Abstract

To improve the scheduling efficiency of flexible job shops, this paper proposes a multi-objective collaborative intelligent agent reinforcement learning algorithm based on weight distribution. First, a mathematical model for flexible job shop scheduling optimization is established, with the makespan and total energy consumption of the shop as optimization objectives, and a disjunctive-graph is introduced to represent state features. Second, two intelligent agents are designed to address the simultaneous decision making problems of jobs and machines. Encoder-decoder components are implemented to facilitate state recognition and action output by the agents. Reward parameters are computed based on temporal differences at various moments, constructing a multi-objective Markov decision-process training model. Using hypervolume, set coverage and inverted generational distance as evaluation metrics, the algorithm is compared with those proposed in other studies on standard instances. The results demonstrate that the proposed method significantly outperforms other algorithms in solving the flexible job shop scheduling problem. Finally, a real-world case study further validates the effectiveness and practicality of the proposed algorithm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Scheduling plays an irreplaceable role in flexible job shop processing and production. Proper shop floor scheduling not only improves product conversion efficiency and maximises resource utilisation, it is also a key means of reducing pollution emissions and production costs. Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem (FJSP) was thus proposed, where FJSP breaks the constraint that only one machine can be chosen for each process, allowing multiple machines to be selected for each process, and the processing times of the machines corresponding to each process are also different1. Compared with traditional job shops, flexible job shops can better cope with the processing needs of multi-variety and customized products. This flexibility and automation also make the optimization of flexible job shop one of the challenges faced by researchers.

The FJSP is a classic multi-objective optimization problem. As production processes improve, enterprises increasingly demand higher universality and precision in multi-objective optimization solutions. Multi-objective decision-making methods, such as TOPSIS2, COPRAS3, and RSM4,5, are used to rank and select optimal solutions from existing sets. Meanwhile, advancements in machine learning have led to the development of intelligent multi-objective optimization algorithms to enhance solution quality. Notable examples include the Genetic Algorithm (GA)6, Tabu Search (TS)7, Artificial Bee Colony (ABC)8, Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA)9, and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO)10.

Current FJSP solution methods fall into two categories: exact and approximate. Exact solution methods search the entire solution space in the form of mathematical models for planning to find the optimal solution; approximate solution algorithms include heuristic algorithms, meta-heuristic algorithms, and machine learning algorithms to find the approximate optimal solution. Although these algorithms differ in their search mechanisms and optimization strategies, they fundamentally explore combinations of workpiece and machine sequences to enhance solution quality. However, group intelligence algorithms often sacrifice computational efficiency for solution quality. For different case studies, they typically require recomputation, which often results in excessively long solving times. In order to balance solution quality and cost, FJSP research has shifted from traditional heuristic and meta-heuristic algorithms to machine learning-based approaches, such as Deep Learning (DL) algorithms and Reinforcement Learning (RL) algorithms. In recent years, there has been an increase in solving combinatorial optimisation problems by employing reinforcement learning methods, which model the combinatorial optimisation problem as a Markov decision-making model, where the optimality is achieved by continuous updating of the strategies.

Currently, most of the research on solving the FJSP using Reinforcement Learning focuses on the design and improvement of the Markov decision process in the algorithm. Reinforcement Learning was first applied to shop floor scheduling by Riedmiller11, who used Q-learning to train the agent by learning the shop floor’s scheduling strategy, thus demonstrating the good applicability of reinforcement learning algorithms in solving shop floor scheduling. Gui et al.12 used the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) algorithm to train the agent, which makes decisions based on the distribution of policies corresponding to different scheduling rules output by the agent. The optimal scheduling strategy is then derived by selecting the most suitable policy among these. Du et al.13 proposed a multi-objective FJSP mathematical model incorporating crane transportation and installation time. This model utilizes weighted values to convert the two objectives of completion time and total workshop energy consumption into a single objective, and employs Deep Q-network (DQN) for optimization. Liu et al.14 adopted a Double Deep Q-network (DDQN) algorithm and proposed specific state and action representations to address the variability of dynamic scheduling. Song et al.15 represented the complex relationships between operations and machines in the workshop using a disjunctive graph and proposed a novel heterogeneous graph neural network architecture framework. This framework captures the global state during the scheduling process, enabling a more effective solution to the FJSP. Luo et al.16 established a multi-objective FJSP mathematical model and introduced two types of agents for optimization. One agent is responsible for selecting the scheduling objectives, while the other agent optimizes those objectives. Wu et al.17 combined a multi-proximal policy optimization algorithm with a multi-pointer network and proposed a reinforcement learning algorithm based on policy and graph neural networks for solving the FJSP with the objective of minimizing the makespan. Jiang et al.18 proposed a multi-objective proximal policy optimization algorithm that employs two types of agents for optimization, and converted multi-objectives into single-objectives based on weight vectors to achieve multi-objective flexible job shop optimisation. Li et al.19 combined convolutional neural networks with the proximal policy optimization algorithm and designed a dual-channel state representation method to achieve the selection of jobs and machines. Zhang et al.20 proposed a D5QN algorithm for solving the FJSP by combining five types of deep reinforcement learning with maximum completion time as the optimisation objective. Xu et al.21 proposed a hierarchical multi-agent deep reinforcement learning approach for distributed IEMS, introducing a novel region model to achieve multi-agent action control. Hu et al.22 summarized multi-agent optimization algorithms that integrate RL with the Attention Mechanism (AM). Chang et al.23 integrated Q-learning into a memetic algorithm and proposed a Reinforcement Learning-enhanced Multi-Objective Memetic Algorithm based on Decomposition (RL-MOMA/D) to solve the Flexible Distributed Resource-Constrained Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem (F-DRCFJSP-WL). Li et al.24 proposed an end-to-end method based on Graph Attention Networks (GAT) and RL, called the Multi-Objective Graph Attention Reinforcement Learning Scheduler (MO-GARLS), to solve the MOFJSP. Shao et al.25 proposed a hybrid search algorithm that integrates leader-following strategy, random flight and RL. Chen et al.26 utilized a Self-Attention Neural Network to extract state information from global and local multi-dimensional data, improving decision-making accuracy, and employed Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to enhance the training effectiveness and sample utilization of RL. The aforementioned methods collectively demonstrate that, compared to conventional rule-based scheduling algorithms for solving the FJSP, RL algorithms yield more satisfactory results.

However, current RL-based scheduling methods still face limitations, including low sample efficiency, high training costs, challenges in multi-objective trade-offs and reward design, and difficulties in multi-agent collaboration. Effectively integrating reinforcement learning with the FJSP to enhance RL’s capability in solving FJSP remains a critical research challenge. This paper proposes a collaborative multi-agent reinforcement learning scheduling method. To address the constraint characteristics of job sequencing and machine allocation in FJSP, we design a hierarchical multi-agent architecture where distinct agents separately execute action decisions for jobs and machines. Two different RL algorithms are employed to update and learn policies for the job-specific and machine-specific agents. The global scheduling state is modeled using a disjunctive graph representation, with graph neural networks (GNNs) introduced to extract state features. Compared to multi-objective optimization methods such as NSGA-II and the Multi-Objective Whale Optimization Algorithm (MOWOA), our approach achieves online decision-making through dynamic interactions between agents and the environment. Our method leverages graph convolutional networks to extract node and edge features and hierarchical collaborative learning to achieve significant improvements in dynamic adaptability, scalability, and multi-objective trade-off precision.

The remaining sections of this paper are structured as follows. In “Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem Description” section introduces FJSP and expounds its constraints. In “Mathematical Model Establishment” section, a multi-objective mathematical model of FJSP with transport time and energy consumption is established with maximum completion time and total energy consumption as the optimization objectives.In “Model Solution” section, a multi-objective collaborative agent reinforcement learning (MOCARL) algorithm is proposed in the form of weight distribution to solve the model, and two agents are designed to solve the simultaneous decision of the jobs and machines in the FJSP. In “Case Study Analysis” section introduces the production technology of guide roller and the application of MOCARL algorithm to solve the production scheduling problem. In “Conclusion” section concludes the paper.

Flexible job shop scheduling problem description

The FJSP is described as follows: Consider a workshop with n jobs \(J=\{ {J_1},{J_2},.{J_n}\}\)and m machines \(M=\{ {M_1},{M_2},.,{M_m}\}\). Each job \({J_i}\) consists of p processes, and there exist precedence constraints among the processes of each job. For each processes, there are more than one machine available for selection. The processing time and power consumption for different operations vary depending on the chosen machine, and the standby power of different machines also differs27. Additionally, the transportation time between different machines for different jobs varies as well. Therefore, constructing an accurate mathematical model for the FJSP must account for constraints such as machine resource limitations, process sequence dependencies, and processing continuity requirements. The mathematical model of FJSP should satisfy the following assumptions28:

-

(1)

All processing information for the jobs is known, and all jobs are available for processing at time 0.

-

(2)

The transportation time and energy consumption for the first processe of each job are considered.

-

(3)

At any given time, each machine can only perform one processe, and each processe is allowed to be processed on only one machine.

-

(4)

All machines cannot be interrupted once processing has started.

-

(5)

There is no precedence relationship between the processes of different jobs, but there is a strict precedence constraint for the processes of the same job, meaning each processe must begin only after the previous one is completed.

-

(6)

There is only one final processing machine for each process for each job.

-

(7)

The end time of transportation for the previous processe of the same job is the start time of the subsequent processe.

-

(8)

Transportation failures for jobs and machine failures during processing are not considered.

Mathematical model establishment

Based on the relevant constraints in FJSP, transportation constraints such as transportation time and energy consumption are introduced. A mathematical model is established with the maximum completion time and energy consumption as optimization objectives.

Maximum completion time mathematical model

The following are the constraint conditions for optimizing the maximum completion time:

There are back-and-forth constraints between processes on the same job:

where \({S_{{\text{ij}}}}\) is the start time of the -th processe of job ; \({T_{ijk}}\) is the processing time of the -th processe of job on machine k; \({D_{{\text{ijk}}}}\) is an integer variable that takes the value of 0 or 1, if the -th processe of job is processed on machine k, it takes the value of 1; otherwise, it takes the value of 0; \({F_{{\text{ij}}}}\) is the completion time of the -th processe of job ; \({T_{i(j - 1)jmk}}\) is the transportation time for moving job from machine \({M_m}\) to machine \({M_k}\) between the (-1)-th and -th processes.

Each processe of every jobs can only be processed once:

When multiple processes are assigned to the same machine, the next processe can only begin after the current processe has been completed.

where \(S_{{i'j'k}}\) is the start time of the ’-th processe of job ’ on machine k.

All processes are non-stop once machined:

All parameter values are positive:

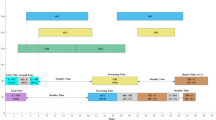

The Gantt chart illustrating the processing time constraints is shown in Fig. 1. A mathematical model is established with the objective of minimizing the maximum completion time.

where \({C_i}\) is the completion time of processing of job .

Mathematical model of total energy consumption for shopfloor machining

During the flexible job shop machining process, the total energy consumption of the workshop can be divided into three aspects: machine tool energy consumption, transportation energy consumption, and other auxiliary energy consumption29. Among these, the optimization potential for other auxiliary energy consumption is limited and difficult to achieve. Therefore, this paper analyzes the sources of energy consumption in workshop production from the perspectives of machine tool machining and transportation.

Machine tool machining energy consumption:

where \({E_c}\)is the total energy consumption of machine \({M_c}\); \(E_{c}^{k}\)is the energy consumption of workpieces processed by machine \({M_c}\); \(P_{c}^{k}\)is the processing power of workpieces by machine \({M_c}\); \(T_{c}^{k}\)is the total processing time for workpieces by machine \({M_c}\).

Machine tool standby energy consumption:

where \({E_{idle}}\)is the total standby energy consumption; \(E_{{idle}}^{k}\)is the standby energy consumption of machine \({M_k}\); \(P_{{idle}}^{k}\)is the standby power of machine \({M_k}\); \(T_{{idle}}^{k}\)is the total standby time of machine \({M_k}\).

Transportation energy consumption:

where \({E_{trans}}\)is the total transportation energy consumption; \({P_{i(j - 1)jmk}}\)is the power for moving job from machine \({M_m}\) to machine \({M_k}\) between the (-1)-th and -th processes.

The total energy consumption of the workshop is the sum of machining energy consumption, standby energy consumption, and transportation energy consumption:

The processing constraints Gantt chart is shown in Fig. 2. A mathematical model is established with the makespan and total workshop energy consumption as optimization objectives, as shown in formulas (12).

The multi-objective problem is transformed into a single-objective problem by introducing the weight \(\omega\), which is the proportion of the objective to maximise completion time.

The disjunctive graph model for flexible job shop scheduling problem

The FJSP can be expressed using a disjunctive graph\(G=(\mathcal{O},\mathcal{C},\mathcal{D})\). Where \(\mathcal{O}\)represents the set of vertices corresponding to all operations, \(\mathcal{O}=\{ {O_{ij}}|\forall i,j\} \cup \{ S,E\}\), S and E denote the start and end times of these operations; \(\mathcal{C}\)represents directed arcs, indicating precedence constraints between consecutive operations of the same workpiece; \(\mathcal{D}\)represents disjunctive arcs, connecting operations that can be processed on the same machine. In Fig. 3, diagrams (a) and (b) represent the disjunctive graphs for a \(\:3\times\:3\) FJSP instance before and after scheduling. Figure 3a illustrates the static situation of the FJSP instance before scheduling, solid black lines represent directed arcs, indicating the precedence constraints between different operations of the same workpiece, while the colored dashed lines represent disjunctive arcs, with different colors corresponding to different processing machines. In Fig. 3b, all operations have been assigned to machines and a processing order has been established between the machines, presenting a complete FJSP scheduling solution.

Model solution

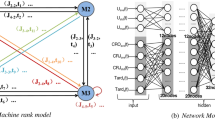

This paper focuses on the multi-objective optimization of the FJSP, considering transportation constraints, with the objective of maximum completion time and total workshop energy consumption. In reinforcement learning algorithms, agents typically learn by optimizing a single objective to achieve the best possible outcome. Therefore, a Multi-Objective Collaborative Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning (MOCARL) algorithm is designed to solve this problem. The proposed algorithm employs two distinct agents to handle job and machine selection, respectively. Specifically, the job agent and machine agent are trained using the PPO algorithm and the D3QN algorithm to enable simultaneous decision-making for jobs and machines in FJSP. In the FJSP framework, The PPO algorithm restricts policy update magnitudes via its clip mechanism, ensuring training stability. The D3QN algorithm addresses Q-value overestimation through Double DQN and Dueling architecture, enhancing precision in machine tool selection. Compared to other algorithms—such as: Asynchronous Advantage Actor-Critic (A3C), Soft Actor-Critic (SAC), Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (TD3), the PPO-D3QN hybrid demonstrates complementary advantages in mixed action space handling, policy stability, and multi-objective coordination.

Neighborhood policy parameter transfer method

The paper adopts a neighborhood policy parameter transfer method30 to decompose the multi-objective problem into i uniformly distributed subproblems defined by weight vectors \(\omega =[{\omega _1},{\omega _2}, \cdots ,{\omega _i}]\). As shown in Fig. 4a, due to the similar weight values between them, two adjacent subproblems tend to have very similar optimal solutions. As shown in Fig. 4b, neighborhood policy parameter transfer method optimizes these i subproblems using a weighted-sum approach, solving for the corresponding optimal solution for each subproblem. The process begins with \({\omega _1}=0.1\), generating an optimal policy parameter \({\theta ^*}^{{{\omega _1}}}\). Subsequently, the subproblem for \({\omega _1}=0.2\)is optimized by initializing the agent’s policy parameters with \({\theta ^*}^{{{\omega _1}}}\), thereby accelerating training through knowledge transfer. After solving all i subproblems, a Pareto frontier is constructed to derive the relatively optimal weight allocation. The detailed algorithmic workflow is summarized in Table 1.

The notable advantage of this neighborhood policy parameter transfer method lies in its modularity and ease of use. This approach allows for more efficient training of the agent’s parameters in a short period. When solving the FJSP with different weights using this method, it is only necessary to replace the subproblem parameters, making it adaptable to different solving requirements. Once trained, the optimal policy can be directly deployed without retraining the entire model.

Multi-objective Markov decision process description

The FJSP can be summarized as a continuous decision-making process with a total horizon of \({\mathbb{O}}\) steps. At each discrete time step t, two agents operate together. First, the job agent indexes the operations that meet the current processing conditions and performs a greedy decision to schedule one job. Then, the machine agent calculates the priority of machines based on the operation of the selected job and ultimately selects a machine through either random sampling or a greedy decision-making approach. This MOCARL-based approach can be modeled using an MDP tuple \((S,A,P,R,\gamma )\). The specific method is described as follows:

State settings

According to the constraints of the FJSP, the state \({s_t}\)at time t is composed of a global state \(s_{t}^{o}\)and a local state \(s_{t}^{m}\). The global state \(s_{t}^{o}\) is represented by a disjunctive graph \(G(t)=(\mathcal{O},\mathcal{C} \cup \mathcal{D}_u(t),\mathcal{D}(t))\) and a weight \(\omega\). Each operation node in the disjunctive graph is composed of three features \([{C_{LB}}({O_{ij}},{s_t}),{E_{LB}}({O_{ij}},{s_t}),I({O_{ij}},{s_t})]\). \(I({O_{ij}},{s_t})\) is a binary variable, equal to 1 if operation \({O_{ij}}\) has been scheduled, and 0 otherwise. \({C_{LB}}({O_{ij}},{s_t})\)and \({E_{LB}}({O_{ij}},{s_t})\)represent the final completion time and the final processing energy consumption of operation \({O_{ij}}\)at state \({s_t}\) respectively. If operation \({O_{ij}}\) has not been scheduled, \({C_{LB}}({O_{ij}},{s_t})\)and \({E_{LB}}({O_{ij}},{s_t})\)represent the estimated completion time and the estimated processing energy consumption, respectively.

The local state \(s_{t}^{m}\)is configured according to the specific agent. For the job agent, its local state \(s_{{t,J}}^{m}\)is composed of four parts [\({T_t}({O_{ij}}),{T_{ijk}},{E_t}({O_{ij}}),{E_{ijk}}\)]. \({T_t}({O_{ij}})\)represents the final completion time after operation \({O_{ij}}\)is processed; \({T_{ijk}}\)represents the processing time of each operation \({O_{ij}}\)on machine \({M_k}\). If machine \({M_k}\)is not compatible with the set of machines \({\Omega _{ij}}\)that can process \({O_{ij}}\), the compatible average processing time is calculated according to formulas (16). \({E_t}({O_{ij}})\)represents the processing energy consumption after operation \({O_{ij}}\)is completed at time ; \({E_{ijk}}\)represents the processing energy consumption of each operation \({O_{ij}}\)on the corresponding machine \({M_k}\). If machine \({M_k}\) is not compatible with the set of machines \({\Omega _{ij}}\) that can process \({O_{ij}}\), the average processing energy consumption is calculated according to formulas (17). For the machine agent, the local state \(s_{{t,M}}^{m}\)is determined by the job selected by the job agent and includes two features [\({T_t}({M_k}),{E_t}({M_k})\)]. \({T_t}({M_k})\)represents the processing end time of each machine in the set of compatible machines \({\Omega _{ij}}\)for the operation selected by the job agent at time t; \({E_t}({M_k})\)represents the energy consumption of each machine in \({\Omega _{ij}}\)at time t.

Action selection

At time t, the action \({a_t}\) consists of two parts, \(a_{t}^{o} \in A_{t}^{o}\)and \(a_{t}^{m} \in A_{t}^{m}\), corresponding to the job agent’s selection of the job to be processed and the machine agent’s selection of the machine for processing, respectively. \(A_{t}^{o}\)represents the set of jobs available for processing by the job agent at time t; \(A_{t}^{m}\)represents the set of machines available for processing the selected operation, as determined by the machine agent at time t.

State transfer

At time , the job agent and machine agent each execute their respective actions \(a_{t}^{o}\)and \(a_{t}^{m}\). Subsequently, the disjunctive graph is updated based on the current action set \({a_t}\), and the updated disjunctive graph is used as the global state for the next time step \(t+1\), as shown in Fig. 5. At the same time, the processing end time \({T_{t+1}}({O_{ij}})\)and processing energy consumption \({E_{t+1}}({O_{ij}})\)of the operation \({O_{ij}}\)in the local state \(s_{{t,J}}^{m}\)of the job agent are updated as the local state \(s_{{t+1,J}}^{m}\)of the job agent at the next time step. \({T_{t+1}}({M_k})\)and \({E_{t+1}}({M_k})\)in the local state \(s_{{t,M}}^{m}\)of the machine agent are updated as the local state \(s_{{t,M}}^{m}\)of the machine agent at the next time step.

Reward parameters

The reward parameters for both the maximum completion time and processing energy consumption are calculated based on the differences between these two objectives at different time steps. The final reward is computed in the form of a weighted distribution of these parameters, and both the job agent and machine agent share this final reward. For the maximum completion time \({R_T}\left( {{s_t},{a_t}} \right)={H_T}\left( {{s_t}} \right) - {H_T}\left( {{s_t}_{{+1}}} \right)\), \({H_T}({s_t})\) represents the estimated maximum completion time at time t, \({H_T}({s_t})={\hbox{max} _{i,j}}\{ {C_{LB}}({O_{ij}},{s_t})\}\); for the final state \({s_{\mathbb{O}}}\), the completion time is \(H({s_{\mathbb{O}}})={C_{\hbox{max} }}\). For processing energy consumption \({R_E}\left( {{s_t},{a_t}} \right)={H_E}\left( {{s_t}} \right) - {H_E}\left( {{s_t}_{{+1}}} \right)\), \({H_E}({s_t})\)represents the estimated total job processing energy consumption at time t; for the final state \({s_{\mathbb{O}}}\), the processing energy consumption is \(H({s_{\mathbb{O}}})={E_c}\). Regarding the final reward parameter \(R\left( {{s_t},{a_t}} \right)={R_T}\left( {{s_t},{a_t}} \right) \times \omega +{R_E}\left( {{s_t},{a_t}} \right) \times (1 - \omega )\).

Policy decision

For the multi-objective problem, the decomposition strategy is implemented using \(\omega\) as the weight parameter, transforming the multi-objective problem into single-objective problems with different values of \(\omega\). For different weight values \(\omega\), using \(\pi _{\theta }^{\omega }=({a_o},{a_m}|s)\)and \({\theta ^\omega }=[\theta _{o}^{\omega },\theta _{m}^{\omega }]\)corresponds to the scheduling strategies and strategy parameters for the agents, respectively. The job agent and machine agent adopt their respective strategies \(\pi _{{{\theta _o}}}^{\omega }({a_o}|s)\)and \(\pi _{{{\theta _m}}}^{\omega }({a_m}|s,{a_o})\), where \(\theta _{o}^{\omega }\)and \(\theta _{m}^{\omega }\)are the strategy parameters for job selection and machine selection, respectively. During the entire scheduling process, the strategies of both agents select actions \(a_{t}^{o}\) from the set of job \(A_{t}^{o}\)and actions \(a_{t}^{m}\) from the set of machines \(A_{t}^{m}\) in the form of a probability distribution.

Encoder-decoder building blocks

An encoder-decoder component is set up for the job agent and machine agent to facilitate the agents’ recognition of states and the output of actions. The encoder identifies information from the environment and outputs the global state and local state, while the decoder outputs the respective actions based on the input states.

Job node encoding

A GNN variant, the Graph Isomorphic Network (GIN)31, is used to capture the features of the global state \(s_{t}^{o}\) of the disjunctive graph at each time step t. The job state information includes both the global and local states, where the global state \(s_{t}^{o}\)is represented in the form of the nodes \(G(t)=(\mathcal{O},\mathcal{C} \cup \mathcal{D}_u(t),\mathcal{D}(t))\)of the disjunctive graph. To reduce computational complexity, an “Arc Addition Strategy"32 is introduced, which ignores undirected arcs in the initial state, as illustrated in Fig. 5. This method prevents the GIN from being unable to effectively extract features due to excessive graph density during the disjunctive graph feature extraction process. In this approach, the neighborhood set \(\mathcal{N}(v)\)of node \(\nu\) is connected using directed arcs, with \({\overline {G} _t}=(\mathcal{O},\mathcal{C} \cup \mathcal{D}_u(t))\)representing the entire disjunctive graph. The extracted features of the FJSP disjunctive graph and the weight \(\omega\)are encoded through a fully connected layer, with the final output being the node embedding \(h_{{v,t}}^{{(K)}}\)and the entire graph pooling vector \(h_{\mathcal{G}}^{t}=1/\mathcal{O}\sum\nolimits_{{v \in \mathcal{O}}} {h_{{v,t}}^{K}}\). The local state \(s_{{t,J}}^{m}\)is represented as \({T_t}({O_{ij}}),{T_{ijk}},{E_t}({O_{ij}}),{E_{ijk}}\)and encoded via a fully connected layer, outputting the embedded state vector \(h_{{J,t}}^{k}\)and the pooling vector \(u_{{J,t}}^{k}\)at each discrete time step t.

Machine node encoding

The machine state does not utilize the graph structure of the global state. Instead, at each time step, node information is represented by local features, without directed or undirected arcs connecting the nodes. The machine state is encoded solely based on the machine’s local state information at time t. At discrete time t, the machine’s local state\(s_{{t,M}}^{m}\) is represented as \({T_t}({M_k}),{E_t}({M_k})\)and encoded through a fully connected layer, ultimately outputting the embedding vector \(h_{{M,t}}^{k}\)for each machine node and the pooling vector \(u_{M}^{t}\).

Decoder

Long Short-Term Memory networks (LSTM), a type of recurrent neural network33, is an important tool for handling sequential data due to their ability to manage long-term dependencies, prevent gradient vanishing, and offer flexibility and wide applicability. By applying LSTM in the decoder, it enhances the recognition of states \(s_{t}^{o}\)and \(s_{t}^{m}\), and the execution of actions \(a_{t}^{o}\)and \(a_{t}^{m}\). The decoders of the two agents share the same network structure, but their network parameters are independent of each other. During the decoding process, each agent decodes based on its own encoding, outputting the selectable job score \(c_{{t,v}}^{o}\)and and the selectable machine score \(c_{{t,k}}^{m}\):

where [, ] denotes the concatenation operation.

To prevent the agents from making decisions on already scheduled jobs and machines that cannot be processed, the corresponding \(c_{{t,v}}^{o}\)and \(c_{{t,k}}^{m}\) are both set to \(- \infty\). The Softmax function is then applied to \(c_{{t,v}}^{o}\)and \(c_{{t,k}}^{m}\)to normalize them, outputting the actions \(a_{t}^{o}\)and \(a_{t}^{m}\)along with the corresponding probability distributions \({p_i}(a_{t}^{o})\)and \({p_k}(a_{t}^{m})\). Finally, the job agent selects the action with the highest probability based on a greedy decision, while the machine agent selects an action according to the probability distribution of \(\varepsilon\).

Algorithm flow implementation

The solution process corresponding to a single weight \(\omega\) is shown in Fig. 6. As seen in the figure, in the MOCARL algorithm, the job agent and machine agent are trained using the PPO and D3QN algorithms, respectively, to optimize their respective network parameters. Both agents operate within the same environment, dynamically sharing reward parameters during learning. Through gradient descent, they iteratively update their network parameters, thereby achieving the dual objectives of collaborative training and multi-objective optimization. The algorithm flow for solving the Multi-Objective Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem (MOFJSP) using the Multi-Objective Collaborative Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning (MOCARL) algorithm is shown in Table 2.

Experimental verification

Algorithm design

Before solving the MOFJSP, the MOCARL algorithm requires a systematic analysis of its hyperparameters to enhance training quality. The algorithm primarily optimizes three critical hyperparameters: learning rate(lr), number of Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN) layers, and number of hidden units per layer in the neural network, to ensure faster convergence and improved stability. Following reference 30, Using the MK09 benchmark as a reference dataset, we randomly generated FJSP instances of the same scale to form the training set. An orthogonal experimental design34 was employed to train the model across all permutations and combinations of the three hyperparameters. By comparing experimental results, the optimal hyperparameter configuration—with learning rate set to 10− 4, GIN layers to 2, and hidden units per layer to 128—was ultimately selected.

To achieve high-quality results under the same conditions for the number of jobs, operations, and machines, the algorithm is trained using randomly generated instances with fixed job, operation, and machine counts. Publicly available FJSP benchmark datasets are used for testing. Based on the test results for different weights, the algorithm retains strategies following a survival-of-the-fittest principle, calculated through weight percentage evaluations:

where f is the objective function; T is the current maximum completion time; E is the current total workshop energy consumption. \({T^*}\)and \({E^*}\) represent the optimal maximum completion time and total energy consumption retained from the previous iteration for the corresponding weight.

To validate the performance of the algorithm, the same dataset from reference35 is used for computation. This dataset is based on the standard data from Brandimart’s MK01-MK07 instances, with further extensions to the machine operating power, as shown in Table 3. The power in the table is measured in units corresponding to the unit power per unit time in the MK01-MK07 data.

Table 4 from reference31 provides the data for the job transportation time between machines, indicating the unit time required to transport a job from one machine to another. The unit power corresponding to the transportation equipment per unit time is a constant value \({P_{trance}}=1.89\).

Comparison of example results

The Pareto solution set obtained after optimization is shown in Table 5. The table compares the Pareto solution sets of MOCARL, MOWPA, and NSGA-II under the extended forms of the MK01-MK07 cases from Brandimart. From the MK01 to MK07 benchmark instances, the problem scale progressively increases, with the number of jobs and machines incrementally rising, thereby gradually escalating scheduling complexity. This design transitions from idealized laboratory conditions to near-industrial-level complexity, aiming to evaluate the effectiveness of innovative scheduling algorithms under scenarios that approximate real-world production challenges. The two objectives in the Pareto solution set are represented as (x; y), where x denotes the maximum completion time, and y represents the total workshop processing energy consumption.

Based on the results in Table 5, the optimization metrics are evaluated using three indicators for multi-objective optimization problems: Hypervolume(HV)36, Set Coverage (SC)37 and Inverted Generational Distance (IGD)38.

Hypervolume

The Hypervolume metric is calculated as the volume of the region in the objective space bounded by the non-dominated solution set obtained by the algorithm and a reference point.

where \(\delta\) denotes the Lebesgue measure, which quantifies the volume; \(\left| S \right|\) is the number of non-dominated solutions in the Pareto set; \({v_i}\) represents the hypervolume dominated by the i-th solution and bounded by the reference point. A higher HV value indicates better comprehensive performance of the algorithm, as it reflects both convergence and diversity of the solution set.

Set coverage

The Set Coverage metric determines the dominance relationship between two solution sets by comparing their mutual coverage.

where \({F_1}\)and \({F_2}\) represent the Pareto frontiers of two algorithms, and \(\left| {{F_2}} \right|\)is the size of \({F_2}\). The \(C({F_1},{F_2})\) denotes the percentage of solutions in \({F_2}\) that are dominated by at least one solution in \({F_1}\). A higher \(C({F_1},{F_2})\) value indicates that solution set \({F_1}\) exhibits superior dominance over \({F_2}\).

Inverted generational distance

The Inverted Generational Distance calculates the average distance between the solutions in the true optimal Pareto set and the non-dominated solution set generated by the algorithm.

where \({F^*}\) represents the non-dominated solution set on the optimal Pareto front, and \(\left| {{F^*}} \right|\)is the number of \(\left| {{F^*}} \right|\). \(d(so{l_1},so{l_2})\) represents the Euclidean distance between solution sol1 from the optimal Pareto set and solution sol2 from the solution set obtained by the algorithm. The smaller the \(IGD({F_1},{F^*})\), the better the convergence and distribution of the obtained solutions.

In the scheduling process described in this paper, since the values in the test cases are set according to actual processing conditions, the true Pareto front is unknown. Therefore, the approximate optimal Pareto front is constructed based on the results obtained from the three algorithms discussed in this paper.

The computational results of the three algorithms for HV, SC, and IGD metrics are presented in Tables 6, 7, and 8, respectively. As shown in the tables, the results obtained by MOCARL dominate the MOWPA and NSGA-II algorithms under the Brandimarte algorithm for most of the algorithms. In the comparative analysis with the MOWPA, the MOCARL algorithm demonstrates robust performance across most benchmark instances. When evaluated via the HV, MOCARL underperforms MOWPA only on the MK07 instance, while outperforming it in all other cases. For SC, MOCARL achieves complete dominance over MOWPA on the MK02 and MK06 instances, though suboptimal dominance is observed on MK04 and MK07. In terms of the IGD, MOCARL exhibits higher values than MOWPA on MK03 and MK04, reflecting poorer distribution quality of solutions in these specific instances. In the comparative analysis with the NSGA-II, the MOCARL algorithm demonstrates superior performance across all benchmark instances when evaluated via the HV metric. Furthermore, based on SC results, MOCARL achieves dominance over NSGA-II in most instances, with only partial dominance observed in MK03, where a subset of solutions remains non-dominated. Regarding the IGD, MOCARL yields higher values than NSGA-II solely in the MK04 instance, while outperforming NSGA-II in all other cases.

Both MOWPA and NSGA-II suffer from high per-iteration time complexity and require retraining for different benchmark instances, resulting in limited adaptability. In contrast, MOCARL, leveraging its distributed training architecture, exhibits superior computational efficiency, scalability, and robust adaptability to high-dimensional objective spaces. Its collaborative multi-agent architecture makes it particularly well-suited for complex scheduling tasks, enabling enhanced production efficiency and reduced operational costs. Comparative analyses with MOWPA and NSGA-II thus confirm that MOCARL has good performance in solving multi-objective problems.

Case study analysis

Taking the actual machining of a guide roller as an example, its structure includes three components: two steel shafts, two aluminum plugs, and one roller. The steel shaft interacts with the bearing to achieve power transmission, thereby driving the guide roller to rotate. The component shapes and manufacturing processes of guide rollers of different models are generally the same. However, the differences lie in the shape of the shaft head, the size of the roller, and the type of surface guide groove, as shown in Fig. 7. Thus, the corresponding machining time and power consumption are not exactly the same for each model. There are 8 kinds of processing steps of the guide roller, and these eight machining processes are subject to sequential processing constraints. The process flow is shown in Fig. 8.

Taking a mechanical workshop of a printing enterprise in Shaanxi Province, China, as an example, the guide rollers are processed on a production line where each workpiece is produced sequentially on the corresponding machines according to the pre-determined process. Transitioning this to a flexible job shop production mode, the workshop is equipped with 4 single-turret turning centers, 2 custom-made high-frequency induction heating devices, 1 single-turret horizontal CNC lathe, 1 dual-turret horizontal CNC lathe, 2 custom micro-arc oxidation production lines, and 1 dynamic balancing machine. Using the processing technology shown in Fig. 8, the machining of five different types of guide rollers is taken as an example, with the process data shown in Table 9. Each machine can only process one operation at a time.

Each machine is connected to a power meter for power recording, and power consumption is analyzed based on the changes during different machine states such as startup, standby, and processing. Ultimately, the machine’s power consumption is divided into two stages: standby power and processing power. The average power values for each stage are calculated, resulting in the average processing power and standby power for each machine. The values for the average standby power and average processing power of different machines are shown in Table 10.

AGV carts are used for transportation between machines in the workshop. The transportation times of the AGV carts between different machines are recorded and shown in Table 11, representing the time required to transport a workpiece from machine Mn to machine Mm. The transportation power of the AGV carts is represented by a constant value, with Ptrans=0.15KW.

The optimal Pareto solution sets under different optimized weight values are shown in Table 12, and the Pareto front curve is plotted as shown in Fig. 9. In the figure, the dots represent the Pareto optimal solution set obtained by the MOCARL algorithm, and the solution corresponding to ω = 0.6 has the best effect, and its scheduling Gantt chart is shown in Fig. 10. In the figure, the X-axis represents processing time, while the Y-axis denotes different machines. Distinct colors are used to denote different workpieces. For tasks sharing the same color, the length of the task block corresponds to the processing time of the current operation for the corresponding workpiece, and its position on the X-axis indicates the start and end times of that operation.

Conclusion

This paper proposes a multi-objective collaborative agent reinforcement learning algorithm for the flexible job shop scheduling problem, and optimizes the scheduling strategy by comprehensively considering the makespan and total energy consumption. Two agents are designed for the selection of workpieces and machines in FJSP, and the PPO algorithm and D3QN algorithm are used to train the agents respectively to solve the model. The MK01-MK07 instances in Brandimarte are used for testing, and the training results are compared with those of the MOWPA and NSGA-II algorithms. This algorithm has good performance in the process of solving multi-objective problems. When this algorithm is applied to the machining example of guide rollers, compared with the machining scheme of the traditional assembly line, the optimized scheduling scheme has reductions in both the makespan and machining energy consumption. In dealing with FJSP, the advantages of this algorithm are as follows:

-

1.

This algorithm model can be flexibly applied to the flexible shop scheduling problem in actual production. As long as the corresponding production data is provided, the corresponding optimal scheduling strategy can be obtained.

-

2.

After the training of this algorithm model is completed, the model can be stored, and the optimal result can be solved in a short time when dealing with other instances.

-

3.

The proposed algorithm further exhibits strong scalability and is applicable to manufacturing systems characterized by multi-device collaboration, frequent dynamic disturbances, and multi-objective conflicts, such as those in the food, pharmaceutical, and automotive manufacturing industries.

The MOCARL algorithm proposed in this paper is mainly used for static scheduling. However, its current framework requires enhancements to address dynamic disruptions such as machine failures, earlier delivery deadlines, and new order insertions. Future work will focus on integrating the algorithm with dynamic shop floor environments by incorporating stochastic perturbations into adversarial training within simulated settings. For instance, introducing probabilistic fluctuations in processing times (e.g., random upward/downward variations) could refine the algorithm’s adaptability to real-world uncertainties, thereby improving its capability in dynamic scheduling scenarios.

Data availability

Data will be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request by the reader.

References

Tian, Y., Tian, Y. N. & Liu, X. Algorithms for solving flexible job shop scheduling problems overview of algorithms for solving flexible job shop scheduling problems. J. Yan’an University(Natural Sci. Ed. 003, 040 (2021).

Singh, N. K., Rathore, R. K., Sinha, A. K. & Narayan, H. Multiobjective optimization of process parameter subjected to end milling process of AA7075 alloy through TOPSIS method. AIP Conf. Proc. 3111, 060004. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0221440 (2024).

Singh, N. K., Balaguru, S., Rathore, R. K., Namdeo, A. K. & Kaimkuriya, A. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making technique for optimal material selection of AA7075/SiC composite foam using COPRAS technique. J. Mines Met. Fuels. 71 (10), 1374–1379. https://doi.org/10.18311/jmmf/2023/34005 (2023).

Krishna, R. & Gupta, P. K. Optimizing pressure drop in 90° bend horizontal pipelines for dense slurry flow: a response surface methodology approach. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E https://doi.org/10.1177/09544089241271765 (2024).

Gupta, P. K., Kumar, N. & Krishna, R. Near-wall flow characteristics in pipe Bend dense slurries: optimizing the maximum sliding frictional power. Int. J. Sediment. Res. 39 (3), 435–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsrc.2024.04.002 (2024).

OuYang, Z. The research and application on job shop scheduling problem based On GA. Zhejiang Umiv. (2004).

Serna, N. J. E. A global-local neighborhood search algorithm and Tabu search for flexible job shop scheduling problem. PeerJ Com. Sci. 7, e574. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.574 (2021).

Zhang, H. N., Tian, X. P., Shun, M. K. & Research on flexible job shop scheduling based on improved artificial bee colony algorithm. M&E Eng. Technol. 53 (01), 106–109 + 129. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1009-9492.2024.01.024 (2024).

Ning, T., Huang, M. & Liang, X. A novel dynamic scheduling strategy for solving flexible job shop problems. J. Amb Intel Hum. Comp. 7 (5), 721–729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-016-0370-7 (2016).

Wu, J., Wu, G. D. & Wang, J. J. Flexible job shop scheduling problem based on hybrid ACO algorithm. Int. J. Simul. Model. 16 (3), 497–505. https://doi.org/10.2507/IJSIMM16(3)CO11 (2017).

Riedmiller, S. & Riedmiller, M. A neural reinforcement learning approach to learn local dispatching policies in production scheduling. IJCAI’99 2, 764–769 (1999).

Gui, Y., Tang, D., Zhu, H., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, Z. Dynamic scheduling for flexible job shop using a deep reinforcement learning approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 180, 109255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2023.109255 (2023).

Du, Y., Li, J., Li, C. & Duan, P. A reinforcement learning approach for flexible job shop scheduling problem with crane transportation and setup times. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks Learn. Syst. 35 (4), 5695–5709. https://doi.org/10.1109/TNNLS.2022.3208942 (2022).

Liu, R., Piplani, R. & Toro, C. Deep reinforcement learning for dynamic scheduling of a flexible job shop. Int. J. Prod. Res. 60 (13), 4049–4069. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2022.2058432 (2022).

Song, W., Chen, X., Li, Q. & Cao, Z. Flexible job-shop scheduling via graph neural network and deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Industr Inf. 19 (2), 1600–1610. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2022.3189725 (2022).

Luo, S. Dynamic scheduling for flexible job shop with new job insertions by deep reinforcement learning. Appl. Soft Comput. 91 (21), 106208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2020.106208 (2020).

Wu, H. Z., Li, Y. W. & Xie, H. Improved proximal policy optimization algorithm for solving flexible job shop scheduling problem. CIMS 1 (2023).

Jiang, Q. & Wei, J. X. Real-time scheduling method for dynamic flexible job shop scheduling. J. Syst. Simul. 36 (07), 1609–1620. https://doi.org/10.16182/j.issn1004731x.joss.23-0385 (2024).

Li, X. Z., Li, Y. W. & Xie, H. Deep reinforcement learning algorithm based on CNN to solve flexible job-shop scheduling problem. CEA 60 (17), 312–320. https://doi.org/10.3778/j.issn.1002-8331.2305-0518 (2024).

Zhang, K., Bi, L. & Jiao, X. G. Research on flexible job-shop scheduling problem with integrated reinforcement learning Algoriyhm. China Mech. Eng. 34 (02), 201–207. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-132X.2023.02.010 (2023).

Xu, X. et al. Collaborative optimization of multi-energy multi-microgrid system: A hierarchical trust-region multi-agent reinforcement learning approach. Appl. Energy. 375, 123923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.123923 (2024).

Hu, K. et al. An overview: Attention mechanisms in multi-agent reinforcement learning. Neurocomputing 598, 128015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2024.128015 (2024).

Chang, X., Jia, X. & Ren, J. A reinforcement learning enhanced memetic algorithm for multi-objective flexible job shop scheduling toward industry 5.0. Int. J. Prod. Res. 63 (1), 119–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2024.2357740 (2025).

Li, Y., Zhong, W. & Wu, Y. Multi-objective flexible job-shop scheduling via graph attention network and reinforcement learning. J. SUPERCOMPUT. 81 (1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-024-06741-2 (2025).

Shao, C. et al. A random flight–follow leader and reinforcement learning approach for flexible job shop scheduling problem. J. SUPERCOMPUT. 81 (3), 478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-025-06935-2 (2025).

Chen, L. et al. Real-time stochastic flexible flow shop scheduling in a credit factory with model-based reinforcement learning. Int. J. Prod. Res. 63 (3), 845–864. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2024.2361441 (2025).

Zhao, S. Bilevel neighborhood search hybrid algorithm for the flexible job shop scheduling problem. J. Mech. Eng. 51 (14), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.3901/JME.2015.14.175 (2015).

Liu, X. B. & Lv, Q. Flexible job shop scheduling based on immune clonal selection principle. Modular Mach. Tool. Automatic Manuf. Technique. 01, 5–10 (2008).

Shi, J. L., Liu, F., Xu, D. J. & Chen, G. R. Decision model and practical method of Energy—saving in NC machine tool. China Mech. Eng. 20 (11), 1344–1346 (2009).

Li, K., Zhang, T. & Wang, R. Deep reinforcement learning for Multi-objective optimization. IEEE T CYBERNETICS. 3, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCYB.2020.2977661 (2019).

Xu, K., Hu, W., Leskovec, J. & Jegelka, S. How powerful are graph neural networks? ICLR https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1810.00826 (2019).

Zhang, C. Learning to dispatch for job shop scheduling via deep reinforcement learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 1621–1632. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2010.12367 (2020).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9 (8), 1735–1780 (1997).

Li, J. Research on flexible job shop scheduling method based on collaborative agent reinforcement learning algorithm. J. Syst. Simul. 23 0978. https://doi.org/10.16182/j.issn1004731x.joss (2023).

Zhang, C. Y. Research of flexible job shop scheduling problem based on energy consumption optimization. HAUST (2022).

Zhang, K., Zhao, S., Zeng, H. & Chen, J. Two-Stage archive evolutionary algorithm for constrained Multi-Objective optimization. Mathematics 13 (3), 470–470. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13030470 (2025).

Zitzler, E. & Thiele, L. Multiobjective evolutionary algorithms: a comparative case study and the strength Pareto approach. IEEE T EVOLUT COMPUT. 3 (4), 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1109/4235.797969 (1999).

Czyzzak, P. & Jaszkiewicz, A. Pareto simulated annealing—a metaheuristic technique for multiple-objective combinatorial optimization. J. Multi-Criteria Dec. 7 (1), 34–47. (1998).

Acknowledgements

This research was Supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No.2023YFB4605100); and the Science and Technology Research Program of He’nan Province (No.212102210356).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.; methodology, S.L. and H.L.; software, S.L. and P.H.; validation, J.L. and H.L.; formal analysis, J.L.; date curation, P.H.; resources, J.L.; visualization, S.L. All authors have reviewed and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Li, S., He, P. et al. A multi objective collaborative reinforcement learning algorithm for flexible job shop scheduling. Sci Rep 15, 22838 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03681-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03681-6