to give feedback about the MDADI, only eight (12.5%) participants provided written feedback. Seven of the responses were positive, stating all MDADI items were easy to understand. One participant remarked that the F-EAT-10 was easy and quick compared to the MDADI. The MDADI includes double the amount of questions compared to the F-EAT-10, and therefore also gives more elaborate information about dysphagia-related QoL. In routine clinical practice outside of research settings, a shorter questionnaire may be more appropriate than the MDADI. In a recent study, it appeared feasible to abbreviate the 20-item MDADI questionnaire to a 5-item “MiniDADI” questionnaire40.

This study has several limitations. We did not perform structured interviews about the comprehensibility of the MDADI; however, we collected written feedback. Moreover, we had no data about the diet of the participants. However, the MDADI aims to measure subjective QoL, and thus the diet may not be important to include in analyses. In this article, we lack analysis of the responsiveness of the instrument41, but in a Swedish longitudinal study, the MDADI was found to be sensitive to change and to show convergent results against other established instruments28.

The strengths in our study were the inclusion of an age- and gender-matched control group, good balance with education and marital status, good gender and age balance, and a longitudinal test-retest measurement returned by many patients. In addition, our study population represented many HNC subsites. The clinical characteristics and comorbidities were well known in both the dysphagic and the non-dysphagic study groups. Furthermore, we collected and received good patient feedback about the clarity of the Finnish MDADI.

Valid QoL instruments are essential in evaluation of outcomes of new treatments. Moreover, most HNC patients find QoL questionnaires (QLQs) useful to communicate their health concerns to their clinician42. QoL instruments may even be able to predict future QoL and survival43.

Conclusions

The Finnish version of the MDADI showed good validity and reliability. Moreover, it was able to differentiate between dysphagic and non-dysphagic patients. Furthermore, it could assess the severity of the impact of dysphagia on QoL and social functioning. Therefore, it can be used clinically to measure the swallowing-related QoL among HNC patients in Finland and to compare the outcomes of different treatment modalities for HNC.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/CAAC.21660 (2021).

Raber-Durlacher, J. E. et al. Swallowing dysfunction in cancer patients. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1342-2 (2011).

Hutcheson, K. A. et al. Two-year prevalence of dysphagia and related outcomes in head and neck cancer survivors: an updated SEER-Medicare analysis. Head Neck. 41, 479–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/HED.25412 (2019).

Hunter, K. U. et al. Toxicities affecting quality of life after Chemo-IMRT of oropharyngeal cancer: prospective study of Patient-Reported, Observer-Rated, and objective outcomes. Int. J. Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 85, 935–940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.08.030 (2013).

Järvenpää, P. et al. Finnish version of the eating assessment tool (F-EAT-10): A valid and reliable Patient-reported outcome measure for dysphagia evaluation. Dysphagia https://doi.org/10.1007/S00455-021-10362-9 (2021).

Ekström, L., Sjökvist Wilk, L., Finizia, C. & Tuomi, L. Validation of the Swedish eating assessment tool, S-EAT-10, for patients with head and neck cancer. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-025-97170-5 (2025).

Chen, A. Y. et al. The Development and Validation of a Dysphagia-Specific Quality-of-Life Questionnaire for Patients With Head and Neck Cancer: The M.D. Anderson Dysphagia Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 127, 870–876 (2001).

Carlsson, S. et al. Validation of the Swedish M. D. Anderson dysphagia inventory (MDADI) in patients with head and neck cancer and neurologic swallowing disturbances. Dysphagia 27, 361–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00455-011-9375-8 (2012).

Speyer, R. et al. Quality of life in oncological patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia: validity and reliability of the Dutch version of the MD Anderson dysphagia inventory and the deglutition handicap index. Dysphagia 26, 407–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-011-9327-3 (2011).

Montes-Jovellar, L. et al. Translation and validation of the MD Anderson dysphagia inventory (MDADI) for Spanish-speaking patients. Head Neck. 41, 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/HED.25478 (2019).

Lechien, J. R. et al. Validity and reliability of a French version of M.D. Anderson dysphagia inventory. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 277, 3111–3119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06100-w (2020).

Schindler, A. et al. (MDADI) - PubMed. https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.ezproxy.utu.fi/18767327/ (2022).

Hajdú, S. F. et al. Cross-Cultural translation, adaptation and reliability of the Danish M. D. Andeson dysphagia inventory (MDADI) in patients with head and neck Cancer. Dysphagia 32, 472–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-017-9785-3 (2017).

Alsubaie, H. M. et al. Validity and reliability of an Arabic version of MD Anderson dysphagia inventory (MDADI). Dysphagia. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-021-10356-7 (2021).

Kwon, C. H. et al. Validity and reliability of the Korean version of the MD Anderson dysphagia inventory for head and neck Cancer patients. Ann. Rehabil Med. 37, 479–487. https://doi.org/10.5535/ARM.2013.37.4.479 (2013).

Fakhriani, R., Surono, A. & Rianto, B. U. D. Translation and validation of the Indonesian MD Anderson dysphagia inventory (MDADI) in head and neck Cancer patients with swallowing disorders. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 26, E321–E326. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-0041-1735566 (2021).

Yee, K. et al. Validity and reliability of the MD Anderson dysphagia inventory in english and Chinese in head and neck cancer patients. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 16, 372–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/AJCO.13384 (2020).

Matsuda, Y. et al. Reliability and validity of the MD Anderson dysphagia inventory among Japanese patients. Dysphagia 33, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-017-9842-y (2018).

Waghmare, C. M., Aggarwal, V. V., Bhanu, A. & Ravichandran, M. Marathi translation, linguistic validation, and cross-cultural adaptation of M.D. Anderson dysphagia inventory in patients of head and neck squamous cell cancer. Indian J. Cancer. 60, 199–205. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJC.IJC_1006_20 (2023).

Guedes, R. L. V. et al. Validation and application of the M.D. Anderson dysphagia inventory in patients treated for head and neck cancer in Brazil. Dysphagia 28, 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-012-9409-x (2013).

Ranta, P. et al. Long-term quality of life after treatment of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope 131, E1172–E1178. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29042 (2021).

Lahtinen, S. et al. Swallowing-related quality of life after free flap surgery due to cancer of the head and neck. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 276, 821–826. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00405-018-05264-W (2019).

Dzioba, A. et al. Functional and quality of life outcomes after partial glossectomy: a multi-institutional longitudinal study of the head and neck research network. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 46 https://doi.org/10.1186/S40463-017-0234-Y (2017).

Timmerman, A. A., Speyer, R., Heijnen, B. J. & Klijn-Zwijnenberg, I. R. Psychometric characteristics of health-related quality-of-life questionnaires in oropharyngeal dysphagia. Dysphagia 29, 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00455-013-9511-8 (2014).

Lu, W. et al. Acupuncture for dysphagia after chemoradiation in head and neck cancer: rationale and design of a randomized, Sham-Controlled trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 33, 700. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CCT.2012.02.017 (2012).

Hutcheson, K. A. et al. What is a clinically relevant difference in MDADI scores between groups of head and neck cancer patients? Laryngoscope 126, 1108–1113. https://doi.org/10.1002/LARY.25778 (2016).

Möller, R., Safa, S. & Östberg, P. Validation of the Swedish translation of eating assessment tool (S-EAT-10). Acta Otolaryngol. 136, 749–753. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016489.2016.1146411 (2016).

Tuomi, L. et al. A longitudinal study of the Swedish MD Anderson dysphagia inventory in patients with oral cancer. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 5, 1125–1132. https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.490 (2020).

Peláez, R. B. et al. [Translation and validation of the Spanish version of the EAT-10 (Eating assessment Tool-10) for the screening of dysphagia]. Nutr. Hosp. 27, 2048–2054. https://doi.org/10.3305/NH.2012.27.6.6100 (2012).

Schindler, A. et al. Reliability and validity of the Italian eating assessment tool. Ann. Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 122, 717–724. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348941312201109 (2013).

Nogueira, D. S., Ferreira, P. L., Reis, E. A. & Lopes, I. S. Measuring outcomes for dysphagia: validity and reliability of the European Portuguese eating assessment tool (P-EAT-10). Dysphagia 30, 511–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00455-015-9630-5 (2015).

Demir, N., Serel Arslan, S., İnal, Ö. & Karaduman, A. A. Reliability and validity of the Turkish eating assessment tool (T-EAT-10). Dysphagia 31, 644–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00455-016-9723-9 (2016).

Printza, A. et al. Reliability and validity of the eating assessment Tool-10 (Greek adaptation) in neurogenic and head and neck cancer-related oropharyngeal dysphagia. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 275, 1861–1868. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00405-018-5001-9 (2018).

Chung, C. Y. J., Perkisas, S., Vandewoude, M. F. J. & De Cock, A. M. Validatie Van de EAT-10 in Het Nederlands Ter screening Van orofaryngeale dysfagie in Een oudere populatie. Tijdschr Gerontol. Geriatr. 50 https://doi.org/10.36613/TGG.1875-6832/2019.04.03 (2019).

Lechien, J. R. et al. Validity and reliability of the French version of eating assessment tool (EAT-10). Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 276, 1727–1736. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00405-019-05429-1/TABLES/8 (2019).

Wild, D. et al. Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: Report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation Background and Rationale. Value in health 8(2), (2005).

Akoglu, H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 18, 91–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TJEM.2018.08.001 (2018).

Mchorney, C. A. & Tarlov, A. R. Individual-Patient monitoring in clinical practice. Are Available Health Status Surv. Adequate? Res. 4, 293–307 (1995).

Koo, T. K. & Li, M. Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 15, 155. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCM.2016.02.012 (2016).

Lin, D. J. et al. Psychometric properties of the MDADI-A preliminary study of whether less is truly more?? Dysphagia 37, 323–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00455-021-10281-9 (2022).

Yang, L. et al. Cultural adaptation and validation of questionnaires for evaluation of Health-Related quality of life with dysphagia in different countries: A systematic review. Dysphagia 37, 812–823. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00455-021-10330-3/TABLES/3 (2022).

Mehanna, H. et al. Patient preference for commonly-used, head and neck cancer-specific quality of life questionnaires in the follow-up setting (Determin): A multi-centre randomised controlled trial and mixed methods study. Clin. Otolaryngol. 48, 613–622. https://doi.org/10.1111/COA.14054 (2023).

Mehanna, H. M., De Boer, M. F. & Morton, R. P. The association of psycho-social factors and survival in head and neck cancer. Clin. Otolaryngol. 33, 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1749-4486.2008.01666.X (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Vaasa Medical Foundation, the Cancer Society of South-West Finland, the Emil Aaltonen Foundation, the Irja Karvonen Cancer Foundation, the Paulo Foundation, the Cancer Foundation Finland, the Juhani Aho Medical Research Foundation, and the State Research Funding for supporting this work. Moreover, we acknowledge MD, PhD Eeva Haapio, MD, PhD Jarno Velhonoja, MSc (speech and language therapy) Tarja Karttunen, and MSc (nutrition therapy) Nora Löf for participating in the translation process of the Finnish MDADI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (PR, IK, and HI) planned the study together. PR recruited the participants. PR conducted the statistical analyses. All authors participated in the writing process of the manuscript. PR prepared the tables and the figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ranta, P., Kinnunen, I. & Irjala, H. Validation of the Finnish MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI) in patients with head and neck cancer. Sci Rep 15, 18980 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03616-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03616-1