Abstract

The ‘fairy circles’ of Mali, Namibia, and Australia, intriguing geomorphological features, have gained a lot of attention since some of them have been reported as sources of natural hydrogen. Although there have been many theories on the origin of these mysterious circular depressions in specific geological terrains, they are often explained as the escaping of free gas generated through the serpentinization of rocks at deeper depths. These circles are visible in the satellite images, which can be accessed on platforms like Google Maps and Bing Maps, making them potential sources of image data. Major research in this area has been carried out primarily in Mali, Namibia, Australia, etc.; however, considering the vegetation patterns, they may also be present in different parts of the world. This study combined computational modelling and geomorphological image data to develop pre-trained CNN-based predictive models that can detect the likelihood of fairy circles from satellite images. Through rigorous training, the study reports a set of such models that can detect the presence of fairy circles with an accuracy of 98%. Using these models, satellite images can be easily screened to detect and locate such patterns across the globe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

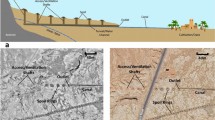

We are surrounded by many geomorphological mysteries for which proven theories have yet to be reported. ‘Fairy Circles’ (FC) are one of such geomorphological mysteries and have gained much attention worldwide. They are identified as circular areas of uncovered soil or sand gaps of almost similar sizes in the range of ~ 4–10 m in diameter1. They are, in general, uniformly spread across tens of square kilometers of areas in a way that there are no trees, bushes, or grasses, which typically cover the area between these circles2. The origin of these FCs has been a controversial topic for a long time; however, no concrete theory has been set up. Other ring-like structures have been identified during archeological surveys at several sites2,3, but FCs are one of their kind, making them quite mysterious. As such, some of the prime concepts which connect to their formation are insects (like ants/termites), self-arrangement of vegetation, gas theory, and the allelopathy of Euphorbia species4. So far, the presence of FCs has been reported only in the drylands of Namibia and Australia; however, their vegetation has distinguishable differences. Namibian FCs appear in sandy soil with space in surrounding vegetation, depicting significant soil moisture5, whereas FCs in Australia appear in fine soil textures with higher penetration of plant canopies6. Besides, in Namibian FCs, ants and termites have been reported to be the core drivers in their formation7, whereas in Australian FCs, vegetation water feedbacks were reported to be the main reasons for formation8. However, a recent report deciphers the traditional knowledge in Aboriginal Australian art and stories and soil excavation findings to reveal that these bare circles in the grasslands are nests occupied by harvester termites called Drepanotermes, which play a significant role in the synergy between soil, water, and grass9.

Many studies related to subsurface H2 gas concentration have been carried out in the last decade. Concentrations of H2 gas at around 1 m below the surface have been monitored in Russia10, the USA11, and Brazil12 on a time-resolved basis, but the actual source of this hydrogen is still debated. Interestingly, the shapes of these surfaces from where ydrogen (H2) leaks are also circular, making them often called fairy circles, which were extensively studied by Myagkiy et al. using 2-D transport modelling13. The effect of H2 emanations in soils, which results in small circular and elliptical depressions (fairy circles) and vegetation gaps, has been reported in Australia, the USA, Brazil, France, and Mali14,15,16. Recently, Guirado et al.17 revealed interesting findings on the existence of around 263 FC-like vegetation patterns from 15 countries and three continents, including Madagascar, the Sahel, and Middle-West Asia. The study focused on the global biogeography and the environmental drivers of FCs. The complex empirical observations of the large set of FCs in this study set new opportunities for progress in the theory of ecosystem spatial self-organization.

Advancements in the areas of Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), and Deep Learning (DL) in handling image data from satellite, multispectral, and hyperspectral cameras have made tremendous progress. Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) is a prominent research area in the field of remote sensing, and the classification of HSI using deep learning is currently a hot topic18,19,20. Classical semi-supervised models and DL have made remarkable progress in classifying image data in general and HSI data in particular21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30.

Convolution neural networks (CNN) have also been recently used to address diverse geographical aspects such as object-based image analysis for the classification of VHR imagery31,32, detecting land covers and change in trends using heterogeneous and homogenous images33,34,35. An early work on the detection and spatial analysis of FCs was carried out by Al-Sarayreh et al. using aerial images collected through Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) with various image segmentation techniques for Namibian and Australia36. The study led to extracting the geometric parameters like size and distance from these two sites and comparing them for their shapes. CNNs were employed to detect FCs in the two sites of Namibia37. Through data augmentation, around 9000 images were used to train two models based on the sliding window and selective search methods. The spatial and spectral characteristics of Namibia were also studied by Noy et al.38, where satellite images were processed and, using deep machine learning (CNN), the distributions of FCs were explored. The shape and size of each FC were characterized to retrieve the spatial patterns and then correlated with the geomorphological attributes of different locations. The study is a reference for unexplored landscapes, remote sensing, statistical analysis, and ML can facilitate spatial and spectral analyses. Few recent studies have also been carried out to study the spatiotemporal dynamics, extraction, and identification of vegetation in FCs39,40,41.

The current work hypothesizes that the structures of FCs are generally similar (circular or elliptical), irrespective of their place of origin. As such, the satellite images collected through services like Google and Bing Maps (https://www.bing.com/maps/) will provide relevant features to identify the unique patterns and can be used to train CNN-based models for identification and classification. In this regard, the main goal of the study is to use these satellite images to train different CNN models, which have been extensively used in image data, and report a methodology that can identify the presence of FCs from any satellite image. To be more specific, the aims of this study are: (a) to understand the features of FCs using CNN models, (b) to use edge detection algorithms with CNN models for accurate detection of FCs, and (c) to develop a robust methodology to detect FCs from satellite images.

Methodology

Data retrieval and processing

For the current study, we have used the coordinates of FCs and Non-FCs as reported by Guirado et al.17. The dataset contains the latitudes and longitudes of the upper left and lower right corners of the square bounding box for each site. The images of these sites were then collected from Bing Maps (https://www.bing.com/maps/) using an automated Python script. Further, each of these images was then cropped to a desired size to build the complete dataset. All the images were labeled data for distinguishing FCs and Non-FCs; hence, no separate labeling was performed.

Detection of fairy circles

Image detection and classification have achieved significant success with CNN for their ability to decipher patterns like edges, textures, colours, etc., with the help of the kernels. CNNs follow a hierarchical nature so that the initial layers extract simple features, whereas the deeper layers extract complex features from the input. Further, the pooling layers help reduce the spatial dimension of the feature maps, which provides translational invariance and reduces the computational cost. These convolution and pooling operations enable the models for end-to-end learning and eliminate the feature engineering in classical ML or DL tasks. Considering these aspects, four pre-trained CNN models – AlexNet42, VGG1644, InceptionV345, and ResNet-5046 were employed to detect the FCs from the satellite images. These models differ from one another based on their architecture and computational complexity.

AlexNet – This CNN model consists of 8 layers, of which five are convolution layers (some are pooling) and three are fully connected layers (the final layer is SoftMax). To reduce the overfitting in the fully connected layers, the ‘dropout’ regularization technique is used. AlexNet promoted the use of the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function, which accelerates the training by introducing non-linearity and addressing the vanishing gradient problem42.

VGG16 – This is a complex CNN model with 16 layers, consisting of 13 convolutional layers and three fully connected layers with tiny (3 × 3) convolution filters throughout the network. The network in VGG16 is split into sequential blocks, so each one contains a set of convolutional layers followed by a max pooling layer. A design of this kind allows effective feature extraction and dimensionality reduction. Like AlexNet, this model also uses ReLU activation function for non-linearity and SoftMax as the last fully connected layer43.

InceptionV3 – This model is made up of symmetric as well as asymmetric building blocks, which include convolutions, mean pooling, max pooling, concatenations, dropouts, and fully connected layers. It has a total of 48 layers across all these diverse blocks. What makes InceptionV3 different from others is the use of factorized convolutions, i.e., instead of using a large single layer, it applies smaller and efficient convolutions (a 3 × 3 convolution is factorized into a 1 × 3, which is followed by a 3 × 1 convolution) to reduce the computational cost44.

ResNet-50 – Residual Network (ResNet) comes in different depths, like ResNet-18, ResNet-34, ResNet-50, ResNet-101, and ResNet-152. In this study, we have used ResNet-50, which has 50 layers in the architecture. This model is based on the idea of using residual blocks, where the output of a layer is added to the input of that layer, also known as identity mapping, which is achieved by shortcut connections to skip one or more layers. The residual mapping is mathematically represented by,

where the function F represents residual mapping and x is the input to the residual block. This identity mapping allows gradients to flow more easily through the network during backpropagation, helps overcome the vanishing gradient problem, and enables the training of very deep networks45.

Edge detection methods

Edge detection algorithms identify the points in the image where the brightness varies sharply or has discontinuities. They are widely used in object detection tasks. Two edge detection algorithms – Roberts46 and Sobel47 were implemented in this work to identify the edges of the FCs and train them with the CNN models.

Roberts detector – It operates by computing the gradient approximation of an image using two 2 × 2 convolution kernels33. The metrics used in this detector are defined by,

The gradients Gx and Gy are then calculated by the 2D convolution operation of the Roberts operator and the image matrix I such that,

Finally, the magnitude of the gradient (G) and the direction (∆) is calculated by,

Sobel detector – Unlike the Roberts detector, Sobel uses metrics of size 3 × 3 (Sobel & Feldman, 1968) which are defined by,

Thereafter, the gradients in x and y (Gx and Gy) are calculated using Eq. 3 but with the Sobel operator followed by finding the magnitude as in Eq. 4 and direction (∆) by,

Evaluation metrics

To assess the performance of the models, various metrics were used, which included accuracy, binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss, Cohen Kappa score, area under the curve (ROC-AUC), precision, recall, and F1 score, as shown in Table 1. The detailed workflow of the current study is demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Detailed workflow for detecting FCs/Non-FCs from satellite images using CNN and CNN with edge detection algorithms as carried out in this study. The images were extracted from Bing Maps (https://www.bing.com/maps/) using an indigenous Python script in Python 3.8.18.

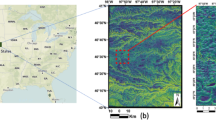

Interpretation with satellite data and synthetically generated data

For interpretation and validation of the models built in this study, we have retrieved the Sentinal-2 satellite images using Copernicus browser provided by European Space Agency (ESA)48 for two locations: (a) Newman, Australia (-23.356297, 119.865542) and (b) Namibia, Kunene Region (-19.214284, 13.608571) for the period January 2023 to April 2023. These locations have been reported to house a large number of FCs by Guirado et al.17 and many other studies. The exact locations of FCs with coordinates (-23.30760946, 119.795315) and (-18.98438714, 13.3232415) were then extracted with the Sentinel Application Platform (SNAP)49, a widely used software for all Sentinel Toolboxes. These extracted locations were resampled and fed to the RGB models in this study to evaluate their prediction capability.

Further, using the FC dataset in this study, we also built a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN)-based model50 to generate 150 synthetic FC images. As this model also generated noisy images, based on their structural similarity index, these images were segregated into five categories using an in-house Python script to concatenate them into five mosaic images. These five images were then subjected to RGB models and interpreted to understand how the models would perform on diverse geographic areas.

Results and discussion

Data collection and curation

The dataset used in the current study, from Guirado et al.17, consisted of coordinates of 15,032 sites in Namibia and Australia. Out of these, 7516 were for FC (labeled as 1) and 7516 for non-FC (labeled as 0), as can be interpreted from Fig. 2. An automated Python script was written for collecting the respective images (in RGB form) of these sites from Bing Maps using Selenium as a web driver. The program iterates through all the 15,032 coordinates one by one, saving FC and non-FC images in separate directories. All the images (7516 FC and 7516 non-FC) were collected at a zoom level of 18.4. These initial image data were of shape 1904 × 933 pixels with a dpi of 96. To avoid overloading the Bing Maps Server, the images were collected at a rate of 1 image per 10 s. Thereafter, these images were cropped to a square shape of 400 × 400 pixels, providing an estimated center point and side length of the square bounding box to a Python script. This script could calculate the upper left and lower right pixel coordinates and display the obtained bounding box in the image. The optimal center coordinates and the side length were obtained by adjusting these values and visualizing the bounding box, and ultimately, these regions were cropped out. Through this, the shapes of all the images maintained a homogeneity and would facilitate better training. While in most of the previous literatures it was reported that the FCs are circles of radius ≈ 4–10 m, here we have computed the structural similarity index of all these images which shows that the images were identical by 83.99% and remaining in the range of 50–60%, which were due to rich vegetation within which the FCs were present. The entire dataset was then split into train and validation sets as shown in Table 2. The complete training set and validation set are available in Zenodo51.

Samples of the image data used in training the CNN models in this study. The images (A–D) are FCs, whereas (E–H) are non-FCs collected from Bing Maps using the coordinates presented by Guirado et al.17. The images were extracted from Bing Maps (https://www.bing.com/maps/) using an indigenous Python script in Python 3.8.18.

Training the CNN models

This study used four CNN models – AlexNet, VGG16, InceptionV3, and ResNet-50. They were trained on the prepared dataset using the RGB images as input to classify FCs and Non-FCs with the assigned labels (1 and 0). A total of 100 epochs with a batch size of 32 with the Adam optimizer, a learning rate of 0.0001, and a binary cross-entropy loss function were set during the training process. Apart from these, the Robert and Sobel edge detector was also employed on the images, and then the model was retrained and evaluated. While using these methods, the three color channels (RGB) were reduced to a single channel (Grayscale), and the same was used for training and performance evaluation (Fig. S1). All these models were developed using Python and various deep learning packages.

Performance evaluation

The performance of all the models (with and without edge detectors) was measured using various metrics like accuracy, BCE loss, Cohen Kappa score, area under the curve (ROC-AUC), precision, recall, and F1. Considering all the metrics, it was seen that among all four models, InceptionV3 and VGG16 performed better than AlexNet and ResNet-50 (Table 3). The ROC-AUC plots for these models are in Fig. 3. The accuracy and loss with respect to epochs for each model are shown in Fig. S2.

While evaluating all the models with edge detectors, it was seen that both of them had similar results and, unlike the previous case, in this scenario, InceptionV3 and AlexNet performed better among all four models (Tables 4 and 5). The corresponding ROC-AUC plots for these models have been shown in Fig. 4.

During validation of the CNN models, the likelihood of image data to have FCs or the absence of FCs was computed. Figure 5 shows the probability of the presence and absence of FCs in the images from the InceptionV3 and VGG models, which gave comparatively better accuracy than the other two. Similarly, Figs. S3 to S6 represent the likelihood of the presence and absence of FCs using the CNN models with different edge detectors for the same set of images.

Probing into satellite data and synthetically generated data

The extracted satellite images of the Newman region, Australia, and the Kunene region, Namibia (Fig. 6) were subjected to all four RGB models, i.e., AlexNet, VGG16, InceptionV3, and ResNet-50, of this study. Among all these models, the location (-19.214284, 13.608571) was predicted to have a positive presence of FCs by AlexNet, VGG16, and ResNet-50, but was expected to have a negative presence by the Inception V3 model. Of the two extracted locations in (-23.356297, 119.865542), only one was predicted to have positive presence of FCs by the Inception V3 model, whereas the other was expected to have negative presence by all the models (Table 6). One of the possible regions might be that the Newman region in Australia had a lot of vegetation, whereas the Kunene region of Namibia had no vegetation or sparse vegetation. The data used in this study mainly consisted of FCs with sparse vegetation, which might have resulted in false negative predictions.

While probing into the presence of FCs in the mosaic images generated from synthetic data (Fig. 7), AlexNet predicted all five images as positive FCs with a mean accuracy of 0.99, whereas Inception V3 could predict three images as positive FCs with a 0.79 mean accuracy. ResNet-50 predicted two images as positive presence of FCs with a mean accuracy of 0.58, but VGG16 could not predict any positive instances out of the five images. This analysis shows that a consensus approach can be employed in new areas to detect the presence of FCs under similar geographical conditions.

Conclusion

The current study attempts to bridge the gap in solving geomorphological mysteries through computational modelling. Fairy circles have gained much attention in different scientific communities since they have been reported to be possible sources of natural H2. Although the reported fairy circles are mainly from Australia and Namibia, recent studies have evidence of their presence even in different parts of the world. As such, we have employed four CNN models - AlexNet, VGG16, InceptionV3, and Resnet-50, and trained them with a labeled dataset of images of having fairy circles and without fairy circles. Further, two edge detection methods, the Roberts edge detector and the Sobel edge detector, have been implemented on this data to retrain the models. The results show that all these models can detect the presence of fairy circles with significant accuracies (93–98%); however, when compared, InceptionV3 and VGG16 could predict with higher accuracy (98%) than the other two CNN models. Similarly, when compared among the models using edge detectors, VGG16 achieved the highest accuracy of 98% with Roberts edge detector followed by InceptionV3 and AlexNet with 97%. In case of Sobel edge detector, all the three algorithms, i.e. VGG16, AlexNet and InceptionV3 could predict with an accuracy of 97%. This study shows that the use of advanced computational modelling, such as CNN, can significantly contribute to solving complex and mysterious geomorphological problems.

Likelihood of an image with FCs; (A) InceptionV3 and (C) VGG16. Similarly, the likelihood of an image with non-FCs; (B) InceptionV3 and (D) VGG16. All the images were extracted from Bing Maps (https://www.bing.com/maps/) using an indigenous Python script in Python 3.8.18.

Satellite images from Sentinel-2 of (A) Newman, Australia (-23.356297, 119.865542) and (B) Kunene Region, Namibia (-19.214284, 13.608571) acquired from Copernicus browser48. Extracted areas of fairy circles from Australia (A1 and A2) and Namibia (B1) using SNAP Software version 11. The extracted images were validated using the proposed models in this study.

Data availability

The coordinates of fairy circles and non-fairy circle sites were collected from Guirado et al. (2023). The details are mentioned in the manuscript. All data sets utilized in this study are publicly available. The training and testing data sets used in the study are archived on Zenodo (Mahanta & Tiwari, 2024, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12754239) licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0. All the Python codes are available at https://github.com/hridoy69/Fairy-Circles.

References

Getzin, S., Yizhaq, H. & Tschinkel, W. R. Definition of Fairy circles and how they differ from other common vegetation gaps and plant rings. J. Veg. Sci., 32(6), e13092 (2021).

Eppelbaum, L. V. Localization of ring structures in Earth’s environments. In 7th Conf. of Archaeological Prospecting 145–148 (2007).

Eppelbaum, L. V., Khabarova, O. & Birkenfeld, M. Advancing archaeo-geophysics through integrated informational-probabilistic techniques and remote sensing. J. Appl. Geophys. 227, 105437 (2024).

Meyer, J. M., Schutte, C. S., Galt, N., Hurter, J. W. & Meyer, N. L. The Fairy circles (circular barren patches) of the Namib Desert-What do we know about their cause 50 years after their first description? S.Afr. J. Bot. 140, 226–239 (2021).

Cramer, M. D. & Barger, N. N. Are Namibian Fairy circles the consequence of self-organizing Spatial vegetation patterning? PloS One 8(8), e70876 (2013).

Getzin, S. et al. Adopting a spatially explicit perspective to study the mysterious Fairy circles of Namibia. Ecography 38 (1), 1–11 (2015).

Jürgens, N. et al. Largest on Earth: discovery of a new type of Fairy circle in Angola supports a termite origin. Ecol. Entomol. 46 (4), 777–789 (2021).

Getzin, S. et al. Discovery of Fairy circles in Australia supports self-organization theory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113 (13), 3551–3556 (2016).

Walsh, F. et al. First peoples’ knowledge leads scientists to reveal ‘fairy circles’ and termite Linyji are linked in Australia. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7 (4), 610–622 (2023).

Larin, N. et al. Natural molecular hydrogen seepage associated with surficial, rounded depressions on the European craton in Russia. Nat. Resour. Res. 24, 369–383 (2015).

Zgonnik, V. et al. Evidences for natural hydrogen seepages associated with rounded subsident structures: the Carolina Bays (Northern Carolina, USA). Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2, 31 (2015).

Prinzhofer, A. et al. Natural hydrogen continuous emission from sedimentary basins: the example of a Brazilian H2-emitting structure. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 44 (12), 5676–5685 (2019).

Myagkiy, A., Moretti, I. & Brunet, F. Space and time distribution of subsurface H2 concentration in so-called Fairy circles: insight from a conceptual 2-D transport model. BSGF-Earth Sci. B. 191 (1), 13 (2020).

Moretti, I., Brouilly, E., Loiseau, K., Prinzhofer, A. & Deville, E. Hydrogen emanations in intracratonic areas: new guide lines for early exploration basin screening. Geoscience 11 (3), 145 (2021).

Wang, L., Jin, Z., Chen, X., Su, Y. & Huang, X. The origin and occurrence of natural hydrogen. Energies 16 (5), 2400 (2023).

Frery, E., Langhi, L., Maison, M. & Moretti, I. Natural hydrogen seeps identified in the North Perth basin, Western Australia. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 46 (61), 31158–31173 (2021).

Guirado, E. et al. The global biogeography and environmental drivers of Fairy circles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120 (40), e2304032120 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Deep learning for hyperspectral image classification: an overview. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 57 (9), 6690–6709 (2019).

Ma, X., Wang, H. & Wang, J. Semisupervised classification for hyperspectral image based on multi-decision labeling and deep feature learning. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 120, 99–107 (2016).

Stupariu, M. S., Cushman, S. A., Pleşoianu, A. I., Pătru-Stupariu, I. & Fürst, C. Machine learning in landscape ecological analysis: a review of recent approaches. Landsc. Ecol. 37 (5), 1227–1250 (2022).

Aptoula, E., Ozdemir, M. C. & Yanikoglu, B. Deep learning with attribute profiles for hyperspectral image classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 13 (12), 1970–1974 (2016).

Wambugu, N. et al. Hyperspectral image classification on insufficient-sample and feature learning using deep neural networks: A review. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 105, 102603 (2021).

Yang, X. et al. Hyperspectral image classification with deep learning models. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 56 (9), 5408–5423 (2018).

Paoletti, M. E., Haut, J. M., Plaza, J. & Plaza, A. Deep learning classifiers for hyperspectral imaging: A review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 158, 279–317 (2019).

Audebert, N., Le Saux, B. & Lefevre, S. Deep learning for classification of hyperspectral data: A comparative review. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 7 (2), 159–173 (2019).

Li, Z., Huang, H. & Pu, C. Deep manifold learning network for hyperspectral image classification. In IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium 2021–2024 (2020).

Nalepa, J., Myller, M., Tulczyjew, L. & Kawulok, M. Deep ensembles for hyperspectral image data classification and unmixing. Remote Sens. 13 (20), 4133 (2021).

O’Byrne, M., Ghosh, B., Pakrashi, V. & Schoefs, F. Texture analysis based detection and classification of structure features on ageing infrastructure elements. Concr. Res. Irel. 1–6 (2018).

Li, Y., Li, J. & Pan, J. S. Hyperspectral image recognition using SVM combined deep learning. J. Internet Technol. 20 (3), 851–859 (2019).

Diaconescu, P. & Neagoe, V. E. A Higly Configurable Deep Learning Architecture for Hyperspectral Image Classification. In IEEE 13th International Symposium on Applied Computational Intelligence and Informatics (SACI) 197–200 (2019).

Mboga, N. et al. Fully convolutional networks and geographic object-based image analysis for the classification of VHR imagery. Remote Sens. 11 (5), (2019).

Cao, Z., Li, X., Jiang, J. & Zhao, L. 3D convolutional Siamese network for few-shot hyperspectral classification. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 14, 1–20 (2020).

Peˇ sek, O., Segal-Rozenhaimer, M. & Karnieli, A. Using convolutional neural networks for cloud detection on VENµS images over multiple Land-Cover types. Remote Sens. 14 (20) (2022).

Wu, J. et al. A multiscale graph convolutional network for change detection in homogeneous and heterogeneous remote sensing images. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 105, 102615 (2021).

Briechle, S., Krzystek, P. & Vosselman, G. Silvi-Net – A dual-CNN approach for combined classification of tree species and standing dead trees from remote sensing data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 98, 102292 (2021).

Al-Sarayreh, M., Moayed, Z., Bollard-Breen, B., Ramond, J. B. & Klette, R. Detection and spatial analysis of fairy circles. In IEEE International Conference on Image and Vision Computing New Zealand (IVCNZ) 1–6 (2016).

Zhu, Y. et al. Detection of fairy circles in UAV images using deep learning. In 15th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance (AVSS) 1–6 (2018).

Noy, K. et al. Spatial and spectral analysis of Fairy circles in Namibia on a landscape scale using satellite image processing and machine learning analysis. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 121, 103377 (2023).

Getzin, S., Holch, S., Ottenbreit, J. M., Yizhaq, H. & Wiegand, K. Spatio-temporal dynamics of Fairy circles in Namibia are driven by rainfall and soil infiltrability. Landsc. Ecol. 39 (7), 122 (2024).

Ruotong, Z., Kai, T., Jianru, Y., Jiangtao, H. & Weiguo, Z. Extraction of salt-marsh vegetation Fairy circles from UAV images by the combination of SAM visual segmentation model and random forest machine learning algorithm. Oceanol. Acta. 46, 1–11 (2024).

Jiangtao, H., Kai, T., Weiguo, Z., Ruotong, Z. & Shuai, L. Identification of salt marsh vegetation Fairy circles using random forest method and spatial-spectral data of unmanned aerial vehicle lidar. Opto-Electron. Eng. 51 (3), 230188–230181 (2024).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM. 60 (6), 84–90 (2017).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. ArXiv 14091556 (2014).

Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J. & Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2818–2826. (2016).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 770–778. (2016).

Roberts, L. Machine Perception of 3-D Solids, Optical and Electro-optical Information Processing (MIT Press, 1965).

Sobel, I. & Feldman, G. A 3x3 isotropic gradient operator for image processing. A Talk. Stanf. Artif. Project 271–272 (1968).

European Space Agency (ESA). Copernicus Open Access Hub. https://scihub.copernicus.eu (Accessed 8 Feb 2025) (2025).

European Space Agency. (n.d.). Sentinel Application Platform (SNAP) (Version 11) http://step.esa.int

Goodfellow, I. et al. Generative adversarial nets. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2672–2680 (2014).

Mahanta, H. J. & Tiwari, V. M. Deep Learning Twined Spatial Analysis for Detection of Mysterious ‘Fairy circles’. Zenodo (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank CSIR North East Institute of Science and Technology for the infrastructure support for this study. DBT, Govt. of India, is thanked for the support in the form of the Centre of Excellence in Advanced Computation and Data Sciences (Ref. No: BT/PR40188/BTIS/137/27/2021). One of the authors (VMT) also thanks ANRF-DST for the JC Bose Fellowship. The manuscript has been submitted with the approval of the Director, CSIR-NEIST, Jorhat.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study conception was made by VMT. Methodology, tests design and analysis were made by HJM and VMT. The first draft of the manuscript was written by HJM under the supervision of VMT. Both the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahanta, H.J., Tiwari, V.M. Deep learning twined spatial analysis for detection of mysterious fairy circles. Sci Rep 15, 40668 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03691-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-03691-4